Using Nutritional Strategies to Shape the Gastro-Intestinal Tracts of Suckling and Weaned Piglets

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

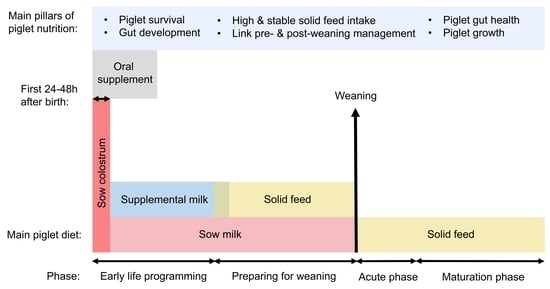

2. Early Nutrition Interventions

2.1. Oral Supplementation

2.2. Supplemental Milk

| Reference | Dietary Intervention(s) | Intervention Period (Age) | Age at Sampling | Effects on Gut Development versus a Control Milk Replacer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [53] | Polydextrose (2 g/L) + Fructo-oligosaccharides (2 g/L) | 1–14 | 7, 14 | Lowers digestive enzyme production at both sampling days: ↓ Lactase, sucrase, disaccharidase and aminopeptidase N activity (ileum) ↓ Dipeptidyl peptidase IV activity (jejunum, ileum) = Small-intestine weight and length = Cytokine expression (ileum) = Faecal consistency |

| [61] | Polydextrose (2 g/L) + Galacto-oligosaccharides (2 g/L) | 2–33 | 33 | = Small-intestine weight and length ↓ Total volatile fatty acids (colon, no differences in caecum and faeces) ↑ Dry matter of colon digesta ↓ Dry matter of faeces |

| [53] | Galacto-oligosaccharides (2 g/L) + Inulin (2 g/L) | 1–21 | 21 | = Small-intestine weight and length = Immune cell population = Nitric oxide synthase activity = Cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α in blood |

| [54] | Galacto-oligosaccharides: 0.8% | 1–26 | 4, 27 | Modulates gut microbial population and improves intestinal morphology and barrier function: ↑ Duodenum villus height, villus area, villus-to-crypt ratio (d4), villus width (d27) ↑ Jejunum villus height (d27) ↓ Caecum pH (d4, no other pH differences) ↑ Caecum butyric acid (d27) ↑ Lactobacillus, bifidobacterium in faeces (d27) ↑ Maltase activity (colon: d4, caecum: d27) ↓ Lactase, sucrase, maltase activity (ileum, d27) ↑ mRNA expression of defensins (colon, d4) ↑ mRNA expression of tight-junction proteins in different segments of the intestine (d4, d27) ↑ Tight-junction protein expression (duodenum, colon, d27) ↑ Secretory IgA from saliva (from d19) |

| [62] | Galacto-oligosaccharides: 8 mg/mL | 3–25 | 25 | ↑ Relative large-intestine weight in males, but not females = Small-intestine weight ↓ Haematology and clinical chemistry blood parameters |

| [63] | Galacto-oligosaccharides (7 g/L) + milk fat globule membrane-10 (5 g/L) + polydextrose (2.4 g/L) + bovine lactoferrin (0.6 g/L) | 3–33 | 33 | Modulates gut microbiota population and stimulates gut function: = Intestinal weight and length, small-intestinal morphology ↓ Colon area ↑ Parabacteroides, Clostridium IV, Lutispora (colon) ↓ Mogibacterium, Collinsella, Klebsiella, Escherichia-Shigella, Eubacterium, Roseburia (colon) ↑ Lactase activity (jejunum), lactase-to-sucrase activity (duodenum, ileum; no difference in jejunum) = Sucrose activity (in any part) ↑ Vasoactive intestinal peptide expression (ileum) |

| [56] | Bovine colostrum | 23–31 | 31 | Reduces colonisation by E. coli and modulates intestinal immune system: ↓ Diarrhoea frequency ↓ E. coli in jejunal and ileal tissue and content in non-inoculated intestinal samples, but not in ETEC F18-inoculated samples ↓ TLR-4 and IL-2 gene expression (jejunal and ileal mucosa) = Ig concentrations in mucosa and plasma |

| [55] | VP: palm + rapeseed oil VM: VP + milk fat globule membranes (MFGM) MM: VM + sunflower + milk fat | 2–28 | 7, 28 |

|

| [64] | Fat origin: only plant lipids or a half-half mixture of plant and dairy lipids | 2–28 | 33 | = Short-chain fatty acids (faeces) |

| [65] | Yeast β-glucans: 5, 50 or 250 mg/L | 2–21 | 7, 21 | = Small-intestine length and weight = Ileal crypt depth, villus height, ascending colon-cuff depth = T cell phenotypes, cytokine gene expression, cell proliferation |

| [66] | Wheat: up to 40% | 11–25 1 | 25 | ↓ Relative full stomach weight ↑ Sucrase, maltase ↑ Leukocytes, neutrophils |

| [67] | Pectin: 2 g/L or 10 g/L | 2–23 |

|

3. Preparing Piglets for Weaning

3.1. Pre-Weaning Nutritional Strategies to Stimulate Individual Dry-Matter Intake

3.2. Pre-Weaning Nutritional Strategies to Modulate Gut Health

3.3. Transition Diet

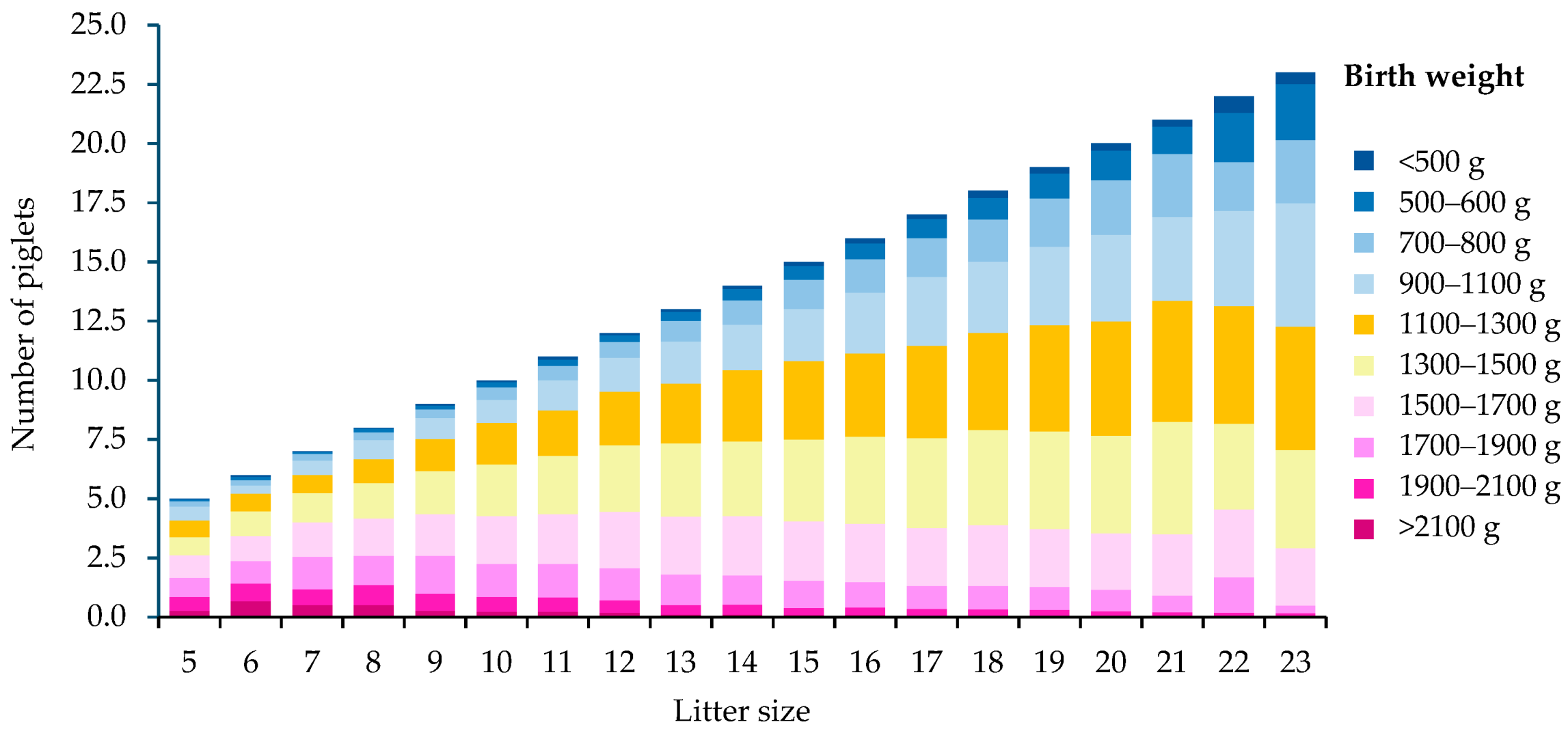

4. Are all Weaned Piglets Alike?

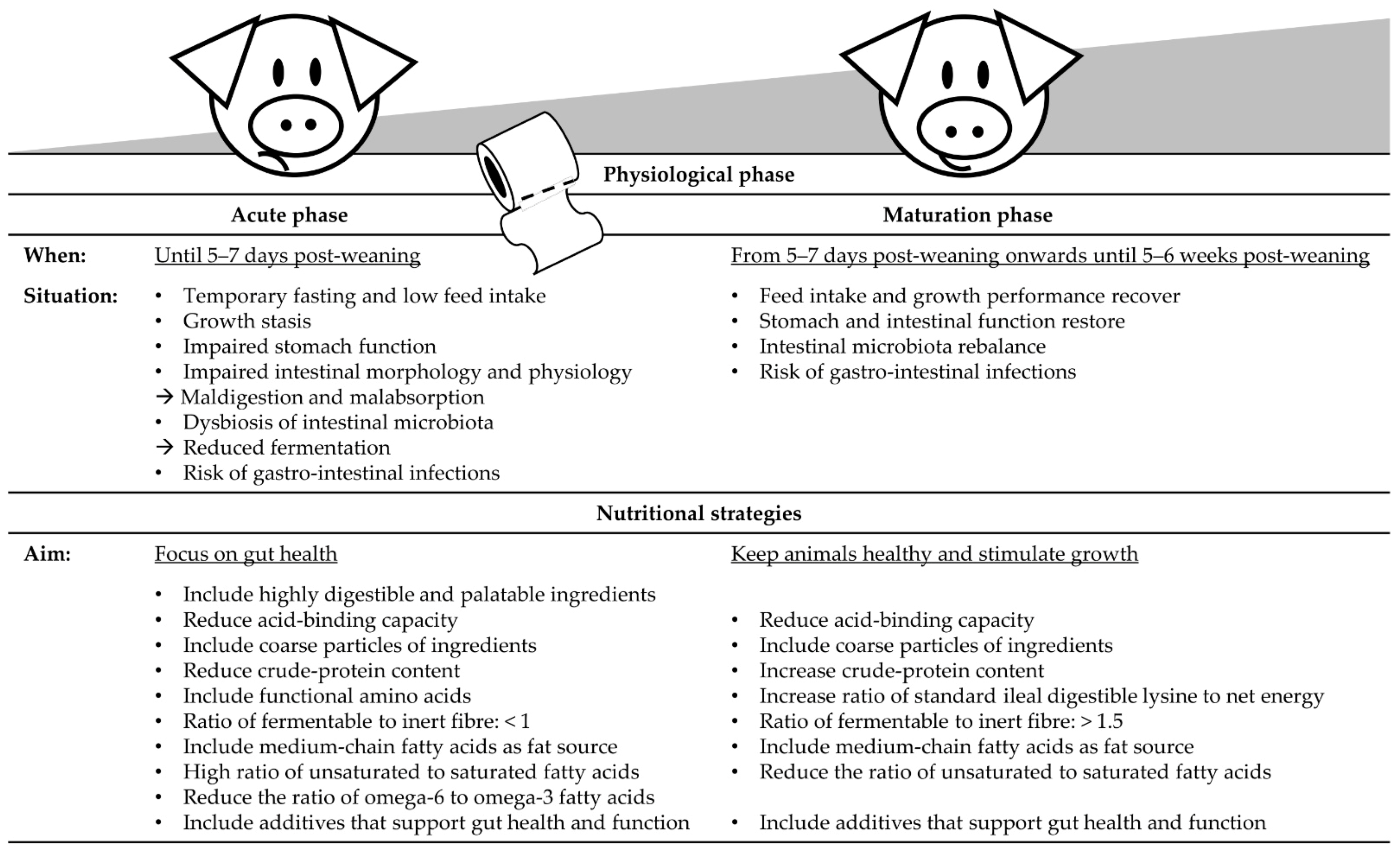

5. Post-Weaning Nutritional Strategies during the Acute Phase

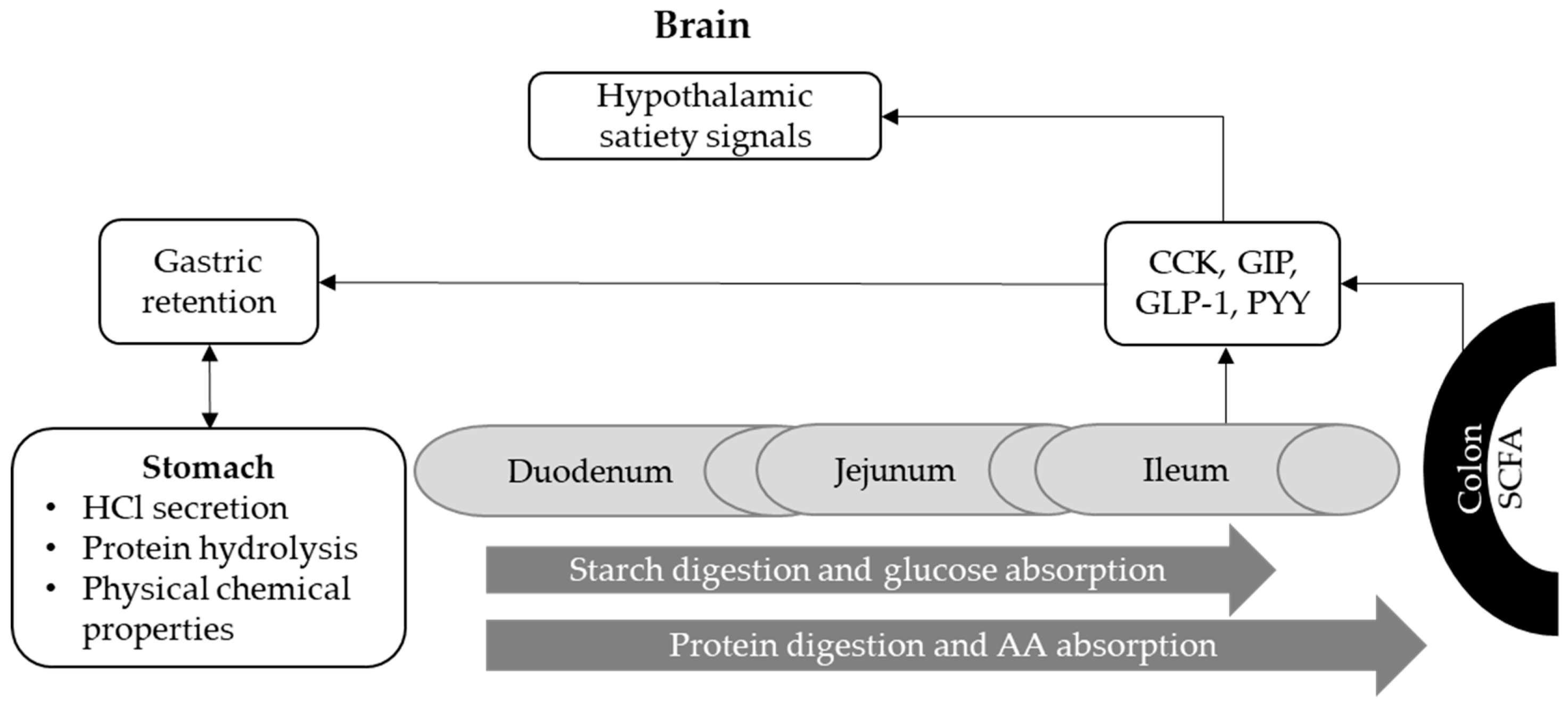

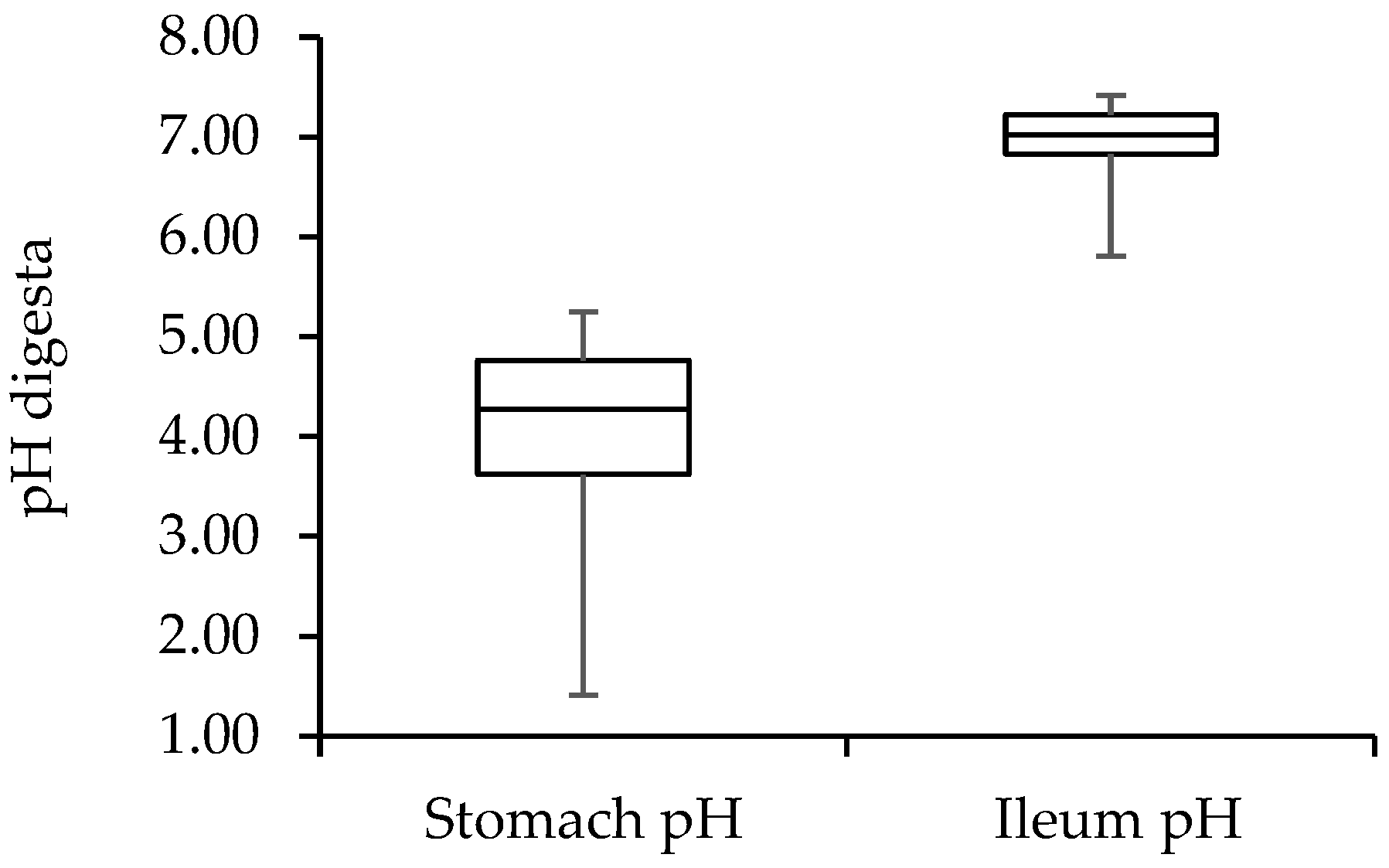

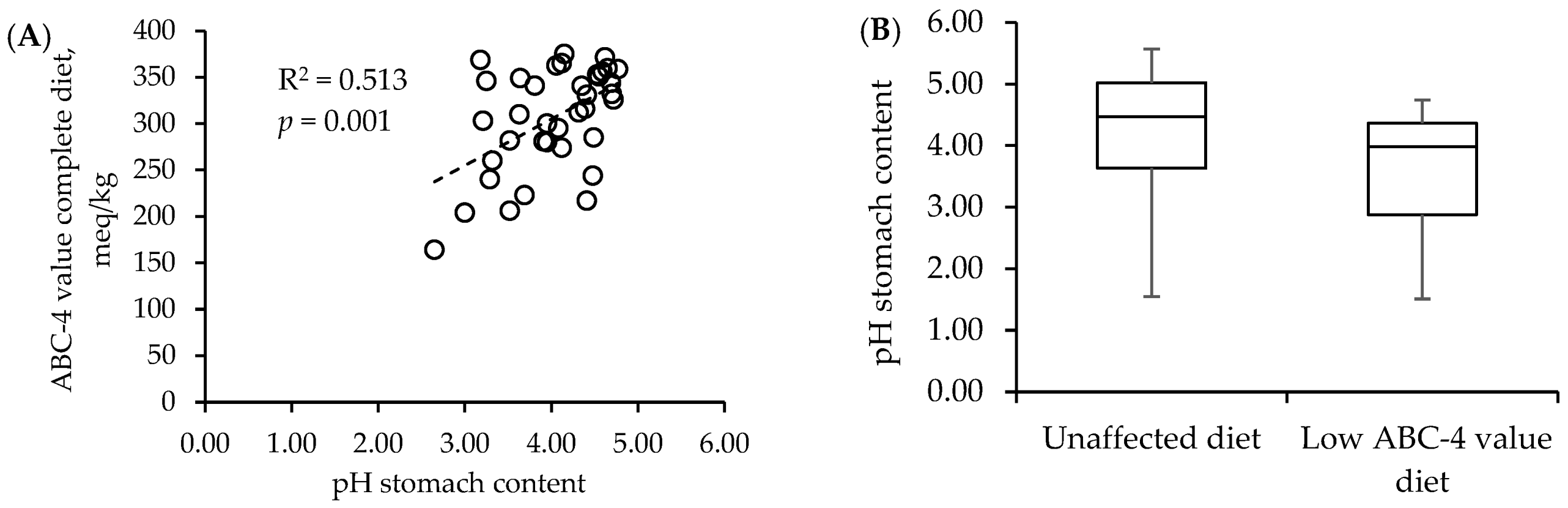

5.1. Nutritional Strategies to Support Stomach Functioning

5.1.1. The Role of Feedstuffs and Minerals

5.1.2. The Role of Organic Acids and Their Interaction with Feed Ingredients

5.2. Factors that Prolong Stomach Retention, Promote Gut Health and Modulate Digestion Kinetics along the Small Intestine

5.2.1. The Role of Particle Size or Feed Structure

5.2.2. The Role of Heat Treatment

5.2.3. The Role of Physicochemical Characteristics

5.3. The Role of Main Nutrients in Supporting the Health and Function of the Gastro-Intestinal Tract

5.3.1. The Role of Crude Protein Level, Quality and Functional Amino Acids

5.3.2. The Role of Dietary Fibres

5.3.3. The Role of Fat

6. Post-Weaning Nutritional Strategies during the Maturation Phase

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rutherford, K.M.D.; Baxter, E.M.; D’Eath, R.B.; Turner, S.P.; Arnott, G.; Roehe, R.; Ask, B.; Sandøe, P.; Moustsen, V.A.; Thorup, F.; et al. The welfare implications of large litter size in the domestic pig I: Biologica factors. Anim. Welf. 2013, 22, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, A.D.; Aalhus, J.L.; Williams, N.H.; Patience, J.F. Impact of piglet birth weight, birth order, and litter size on subsequent growth performance, carcass quality, muscle composition, and eating quality of pork. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88, 2767–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, S.; Matheson, S.; Baxter, E. Genetic influences on intra-uterine growth retardation of piglets and management interventions for low birth weight piglets. In Nutition of Hyperprolific Sows; Editorial Agricola Española, Ed.; Novus International, Inc.: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 207–235. ISBN 978-84-47884-05-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hales, J.; Moustsen, V.A.; Nielsen, M.B.F.; Hansen, C.F. Individual physical characteristics of neonatal piglets affect preweaning survival of piglets born in a noncrated system. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 4991–5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, C.V.; Sbardella, P.E.; Bernardi, M.L.; Coutinho, M.L.; Vaz, I.S.; Wentz, I.; Bortolozzo, F.P. Effect of birth weight and colostrum intake on mortality and performance of piglets after cross-fostering in sows of different parities. Prev. Vet. Med. 2014, 114, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiniou, N.; Dagorn, J.; Gaudré, D. Variation of piglets’ birth weight and consequences on subsequent performance. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2002, 78, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, S.P.; Jansman, A.J.M.; Verstegen, M.W.A.; Awati, A.; Buist, W.; den Hartog, L.A.; van Hees, H.M.J.; Quiniou, N.; Hendriks, W.H.; Gerrits, W.J.J. Analysis of factors to predict piglet body weight at the end of the nursery phase. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90, 3243–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huting, A.M.S.; Sakkas, P.; Wellock, I.; Almond, K.; Kyriazakis, I. Once small always small? To what extent morphometric characteristics and postweaning starter regime affect pig lifetime growth performance. Porcine Health Manag. 2018, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliviero, C.; Junnikkala, S.; Peltoniemi, O. The challenge of large litters on the immune system of the sow and the piglets. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2019, 54, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amdi, C.; Lynegaard, J.C.; Thymann, T.; Williams, A.R. Intrauterine growth restriction in piglets alters blood cell counts and impairs cytokine responses in peripheral mononuclear cells 24 days post-partum. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo Yagüe, A. Use of hyperprolific sows and implications. In Nutition of Hyperprolific Sows; Editorial Agricola Española, Ed.; Novus International, Inc.: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 11–38. ISBN 978-84-47884-05-5. [Google Scholar]

- Le Dividich, J.; Rooke, J.A.; Herpin, P. Nutritional and immunological importance of colostrum for the new-born pig. J. Agric. Sci. 2005, 143, 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaluwé, R.; Maes, D.; Wuyts, B.; Cools, A.; Piepers, S.; Janssens, G.P.J. Piglets’ colostrum intake associates with daily weight gain and survival until weaning. Livest. Sci. 2014, 162, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amdi, C.; Krogh, U.; Flummer, C.; Oksbjerg, N.; Hansen, C.F.; Theil, P.K. Intrauterine growth restricted piglets defined by their head shape ingest insufficient amounts of colostrum. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 5605–5613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynegaard, J.C.; Hales, J.; Nielsen, M.N.; Hansen, C.F.; Amdi, C. The stomach capacity is reduced in intrauterine growth restricted piglets compared to normal piglets. Animals 2020, 10, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devillers, N.; Le Dividich, J.; Prunier, A. Influence of colostrum intake on piglet survival and immunity. Animal 2011, 5, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Declerck, I.; Dewulf, J.; Sarrazin, S.; Maes, D. Long-term effects of colostrum intake in piglet mortality and performance. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 1633–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasdal, G.; Østensen, I.; Melišová, M.; Bozděchová, B.; Illmann, G.; Andersen, I.L. Management routines at the time of farrowing-effects on teat success and postnatal piglet mortality from loose housed sows. Livest. Sci. 2011, 136, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferret-Bernard, S.; Le Huërou-Luron, I. Development of the intestinal immune system in young pigs—Role of the microbial environment. In The Suckling and Weaned Piglet; Farmer, C., Ed.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 159–177. ISBN 978-90-8686-343-3. [Google Scholar]

- Friendship, R.M. Diseases of piglets. In The Suckling and Weaned Piglet; Farmer, C., Ed.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 297–309. ISBN 978-90-8686-343-3. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, H.; Smidt, H. Microbiota development in piglets. In The Suckling and Weaned Piglet; Farmer, C., Ed.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 179–205. ISBN 978-90-8686-343-3. [Google Scholar]

- Laine, T.M.; Lyytikäinen, T.; Yliaho, M.; Anttila, M. Risk factors for post-weaning diarrhoea on piglet producing farms in Finland. Acta Vet. Scand. 2008, 50, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallès, J.P.; Boudry, G.; Favier, C.; Le Floc’h, N.; Luron, I.; Montagne, L.; Oswald, I.P.; Pié, S.; Piel, C.; Sève, B. Gut function and dysfunction in young pigs: Physiology. Anim. Res. 2004, 53, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commision. Regulation (EC) No 1831/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2003 on Additives for Use in Animal Nutrition. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32003R1831&from=EN (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- More, S.J. European perspectives on efforts to reduce antimicrobial usage in food animal production. Ir. Vet. J. 2020, 73, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commision. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/1095 of July 2016 Concerning the Authorisation of Zinc Acetate Dihydrate, Zinc Chloride Anhydrous, Zinc Oxide, Zinc Sulphate Heptahydrate, Zinc Sulphate Monohydrate, et Cetera. Available online: https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/e983f6f8-43ff-11e6-9c64-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- European Commision. Commisson Implementing Regulation (EU) No 2018/1039 of 23 July 2018 Concerning the Authorisation of Copper(II) Diacetate Monohydrate, Copper(II) Carbonate Dihydroxy Monohydrate, Copper(II) Chloride Dihydrate, Copper(II) Oxide, et Cetera. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.L_.2018.186.01.0003.01.ENG&toc=OJ%3AL%3A2018%3A186%3ATOC (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Gebhardt, J.T.; Tokach, M.D.; Dritz, S.S.; DeRouchey, J.M.; Woodworth, J.C.; Goodband, R.D.; Henry, S.C. Postweaning mortality in commercial swine production. I: Review of non-infectious contributing factors. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2020, 4, 485–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, J.T.; Tokach, M.D.; Dritz, S.S.; DeRouchey, J.M.; Woodworth, J.C.; Goodband, R.D.; Henry, S.C. Postweaning mortality in commercial swine production II: Review of infectious contributing factors. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2020, 4, 462–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GD. Monitoring Diergezondheid Varken: Rapportage Tweede Halfjaar. 2019. Available online: https://www.gddiergezondheid.nl/~/media/Files/Monitoringsflyers/Varken/Monitoring_varken_2019-2_WEB.ashx (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Pluske, J.R.; Turpin, D.L.; Kim, J.C. Gastrointestinal tract (gut) health in the young pig. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 4, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Feng, C.; Tao, S.; Li, N.; Zuo, B.; Han, D.; Wang, J. Maternal imprinting of the neonatal microbiota colonization in intrauterine growth restricted piglets: A review. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 10, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, E.M.; Rutherford, K.M.D.; D’Eath, R.B.; Arnott, G.; Turner, S.P.; Sandøe, P.; Moustsen, V.A.; Thorup, F.; Edwards, S.A.; Lawrence, A.B. The welfare implications of large litter size in the domestic pig II: Management factors. Anim. Welf. 2013, 22, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, E.M.; Schmitt, O.; Pedersen, L.J. Managing the litter from hyperprolific sows. In The Suckling and Weaned Piglet; Farmer, C., Ed.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 71–106. ISBN 978-90-8686-343-3. [Google Scholar]

- Widdowson, E.M.; Colombo, V.E.; Artavanis, C.A. Changes in the organs of pigs in response to feeding for the first 24 h after birth. Biol. Neonate 1976, 28, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypek, T.; Valverde Piedra, J.L.; Skrzypek, H.; Wolinski, J.; Kazimierczak, W.; Szymanczyk, S.; Pawlowska, M.; Zabielski, R. Light and scanning electron microscopy evalutation of the postnatal small intestinal mucosa development in pigs. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2005, 56, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.J.; Mellor, D.J.; Tungthanathanich, P.; Birtles, M.J.; Reynolds, G.W.; Simpson, H.V. Growth and morphological changes in the small and the large intestine in piglets during the first three days after birth. J. Dev. Physiol. 1993, 18, 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Mi, J.; Lv, N.; Gao, J.; Cheng, J.; Wu, R.; Ma, J.; Lan, T.; Liao, X. Lactation stage-dependency of the sow milk microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, G.; Hou, C.; Li, N.; Yu, H.; Shang, L.; Zhang, X.; Trevisi, P.; Yang, F.; et al. Maternal milk and fecal microbes guide the spatiotemporal development of mucosa-associated microbiota and barrier function in the porcine neonatal gut. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canibe, N.; O’Dea, M.; Abraham, S. Potential relevance of pig gut content transplantation for production and research. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, T.E.; Li, P.; Li, X.; Shimotori, K.; Sato, H.; Flynn, N.E.; Wang, J.; Knabe, D.A.; Wu, G. L-Glutamine or L-alanyl-L-glutamine prevents oxidant- or endotoxin-induced death of neonatal enterocytes. Amino Acids 2009, 37, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Schroyen, M.; Leblois, J.; Wavreille, J.; Soyeurt, H.; Bindelle, J.; Everaert, N. Effects of inulin supplementation to piglets in the suckling period on growth performance, postileal microbial and immunological traits in the suckling period and three weeks after weaning. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 72, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lépine, A.F.P.; Konstanti, P.; Borewicz, K.; Resink, J.W.; de Wit, N.J.; de Vos, P.; Smidt, H.; Mes, J.J. Combined dietary supplementation of long chain inulin and Lactobacillus acidophilus W37 supports oral vaccination efficacy against Salmonella Typhimurium in piglets. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schokker, D.; Fledderus, J.; Jansen, R.; Vastenhouw, S.A.; de Bree, F.M.; Smits, M.A.; Jansman, A.A.J.M. Supplementation of fructooligosaccharides to suckling piglets affects intestinal microbiota colonization and immune development. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96, 2139–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Wang, J.; Yu, H.; Wang, J.; Zhu, W. Effects of galacto-oligosaccharides on growth and gut function of newborn suckling piglets. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Han, D.; Ye, H.; Tao, S.; Pi, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, J. Short administration of combined prebiotics improved microbial colonization, gut barrier, and growth performance of neonatal piglets. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 20506–20516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, H.; Geervliet, M.; Jansen, C.A.; Rutten, V.P.M.G.; van Hees, H.; Groothuis, N.; Wells, J.M.; Savelkoul, H.F.J.; Tijhaar, E.; Smidt, H. Impact of yeast-derived β-glucans on the porcine gut microbiota and immune system in early life. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, W.L. Composition of sow colostrum and milk. In The Gestating and Lactating Sow; Farmer, C., Ed.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 193–230. ISBN 978-90-8686-253-5. [Google Scholar]

- Everaert, N.; van Cruchten, S.; Weström, B.; Bailey, M.; van Ginneken, C.; Thymann, T.; Pieper, R. A review on early gut maturation and colonization in pigs, including biological and dietary factors affecting gut homeostasis. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2017, 233, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Greeff, A.; Resink, J.W.; van Hees, H.M.J.; Ruuls, L.; Klaassen, G.J.; Rouwers, S.M.G.; Stockhofe-Zurwieden, N. Supplementation of piglets with nutrient-dense complex milk replacer improves intestinal development and microbial fermentation. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 1012–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Jia, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, X.; Sun, W.; Ma, C.; Xu, F.; Zhan, S.; Ma, L.; et al. Jejunal inflammatory cytokines, barrier proteins and microbiome-metabolome responses to early supplementary feeding of Bamei suckling piglets. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Zhu, Y.; Niu, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhu, W. The changes of colonic bacterial composition and bacterial metabolism induced by an early food introduction in a neonatal porcine model. Curr. Microbiol. 2018, 75, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radlowski, E. Early Nutrition Affects Intestinal Development and Immune Response in the Neonatal Piglet. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana-Champaign, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh, A.; Akbari, P.; Difilippo, E.; Schols, H.A.; Ulfman, L.H.; Schoterman, M.H.C.; Garssen, J.; Fink-Gremmels, J.; Braber, S. The piglet as a model for studying dietary components in infant diets: Effects of galacto-oligosaccharides on intestinal functions. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Huërou-Luron, I.; Bouzerzour, K.; Ferret-Bernard, S.; Ménard, O.; Le Normand, L.; Perrief, C.; Le Bourgot, C.; Jardin, J.; Bourlieu, C.; Carton, T.; et al. A mixture of milk and vegetable lipigs in infant formula changes gut digestion, mucosal immunity and microbiota composition in neonatal piglets. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 57, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiharto, S.; Poulsen, A.S.R.; Canibe, N.; Lauridsen, C. Effect of bovine colostrum feeding in comparison with milk replacer and natural feeding on the immune responses and colonisation of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in the intestinal tissue of piglets. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 923–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, S.; Sonntag, S.; Gallmann, E.; Jungbluth, T. Investigations into automatic feeding of suckling piglets with supplemental milk replacer. Landtechnik 2012, 67, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, S.L.; Edwards, S.A.; Kyriazakis, I. Management strategies to improve the performance of low birth weight pigs to weaning and their long-term consequences. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 92, 2280–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azain, M.J.; Tomkins, T.; Sowinski, J.S.; Arentson, R.A.; Jewell, D.E. Effect of supplemental pig milk replacer on litter performance: Seasonal variation in response. J. Anim. Sci. 1996, 74, 2195–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, Y.J.; Collins, A.M.; Smits, R.J.; Thomson, P.C.; Holyoake, P.K. Providing supplemental milk to piglets preweaning improves the growth but not survival of gilt progeny compared with sow progeny. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90, 5078–5085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, S.A.; Monaikul, S.; Patsavas, A.; Waworuntu, R.V.; Berg, B.M.; Dilger, R.N. Dietary polydextrose and galactooligosaccharide increase exploratory behavior, improve recognition memory, and alter neurochemistry in the young pig. Nutr. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruger, C.; Zhou, Y.; Thorsrud, B.A.; Morel-Despeisse, F.; Chappuis, E. Safety evaluation of α-galacto-oligosaccharides for use in infant formulas investigated in neonatal piglets. Toxicol. Res. Appl. 2017, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berding, K.; Wang, M.; Monaco, M.H.; Alexander, L.S.; Mudd, A.T.; Chichlowski, M.; Waworuntu, R.V.; Berg, B.M.; Miller, M.J.; Dilger, R.N.; et al. Prebiotics and bioactive milk fractions affect gut development, microbiota, and neurotransmitter expression in piglets. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2016, 63, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, M.; Dou, S.; Cahu, A.; Formal, M.; Le Normand, L.; Romé, V.; Nogret, I.; Ferret-Bernard, S.; Rhimi, M.; Cuinet, I.; et al. Addition of dairy lipids and probiotic Lactobacillus fermentum in infant formula programs gut microbiota and entero-insular axis in adult minipigs. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hester, S.N.; Comstock, S.S.; Thorum, S.C.; Monaco, M.H.; Pence, B.D.; Woods, J.A.; Donovana, S.M. Intestinal and systemic immune development and response to vaccination are unaffected by dietary (1,3/1,6)-β-D-glucan supplementation in neonatal piglets. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2012, 19, 1499–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amdi, C.; Pedersen, M.L.M.; Klaaborg, J.; Myhill, L.J.; Engelsmann, M.N.; Williams, A.R.; Thymann, T. Pre-weaning adaptation responses in piglets fed milk replacer with gradually increasing amounts of wheat. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, S.A.; Richards, J.D.; Bradley, C.L.; Pan, X.; Li, Q.; Dilger, R.N. Dietary pectin at 0.2% in milk replacer did not inhibit growth, feed intake, or nutrient digestibility in a 3-week neonatal pig study. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 114, 104669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weary, D.M.; Jasper, J.; Hötzel, M.J. Understanding weaning distress. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 110, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.M.; Opapeju, F.O.; Pluske, J.R.; Kim, J.C.; Hampson, D.J.; Nyachoti, C.M. Gastrointestinal health and function in weaned pigs: A review of feeding strategies to control post-weaning diarrhoea without using in-feed antimicrobial compounds. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl.) 2013, 97, 207–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middelkoop, A. Foraging in the Farrowing Room to Stimulate Feeding. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Jang, H.D.; Kim, I.H. Effects of creep feed with varied energy density diets on litter performance. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 24, 1435–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.; Ersbøll, A.K.; Jensen, K.H.; Nielsen, J.P. Escherichia coli post-weaning diarrhoea occurrence in piglets with monitored exposure to creep feed. Vet. Microbiol. 2005, 110, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callesen, J.; Halas, D.; Thorup, F.; Bach Knudsen, K.E.; Kim, J.C.; Mullan, B.P.; Hampson, D.J.; Wilson, R.H.; Pluske, J.R. The effects of weaning age, diet composition, and categorisation of creep feed intake by piglets on diarrhoea and performance after weaning. Livest. Sci. 2007, 108, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedemann, M.S.; Dybkjær, L.; Jensen, B.B. Pre-weaning eating activity and morphological parameters in the small and large intestine of piglets. Livest. Sci. 2007, 108, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meulen, J.; Koopmans, S.J.; Dekker, R.A.; Hoogendoorn, A. Increasing weaning age of piglets from 4 to 7 weeks reduces stress, increases post-weaning feed intake but does not improve intestinal functionality. Animal 2010, 4, 1653–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuller, W.I.; van Beers-Schreurs, H.M.G.; Soede, N.M.; Taverne, M.A.M.; Kemp, B.; Verheijden, J.H.M. Addition of chromic oxide to creep feed as a fecal marker for selection of creep feed-eating suckling pigs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2007, 68, 748–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera, R.A.; Usry, J.L.; Arrellano, C.; Nogueira, E.T.; Kutschenko, M.; Moeser, A.J.; Odle, J. Effects of creep feeding and supplemental glutamine or glutamine plus glutamate (Aminogut) on pre- and post-weaning growth performance and intestinal health of piglets. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2013, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muns, R.; Magowan, E. The effect of creep feed intake and starter diet allowance on piglets’ gut structure and growth performance after weaning. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96, 3815–3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrallardona, D.; Andrés-Elias, N.; López-Soria, S.; Badiola, I.; Cerdà-Cuéllar, M. Effect of feeding different cereal-based diets on the performance and gut health of weaned piglets with or without previous access to creep feed during lactation. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Zhu Wei-yun, W.Y.; Smidt, H.; Verstegen, M.W.A. Cultivation-independent analysis of the development of the lactobacillus spp. community in the intestinal tract of newborn piglets. Agric. Sci. China 2011, 10, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, G.; Ma, S.; Zhu, Z.; Su, Y.; Zoetendal, E.G.; Mackie, R.; Liu, J.; Mu, C.; Huang, R.; Smidt, H.; et al. Age, introduction of solid feed and weaning are more important determinants of gut bacterial succession in piglets than breed and nursing mother as revealed by a reciprocal cross-fostering model. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 1566–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, R. Early-Life Feeding in Piglets: The Impact on Intestinal Microbiota and Mucosal Development. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, L.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Ma, J.; Jin, L.; Chen, L.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, L.; et al. Alterations in cecal microbiota of Jinhua piglets fostered by a Yorkshire sow. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2014, 59, 4304–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevarra, R.B.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Seok, M.J.; Kim, D.W.; Kang, B.N.; Johnson, T.J.; Isaacson, R.E.; Kim, H.B. Piglet gut microbial shifts early in life: Causes and effects. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hees, H.M.J.; Davids, M.; Maes, D.; Millet, S.; Possemiers, S.; den Hartog, L.A.; van Kempen, T.A.T.G.; Janssens, G.P.J. Dietary fibre enrichment of supplemental feed modulates the development of the intestinal tract in suckling piglets. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 10, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huting, A.M.S.; Almond, K.; Wellock, I.; Kyriazakis, I. What is good for small piglets might not be good for big piglets: The consequences of cross-fostering and creep feed provision on performance to slaughter. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 95, 4926–4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, A.L.; Duncan, I.J.H.; Millman, S.T.; Friendship, R.M.; Widowski, T.M. The effect of dentition on feeding development in piglets and on their growth and behavior after weaning. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88, 2277–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huting, A.M.S.; Sakkas, P.; Kyriazakis, I. Sows in mid parity are best foster mothers for the pre- and post-weaning performance of both light and heavy piglets. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 1656–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middelkoop, A.; Costermans, N.; Kemp, B.; Bolhuis, J.E. Feed intake of the sow and playful creep feeding of piglets influence piglet behaviour and performance before and after weaning. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skok, J.; Brus, M.; Škorjanc, D. Growth of piglets in relation to milk intake and anatomical location of mammary glands. Acta Agric. Scand. A Anim. Sci. 2007, 57, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.Z.; Wang, X.Q.; Wu, G.Y.; Kim, S.W.; Chen, F.; Wang, J.J. Differential composition of proteomes in sow colostrum and milk from anterior and posterior mammary glands. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88, 2657–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skok, J.; Prevolnik, M.; Urek, T.; Mesarec, N.; Škorjanc, D. Behavioural patterns established during suckling reappear when piglets are forced to form a new dominance hierarchy. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 161, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algers, B.; Jensen, P.; Steinwall, L. Behaviour and weight changes at weaning and regrouping of pigs in relation to teat quality. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1990, 26, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajor, E.A.; Fraser, D.; Kramer, D.L. Consumption of solid food by suckling pigs: Individual variation and relation to weight gain. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1991, 32, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøe, K.; Jensen, P. Individual differences in suckling and solid food intake by piglets. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1995, 42, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Passillé, A.M.; Pelletier, G.; Ménard, J.; Morisset, J. Relationships of weight gain and behavior to digestive organ weight and enzyme activities in piglets. J. Anim. Sci. 1989, 67, 2921–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, M.C.; Pajor, E.A.; Fraser, D. Individual variation in feeding and growth of piglets: Effects of increased access to creep food. Anim. Prod. 1992, 55, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popowics, T.E.; Herring, S.W. Teeth, jaws and muscles in mammalian mastication. In Feeding in Domestic Vertebrates: From Structure To Behaviour; Bels, V.L., Ed.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, The Netherland, 2006; pp. 61–83. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, A.L.; Widowski, T.M. Normal profiles for deciduous dental eruption in domestic piglets: Effect of sow, litter, and piglet characteristics. J. Anim. Sci. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clouard, C.; Gerrits, W.J.J.; Kemp, B.; Val-Laillet, D.; Bolhuis, J.E. Perinatal exposure to a diet high in saturated fat, refined sugar and cholesterol affects behaviour, growth, and feed intake in weaned piglets. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e154698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edge, H.L.; Dalby, J.A.; Rowlinson, P.; Varley, M.A. The effect of pellet diameter on the performance of young pigs. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2005, 97, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.B.; de Jong, J.A.; DeRouchey, J.M.; Tokach, M.D.; Dritz, S.S.; Goodband, R.D.; Woodworth, J.C. Effects of creep feed pellet diameter on suckling and nursery pig performance. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 49, 100–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Craig, J.R.; Kim, J.C.; Brewster, C.J.; Smits, R.J.; Braden, C.; Pluske, J.R. Increasing creep pellet size improves creep feed disappearance of gilts and sow progeny in lactation and enhances pig production after weaning. J. Swine Health Prod. 2021, 29, 10–18. Available online: https://www.aasv.org/shap/issues/v29n1/v29n (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Yoder, A.D.; Stark, C.R.; Tokach, M.D.; Jones, C.K. Effects of pellet processing parameters on pellet quality and nursery pig growth performance. Trans. ASABE 2019, 62, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wan, M.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, A. Effects of soft pellet creep feed on pre-weaning and post-weaning performance and intestinal development in piglets. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medel, P.; Salado, S.; de Blas, J.C.; Mateos, G.G. Processed cereals in diets for early-weaned piglets. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1999, 82, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokach, M.D.; Cemin, H.S.; Sulabo, R.D.; Goodband, R.D. Feeding the suckling pig: Creep feeding. In The Suckling and Weaned Piglet; Farmer, C., Ed.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 139–157. ISBN 978-90-8686-343-3. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Patience, J.F. Factors involved in the regulation of feed and energy intake of pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2016, 233, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouard, C.; Venrooij, K.; Auge, A.; van Enckevort, A. Effets d’un nouveau type d’aliment maternité sur les performances et le comportement des porcelets avant et après sevrage. Journ. Rech. Porc. 2018, 50, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Fouhse, J.M.; Dawson, K.; Graugnard, D.; Dyck, M.; Willing, B.P. Dietary supplementation of weaned piglets with a yeast-derived mannan-rich fraction modulates cecal microbial profiles, jejunal morphology and gene expression. Animal 2019, 13, 1591–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.B. Effects of Prebiotics, Probiotics and Synbiotics in the Diet of Young Pigs. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, H.; Bundy, J.W.; Hinkle, E.E.; Walter, J.; Burkey, T.E.; Miller, P.S. Effects of a yeast-dried milk product in creep and phase-1 nursery diets on growth performance, circulating immunoglobulin A, and fecal microbiota of nursing and nursery pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 92, 4518–4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zhang, L.; Mu, C.; He, X.; Su, Y.; Mao, S.; Zhang, J.; Smidt, H.; Zhu, W. Effects of dietary fibre source on microbiota composition in the large intestine of suckling piglets. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2016, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, C.; Zhang, L.; He, X.; Smidt, H.; Zhu, W. Dietary fibres modulate the composition and activity of butyrate-producing bacteria in the large intestine of suckling piglets. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2017, 110, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hees, H.; Maes, D.; Millet, S.; den Hartog, L.; van Kempen, T.; Janssens, G. Fibre supplementation to pre-weaning piglet diets did not improve the resilience towards a post-weaning enterotoxigenic E. coli challenge. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl.) 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, P.S.; Kim, D.H.; Jang, J.C.; Hong, J.S.; Kim, Y.Y. Effects of different creep feed types on pre-weaning and post-weaning performance and gut development. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 31, 1956–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middelkoop, A.; van Marwijk, M.A.; Kemp, B.; Bolhuis, J.E. Pigs like it varied; feeding behavior and pre- and post-weaning performance of piglets exposed to dietary diversity and feed hidden in substrate during lactation. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkeveld, M.; Langendijk, P.; van Beers-Schreurs, H.M.G.; Koets, A.P.; Taverne, M.A.M.; Verheijden, J.H.M. Postweaning growth check in pigs is markedly reduced by intermittent suckling and extended lactation. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langendijk, P.; Bolhuis, J.E.; Laurenssen, B.F.A. Effects of pre- and postnatal exposure to garlic and aniseed flavour on pre- and postweaning feed intake in pigs. Livest. Sci. 2007, 108, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, S.L.; Edwards, S.A.; Sutcliffe, E.; Knap, P.W.; Kyriazakis, I. Identification of risk factors associated with poor lifetime growth performance in pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 4123–4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulabo, R.C.; Jacela, J.Y.; Tokach, M.D.; Dritz, S.S.; Goodband, R.D.; Derouchey, J.M.; Nelssen, J.L. Effects of lactation feed intake and creep feeding on sow and piglet performance. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88, 3145–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larriestra, A.J.; Wattanaphansak, S.; Neumann, E.J.; Bradford, J.; Morrison, R.B.; Deen, J. Pig characteristics associated with mortality and light exit weight for the nursery phase. Can. Vet. J. 2006, 47, 560–566. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón Díaz, J.A.; Boyle, L.A.; Diana, A.; Leonard, F.C.; Moriarty, J.P.; McElroy, M.C.; McGettrick, S.; Kelliher, D.; García Manzanilla, E. Early life indicators predict mortality, illness, reduced welfare and carcass characteristics in finisher pigs. Prev. Vet. Med. 2017, 146, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, S.L.; Edwards, S.A.; Kyriazakis, I. Are all piglets born lightweight alike? Morphological measurements as predictors of postnatal performance. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 3510–3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynegaard, J.C.; Hansen, C.F.; Kristensen, A.R.; Amdi, C. Body composition and organ development of intra-uterine growth restricted pigs at weaning. Animal 2020, 14, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuller, W.I.; van Beers-Schreurs, H.M.G.; Soede, N.M.; Langendijk, P.; Taverne, M.A.M.; Kemp, B.; Verheijden, J.H.M. Creep feed intake during lactation enhances net absorption in the small intestine after weaning. Livest. Sci. 2007, 108, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruininx, E.M.A.M.; Binnendijk, G.P.; van der Peet-Schwering, C.M.C.; Schrama, J.W.; den Hartog, L.A.; Everts, H.; Beynen, A.C. Effect of creep feed consumption on individual feed intake characteristics and performance of group-housed weanling pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2002, 80, 1413–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuller, W.I.; Soede, N.M.; van Beers-Schreurs, H.M.G.; Langendijk, P.; Taverne, M.A.M.; Kemp, B.; Verheijden, J.H.M. Effects of intermittent suckling and creep feed intake on pig performance from birth to slaughter. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, B.; Stewart, G.B.; Panzone, L.A.; Kyriazakis, I.; Frewer, L.J. A systematic review of public attitudes, perceptions and behaviours towards production diseases associated with farm animal welfare. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2016, 29, 455–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defra. Sustainable Systems for Weaner Management: AGEWEAN. 2007. Available online: http://randd.defra.gov.uk/Default.aspx?Module=More&Location=None&ProjectID=11660 (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Colson, V.; Orgeur, P.; Foury, A.; Mormède, P. Consequences of weaning piglets at 21 and 28 days on growth, behaviour and hormonal responses. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2006, 98, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leliveld, L.M.C.; Riemensperger, A.V.; Gardiner, G.E.; O’Doherty, J.V.; Lynch, P.B.; Lawlor, P.G. Effect of weaning age and postweaning feeding programme on the growth performance of pigs to 10 weeks of age. Livest. Sci. 2013, 157, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeser, A.J.; Ryan, K.A.; Nighot, P.K.; Blikslager, A.T. Gastrointestinal dysfunction induced by early weaning is attenuated by delayed weaning and mast cell blockade in pigs. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2007, 293, G413–G421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellock, I.J.; Fortomaris, P.D.; Houdijk, J.G.M.; Kyriazakis, I. Effect of weaning age, protein nutrition and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli challenge on the health of newly weaned piglets. Livest. Sci. 2007, 108, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nieuwamerongen, S.E.; Soede, N.M.; van der Peet-Schwering, C.M.C.; Kemp, B.; Bolhuis, J.E. Gradual weaning during an extended lactation period improves performance and behavior of pigs raised in a multi-suckling system. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 194, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, J.; Satyapaul; Chhabra, A.K.; Chandrahas. Effect of early weaning, split-weaning and nursery feeding programmes on the growth of Landrace x Desi pigs. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2004, 36, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huting, A.M.S.; Wellock, I.; Tuer, S.; Kyriazakis, I. Weaning age and post-weaning nursery feeding regime are important in improving the performance of lightweight pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 4834–4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagne, L.; Boundry, G.; Favier, C.; Le Huerou-Luron, I.; Lallès, J.P.; Sève, B. Main intestinal markers associated with the changes in gut architecture and function in piglets after weaning. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 97, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Dividich, J.; Herpin, P. Effects of climatic conditions on the performance, metabolism and health status of weaned piglets: A review. Livest. Prod. Sci. 1994, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.Z.; Pluske, J.R. The low feed intake in newly-weaned pigs: Problems and possible solutions. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 20, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrallardona, D.; Roura, E. Voluntary Feed Intake in Pigs; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2009; ISBN 9789086866892. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, J.-M.; Kim, J.-C.; Hansen, C.F.; Mullan, B.P.; Hampson, D.J.; Pluske, J.R. Effects of feeding low protein diets to piglets on plasma urea nitrogen, faecal ammonia nitrogen, the incidence of diarrhoea and performance after weaning. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 2008, 62, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, P.G.; Gardener, G.E.; Goodband, R.D. Feeding the weaned piglet. In The Suckling and Weaned Piglet; Farmer, C., Ed.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Modina, S.C.; Polito, U.; Rossi, R.; Corino, C.; Di Giancamillo, A. Nutritional regulation of gut barrier integrity in weaning piglets. Animals 2019, 9, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, X.; Tan, B.; Song, M.; Ji, P.; Kim, K.; Yin, Y.; Liu, Y. Nutritional intervention for the intestinal development and health of weaned pigs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lærke, H.N.; Hedemann, M.S. The digestive system of the pig. In Nutritional Physiology of Pigs—Online Publication; Knudsen, K.E.B., Kjeldsen, N.J., Poulsen, H.D., Jensen, B., Eds.; Videncenter for Svineproduktion: Foulum, Denmark, 2012; Available online: https://svineproduktion.dk/-/media/PDF/Services/Undervisningsmateriale/Laerebog_fysiologi/Chapter-5.ashx?la=da&hash=724D1FCA45EFEB9E655157A2C537BDE525DFBF5D (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Mennah-Govela, Y.A.; Singh, R.P.; Bornhorst, G.M. Buffering capacity of protein-based model food systems in the context of gastric digestion. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 6074–6087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cranwell, P.D.; Noakes, D.E.; Hill, K.J. Gastric secretion and fermentation in the suckling pig. Br. J. Nutr. 1976, 36, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruininx, E.M.A.M.; Schellingerhout, A.B.; Binnendijk, G.P.; van der Peet-Schwering, C.M.C.; Schrama, J.W.; den Hartog, L.A.; Everts, H.; Beynen, A.C. Individually assessed creep food consumption by suckled piglets: Influence on post-weaning food intake characteristics and indicators of gut structure and hind-gut fermentation. Anim. Sci. 2004, 78, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warneboldt, F.; Sander, S.J.; Beineke, A.; Valentin-Weigand, P.; Kamphues, J.; Baums, C.G. Clearance of Streptococcus suis in stomach contents of differently fed growing pigs. Pathogens 2016, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, P.G.; Lynch, P.B.; Caffrey, P.J.; O’Reilly, J.J.; O’Connell, M.K. Measurements of the acid-binding capacity of ingredients used in pig diets. Ir. Vet. J. 2005, 58, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giger-Reverdin, S.; Duvaux-Ponter, C.; Sauvant, D.; Martin, O.; Nunes do Prado, I.; Müller, R. Intrinsic buffering capacity of feedstuffs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2002, 96, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Zhan, W.; Boom, R.M.; Janssen, A.E.M. Interactions between acid and proteins under in vitro gastric condition—A theoretical and experimental quantification. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 5283–5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CVB. Tabellenboek Voeding Varkens, 63rd ed.; Stichting CVB: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- González-Vega, J.C.; Liu, Y.; McCann, J.C.; Walk, C.L.; Loor, J.J.; Stein, H.H. Requirement for digestible calcium by eleven- to twenty-five–kilogram pigs as determined by growth performance, bone ash concentration, calcium and phosphorus balances, and expression of genes involved in transport of calcium in intestinal and kidney cell. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 3321–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partanen, K.H.; Mroz, Z. Organic acids for performance enhancement in pig diets. Nutr. Res. Rev. 1999, 12, 117–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suiryanrayna, M.V.A.N.; Ramana, J.V. A review of the effects of dietary organic acids fed to swine. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferronato, G.; Prandini, A. Dietary supplementation of inorganic, organic, and fatty acids in pig: A review. Animals 2020, 10, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisemann, J.H.; van Heugten, E. Response of pigs to dietary inclusion of formic acid and ammonium formate. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 1530–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, L.D.; Fondevila, M.; Lobera, M.B.; Castrillo, C. Effect of combinations of organic acids in weaned pig diets on microbial species of digestive tract contents and their response on digestibility. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl.) 2005, 89, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giesting, D.W.; Roos, M.A.; Easter, R.A. Evaluation of the effect of fumaric acid and sodium bicarbonate addition on performance of starter pigs fed diets of different types. J. Anim. Sci. 1991, 69, 2489–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, E.J.; Wilkinson, S.J.; Cronin, G.M.; Walk, C.L.; Cowieson, A.J. Effects of phytase, calcium source, calcium concentration and particle size on broiler performance, nutrient digestibility and skeletal integrity. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2018, 58, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schop, M.; Jansman, A.J.M.; de Vries, S.; Gerrits, W.J.J. Increasing intake of dietary soluble nutrients affects digesta passage rate in the stomach of growing pigs. Br. J. Nutr. 2019, 121, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fledderus, J.; Bikker, P.; Kluess, J.W. Increasing diet viscosity using carboxymethylcellulose in weaned piglets stimulates protein digestibility. Livest. Sci. 2007, 109, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentle, R.G.; Janssen, P.W.M. Manipulating digestion with foods designed to change the physical characteristics of digesta. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 50, 130–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, E.A.; Badiola, I.; Francesch, M.; Torrallardona, D. Effect of cereal extrusion on performance, nutrient digestibility, and cecal fermentation in weanling pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.H.; Bello-Pérez, L.A.; Lin, A.H.M.; Kim, C.Y.; Hamaker, B.R. Importance of location of digestion and colonic fermentation of starch related to its quality. Cereal Chem. 2013, 90, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svihus, B.; Kløvstad, K.H.; Perez, V.; Zimonja, O.; Sahlström, S.; Schüller, R.B.; Jeksrud, W.K.; Prestløkken, E. Physical and nutritional effects of pelleting of broiler chicken diets made from wheat ground to different coarsenesses by the use of roller mill and hammer mill. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2004, 117, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukmirović, Đ.; Čolović, R.; Rakita, S.; Brlek, T.; Đuragić, O.; Solà-Oriol, D. Importance of feed structure (particle size) and feed form (mash vs. pellets) in pig nutrition—A review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2017, 233, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiarie, E.G.; Mills, A. Role of feed processing on gut health and function in pigs and poultry: Conundrum of optimal particle size and hydrothermal regimens. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedemann, M.S.; Mikkelsen, L.L.; Naughton, P.J.; Jensen, B.B. Effect of feed particle size and feed processing on morphological characteristics in the small and large intestine of pigs and on adhesion of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT12 in the ileum in vitro. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 83, 1554–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molist, F.; Gómez de Segura, A.; Pérez, J.F.; Bhandari, S.K.; Krause, D.O.; Nyachoti, C.M. Effect of wheat bran on the health and performance of weaned pigs challenged with Escherichia coli K88+. Livest. Sci. 2010, 133, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornhorst, G.M.; Chang, L.Q.; Rutherfurd, S.M.; Moughan, P.J.; Singh, R.P. Gastric emptying rate and chyme characteristics for cooked brown and white rice meals in vivo. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 2900–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, O.J.; Stein, H.H. Processing of ingredients and diets and effects on nutritional value for pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, D.A.; Lee, S.A.; Jones, C.K.; Htoo, J.K.; Stein, H.H. Digestibility of amino acids, fiber, and energy by growing pigs, and concentrations of digestible and metabolizable energy in yellow dent corn, hard red winter wheat, and sorghum may be influenced by extrusion. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020, 268, 114602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, A.R.; Luo, H.F.; Wei, H.; Zhou, Z.; Peng, J.; Ru, Y.J. In Vitro and In Vivo digestibility of corn starch for weaned pigs: Effects of amylose: Amylopectin ratio, extrusion, storage duration, and enzyme supplementation. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 93, 3512–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, M.R.; Classen, H.L. An in vitro assay for prediction of broiler intestinal viscosity and growth when fed rye-based diets in the presence of exogenous enzymes. Poult. Sci. 1993, 72, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martens, B.M.J.; Flécher, T.; de Vries, S.; Schols, H.A.; Bruininx, E.M.A.M.; Gerrits, W.J.J. Starch digestion kinetics and mechanisms of hydrolysing enzymes in growing pigs fed processed and native cereal-based diets. Br. J. Nutr. 2019, 121, 1124–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopwood, D.E.; Pethick, D.W.; Pluske, J.R.; Hampson, D.J. Addition of pearl barley to a rice-based diet for newly weaned piglets increases the viscosity of the intestinal contents, reduces starch digestibility and exacerbates post-weaning colibacillosis. Br. J. Nutr. 2004, 92, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Asiedu, A.; Patience, J.F.; Laarveld, B.; van Kessel, A.G.; Simmins, P.H.; Zijlstra, R.T. Effects of guar gum and cellulose on digesta passage rate, ileal microbial populations, energy and protein digestibility, and performance of grower pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 84, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyekum, A.K.; Nyachoti, C.M. Nutritional and metabolic consequences of feeding high-fiber diets to swine: A review. Engineering 2017, 3, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canibe, N.; Bach Knudsen, K.E. Degradation and physicochemical changes of barley and pea fibre along the gastrointestinal tract of pigs. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2002, 82, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Theil, P.K.; Wu, D.; Knudsen, K.E.B. In vitro digestion methods to characterize the physicochemical properties of diets varying in dietary fibre source and content. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2018, 235, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauson, A. Feed intake and energy supply growing pigs. In Nutritional Physiology of Pigs: With Emphasis on Danish Production Conditions; Landbrug & Fødevare: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012; Available online: https://curis.ku.dk/ws/files/40849708/Chapter_19.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Black, J.L.; Williams, B.A.; Gidley, M.J. Metabolic Regulation of Feed Intake in Monogastric Mammals; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2009; ISBN 9789086860968. [Google Scholar]

- Ndou, S.P.; Gous, R.M.; Chimonyo, M. Prediction of scaled feed intake in weaner pigs using physico-chemical properties of fibrous feeds. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 110, 774–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyachoti, C.M.; Arntfield, S.D.; Guenter, W.; Cenkowski, S.; Opapeju, F.O. Effect of micronized pea and enzyme supplementation on nutrient utilization and manure output in growing pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 84, 2150–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynegaard, J.C.; Kjeldsen, N.J.; Bache, J.K.; Weber, N.R.; Hansen, C.F.; Nielsen, J.P.; Amdi, C. Low protein diets without medicinal zinc oxide for weaned pigs reduced diarrhoea treatments and average daily gain. Animal 2021, 15, 100075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, R.; Berrocoso, J.F.D. Dietary fiber and protein fermentation in the intestine of swine and their interactive effects on gut health and on the environment: A review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2016, 212, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, C.A.; Cabrera, D.L.; Zou, M.; Boland, M.J.; Moughan, P.J. The rate at which digested protein enters the small intestine modulates the rate of amino acid digestibility throughout the small intestine of growing pigs. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 1743–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H. Protein Digestion Kinetics in Pigs and Poultry. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fastinger, N.D.; Mahan, D.C. Effect of soybean meal particle size on amino acid and energy digestibility in grower-finisher swine. J. Anim. Sci. 2003, 81, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, D.G.; Serrano, M.P.; Lázaro, R.; Latorre, M.A.; Mateos, G.G. Influence of micronization (fine grinding) of soya bean meal and fullfat soya bean on productive performance and digestive traits in young pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2008, 147, 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, M.E.E.; Magowan, E.; McCracken, K.J.; Beattie, V.E.; Bradford, R.; Thompson, A.; Gordon, F.J. An investigation into the effect of dietary particle size and pelleting of diets for finishing pigs. Livest. Sci. 2015, 173, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, S.; Aluwé, M.; van den Broeke, A.; Leen, F.; de Boever, J.; de Campeneere, S. Review: Pork production with maximal nitrogen efficiency. Animal 2018, 12, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klasing, K.C. Minimizing amino acid catabolism decreases amino acid requirements. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mou, Q.; Yang, H.S.; Yin, Y.L.; Huang, P.F. Amino acids influencing intestinal development and health of the piglets. Animals 2019, 9, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molist, F.; van Oostrum, M.; Pérez, J.F.; Mateos, G.; Nyachoti, C.M.; van der Aar, P.J. Relevance of functional properties of dietary fibre in diets for weanling pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2014, 189, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flis, M.; Sobotka, W.; Antoszkiewicz, Z. Fiber substrates in the nutrition of weaned piglets—A review. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2017, 17, 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagne, L.; Le Floc’h, N.; Arturo-Schaan, M.; Foret, R.; Urdaci, M.C.; Le Gall, M. Comparative effects of level of dietary fiber and sanitary conditions on the growth and health of weanling pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90, 2556–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, R.; van der Aar, P.; Molist, F. Insoluble nonstarch polysaccharides in diets for weaned piglets. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90, 318–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Yin, J.; Xu, K.; Li, T.; Yin, Y. What is the impact of diet on nutritional diarrhea associated with gut microbiota in weaning piglets: A system review. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 6916189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, X.; Li, D. Fat nutrition and metabolism in piglets: A review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2003, 109, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decuypere, J.A.; Dierick, N.A. The combined use of triacylglycerols containing medium-chain fatty acids and exogenous lipolytic enzymes as an alternative to in-feed antibiotics in piglets: Concept, possibilities and limitations. An overview. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2003, 16, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackman, J.A.; Boyd, R.D.; Elrod, C.C. Medium-chain fatty acids and monoglycerides as feed additives for pig production: Towards gut health improvement and feed pathogen mitigation. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Brendemuhl, J.H.; Jeong, K.C.; Badinga, L. Effects of dietary omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on growth and immune response of weanling pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2014, 24, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, L.A.; Hooda, S.; Fisher-Heffernan, R.E.; Karrow, N.A.; de Lange, C.F.M. Effect of reducing the ratio of omega-6-to-omega-3 fatty acids in diets of low protein quality on nursery pig growth performance and immune response. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96, 4348–4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, T.K.; Yi, Y.J.; Kim, J.C.; Pluske, J.R.; Cho, H.M.; Wickramasuriya, S.S.; Kim, E.; Lee, S.M.; Heo, J.M. Reducing the dietary omega-6 to omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid ratio attenuated inflammatory indices and sustained epithelial tight junction integrity in weaner pigs housed in a poor sanitation condition. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2017, 234, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijtten, P.J.A.; van der Meulen, J.; Verstegen, M.W.A. Intestinal barrier function and absorption in pigs after weaning: A review. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 105, 967–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayaraman, B.; Nyachoti, C.M. Husbandry practices and gut health outcomes in weaned piglets: A review. Anim. Nutr. 2017, 3, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhouma, M.; Fairbrother, J.M.; Beaudry, F.; Letellier, A. Post weaning diarrhea in pigs: Risk factors and non-colistin-based control strategies. Acta Vet. Scand. 2017, 59, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nørgaard, J.V. Age dependent digestibility and absorption profiles of protein feedstuffs for piglets. In Proceedings of the WIAS Symposium Nutrient Digestion and Feed Intake in Pigs, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 29 January 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kahindi, R.K.; Htoo, J.K.; Nyachoti, C.M. Dietary lysine requirement for 7–16 kg pigs fed wheat-corn-soybean meal-based diets. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl.) 2017, 101, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, D.C.; Gaines, A.M.; Allee, G.L.; Usry, J.L. Commercial validation of the true ileal digestible lysine requirement for eleven- to twenty-seven-kilogram pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 82, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikker, P.; van Baal, J.; Binnendijk, G.P.; van Diepen, J.T.M.; Troquet, L.M.P.; Jongbloed, A.W. Copper in Diets for Weaned Pigs; Influence of Level and Duration of Copper Supplementation; Wageningen UR Livestock Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2015; Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/336471 (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Chen, T.; Chen, D.; Tian, G.; Zheng, P.; Mao, X.; Yu, J.; He, J.; Huang, Z.; Luo, Y.; Luo, J.; et al. Effects of soluble and insoluble dietary fiber supplementation on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, intestinal microbe and barrier function in weaning piglet. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020, 260, 114335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, R.G.; Molist, F.; Ywazaki, M.; Nofrarías, M.; Gomez de Segura, A.; Gasa, J.; Pérez, J.F. Effect of dietary level of protein and fiber on the productive performance and health status of piglets. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 87, 3569–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Fiz, F.; Neila-Ibáñez, C.; López-Soria, S.; Napp, S.; Martinez, B.; Sobrevia, L.; Tibble, S.; Aragon, V.; Migura-Garcia, L. Feed additives for the control of post-weaning Streptococcus suis disease and the effect on the faecal and nasal microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, R.C. Dietary fat preference and effects on performance of piglets at weaning. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 30, 834–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference | Dietary Intervention(s) 1 | Intervention Period (Age) | Age at Sampling | Effects on Gut Development versus a Control Oral Gavage with Water or Physiological Saline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [41] | L-glutamine; L-alanyl-L-glutamine: 0.5 g/kg BW twice daily | 7–16 | 16 | ↑ Small-intestine weight, jejunum villus height (after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge) |

| [42] | Inulin: 0.5 to 2 g; Inulin: 0.75 to 3 g | 1–28 | 28 | Positive effect on gut morphology of the small intestine and a reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines at mRNA level in the large intestine. The low inulin level was more beneficial, as it also increased the concentrations of propionate and iso-butyrate in the large intestine. |

| [43] | Inulin: 0.114 g/kg BW; Inulin + Lactobacillus acidophilus W37: 5 × 109 CFU/piglet | 2–23 | 23 | ↑ Health status = Composition and diversity of faecal microbiota |

| [44] | Fructo-oligosaccharides: 10g | 2–14 | 14, 25 | Bifidogenic effect in the colon, changes in mucosal gene-expression profiles in the jejunum relating to intestinal barrier function and immunity (d14 and d25) |

| [45] | Galacto-oligosaccharides: 1 g/kg BW | 0–7 | 8, 21 | Improves the jejunum barrier function: ↑ Small-intestine length at d8 ↓ Crypt depth at d21 ↑ mRNA expression of jejunal growth factors (d8 and d21) ↑ Protein expression of jejunal growth factors (d8) and tight junctions (d8 and d21) ↑ mRNA expression of jejunal nutrient transporters (d21) ↑ mRNA expression of cytokine TGF-β at d8, ↓ mRNA expression of cytokine IL-12 at d8 ↑ Jejunal lactase activity on d8, maltase activity and sucrase activity on d21 |

| [46] | Galacto-oligosaccharides + milk fat globule membrane + fructo-oligosaccharides: 1.2 g/kg BW | 1–7 | 8, 21 | Modulated the gut microbiota in faeces and improved the intestinal barrier function: ↓ α-diversity at d8 (Sobbs index, but not Shannon index) ↑ α-diversity at d21 (Sobbs and Shannon index) ↑ Lactobacillus (d8), Muribaculaceae, Christensenellaceae, Enterococcus and Romboutsia (d21) ↓ Lachnospiraceae (d8), Eubacterium (coprostanoligenes group, d21) ↑ Acetate and propionate (ileum), acetate (colon) ↑ Gene expression of short-chain fatty acid receptors (ileum, colon) ↑ Gene expressions of tight junctions, mucins and cytokines ↓ Plasma diamine oxidase (d21) |

| [47] | β-glucans: 50 to 200 mg every other day | 2–27 | 27 | Modest modulation of the gut microbiota in faeces and immune system: ↓ Shannon diversity in faeces (d4, 8, 14, 26), no differences in jejunum, ileum and caecum digesta ↓ Methanobrevibacter (d8, 14) ↑ Fusobacterium and Ruminococcaceae (several time-points) ↓ Proliferating NK immune cells and γδ T cells in blood at d26 ↑ IL-10 cytokine production by mesenteric lymph node cells (ex vivo) |

| Reference | Dietary Intervention(s) | Intervention Period (Age) | Age at Sampling | Effects on Gut Development Versus Control Creep Feed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [111] | Oligofructose: 0.2%; Probiotics: 0.3%; or their combination as synbiotic | 7–21 | 21 | Modulates gut morphology, as well as gut microbial population in small and large intestine: = Villus height (duodenum, ileum), crypt depth (ileum) ↑ Duodenum crypt depth (only when fed oligofructose) ↑ Bifidobacteria in ileum (also in colon for probiotic products) ↓ Total coliform in colon = Haematological blood parameters |

| [77] | Glutamine: 1%; Glutamine + glutamate: 0.88% | 21–28 (weaning at Day 28) | 35 | = Small-intestine histology and absorptive capacity |

| [112] | Yeast-dried milk: 10% | 7–21 | 7, 14, 21 | = Lactobacillus = Serum IgA |

| [110] | Yeast-derived mannan-rich fraction: 800 mg/kg | 7–21 (weaning at Day 21) | 28, 42 | Improves jejunal morphology and alters caecal microbial population at d28, but not at d42: ↑ Jejunal villus height ↑ Gene expression involved in intestinal development, function and immunity ↑ Paraprevotellaceae genera YRC22 and CF231 ↓ Sutterella, Prevotella |

| [113] | Alfalfa: 1.3%; Wheat bran: 2.92%; Cellulose: 1% | 7–22 | 23 | Modulates the gut microbial population in the large intestine:

|

| [114] 1 | Alfalfa: 1.3%; Wheat bran: 2.92%; Cellulose: 1% | 7–22 | 23 | Modulates the abundance and activity of butyrate-producing bacteria in the large intestine:

|

| [85] | Long-chain arabinoxylan: 2%; Cellulose: 5% | 2–24 2 | 23, 24 | = Stomach size, small-intestine permeability

|

| Feedstuff | Body Weight (kg) | Location along the SI | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI 1 | SI 2 | SI 3 | SI 4 | |||

| Ground barley | 33 | 34 | 54 | 86 | 94 | [178] 2 |

| Extruded barley | 33 | 53 | 64 | 94 | 98 | [178] 2 |

| Ground maize | 33 | 21 | 60 | 80 | 84 | [178] 2 |

| Extruded maize | 33 | 53 | 78 | 94 | 98 | [178] 2 |

| Rice, raw | 12 | - | 85.3 | - | 97.1 | [166] 3 |

| Rice, extruded | 12 | - | 83.1 | - | 99.0 | [166] 3 |

| Barley, raw | 12 | - | 80.0 | - | 96.2 | [166] 3 |

| Barley, extruded | 12 | - | 88.5 | - | 98.3 | [166] 3 |

| Low | Medium | High | Very High | LSD 2 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0–14 | ||||||

| ADG (g/d) | 219 ab | 203 a | 240 b | 250 b | 32.81 | 0.033 |

| ADFI (g/d) | 298 | 276 | 305 | 288 | 30.46 | 0.228 |

| FCR | 1.37 c | 1.37 bc | 1.27 b | 1.16 a | 0.097 | <0.001 |

| Faecal score 3 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 0.531 | 0.873 |

| Day 14–28 | ||||||

| ADG (g/d) | 473 a | 524 ab | 525 ab | 572 b | 54.42 | 0.013 |

| ADFI (g/d) | 754 | 782 | 758 | 747 | 56.30 | 0.578 |

| FCR | 1.59 c | 1.49 b | 1.45 b | 1.31 a | 0.075 | <0.001 |

| Faecal score 3 | 6.1 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.9 | 0.603 | 0.315 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huting, A.M.S.; Middelkoop, A.; Guan, X.; Molist, F. Using Nutritional Strategies to Shape the Gastro-Intestinal Tracts of Suckling and Weaned Piglets. Animals 2021, 11, 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11020402

Huting AMS, Middelkoop A, Guan X, Molist F. Using Nutritional Strategies to Shape the Gastro-Intestinal Tracts of Suckling and Weaned Piglets. Animals. 2021; 11(2):402. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11020402

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuting, Anne M.S., Anouschka Middelkoop, Xiaonan Guan, and Francesc Molist. 2021. "Using Nutritional Strategies to Shape the Gastro-Intestinal Tracts of Suckling and Weaned Piglets" Animals 11, no. 2: 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11020402

APA StyleHuting, A. M. S., Middelkoop, A., Guan, X., & Molist, F. (2021). Using Nutritional Strategies to Shape the Gastro-Intestinal Tracts of Suckling and Weaned Piglets. Animals, 11(2), 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11020402