Empowering Women: Moving from Awareness to Action at the Immunology of Fungal Infections Gordon Research Conference

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Steps the GRC has Taken to Raise the Profile of Gender Issues

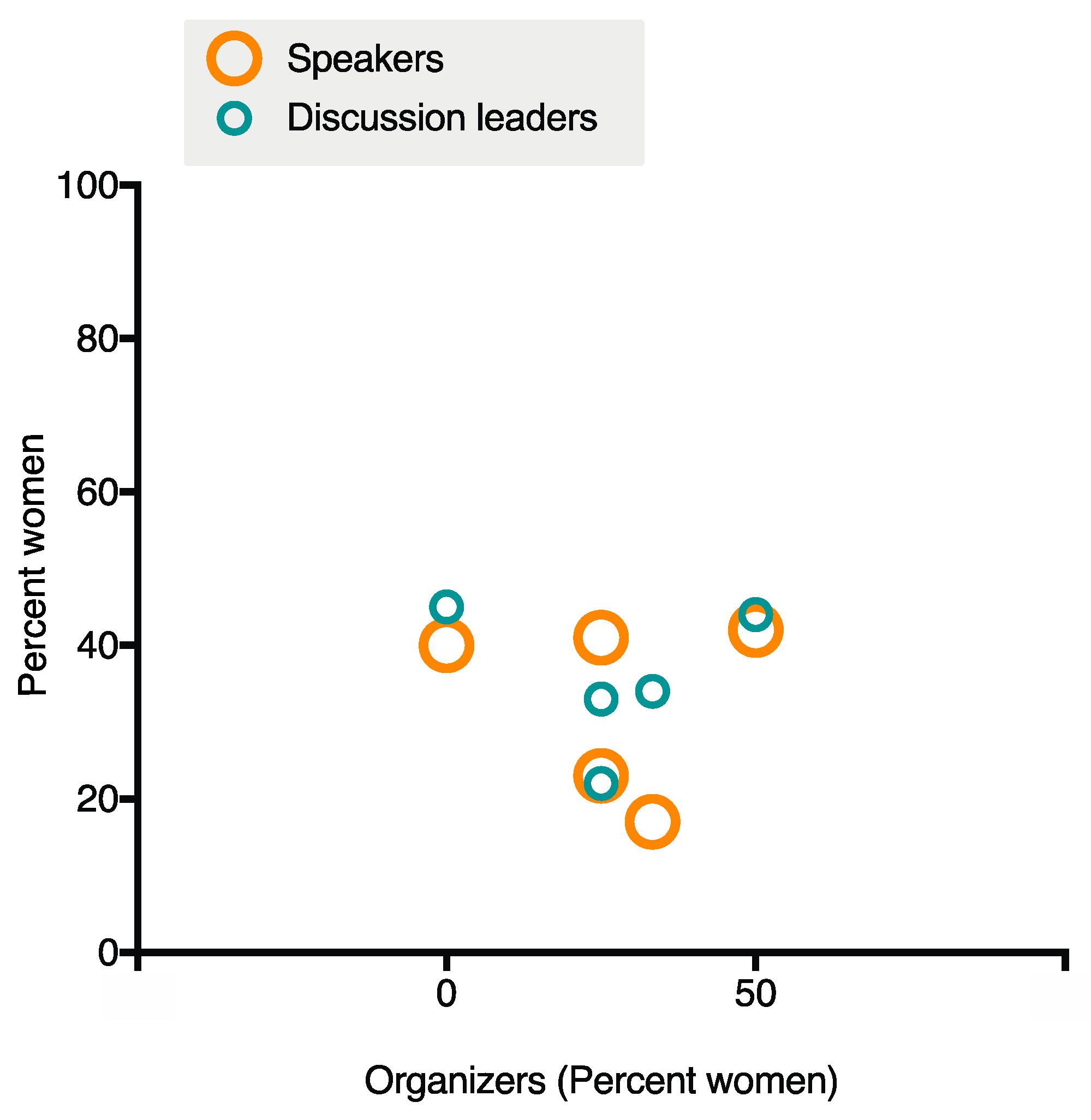

3. Gender Representation at the IFI over Time

4. Progress the Fungal Community has Made

- Identifying mentors and sponsors.

- Strategies for acting as an ally in cases of bias.

- Title IX and sexual harassment.

- Bias within academia (within the lab or within the department).

- Bias in the broader environment (administrators, reps, etc.).

- Bias encountered on the job market (interviews, negotiations, final offers).

- How do we recruit and retain under-represented groups to our field?

5. Our Experience with the Event

6. A Need for Strategies and Practical Solutions

- Mentors can take many forms. In general, mentors offer advice and guidance, but each mentor may be a source of support in a limited area. Identifying mentors with expertise in different areas will allow mentees to have high value conversations with the relevant mentor when an issue arises.

- Individuals should seek out mentors both within and outside their local institutes and at different career stages. Perspectives on common challenges can evolve over time or be dependent on particular local conditions. Identifying a range of perspectives can help avoid bias and potential conflicts of interest.

- In seeking out mentors, individuals should look for shared outlook and other commonalities, rather than focusing on traits such as gender.

- Mentorships can be formal (also known as coaching) or informal. For formal mentorships, mentees should identify specific goals to be discussed in scheduled one-on-one meetings and should be prepared to reflect on their own progress.

- Successful mentor-mentee relationships are characterized by open-ended questions that allow the mentee to identify blind spots or alternate solutions to common challenges, rather than providing out-of-the-box solutions.

- Peer mentorship can be a valuable resource both in terms of support and in terms of building trusted networks within cohorts.

- Sponsors are a distinct group of senior scientists that can act as champions, advocating on a junior researcher’s behalf. Sponsors may be less directly involved in advising, but can be influential in advocating for access to opportunities. The expectations of a sponsor, who is invested in your professional success, may be distinct from those of a mentor, who is invested in your personal success.

7. Suggested Actions for Individuals

- Engage with unconscious bias training to assess how you may be influenced by your own biases (https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/diversity/322996/lablearningonunconsciousbias.html).

- Seek out opportunities for networking and development, or professional coaching. For example, the National Postdoc Association offers courses and advice (https://www.nationalpostdoc.org/), the European Network of Postdoctoral Associations provides links to local Postdoc Associations (https://www.uc.pt/en/iii/postdoc/ENPA), and Nature Jobs offers guidance on identifying mentors and developing mentorship skills (https://www.nature.com/naturejobs/science/career_toolkit/mentoring)

- Identify yourself as a peer mentor or voice willingness to mentor junior researchers in particular areas.

- Identify yourself as an ally and actively advocate for women and other under-represented minorities. Some examples can be found in [37].

- Encourage junior researchers by modelling mentorship in local groups such as those held by UCSF’s Women in Life Sciences group [38].

- Add names to the Women Researchers in Fungi and Oomycetes spreadsheet [30].

- Establish or join a peer mentorship group at your local institute or online. There are several examples of these already, including NewPI_Slack and UK_NewPI twitter and slack channels that can be accessed online.

- Seek out opportunities for interacting with potential mentors at meetings or through local networks. Speak with peers or supervisors who may be able to help identify potential mentors.

8. Suggested Actions for Future GRCs

- Allow extended time in the schedule for the Power Hour, to enable more in-depth discussion. In the program structure, the Power Hour precedes a poster session, so junior researchers who are presenting in this session are disadvantaged.

- Hold a dedicated session prior to the main meeting to address various areas in career development specifically focused on women and under-represented minorities. This could integrate early career participants of the Gordon Research Symposium as well as attendees of the GRC proper. Possible topics identified by 2019 discussants include:

- How/when to say yes or no to new opportunities/chores.

- How to more effectively handle the situation when you are the one on the receiving end of the bias.

- How to be aware of and decrease our own biases.

- Ask attendees to hold Office Hours during the meeting, in the breaks or at meals, when they would self-identify as being willing to act as mentors one-on-one or to small groups to discuss specific issues. These could be led by established PIs, but could also be a chance for students and post-docs to identify as peer mentors. This strategy targets three goals: (1) identifying mentors and potential sponsors outside trainees’ institution; (2) identifying allies; and (3) developing leadership skills and confidence when facing problems themselves.

9. Suggested Actions for Future Power Hours

- Model difficult conversations surrounding a hypothetical but plausible case that could occur in a lab. Ask discussants to consider the problem from different points of view (PI, grad student, post doc, etc.).

- Consider how best to encourage conference attendees, particularly those who may be reluctant to engage, to join the Power Hour.

- Consider how to better use technology to share discussant perspectives. Word clouds and anonymous response submission systems can enable participation and perspective sharing from less vocal members.

- Consider how future Power Hours can take a wider view of challenges around gender and equality, particularly given the expanding understanding of the breadth of human gender identity. Power Hour conveners should consider specific challenges encountered by these groups including inability to access resources, bullying, and harassment.

- Consider how intersectionality with other characteristics (race, nationality, language, age, etc.) may impact attendee participation in the meeting and in career progression.

10. Suggested Actions for the Broader Microbiology Community

- At future conferences, consider running sessions addressing some of the identified challenges.

- Engage with efforts to collect information about gender and minority representation in STEM worldwide [8].

- Provide a forum for discussing the importance of diversity.

- Provide family friendly support (lactation rooms, child care subsidies, reduced fees for partners or support, travel grants for partners/caretakers).

- Consider gender balance at meetings, both at the organizational and speaker level. The Women Researchers in Fungi and Oomycetes database can serve as a resource [30].

- Continue to build on successes in promoting gender parity across invited and selected speakers and consider strategies for broadening participation in other ways (during question periods, at poster sessions, etc.). For example, research has shown that women tend to ask fewer questions at seminars, but a moderator who selects a woman to be first questioner can increase the number of women who participate subsequently [42].

- Expand strategies for raising the profiles of under-represented minority scientists beyond gender to other groups.

- Advocate at the institutional level for improved support and infrastructure for researchers taking leave related to caretaking and for those returning to work after a career break. Examples of initiatives in place include the Athena Swan Charter in the UK [43] and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Gender Inequality Task Force Report in the US [44].

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Confidentiality Statement

References

- AAMC. The State of Women in Academic Medicine: The Pipeline and Pathways to Leadership, 2015–2016; AAMC: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Okahana, H.; Zhou, E. 2016 CGS/GRE Survey of Graduate Enrollment and Degrees. Available online: https://cgsnet.org/2017-forums (accessed on 21 May 2019).

- U.S. Medical School Faculty Data. Available online: https://www.aamc.org/data/facultyroster/reports/ (accessed on 21 May 2019).

- Kamerlin, S.C. Where are the female science professors? A personal perspective. F1000Res 2016, 5, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Society of Biology. Women in Academic STEM Careers: A Contribution from the Society of Biology to the House of Commons Science and Technology Select Committee; Charles Darwin House: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics, U.I.F. Women are Missing from the Ranks of Higher Education and Research. Available online: http://uis.unesco.org/en/news/women-are-missing-ranks-higher-education-and-research (accessed on 17 May 2019).

- Nelson, D.J.; Brammer, C.N. A National Analysis of Minorities in Science and Engineering Faculties at Research Universities, 2nd ed.; University of Oklahoma: Norman, OK, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. STEM and Gender Advancement (SAGA): Improving Measurement and Policies for Gender Equality in STEM. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/priority-areas/gender-and-science/improving-measurement-of-gender-equality-in-stem/stem-and-gender-advancement-saga/ (accessed on 6 July 2019).

- Guglielmi, G. Gender bias goes away when grant reviewers focus on the science. Nature 2018, 554, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magua, W.; Zhu, X.; Bhattacharya, A.; Filut, A.; Potvien, A.; Leatherberry, R.; Lee, Y.G.; Jens, M.; Malikireddy, D.; Carnes, M.; et al. Are Female Applicants Disadvantaged in National Institutes of Health Peer Review? Combining Algorithmic Text Mining and Qualitative Methods to Detect Evaluative Differences in R01 Reviewers’ Critiques. J. Women’s Health 2017, 26, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clauset, A.; Arbesman, S.; Larremore, D.B. Systematic inequality and hierarchy in faculty hiring networks. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1400005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Highlights of women’s Earnings in 2017: Report 1075. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/womens-earnings/2017/home.htm (accessed on 15 May 2019).

- UNESCO. Women in Science; UNESCO Institute for Statistics: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Acton, S.E.; Bell, A.; Toseland, C.P.; Twelvetrees, A. The life of P.I. Transitions to Independence in Academia. BioRXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivie, R.; Tesfaye, C.L.; Czujko, R.; Chu, R. The Global Survey of Physicists: A Collaborative Effort Illuminates the Situation of Women in Physics. AIP Conf. Proc. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, N.H. Experience of Women at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, In Women in the Chemical Workforce: A Workshop Report to the Chemical Sciences Roundtable; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Casadevall, A. Achieving Speaker Gender Equity at the American Society for Microbiology General Meeting. MBio 2015, 6, e01146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiko, J.R.; Anderson, A.J.M.; Gordon, R.A. Representation of Women Among Academic Grand Rounds Speakers. J. AMA Intern Med. 2017, 177, 722–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadevall, A.; Handelsman, J. The presence of female conveners correlates with a higher proportion of female speakers at scientific symposia. MBio 2014, 5, e00846-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbell, L.A.; Young, T.P.; Harcourt, A.H. Stag parties linger: Continued gender bias in a female-rich scientific discipline. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, J.; Dugdale, H.L.; Radersma, R.; Hinsch, M.; Buehler, D.M.; Saul, J.; Porter, L.; Liker, A.; De Cauwer, I.; Johnson, P.J.; et al. Fewer invited talks by women in evolutionary biology symposia. J. Evol. Biol. 2013, 26, 2063–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pell, A.N. Fixing the leaky pipeline: Women scientists in academia. J. Anim. Sci. 1996, 74, 2843–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, R.S.; Voskuhl, R.; Segal, B.M.; Dittel, B.N.; Lane, T.E.; Bethea, J.R.; Carson, M.J.; Colton, C.; Rosi, S.; Anderson, A.; et al. Speaking out about gender imbalance in invited speakers improves diversity. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, R.S.; Voskuhl, R.; Segal, B.M.; Dittel, B.N.; Lane, T.E.; Bethea, J.R.; Carson, M.J.; Colton, C.; Rosi, S.; Anderson, A.; et al. Speaking Out about Gender Imbalance in Invited Speakers Improves Diversity. Available online: https://f1000.com/prime/727549587 (accessed on 21 May 2019).

- West, J.D.; Jacquet, J.; King, M.M.; Correll, S.J.; Bergstrom, C.T. The role of gender in scholarly authorship. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broderick, N.A.; Casadevall, A. Gender inequalities among authors who contributed equally. Elife 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpern, D.F.; Benbow, C.P.; Geary, D.C.; Gur, R.C.; Hyde, J.S.; Gernsbacher, M.A. Sex, Math and Scientific Achievement: Why do men dominate the fields of science, engineering and mathematics? Sci. Am. Mind 2007, 18, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The GRC Power Hour. Available online: https://www.grc.org/the-power-hour/ (accessed on 21 May 2019).

- Immunology of Fungal Infections. Available online: https://www.grc.org/immunology-of-fungal-infections-conference (accessed on 21 May 2019).

- Momany, M.; Jason, S. Women Researchers in Fungi & Oomycetes. Available online: http://fungalgenomes.org/blog/wrifo/ (accessed on 18 May 2019).

- Riquelme, M.; Aime, M.C.; Branco, S.; Brand, A.; Brown, A.; Glass, N.L.; Kahmann, R.; Momany, M.; Rokas, A.; Trail, F. The power of discussion: Support for women at the fungal Gordon Research Conference. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2018, 121, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmader, T.; Whitehead, J.; Wysocki, V.H. A Linguistic Comparison of Letters of Recommendation for Male and Female Chemistry and Biochemistry Job Applicants. Sex Roles 2007, 57, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trix, F.; Psenka, C. Exploring the color of glass: Letters of recommendation for female and male medical faculty. Discourse Soc. 2003, 14, 191–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrentine, F.E.; Dreisbach, C.N.; St Ivany, A.R.; Hanks, J.B.; Schroen, A.T. Influence of Gender on Surgical Residency Applicants’ Recommendation Letters. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2019, 228, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, M.J.; Bristol, M.B.; Atherton, P.H.; Schwab, C.W.; Sonnad, S.S. Improving the recruitment and hiring process for women faculty. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2008, 206, 1210–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cech, E.A.; Blair-Loy, M. The changing career trajectories of new parents in STEM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powel, K. How some men are challenging gender inequity in the lab. Nature Magazine, 27 February 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, N. Let’s Talk: Small-Group Mentoring Dinners. Science Magazine, 3 May 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hund, A.K.; Churchill, A.C.; Faist, A.M.; Havrilla, C.A.; Love Stowell, S.M.; McCreery, H.F.; Ng, J.; Pinzone, C.A.; Scordato, E.S.C. Transforming mentorship in STEM by training scientists to be better leaders. Ecol. Evolut. 2018, 8, 9962–9974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chopra, V.; Vaughn, V.; Saint, S. The Mentoring Guide: Helping Mentors and Mentees Succeed; Michigan Publishing: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.J.; Fonseca, A.; Ramos, M.M.; Costa, M.; Kilteni, K.; Andersen, L.M.; Harber-Aschan, L.; Moscoso, J.A.; Bagchi, S. Associations, E.N.P.A. Postdoc X-ray in Europe 2017 Work conditions, productivity, institutional support and career outlooks. bioRxiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, A.J.; Croft, A.; Lukas, D.; Sandstrom, G.M. Women’s visibility in academic seminars: Women ask fewer questions than men. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HE, A. Advance HE’s Athena SWAN Charter. Available online: https://www.ecu.ac.uk/equality-charters/athena-swan/ (accessed on 18 May 2019).

- NIH Intramural Research Program Task Force. Addressing Gender Inequality in the NIH Intramural Research Program Action Task Force Report and Recommendations; Diversity, N.S.W.: Rocks, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ballou, E.R.; Gaffen, S.L.; Gow, N.A.R.; Hise, A.G. Empowering Women: Moving from Awareness to Action at the Immunology of Fungal Infections Gordon Research Conference. Pathogens 2019, 8, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens8030103

Ballou ER, Gaffen SL, Gow NAR, Hise AG. Empowering Women: Moving from Awareness to Action at the Immunology of Fungal Infections Gordon Research Conference. Pathogens. 2019; 8(3):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens8030103

Chicago/Turabian StyleBallou, Elizabeth R., Sarah L. Gaffen, Neil A. R. Gow, and Amy G. Hise. 2019. "Empowering Women: Moving from Awareness to Action at the Immunology of Fungal Infections Gordon Research Conference" Pathogens 8, no. 3: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens8030103

APA StyleBallou, E. R., Gaffen, S. L., Gow, N. A. R., & Hise, A. G. (2019). Empowering Women: Moving from Awareness to Action at the Immunology of Fungal Infections Gordon Research Conference. Pathogens, 8(3), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens8030103