Close Companions? A Zooarchaeological Study of the Human–Cattle Relationship in Medieval England

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How were cattle used in medieval England, and how did this change through time?

- What do historical documents imply regarding the value, use of, and attitudes towards cattle in medieval England?

- Can ethnographic studies of comparable human–animal relationships aid the understanding of how people and cattle co-existed in medieval England?

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Zooarchaeology of the Medieval Economy

3.2. Historical and Ethnographic Sources for the Economic and Social Value of Cattle

“I saw a simple man hanging on a plow. His ragged coat was made of coarse material and his hood was full of holes so that his hair stuck out. His shoes were thickly patched and his toes stuck out as he worked. His stockings hung over the back of his shoes on all sides, and he was spattered with mud as he followed the plow. His mittens were made of rags and the fingers were worn out and covered with mud. He sank in the fen almost to his ankles as he drove four feeble oxen that were so pitiful their ribs could be counted. His wife walked with him, carrying a long goad. Her short coat was torn, and she was wrapped in a winding [winnowing] sheet for protection from the weather. Blood flowed on the ice from her bare feet.”[77] (lines 421–436)

3.3. Historical and Ethnographic Sources for Human–Cattle Relationships

3.4. Integration: Towards an Account of Changing Human–Cattle Relationships

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fowler, P. Farming in the First Millennium AD; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby, S.H. Urban population in late medieval England: The evidence of the lay subsidies. Econ. Hist. Rev. 2010, 63, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, P. Sheep, horses, swine, and kine: A zooarchaeological perspective on the anglo-saxon settlement of England. J. Field Archaeol. 1989, 16, 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree, P.J. Agricultural innovation and socio-economic change in early medieval Europe: Evidence from Britain and France. World Archaeol. 2010, 42, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, M. Animals in Saxon and Scandinavian England: Backbones of Economy and Society; Sidestone: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, T. Livestock and deadstock in early medieval Europe from the North Sea to the Baltic. Environ. Archaeol. 2010, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dyer, C. The economy and society. In The Oxford Illustrated History of Medieval England; Saul, N., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997; pp. 137–173. [Google Scholar]

- Banham, D.; Faith, R. Anglo-Saxon Farms and Farming; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, C. Making a Living in the Middle Ages: The People of Britain 850–1520; Penguin: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Albarella, U. A Review of Animal Bone Evidence from Central England; Historic England: Portsmouth, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, M. Southern England: A Review of Animal Remains from Saxon, Medieval and Post Medieval Archaeological Sites; Historic England Research Report: Portsmouth, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes, N. The Norman Conquest: A Zooarchaeological Perspective; British Archaeological Reports International Series: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, M. The Mouldboard Plough. In FeedSax; Hamerow, H., Ed.; Unpublished Work.

- Bartosiewicz, L.; Van Neer, W.; Lentacker, A. Draught Cattle: Their Osteological Identification and History; Musee Royal de L’Afrique Centrale Tervuren: Tervuren, Belgique; Annales Sciences Zoologiques: Brussels, Belgium, 1997. [Google Scholar]

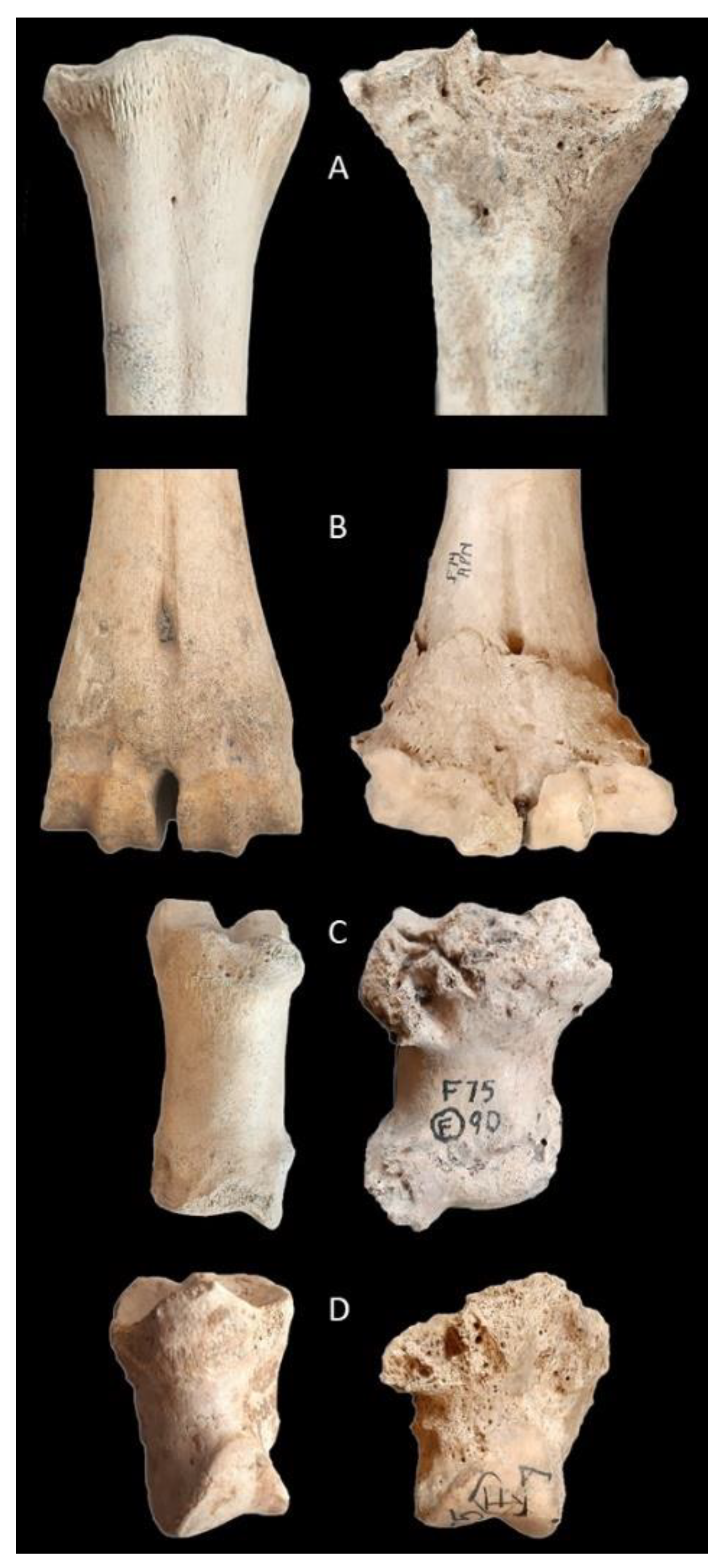

- Thomas, R.; Bellis, L.; Gordon, R.; Holmes, M.; Johannsen, N.; Mahoney, M.; Smith, D. Refining the methods for identifying draught cattle in the archaeological record: Lessons from the semi-feral herd at Chillingham Park. Int. J. Paleopathol. 2021, 33, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fijn, N. Living with Herds: Human-Animal Coexistence in Mongolia; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dubosson, J. Human ‘self’ and animal ‘other’. The favourite animal among the Hamar. In Ethiopian Images of Self and Other; Girke, F., Ed.; Universitätsverlag Halle-Wittenberg: Halle an der Saale, Germany, 2014; pp. 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, P. Multispecies ethnography. In The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology; Callan, H., Ed.; John Wiley and Sons: London, UK, 2018; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, T. The perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, N. Social Zooarchaeology: Humans and Animals in Prehistory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, B. Archaeology and human–animal relations: Thinking through anthropocentrism. Ann. Rev. Anthropol. 2017, 46, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, N. Beastly Questions: Animal Answers to Archaeological Issues; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pluskowski, A. Breaking and Shaping Beastly Bodies; Oxbow: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, F. The decline of the cow: Agricultural and settlement change in early medieval Ireland. Peritia 2008, 20, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullin, M. Animals and anthropology. Soc. Anim. 2002, 10, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oma, K.A. Between trust and domination: Social contracts between humans and animals. World Archaeol. 2010, 42, 175–187. [Google Scholar]

- Hurn, S. Humans and Other Animals; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M. Animals in Celtic Life and Myth; Routledge: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Walker-Meikle, K. Medieval Cats; British Library: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, R. Perceptions versus reality: Changing attitudes towards pets in medieval and post-medieval England. In Just Skin and Bones?: New Perspectives on Human-Animal Relations in the Historical Past; Pluskowski, A., Ed.; British Archaeological Reports International Series: Oxford, UK, 2005; Volume 1410, pp. 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Hamerow, H.; Bogaard, A.; Charles, M.; Forster, E.; Holmes, M.; McKerracher, M.; Neil, S.; Ramsey, C.B.; Stroud, E.; Thomas, R. An integrated bioarchaeological approach to the medieval ‘agricultural revolution’: A case study from Stafford, England, c. AD 800–1200. Eur. J. Archaeol. 2020, 23, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamerow, H.; Bogaard, A.; Charles, M.; Ramsey, C.B.; Thomas, R.; Forster, E.; Holmes, M.; McKerracher, M.; Neil, S.; Stroud, E. Feeding Anglo-Saxon England: The bioarchaeology of an agricultural revolution. Antiquity 2019, 93, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKerracher, M.; Charles, M.; Bronk Ramsey, C.; Hodgson, J.; Hamerow, H.; Zerl, T.; Stroud, E.; Neil, S.; Bogaard, A.; Thomas, R.; et al. Feeding Anglo-Saxon England (FeedSax): The Bioarchaeology of an Agricultural Revolution [Data-Set]; Archaeology Data Service: York, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A. The use of toothwear as a guide to the age of domestic ungulates. In Ageing and Sexing Animal Bones from Archaeological Sites; Wilson, B., Grigson, C., Payne, S., Eds.; British Archaeological Reports British Series: Oxford, UK, 1982; Volume 109, pp. 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, S. Kill-off patterns in sheep and goats: The mandibles from Asvan Kale. Anatol. Stud. 1973, 23, 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, N.; Symmons, R. Sexing cattle horn-cores: Problems and progress. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2007, 17, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, H. Sexing fragmentary ungulate acetabulae. In Recent Advances in Ageing and Sexing Animal Bones; Ruscillo, D., Ed.; Oxbow: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 68–86. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, S.J.; Svensson, E.M.; Albarella, U.; Detry, C.; Gotherstrom, A.; Pires, A.E.; Ginja, C. Molecular and osteometric sexing of cattle metacarpals: A case study from 15th century AD Beja, Portugal. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2012, 39, 1445–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson Dietmeier, J.K. The oxen of Oxon Hill Manor: Pathological analyses and cattle husbandry in eighteenth-century Maryland. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2018, 28, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, M.; Thomas, R.; Hamerow, H. Identifying draught cattle in the past: Lessons from large-scale analysis of archaeological datasets. Int. J. Paleopathol. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Curth, L.H. The Care of Brute Beasts: A Social and Cultural Study of Veterinary Medicine in Early Modern England; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Swabe, J. Animals, Disease and Human Society: Human-Animal Relations and the Rise of Veterinary Medicine; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, W.B. A Medieval Book of Beasts: The Second-Family Bestiary: Commentary, Art, Text and Translation; Boydell Press: Woodbridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Trow-Smith, R. A History of British Livestock Husbandry to 1700; Routledge and Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Kadima, K.; Sackey, A.; Esievo, K. Potential impact of husbandry practices on the welfare and productivity of draught cattle in rural communities around Zaria, Nigeria. Niger. Vet. J. 2017, 38, 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy, N. Draught animal power–socio-economic factors. In Draught Animal Power for Production; Copland, J., Ed.; Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research: Canberra, Australia, 1985; Volume 10, pp. 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy, N. Draught animals and welfare. Rev. Sci. Tech. l’Office Int. Epizoot. 1994, 13, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTavish, C. Making Milking Bodies in the Manawatu: Assembling “Good Cow”-“Good Farmer” Relationships in Productionist Dairy Farming. Master’s Thesis, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Loker, W. The human ecology of cattle raising in the Peruvian Amazon: The view from the farm. Hum. Organ. 1993, 52, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convery, I.; Bailey, C.; Mort, M.; Baxter, J. Death in the wrong place? Emotional geographies of the UK 2001 foot and mouth disease epidemic. J. Rural Stud. 2005, 21, 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Johannsen, N. Past and present strategies for draught exploitation of cattle. In Ethnozooarchaeology; Albarella, U., Trentacoste, A., Eds.; Oxbow: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilakis, Y. Archaeological ethnography: A multitemporal meeting ground for archaeology and anthropology. Ann. Rev. Anthropol. 2011, 40, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilakis, Y.; Anagnostopoulos, A. What is archaeological ethnography? Public Archaeol. 2009, 8, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselain, O.P. To hell with ethnoarchaeology! Archaeol. Dialogues 2016, 23, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarella, U.; Trentacoste, A. Ethnozooarchaeology: The Present and Past of Human-Animal Relationships; Oxbow: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Langdon, J. Horses, Oxen and Technological Innovation: The Use of Draught Animals in English Farming From 1066 to 1500; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Albarella, U. Size, power, wool and veal: Zooarchaeological evidence for late medieval innovations. In Environment and Subsistence in Medieval Europe; De Boe, G., Verhaeghe, F., Eds.; Institute for the Archaeological Heritage of Flanders: Brugge, Belgique, 1997; Volume 9, pp. 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes, N. From cu and sceap to beffe and motton: The management, distribution and consumption of cattle and sheep in Medieval England. In Food in Medieval England: Diet and Nutrition; Woolgar, C., Serjeantson, D., Waldron, T., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 56–71. [Google Scholar]

- Starkey, P. The history of working animals in Africa. In The Origins and Development of African Livestock: Archaeology, Genetics, Linguistics and Ethnography; Blench, R.M., MacDonald, K.C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2000; pp. 478–502. [Google Scholar]

- Whitelock, D. English Historical Documents c.500–1042; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bartosiewicz, L.; Gál, E. Shuffling Nags, Lame Ducks: The Archaeology of Animal Disease; Oxbow: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, G. History of Money; University of Wales Press: Cardiff, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Davidko, N.V. The figurative history of money: Cognitive foundations of money names in Anglo-Saxon. Stud. Lang. 2017, 30, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dendle, P. Textual transmission of the Old English “Loss of Cattle” charm. J. Engl. Ger. Philol. 2006, 105, 514–539. [Google Scholar]

- Hines, J.A. Units of account in gold and silver in seventh-century England: Scillingas, sceattas and pæningas. Antiquaries 2010, 90, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jenkins, D. Law of Hywel Dda: Law Texts of Medieval Wales; Gomer Press: Llandysul, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Astill, G. Overview: Trade, exchange, and urbanization. In The Oxford Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology; Hamerow, H., Hinton, D.A., Crawford, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 503–514. [Google Scholar]

- Lamond, E. Walter of Henley’s Husbandry-Together with an Anonymous Husbandry, Seneschaucie, and Robert Grosseteste’s Rules; Longmans, Green and Co.: London, UK, 1890. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P.; Nice, R.; Wacquant, L. Making the economic habitus: Algerian workers revisited. Ethnography 2000, 1, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodrick, D.O. Symbol and sustenance: Cattle in South Asian culture. Dialect. Anthropol. 2005, 29, 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, D.C.; Rothwell, H. English Historical Documents, 1189–1327; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Grasseni, C. Video and ethnographic knowledge: Skilled vision in the practice of breeding. In Working Images: Visual Research and Representation in Ethnography; Pink, S., Kurti, L., Afonso, I., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 12–27. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, K. Home and heart, hand and eye: Unseen links between pigmen and pigs in industrial farming. In Why We Eat, How We Eat: Contemporary Encounters Between Foods and Bodies; Lavis, A., Abbots, E.-J., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2013; pp. 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Eikestam, L. Remember Me by My Goat: Stories of Relatedness in More-than-Human Worlds of Maasai Women in Kenya. Master’s Thesis, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Greece, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, B. English Historical Documents, 1042–1189; Routledge: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Langdon, J. The economics of horses and oxen in medieval England. Agric. Hist. Rev. 1982, 30, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce the Plowman’s Creed. Available online: https://www.sfsu.edu/~medieval/complaintlit/plowman_creed.html (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Swanton, M. Anglo-Saxon Prose; J.M. Dent: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, G.; McDonnell, G.; Merkel, J.; Marshall, P. Technology, ritual and Anglo-Saxon agriculture: The biography of a plough coulter from Lyminge, Kent. Antiquity 2016, 90, 742–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Standley, E.R. Love and hope: Emotions, dress accessories and a plough in later medieval Britain, c. AD 1250–1500. Antiquity 2020, 94, 742–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, M. The animal bones from Ketton. Unpublished Report for MoLA Northampton, Unpublished Work. 2018; KCC98. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie, R. Livestock/Deadstock: Working with Farm Animals from Birth to Slaughter; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, P.J. Where Have All the Mares Gone? Sex and “Gender” Related Pathology in Archaeological Horses: Clues to Horse Husbandry and Use Practices. In Care or Neglect?: Evidence of Animal Disease in Archaeology; Bartosiewicz, L., Gal, E., Eds.; Oxbow: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 155–174. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, R. Mediaeval Lore from Bartholomew Anglicus; Aeterna Press: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rieth, F.M.S.; Lima, D.V.; Kosby, M.F. The way of life of the Brazilian pampas: An ethnography of the Campoeiros and their animals. Vibrant 2016, 13, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryan, K.; Crabtree, P. The Symbolic Role of Animals in Archaeology; Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Field, J. English Field-Names: A Dictionary; Alan Sutton: Gloucester, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, K. English Place-Names; Batsford: London, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Greatorex, V. Why do Field-Names Matter? An Introduction to Field-Name Elements and Typology. In Field-Names in Cheshire, Shropshire and North-East Wales: Recent Work by Members of Chester Society for Landscape History, 2nd ed.; Greatorex, V., Headon, M., Eds.; Marlston Books: Cheshire, UK, 2014; pp. 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Abbink, J. Love and death of cattle: The paradox in Suri attitudes toward livestock. J. Anthropol. Mus. Ethnogr. 2003, 68, 341–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hovorka, A.J. Women/chickens vs. men/cattle: Insights on gender–species intersectionality. Geoforum 2012, 43, 875–884. [Google Scholar]

- Lucy, S. Gender and gender roles. In The Oxford Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology; Hamerow, H., Hinton, D.A., Crawford, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 688–703. [Google Scholar]

- Leyser, H. Medieval Women, 2nd ed.; Phoenix Press: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Flintan, F. Women’s Empowerment in Pastoral Societies; International Union for Conservation of Nature: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K. Man and the Natural World: Changing Attitudes in England 1500–1800; Penguin: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, M. Beyond food: Placing animals in the framework of social change in post-Roman England. Archaeol. J. 2018, 175, 184–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, N. Deer, land, knives and halls: Social change in early medieval England. Antiqu. J. 2010, 90, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullin, M.H. Mirrors and windows: Sociocultural studies of human-animal relationships. Ann. Rev. Anthropol. 1999, 28, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekar, C.T.; Reed, C.G. Land markets and inequality: Evidence from medieval England. Eur. Rev.Econ. Hist. 2013, 17, 294–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coss, P.R. An age of deference. In A Social History of England, 1200–1500; Horrox, R., Ormrod, W.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 31–73. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, E.; Hatcher, J. Medieval England: Rural Society and Economic Change 1086-1348; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Steel, K. How to Make a Human: Animals and Violence in the Middle Ages; The Ohio State University Press: Columbus, OH, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Overton, N.; Hamilakis, Y. A manifesto for a social zooarchaeology: Swans and other beings in the Mesolithic. Archaeol. Dialogues 2013, 20, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site Type | AD 450–650 | AD 650–850 | AD 850–1066 | AD 1066–1250 | AD 1250–1400 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ecclesiastical | 6 | 5 | 14 | 6 | |

| High-Status | 2 | 9 | 9 | 52 | 18 |

| Rural | 53 | 36 | 15 | 32 | 17 |

| Urban | 5 | 30 | 83 | 129 | 61 |

| Total | 60 | 81 | 112 | 227 | 102 |

| Site | County | Phase (Years AD) | No. Bones |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barking Abbey | London | 500–850 | 2 |

| 675–850 | 3 | ||

| 850–1066 | 1 | ||

| 1066–1200 | 12 | ||

| 1200–1400 | 3 | ||

| Bow Street | London | 600–750 | 54 |

| Collingbourne | Wiltshire | 700–900 | 13 |

| Cook Street | Southampton | 650–875 | 111 |

| Eynsham | Oxfordshire | 500–650 | 14 |

| 650–850 | 144 | ||

| 850–1066 | 12 | ||

| 1066–1300 | 187 | ||

| 1200–1330 | 44 | ||

| Flaxengate | Lincoln | 870–1090 | 184 |

| 1060–1200 | 224 | ||

| 1200–1400 | 73 | ||

| French Quarter | Southampton | 900–1066 | 99 |

| 1066–1250 | 105 | ||

| 1250–1350 | 107 | ||

| Ketton | Northamptonshire | 850–1066 | 11 |

| Lyminge | Kent | 400–700 | 86 |

| 600–850 | 142 | ||

| 1100–1300 | 15 | ||

| Market Lavington | Wiltshire | 400–700 | 163 |

| 700–900 | 2 | ||

| 900–1175 | 0 | ||

| 1100–1300 | 5 | ||

| 1300–1400 | 2 | ||

| Quarrington | Lincolnshire | 450–650 | 41 |

| 650–900 | 37 | ||

| Ramsbury | Wiltshire | 750–850 | 45 |

| 800–1300 | 3 | ||

| Sedgeford | Norfolk | 650–875 | 43 |

| 800–1025 | 95 | ||

| Stafford | Staffordshire | 900–1100 | 2 |

| 1100–1300 | 46 | ||

| Stoke Quay | Suffolk | 700–875 | 163 |

| 825–1100 | 55 | ||

| 1050–1200 | 89 | ||

| 1150–1400 | 42 | ||

| Stratton | Bedfordshire | 400–600 | 16 |

| 600–850 | 42 | ||

| 850–1150 | 54 | ||

| 1150–1350 | 31 | ||

| West Parade | Lincoln | 1050–1300 | 144 |

| 1275–1375 | 35 | ||

| Total | 2801 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Holmes, M.; Hamerow, H.; Thomas, R. Close Companions? A Zooarchaeological Study of the Human–Cattle Relationship in Medieval England. Animals 2021, 11, 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11041174

Holmes M, Hamerow H, Thomas R. Close Companions? A Zooarchaeological Study of the Human–Cattle Relationship in Medieval England. Animals. 2021; 11(4):1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11041174

Chicago/Turabian StyleHolmes, Matilda, Helena Hamerow, and Richard Thomas. 2021. "Close Companions? A Zooarchaeological Study of the Human–Cattle Relationship in Medieval England" Animals 11, no. 4: 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11041174

APA StyleHolmes, M., Hamerow, H., & Thomas, R. (2021). Close Companions? A Zooarchaeological Study of the Human–Cattle Relationship in Medieval England. Animals, 11(4), 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11041174