Pathogenicity of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A/H5Nx Viruses in Avian and Murine Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Virus Strains

2.2. Animal Studies

2.2.1. Chickens Experimental Design

2.2.2. Mouse Experimental Design

2.2.3. Sample Size Calculation

2.2.4. Randomization and Control of Confounders

2.2.5. Blinding Procedures

2.3. Histopathological Examination

2.4. Viral Titration

2.5. Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Pathogenicity of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A/H5Nx Viruses in Avian Species

3.1.1. Morbidity and Mortality Rate of Chickens

3.1.2. Shedding and Replication Kinetics

3.1.3. Histopathological Findings in Chickens

3.2. Pathogenicity of HPAI- H5 Viruses in Mice

3.2.1. Pathogenicity in Mice

Clinical Signs and Mortality Rates

Viral Replication in Mice Organs

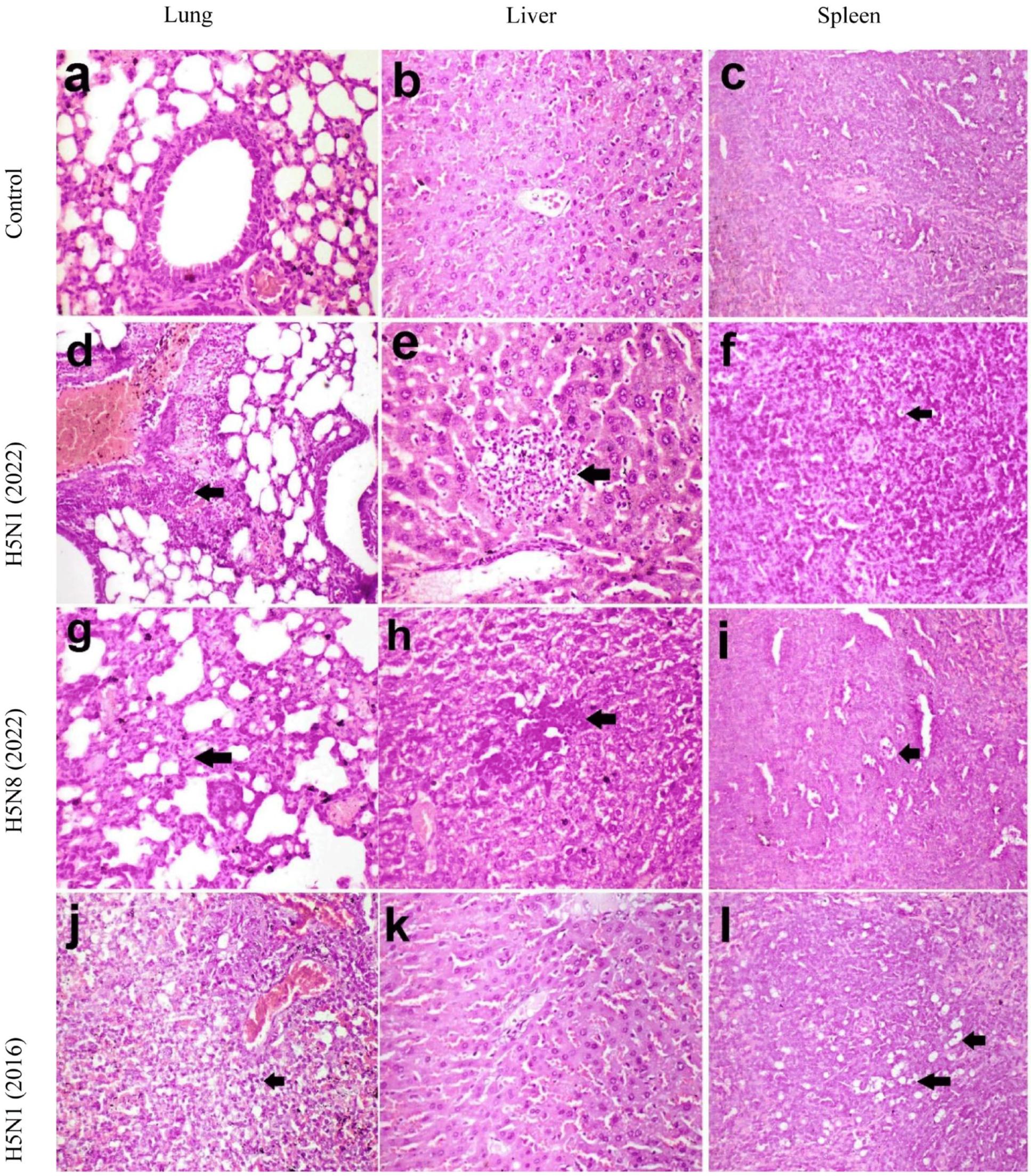

Histopathological Findings in Mice

3.3. Correlation Between Viral Loads and Disease Severity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Food Safety Authority; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; European Union Reference Laboratory for Avian Influenza; Fusaro, A.; Gonzales, J.L.; Kuiken, T.; Mirinavičiūtė, G.; Niqueux, É.; Ståhl, K.; Staubach, C.; et al. Avian influenza overview December 2023–March 2024. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e8754. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Qu, N.; Guo, Y.; Cao, L.; Wu, S.; Mei, K.; Sun, H.; Lu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Jiao, P. Phylogeny, pathogenicity, and transmission of H5N1 avian influenza viruses in chickens. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Sun, L.; Li, J.; Wu, Q.; Rezaei, N.; Jiang, S.; Pan, C. Potential cross-species transmission of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5 subtype (HPAI H5) viruses to humans calls for the development of H5-specific and universal influenza vaccines. Cell Discov. 2023, 9, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meseko, C.; Milani, A.; Inuwa, B.; Chinyere, C.; Shittu, I.; Ahmed, J.; Giussani, E.; Palumbo, E.; Zecchin, B.; Bonfante, F. The Evolution of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A (H5) in Poultry in Nigeria, 2021–2022. Viruses 2023, 15, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, K.E.; El-Kady, M.F.; EL-Sawah, A.A.; Luttermann, C.; Parvin, R.; Shany, S.; Beer, M.; Harder, T. Respiratory disease due to mixed viral infections in poultry flocks in Egypt between 2017 and 2018: Upsurge of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus subtype H5N8 since 2018. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salaheldin, A.H.; Kasbohm, E.; El-Naggar, H.; Ulrich, R.; Scheibner, D.; Gischke, M.; Hassan, M.K.; Arafa, A.-S.A.; Hassan, W.M.; Abd El-Hamid, H.S. Potential biological and climatic factors that influence the incidence and persistence of highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza virus in Egypt. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehia, N.; Naguib, M.M.; Li, R.; Hagag, N.; El-Husseiny, M.; Mosaad, Z.; Nour, A.; Rabea, N.; Hasan, W.M.; Hassan, M.K. Multiple introductions of reassorted highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses (H5N8) clade 2.3. 4.4 b causing outbreaks in wild birds and poultry in Egypt. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018, 58, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shesheny, R.; Moatasim, Y.; Mahmoud, S.H.; Song, Y.; El Taweel, A.; Gomaa, M.; Kamel, M.N.; Sayes, M.E.; Kandeil, A.; Lam, T.T. Highly pathogenic avian influenza a (H5N1) virus clade 2.3. 4.4 b in wild birds and live bird markets, Egypt. Pathogens 2023, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anis, A.; AboElkhair, M.; Ibrahim, M. Characterization of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N8 virus from Egyptian domestic waterfowl in 2017. Avian Pathol. 2018, 47, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; European Union Reference Laboratory for Avian Influenza; Adlhoch, C.; Fusaro, A.; Gonzales, J.L.; Kuiken, T.; Marangon, S.; Niqueux, É.; Staubach, C.; et al. Avian influenza overview June–September 2022. EFSA J. 2022, 20, e07597. [Google Scholar]

- Engelsma, M.; Heutink, R.; Harders, F.; Germeraad, E.A.; Beerens, N. Multiple introductions of reassorted highly pathogenic avian influenza H5Nx viruses clade 2.3. 4.4 b causing outbreaks in wild birds and poultry in The Netherlands, 2020–2021. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e02499-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakeer, A.M.; Khattab, M.S.; Aly, M.M.; Arafa, A.-S.; Amer, F.; Hafez, H.M.; Afify, M.M. Estimation of Pathological and Molecular Findings in Vaccinated and Non-Vaccinated Chickens Challenged with Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 Virus. Pak. Vet. J. 2019, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, E.L.; Meier, P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1958, 53, 457–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y. Biostatistics 102: Quantitative data–parametric & non-parametric tests. Blood Press 2003, 140, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; He, B.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Wu, W.; Yin, X.; Fan, B.; Fan, X.; Wang, J. Real-time RT-PCR for H5N1 avian influenza A virus detection. J. Med. Microbiol. 2007, 56, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-H.; Criado, M.F.; Swayne, D.E. Pathobiological origins and evolutionary history of highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2021, 11, a038679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohaim, M.A.; El Naggar, R.F.; Madbouly, Y.; AbdelSabour, M.A.; Ahmed, K.A.; Munir, M. Comparative infectivity and transmissibility studies of wild-bird and chicken-origin highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses H5N8 in chickens. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 74, 101594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Feng, M.; Zhu, O.; Yang, F.; Yin, Y.; Yin, Y.; Chen, S.; Qin, T.; Peng, D.; Liu, X. H5N8 Subtype avian influenza virus isolated from migratory birds emerging in Eastern China possessed a high pathogenicity in mammals. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, 3325–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, Y.-G.; Lee, Y.-N.; Lee, D.-H.; Shin, J.-I.; Lee, J.-H.; Chung, D.H.; Lee, E.-K.; Heo, G.-B.; Sagong, M.; Kye, S.-J. Multiple reassortants of H5N8 clade 2.3. 4.4 b highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses detected in South Korea during the winter of 2020–2021. Viruses 2021, 13, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.H.; Bahl, J.; Swayne, D.E.; Lee, Y.N.; Lee, Y.J.; Song, C.S.; Lee, D.H. Domestic ducks play a major role in the maintenance and spread of H5N8 highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses in South Korea. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020, 67, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, T.T. Studies on the Control of Avian Influenza and Newcastle Disease. Ph.D. Thesis, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, X.; Hu, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Cheng, H.; Xu, Y.; Li, Q.; He, D.; Liu, X.; Wang, X. Reassortant H5N1 avian influenza viruses containing PA or NP gene from an H9N2 virus significantly increase the pathogenicity in mice. Vet. Microbiol. 2016, 192, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattoli, G.; Milani, A.; Temperton, N.; Zecchin, B.; Buratin, A.; Molesti, E.; Aly, M.M.; Arafa, A.; Capua, I. Antigenic drift in H5N1 avian influenza virus in poultry is driven by mutations in major antigenic sites of the hemagglutinin molecule analogous to those for human influenza virus. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 8718–8724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Nissen, J.N.; Krog, J.S.; Breum, S.Ø.; Trebbien, R.; Larsen, L.E.; Hjulsager, C.K. Novel clade 2.3. 4.4 b highly pathogenic avian influenza A H5N8 and H5N5 viruses in Denmark, 2020. Viruses 2021, 13, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lycett, S.J.; Duchatel, F.; Digard, P. A brief history of bird flu. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2019, 374, 20180257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisfeld, A.J.; Biswas, A.; Guan, L.; Gu, C.; Maemura, T.; Trifkovic, S.; Wang, T.; Babujee, L.; Dahn, R.; Halfmann, P.J. Pathogenicity and transmissibility of bovine H5N1 influenza virus. Nature 2024, 633, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.A.; Fonville, J.M.; Brown, A.E.; Burke, D.F.; Smith, D.L.; James, S.L.; Herfst, S.; Van Boheemen, S.; Linster, M.; Schrauwen, E.J. The potential for respiratory droplet–transmissible A/H5N1 influenza virus to evolve in a mammalian host. Science 2012, 336, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, J.H.; Herfst, S.; Fouchier, R.A. How a virus travels the world. Science 2015, 347, 616–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, L.J.; Muench, H. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. Statistics I. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 22.0.; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi, A.; Zahediasl, S. Normality tests for statistical analysis: A guide for non-statisticians. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 10, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.K. Understanding one-way ANOVA using conceptual figures. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2017, 70, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, P.E.; Najab, J. Mann-Whitney U Test. In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-0-470-47921-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moder, K. Alternatives to F-test in one way ANOVA in case of heterogeneity of variances (a simulation study). Psychol. Test Assess. Model. 2010, 52, 343. [Google Scholar]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, T.A.; Altman, D.G. Basic statistical reporting for articles published in biomedical journals: The “Statistical Analyses and Methods in the Published Literature” or the SAMPL Guidelines. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2020, 40, 1769–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramey, A.M.; Reeves, A.B. Ecology of influenza A viruses in wild birds and wetlands of Alaska. Avian Dis. 2020, 64, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, N.; Esaki, M.; Kojima, I.; Khalil, A.M.; Osuga, S.; Shahein, M.A.; Okuya, K.; Ozawa, M.; Alhatlani, B.Y. Phylogenetic Characterization of Novel Reassortant 2.3. 4.4 b H5N8 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Viruses Isolated from Domestic Ducks in Egypt During the Winter Season 2021–2022. Viruses 2024, 16, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takadate, Y.; Tsunekuni, R.; Kumagai, A.; Mine, J.; Kikutani, Y.; Sakuma, S.; Miyazawa, K.; Uchida, Y. Different infectivity and transmissibility of H5N8 and H5N1 high pathogenicity avian influenza viruses isolated from chickens in Japan in the 2021/2022 season. Viruses 2023, 15, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Ara, T.; Amin, E.; Islam, S.; Sayeed, M.A.; Shirin, T.; Hassan, M.M.; Klaassen, M.; Epstein, J.H. Epidemiology and evolutionary dynamics of high pathogenicity avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 in Bangladesh. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2023, 2023, 8499018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibner, D.; Salaheldin, A.H.; Bagato, O.; Zaeck, L.M.; Mostafa, A.; Blohm, U.; Müller, C.; Eweas, A.F.; Franzke, K.; Karger, A. Phenotypic effects of mutations observed in the neuraminidase of human origin H5N1 influenza A viruses. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seekings, A.H.; Warren, C.J.; Thomas, S.S.; Lean, F.Z.; Selden, D.; Mollett, B.C.; van Diemen, P.M.; Banyard, A.C.; Slomka, M.J. Different outcomes of chicken infection with UK-origin H5N1-2020 and H5N8-2020 high-pathogenicity avian influenza viruses (clade 2.3. 4.4 b). Viruses 2023, 15, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Zhu, S.; An, Z.; You, B.; Li, Z.; Yao, Y.; Nair, V.; Liao, M. Dissection of key factors correlating with H5N1 avian influenza virus driven inflammatory lung injury of chicken identified by single-cell analysis. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.-H.; Nam, J.-H.; Kim, C.-K.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, H.; An, B.M.; Lee, N.-J.; Jeong, H.; Lee, S.-Y.; Yeo, S.-G. Pathogenicity of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Viruses Isolated from Cats in Mice and Ferrets, South Korea, 2023. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taft, A.S.; Ozawa, M.; Fitch, A.; Depasse, J.V.; Halfmann, P.J.; Hill-Batorski, L.; Hatta, M.; Friedrich, T.C.; Lopes, T.J.; Maher, E.A. Identification of mammalian-adapting mutations in the polymerase complex of an avian H5N1 influenza virus. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salaheldin, A.H.; Veits, J.; Abd El-Hamid, H.S.; Harder, T.C.; Devrishov, D.; Mettenleiter, T.C.; Hafez, H.M.; Abdelwhab, E.M. Isolation and genetic characterization of a novel 2.2. 1.2 a H5N1 virus from a vaccinated meat-turkeys flock in Egypt. Virol. J. 2017, 14, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chothe, S.K.; Srinivas, S.; Misra, S.; Nallipogu, N.C.; Gilbride, E.; LaBella, L.; Mukherjee, S.; Gauthier, C.H.; Pecoraro, H.L.; Webb, B.T. Marked neurotropism and potential adaptation of H5N1 Clade 2.3. 4.4. b virus in naturally infected domestic cats. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 14, 2440498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulit-Penaloza, J.A.; Brock, N.; Belser, J.A.; Sun, X.; Pappas, C.; Kieran, T.J.; Basu Thakur, P.; Zeng, H.; Cui, D.; Frederick, J. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) virus of clade 2.3. 4.4 b isolated from a human case in Chile causes fatal disease and transmits between co-housed ferrets. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2332667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsmo, E.J.; Wünschmann, A.; Beckmen, K.B.; Broughton-Neiswanger, L.E.; Buckles, E.L.; Ellis, J.; Fitzgerald, S.D.; Gerlach, R.; Hawkins, S.; Ip, H.S. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) virus clade 2.3. 4.4 b infections in wild terrestrial mammals, United States, 2022. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziosi, G.; Lupini, C.; Catelli, E.; Carnaccini, S. Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5 clade 2.3. 4.4 b virus infection in birds and mammals. Animals 2024, 14, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusaro, A.; Zecchin, B.; Giussani, E.; Palumbo, E.; Agüero-García, M.; Bachofen, C.; Bálint, Á.; Banihashem, F.; Banyard, A.C.; Beerens, N. High pathogenic avian influenza A (H5) viruses of clade 2.3. 4.4 b in Europe—Why trends of virus evolution are more difficult to predict. Virus Evol. 2024, 10, veae027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafa, A.-S.; Yamada, S.; Imai, M.; Watanabe, T.; Yamayoshi, S.; Iwatsuki-Horimoto, K.; Kiso, M.; Sakai-Tagawa, Y.; Ito, M.; Imamura, T. Risk assessment of recent Egyptian H5N1 influenza viruses. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, T.; Moncla, L.; Dudas, G.; VanInsberghe, D.; Sukhova, K.; Lloyd-Smith, J.O.; Worobey, M.; Lowen, A.C.; Nelson, M.I. The global H5N1 influenza panzootic in mammals. Nature 2025, 637, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Designation | Strain | Subtype | Clade | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H5N1/2016 | A/chicken/Egypt/S52/2016 | H5N1 | 2.2.1.2 | * RLVQCP |

| H5N1/2022 | A/chicken/Egypt/F71-F114C/2022 | H5N1 | 2.3.4.4b | Current surveillance |

| H5N8/2022 | A/chicken/Egypt/F71-S86C/2022 | H5N8 | 2.3.4.4b | Current surveillance |

| Groups | Doses | Viruses | 3 dpi | 4 dpi | 5 dpi | 6 dpi | 7 dpi | Mortality Rate% | Contact Transmission Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 106 | H5N1/2022 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 100% | |

| G1\ | contact | H5N1/2022 | 2 | 50% | |||||

| G2 | 106 | H5N8/2022 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 100% | |||

| G2\ | contact | H5N8/2022 | 2 | 50% | |||||

| G3 | 106 | H5N1/2016 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 100% | |||

| G3\ | contact | H5N1/2016 | 2 | 2 | 100% | ||||

| G4 | Neg. control | PBS | 0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mahmoud, S.H.; Khattab, M.S.; Yehia, N.; Zanaty, A.; Arafa, A.E.S.; Khalil, A.A. Pathogenicity of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A/H5Nx Viruses in Avian and Murine Models. Pathogens 2025, 14, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14020149

Mahmoud SH, Khattab MS, Yehia N, Zanaty A, Arafa AES, Khalil AA. Pathogenicity of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A/H5Nx Viruses in Avian and Murine Models. Pathogens. 2025; 14(2):149. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14020149

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahmoud, Sara H., Marwa S. Khattab, Nahed Yehia, Ali Zanaty, Abd El Sattar Arafa, and Ahmed A. Khalil. 2025. "Pathogenicity of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A/H5Nx Viruses in Avian and Murine Models" Pathogens 14, no. 2: 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14020149

APA StyleMahmoud, S. H., Khattab, M. S., Yehia, N., Zanaty, A., Arafa, A. E. S., & Khalil, A. A. (2025). Pathogenicity of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A/H5Nx Viruses in Avian and Murine Models. Pathogens, 14(2), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14020149