MicroRNA-210 Regulates Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Apoptosis in Porcine Embryos

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Ethics and Chemicals

2.2. Retrieval of Oocyte and In Vitro Maturation (IVM)

2.3. Electrical Activation of Porcine Oocytes

2.4. Microinjection of Porcine Oocytes

2.5. Embryo Development and Total Cells Blastocyst Number after Activation

2.6. The X-Box Binding Protein 1 (XBP1) Immunofluorescence Staining in Blastocyst

2.7. Analysis of Gene Expression in Blastocysts by Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

2.8. Research Outline

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of miR-210 (Inhibitor and Mimic) Injection on Cleavage, Blastocyst Rate, and Total Blastocyst Cell Number

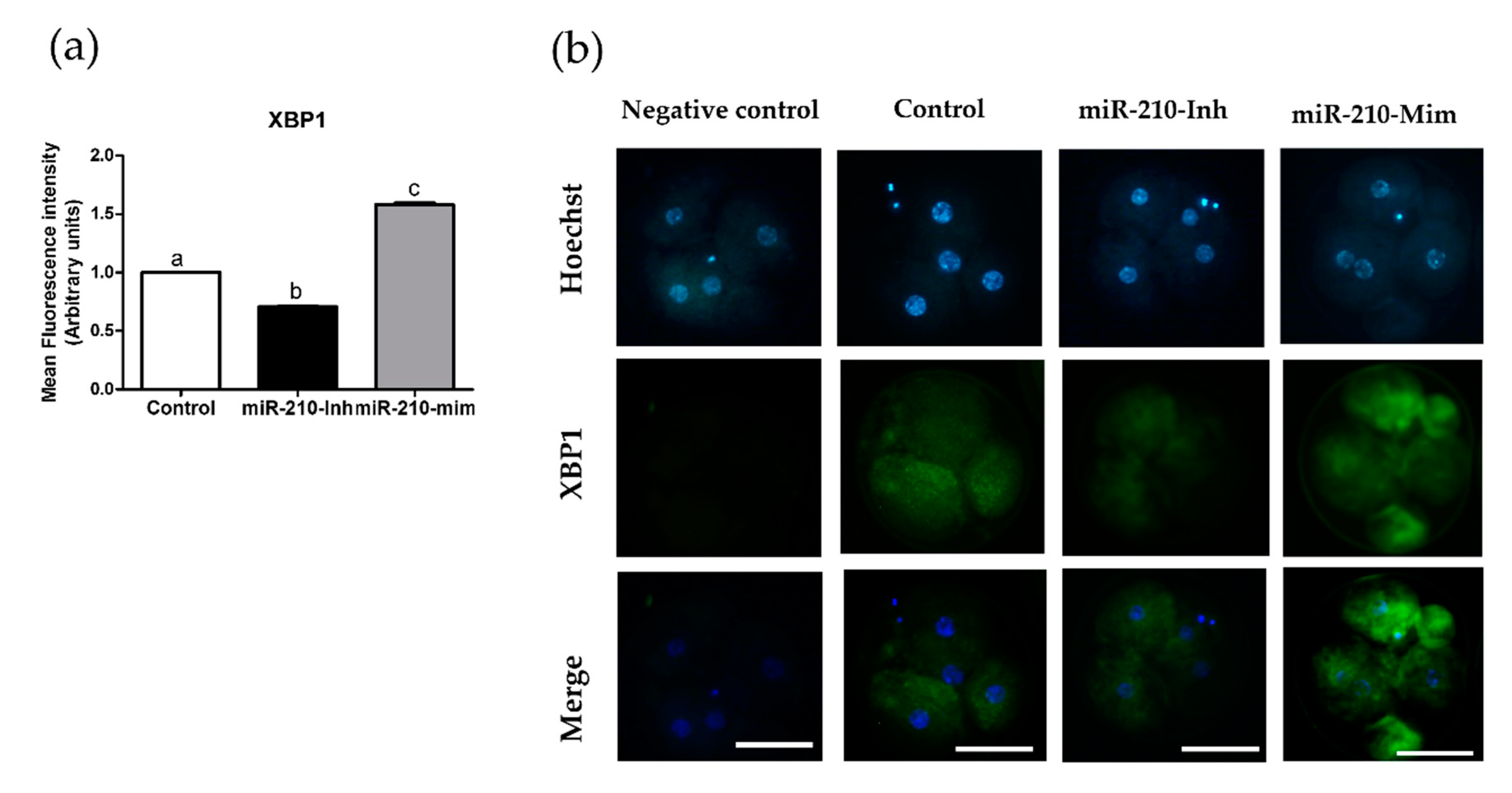

3.2. Expression Levels of XBP1 in Embryos after Microinjection of miR-210 (Inhibitor and Mimic)

3.3. Effects of miR-210 (Inhibitor and Mimic) Treatment on Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Related Genes, Caspase 3, NANOG, and SOX 2 in Blastocysts

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hausser, J.; Syed, A.P.; Bilen, B.; Zavolan, M. Analysis of CDS-located miRNA target sites suggests that they can effectively inhibit translation. Genome Res. 2013, 23, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, T.M. Illuminating the silence: Understanding the structure and function of small RNAs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, C.; Yao, J.; Cao, C.; Liang, X.; Huang, J.; Han, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, G.; Tao, C.; Li, C.; et al. PPARgamma is regulated by miR-27b-3p negatively and plays an important role in porcine oocyte maturation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 479, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stowe, H.M.; Curry, E.; Calcatera, S.M.; Krisher, R.L.; Paczkowski, M.; Pratt, S. Cloning and expression of porcine Dicer and the impact of developmental stage and culture conditions on MicroRNA expression in porcine embryos. Gene 2012, 501, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bick, J.T.; Flöter, V.L.; Robinson, M.D.; Bauersachs, S.; Ulbrich, S.E. Small RNA-seq analysis of single porcine blastocysts revealed that maternal estradiol-17beta exposure does not affect miRNA isoform (isomiR) expression. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, L.-A.; Murphy, P.R. MicroRNA: Biogenesis, Function and Role in Cancer. Curr. Genom. 2010, 11, 537–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, A. RNA editing enters the limelight in cancer. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 130–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannion, N.; Arieti, F.; Gallo, A.; Keegan, L.P.; O’Connell, M.A. New Insights into the Biological Role of Mammalian ADARs; the RNA Editing Proteins. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 2338–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, T.-Y. MicroRNAs in Human Diseases: From Cancer to Cardiovascular Disease. Immune Netw. 2011, 11, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, T.-Y. MicroRNAs in Human Diseases: From Lung, Liver and Kidney Diseases to Infectious Disease, Sickle Cell Disease and Endometrium Disease. Immune Netw. 2011, 11, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, T.-Y. MicroRNAs in Human Diseases: From Autoimmune Diseases to Skin, Psychiatric and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Immune Netw. 2011, 11, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasanaro, P.; D’Alessandra, Y.; Di Stefano, V.; Melchionna, R.; Romani, S.; Pompilio, G.; Capogrossi, M.C.; Martelli, F. MicroRNA-210 Modulates Endothelial Cell Response to Hypoxia and Inhibits the Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Ligand Ephrin-A3. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 15878–15883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoji, T.; Nakasa, T.; Yamasaki, K.; Kodama, A.; Miyaki, S.; Niimoto, T.; Okuhara, A.; Kamei, N.; Adachi, N.; Ochi, M. The Effect of Intra-articular Injection of MicroRNA-210 on Ligament Healing in a Rat Model. Am. J. Sports Med. 2012, 40, 2470–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavelloni, A.; Ramazzotti, G.; Poli, A.; Piazzi, M.; Focaccia, E.; Blalock, W.; Faenza, I. MiRNA-210: A Current Overview. Anticancer. Res. 2017, 37, 6511–6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voloboueva, L.A.; Sun, X.; Xu, L.; Ouyang, Y.B.; Giffard, R.G. Distinct Effects of miR-210 Reduction on Neurogenesis: Increased Neuronal Survival of Inflammation But Re-duced Proliferation Associated with Mitochondrial Enhancement. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 3072–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, C.; Tang, X. Downregulation of microRNA-210 inhibits osteosarcoma growth in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 3674–3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Dasgupta, C.; Li, Y.; Bajwa, N.M.; Xiong, F.; Harding, B.; Hartman, R.; Zhang, L. Inhibition of microRNA-210 provides neuroprotection in hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in neonatal rats. Neurobiol. Dis. 2016, 89, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, M.; Zheng, M.; Hayashi, M.; Lee, J.D.; Yoshino, O.; Lin, S.; Han, J. Impaired microRNA processing causes corpus luteum insufficiency and infertility in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 1944–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Niu, Z.; Li, Q.; Pang, R.T.; Chiu, P.C.; Yeung, W. MicroRNA and Embryo Implantation. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2015, 75, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, N.; Baehner, L.; Moltzahn, F.; Melton, C.; Shenoy, A.; Chen, J.; Blelloch, R. MicroRNA Function Is Globally Suppressed in Mouse Oocytes and Early Embryos. Curr. Biol. 2010, 20, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; de Sousa Lopes, S.M.C.; Kaneda, M.; Tang, F.; Hajkova, P.; Lao, K.; O’Carroll, D.; Das, P.P.; Tarakhovsky, A.; Miska, E.A.; et al. MicroRNA Biogenesis Is Required for Mouse Primordial Germ Cell Development and Spermatogenesis. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.S.; Blelloch, R. Small RNAs in Germline Development; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 102, pp. 159–205. [Google Scholar]

- Reza, A.M.M.T.; Choi, Y.-J.; Han, S.G.; Song, H.; Park, C.; Hong, K.; Kim, J.-H. Roles of microRNAs in mammalian reproduction: From the commitment of germ cells to peri-implantation embryos. Biol. Rev. 2019, 94, 415–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.C.; Saadeldin, I.M.; Oh, H.J. Embryonic–maternal cross-talk via exosomes: Potential implications. Stem Cells Cloning Adv. Appl. 2015, 8, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, F.; Kaneda, M.; O’Carroll, D.; Hajkova, P.; Barton, S.C.; Sun, Y.A.; Lee, C.; Tarakhovsky, A.; Lao, K.; Surani, M.A. Maternal microRNAs are essential for mouse zygotic development. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svoboda, P.; Flemr, M. The role of miRNAs and endogenous siRNAs in maternal-to-zygotic reprogramming and the establishment of pluripotency. EMBO Rep. 2010, 11, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesfaye, D.; Worku, D.; Rings, F.; Phatsara, C.; Tholen, E.; Schellander, K.; Hoelker, M. Identification and expression profiling of microRNAs during bovine oocyte maturation using heterologous approach. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2009, 76, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muralimanoharan, S.; Maloyan, A.; Mele, J.; Guo, C.; Myatt, L.G. MIR-210 modulates mitochondrial respiration in placenta with preeclampsia. Placenta 2012, 33, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, S.Y.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Hemann, C.; Mahoney, C.E.; Zweier, J.L.; Loscalzo, J. MicroRNA-210 controls mitochondrial metabolism during hypoxia by repressing the iron-sulfur cluster assembly pro-teins ISCU1/2. Cell Metab. 2009, 10, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, P.; Luthra, R. Hypoxia-regulated microRNA-210 modulates mitochondrial function and decreases ISCU and COX10 expression. Oncogene 2010, 29, 4362–4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagscherer, K.E.; Fassl, A.; Sinkovic, T.; Richter, J.; Schecher, S.; Macher-Goeppinger, S.; Roth, W. MicroRNA-210 induces apoptosis in colorectal cancer via induction of reactive oxygen. Cancer Cell Int. 2016, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Sun, S.; Zhang, X.Q.; De Zhang, P.; Ho, A.S.; Kiang, K.M.; Fung, C.F.; Lui, W.M.; Leung, G.K.K. MicroRNA-210 and Endoplasmic Reticulum Chaperones in the Regulation of Chemoresistance in Glioblastoma. J. Cancer 2015, 6, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Meara, C.M.; Murray, J.D.; Mamo, S.; Gallagher, E.; Roche, J.; Lonergan, P. Gene silencing in bovine zygotes: siRNA transfection versus microinjection. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2011, 23, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, M.; Kosuke, M.; Koriyama, M.; Inada, E.; Saitoh, I.; Ohtsuka, M.; Nakamura, S.; Sakurai, T.; Watanabe, S.; Miyoshi, K. Timing of CRISPR/Cas9-related mRNA microinjection after activation as an important factor affecting genome editing effi-ciency in porcine oocytes. Theriogenology 2018, 108, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Ma, X.; An, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, Z. MicroRNA-29b regulates DNA methylation by targeting Dnmt3a/3b and Tet1/2/3 in porcine early embryo development. Dev. Growth Differ. 2018, 60, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanihara, F.; Hirata, M.; Nguyen, N.T.; Le, Q.A.; Hirano, T.; Otoi, T. Effects of concentration of CRISPR/Cas9 components on genetic mosaicism in cytoplasmic microinjected porcine embry-os. J. Reprod. Dev. 2019, 65, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.-X.; Lee, S.; Taweechaipaisankul, A.; Kim, G.A.; Lee, B.C. The HDAC Inhibitor LAQ824 Enhances Epigenetic Reprogramming and In Vitro Development of Porcine SCNT Embryos. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 41, 1255–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuziwara, C.S.; Kimura, E.T. Insights into Regulation of the miR-17-92 Cluster of miRNAs in Cancer. Front. Med. 2015, 2, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayder, H.; O’Brien, J.; Nadeem, U.; Peng, C. MicroRNAs: Crucial regulators of placental development. Reproduction 2018, 155, R259–R271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.C.; Feinbaum, R.L.; Ambros, V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 1993, 75, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behm-Ansmant, I.; Rehwinkel, J.; Doerks, T.; Stark, A.; Bork, P.; Izaurralde, E. mRNA degradation by miRNAs and GW182 requires both CCR4:NOT deadenylase and DCP1:DCP2 decapping complexes. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 1885–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Yao, H.; Li, C.; Pu, M.; Yao, X.; Yang, H.; Qi, X.; Ren, J.; Wang, Y. A dual inhibition: microRNA-552 suppresses both transcription and translation of cytochrome P450 2E1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Bioenerg. 2016, 1859, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalanotto, C.; Cogoni, C.; Zardo, G. MicroRNA in Control of Gene Expression: An Overview of Nuclear Functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Ma, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, L. Inhibition of microRNA-210 suppresses pro-inflammatory response and reduces acute brain injury of ischemic stroke in mice. Exp. Neurol. 2018, 300, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Z.; Huang, H.; Sun, F. The functional and predictive roles of miR-210 in cryptorchidism. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, srep32265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Zeng, J.; Yuan, J.; Deng, X.; Huang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, P.; Feng, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; et al. MicroRNA-210 overexpression promotes psoriasis-like inflammation by inducing Th1 and Th17 cell differentiation. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 2551–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latham, K.E. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Signaling in Mammalian Oocytes and Embryos: Life in Balance. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2015, 316, 227–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, M.; Gardner, D.K. Understanding cellular disruptions during early embryo development that perturb viability and fetal development. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2005, 17, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Lee, J.E.; Kang, J.W.; Shin, H.Y.; Lee, J.B.; Jin, D.I. Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Stress and Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) in Mammalian Oocyte Maturation and Preim-plantation Embryo Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Diao, Y.F.; Oqani, R.K.; Han, R.X.; Jin, D.I. Effect of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress on Porcine Oocyte Maturation and Parthenogenetic Embryonic Development In Vitro. Biol. Reprod. 2012, 86, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridlo, M.R.; Kim, G.A.; Taweechaipaisankul, A.; Kim, E.H.; Lee, B.C. Zinc supplementation alleviates endoplasmic reticulum stress during porcine oocyte in vitro maturation by upregulating zinc transporters. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, T.; Pin, C.L.; Watson, A.J. Embryo collection induces transient activation of XBP1 arm of the ER stress response while em-bryo vitrification does not. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 18, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, C.J.; Kopp, M.C.; Larburu, N.; Nowak, P.R.; Ali, M.M.U. Structure and Molecular Mechanism of ER Stress Signaling by the Unfolded Protein Response Signal Activator IRE1. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2019, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadj-Moussa, H.; Storey, K.B. The OxymiR response to oxygen limitation: A comparative microRNA perspective. J. Exp. Biol. 2020, 223, jeb204594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Ding, L.; Bennewith, K.L.; Tong, R.T.; Welford, S.M.; Ang, K.K.; Story, M.; Le, Q.-T.; Giaccia, A.J. Hypoxia-Inducible mir-210 Regulates Normoxic Gene Expression Involved in Tumor Initiation. Mol. Cell 2009, 35, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, M.; Lee, A.S. ER chaperones in mammalian development and human diseases. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 3641–3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalak, M.; Gye, M.C. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in periimplantation embryos. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 2015, 42, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, M.; Kaufman, R.J. ER stress and the unfolded protein response. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2005, 569, 29–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Li, M.; Mao, C.; Lee, A.S. Endoplasmic reticulum stress triggers an acute proteasome-dependent degradation of ATF6. J. Cell. Biochem. 2004, 92, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-H.; Aydemir, T.B.; Kim, J.; Cousins, R.J. Hepatic ZIP14-mediated zinc transport is required for adaptation to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E5805–E5814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q.-C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.-Q.; Wang, Y.-H.; An, C.-Q.; Yang, K.-Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. TMCO1 is essential for ovarian follicle development by regulating ER Ca2+ store of granulosa cells. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 1686–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, S. Intracellular calcium oscillations in mammalian eggs at fertilization. J. Physiol. 2007, 584, 713–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takehara, I.; Igarashi, H.; Kawagoe, J.; Matsuo, K.; Takahashi, K.; Nishi, M.; Nagase, S. Impact of endoplasmic reticulum stress on oocyte aging mechanisms. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 26, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Lian, S.; Zhen, L.; Zang, S.; Chen, Y.; Lang, L.; Xu, B.; Guo, J.; Ji, H.; Wu, R.; et al. The Favored Mechanism for Coping with Acute Cold Stress: Upregulation of miR-210 in Rats. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 46, 2090–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Wu, J.; Xu, N.; Xie, W.; Li, M.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, B.B.; Zhang, Y. MiR-210 disturbs mitotic progression through regulating a group of mitosis-related genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caplen, N.J.; Parrish, S.; Imani, F.; Fire, A.; Morgan, R.A. Specific inhibition of gene expression by small double-stranded RNAs in invertebrate and vertebrate systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 9742–9747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persengiev, S.P.; Zhu, X.; Green, M.R. Nonspecific, concentration-dependent stimulation and repression of mammalian gene expression by small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). Struct. 30S Ribosomal Decod. Complex Ambient Temp. 2004, 10, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barik, S. Silence of the transcripts: RNA interference in medicine. J. Mol. Med. 2005, 83, 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Product Number | Micro-RNA | Sequences (5′-3′) | Base Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| oligo-rna-single-customorder | cfa-miR-210 inhibitor | UCAGCCGCUGUCACACGCACAGU | 23 |

| oligo-rna-double-customorder | cfa-miR-210 mimic | S-ACUGUGCGUGUGACAGCGGCUGA AS-UCAGCCGCUGUCACACGCACAGU | 21 |

| Genes | Primer Sequences (5′-3′) | Product Size (bp) | Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | F: GTCGGTTGTGGATCTGACCT R: TTGACGAAGTGGTCGTTGAG | 207 | NM_001206359 |

| ATF4 | F: AGTCCTTTTCTGCGAGTGGG R: CTGCTGCCTCTAATACGCCA | 80 | NM_001123078.1 |

| PTPN1/ PTP1B | F: GGTGCTCACGACTCTTCCTC R: TTCTCTGCACGAGCTTCTGA | 158 | NM_001113435.1 |

| uXBP1 | F: CATGGATTCTGACGGTGTTG R: GTCTGGGGAAGGACATCTGA | 106 | NM_001142836.1 |

| sXBP1 | F: GGAGTTAAGACAGCGCTTGG R: GAGATGTTCTGGAGGGGTGA | 142 | NM_001271738.1 |

| Caspase 3 | F: GCCATGGTGAAGAAGGAAAA R: GGCAGGCCTGAATTATGAAA | 132 | NM_214131.1 |

| NANOG | F: GGTTTATGGGCCTGAAGAAA R: GATCCATGGAGGAAGGAAGA | 98 | NM_001129971 |

| SOX2 | F: ATGCACAACTCGGAGATCAG R: TATAATCCGGGTGCTCCTTC | 130 | NM_001123197 |

| Treatment | Number of Embryos Cultured | No. of Embryos Developed to (Mean ± SEM, %) | TCN (Mean ± SEM) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥2 cells | Blastocyst | |||

| Control | 223 | 193 (86.61 ± 0.52) a | 46 (20.61 ± 0.57) a | 65.58 ± 0.95 a |

| miR-210-inhibitor | 225 | 212 (90.25 ± 0.5) b | 79 (33.19 ± 2.37) b | 76.25 ± 1.11 b |

| miR-210-mimic | 235 | 165 (73.28 ± 1.4) c | 33 (14.6 ± 0.46) c | 49.33 ± 0.76 c |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ridlo, M.R.; Kim, E.H.; Kim, G.A. MicroRNA-210 Regulates Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Apoptosis in Porcine Embryos. Animals 2021, 11, 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11010221

Ridlo MR, Kim EH, Kim GA. MicroRNA-210 Regulates Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Apoptosis in Porcine Embryos. Animals. 2021; 11(1):221. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11010221

Chicago/Turabian StyleRidlo, Muhammad Rosyid, Eui Hyun Kim, and Geon A. Kim. 2021. "MicroRNA-210 Regulates Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Apoptosis in Porcine Embryos" Animals 11, no. 1: 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11010221

APA StyleRidlo, M. R., Kim, E. H., & Kim, G. A. (2021). MicroRNA-210 Regulates Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Apoptosis in Porcine Embryos. Animals, 11(1), 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11010221