Aphrophoridae Role in Xylella fastidiosa subsp. pauca ST53 Invasion in Southern Italy

Abstract

:1. The Insect-Borne Plant Pathogen

2. Non-Vector/Vector Pest Damage

2.1. Non-Vector Pest Damage

2.2. Vector Pest Damage

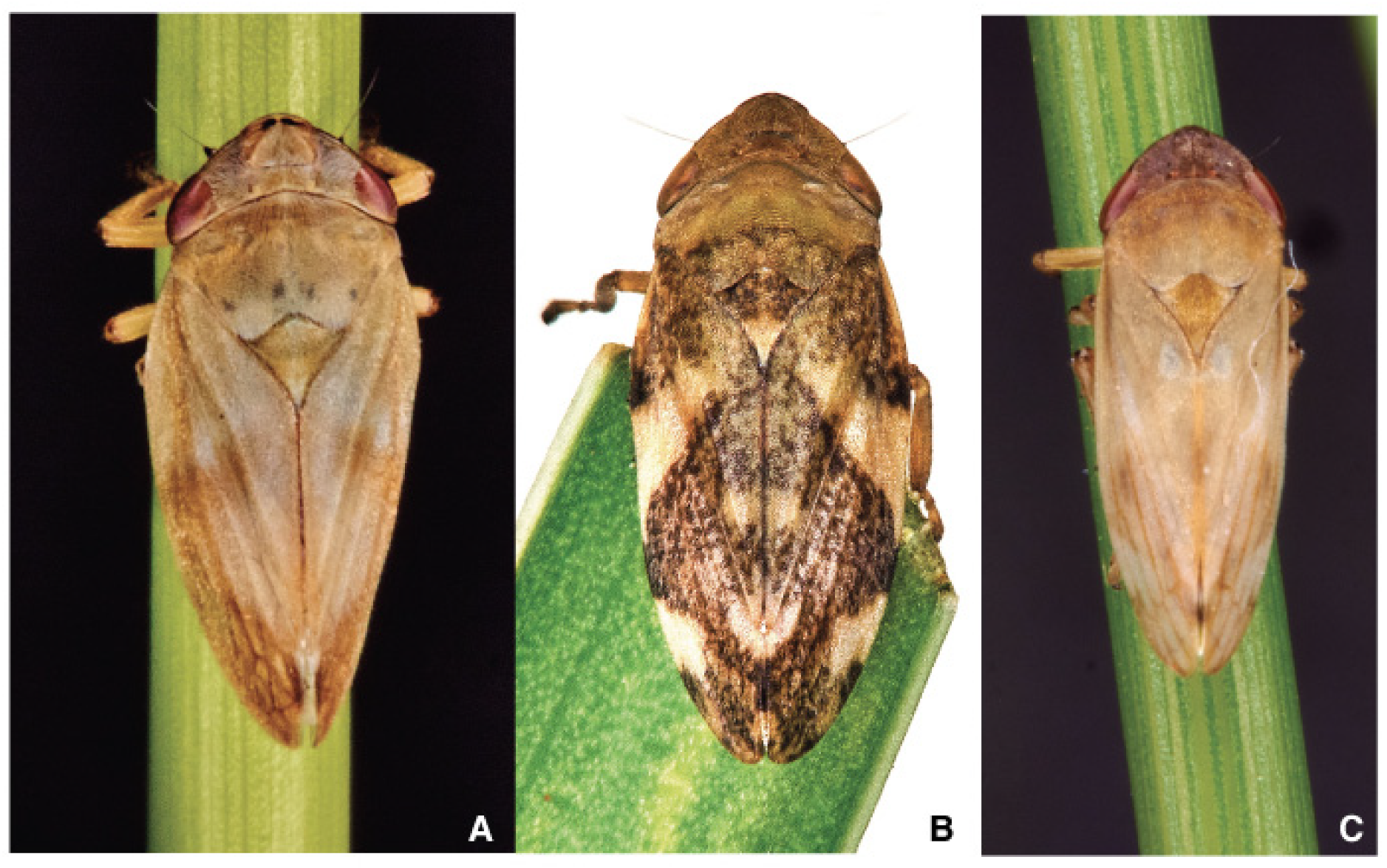

2.2.1. Vector Species Identification

2.2.2. Morphology and Identification

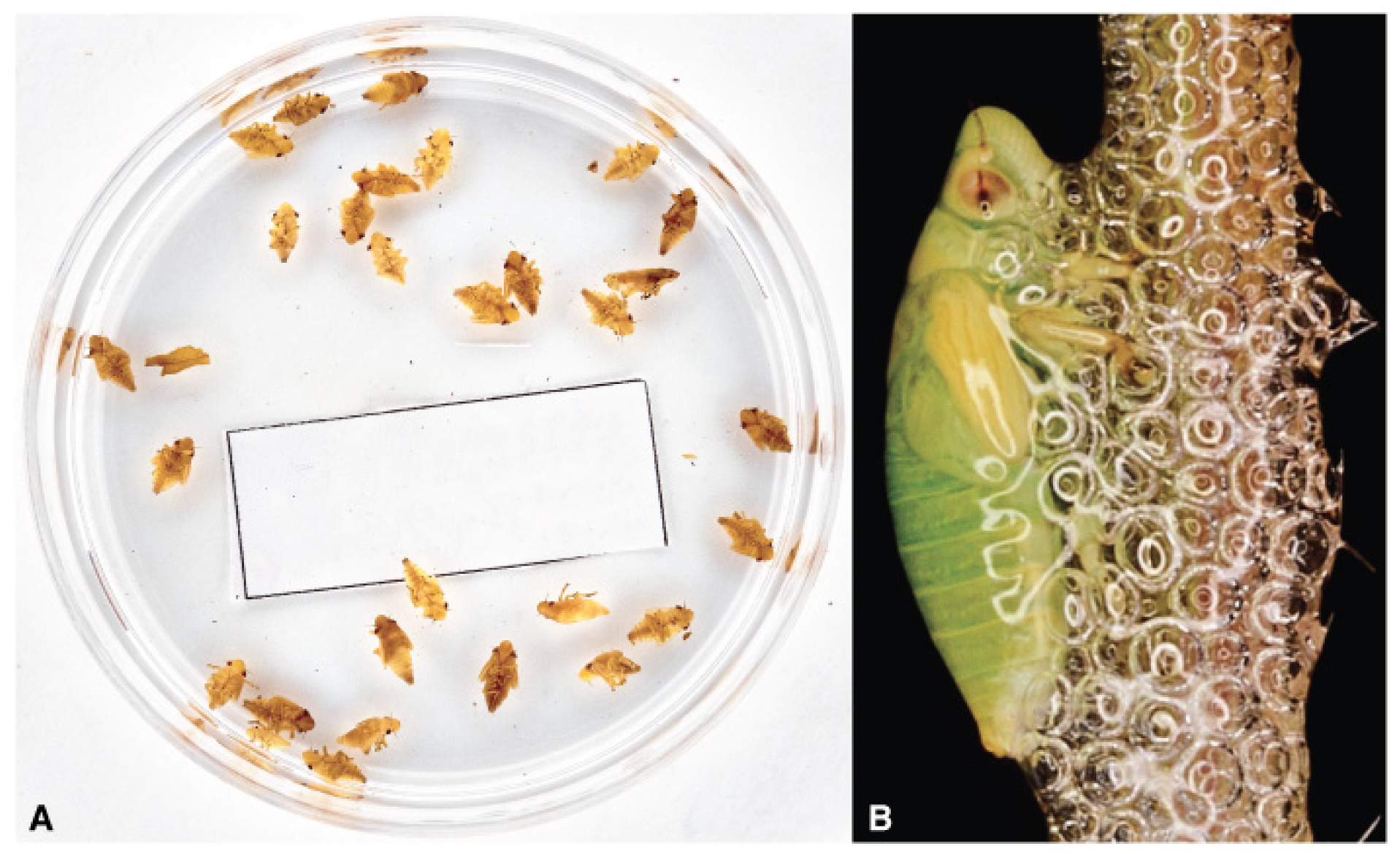

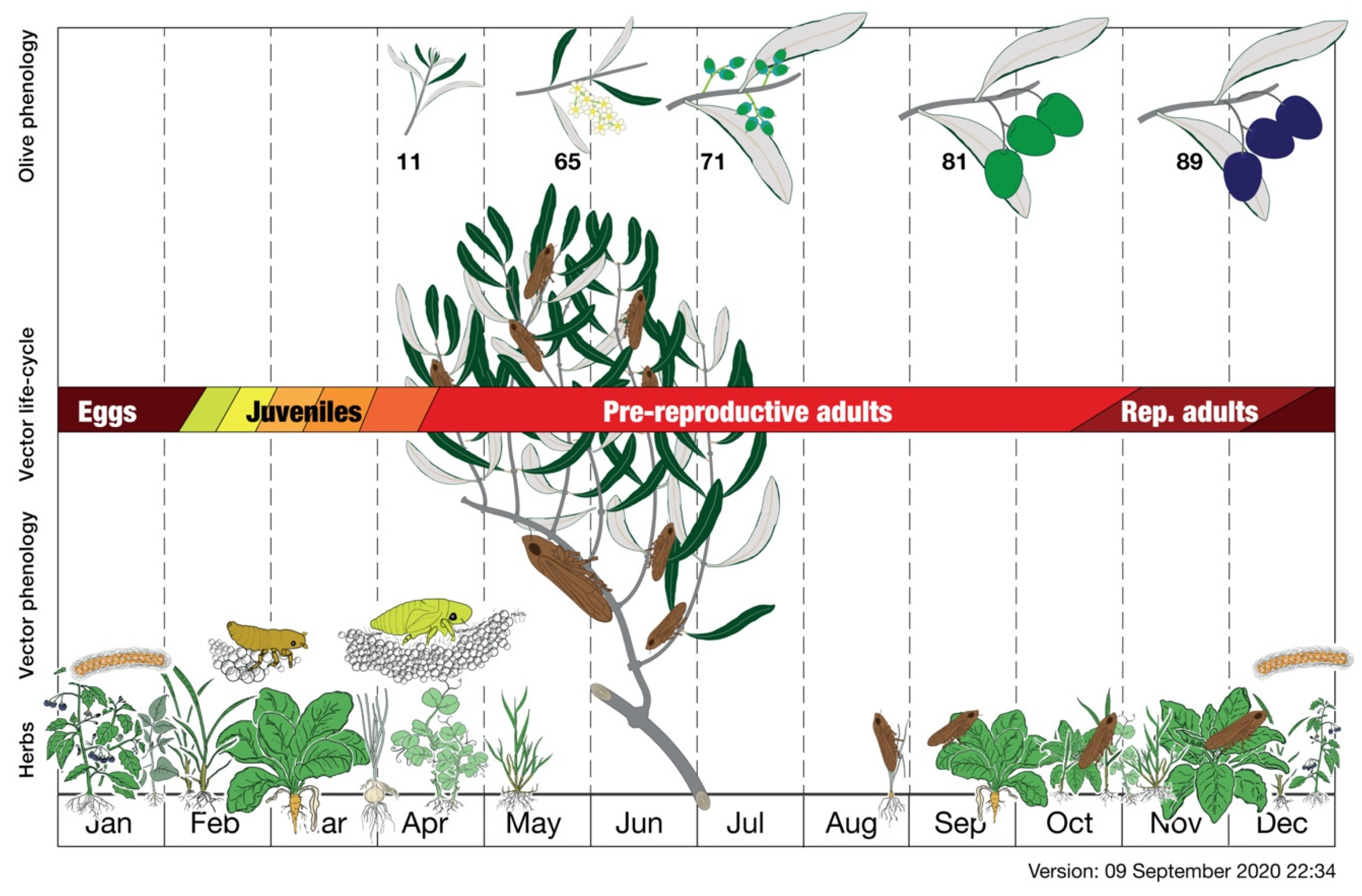

3. Vector Bionomics

4. Damage

Damage by Xylella fastidiosa pauca ST53 Infection

5. Vector–Pathogen: Rationale Control

5.1. Control Strategy

5.2. Control Step Sequences

5.2.1. First Step: Details

5.2.2. Second Step: Details

5.2.3. Third Step: Details

- –

- Preventive, to impede all the future infections from the vector because the insect dies on the tree during Xfp53 acquisition;

- –

- Protective, to limit the vector action to one infection; vector dies on the just infected twig and impeding the infection of other olive trees or the repeated transmissions on the same plant.

5.2.4. Control Steps: More about

5.3. Quantitative Control Approach

5.4. Symptomatic Plants Uprooting

5.5. Vector Census

5.6. Actual Engagement

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wells, J.M.; Raju, B.C.; Hung, H.Y.; Weisburg, W.G.; Mandelco-Paul, L.; Brenner, D.J. Xylella fastidiosa gen. nov., sp. nov.: Gram-negative, xylem-limited, fastidious plant bacteria related to Xanthomonas spp. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1987, 37, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brlansky, R.H.; Timmer, L.W.; French, W.J.; McCoy, R.E. Colonization of the sharpshooter vector, Oncometopia nigricans and Homalodisca coagulata by xylem-limited bacteria. Phytopathology 1983, 73, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, B.L.; Purcell, A.H. Populations of Xylella fastidiosa in plants required for transmission by an efficient vector. Phytopathology 1997, 87, 1197–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Newman, K.L.; Almeida, R.P.; Purcell, A.H.; Lindow, S.E. Cell-cell signaling controls Xylella fastidiosa interactions with both insects and plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 1737–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lambais, M.R.; Goldman, M.H.; Camargo, L.E.; Goldman, G.H. A genomic approach to the understanding of Xylella fastidiosa pathogenicity. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2000, 3, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firrao, G.; Scortichini, M.; Pagliari, L. Orthology-Based Estimate of the Contribution of Horizontal Gene Transfer from Distantly Related Bacteria to the Intraspecific Diversity and Differentiation of Xylella fastidiosa. Pathogens 2021, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Update of the Xylella spp. host plant database. EFSA J. 2018, 16, e05408. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA. Update of the Xylella spp. host plant database–systematic literature search up to 30 June 2019. EFSA J. 2020, 18, e06114. [Google Scholar]

- Potnis, N.; Kandel, P.P.; Merfa, M.V.; Retchless, A.C.; Parker, J.K.; Stenger, D.C.; Almeida, R.P.P.; Bergsama-Vlami, M.; Westenberg, M.; Cobine, P.A.; et al. Patterns of inter-and intrasubspecific homologous recombination inform eco-evolutionary dynamics of Xylella fastidiosa. ISME J. 2019, 13, 2319–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.I.; Chacón-Díaz, C.; Rodríguez-Murillo, N.; Coletta-Filho, H.D.; Almeida, R.P. Impacts of local population history and ecology on the evolution of a globally dispersed pathogen. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, D.L. Physiological and pathological characteristics of virulent and avirulent strains of the bacterium that causes Pierce’s disease of grapevine. Phytopathology 1985, 75, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, G.E.; Stojanovic, B.J.; Kuklinski, R.F.; DiVittorio, T.J.; Sullivan, M.L. Scanning electron microscopy of Piercés disease bacterium in petiolar xylem of grape leaves. Phytopathology 1985, 75, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, K.L.; Almeida, R.P.; Purcell, A.H.; Lindow, S.E. Use of a green fluorescent strain for analysis of Xylella fastidiosa colonization of Vitis vinifera. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 7319–7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cardinale, M.; Luvisi, A.; Meyer, J.B.; Sabella, E.; De Bellis, L.; Cruz, A.C.; Ampatzidis, Y.; Cherubini, P. Specific fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) test to highlight colonization of xylem vessels by Xylella fastidiosa in naturally infected olive trees (Olea europaea L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Killiny, N.; Prado, S.S.; Almeida, R.P. Chitin utilization by the insect-transmitted bacterium Xylella fastidiosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 6134–6140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Almeida, R.P. Xylella fastidiosa vector transmission biology. In Vector-Mediated Transmission of Plant Pathogens; Brown, J.K., Ed.; American Phytopathological Society Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2016; pp. 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Nunney, L.; Ortiz, B.; Russell, S.A.; Sánchez, R.R.; Stouthamer, R. The complex biogeography of the plant pathogen Xylella fastidiosa: Genetic evidence of introductions and subspecific introgression in Central America. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schaad, N.W.; Postnikova, E.; Lacy, G.; Chang, C.J. Xylella fastidiosa subspecies: X. fastidiosa subsp. piercei, subsp. nov., X. fastidiosa subsp. multiplex subsp. nov., and X. fastidiosa subsp. pauca subsp. nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 27, 290–300, Correction in 2004, 27, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, A.H.; Saunders, S.R.; Hendson, M.; Grebus, M.E.; Henry, M.J. Causal role of Xylella fastidiosa in oleander leaf scorch disease. Phytopathology 1999, 89, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schuenzel, E.L.; Scally, M.; Stouthamer, R.; Nunney, L. A multigene phylogenetic study of clonal diversity and divergence in North American strains of the plant pathogen Xylella fastidiosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 3832–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guan, W.; Shao, J.; Zhao, T.; Huang, Q. Genome sequence of a Xylella fastidiosa strain causing mulberry leaf scorch disease in Maryland. Genome Announc. 2014, 2, e00916-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Denancé, N.; Briand, M.; Gaborieau, R.; Gaillard, S.; Jacques, M.A. Identification of genetic relationships and subspecies signatures in Xylella fastidiosa. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Su, C.C.; Deng, W.L.; Jan, F.J.; Chang, C.J.; Huang, H.; Shih, H.T.; Chen, J. Xylella taiwanensis sp. nov., causing pear leaf scorch disease. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 4766–4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loconsole, G.; Saponari, M.; Boscia, D.; D’Attoma, G.; Morelli, M.; Martelli, G.P.; Almeida, R.P.P. Intercepted isolates of Xylella fastidiosa in Europe reveal novel genetic diversity. Eur. J. Plant. Pathol. 2016, 146, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giampetruzzi, A.; Saponari, M.; Almeida, R.P.P.; Essakhi, S.; Boscia, D.; Loconsole, G.; Saldarelli, P. Complete Genome Sequence of the Olive-Infecting Strain Xylella fastidiosa subsp. pauca De Donno. Genome Announc. 2017, 5, e00569-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Digiaro, M.; Valentini, F. The presence of Xylella fastidiosa in Apulia region (Southern Italy) poses a serious threat to the whole Euro-Mediterranean region. Cent. Int. De Hautes Etudes Agron. Méditerranéennes Watch Lett. 2015, 33, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Giampetruzzi, A.; Loconsole, G.; Boscia, D.; Calzolari, A.; Chiumenti, M.; Martelli, G.P.; Saldarelli, P.; Almeida, R.P.P.; Saponari, M. Draft genome sequence of CO33, a coffee-infecting isolate of Xylella fastidiosa. Genome Announc. 2015, 3, e01472-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haelterman, R.M.; Tolocka, P.A.; Roca, M.E.; Guzmán, F.A.; Fernández, F.D.; Otero, M.L. First presumptive diagnosis of Xylella fastidiosa causing olive scorch in Argentina. J. Plant Pathol. 2015, 97, 393. [Google Scholar]

- Coletta-Filho, H.D.; Francisco, C.S.; Lopes, J.R.S.; De Oliveira, A.F.; de Oliveira Da Silva, L.F. First report of olive leaf scorch in Brazil, associated with Xylella fastidiosa subsp. pauca. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2016, 55, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Gomila, M.; Moralejo, E.; Busquets, A.; Segui, G.; Olmo, D.; Nieto, A.; Juan, A.; Lalucat, J. Draft genome resources of two strains of Xylella fastidiosa XYL1732/17 and XYL2055/17 isolated from Mallorca vineyards. Phytopathology 2019, 109, 222–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- EPPO. Available online: https://www.eppo.int/ACTIVITIES/plant_quarantine/A2_list (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Casagrande, R. Biological terrorism targeted at agriculture: The threat to US national security. Nonproliferation Rev. 2000, 7, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budowle, B.; Murch, R.; Chakraborty, R. Microbial forensics: The next forensic challenge. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2005, 119, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mark, J.A.; Green, L.D.; Deshpande, A.; White, P.S. System integration and development for biological warfare agent surveillance. Opt. Photonics Glob. Homel. Secur. 2007, 6540, 65401D. [Google Scholar]

- Nutter, F.W.; Madden, L.V. Plant Pathogens as Biological Weapons Against Agriculture. In Beyond Anthrax; Lutwick, L.I., Lutwick, S.M., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Russmann, H.; Richardt, A. Biological Warfare Agents. In Decontamination of Warfare Agents; Richardt, A., Blum, M.M., Eds.; Wiley-VCH Verl GmbH Co.: Weinheim, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J.M.; Allen, C.; Coutinho, T.; Denny, T.; Elphinstone, J.; Fegan, M.; Gillings, M.; Gottwald, T. Plant-pathogenic bacteria as biological weapons–real threats? Phytopathology 2008, 98, 1060–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saponari, M.; Boscia, D.; Nigro, F.; Martelli, G.P. Identification of DNA sequences related to Xylella fastidiosa in oleander, almond and olive trees exhibiting leaf scorch symptoms in Apulia. J. Plant Pathol. 2013, 95, 668. [Google Scholar]

- Janse, J.D. Phytobacteriology—Principles and Practice; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Janse, J.D.; Obradovic, A. Xylella fastidiosa: Its biology, diagnosis, control and risks. J. Plant Pathol. 2010, 92, S35–S48. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, R.P.; Nunney, L. How do plant diseases caused by Xylella fastidiosa emerge? Plant Dis. 2015, 99, 1457–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bodino, N.; Cavalieri, V.; Dongiovanni, C.; Simonetto, A.; Saladini, M.A.; Plazio, E.; Gilioli, G.; Molinatto, G.; Saponari, M.; Bosco, D. Dispersal of Philaenus spumarius (Hemiptera: Aphrophoridae), a Vector of Xylella fastidiosa, in Olive Grove and Meadow Agroecosystems. Environ. Entomol. 2021, 50, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, A.H.; Finlay, A.H.; McLean, D.L. Pierce’s disease bacterium: Mechanism of transmission by leafhopper vectors. Science 1979, 206, 839–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killiny, N.; Almeida, R.P. Xylella fastidiosa afimbrial adhesins mediate cell transmission to plants by leafhopper vectors. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeger, M.; Bragard, C. The epidemiology of Xylella fastidiosa; A perspective on current knowledge and framework to investigate plant host–vector–pathogen interactions. Phytopathology 2019, 109, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO. Handbook for Integrated Vector Management; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick, A.M.; Randolph, S.E. Drivers, dynamics, and control of emerging vector-borne zoonotic diseases. Lancet 2012, 380, 1946–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, L.; Medlock, J.; Murray, V. Impact of drought on vector-borne diseases–how does one manage the risk? Public Health 2014, 128, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eigenbrode, S.D.; Bosque-Pérez, N.A.; Davis, T.S. Insect-borne plant pathogens and their vectors: Ecology, evolution, and complex interactions. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2018, 63, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, L.R.; Beard, C.B.; Visser, S.N. Combatting the increasing threat of vector-borne disease in the United States with a national vector-borne disease prevention and control system. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 100, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wilson, A.L.; Courtenay, O.; Kelly-Hope, L.A.; Scott, T.W.; Takken, W.; Torr, S.J.; Lindsay, S.W. The importance of vector control for the control and elimination of vector-borne diseases. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0007831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, C.X.; Li, W.B.; Ayres, A.J.; Hartung, J.S.; Miranda, V.S.; Teixeira, D.C. Distribution of Xylella fastidiosa in citrus rootstocks and transmission of citrus variegated chlorosis between sweet orange plants through natural root grafts. Plant Dis. 2000, 84, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderlin, R.S.; Melanson, R.A. Transmission of Xylella fastidiosa through pecan rootstock. HortScience 2006, 41, 1455–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burckhardt, D. Biology, ecology, and evolution of gall-inducing psyllids (Hemiptera: Psylloidea). In Biology, Ecology and Evolution of Gall-Inducing Arthropods; Raman, A., Schaefer, C.W., Withers, T.M., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; Volume 2, pp. 143–157. [Google Scholar]

- Burckhardt, D.; Ouvrard, D.; Queiroz, D.; Percy, D. Psyllid host-plants (Hemiptera: Psylloidea): Resolving a semantic problem. Fla. Entomol. 2014, 97, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flory, S.L.; Mattingly, W.B. Response of host plants to periodical cicada oviposition damage. Oecologia 2008, 156, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baser, N.; Broutou, O.; Lamaj, F.; Verrastro, V.; Porcelli, F. First finding of Drosophila suzukii (Matsumura) (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in Apulia, Italy, and its population dynamics throughout the year. Fruits 2015, 70, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baser, N.; Broutou, O.; Verrastro, V.; Porcelli, F.; Ioriatti, C.; Anfora, G.; Mazzoni, V.; Rossi Stacconi, M.V. Susceptibility of table grape varieties grown in south-eastern Italy to Drosophila suzukii. J. Appl. Entomol. 2018, 142, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salerno, M.; Mazzeo, G.; Suma, P.; Russo, A.; Diana, L.; Pellizzari, G.; Porcelli, F. Aspidiella hartii (Cockerell 1895) (Hemiptera: Diaspididae) on yam (Dioscorea spp.) tubers: A new pest regularly entering the European part of the EPPO region. EPPO Bull. 2018, 48, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouslama, T.; Chaieb, I.; Jerbi-Elayed, M.; Laarif, A. Observations of some biological characteristics of Helicoverpa armigera reared under controlled conditions. Tunis. J. Plant. Prot. 2019, 14, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Arbogast, R.T.; Kendra, P.E.; Mankin, R.W.; McGovern, J.E. Monitoring insect pests in retail stores by trapping and spatial analysis. J. Econ. Entomol. 2000, 93, 1531–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardaro, R.; Grittani, R.; Scrascia, M.; Pazzani, C.; Russo, V.; Garganese, F.; Porfido, C.; Diana, L.; Porcelli, F. The Red Palm Weevil in the City of Bari: A First Damage Assessment. Forests 2018, 9, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sardaro, R.; Roselli, L.; Grittani, R.; Scrascia, M.; Pazzani, C.; Russo, V.; Garganese, F.; Porfido, C.; Diana, L.; Porcelli, F. Community preferences for the preservation of Canary Palm from Red Palm Weevil in the city of Bari. Arab. J. Plant. Prot. 2019, 37, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, C.C.; Luckhart, S.; Cator, L.J. Immunity, host physiology, and behaviour in infected vectors. Curr. Opin. Insect. Sci. 2017, 20, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perilla-Henao, L.M.; Casteel, C.L. Vector-borne bacterial plant pathogens: Interactions with hemipteran insects and plants. Front. Plant. Sci. 2016, 7, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.C.K.; Falk, B.W. Virus-vector interactions mediating nonpersistent and semipersistent transmission of plant viruses. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2006, 44, 183–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.C.K.; Zhou, J.S. Insect vector-plant virus interactions associated with non-circulative, semi-persistent transmission: Current perspectives and future challenges. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2015, 15, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hill, B.L.; Purcell, A.H. Acquisition and retention of Xylella fastidiosa by an efficient vector, Graphocephala atropunctata. Phytopathology 1995, 85, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruening, G.; Kirkpatrick, B.; Esser, T.; Webster, R. Managing newly established pests: Cooperative efforts contained spread of Pierce’s disease and found genetic resistance. Calif. Agric. 2014, 68, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Almeida, R.P. Ecology of emerging vector-borne plant diseases. In Vector-Borne Diseases: Understanding the Environmental, Human Health, and Ecological Connections; Lemon, S.M., Sparling, P.F., Hamburg, M.A., Relman, D.A., Choffnes, E.R., Rapporteurs, A.M., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; pp. 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, K.; Van der Werf, W.; Cendoya, M.; Mourits, M.; Navas-Cortés, J.A.; Vicent, A.; Lansink, A.O. Impact of Xylella fastidiosa subspecies pauca in European olives. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 9250–9259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fierro, A.; Liccardo, A.; Porcelli, F. A lattice model to manage the vector and the infection of the Xylella fastidiosa on olive trees. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liccardo, A.; Fierro, A.; Garganese, F.; Picciotti, U.; Porcelli, F. A biological control model to manage the vector and the infection of Xylella fastidiosa on olive trees. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazier, N.W. Xylem viruses and their insect vectors. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Virus and Vector on Perennial Hosts, Davis, CA, USA, 6–10 September 1965; pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Elbeaino, T.; Valentini, F.; Abou Kubaa, R.; Moubarak, P.; Yaseen, T.; Digiaro, M. Multilocus sequence typing of Xylella fastidiosa isolated from olive affected by “olive quick decline syndrome” in Italy. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2014, 53, 533–542. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Moussa, I.E.; Mazzoni, V.; Valentini, F.; Yaseen, T.; Lorusso, D.; Speranza, S.; Digiaro, M.; Varvaro, L.; Krugner, R.; D’Onghia, A.M. Seasonal Fluctuations of Sap-Feeding Insect Species Infected by Xylella fastidiosa in Apulian Olive Groves of Southern Italy. J. Econ. Entomol. 2016, 109, 1512–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butter, N.S. Insect Vectors and Plant Pathogens; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; p. 496. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell, A.H.; Finlay, A.H. Evidence for noncirculative transmission of Pierce’s disease bacterium by sharpshooter leafhoppers. Phytopathology 1979, 69, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzavolta, T.; Bracalini, M.; Croci, F.; Ghelardini, L.; Luti, S.; Campigli, S.; Goti, E.; Marchi, R.; Tiberi, R.; Marchi, G. Philaenus italosignus a potential vector of Xylella fastidiosa: Occurrence of the spittlebug on olive trees in Tuscany. Bull. Insectol. 2019, 72, 317–320. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, A.J.; Lees, D.R. The colour/pattern polymorphism of Philaenus spumarius (L.) (Homoptera: Cercopidae) in England and Wales. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1996, 351, 69–89. [Google Scholar]

- Drosopoulos, S.; Remane, R. Biogeographic studies on the spittlebug Philaenus signatus Melichar, 1896 species group (Hemiptera: Aphrophoridae) with the description of two new allopatric species. Ann. Soc. Entomol. Fr. 2000, 36, 269–277. [Google Scholar]

- Sandanayaka, M.R.M.; Nielsen, M.; Davis, V.A.; Butler, R.C. Do spittlebugs feed on grape? Assessing transmission potential for Xylella fastidiosa. N. Z. Plant Prot. 2017, 70, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farish, D.J. Balanced polymorphism in North American populations of the meadow spittlebug, Philaenus spumarius (Homoptera: Cercopidae). 1. North American morphs. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1972, 65, 710–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stewart, A.J.A.; Lees, D.R. Genetic control of colour/pattern polymorphism in British populations of the spittlebug Philaenus spumarius (L.) (Homoptera: Aphrophoridae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. Lond. 1988, 34, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtsever, S. On the polymorphic meadow spittlebug, Philaenus spumarius (L.) (Homoptera: Cercopidae). Turk. Zool. Derg. 2000, 24, 447–460. [Google Scholar]

- Drosopoulos, S.; Maryańska-Nadachowska, A.; Kuznetsova, V.G. The Mediterranean: Area of origin of polymorphism and speciation in the spittlebug Philaenus (Hemiptera, Aphrophoridae). Zoosyst. Evol. 2010, 86, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witsack, W. Experimental and ecological investigations on forms of dormancy in Homoptera-Cicadina (Auchenorrhyncha). On ovarian parapause and obligatory embryonic diapause in Philaenus spumarius (L.) (Aphrophoridae). Zool. Jahrb. Abt. Anat. Ontog. Tiere 1973, 100, 517–562. [Google Scholar]

- Masters, G.J.; Brown, V.K.; Clarke, I.P.; Whittaker, J.B.; Hollier, J.A. Direct and indirect effects of climate change on insect herbivores: Auchenorrhyncha (Homoptera). Ecol. Entomol. 1998, 23, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albre, J.; Carrasco, J.M.G.; Gibernau, M. Ecology of the meadow spittlebug Philaenus spumarius in the Ajaccio region (Corsica)–I: Spring. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2020, 111, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karban, R.; Huntzinger, M. Decline of meadow spittlebugs, a previously abundant insect, along the California coast. Ecology 2018, 99, 2614–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Drosopoulos, S.; Asche, M. Biosystematic studies on the spittlebug genus Philaenus with the description of a new species. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 1991, 101, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Nour, H.; Lahoud, L. Revision du genre Philaenus Stål, 1964 au Liban avec la description d’une nouvelle espece: P. arslani, n. sp. (Homoptera, Auchenorrhyncha, Cercopidae). Nouv. Rev. Entomol. 1995, 12, 297–303. [Google Scholar]

- Lahbib, N.; Boukhris-Bouhachem, S.; Cavalieri, V.; Rebha, S.; Porcelli, F. A survey of the possible insect vectors of the bacterium Xylella fastidiosa in seven regions of Tunisia. In Proceedings of the II European Conference on Xylella fastidiosa: How Research Can Support Solutions, Poster Section, Ajaccio, France, 29–30 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Boukhris-Bouhachem, S.; Souissi, R.; Porcelli, F. Taxonomy and re-description of Philaenus Mediterranean species. In Proceedings of the II European Conference on Xylella fastidiosa: How Research Can Support Solutions, Poster Section, Ajaccio, France, 29–30 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Drosopoulos, S. New data on the nature and origin of colour polymorphism in the spittlebug genus Philaenus (Hemiptera: Aphorophoridae). Ann. Soc. Entomol. Fr. 2003, 39, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remane, R.; Drosopoulos, S. Philaenus tarifa nov. sp.—An additional spittlebug from Southern Spain (Homoptera—Cercopidae). Mitt. Mus. Nat. Berl. Dtsch. Entomol. Z. 2001, 48, 277–279. [Google Scholar]

- Kapantaidaki, D.E.; Antonatos, S.; Evangelou, V.; Papachristos, D.P.; Milonas, P. Genetic and endosymbiotic diversity of Greek populations of Philaenus spumarius, Philaenus signatus and Neophilaenus campestris, vectors of Xylella fastidiosa. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; McMahon, T.A. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Broecker, W.S.; Denton, G.H.; Edwards, R.L.; Cheng, H.; Alley, R.B.; Putnam, A.E. Putting the Younger Dryas cold event into context. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2010, 29, 1078–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craw, R.C.; Grehan, J.R.; Heads, M.J. Panbiogeography Tracking the History of Life; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Maryańska-Nadachowska, A.; Kuznetsova, V.G.; Lachowska, D.; Drosopoulos, S. Mediterranean species of the spittlebug genus Philaenus: Modes of chromosome evolution. J. Insect Sci. 2012, 12, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Calviño, C.I.; Martínez, S.G.; Downie, S.R. The evolutionary history of Eryngium (Apiaceae, Saniculoideae): Rapid radiations, long distance dispersals, and hybridizations. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2008, 46, 1129–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, A.S.; Silva, S.E.; Marabuto, E.; Silva, D.N.; Wilson, M.R.; Thompson, V.; Yurtsever, S.; Halkka, A.; Borges, P.A.V.; Quartau, J.A.; et al. New mitochondrial and nuclear evidences support recent demographic expansion and an atypical phylogeographic pattern in the spittlebug Philaenus spumarius (Hemiptera, Aphrophoridae). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodrigues, A.S. Evolutionary History of Philaenus spumarius (Hemiptera, Aphrophoridae) and the Adaptive Significance and Genetic Basis of its Dorsal Colour Polymorphism. Ph.D. Thesis, Lisboa University, Lisboa, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ossiannilsson, F. The Auchenorrhyncha (Homoptera) of Fennoscandia and Denmark. Part 2: The families Cicadidae, Cercopidae, Membracidae, and Cicadellidae (excl. Deltocephalinae). Fauna Entomol. Scand. 1981, 7, 223–593. [Google Scholar]

- Ranieri, E.; Ruschioni, S.; Riolo, P.; Isidoro, N.; Romani, R. Fine structure of antennal sensilla of the spittlebug Philaenus spumarius L. (Insecta: Hemiptera: Aphrophoridae). I. Chemoreceptors and thermos-hygroreceptors. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2016, 45, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germinara, G.S.; Ganassi, S.; Pistillo, M.O.; Di Domenico, C.; De Cristofaro, A.; Di Palma, A.M. Antennal olfactory responses of adult meadow spittlebug, Philaenus spumarius, to volatile organic compounds (VOCs). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0190454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weaver, C.R.; King, D.R. Meadow spittlebug, Philaenus leucophthalmus (L.). Res. Bull. Ohio Agric. Exp. Stn. 1954, 741, 1–99. [Google Scholar]

- Goetzke, H.H.; Pattrick, J.G.; Federle, W. Froghoppers jump from smooth plant surfaces by piercing them with sharp spines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 3012–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beutel, R.G.; Friedrich, F.; Yang, X.K.; Ge, S.Q. Insect Morphology and Phylogeny: A Textbook for Students of Entomology; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2013; p. 513. [Google Scholar]

- Elbeaino, T.; Yaseen, T.; Valentini, F.; Ben Moussa, I.E.; Mazzoni, V.; D’Onghia, A.M. Identification of three potential insect vectors of Xylella fastidiosa in southern Italy. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2014, 53, 328–332. [Google Scholar]

- Lago, C.; Morente, M.; De las Heras-Bravo, D.; Marti-Campoy, A.; Rodriguez-Ballester, F.; Plaza, M.; Moreno, A.; Fereres, A. Dispersal ability of Neophilaenus campestris, a vector of Xylella fastidiosa, from olive groves to over-summering hosts. J. Appl. Entomol. 2021, 145, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, J.B. Density regulation in a population of Philaenus spumarius (L.) (Homoptera: Cercopidae). J. Anim. Ecol. 1973, 42, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecil, R. A Biological and Morphological Study of a Cercopid, Philaenus leucophthalmus (L.). Ph.D. Thesis, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Mundinger, F.G. The control of spittle insects in strawberry plantings. J. Econ. Entomol. 1946, 39, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegert, R.G. Population Energetics of Meadow Spittlebugs (Philaenus spumarius L.) as Affected by Migration and Habitat. Ecol. Monogr. 1964, 34, 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafatos, F.C.; Regier, J.C.; Mazur, G.D.; Nadel, M.R.; Blau, H.M.; Petri, W.H.; Wyman, A.R.; Gelinas, R.E.; Moore, P.B.; Paul, M.; et al. The eggshell of insects: Differentiation-specific proteins and the control of their synthesis and accumulation during development. In Biochemical Differentiation in Insect Glands; Beermann, W., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1977; pp. 45–145. [Google Scholar]

- Halkka, O.; Raatikainen, M.; Vasarainen, A.; Heinonen, L. Ecology and ecological genetics of Philaenus spumarius (L.) (Homoptera). Ann. Zool. Fenn. 1967, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Stöckmann, M.; Biedermann, R.; Nickel, H.; Niedringhaus, R. The Nymphs of the Planthoppers and Leafhoppers of Germany; WABW Fründ: Bremen, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Di Serio, F.; Bodino, N.; Cavalieri, V.; Demichelis, S.; Di Carolo, M.; Dongiovanni, C.; Fumarola, G.; Gilioli, G.; Guerrieri, E.; Picciotti, U.; et al. Collection of data and information on biology and control of vectors of Xylella fastidiosa. EFSA Support. Publ. 2019, 16, 1628E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Neinhuis, C.; Barthlott, W. Wettability and contaminability of insect wings as a function of their surface sculptures. Acta Zool. 1996, 77, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickel, H.; Remane, R. Check list of the planthoppers and leafhoppers of Germany, with notes on food plants, diet width, life cycles, geographic range and conservation status (Hemiptera, Fulgoromorpha and Cicadomorpha). Beiträge Zur Zikadenkunde 2002, 5, 27–64. [Google Scholar]

- Halkka, A.; Halkka, L.; Halkka, O.; Roukka, K.; Pokki, J. Lagged effects of North Atlantic Oscillation on spittlebug Philaenus spumarius (Homoptera) abundance and survival. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2006, 12, 2250–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodino, N.; Cavalieri, V.; Dongiovanni, C.; Plazio, E.; Saladini, M.A.; Volani, S.; Simonetto, A.; Fumarola, G.; Di Carolo, M.; Porcelli, F.; et al. Phenology, seasonal abundance and stage-structure of spittlebug (Hemiptera: Aphrophoridae) populations in olive groves in Italy. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, Z.M.; Jones, P.L. The Effects of Host Plant Species and Plant Quality on Growth and Development in the Meadow Spittlebug (Philaenus spumarius) on Kent Island in the Bay of Fundy. Northeast. Nat. 2020, 27, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernays, E.A.; Graham, M. On the evolution of host specificity in phytophagous arthropods. Ecology 1988, 69, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, U. Growth stages of mono-and dicotyledonous plants. In BBCH Monograph, 2nd ed.; Federal Biological Research Centre for Agriculture and Forestry: Berlin, Germany, 2001; pp. 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, G.; Ellis, W.O. Eggs of three Cercopidae. Psyche 1922, 29, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Medler, J.T. Method of predicting the hatching date of the meadow spittlebug. J. Econ. Entomol. 1955, 48, 204–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picciotti, U.; D’Accolti, A.; Garganese, F.; Gammino, R.P.; Tucci, V.; Russo, V.; Diana, F.; Salerno, M.; Diana, L.; Porfido, C.; et al. Aphrophoridae (Hemiptera) vectors of Xylella fastidiosa pauca OQDS juvenile quantitative sampling. In Proceedings of the XI European Congress of Entomology, Naples, Italy, 2–6 July 2018; pp. 162–163. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, J.F.; Lambdin, P.L.; Follum, R.A. Infestation levels and seasonal incidence of the meadow spittlebug (Homoptera: Cercopidae) on musk thistle in Tennessee. J. Agric. Entomol. 1998, 15, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, M.J.; Kieffer, D.L.; Abrahamson, W.G. Costs and benefits of gregarious feeding in the meadow spittlebug, Philaenus spumarius. Ecol. Entomol. 2006, 31, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilbeau, B.H. The origin and formation of the froth in spittle-insects. Am. Nat. 1908, 42, 783–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malykh, Y.N.; Krisch, B.; Gerardy-Schahn, R.; Lapina, E.B.; Shaw, L.; Schauer, R. The presence of N-acetylneuraminic acid in Malpighian tubules of larvae of the cicada Philaenus spumarius. Glycoconj. J. 1999, 16, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakitov, R.A. Structure and function of the Malpighian tubules, and related behaviors in juvenile cicadas: Evidence of homology with spittlebugs (Hemiptera: Cicadoidea & Cercopoidea). Zool. Anz. 2002, 241, 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Keskinen, E.; Meyer-Rochow, V.B. Post-embryonic photoreceptor development and dark/light adaptation in the spittle bug Philaenus spumarius (L.) (Homoptera, Cercopidae). Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2004, 33, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Campo, M.L.; King, J.T.; Gronquist, M.R. Defensive and chemical characterization of the froth produced by the cercopid Aphrophora cribrata. Chemoecology 2011, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhong, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, C. Comparative morphology of the distal segments of Malpighian tubules in cicadas and spittlebugs, with reference to their functions and evolutionary indications to Cicadomorpha (Hemiptera: Auchenorrhyncha). Zool. Anz. 2015, 258, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Meyer-Rochow, V.B.; Fereres, A.; Morente, M.; Liang, A.P. The role of biofoam in shielding spittlebug nymphs (Insecta, Hemiptera, Cercopidae) against bright light. Ecol. Entomol. 2018, 43, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, M.; Gomes, G.; Silva, W.D.; Magri, N.T.C.; Vieira, D.M.; Aguiar, C.L. Spittlebugs produce foam as a thermoregulatory adaptation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, K.I.; Robertson, A.B.; Matthews, P.G. Studies on gas exchange in the meadow spittlebug, Philaenus spumarius: The metabolic cost of feeding on, and living in, xylem sap. J. Exp. Biol. 2019, 222, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hamilton, K.G.A. The spittlebugs of Canada, Hemiptera: Cercopidae. In The Insects and Arachnids of Canada; Hamilton, K.G.A., Ed.; Part 10; Agriculture Canada, Research Branch: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Berlese, A. Gli Insetti, Loro Organizzanzione, Sviluppo, Abitudini e Rapporti Coll’uomo; Società Editrice Libraria: Milan, Italy, 1909; Volume 1, pp. 539–540. [Google Scholar]

- Šulc, K. Uber Respiration, Tracheen system, Und Schaumproduction der Schaumcikaden Larven. Z. F. Wiss. Zool. 1911, 99, 147–188. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, A.T. Batelli glands of cercopoid nymphs (Homoptera). Nature 1965, 205, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongiovanni, C.; Altamura, G.; Di Carolo, M.; Fumarola, G.; Saponari, M.; Cavalieri, V. Evaluation of efficacy of different insecticides against Philaenus spumarius L., vector of Xylella fastidiosa in olive orchards in Southern Italy, 2015–2017. Arthropod Manag. Tests 2018, 43, tsy034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bodino, N.; Cavalieri, V.; Dongiovanni, C.; Saladini, M.A.; Simonetto, A.; Volani, S.; Plazio, E.; Altamura, G.; Tauro, D.; Gilioli, G.; et al. Spittlebugs of Mediterranean olive groves: Host-plant exploitation throughout the year. Insects 2020, 11, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malone, M.; Watson, R.; Pritchard, J. The spittlebug Philaenus spumarius feeds from mature xylem at the full hydraulic tension of the transpiration stream. New Phytol. 1999, 143, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiel, S.M.; Wilson, M.C. Estimation of the lower and upper developmental threshold temperatures and duration of the nymphal stages of the meadow spittlebug, Philaenus spumarius. Environ. Entomol. 1979, 8, 682–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.; Lees, D.R. Temperature and egg development in the spittlebug Philaenus spumarius (L.) (Homoptera: Aphrophoridae). Entomologist 1988, 13, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Santoiemma, G.; Tamburini, G.; Sanna, F.; Mori, N.; Marini, L. Landscape composition predicts the distribution of Philaenus spumarius, vector of Xylella fastidiosa, in olive groves. J. Pest. Sci. 2019, 92, 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dongiovanni, C.; Cavalieri, V.; Bodino, N.; Tauro, D.; Di Carolo, M.; Fumarola, G.; Altamura, G.; Lasorella, C.; Bosco, D. Plant selection and population trend of spittlebug immatures (Hemiptera: Aphrophoridae) in olive groves of the Apulia region of Italy. J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halkka, O.; Raatikainen, M.; Halkka, L.; Lokki, J. Factors determining the size and composition of island populations of Philaenus spumarius (L.) (Homoptera). Acta Entomol. Fenn. 1971, 28, 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Burrows, M. Jumping performance of froghopper insects. J. Exp. Biol. 2006, 209, 4607–4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Almeida, R.P. Can Apulia’s olive trees be saved? Science 2016, 353, 346–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Press, M.C.; Whittaker, J.B. Exploitation of the xylem stream by parasitic organisms. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1993, 341, 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Cornara, D.; Panzarino, O.; Santoiemma, G.; Bodino, N.; Loverre, P.; Mastronardi, M.G.; Mattia, C.; de Lillo, E.; Addante, R. Natural area sas reservoir of candidate vectors of Xylella fastidiosa. Bull. Insectology 2021, 74, accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Gargani, E.; Benvenuti, C.; Marianelli, L.; Roversi, P.F.; Ricciolini, M.; Scarpelli, I.; Sacchetti, P.; Nencioni, A.; Rizzo, D.; Strangi, A.; et al. A five-year survey in Tuscany (Italy) and detection of Xylella fastidiosa subspecies multiplex in potential insect vectors, collected in Monte Argentario. J. Zool. 2021, 104, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Theodorou, D.; Koufakis, I.; Thanou, Z.; Kalaitzaki, A.; Chaldeou, E.; Afentoulis, D.; Tsagkarakis, A. Management system affects the occurrence, diversity and seasonal fluctuation of Auchenorrhyncha, potential vectors of Xylella fastidiosa, in the olive agroecosystem. Bull. Insectol. 2021, 74, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Witsack, W. Dormanzformen mitteleuropäischer Zikaden. In Zikaden Leafhoppers, Planthoppers and Cicadas (Insecta: Hemiptera: Auchenorrhyncha); Holzinger, W., Ed.; Oberösterreichische Landesmuseen: Linz, Austria, 2002; pp. 471–482. [Google Scholar]

- Witsack, W. Synchronisation der Entwicklung durch Dormanz und Umwelt an Beispielen von Zikaden (Homoptera Auchenorrhyncha). Mitt. Dtsch. Ges. Allg. Angew. Ent. 1993, 8, 563–567. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, C.R. The Seasonal Behavior of Meadow Spittlebug and Its Relation to a Control Method. J. Econ. Entomol. 1951, 44, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, E.; Veijo, K.; Lindströom, J. Spatially autocorrelated disturbances and patterns in population synchrony. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Biol. 1999, 266, 1851–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Post, E.; Forchhammer, M.C. Synchronization of animal population dynamics by large-scale climate. Nature 2002, 420, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horsfield, D. Evidence for xylem feeding by Philaenus spumarius (L.) (Homoptera: Cercopidae). Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1978, 24, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, J.A. Phytophages of xylem and phloem: A comparison of animal and plant sap-feeders. Adv. Ecol. Res. 1983, 13, 135–234. [Google Scholar]

- Bragard, C.; Dehnen-Schmutz, K.; Di Serio, F.; Gonthier, P.; Jacques, M.A.; Miret, J.A.J.; Justesen, A.F.; MacLeod, A.; Magnusson, C.S.; Milonas, P.; et al. Update of the Scientific Opinion on the risks to plant health posed by Xylella fastidiosa in the EU territory. EFSA J. 2019, 17, 5665. [Google Scholar]

- Saponari, M.; Giampetruzzi, A.; Loconsole, G.; Boscia, D.; Saldarelli, P. Xylella fastidiosa in olive in Apulia: Where we stand. Phytopathology 2019, 109, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ionescu, M.; Zaini, P.A.; Baccari, C.; Tran, S.; da Silva, A.M.; Lindow, S.E. Xylella fastidiosa outer membrane vesicles modulate plant colonization by blocking attachment to surfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E3910–E3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bassler, B.L. How bacteria talk to each other: Regulation of gene expression by quorum sensing. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1999, 2, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.B.; Bassler, B.L. Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001, 55, 165–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Waters, C.M.; Bassler, B.L. Quorum sensing: Cell-to-cell communication in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2005, 21, 319–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fry, S.M.; Milholland, R.D. Multiplication and translocation of Xylella fastidiosa in petioles and stems of grapevine resistant, tolerant, and susceptible to Pierce’s disease. Phytopathology 1990, 80, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colnaghi-Simionato, A.V.; da Silva, D.S.; Lambais, M.R.; Carrilho, E. Characterization of a putative Xylella fastidiosa diffusible signal factor by HRGC-EI-MS. J. Mass Spectrom. 2007, 42, 1375–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killiny, N.; Martinez, R.H.; Dumenyo, C.K.; Cooksey, D.A.; Almeida, R.P.P. The exopolysaccharide of Xylella fastidiosa is essential for biofilm formation, plant virulence, and vector transmission. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2013, 26, 1044–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mendes, J.S.; Santiago, A.S.; Toledo, M.A.; Horta, M.A.; de Souza, A.A.; Tasic, L.; de Souza, A.P. In vitro determination of extracellular proteins from Xylella fastidiosa. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Scala, V.; Pucci, N.; Salustri, M.; Modesti, V.; L’Aurora, A.; Scortichini, M.; Zaccaria, M.; Momeni, B.; Reverberi, M.; Loreti, S. Xylella fastidiosa subsp. pauca and olive produced lipids moderate the switch adhesive versus non-adhesive state and viceversa. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233013. [Google Scholar]

- Sabella, E.; Aprile, A.; Genga, A.; Siciliano, T.; Nutricati, E.; Nicolì, F.; Vergine, M.; Negro, C.; De Bellis, L.; Luvisi, A. Xylem cavitation susceptibility and refilling mechanisms in olive trees infected by Xylella fastidiosa. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cariddi, C.; Saponari, M.; Boscia, D.; De Stradis, A.; Loconsole, G.; Nigro, F.; Porcelli, F.; Potere, O.; Martelli, G.P. Isolation of a Xylella fastidiosa strain infecting olive and oleander in Apulia, Italy. J. Plant. Pathol. 2014, 96, 425–429. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA, P.L.H. Scientific opinion on the risks to plant health posed by Xylella fastidiosa in the EU territory, with the identification and evaluation of risk reduction options. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 3989. [Google Scholar]

- Jeger, M.; Caffier, D.; Candresse, T.; Chatzivassiliou, E.; Dehnen-Schmutz, K.; Gilioli, G.; Grégoire, J.C.; Miret, J.A.J.; McLeod, A.; Navarro, M.N.; et al. Updated pest categorisation of Xylella fastidiosa. EFSA J. 2018, 16, e05357. [Google Scholar]

- Poblete, T.; Camino, C.; Beck, P.S.A.; Hornero, A.; Kattenborn, T.; Saponari, M.; Boscia, D.; Navas-Cortes, J.A.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J. Detection of Xylella fastidiosa infection symptoms with airborne multispectral and thermal imagery: Assessing bandset reduction performance from hyperspectral analysis. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 162, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.E.; Basu, S.; Lee, B.W.; Crowder, D.W. Tri-trophic interactions mediate the spread of a vector-borne plant pathogen. Ecology 2019, 100, e02879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crowder, D.W.; Li, J.; Borer, E.T.; Finke, D.L.; Sharon, R.; Pattemore, D.E.; Medlock, J. Species interactions affect the spread of vector-borne plant pathogens independent of transmission mode. Ecology 2019, 100, e02782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunty, A.; Legendre, B.; de Jerphanion, P.; Juteau, V.; Forveille, A.; Germain, J.F.; Ramel, J.M.; Reynaud, P.; Olivier, V.; Poliakoff, F. Xylella fastidiosa subspecies and sequence types detected in Philaenus spumarius and in infected plants in France share the same locations. Plant. Pathol. 2020, 69, 1798–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquasanta, F.; Bacci, L.; Baser, N.; Carmignano, P.M.; Cavalieri, V.; Cioffi, M.; Convertini, S.; D’Accolti, A.; Dal Maso, E.; Diana, F.; et al. Tradizione e Innovazione nel Controllo del Philaenus spumarius Linnaeus, 1758 (Hemiptera Aphrophoridae). In Proceedings of the Giornate Fitopatologiche, Atti Giornate Fitopatologiche I, Chianciano Terme, Italy, 6–9 March 2018; pp. 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti, M.; Capasso, V.; Montagna, M.; Venturino, E. A mathematical model for Xylella fastidiosa epidemics in the Mediterranean regions. Promoting good agronomic practices for their effective control. Ecol. Model. 2020, 432, 109204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signes-Pont, M.T.; Cortés-Plana, J.J.; Mora, H.; Mollá-Sirvent, R. An epidemic model to address the spread of plant pests. The case of Xylella fastidiosa in almond trees. Kybernetes 2020. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniţa, S.; Capasso, V.; Scacchi, S. Controlling the Spatial Spread of a Xylella Epidemic. Bull. Math. Biol. 2021, 83, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonella, E.; Picciau, L.; Pippinato, L.; Cavagna, B.; Alma, A. Host plant identification in the generalist xylem feeder Philaenus spumarius through gut content analysis. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2020, 168, 890–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dáder, B.; Viñuela, E.; Moreno, A.; Plaza, M.; Garzo, E.; Del Estal, P.; Fereres, A. Sulfoxaflor and natural Pyrethrin with Piperonyl Butoxide are effective alternatives to Neonicotinoids against juveniles of Philaenus spumarius, the european vector of Xylella fastidiosa. Insects 2019, 10, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Almeida, R.P.; Blua, M.J.; Lopes, J.R.; Purcell, A.H. Vector transmission of Xylella fastidiosa: Applying fundamental knowledge to generate disease management strategies. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2005, 98, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.L.; Horton, R.; Cruse, R.M. Tillage effects on soil water retention and pore size distribution of two Mollisols. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1985, 49, 1264–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scortichini, M. Predisposing Factors for “Olive Quick Decline Syndrome” in Salento (Apulia, Italy). Agronomy 2020, 10, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcelli, F. First record of Aleurocanthus spiniferus (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae) in Apulia, Southern Italy. EPPO Bull. 2008, 38, 516–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcelli, F. Nuovo antagonista di Aleurocanthus spiniferus, identificato in Puglia. In Proceedings of the 24th Forum Medicina Vegetale “Integrated Crop Management e cambiamento climatico”, Bari, Italy, 13 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lázaro, E.; Sesé, M.; López-Quílez, A.; Conesa, D.; Dalmau, V.; Ferrer, A.; Vicent, A. Tracking the outbreak: An optimized sequential adaptive strategy for Xylella fastidiosa delimiting surveys. Biol. Invasions 2021, 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Scortichini, M.; Cesari, G. An evaluation of monitoring surveys of the quarantine bacterium Xylella fastidiosa performed in containment and buffer areas of Apulia, southern Italy. Appl. Biosaf. 2019, 24, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatulli, G.; Modesti, V.; Pucci, N.; Scala, V.; L’Aurora, A.; Lucchesi, S.; Salustri, M.; Scortichini, M.; Loreti, S. Further In Vitro Assessment and Mid-Term Evaluation of Control Strategy of Xylella fastidiosa subsp. pauca in Olive Groves of Salento (Apulia, Italy). Pathogens 2021, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, E.M. Effectiveness of the monitoring of X. fastidiosa subsp. pauca in the olive orchards of Southern Italy (Apulia). Rend. Lincei Sci. Fis. Nat. 2019, 30, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, M. Integrated pest management: Historical perspectives and contemporary developments. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 1998, 43, 243–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saponari, M.; Boscia, D.; Altamura, G.; Loconsole, G.; Zicca, S.; D’Attoma, G.; Morelli, M.; Palmisano, F.; Saponari, A.; Tavano, D.; et al. Isolation and pathogenicity of Xylella fastidiosa associated to the olive quick decline syndrome in southern Italy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedigo, L.P.; Rice, M.E. Entomology and Pest Management, 6th ed.; Waveland Press, Inc.: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McCravy, K.W. A review of sampling and monitoring methods for beneficial arthropods in agroecosystems. Insects 2018, 9, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruesink, W.G.; Kogan, M. The quantitative basis of pest management: Sampling and measuring. In Introduction to Insect Pest Management; Metcalf, R.L., Luckmann, W.H., Eds.; Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 309–351. [Google Scholar]

- Schotzko, D.J.; O’Keeffe, L.E. Comparison of Sweep Net., D.-Vac., and Absolute Sampling., and Diel Variation of Sweep Net Sampling Estimates in Lentils for Pea Aphid (Homoptera: Aphididae)., Nabids (Hemiptera: Nabidae)., Lady Beetles (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), and Lacewings (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 1989, 82, 491–506. [Google Scholar]

- Ausden, M.; Drake, M. Invertebrates. In Ecological Census Techniques: A Handbook, 2nd ed.; Sutherland, W.J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 214–289. [Google Scholar]

- Kretzschmar, G.P. Soybean insects in Minnesota with special reference to sampling techniques. J. Econ. Entomol. 1948, 41, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedigo, L.P.; Lentz, G.L.; Stone, J.D.; Cox, D.F. Green Clover worm Populations in Iowa Soybean with Special Reference to Sampling Procedure. J. Econ. Entomol. 1972, 65, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubici, G.; Prigigallo, M.I.; Garganese, F.; Nugnes, F.; Jansen, M.; Porcelli, F. First report of Aleurocanthus spiniferus on Ailanthus altissima: Profiling of the insect microbiome and MicroRNAs. Insects 2020, 11, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lozano-Soria, A.; Picciotti, U.; Lopez-Moya, F.; Lopez-Cepero, J.; Porcelli, F.; Lopez-Llorca, L.V. Volatile organic compounds from entomopathogenic and nematophagous fungi, repel banana black weevil (Cosmopolites sordidus). Insects 2020, 11, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redak, R.A.; Purcell, A.H.; Lopes, J.R.; Blua, M.J.; Mizell III, R.F.; Andersen, P.C. The biology of xylem fluid–feeding insect vectors of Xylella fastidiosa and their relation to disease epidemiology. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 2004, 49, 243–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, K.; Mourits, M.; van der Werf, W.; Oude-Lansinka, A. Analysis on consumer impact from Xylella fastidiosa subspecies pauca. Ecol. Econom. 2021, 185, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, R.; Martinez-Sanchez, L. Monitoring the impact of Xylella on Apulia’s olive orchards using MODIS satellite data supported by weather data. In Proceedings of the 2nd European Conference on Xylella fastidiosa, Ajaccio, France, 29–30 October 2019; Available online: http://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/event/191029-xylella/S6.P1_BECK.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Semeraro, T.; Gatto, E.; Buccolieri, R.; Vergine, M.; Gao, Z.; De Bellis, L.; Luvisi, A. Changes in olive urban forests infected by Xylella fastidiosa: Impact on microclimate and social health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ali, B.M.; van der Werf, W.; Lansink, A.O. Assessment of the environmental impacts of Xylella fastidiosa subsp. pauca in Puglia. Crop. Prot. 2021, 142, 105519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Picciotti, U.; Lahbib, N.; Sefa, V.; Porcelli, F.; Garganese, F. Aphrophoridae Role in Xylella fastidiosa subsp. pauca ST53 Invasion in Southern Italy. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10081035

Picciotti U, Lahbib N, Sefa V, Porcelli F, Garganese F. Aphrophoridae Role in Xylella fastidiosa subsp. pauca ST53 Invasion in Southern Italy. Pathogens. 2021; 10(8):1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10081035

Chicago/Turabian StylePicciotti, Ugo, Nada Lahbib, Valdete Sefa, Francesco Porcelli, and Francesca Garganese. 2021. "Aphrophoridae Role in Xylella fastidiosa subsp. pauca ST53 Invasion in Southern Italy" Pathogens 10, no. 8: 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10081035

APA StylePicciotti, U., Lahbib, N., Sefa, V., Porcelli, F., & Garganese, F. (2021). Aphrophoridae Role in Xylella fastidiosa subsp. pauca ST53 Invasion in Southern Italy. Pathogens, 10(8), 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10081035