Volatile Organic Compound Profiles Associated with Microbial Development in Feedlot Pellets Inoculated with Bacillus amyloliquefaciens H57 Probiotic

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Production of Beef Weaner Pellets

2.2. Pellet Storage and Sample Collection

- CA0, CA1, CA2 & CA3: Control pellets aged 0, 1, 2 & 3 months

- HA0, HA1, HA2 & HA3: H57 pellets aged 0, 1, 2 & 3 months

- Pellets stored at 5 °C (B):

- CB1, CB2 & CB3: Control pellets aged 1, 2 & 3 months

- HB1, HB2 & HB3: H57 pellets aged 1, 2 & 3 months

2.3. Cell Counting Procedure for H57 Spore and Vegetative

2.4. Gas Chromatography Mass Spectroscopy Analysis (GC/MS)

2.5. Data Analysis

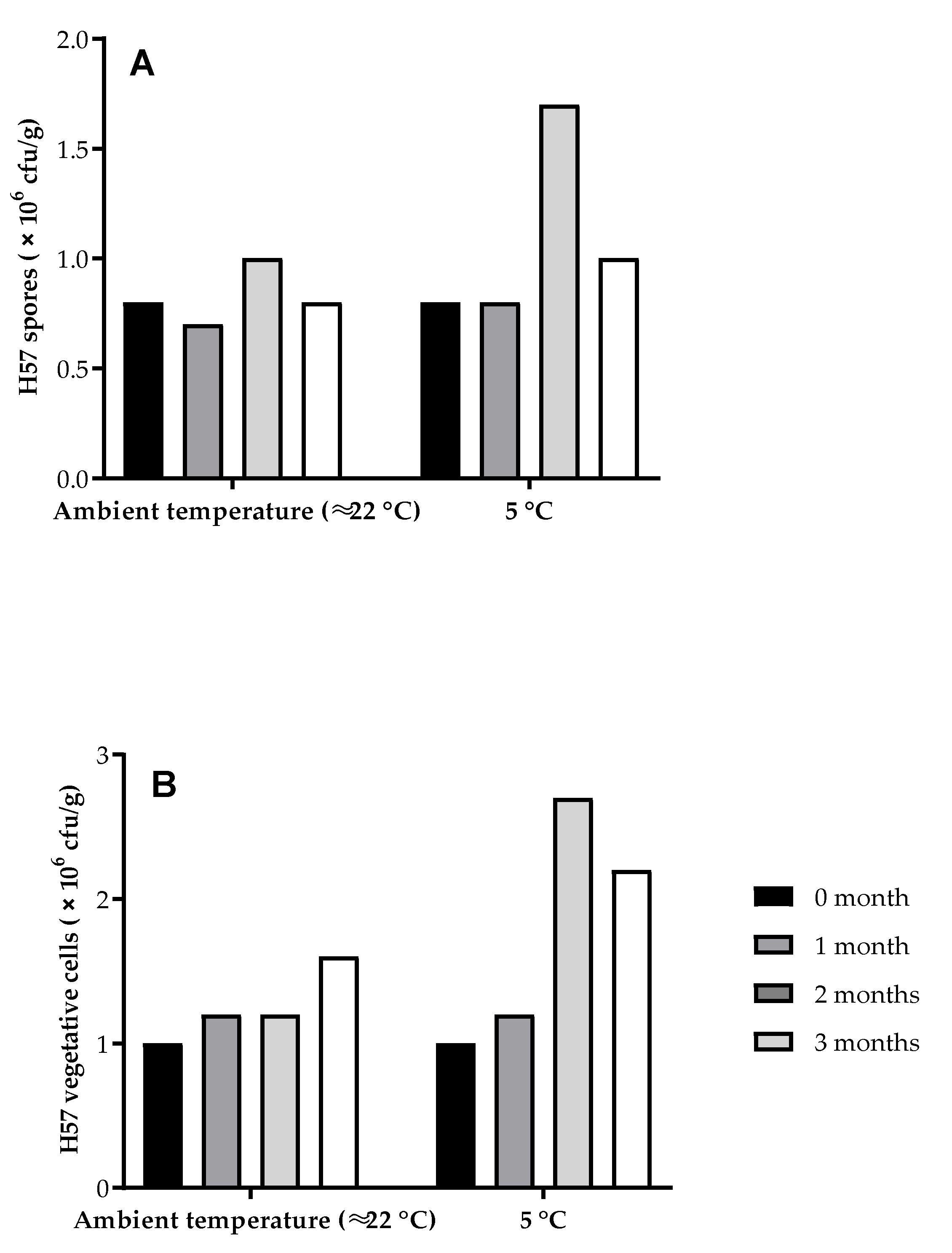

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buttery, R.G.; Kamm, J.A.; Ling, L.C. Volatile components of red clover leaves, flowers, and seed pods: Possible insect attractants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1984, 32, 254–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tava, A.; Berardo, N.; Odoardi, M. Composition of essential oil of tall fescue. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 1455–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tava, A.; Berardo, N.; Cunico, C.; Romani, M.; Odoardi, M. Cultivar differences and seasonal changes of primary metabolites and flavor constituents in tall fescue in relation to palatability. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1995, 43, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akakabe, Y. The effect of odor in palatability for cattle forage Italian ryegrass hay and silage. Aroma Res. 2009, 10, 358–363. [Google Scholar]

- Cannas, A.; Mereu, A.; Decandia, M.; Molle, G. Role of sensorial perceptions in feed selection and intake by domestic herbivores. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 8, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirstine, W.; Galbally, I.; Ye, Y.; Hooper, M. Emissions of volatile organic compounds (primarily oxygenated species) from pasture. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1998, 103, 10605–10619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatanaka, A.; Kajiwara, T.; Matsui, K. The biogeneration of green odour by green leaves and it's physiological functions -past, present and future. Z. Naturforsch 1995, 50, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayland, H.F.; Flath, R.A.; Shewmaker, G.E. Volatiles from fresh and air-dried vegetative tissues of tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea schreb.): Relationship to cattle preference. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 2204–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapisarda, T.; Mereu, A.; Cannas, A.; Belvedere, G.; Licitra, G.; Carpino, S. Volatile organic compounds and palatability of concentrates fed to lambs and ewes. Small Rumin. Res. 2012, 103, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristian, K.; Nielsen, P.V.; Larsen, T.O. Fungal volatiles: Biomarkers of good and bad food quality. In Food Mycology: A Multifaceted Approach to Fungi and Food; Samson, R.A., Dijksterhuis, J., Eds.; CRC Press LLC: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2007; pp. 279–301. [Google Scholar]

- Buśko, M.; Jeleń, H.; Góral, T.; Chmielewski, J.; Stuper, K.; Szwajkowska-Michałek, L.; Tyrakowska, B.; Perkowski, J. Volatile metabolites in various cereal grains. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2010, 27, 1574–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.N.; Tuma, D.; Abramson, D.; Muir, W.E. Fungal volatiles associated with moldy grain in ventilated and non-ventilated bin-stored wheat. Mycopathologia 1988, 101, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeleń, H.; Wasowicz, E. Volatile fungal metabolites and their relation to the spoilage of agricultural commodities. Food Rev. Int. 1998, 14, 391–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeleń, H.H.; Majcher, M.; Zawirska-Wojtasiak, R.; Wiewiórowska, M.; Wa̧sowicz, E. Determination of geosmin, 2-methylisoborneol, and a musty-earthy odor in wheat grain by SPME-GC-MS, profiling volatiles, and sensory analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 7079–7085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Undi, M.; Wittenberg, K.M.; Holliday, N.J. Occurrence of fungal species in stored alfalfa forage as influenced by moisture content at baling and temperature during storage. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 1997, 77, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton, A.; Zwaenepoel, P. Succession of moist hay mycoflora during storage. Can. J. Microbiol. 1991, 37, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittenberg, K. Microbial and nutritive changes in forage during harvest and storage as hay. Session 1997, 14, 265–270. [Google Scholar]

- Borreani, G.; Tabacco, E.; Schmidt, R.J.; Holmes, B.J.; Muck, R.E. Silage review: Factors affecting dry matter and quality losses in silages. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 3952–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dulcet, E.; Kaszkowiak, J.; Borowski, S.; Mikołajczak, J. Effects of microbiological additive on baled wet hay. Biosyst. Eng. 2006, 95, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Dart, P. Testing Hay Treated with Mould-Inhibiting, Biocontrol Inoculum: Microbial Inoculant for Hay; Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation: Kingston, Australia, 2005.

- Korpi, A.; Järnberg, J.; Pasanen, A.-L. Microbial volatile organic compounds. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2009, 39, 139–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Raza, W.; Shen, Q.; Huang, Q. Antifungal activity of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens NJN-6 volatile compounds against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Cubense Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 5942–5944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raza, W.; Ling, N.; Yang, L.; Huang, Q.; Shen, Q. Response of tomato wilt pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum to the volatile organic compounds produced by a biocontrol strain Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SQR-9. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Raza, W.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Ling, N.; Wei, Z.; Huang, Q.; Shen, Q. Effects of volatile organic compounds produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens on the growth and virulence traits of tomato bacterial wilt pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 7639–7650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dart, P. Storage evaluation of the effect of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens H57 on the control of fungal contamination in Ridley feed formulated pellets. Rep. Ridley AgriProducts 2011, 15528, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield, B.J. Microbial Community Structure and Functionality in Ruminants Fed the Probiotic Bacillus amyloliquefaciens H57. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Queensland, Bisbane, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, T.T.; Bang, N.N.; Dart, P.; Callaghan, M.; Klieve, A.; Hayes, B.; McNeill, D. Feed preference response of weaner bull calves to Bacillus amyloliquefaciens H57 probiotic and associated volatile organic compounds in high concentrate feed pellets. Animals 2021, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrman, T.J. Sampling: Procedures for Feed; Kansas State University Research and Extension: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan, W.F.; McCance, M.E. The microbiological examination of foods. In Laboratory Methods in Microbiology, Harrigan, W.F., McCance, M.E., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1966; pp. 106–133. [Google Scholar]

- SAS. SAS/STAT User’s Guide, Version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Camo. The Unscrambler X User’s Guide, Version 10.5; Camo Software AS: Oslo, Norway, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, H.; Martens, M. Multivariate Analysis of Quality: An Introduction; Wiley: New York City, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, J.; Borjesson, T.; Lundstedt, T.; Schnurer, J. Detection and quantification of ochratoxin A and deoxynivalenol in barley grains by GC-MS and electronic nose. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2002, 72, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; Brown, H.; Beales, N.; Williams, B. Characterisation of volatile indicator molecules for the early onset of spoilage in wheat grain and establishment of a link with formation of spoilage odours. In Development and Testing of a Sensor to Detect Microbiological Spoilage in Grain; Brown, H., Ratcliffe, N., Voysey, P., Williams, J., Spencer-Phillips, P., de Lacey Costello, B., Beales, N., Salmon, S., Gunson, H., Sivanand, P., et al., Eds.; The University of the West of England: Bristol, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, K.; Zhang, H.; Thornton, M.; Sun, L.; Wang, Z.; Xu, X.; Dong, L. Comprehensive evaluation of malt volatile compounds contaminated by Fusarium graminearum during malting. J. Inst. Brew. 2017, 123, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Magan, N.; Evans, P. Volatiles as an indicator of fungal activity and differentiation between species, and the potential use of electronic nose technology for early detection of grain spoilage. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2000, 36, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combet, E.; Eastwood, D.C.; Burton, K.S.; Combet, E.; Henderson, J.; Henderson, J.; Combet, E. Eight-carbon volatiles in mushrooms and fungi: Properties, analysis, and biosynthesis. Mycoscience 2006, 47, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennerman, K.K.; Al-Maliki, H.S.; Lee, S.; Bennett, J.W. Fungal volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and the genus Aspergillus. In New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Gupta, V.K., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2016; pp. 95–115. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski, E.; Libbey, L.M.; Stawicki, S.; Wasowicz, E. Identification of the predominant volatile compounds produced by Aspergillus flavus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1972, 24, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, E.; Stawicki, S.; Wasowicz, E. Volatile flavor compounds produced by molds of Aspergillus, Penicillium, and fungi Imperfecti. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1974, 27, 1001–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Börjesson, T.; Stöllman, U.; Adamek, P.; Kaspersson, A. Analysis of volatile compounds for detection of molds in stored cereals. Cereal Chem. 1989, 66, 300–304. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, C.; Scholl, S. Volatile metabolites of some barley storage molds. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1989, 8, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buśko, M.; Stuper, K.; Jeleń, H.; Góral, T.; Chmielewski, J.; Tyrakowska, B.; Perkowski, J. Comparison of volatiles profile and contents of Trichothecenes group b, Ergosterol, and ATP of bread wheat, durum wheat, and triticale grain naturally contaminated by mycobiota. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rajini, K.S.; Aparna, P.; Sasikala, C.; Ramana, C.V. Microbial metabolism of pyrazines. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 37, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Börjesson, T.S.; Stöllman, U.M.; Schnürer, J.L. Off-odorous compounds produced by molds on oatmeal agar: Identification and relation to other growth characteristics. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1993, 41, 2104–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Raza, W.; Shen, Q.; Huang, Q. Biocontrol traits and antagonistic potential of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain NJZJSB3 against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, a causal agent of canola stem rot. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 24, 1327–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lemfack, M.C.; Gohlke, B.O.; Toguem, S.M.T.; Preissner, S.; Piechulla, B.; Preissner, R. mVOC 2.0: A database of microbial volatiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D1261–D1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schofield, B.J.; Skarshewski, A.; Lachner, N.; Ouwerkerk, D.; Klieve, A.V.; Dart, P.; Hugenholtz, P. Near complete genome sequence of the animal feed probiotic, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens H57. Stand. Genom. 2016, 11, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nanjundan, J.; Ramasamy, R.; Uthandi, S.; Ponnusamy, M. Antimicrobial activity and spectroscopic characterization of surfactin class of lipopeptides from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SR1. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 128, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannaa, M.; Kim, K.D. Influence of temperature and water activity on deleterious fungi and mycotoxin production during grain storage. Mycobiology 2017, 45, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munoz, L.R.; Pacheco, W.J.; Hauck, R.; Macklin, K.S. Evaluation of commercially manufactured animal feeds to determine presence of Salmonella, Escherichia coli, and Clostridium perfringens. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2021, 30, 100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udhayavel, S.; Thippichettypalayam Ramasamy, G.; Gowthaman, V.; Malmarugan, S.; Senthilvel, K. Occurrence of Clostridium perfringens contamination in poultry feed ingredients: Isolation, identification and its antibiotic sensitivity pattern. Anim Nutr. 2017, 3, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minooeianhaghighi, M.H.; Marvi Moghadam Shahri, A.; Taghavi, M. Investigation of feedstuff contaminated with aflatoxigenic fungi species in the semi-arid region in northeast of Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Chemical Classification | Compound Name | Intercept | Coefficient 2 | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H57 | Temperature | Time | H57 | Temperature | Time | |||

| Microbial volatile organic compounds 3 | ||||||||

| Aldehydes | Butanal, 3-methyl- | 21.11 | 0.48 | −1.09 | −1.69 | 0.407 | 0.102 | 0.536 |

| Acids | Acetic acid | 7.96 | −0.22 | −0.86 | −2.14 | 0.717 | 0.212 | 0.756 |

| Aldehydes | Pentanal | 3.82 | −0.54 | 1.06 | 7.05 | 0.036 | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| Nitrogen compounds | Pyrazine | 15.79 | −0.21 | −0.96 | −1.93 | 0.719 | 0.155 | 0.824 |

| Acids | Propionic acid | 0.68 | −0.95 | 0.71 | −0.01 | 0.089 | 0.218 | 0.644 |

| Nitrogen compounds | Pyridine | 6.95 | 0.43 | −0.51 | −4.08 | 0.391 | 0.354 | 0.444 |

| Alcohols | 1-Pentanol | −0.39 | −0.81 | 1.30 | 5.49 | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Aldehydes | Hexanal | 2.06 | −0.80 | 1.00 | 6.13 | 0.017 | 0.009 | <0.001 |

| Nitrogen compounds | Pyrazine, methyl- | 18.56 | −0.08 | 0.22 | 0.51 | 0.898 | 0.757 | 0.867 |

| Aldehydes | Furfural | 13.54 | −0.83 | −1.01 | −0.59 | 0.083 | 0.055 | 0.550 |

| Alcohols | 2-Furanmethanol | 9.43 | −0.88 | −1.23 | −2.73 | 0.059 | 0.021 | 0.499 |

| Ketones | 2-Heptanone | 9.93 | −0.21 | −0.46 | 0.97 | 0.624 | 0.331 | 0.118 |

| Aldehydes | Heptanal | −1.06 | −0.70 | 1.41 | 4.23 | 0.094 | 0.008 | 0.024 |

| Nitrogen compounds | Pyrazine, 2,5-dimethyl- | 14.15 | −0.44 | −0.04 | −0.07 | 0.386 | 0.939 | 0.425 |

| Heterocyclic compound | Furan, 2-pentyl- | 2.32 | −0.75 | 0.98 | 6.17 | 0.013 | 0.005 | <0.001 |

| Alcohols | 1-Octen-3-ol | 1.64 | −0.61 | 1.28 | 6.11 | 0.050 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Aldehydes | Benzaldehyde | 18.79 | 0.19 | −1.28 | −2.53 | 0.703 | 0.036 | 0.677 |

| Nitrogen compounds | Pyrazine, 2-ethyl-5-methyl- | 12.47 | −0.22 | 0.28 | 1.09 | 0.686 | 0.638 | 0.785 |

| Aldehydes | Octanal | −0.93 | 0.03 | 0.92 | 2.75 | 0.963 | 0.169 | 0.257 |

| Aldehydes | 2,4-Heptadienal, (E,E)- | 4.03 | −0.53 | 1.24 | 6.13 | 0.088 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| Aldehydes | Nonanal | 0.71 | −0.50 | 1.40 | 6.10 | 0.048 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Others | 2(3H)-Furanone, 5-ethyldihydro- | 2.49 | −0.34 | 1.36 | 6.74 | 0.141 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Aldehydes | 2-Nonenal, (E)- | 1.30 | −0.68 | 0.85 | 2.02 | 0.239 | 0.181 | 0.503 |

| Aldehydes | 2,4-Decadienal, (E,E)- | 2.54 | −0.61 | 1.07 | 6.40 | 0.009 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Non-microbial volatile organic compounds | ||||||||

| Ketones | 2-Propanone, 1-hydroxy- | 9.3 | −0.37 | −1.06 | −3.50 | 0.487 | 0.090 | 0.389 |

| Others | Ethane, 1,2-bis[(4-amino-3-furazanyl)oxy]- | 1.73 | −0.02 | −1.04 | −0.74 | 0.976 | 0.101 | 0.736 |

| Others | 1-Hexyne, 5-methyl- | −0.36 | −0.53 | 0.62 | 1.87 | 0.356 | 0.321 | 0.218 |

| Nitrogen compounds | Pyrazine, ethyl- | 17.82 | −0.13 | −0.09 | −0.07 | 0.847 | 0.903 | 0.998 |

| Others | Cyclotetrasiloxane, octamethyl- | 3.70 | 0.41 | 0.25 | −1.65 | 0.409 | 0.637 | 0.555 |

| Ketones | 4-Cyclopentene-1,3-dione | 14.98 | −1.25 | −0.82 | −2.14 | 0.010 | 0.077 | 0.677 |

| Aldehydes | 2-Heptenal, (Z)- | −0.51 | −0.61 | 0.82 | 3.32 | 0.217 | 0.135 | 0.076 |

| Others | 1,3-Hexadiene, 3-ethyl-2-methyl- | 1.75 | −0.65 | 0.99 | 6.82 | 0.042 | 0.009 | <0.001 |

| Heterocyclic compound | 1H-Pyrrole-2-carboxaldehyde | 9.54 | 0.19 | −0.03 | −0.49 | 0.752 | 0.967 | 0.612 |

| Others | 9-Hexadecenoic acid, phenylmethyl ester, (Z)- | 13.94 | −0.02 | −1.19 | −3.31 | 0.967 | 0.053 | 0.176 |

| Aldehydes | 2-Decenal, (E)- | 1.78 | −0.39 | 1.34 | 4.97 | 0.115 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Others | 4-Hydroxy-2-methylacetophenone | 3.46 | −0.24 | 0.68 | 1.94 | 0.704 | 0.321 | 0.736 |

| Aldehydes | (E)-Tetradec-2-enal | 0.90 | −0.33 | 0.20 | 1.84 | 0.624 | 0.778 | 0.727 |

| Others | 17-Octadecynoic acid, methyl ester | 8.43 | 0.64 | −0.84 | −0.27 | 0.221 | 0.143 | 0.524 |

| Alcohols | Butylated hydroxytoluene | 4.89 | 0.97 | 0.26 | −2.29 | 0.040 | 0.557 | 0.071 |

| Acids | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)- | −0.25 | −0.41 | 1.39 | 5.96 | 0.106 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ngo, T.T.; Dart, P.; Callaghan, M.; Klieve, A.; McNeill, D. Volatile Organic Compound Profiles Associated with Microbial Development in Feedlot Pellets Inoculated with Bacillus amyloliquefaciens H57 Probiotic. Animals 2021, 11, 3227. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11113227

Ngo TT, Dart P, Callaghan M, Klieve A, McNeill D. Volatile Organic Compound Profiles Associated with Microbial Development in Feedlot Pellets Inoculated with Bacillus amyloliquefaciens H57 Probiotic. Animals. 2021; 11(11):3227. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11113227

Chicago/Turabian StyleNgo, Thi Thuy, Peter Dart, Matthew Callaghan, Athol Klieve, and David McNeill. 2021. "Volatile Organic Compound Profiles Associated with Microbial Development in Feedlot Pellets Inoculated with Bacillus amyloliquefaciens H57 Probiotic" Animals 11, no. 11: 3227. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11113227

APA StyleNgo, T. T., Dart, P., Callaghan, M., Klieve, A., & McNeill, D. (2021). Volatile Organic Compound Profiles Associated with Microbial Development in Feedlot Pellets Inoculated with Bacillus amyloliquefaciens H57 Probiotic. Animals, 11(11), 3227. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11113227