Predicting Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Coinfection, Using Supervised Machine Learning Algorithm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting, and Population

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants

3.1.1. Categorization of the Patients According to Their CD4 Lymphocyte Count and Viral Load

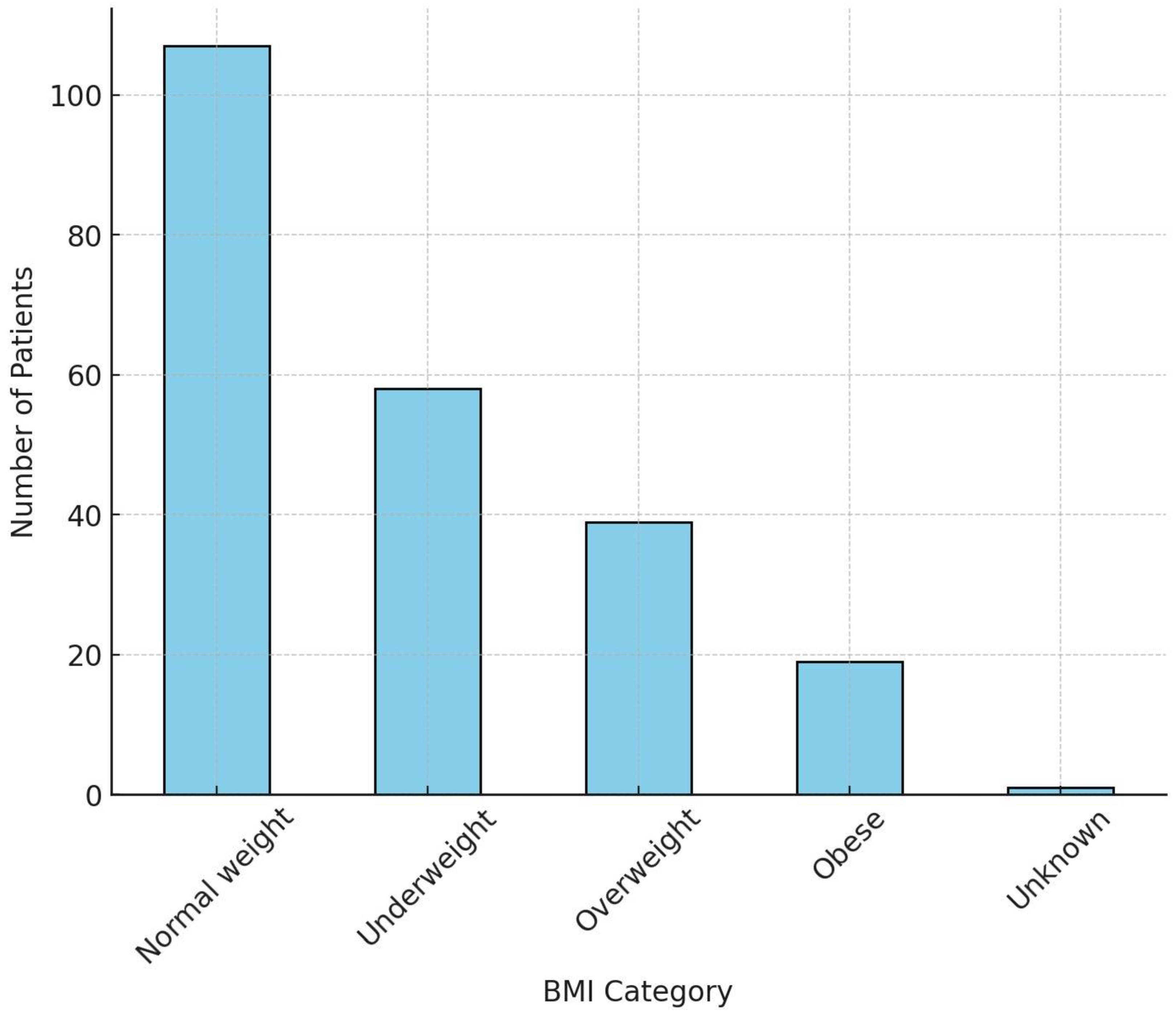

3.1.2. Body Mass Index (BMI) Categorization

3.1.3. Presence of Chronic Comorbidities

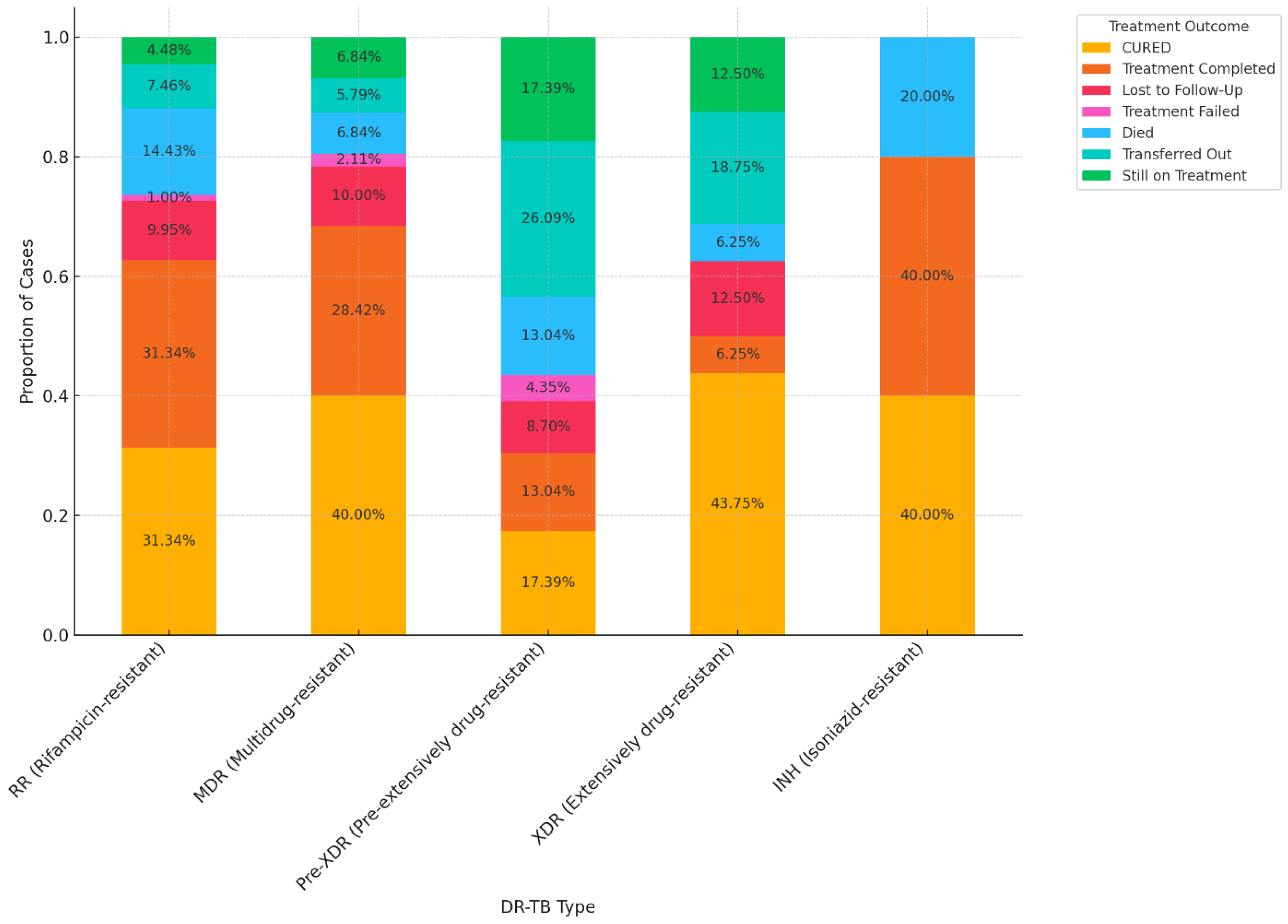

3.2. Treatment Outcomes of DR-TB

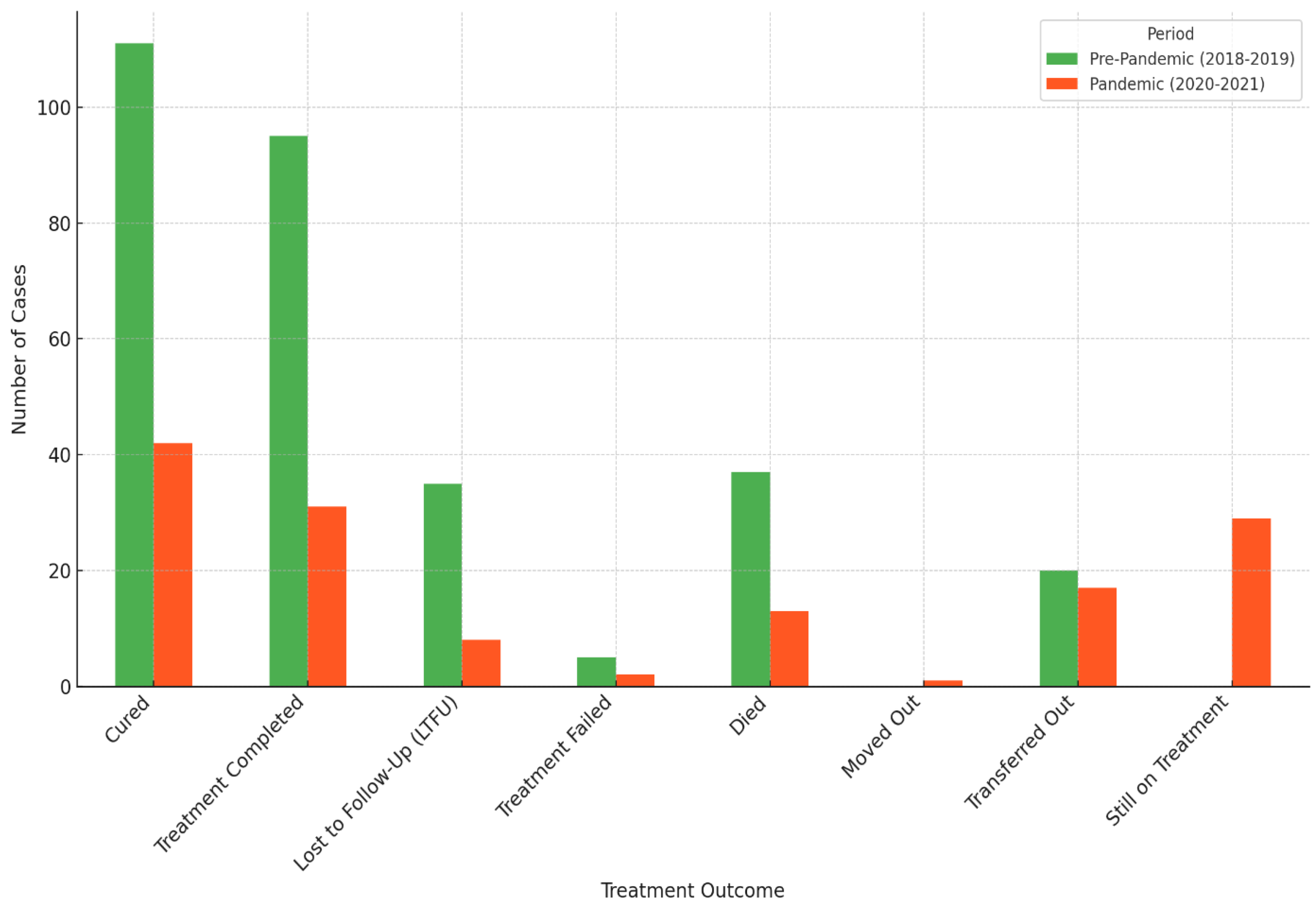

3.3. Treatment Outcomes of DR-TB Comparing COVID-19 Pre-Pandemic (2018–2019) and Pandemic (2020–2021) Periods

3.4. The Trend of Treatment Outcomes over Time

3.5. Association Between DR-TB and Treatment Outcomes

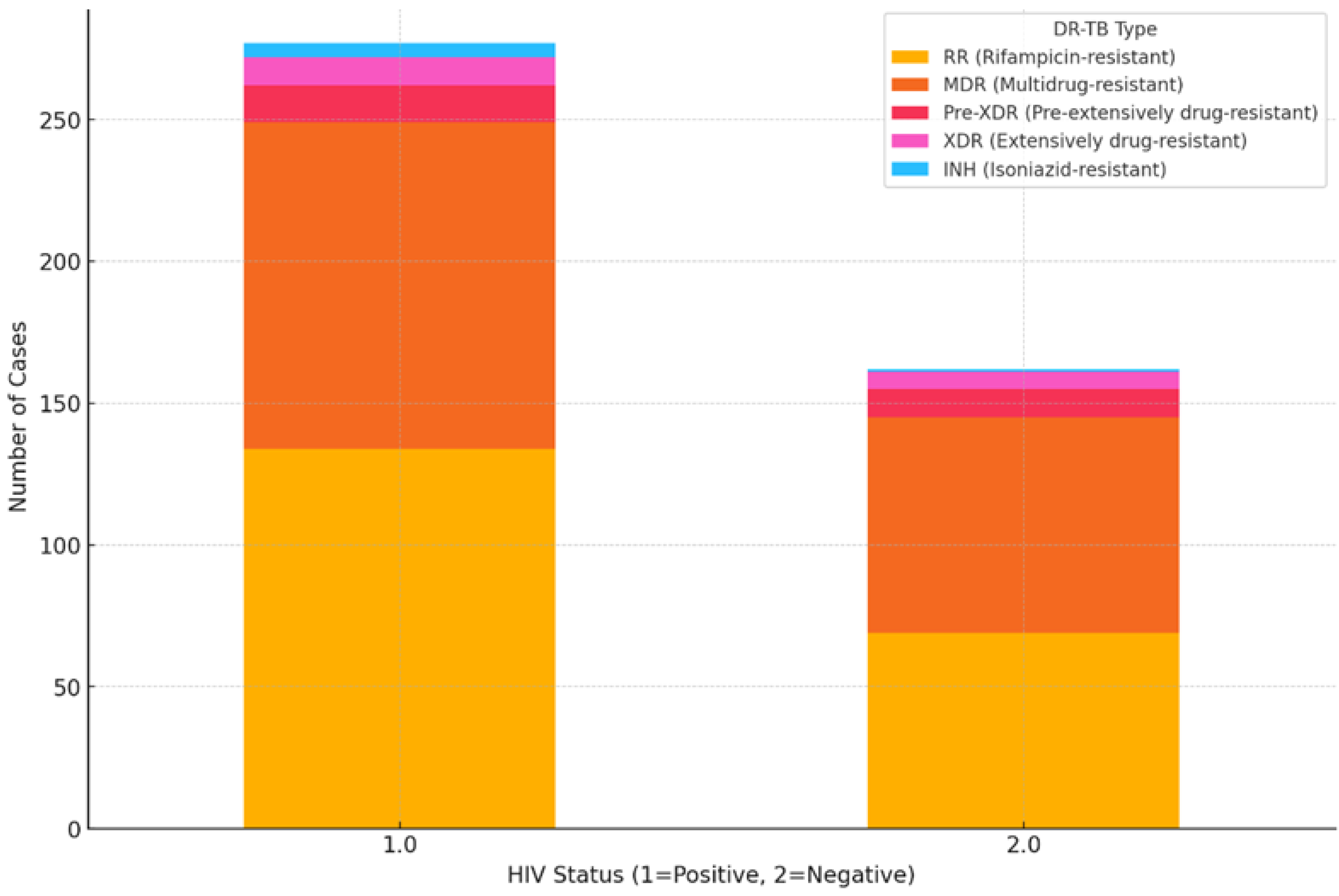

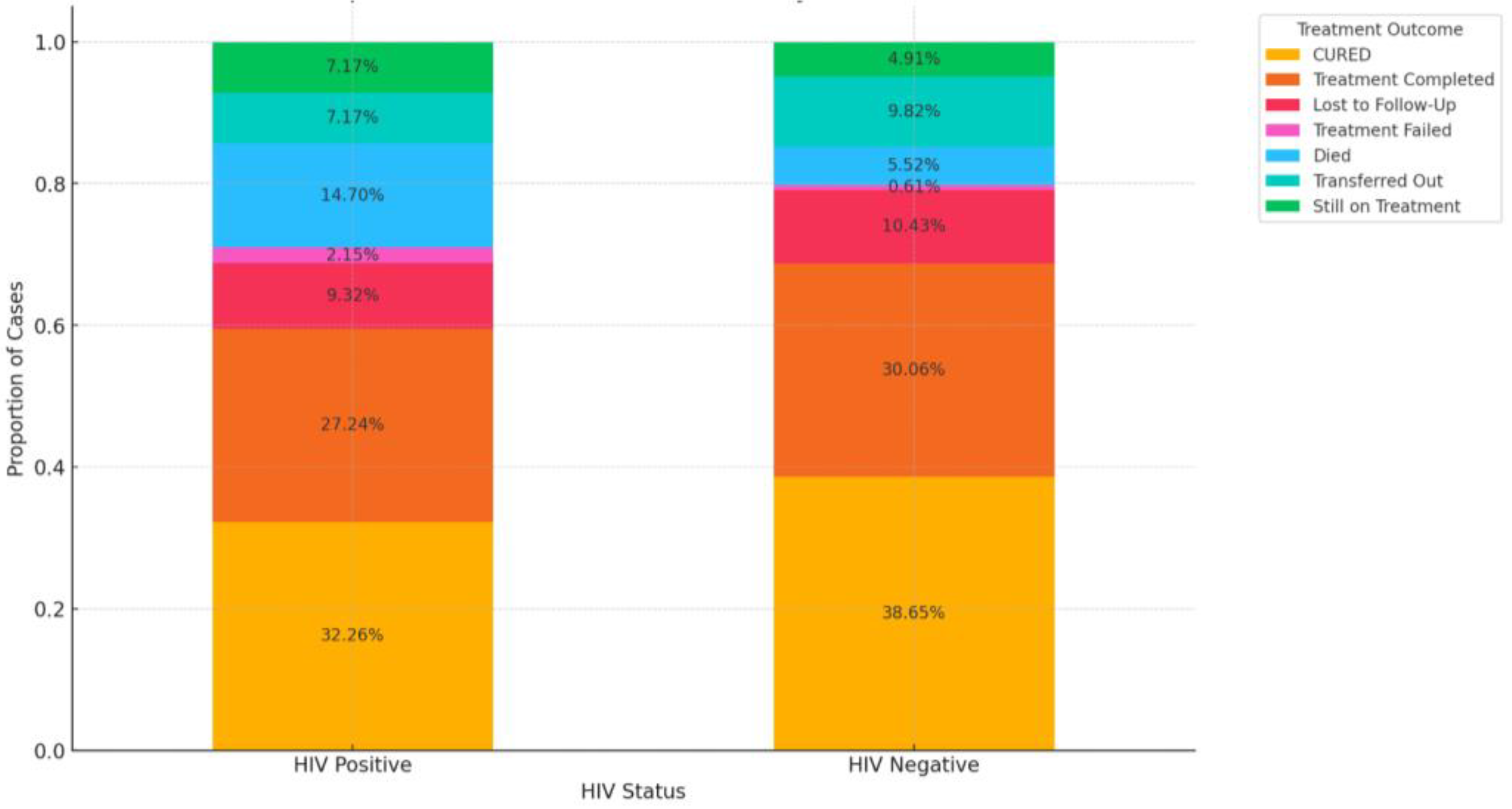

3.6. Impact of HIV Coinfection on Treatment Outcomes

3.7. Factors Influencing Treatment Outcomes

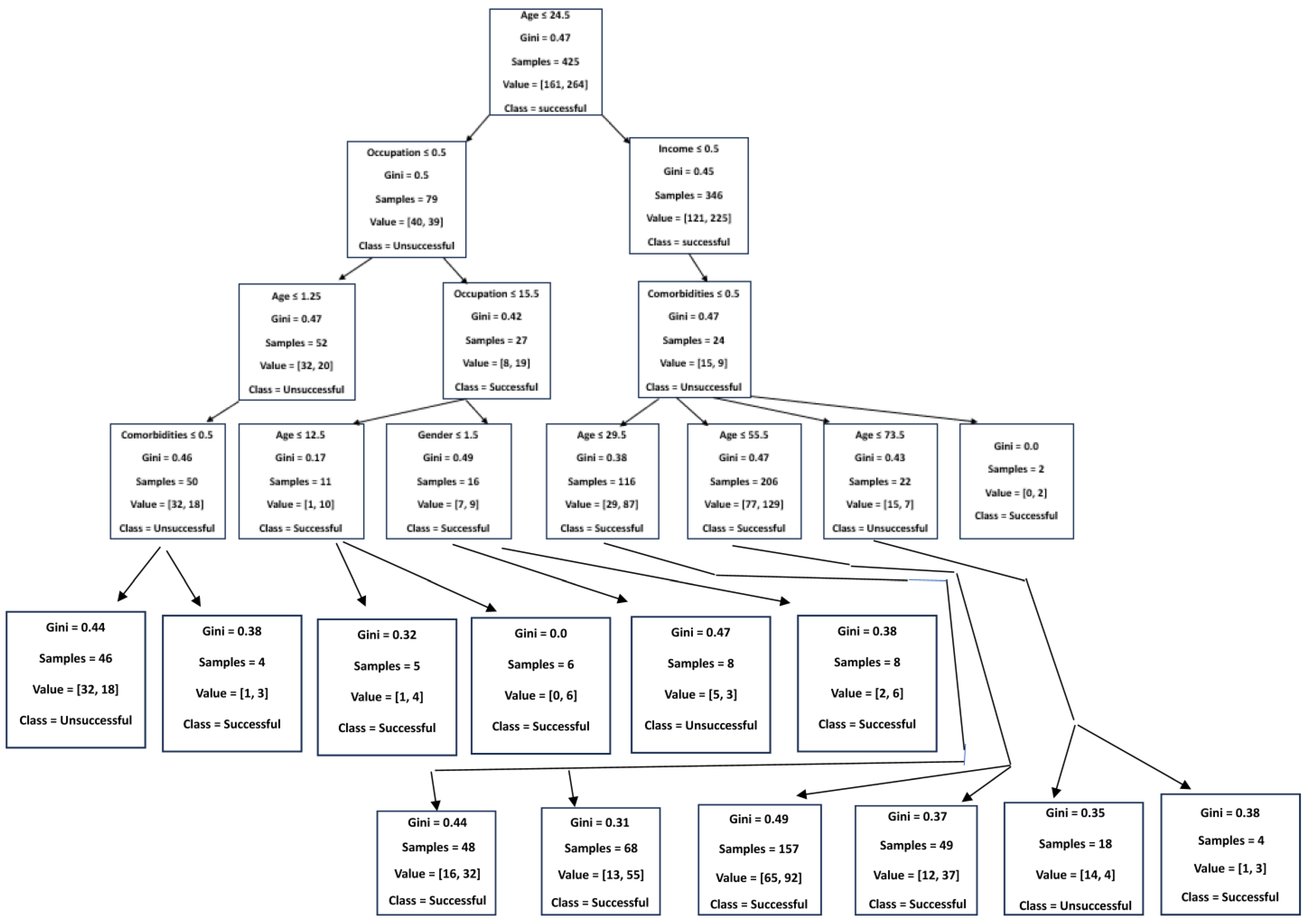

3.8. Predictors of DR-TB Successful Treatment Outcome Using a Decision Tree Classifier (Supervised Machine Learning Algorithm)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Song, W.M.; Guo, J.; Xu, T.T.; Li, S.J.; Liu, J.Y.; Tao, N.N.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Liu, S.Q.; An, Q.Q.; et al. Association between body mass index and newly diagnosed drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis in Shandong, China from 2004 to 2019. BMC Pulm. Med. 2024, 21, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neves, A.C.D.O.J.; Dos Santos, A.P.G.; de Medeiros, R.L.; de Oliveira Jeronymo, A.J.; Neves, G.C.; de Almeida, I.N.; de Queiroz Mello, F.C.; Kritski, A.L. Sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with treatment outcomes for drug-resistant tuberculosis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2022, 107, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2023; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/373828/9789240083851-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 12 August 2024).

- Torres, S.G.V.; Fullmer, J.; Berkowitz, L. A Case of Multidrug-Resistant (MDR) Tuberculosis and HIV Co-Infection. Cureus 2023, 15, e37033. [Google Scholar]

- Chanda, E. The clinical profile and outcomes of drug-resistant tuberculosis in Central Province of Zambia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2021; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240037021 (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Kamara, R.F.; Saunders, M.J.; Sahr, F.; Losa-Garcia, J.E.; Foray, L.; Davies, G.; Wingfield, T. Social and health factors associated with adverse treatment outcomes among people with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Sierra Leone: A national, retrospective cohort study. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e543–e554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, A.; Diallo, B.D.; Camara, L.M.; Kounoudji, L.A.N.; Bah, B.; N’Zabintawali, F.; Carlos-Bolumbu, M.; Diallo, M.H.; Sow, O.Y. Different profiles of body mass index variation among patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daftary, A.; Mondal, S.; Zelnick, J.; Friedland, G.; Seepamore, B.; Boodhram, R.; Amico, K.R.; Padayatchi, N.; O’Donnell, M.R. Dynamic needs and challenges of people with drug-resistant tuberculosis and HIV in South Africa: A qualitative study. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e479–e488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagnew, F.; Alene, K.A.; Kelly, M.; Gray, D. Impacts of body weight change on treatment outcomes in patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Northwest Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, C.; Walzl, G.; Du Plessis, N. Therapeutic host-directed strategies to improve outcome in tuberculosis. Mucosal Immunol. 2020, 13, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, Q.M.; Nguyen, H.L.; Nguyen, V.N.; Nguyen, T.V.A.; Sintchenko, V.; Marais, B.J. Tuberculosis and HIV co-infection—Focus on the Asia-Pacific region. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 32, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zheng, P.; Fu, H. Prevalence of TB/HIV coinfection in countries except China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64915. [Google Scholar]

- Hayibor, K.M.; Bandoh, D.A.; Asante-Poku, A.; Kenu, E. Research Article Predictors of Adverse TB Treatment Outcome among TB/HIV Patients Compared with Non-HIV Patients in the Greater Accra Regional Hospital from 2008 to 2016. Tuberc Res Treat. 2020, 2020, 1097581. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Biadglegne, F.; Anagaw, B.; Debebe, T.; Anagaw, B. A retrospective study on the outcomes of tuberculosis treatment in Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethopia. Int. J. Med. Med. Sci. 2013, 5, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Seid, A.; Girma, Y.; Abebe, A.; Dereb, E.; Kassa, M.; Berhane, N. Characteristics of TB/HIV co-infection and patterns of multidrug-resistance tuberculosis in the Northwest Amhara, Ethiopia. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, 31, 3829–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Global Tuberculosis Report 2015, WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/191102/9789241565059_eng.pdf? (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Singh, A.; Prasad, R.; Balasubramanian, V.; Gupta, N. Drug-resistant tuberculosis and HIV infection: Current perspectives. HIV/AIDS-Res. Palliat. Care 2020, 13, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2019; (WHO/CDS/TB/2019.15); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/ (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Vanleeuw, L.; Loveday, M.; Tuberculosis District Health Barometer. Tuberculosis. Available online: https://www.hst.org.za/publications/District%20Health%20Barometers/9%20(Section%20A)%20Tuberculosis.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Mahtab, S.; Coetzee, D. Influence of HIV and other risk factors on tuberculosis. S. Afr. Med. J. 2017, 107, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrone, M.; Bracchi, M.; Wasserman, S.; Pozniak, A.; Meintjes, G.; Cohen, K.; Wilkinson, R.J. Safety implications of combined antiretroviral and anti-tuberculosis drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2020, 19, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Report: Global Strategy and Targets for Tuberculosis Prevention, Care, and Control After 2015. Available online: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB134/B134_12-en.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- World Health Organization (WHO) Report. The Global Plan to Stop TB 2011–2015. Available online: http://www.stoptb.org/assets/documents/global/plan/TB_GlobalPlanToStopTB2011-2015.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Zumla, A.; Petersen, E.; Nyirenda, T.; Chakaya, J. Tackling the tuberculosis epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa–unique opportunities arising from the second European Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP) programme 2015–2024. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 32, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, J.; Nussinov, R.; Zhang, Y.C.; Cheng, F.; Zhang, Z.K. Computational network biology: Data, models, and applications. Phys. Rep. 2020, 846, 1–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiffer-Smadja, N.; Rawson, T.M.; Ahmad, R.; Buchard, A.; Georgiou, P.; Lescure, F.X.; Birgand, G.; Holmes, A.H. Machine learning for clinical decision support in infectious diseases: A narrative review of current applications. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quazi, S. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in precision and genomic medicine. Med. Oncol. 2022, 39, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lino Ferreira da Silva Barros, M.H.; Oliveira Alves, G.; Morais Florêncio Souza, L.; da Silva Rocha, E.; Lorenzato de Oliveira, J.F.; Lynn, T.; Sampaio, V.; Endo, P.T. Benchmarking machine learning models to assist in the prognosis of tuberculosis. Informatics 2021, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhag, A.A. Prediction and classification of Tuberculosis using machine learning. J. Stat. Appl. Pro. 2024, 13, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, P.; Moodley, D.; Pillay, A.W.; Seebregts, C.J.; Oliveira, T.D. An investigation of classification algorithms for predicting HIV drug resistance without genotype resistance testing. In Foundations of Health Information Engineering and Systems: Third International Symposium, FHIES 2013, Macau, China, 21–23 August 2013; Revised Selected Papers 3, 236–253; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, K.R.; de Carvalho, L.V.F.M.; Reading, B.J.; Fahrenholz, A.; Ferket, P.R.; Grimes, J.L. Machine learning and data mining methodology to predict nominal and numeric performance body weight values using Large White male turkey datasets. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2023, 32, 100366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, G.; Khalilzadeh, O.; Michalski, M.; Do, S.; Samir, A.E.; Pianykh, O.S.; Geis, J.R.; Pandharipande, P.V.; Brink, J.A.; Dreyer, K.J. Current applications and future impact of machine learning in radiology. Radiology 2018, 288, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topol, E.J. High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abràmoff, M.D.; Lavin, P.T.; Birch, M.; Shah, N.; Folk, J.C. Pivotal trial of an autonomous AI-based diagnostic system for detection of diabetic retinopathy in primary care offices. NPJ Digit. Med. 2018, 28, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazzi, M.; Cozzi-Lepri, A. Prosperi MCF. Computer-aided optimization of combined anti-retroviral therapy for HIV: New drugs, new drug targets and drug resistance. Curr. HIV Res. 2016, 14, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macesic, N.; Polubriaginof, F.; Tatonetti, N.P. Machine learning: Novel bioinformatics approaches for combating antimicrobial resistance. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 30, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Satola, S.W.; Read, T.D. Genome-based prediction of bacterial antibiotic resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 57, 10–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrant, J.D.; Amaro, R.E. Machine-learning techniques applied to antibacterial drug discovery. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2015, 85, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.Y.; Lee, M.W.; Fulan, B.M.; Ferguson, A.L.; Wong, G.C.L. What can machine learning do for antimicrobial peptides, and what can antimicrobial peptides do for machine learning? Interface Focus 2017, 7, 20160153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sips, M.E.; Bonten, M.J.M.; van Mourik, M.S.M. Automated surveillance of healthcare-associated infections: State of the art. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 30, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, J.A.; Battegay, M.; Juchler, F.; Vogt, J.E.; Widmer, A.F. Introduction to machine learning in digital healthcare epidemiology. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2018, 39, 1457–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evora, L.H.R.A.; Seixas, J.M.; Kritski, A.L. Neural network models for supporting drug and multidrug resistant tuberculosis screening diagnosis. Neurocomputing 2017, 265, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Bhandari, K.; Sah, S.P.; Anitha, V.; Mane, Y.D.; Punithavel, R.; Banerjee, S. AI in Healthcare: Predicting Patient Outcomes using Machine Learning Techniques. Afr. J. Bio. Sci. 2024, 6, 1847–1861. [Google Scholar]

- Revell, A.D.; Wang, D.; Wood, R.; Morrow, C.; Tempelman, H.; Hamers, R.L.; Alvarez-Uria, G.; Streinu-Cercel, A.; Ene, L.; Wensing, A.M.J.; et al. Computational models can predict response to HIV therapy without a genotype and may reduce treatment failure in different resource-limited settings. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013, 68, 1406–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. Census 2022; Stats SA: Pretoria, South Africa, 2022. Available online: http://www.statssa.gov.za (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- National Department of Health. South African Tuberculosis Treatment Guidelines 2018; National Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- National Department of Health (NdoH) 2019 ART Clinical Guidelines for the Management of HIV in Adults, Pregnancy, Adolecents, Children, Infants and Neonates. Available online: https://www.health.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/2019-art-guideline.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- HIV-Global-World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/hiv-aids#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- WHO Factsheet 2010. A Healthy Lifestyle. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/a-healthy-lifestyle---who-recommendations (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Bisson, G.P.; Bastos, M.; Campbell, J.R.; Bang, D.; Brust, J.C.; Isaakidis, P.; Lange, C.; Menzies, D.; Migliori, G.B.; Pape, J.W.; et al. Mortality in adults with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and HIV by antiretroviral therapy and tuberculosis drug use: An individual patient data meta-analysis. Lancet 2020, 396, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lai, K.; Li, T.; Lin, Z.; Liang, Z.; Du, Y.; Zhang, J. Factors associated with treatment outcomes of patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis in China: A retrospective study using competing risk model. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 906798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panford, V.; Kumah, E.; Kokuro, C.; Adoma, P.O.; Baidoo, M.A.; Fusheini, A.; Ankomah, S.E.; Agyei, S.K.; Agyei-Baffour, P. Treatment outcomes and associated factors among patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Ashanti Region, Ghana: A retrospective, cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e062857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Harakuni, S.; Paranjape, R.; Korabu, A.S.; Prasad, J.B. Factors determining successful treatment outcome among notified tuberculosis patients in Belagavi district of North Karnataka, India. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2024, 25, 101505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhan, A.; Berhan, Y.; Yizengaw, D. A meta-analysis of drug-resistant tuberculosis in Sub-Saharan Africa: How strongly associated with previous treatment and HIV co-infection? Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2013, 23, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nachega, J.B.; Kapata, N.; Sam-Agudu, N.A.; Decloedt, E.H.; Katoto, P.D.; Nagu, T.; Mwaba, P.; Yeboah-Manu, D.; Chanda-Kapata, P.; Ntoumi, F.; et al. Minimizing the impact of the triple burden of COVID-19, tuberculosis and HIV on health services in sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 113, S16–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seloma, N.M.; Makgatho, M.E.; Maimela, E. Evaluation of drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment outcome in Limpopo province, South Africa. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2023, 15, 3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hamdouni, M.; Bourkadi, J.E.; Benamor, J.; Hassar, M.; Cherrah, Y.; Ahid, S. Treatment outcomes of drug-resistant tuberculosis patients in Morocco: Multi-centric prospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2019, 19, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramma, L.; Cox, H.; Wilkinson, L.; Foster, N.; Cunnama, L.; Vassall, A.; Sinanovic, E. Patients’ costs associated with seeking and accessing treatment for drug-resistant tuberculosis in South Africa. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2015, 19, 1513–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.; Ismail, F.; Omar, S.V.; Blows, L.; Gardee, Y.; Koornhof, H. Drug-resistant tuberculosis in Africa: Current status, gaps and opportunities. Afr. J. Lab. Med. 2018, 7, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, G.; Dąbrowska, A.; Pilaczyńska-Cemel, M.; Krawiecka, D. Unemployment in TB patients–ten-year observation at regional center of pulmonology in Bydgoszcz, Poland. Med. Sci. Monit. Inter. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2014, 20, 2125. [Google Scholar]

- Mphande-Nyasulu, F.A.; Puengpipattrakul, P.; Praipruksaphan, M.; Keeree, A.; Ruanngean, K. Prevalence of tuberculosis (TB), including multi-drug-resistant and extensively-drug-resistant TB, and association with occupation in adults at Sirindhorn Hospital, Bangkok. IJID Reg. 2022, 2, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limenh, L.W.; Kasahun, A.E.; Sendekie, A.K.; Seid, A.M.; Mitku, M.L.; Fenta, E.T.; Melese, M.; Workye, M.; Simegn, W.; Ayenew, W. Tuberculosis treatment outcomes and associated factors among tuberculosis patients treated at healthcare facilities of Motta Town, Northwest Ethiopia: A five-year retrospective study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotz, J.K.; Porter, J.D.; Conradie, H.H.; Boyles, T.H.; Gaunt, C.B.; Dimanda, S.; Cort, D. Treating drug-resistant tuberculosis in an era of shorter regimens: Insights from rural South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 2023, 113, 1491–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, L.M.; Hosu, M.C.; Iruedo, J.; Vasaikar, S.; Nokoyo, K.A.; Tsuro, U.; Apalata, T. Treatment outcomes and associated factors among tuberculosis patients from selected rural eastern cape hospitals: An ambidirectional study. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyare, S.A.; Osei, F.A.; Odoom, S.F.; Mensah, N.K.; Amanor, E.; Martyn-Dickens, C.; Owusu-Ansah, M.; Mohammed, A.; Yeboah, E.O. Treatment Outcomes and Associated Factors in Tuberculosis Patients at Atwima Nwabiagya District, Ashanti Region, Ghana: A Ten-Year Retrospective Study. Tuberc. Res. Treat. 2021, 2021, 9952806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sariem, C.N.; Odumosu, P.; Dapar, M.P.; Musa, J.; Ibrahim, L.; Aguiyi, J. Tuberculosis treatment outcomes: A fifteen-year retrospective study in Jos-North and Mangu, Plateau State, North-Central Nigeria. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofoegbu, O.S.; Odume, B.B. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients at National Hospital Abuja Nigeria: A five-year retrospective study. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2015, 57, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getie, A.; Alemnew, B. Tuberculosis treatment outcomes and associated factors among patients treated at Woldia General Hospital in NortheastEthiopia: An institution-based cross-sectional study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 3423–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanue, E.A.; Nsagha, D.S.; Njamen, T.N.; Assob, N.J.C. Tuberculosis treatment outcome and its associated factors among people living with HIV and AID in Fako Division of Cameroon. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapata, N.; Grobusch, M.P.; Chongwe, G.; Chanda-Kapata, P.; Ngosa, W.; Tembo, M.; Musonda, S.; Katemangwe, P.; Bates, M.; Mwaba, P.; et al. Outcomes of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Zambia: A cohort analysis. Infection 2017, 45, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soedarsono, S.; Mertaniasih, N.M.; Kusmiati, T.; Permatasari, A.; Juliasih, N.N.; Hadi, C.; Alfian, I.N. Determinant factors for loss to follow-up in drug-resistant tuberculosis patients: The importance of psycho-social and economic aspects. BMC Pulm. Med. 2021, 21, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepoju, V.A.; Adelekan, A.; Adejumo, A.O. Timing and reasons for lost to follow-up among patients on 6-month standardized anti-TB treatment in Nigeria. J. Pre-Clin. Clin. Res. 2022, 16, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO) African Region. Low Funding, COVID-19 Curtail Tuberculosis Fight in Africa. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/news/low-funding-covid-19-curtail-tuberculosis-fight-africa (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Abdul, J.B.P.A.A.; Adegbite, B.R.; Ndanga, M.E.D.; Edoa, J.R.; Mevyann, R.C.; Mfoumbi, G.R.A.I.; De Dieu, T.J.; Mahoumbou, J.; Biyogho, C.M.; Jeyaraj, S.; et al. Resistance patterns among drug-resistant tuberculosis patients and trends-over-time analysis of national surveillance data in Gabon, Central Africa. Infection 2023, 51, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabunda, T.E.; Ramalivhana, N.J.; Dambisya, Y.M. Mortality associated with tuberculosis/HIV co-infection among patients on TB treatment in the Limpopo province, South Africa. Afr. Health Sci. 2014, 14, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Alemu, M.A.; Yesuf, A.; Girma, F.; Adugna, F.; Melak, K.; Biru, M.; Seyoum, M.; Abiye, T. Impact of HIV-AIDS on tuberculosis treatment outcome in Southern Ethiopia–a retrospective cohort study. J. Clin. Tuberc. Other Mycobact. Dis. 2021, 25, 100279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngari, M.M.; Rashid, M.A.; Sanga, D.; Mathenge, H.; Agoro, O.; Mberia, J.K.; Katana, G.G.; Vaillant, M.; Abdullahi, O.A. Burden of HIV and treatment outcomes among TB patients in rural Kenya: A 9-year longitudinal study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Werf, M.J.; Ködmön, C.; Zucs, P.; Hollo, V.; AmatoGauci, A.J.; Pharris, A. Tuberculosis and HIV coinfection in Europe. AIDS 2016, 30, 2845–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, E.; Der, J.; Owusu, R.; Kofie, P.; Axame, W.K. The burden of HIV on tuberculosis patients in the Volta region of Ghana from 2012 to 2015: Implication for tuberculosis control. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karo, B.; Krause, G.; Hollo, V.; van der Werf, M.J.; Castell, S.; Hamouda, O.; Haas, W. Impact of HIV infection on treatment outcome of tuberculosis in Europe. AIDS 2016, 30, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogun, O.S.; Olaleye, S.A.; Mohsin, M.; Toivanen, P. Investigating machine learning methods for tuberculosis risk factors prediction: A comparative analysis and evaluation. In Proceedings of the 37th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), Cordoba, Spain, 1–2 April 2021; ISBN 978-0-9998551-6-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kalhori, S.R.N.; Zeng, X.J. Evaluation and comparison of different machine learning methods to predict outcome of tuberculosis treatment course. J. Intell. Learn. Syst. Appl. 2013, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kubjane, M.; Osman, M.; Boulle, A.; Johnson, L.F. The impact of HIV and tuberculosis interventions on South African adult tuberculosis trends, 1990–2019: A mathematical modeling analysis. Inter. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 122, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchyard, G.J.; Mametja, L.D.; Mvusi, L.; Ndjeka, N.; Pillay, Y.; Hesseling, A.C.; Reid, A.; Babatunde, S. Tuberculosis control in South Africa: Successes, challenges and recommendations: Tuberculosis control—Progress towards the Millennium Development Goals. S. Afr. Med. J. 2014, 104, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele, H.T.; Van Mourik, M.S.M.; Debray, T.P.A.; Bonten, M.J.M. Isoniazid prophylactic therapy for the prevention of tuberculosis in HIV infected adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, J.M.; Badje, A.; Rangaka, M.X.; Walker, A.S.; Shapiro, A.E.; Thomas, K.K.; Anglaret, X.; Eholie, S.; Gabillard, D.; Boulle, A.; et al. Isoniazid preventive therapy plus antiretroviral therapy for the prevention of tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet HIV 2021, 8, e8–e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 256 | 56.1 |

| Female | 200 | 43.9 |

| Age groups (years) | ||

| 0–18 | 32 | 7.2 |

| 19–35 | 185 | 41.6 |

| 36–50 | 142 | 31.9 |

| 51–65 | 65 | 14.6 |

| >66 | 21 | 4.7 |

| Occupation | ||

| Unemployed | 331 | 76.3 |

| Employed (govt. and private) | 34 | 7.8 |

| Student | 35 | 8.1 |

| Pensioner | 20 | 4.6 |

| Grant recipient | 8 | 1.8 |

| Minors | 6 | 1.4 |

| Type of TB | ||

| PTB | 446 | 97.8 |

| EPTB | 6 | 1.3 |

| NR | 4 | 0.9 |

| Type of resistance | ||

| Monoresistance | 207 | 45.4 |

| Polyresistance | 237 | 52.0 |

| NR | 12 | 2.6 |

| Type of drug resistance | ||

| RR | 205 | 45.0 |

| MDR | 194 | 42.5 |

| Pre-XDR | 23 | 5.0 |

| XDR | 17 | 3.7 |

| INH-R | 6 | 1.3 |

| NR | 11 | 2.4 |

| Previous drug history | ||

| New | 226 | 49.6 |

| PT1 | 178 | 39.0 |

| PT2 | 43 | 9.4 |

| UNK | 1 | 0.2 |

| NR | 8 | 1.75 |

| HIV status | ||

| Positive | 281 | 61.6 |

| Negative | 165 | 36.2 |

| NR | 10 | 2.2 |

| BMI status | ||

| Underweight (<18.5 BMI) | 58 | 25.9 |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9 BMI) | 107 | 48.0 |

| Overweight (25–29.9 BMI) | 39 | 17.5 |

| Obese (≥30 BMI) | 19 | 8.5 |

| DR-TB Type | Age Groups (Years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–18 | 19–35 | 36–50 | 51–65 | >66 | |

| RR | 15 | 85 | 67 | 24 | 14 |

| MDR | 12 | 84 | 62 | 31 | 5 |

| Pre-XDR | 3 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 1 |

| XDR | 2 | 11 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| INH-R | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hosu, M.C.; Faye, L.M.; Apalata, T. Predicting Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Coinfection, Using Supervised Machine Learning Algorithm. Pathogens 2024, 13, 923. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens13110923

Hosu MC, Faye LM, Apalata T. Predicting Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Coinfection, Using Supervised Machine Learning Algorithm. Pathogens. 2024; 13(11):923. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens13110923

Chicago/Turabian StyleHosu, Mojisola Clara, Lindiwe Modest Faye, and Teke Apalata. 2024. "Predicting Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Coinfection, Using Supervised Machine Learning Algorithm" Pathogens 13, no. 11: 923. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens13110923

APA StyleHosu, M. C., Faye, L. M., & Apalata, T. (2024). Predicting Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Coinfection, Using Supervised Machine Learning Algorithm. Pathogens, 13(11), 923. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens13110923