The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Antibiotics: Methods, Interpretation, Clinical Relevance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Definition and Methods

2.1. What is MIC?

2.2. MIC Determination Methods

- Dilution methods

- in agar

- in a liquid medium

- ○

- micromethod/ microdilution

- ○

- macromethod/ macrodilution

- Gradient methods

- strips impregnated with a predefined concentration gradient of antibiotic

2.2.1. Dilution Methods

Bacterial Inoculum

- broth microdilution method 5 × 105 CFU (colony forming units) /mL [6]

Reading of Results

- bacteriostatic antibiotics against Gram-positive bacteria (chloramphenicol, tetracycline, clindamycin, erythromycin, linezolid, tedizolid) and against Gram-negative organisms (tygecycline, eravacycline): disregard pinpoint growth at the bottom of the well

- trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for all bacteria: read the MIC at the lowest concentration that inhibits ≥80% of growth as compared to the growth control.

2.2.2. Gradient Method

3. Interpretation of MIC

4. The Importance of MIC Values in Clinical Practice

- -

- Susceptible (S), standard dosing regimen: there is a high likelihood of therapeutic success using a standard dosing regimen of the agent.

- -

- Susceptible (I), increased exposure: there is a high likelihood of therapeutic success because exposure to the agent is increased by adjusting the dosing regimen or by its concentration at the site of infection.

- -

- Resistant: there is a high likelihood of therapeutic failure even when there is increased exposure.

5. Limitations Related to the Use of MIC Values

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cantón, R.; Morosini, M.I. Emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance following exposure to antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 35, 977–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- EUCAST Definitive Document. Methods for the determination of susceptibility of bacteria to antimicrobial agents. Terminology. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 1998, 4, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Clinical Breakpoints—Bacteria (v 10.0). 2020. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_10.0_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 28th ed.; CLSI Supplement M100; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2018; ISBN1 978-1-68440-066-9. [Print]; ISBN2 978-1-68440-067-6. [Electronic]. [Google Scholar]

- Nagayama, A.; Yamaguchi, K.; Watanabe, K.; Tanaka, M.; Kobayashi, I.; Nagasaa, Z. Final Report from the Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, Japanese Society of Chemotherapy, on the agar dilution method (2007). J. Infect. Chemother. 2008, 14, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- International Standard. ISO 20776-1. Susceptibility Testing of Infectious Agents and Evaluation of Performance of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test Devices—Part 1: Broth Micro-Dilution Reference Method for Testing the In Vitro Activity of Antimicrobial AGENTS Against Rapidly Growing Aerobic Bacteria Involved in Infectious Diseases, 2nd ed.; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, J.M. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001, 48 (Suppl. SA), 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. EUCAST Definitive Document E.DEF 3.1, June 2000, Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of antibacterial agents by agar dilution. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2000, 6, 509–515. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand, I.; Hilpert, K.; Hancock, R.E.W. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of antibacterial agents by broth microdilution. EUCAST Discussion Document E. Def 2003, 5.1. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2003, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. EUCAST Disk Diffusion Method. Version 8.0. 2020. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Disk_test_documents/2020_manuals/Manual_v_8.0_EUCAST_Disk_Test_2020,pdf (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Routine and Extended Internal Quality Control for MIC Determination and Disk Diffusion as Recommended by EUCAST. Version 10.0. 2020. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/QC/v_10.0_EUCAST_QC_tables_routine_and_extended_QC.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. EUCAST Reading Guide for Broth Microdilution. Version 2.0. 2020. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Disk_test_documents/2020_manuals/Reading_guide_BMD_v_2.0_2020,pdf (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Elshikh, M.; Ahmed, S.; Funston, S.; Dunlop, P.; McGaw, M.; Marchant, R.; Banat, I.M. Resazurin-based 96-well plate microdilution method for the determination of minimum inhibitory concentration of biosurfactants. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 38, 1015–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Prasetyoputri, A.; Jarrad, A.M.; Cooper, M.A.; Blaskovich, M.A. The eagle effect and antibiotic-induced persistence: Two sides of the same coin? Trends Microbiol. 2019, 27, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, G.A.; Beaulieu, B.; Arhin, F.F.; Belley, A.; Sarmiento, I.; Parr, T., Jr.; Moeck, G. Time–kill kinetics of oritavancin and comparator agents against Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009, 63, 1191–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jarrad, A.M.; Blaskovich, M.A.; Prasetyoputri, A.; Karoli, T.; Hansford, K.A.; Cooper, M.A. Detection and investigation of eagle effect resistance to vancomycin in clostridium difficile with an ATP-bioluminescence assay. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuschek, E.; Åhman, J.; Webster, C.; Kahlmeter, G. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of colistin–evaluation of seven commercial MIC products against standard broth microdilution for Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter spp. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, 865–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. EUCAST Warnings Concerning Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Products or Procedures. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Colistin—Problems Detected with Several Commercially Available Products. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Warnings/Warnings_docs/Warning_-_colistin_AST.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Poirel, L.; Jayol, A.; Nordmanna, P. Polymyxins: Antibacterial activity, susceptibility testing, and resistance mechanisms encoded by plasmids or chromosomes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 557–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Satlina, M.J. The search for a practical method for colistin susceptibility testing: Have we found it by going back to the future? J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019, 57, e01608-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karvanen, M.; Malmberg, C.; Lagerbäck, P.; Friberg, L.E.; Cars, O. Colistin is extensively lost during standard in vitro experimental conditions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00857-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. EUCAST Warnings Concerning Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Products or Procedures. Vancomycin Susceptibility Testing in Enterococcus Faecalis and E. faecium Using MIC Gradient Tests—A Modified Warning. 2019. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Warnings/Warnings_docs/Warning_-_glycopeptide_gradient_tests_in_Enterococci.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. EUCAST warnings Concerning Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Products or Procedures. Warning against the Use of Gradient Tests for Benzylpenicillin MIC in Streptococcus Pneumoniae. 2019. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Warnings/Warnings_docs/Warning_-_gradient_for_benzyl_and_pnc_21nov2019,pdf. (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Gwozdzinski, K.; Azarderakhsh, S.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Falgenhauer, L.; Chakraborty, T. An improved medium for colistin susceptibility testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56, e01950-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Green, D.A.; Macesic, N.; Uhlemann, A.C.; Lopez, M.; Stump, S.; Whittier, S.; Schuetz, A.N.; Simner, P.J.; Humphries, R.M. Evaluation of calcium-enhanced media for colistin susceptibility testing by gradient agar diffusion and broth microdilution. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e01522-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottell, J.L.; Webber, M.A. Experiences in fosfomycin susceptibility testing and resistance mechanism determination in Escherichia coli from urinary tract infections in the UK. J. Med. Microbiol. 2019, 68, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flam, R.K.; Rhomberg, P.R.; Huynh, H.K.; Sader, H.S.; Ellis-Grosse, E.J. In Vitro Activity of ZTI-01 (Fosfomycin for Injection) against Contemporary Gram-Negative and Gram-Positive Isolates—A Comparison of Inter-Method Testing. IDweek New Orlean. 2016. Available online: https://www.jmilabs.com/data/posters/IDWeek16-Fosfomycin-1833.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2020). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aprile, A.; Scalia, G.; Stefani, S.; Mezzatesta, M.L. In vitro fosfomycin study on concordance of susceptibility testing methods against ESBL and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 23, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanowisko Zespołu Roboczego, ds. Oznaczania Lekowrażliwości Zgodnie z Zaleceniami EUCAST w Sprawie Najczęściej Zgłaszanych Pytań Dotyczących Stosowania Rekomendacji EUCAST Wersja 4. Narodowy Program Ochrony Anty Biotyków. 2020. Available online: https://korld.nil.gov.pl/pdf/strona_23-06-2020-Stanowisko_Zespolu_Roboczego.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- E-Test—Reading Guide. Available online: https://www.ilexmedical.com/files/ETEST_RG.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Fosfomycin MIC Test Strips Technical Sheet- Liofilchem. Available online: http://www.liofilchem.net/login.area.mic/tech-nical_sheets/MTS45.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Kahlmeter, G. Defining antibiotic resistance-towards international harmonization. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2014, 119, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahlmeter, G. The 2014 Garrod Lecture: EUCAST–are we heading towards international agreement? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 2427–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mouton, J.W.; Brown, D.F.J.; Apfalter, P.; Canton, R.; Giske, C.G.; Ivanov, M.; MacGowan, A.P.; Rodloff, A.; Soussy, C.J.; Steinbakk, M.; et al. The role of pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics in setting clinical MIC breakpoints: The EUCAST approach. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, E37–E45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. EUCAST SOP 10.0. MIC Distributions and the Setting of Epidemiological Cutoff (ECOFF) Values. 2017. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/EUCAST_SOPs/EUCAST_SOP_10.0_MIC_distributions_and_epidemiological_cut-off_value__ECOFF__setting_20171117,pdf (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. MIC and Zone Diameter Distributions and ECOFFs. EUCAST General Consultation on “Considerations in the Numerical Estimation of Epidemiological Cutoff (ECOFF) Values”. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Consultation/2018/ECOFF_procedure_2018_General_Consultation_20180531,pdf (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Jorda, A.; Zeitlinger, M. Preclinical Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Studies and Clinical Trials in the Drug Development Process of EMA Approved Antibacterial Agents: A Review. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2020, 59, 1071–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Clinical Breakpoints—Bacteria (v 9.0). 2019. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_9.0_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Clinical Breakpoints—Bacteria (v 11.0). 2021. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_11.0_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- Wantia, N.; Gatermann, S.G.; Rothe, K.; Laufenberg, R. New EUCAST defnitions of S, I and R from 2019—German physicians are largely not aware of the changes. Infection 2020, 48, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, J.H.; Turnidge, J.D. Susceptibility test methods. In Manual of Clinical Microbiology, 11th ed.; American Society of Microbiology: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 1253–1273. [Google Scholar]

- Ezadi, F.; Ardebili, A.; Mirnejad, R. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing for polymyxins: Challenges, issues, and recommendations. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Humphries, R.M.; Abbott, A.N. Antibiotic susceptibility testing. In Clinical Microbiology E-Book, 1st ed.; American Society of Microbiology: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. e-104–135. [Google Scholar]

- Matono, T.; Morita, M.; Yahara, K.; Lee, K.I.; Izumiya, H.; Kaku, M. Emergence of resistance mutations in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi against fluoroquinolones. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2017, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Hal, S.J.; Lodise, T.P.; Paterson, D.L. The clinical significance of vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration in Staphylococcus aureus infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 755–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuti, J.L. Optimizing antimicrobial pharmacodynamics: A guide for your stewardship program. Rev. Médica Clínica Las Condes 2016, 27, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doron, S.; Davidson, L.E. Antimicrobial stewardship. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2011, 86, 1113–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morency-Potvin, P.; Schwartz, D.N.; Weinstein, R.A. Antimicrobial stewardship: How the microbiology laboratory can right the ship. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 381–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mölstad, S.; Löfmark, S.; Carlin, K.; Erntell, M.; Aspevall, O.; Blad, L.; Hanberger, H.; Hedin, K.; Hellman, J.; Norman, C.; et al. Lessons learnt during 20 years of the Swedish strategic programme against antibiotic resistance. Bull. World Health Organ. 2017, 95, 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Band, V.I.; Weiss, D.S. Heteroresistance: A cause of unexplained antibiotic treatment failure? PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsuji, B.T.; Pogue, J.M.; Zavascki, A.P.; Paul, M.; Daikos, G.L.; Forrest, A.; Giacobbe, D.R.; Claudio Viscoli, C.; Giamarellou, H.; Karaiskos, I.; et al. International Consensus Guidelines for the Optimal Use of the Polymyxins: Endorsed by the American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP), European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID), Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), International Society for Anti-infective Pharmacology (ISAP), Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), and Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists (SIDP). Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2019, 39, 10–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, L.; Gooderham, W.J.; Bains, M.; McPhee, J.B.; Wiegand, I.; Hancock, R.E. Adaptive resistance to the “last hope” antibiotics polymyxin B and colistin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is mediated by the novel two-component regulatory system ParR-ParS. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 3372–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, J.; Xie, S.; Ahmed, S.; Wang, F.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chai, X.; Wu, Y.; Cai, J.; Cheng, G. Antimicrobial activity and resistance: Influencing factors. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fritzenwanker, M.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Herold, S.; Wagenlehner, F.M.; Zimmer, K.P.; Chakraborty, T. Treatment options for carbapenem-resistant gram-negative infections. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt Int. 2018, 115, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumbarello, M.; Viale, P.; Viscoli, C.; Trecarichi, E.M.; Tumietto, F.; Marchese, A.; Spanu, T.; Ambretti, S.; Ginocchio, F.; Cristini, F.; et al. Predictors of mortality in bloodstream infections caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase–producing K. pneumoniae: Importance of combination therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 55, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chai, M.G.; Cotta, M.O.; Abdul-Aziz, M.H.; Roberts, J.A. What Are the Current Approaches to Optimising Antimicrobial Dosing in the Intensive Care Unit? Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, K.P.; Kuti, J.L.; Nicolau, D.P. Optimizing Antibiotic Pharmacodynamics for Clinical Practice. Pharm. Anal Acta 2013, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohr, J.F.; Wanger, A.; Rex, J.H. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling can help guide targeted antimicrobial therapy for nosocomial gram-negative infections in critically ill patients. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2004, 48, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onufrak, N.J.; Forrest, A.; Gonzalez, D. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic principles of anti-infective dosing. Clin. Ther. 2016, 38, 1930–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Roberts, J.A.; Lipman, J. Pharmacokinetic issues for antibiotics in the critically ill patient. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 37, 840–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shah, S.; Barton, G.; Fischer, A. Pharmacokinetic considerations and dosing strategies of antibiotics in the critically ill patient. J. Intensive Care Soc. 2015, 16, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Drusano, G.L. Prevention of resistance: A goal for dose selection for antimicrobial agents. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 36, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, A.J.; Sime, F.B.; Lipman, J.; Roberts, J.A. Individualising therapy to minimize bacterial multidrug resistance. Drugs 2018, 78, 621–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veiga, R.P.; Paiva, J.A. Pharmacokinetics–pharmacodynamics issues relevant for the clinical use of beta-lactam antibiotics in critically ill patients. Crit. Care 2018, 22, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Muller, A.E.; Huttner, B.; Huttner, A. Therapeutic drug monitoring of beta-lactams and other antibiotics in the intensive care unit: Which agents, which patients and which infections? Drugs 2018, 78, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinnollareddy, M.J.; Roberts, M.S.; Lipman, J.; Roberts, J.A. Beta-lactam pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in critically ill patients and strategies for dose optimization: A structured review. Clin. Exp. Pharm. Physiol. 2012, 39, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnidge, J.D. The pharmacodynamics of β-lactams. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998, 27, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masich, A.M.; Heavner, M.S.; Gonzales, J.P.; Claeys, K.C. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic considerations of beta-lactam antibiotics in adult critically ill patients. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2018, 20, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sime, F.B.; Roberts, M.S.; Peake, S.L.; Lipman, J.; Roberts, J.A. Does beta-lactam pharmacokinetic variability in critically ill patients justify therapeutic drug monitoring? A systematic review. Ann. Intensive Care 2012, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tam, V.H.; McKinnon, P.S.; Akins, R.L.; Rybak, M.J.; Drusano, G.L. Pharmacodynamics of cefepime in patients with Gram-negative infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2002, 50, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pea, F.; Viale, P.; Furlanut, M. Antimicrobial therapy in critically ill patients. A review of pathophysiological conditions responsible for altered disposition and pharmacokinetic variability. Clin. Pharm. 2005, 44, 1009–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsala, M.; Vourli, S.; Georgiou, P.C.; Pournaras, S.; Tsakris, A.; Daikos, G.L.; Mouton, J.W.; Meletiadis, J. Exploring colistin pharmacodynamics against Klebsiella pneumoniae: A need to revise current susceptibility breakpoints. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Aziz, M.H.; Roberts, J.A. PK/PD in Critical Illness. IDSAP Book 1; ACCP: Lenexa, KS, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, A.H.; Zhanel, G.G.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Noreddin, A.M. Monte Carlo simulation analysis of ceftobiprole, dalbavancin, daptomycin, tigecycline, linezolid and vancomycin pharmacodynamics against intensive care unit-isolated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2014, 41, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Roberts, J.A.; Alobaid, A.S.; Roger, C.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Lipman, J. Population pharmacokinetics of tigecycline in critically ill patients with severe infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00345-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parthasarathy, R.; Monette, C.E.; Bracero, S.S.; Saha, M. Methods for field measurement of antibiotic concentrations: Limitations and outlook. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2018, 94, fiy105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. EUCAST AST Directly from Blood Culture Bottles. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/rapid_ast_in_blood_cultures/ (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Hong, T.; Ndamukong, J.; Millett, W.; Kish, A.; Win, K.K.; Choi, Y.J. Direct application of E-test to Gram-positive cocci from blood cultures: Quick and reliable minimum inhibitory concentration data. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1996, 25, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontopidou, F.; Galani, I.; Panagea, T.; Antoniadou, A.; Souli, M.; Paramythiotou, E.; Koukos, G.; Karadani, I.; Armaganidis, A.; Giamarellou, H. Comparison of direct antimicrobial susceptibility testing methods for rapid analysis of bronchial secretion samples in ventilator-associated pneumonia. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2011, 38, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bianco, G.; Iannaccone, M.; Boattini, M.; Cavallo, R.; Costa, C. Assessment of rapid direct E-test on positive blood culture for same-day antimicrobial susceptibility. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2019, 50, 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Rationale Documents from EUCAST. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/publications_and_documents/rd/ (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Mouton, J.W.; Muller, A.E.; Canton, R.; Giske, C.G.; Kahlmeter, G.; Turnidge, J. MIC-based dose adjustment: Facts and fables. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 564–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Puttaswamy, S.; Gupta, S.K.; Regunath, H.; Smith, L.P.; Sengupta, S. A Comprehensive Review of the Present and Future Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing (AST) Systems. Arch Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doern, G.V.; Brecher, S.M. The Clinical Predictive Value (or Lack Thereof) of the Results of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, S11–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Falagas, M.E.; Tansarli, G.S.; Rafailidis, P.I.; Kapaskelis, A.; Vardakas, K.Z. Impact of antibiotic MIC on infection outcome in patients with susceptible Gram-negative bacteria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 4214–4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kullar, R.; Davis, S.L.; Levine, D.P.; Rybak, M.J. Impact of vancomycin exposure on outcomes in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: Support for consensus guidelines suggested targets. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moise-Broder, P.A.; Sakoulas, G.; Elipopoulos, G.M.; Schentag, J.J.; Forrest, A.; Moellering, R.C., Jr. Accessory gene regulator group II polymorphism in methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus is predictive of failure of vancomycin therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 38, 1700–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sakoulas, G.; Moise-Broder, P.A.; Schentag, J.J.; Forrest, A.; Moellering, R.C., Jr.; Elipopoulos, G.M. Relationship of MIC and bactericidal activity to efficacy of vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 2398–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maclayton, D.O.; Suda, K.J.; Coval, K.A.; York, C.B.; Garey, K.W. Case-control study of the relationship between MRSA bacteremia with a vancomycin MIC of 2 microg/mL and risk factors, costs, and outcomes in inpatients undergoing hemodialysis. Clin. Ther. 2006, 28, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bacterial Strains | Determination of MIC | Control Strains | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broth Dilution | Agar Dilution | |||||

| Mueller-Hinton Broth (MHB) | MHB + Defibrinated Horse Blood and β-NAD (MH-F) | Additional Supplementation | MHA | Additional Supplementation | ||

| Enterobacterales | all antibiotics except fosfomycin and mecillinam | - | - | fosfomycin | MHA + 25 mg/L glucose-6-phosphate | E. coli ATCC 25922, inhibitors only: ATCC E.coli 35218 or K. pneumoniae 700603 |

| Enterobacterales | all antibiotics except fosfomycin and mecillinam | - | - | mecillinam | - | E. coli ATCC 25922, inhibitors only: ATCC E.coli 35218 or K. pneumoniae 700603 |

| Pseudomonas spp. | all antibiotics except fosfomycin | - | - | fosfomycin | MHA + 25 mg/L glucose-6-phosphate | P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | co-trimoxazole | - | - | - | - | E. coli ATCC 25922 |

| Acinetobacter spp. | all antibiotics | - | - | - | - | P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 |

| Staphylococcus spp. | all antibiotics except fosfomycin | - | MHB + 2% NaCl for oxacillin, methicillin, nafcillin | fosfomycin | MHA + 25 mg/L glucose-6-phosphate | S. aureus ATCC 29213 |

| Staphylococcus spp. | all antibiotics except fosfomycin | - | MHB + 50 mg/L Ca++ for daptomycin | - | - | S. aureus ATCC 29213 |

| Staphylococcus spp. | all antibiotics except fosfomycin | - | MHB + 0.002% polysorbate 80 for dalbavancin, oritavancin, televancin | - | - | S. aureus ATCC 29213 |

| Enterococcus spp. | all antibiotics | - | - | - | - | E. faecalis ATCC 29212 |

| Streptococcus A,B, C,G gr. | - | all antibiotics | MH-F broth + 0.002% polysorbate 80 for dalbavancin, oritavancin, televanci | - | - | S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | - | all antibiotics | - | - | - | S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 |

| Streptococcus gr. viridans | - | all antibiotics | MH-F broth + 0.002% polysorbate 80 for dalbavancin, oritavancin, televanci | - | - | S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | - | all antibiotics | - | - | - | H. influenzae ATCC 49766 |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | - | all antibiotics | - | - | - | H. influenzae ATCC 49766 |

| Listeria monocytog enes | - | all antibiotics | - | - | - | S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 |

| Pasteurella multocida | - | all antibiotics | - | - | - | H. influenzae ATCC 49766 |

| Corynebacterium spp. | - | all antibiotics | - | - | - | S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 |

| Kingella kingae | - | all antibiotics | - | - | - | H. influenzae ATCC 49766 |

| Aeromonas sanguinicola and urinae | - | all antibiotics | - | - | - | P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 |

| Antibiotics | Solvent | Diluent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| penicillins | penicillin, methicillin, nafcillin, oxacillin, azlocillin, mecillinam, mezlocillin, carbenicillin, piperacillin | water | |

| amoxicillin, ticarcillin | phosphate buffer pH 6.0, 0.1 mol/L | ||

| ampicillin | phosphate buffer pH 8.0, 0.1 mol/L | phosphate buffer pH 8.0, 0.1 mol/L | |

| beta-lactam inhibitors of beta-lactamases | sulbactam, tazobactam, | water | |

| clavulanic acid, | phosphate buffer pH 6.0, 0.1 mol/L | ||

| non beta-lactam inhibitors of beta-lactamases | avibactam, relebactam | water | |

| cephalosporins | cefaclor, cefamandole, cefonicid, cefoperazone, cefotaxime, cefoxitin, ceftozoxime, ceftoplozane, ceftriaxone | water | |

| cefazolin, cefepime, cefuroxime | phosphate buffer pH 6.0, 0.1 mol/L | ||

| ceftazidime | sodium carbonate | Water | |

| ceftaroline | DMSO | Saline | |

| cephalexin, cephalotin, cephradine | phosphate buffer pH 8.0, 0.1 mol/L | water | |

| carbapenems | faropenem, meropenem | water | |

| ertapenem | phosphate buffer pH 6.0, 0.1 mol/L | ||

| imipenem, ertapenem | phosphate buffer pH 7.2, 0.01 mol/L | ||

| meropenem-varborbactam | DMSO | water | |

| aminoglycosides | amikacin, gentamicin, kanamycin, netilmicin, streptomycin, plazomicin, tobramycin | water | |

| lincosamides | clindamycin | water | |

| macrolides | azitromycin | 95% etanol | broth medium |

| clarythromycin | methanol | phosphate buffer pH 6.5, 0.1 mol/L | |

| erythromycin | 95% etanol | water | |

| quinolones | cinafloxacin, finafloxacin, garenoxacin, gatifloxacin, gemifloxacin, moxifloxacin, sparfloxacin, ofloxacin *, levofloxacin *, norfloxacin * | water | |

| tetracyclines | tetracycline, minocycline, doxycycline, tigecycline, eravacycline | water | |

| polymyxins | colistin, polymyxin B | water | |

| glycopeptides | teicoplanin, vancomycin | water | |

| telavancin | DMSO | ||

| lipoglycopeptides | dalbavancin | DMSO | |

| cyclic lipopeptide | daptomycin | water | |

| oxazolidinones | linezolid | water | |

| tedizolid | DMSO | ||

| other antibiotics | fosfomycin, fusidic acid, mupirocin, quinupristin-dalfopristin, | water | |

| fidaxomicin, metronidazole | DMSO | water | |

| chloramphenicol | 95% ethanol | water | |

| rifampicin | methanol | water | |

| Antibiotic(s) | Group of Bacteria |

|---|---|

| fosfomycin | Enterobacterales except E. coli, Staphylococcus spp. |

| tigecycline | Enterobacterales except E. coli, Citrobacter koserii |

| colistin | all Gram-negative rods |

| all antibiotics | Neisseria spp., anaerobes |

| beta-lactams | penicillin nonsusceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae |

| glycopeptides/ lipoglycopeptides | Staphylococcus spp. |

| dalbavancin, oritavancin | Streptococcus group: Viridans, A,B,C,G |

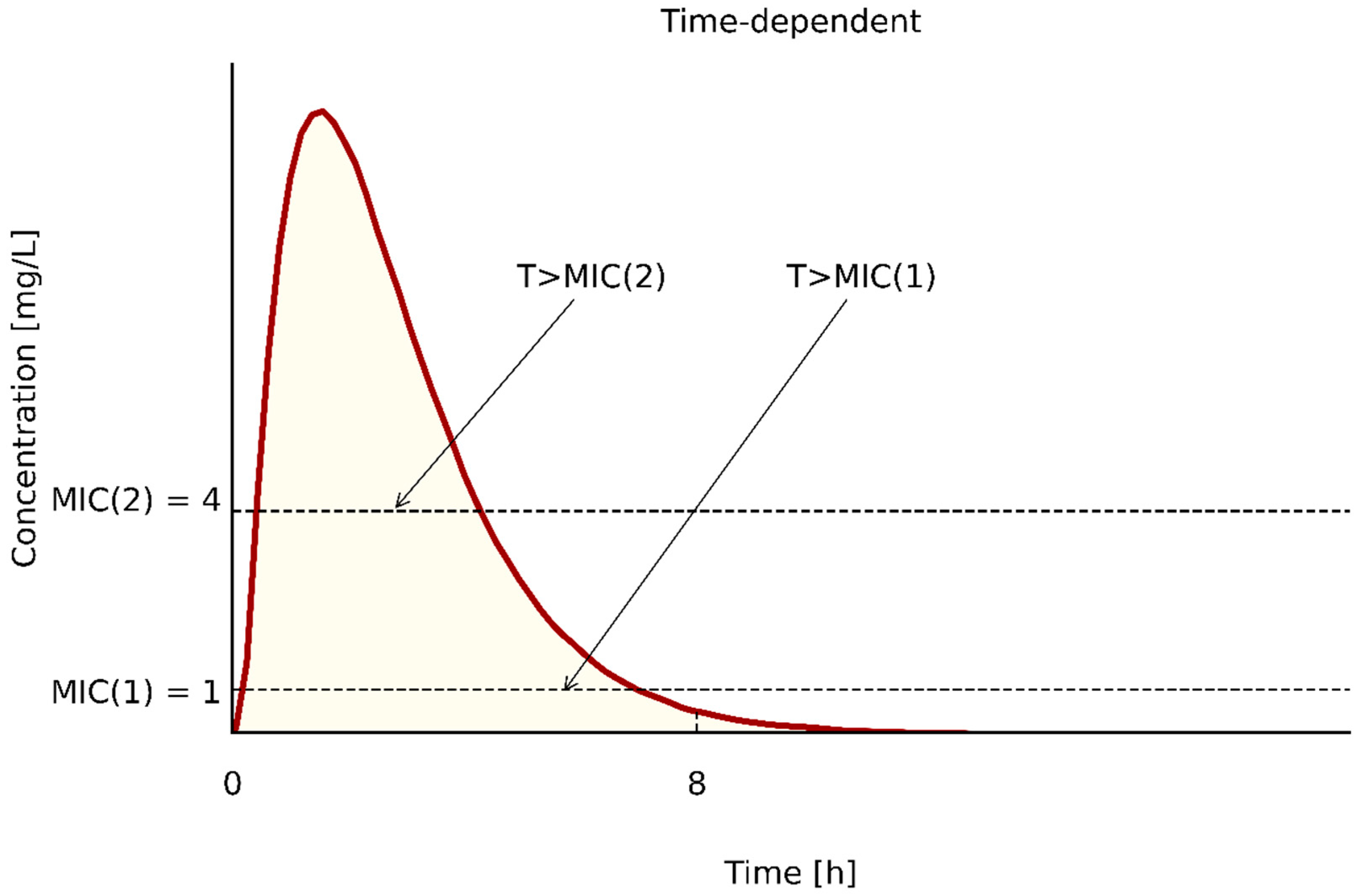

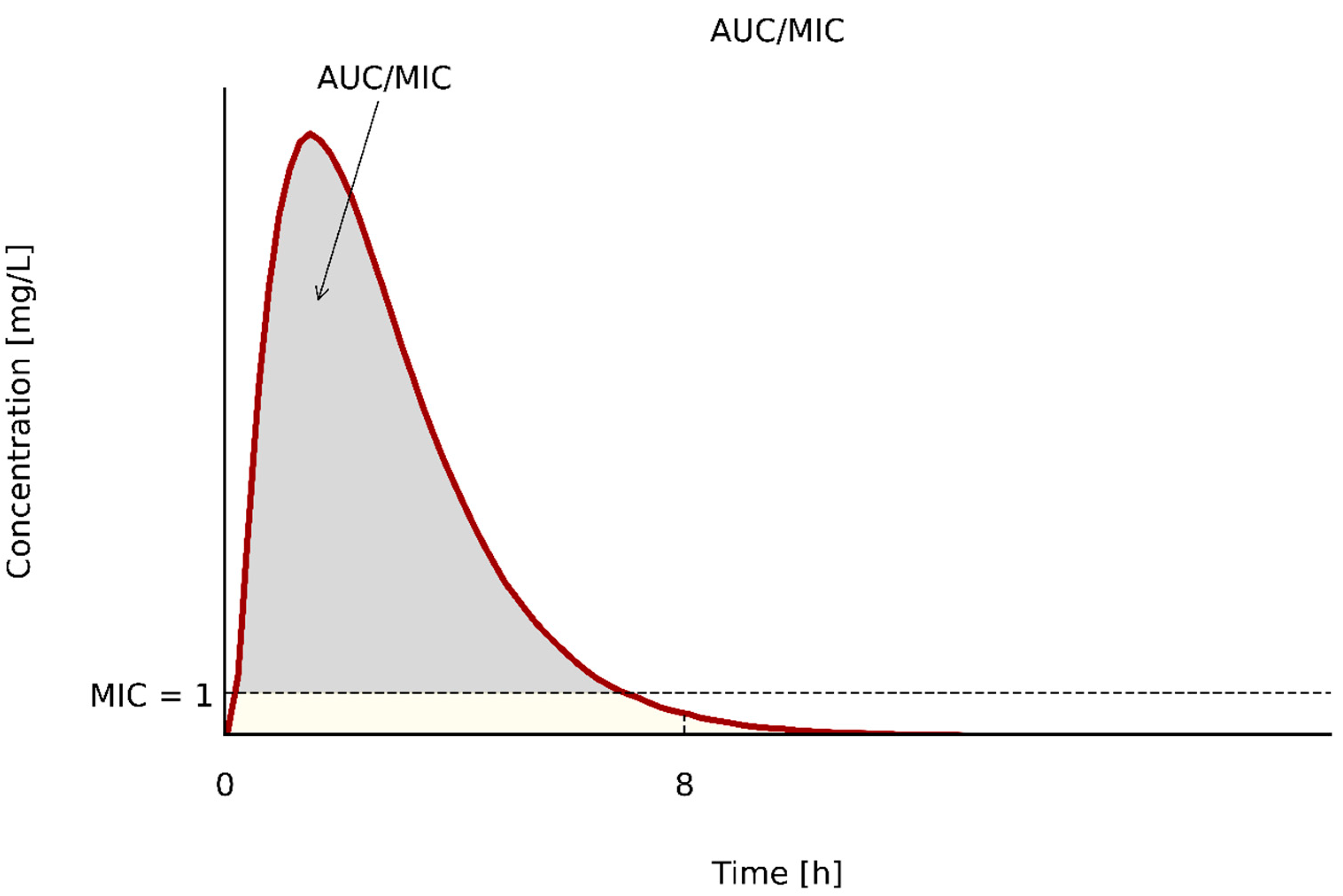

| PK/PD Type | Antibiotics | PK/PD Index | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| T > MIC | penicillins | ≥50 | [58,60,64,69] |

| cephalosporins | ≥50–70 | [58,60,64,69] | |

| carbapenems | ≥40 | [58,60,64,69] | |

| for patients with immunosupresion | 100 | [60,65,66] | |

| Cmax/MIC | aminoglycosides | >8 | [58,64] |

| fluoroquinolones | >8 | [58,64] | |

| polymyxins | ∫Cmax/MIC ≥ 6 | [73] | |

| metronidazole | NK | ||

| AUC/MIC | aminoglycosides | >70 [47]; ≥156 [41] | [58,64] |

| ciprofloxacin | AUC/MIC > 125; ∫AUC/MIC > 88 | [60] | |

| levofloxacin | AUC/MIC > 34; ∫AUC/MIC > 24 | [60] | |

| vancomycin | AUC/MIC > 400; ∫AUC/MIC > 200 | [60] | |

| daptomycin | AUC/MIC 388–537 [47]; AUC/MIC ≥ 666 [57] | [64,74] | |

| oksazolidinones | >80 | [58,64,74] | |

| polymyxins | total AUC/MIC > 50; ∫AUC/MIC > 25 | [64,73] | |

| fosfomycin | >8.6 | [64] | |

| tygecycline | skin and skin structure infections AUC/MIC ≥ 17.9 | [76] | |

| Intra-abdominal infections AUC/MIC ≥ 6.96 | [76] | ||

| hospital acquired pneumonia AUC/MIC ≥4.5 | [76] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kowalska-Krochmal, B.; Dudek-Wicher, R. The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Antibiotics: Methods, Interpretation, Clinical Relevance. Pathogens 2021, 10, 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10020165

Kowalska-Krochmal B, Dudek-Wicher R. The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Antibiotics: Methods, Interpretation, Clinical Relevance. Pathogens. 2021; 10(2):165. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10020165

Chicago/Turabian StyleKowalska-Krochmal, Beata, and Ruth Dudek-Wicher. 2021. "The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Antibiotics: Methods, Interpretation, Clinical Relevance" Pathogens 10, no. 2: 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10020165

APA StyleKowalska-Krochmal, B., & Dudek-Wicher, R. (2021). The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Antibiotics: Methods, Interpretation, Clinical Relevance. Pathogens, 10(2), 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10020165