Insect Protein-Based Diet as Potential Risk of Allergy in Dogs

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Canine Sera

2.2. Mealworm Proteins Preparation and Characterization

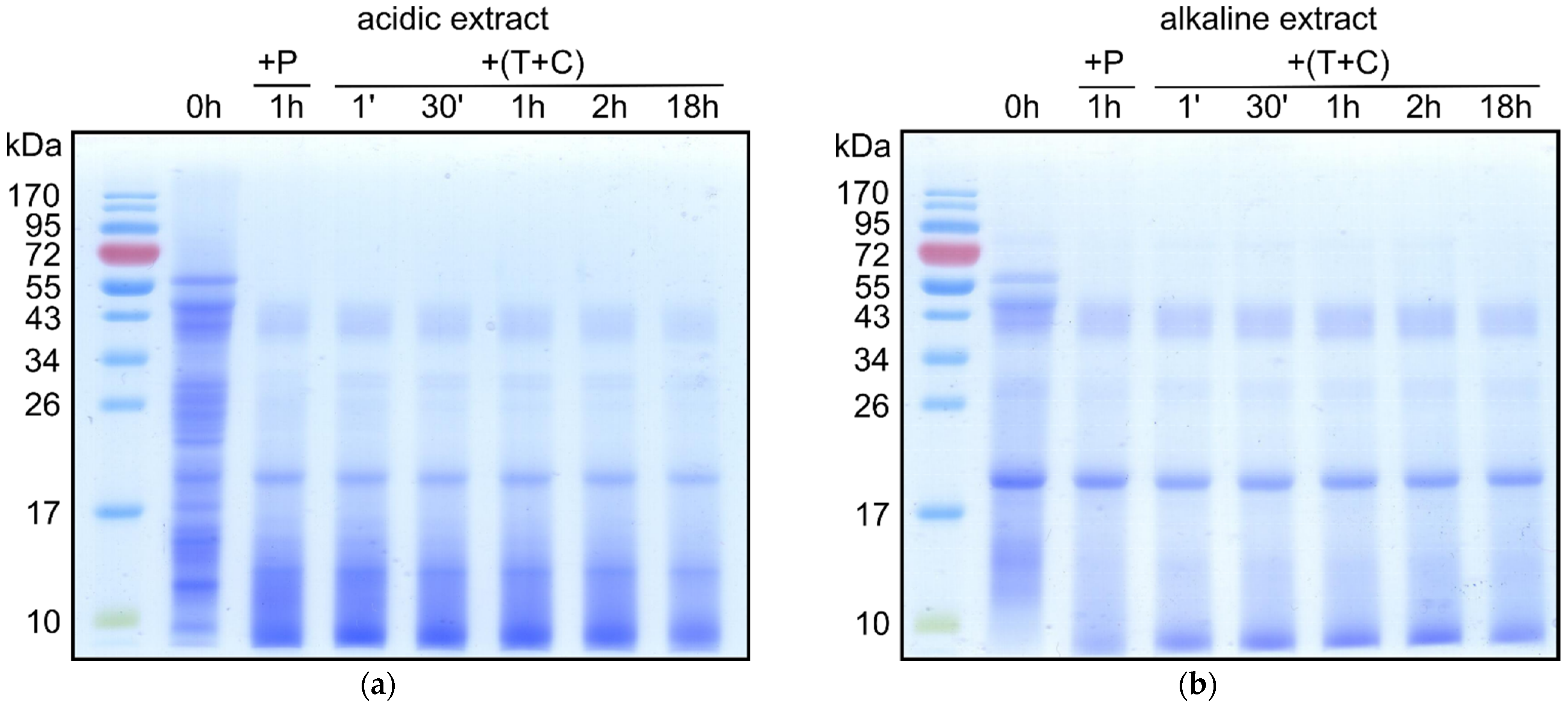

2.2.1. Digestibility of Mealworm Proteins

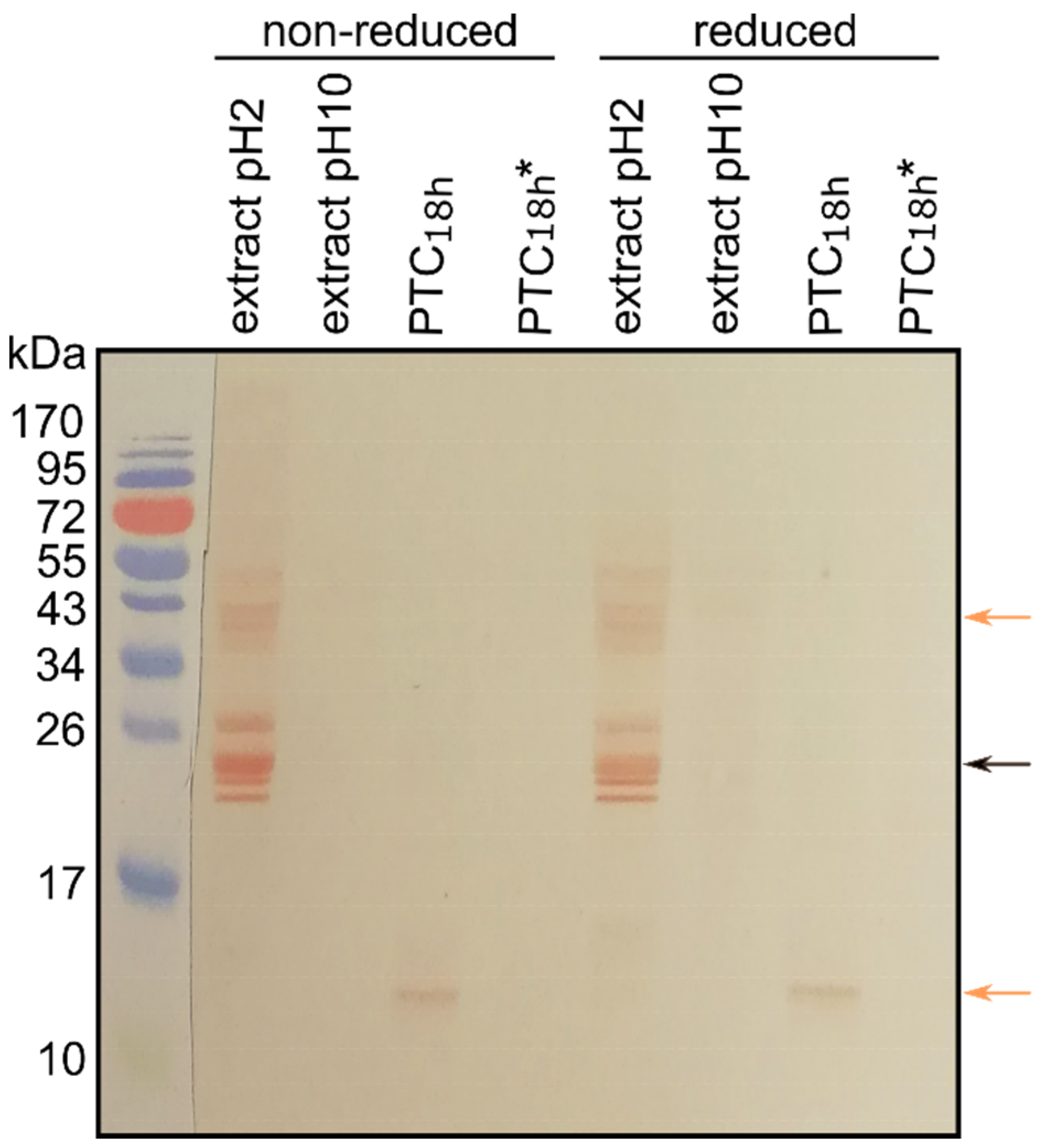

2.2.2. SDS-PAGE of Mealworm Proteins

2.3. Western Blot with Canine Sera

Statistical Analysis

2.4. Allergen Identification

2.4.1. Mass Spectrometry Analysis

2.4.2. Prediction of Allergenicity

3. Results

3.1. Mite-Specific IgE Antibodies in Canine Sera

3.2. Isolation of Mealworm Proteins

3.3. Digestibility of Mealworm Proteins

3.4. Cross-Reactivity of Mealworm Extract Proteins and Canine Sera IgEs

3.5. Identification of Potential Mealworm Protein Allergens

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pinotti, L.; Giromini, C.; Ottoboni, M.; Tretola, M.; Marchis, D. Review: Insects and former foodstuffs for upgrading food waste biomasses/streams to feed ingredients for farm animals. Animal 2019, 13, 1365–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berggren, Å.; Jansson, A.; Low, M. Approaching ecological sustainability in the emerging insects-as-food industry. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2019, 34, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Waterhouse, G.I.N.; You, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Ma, L.; Gao, J.; Dong, Y. Transforming insect biomass into consumer wellness foods: A review. Food Res. Int. 2016, 89 Pt 1, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purschke, B.; Mendez Sanchez, Y.D.; Jägera, H. Centrifugal fractionation of mealworm larvae (Tenebrio molitor, L.) for protein recovery and concentration. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 89, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.V.; Sanjinez-Argandoña, E.J.; Linzmeier, A.M.; Cardoso, C.A.; Macedo, M.L. Food value of mealworm grown on Acrocomia aculeata pulp flour. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broekman, H.C.H.P.; Knulst, A.C.; de Jong, G.; Gaspari, M.; den Hartog Jager, C.F.; Houben, G.F.; Verhoeckx, K.C.M. Is mealworm or shrimp allergy indicative for food allergy to insects? Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, S.G.O.; Bieber, T.; Dahl, R.; Friedmann, P.S.; Lanier, B.Q.; Lockey, R.F.; Motala, C.; Ortega Martell, J.A.; Platts-Mills, T.A.E.; Ring, J.; et al. Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use: Report of the nomenclature review committee of the world allergy organization. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004, 113, 832–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Gier, S.; Verhoeckx, K. Insect (food) allergy and allergens. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 100, 82–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Martinis, M.; Sirufo, M.M.; Suppa, M.; Ginaldi, L. New perspectives in food allergy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kang, M.H.; Park, H.M. Putative peanut allergy-induced urticaria in a dog. Can. Vet. J. 2012, 53, 1203–1206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rostaher, A.; Fischer, N.M.; Kümmerle-Fraune, C.; Couturier, N.; Jacquenet, S.; Favrot, C. Probable walnut-induced anaphylactic reaction in a dog. Vet. Dermatol. 2017, 28, 251.e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricoti, I.; Noli, C. An open label clinical trial to evaluate the utility of a hydrolysed fish and rice starch elimination diet for the diagnosis of adverse food reactions in dogs. Vet. Dermatol. 2018, 29, 408.e134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hensel, P.; Santoro, D.; Favrot, C.; Hill, P.; Griffin, C. Canine atopic dermatitis: Detailed guidelines for diagnosis and allergen identification. BMC Vet. Res. 2015, 11, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Popescu, F.D. Cross-reactivity between aeroallergens and food allergens. World J. Methodol. 2015, 5, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barre, A.; Pichereaux, C.; Velazquez, E.; Maudouit, A.; Simplicien, M.; Garnier, L.; Bienvenu, F.; Bienvenu, J.; Burlet-Schiltz, O.; Auriol, C.; et al. Insights into the allergenic potential of the edible Yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor). Foods 2019, 8, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fernández-Caldas, E.; Puerta, L.; Caraballo, L. Mites and allergy. Chem. Immunol. Allergy 2014, 100, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivry, T.; Mueller, R.S. Critically appraised topic on adverse food reactions of companion animals (8): Storage mites in commercial pet foods. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Strojan, K.; Leonardi, A.; Bregar, V.B.; Križaj, I.; Svete, J.; Pavlin, M. Dispersion of nanoparticles in different media importantly determines the composition of their protein corona. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leonardi, A.; Biass, D.; Kordiš, D.; Stöcklin, R.; Favreau, P.; Križaj, I. Conus consors snail venom proteomics proposes functions, pathways, and novel families involved in its venomic system. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 11, 5046–5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiers, M.W.E.J.; Kleter, G.A.; Nijland, H.; Peijnenburg, A.A.C.M.; Nap, J.P.; van Ham, R.C.H.J. Allermatch, a webtool for the prediction of potential allergenicity according to current FAO/WHO Codex alimentarius guidelines. BMC Bioinform. 2004, 5, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kröger, S.; Heide, C.; Zentek, J. Evaluation of an extruded diet for adult dogs containing larvae meal from the Black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens). Animl. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020, 270, 114699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilburn, L.R.; Carlson, A.T.; Lewis, E.; Rossoni Serao, M.C. Cricket (Gryllodes sigillatus) meal fed to healthy adult dogs does not affect general health and minimally impacts apparent total tract digestibility. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 98, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Böhm, T.M.S.A.; Klinger, C.J.; Gedon, N.; Udraite, L.; Hiltenkamp, K.; Mueller, R.S. Effekt eines insektenprotein-basierten futters auf die symptomatik von futtermittelallergischen hunden. Tierarztl. Prax. Ausg. K 2018, 46, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Broekhoven, S.; Bastiaan-Net, S.; de Jong, N.W.; Wichers, H.J. Influence of processing and in vitro digestion on the allergic cross-reactivity of three mealworm species. Food Chem. 2016, 196, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pali-Schöll, I.; Verhoeckx, K.; Mafra, I.; Bavaro, S.L.; Mills, E.N.C.; Monaci, L. Allergenic and novel food proteins: State of the art and challenges in the allergenicity assessment. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 84, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraballo, L.; Valenta, R.; Puerta, L.; Pomés, A.; Zakzuk, J.; Fernandez-Caldas, E.; Acevedo, N.; Sanchez-Borges, M.; Ansotegui, I.; Zhang, L.; et al. The allergenic activity and clinical impact of individual IgE-antibody binding molecules from indoor allergen sources. World Allergy Organ. J. 2020, 13, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhoeckx, K.; Broekman, H.; Knulst, A.; Houben, G. Allergenicity assessment strategy for novel food proteins and protein sources. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016, 79, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, R.S.; Janda, J.; Jensen-Jarolim, E.; Rhyner, C.; Marti, E. Allergens in veterinary medicine. Allergy 2016, 71, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotnik, T. Retrospective study of presumably allergic dogs examined over a one-year period at the Veterinary Faculty, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. Vet. Arhiv 2007, 77, 453–462. [Google Scholar]

- Leni, G.; Tedeschi, T.; Faccini, A.; Pratesi, F.; Folli, C.; Puxeddu, I.; Migliorini, P.; Gianotten, N.; Jacobs, J.; Depraetere, S.; et al. Shotgun proteomics, in-silico evaluation and immunoblotting assays for allergenicity assessment of lesser mealworm, black soldier fly and their protein hydrolysates. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Klueber, J.; Costa, J.; Randow, S.; Codreanu-Morel, F.; Verhoeckx, K.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Ollert, M.; Hoffmann-Sommergruber, K.; Morisset, M.; Holzhauser, T.; et al. Homologous tropomyosins from vertebrate and invertebrate: Recombinant calibrator proteins in functional biological assays for tropomyosin allergenicity assessment of novel animal foods. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2020, 50, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nebbia, S.; Lamberti, C.; Giorgis, V.; Giuffrida, M.G.; Manfredi, M.; Marengo, E.; Pessione, E.; Schiavone, A.; Boita, M.; Brussino, L.; et al. The cockroach allergen-like protein is involved in primary respiratory and food allergy to Yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor). Clin. Exp. Allergy 2019, 49, 1379–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, F.; Doyen, V.; Debaugnies, F.; Mazzucchelli, G.; Caparros, R.; Alabi, T.; Blecker, C.; Haubruge, E.; Corazza, F. Limited cross reactivity among arginine kinase allergens from mealworm and cricket edible insects. Food Chem. 2019, 276, 714–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verhoeckx, K.C.M.; van Broekhoven, S.; den Hartog-Jager, C.F.; Gaspari, M.; de Jong, G.A.H.; Wichers, H.J.; van Hoffen, E.; Houben, G.F.; Knulst, A.C. House dust mite (Der P 10) and crustacean allergic patients may react to food containing Yellow mealworm proteins. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 65, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, M.G.; Woodfolk, J.A.; Schuyler, A.J.; Stillman, L.C.; Chapman, M.D.; Platts-Mills, T.A. Half-life of IgE in serum and skin: Consequences for anti-IgE therapy in patients with allergic disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barre, A.; Pichereaux, C.; Simplicien, M.; Burlet-Schiltz, O.; Benoist, H.; Rougé, P. A proteomic- and bioinformatic-based identification of specific allergens from edible insects: Probes for future detection as food ingredients. Foods 2021, 10, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivry, T.; Bexley, J.; Mougeot, I. Extensive protein hydrolyzation is indispensable to prevent IgE-mediated poultry allergen recognition in dogs and cats. BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 13, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Mite | Positive Serum | Negative Serum | Borderline Serum |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. siro | |||

| CH (n = 10) | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| CA (n = 21) | 14 | 7 | 0 |

| T. putrescentiae | |||

| CH (n = 10) | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| CA (n = 21) | 14 | 7 | 0 |

| D. farinae | |||

| CH (n = 10) | 7 | 1 | 2 |

| CA (n = 21) | 17 | 4 | 0 |

| D. pteronyssinus | |||

| CH (n = 10) | 1 | 9 | 0 |

| CA (n = 21) | 1 | 20 | 0 |

| Cross-Reactivity with Mealworm Proteins | CH Dogs (n = 10) | CA Dogs (n = 21) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgE-Positive (n = 8) | IgE-Negative (n = 1) | ∑ | IgE-Positive (n = 14) | IgE-Negative (n = 7) | ∑ | |

| Before digestion (34–55 kDa) | 6 | 0 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 13 |

| After digestion (14 kDa) | 5 | 0 | 5 | 11 | 6 | 17 |

| Protein Extract | Identified PROTEIN | NCBI Accession | S. Mill Score | Distinct Peptides | Seq. Coverage | Matched Peptide Sequences | Theoretical Mass | pI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 2 | tropomyosin [Tenebrio molitor] | QBM01048 | 55.92 | 5 | 17 | LAEASQAADESFR LAEASQAADESFRMCK SQQDEERMDQLTNQLK SQQDEERMDQLTNQLKEAR TLTNAESEMAALNR | 32,428.5 | 4.8 |

| Tm-E1a cuticular protein [Tenebrio molitor] | AAB34025 | 54.65 | 3 | 20 | VASPAVSVHPAPAVR YAAPAVASVGYAAPALR YAAPAVASVGYAAPAVR | 23,188.5 | 9.54 | |

| odorant-binding protein 14 [Tenebrio molitor] | AJM71488 | 49.73 | 5 | 35 | KTGVATEAGDTNVEVLK ATPEETAYDTFK LKHVASDEEVDKIVQK TGVATEAGDTNVEVLK TGVATEAGDTNVEVLKAK | 14,706.1 | 7.58 | |

| Larval cuticle protein F1 [Tenebrio molitor] | Q9TXD9 | 43.71 | 4 | 50 | GLIGAPIAAPIAAPLATSVVSTR SLYGGYGSGLGIAR STPGGYGSGLIGGAYGSGLIGGGLYGAR YGLGAPALGHGLIGGAHLY | 14,566.8 | 9.63 | |

| 28 kDa desiccation stress protein [Tenebrio molitor] | AAB41285 | 41.31 | 3 | 26 | HKETIPSKTEICSTATSLR TKNVALGVFDALVAPCSHINEV VVDDCLPDSAKGLPSLGVK | 24,833.7 | 5.37 | |

| apolipophorin-III [Tenebrio molitor] | CDF77373 | 24.52 | 2 | 9 | NLDDGLKTAVAQVEK NLDDGLKTAVAQVEKLVK | 21,106.3 | 8.63 | |

| 56 kDa early-stage encapsulation-inducing protein [Tenebrio molitor] | BAA78480 | 21.59 | 1 | 2 | GVPQYTVGQYGIPR | 62,446 | 8.33 | |

| tropomyosin, partial [Zophobas atratus] | QCI56576 | 20.18 | 2 | 22 | EVDRLEDELVAEKER FLAEEADKKYDEVAR | 15,572.4 | 4.58 | |

| cockroach allergen-like protein [Tenebrio molitor] | Q7YZB8 | 11.74 | 1 | 2 | ALDEVQTLAQR | 65,481.44 | 4.08 | |

| nero, partial [Cryphaeus sp. INB181] | AUW69182 | 6.32 | 1 | 9 | NIQSKEAIEALGAGLK | 18,852.6 | 4.7 | |

| glucose dehydrogenase, partial [Cryphaeus sp. INB181] | AUW87486 | 3.17 | 1 | 2 | IRRGSR | 33,739.6 | 10.23 | |

| pH 10 | odorant-binding protein 14 [Tenebrio molitor] | AJM71488 | 136.86 | 8 | 60 | ATPEETAYDTFK KTGVATEAGDTNVEVLK KTGVATEAGDTNVEVLKAK LKHVASDEEVDKIVQK TGVATEAGDTNVEVLK TGVATEAGDTNVEVLKAK CIYDSKPDFSPID ISKECQQVSGVSQETIDKVR | 14,706.1 | 7.58 |

| hexamerin 2 [Tenebrio molitor] | AAK77560 | 90.69 | 5 | 10 | GGMTYQFYVMVSK HLLGYSQQPLTYFK HYYNEHDLMYQGVEVK NVAAYSKPEVVEQFYK YDNRGEAFYYMYQQILAR | 84,543.1 | 6.18 | |

| apolipophorin-III [Tenebrio molitor] | CDF77373 | 68.15 | 5 | 22 | LSQTAAQLQQAAGPEATAK LSQTAAQLQQAAGPEATAKAK NLDDGLKTAVAQVEK NLDDGLKTAVAQVEKLVK QVQEKLSQTAAQLQQAAGPEATAK | 21,106.3 | 8.63 | |

| 56 kDa early-stage encapsulation-inducing protein [Tenebrio molitor] | BAA78480 | 59.91 | 4 | 11 | EYQGVVDEAQYEK GVPQYTVGQYGIPR GVQTIGQLR GVQTIGQLRQYYPTSLNVNPLLGR | 62,446 | 8.33 | |

| tropomyosin [Tenebrio molitor] | QBM01048 | 55.8 | 6 | 24 | KLAFVEDELEVAEDRVK LAEASQAADESFR MQAMK SQQDEERMDQLTNQLK SQQDEERMDQLTNQLKEAR TLTNAESEMAALNR | 32,428.5 | 4.8 | |

| alpha-amylase [Tenebrio molitor] | P56634 | 40.72 | 3 | 9 | GVLIDYMNHMIDLGVAGFR HMSPGDLSVIFSGLK NSIVHLFEWK | 51,240.7 | 4.53 | |

| aldehyde oxidase AOX1 [Tenebrio molitor] | AKZ17716 | 27.91 | 1 | 4 | IYTIEGIGDPLTGYHPVQEVLAK | 138,948.4 | 5.06 | |

| Tm-E1a cuticular protein [Tenebrio molitor] | AAB34025 | 23.51 | 2 | 13 | VASPAVSVHPAPAVR YAAPAVASVGYAAPAVR | 23,188.5 | 9.54 | |

| tropomyosin, partial [Zophobas atratus] | QCI56576 | 22 | 2 | 22 | EVDRLEDELVAEKER FLAEEADKKYDEVAR | 15,572.4 | 4.58 | |

| cytochrome P450 momooxigenase CYP4G123 | AKZ17712 | 19.81 | 1 | 3 | GIRGSTAEVPVELQTK | 58,314.8 | 8.99 | |

| 86 kDa early-stage encapsulation-inducing protein [Tenebrio molitor] | BAA81665 | 19.21 | 2 | 4 | HLLGYAYQPYTYHK VYVDANTETDAVVK | 90,623.9 | 6.62 | |

| nero, partial [Cryphaeus sp. INB181] | AUW69182 | 11.67 | 1 | 9 | NIQSKEAIEALGAGLK | 18,852.6 | 4.7 | |

| 28 kDa desiccation stress protein [Tenebrio molitor] | AAB41285 | 11.13 | 1 | 8 | VVDDCLPDSAKGLPSLGVK | 24,833.7 | 5.37 | |

| serpin1 [Tenebrio molitor] | BAI59109 | 39.76 | 3 | 12 | AEFLELPFKGNEASMMIVLPK AVLINALYFK TALHLPDDKETVESAIK | 44,213.9 | 6.17 | |

| glucose dehydrogenase, partial [Cryphaeus sp. INB181] | AUW87486 | 3.17 | 1 | 2 | IRRGSR | 33,739.6 | 10.23 |

| Sequence Identity in Allermatch | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80 AA Sliding Window Analysis | Full Sequence Alignement | |||||

| Protein | Allergen | # Hits > 35% Identity | % hits > 35% Identity | % | Overlap (AA) | E |

| tropomyosin (QCI56576) | Chi k 10 [Chironomus kiiensis] | 55 | 100 | 96.3 | 134 | 1.3−31 |

| Aed a 10 [Aedes aegypti] | 55 | 100 | 95.5 | 134 | 2.1−31 | |

| Lep s 1.0102 [Lepisma saccharina] | 55 | 100 | 96.7 | 90 | 1.1−19 | |

| tropomyosin (QBM01048) | Lep s 1.0101 [Lepisma saccharina] | 205 | 100 | 82.4 | 284 | 1.5−94 |

| Aed a 10 [Aedes aegypti] | 205 | 100 | 77.1 | 284 | 1.1−87 | |

| Eup p 1 [Euphausia pacifica] | 205 | 100 | 68.3 | 284 | 2.0−76 | |

| alpha-amylase (P56634) | Bla g 11 [Blatella germanica] | 392 | 100 | 64.6 | 480 | 5.0−143 |

| Per a 11 [Periplaneta americana] | 392 | 100 | 58.9 | 477 | 2.1−125 | |

| Der f 4.0101 [Dermatophagoides farinae] | 392 | 100 | 49.5 | 497 | 4.1−69 | |

| hexamerin 2 (AAK77560) | Per a 3 [Periplaneta americana] | 397 | 63.72 | 39.1 | 665 | 7.7−46 |

| Bla g 3 [Blatella germanica] | 403 | 64.69 | 38.0 | 681 | 3.1−46 | |

| 86 kDa early-stage encapsulation-inducing protein (BAA81665) | Per a 3 [Periplaneta americana] | 431 | 63.85 | 37.9 | 702 | 1.8−44 |

| Bla g 3 [Blatella germanica] | 392 | 58.07 | 37.1 | 672 | 1.6−41 | |

| cockroach allergen-like protein (Q7YZB8) | Bla g 1 [Blatella germanica] | 340 | 65.89 | 35.9 | 412 | 1.5−42 |

| Per a 1 [Periplaneta americana] | 259 | 50.15 | 35.6 | 413 | 4.0−40 | |

| glucose dehydrogenase (AUW87486) | Mala s 12 [Malassezia sympodialis] | 69 | 31.22 | 32.4 | 278 | 6.7−21 |

| serpin1 (BAI59109) | Tri a 33 [Triticum aestivum] | 89 | 28.25 | 32.0 | 369 | 1.0−28 |

| Gal d 2.0101 [Gallus gallus] | 14 | 4.4 | 28.1 | 388 | 1.7−27 | |

| Tm-E1a cuticular protein (AAB34025) | Poa p 5 [Poa pratensis] | 40 | 24.39 | 29.6 | 226 | 0.11 |

| Lol p 5 [Lolium perenne] | 78 | 47.56 | 28.3 | 198 | 9.0−07 | |

| Poa p 5 [Poa pratensis] | 61 | 37.20 | 27.2 | 246 | 0.97 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Premrov Bajuk, B.; Zrimšek, P.; Kotnik, T.; Leonardi, A.; Križaj, I.; Jakovac Strajn, B. Insect Protein-Based Diet as Potential Risk of Allergy in Dogs. Animals 2021, 11, 1942. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11071942

Premrov Bajuk B, Zrimšek P, Kotnik T, Leonardi A, Križaj I, Jakovac Strajn B. Insect Protein-Based Diet as Potential Risk of Allergy in Dogs. Animals. 2021; 11(7):1942. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11071942

Chicago/Turabian StylePremrov Bajuk, Blanka, Petra Zrimšek, Tina Kotnik, Adrijana Leonardi, Igor Križaj, and Breda Jakovac Strajn. 2021. "Insect Protein-Based Diet as Potential Risk of Allergy in Dogs" Animals 11, no. 7: 1942. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11071942

APA StylePremrov Bajuk, B., Zrimšek, P., Kotnik, T., Leonardi, A., Križaj, I., & Jakovac Strajn, B. (2021). Insect Protein-Based Diet as Potential Risk of Allergy in Dogs. Animals, 11(7), 1942. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11071942