A Survey of Horse Selection, Longevity, and Retirement in Equine-Assisted Services in the United States

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Part I

3.1.1. Response Rate

3.1.2. Staff and Center Demographics

3.1.3. Horse Selection, Retirement, and Management

3.1.4. Horse and Personnel Training

3.2. Part II

3.2.1. Response Rate

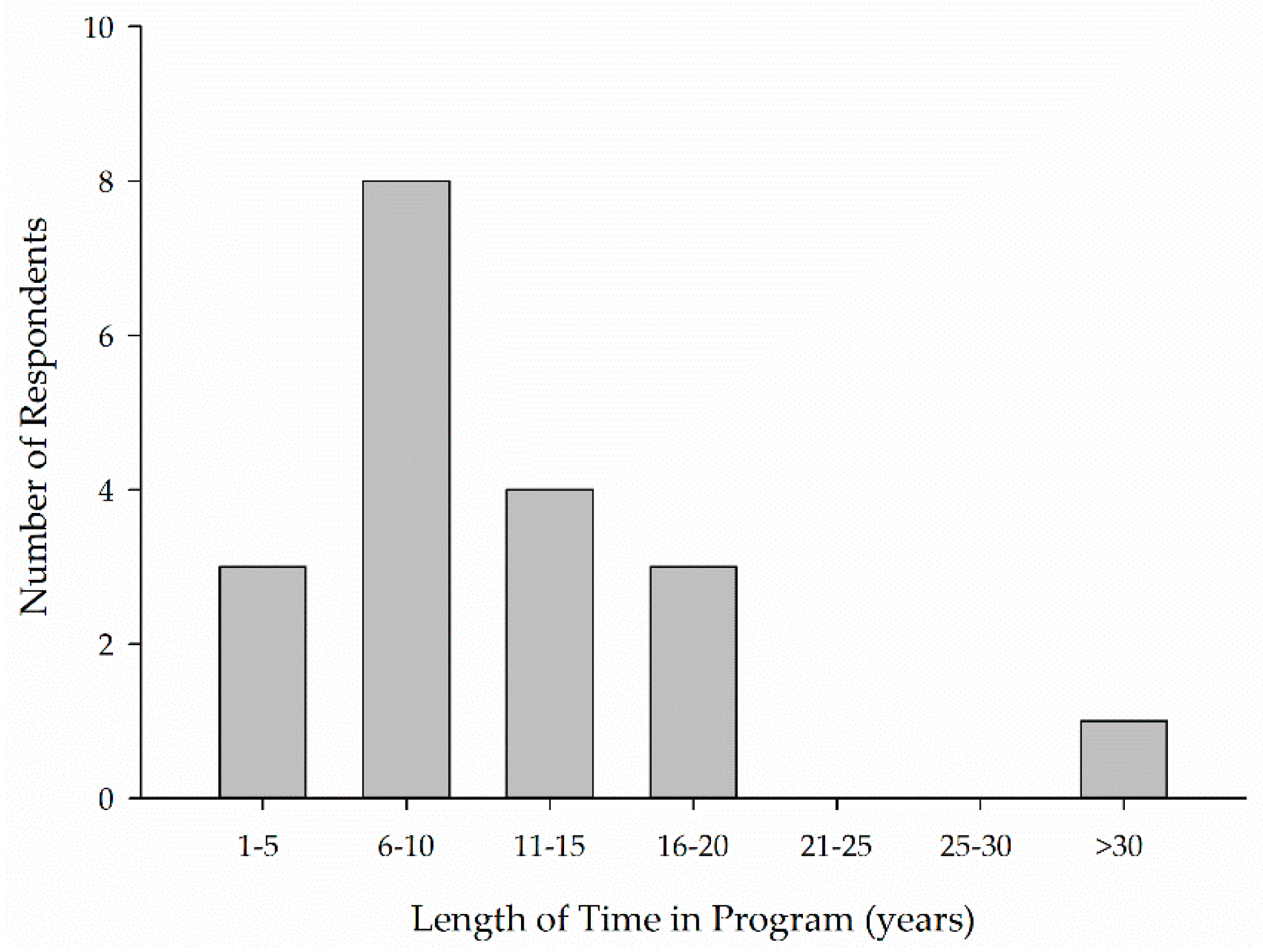

3.2.2. Staff and Center Demographics

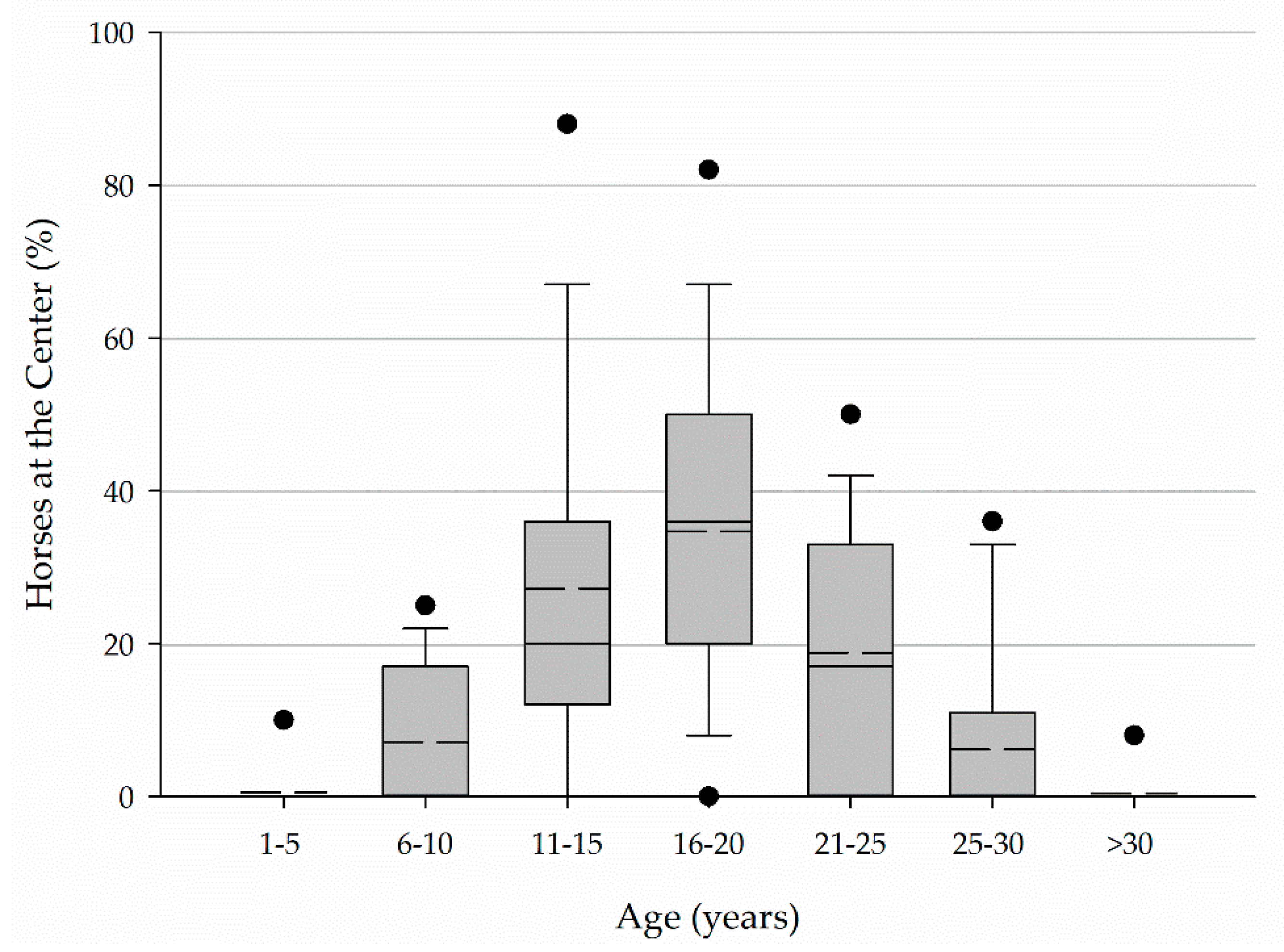

3.2.3. Horse Selection, Retirement, and Management

3.2.4. Relationships among Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Question | Response Format |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Multiple Selection; Open-ended (Other) |

| Multiple Selection; Open-ended (CHA Certified & Other) |

| Single Selection |

| Single Selection |

| Fill-in-the-blank |

| Fill-in-the-blank |

| Single Selection |

| Fill-in-the-blank; Open-ended (Other) |

| Fill-in-the-blank |

| Single Selection |

| Single Selection |

| Horse Selection and Management | |

| Multiple Selection; Open-ended (Other) |

| Likert-type scale (1 = very prepared, 5 = very unprepared) |

| Single Selection |

| Single Selection |

| Multiple Selection |

| Open-ended |

| Single Selection; Open-ended (Other) |

| Single Selection; Open-ended (Other) |

| Single Selection |

| Single Selection |

| Multiple Selection; Open-ended (Other) |

| Single Selection; Open-ended (Other) |

| Open-ended |

| Open-ended |

| Single Selection; Open-ended (Other) |

| Single Selection |

| Single Selection |

| Single Selection |

| Single Selection |

| Single Selection |

| Single Selection |

| Multiple Selection; Open-ended (Other) |

| Multiple Selection; Open-ended (Other) |

| Fill-in-the-blank |

| Single Selection |

| Fill-in-the-blank |

| Multiple Selection; Open-ended (Other) |

| Multiple Selection; Open-ended (Other) |

| Multiple Selection; Open-ended (Other) |

| Multiple Selection; Open-ended (Other) |

| Horse and Personnel Training | |

| Likert-type scale (1 = very prepared, 5 = very unprepared) |

| Single Selection; Open-ended (Other) |

| Single Selection |

| Multiple Selection; Open-ended (Other) |

| Single Selection |

| Open-ended |

| Single Selection |

| Single Selection |

| Multiple Selection; Open-ended (Other) |

| Single Selection |

| Single Selection |

| Single Selection |

| Single Selection |

| Single Selection |

| Single Selection |

| Single Selection |

| Multiple Selection; Open-ended (Other) |

| Question | Response Format |

|---|---|

| Multiple Selection; Open-ended (Other) |

| Fill-in-the-blank |

| Fill-in-the-blank |

| Sliding Scale (0–100%); Open-ended (Other) |

| Multiple Selection; Open-ended (Other) |

| Sliding Scale (0–100%) |

| Single Selection |

| Single Selection |

| Ranking; Open-ended (Other) |

References

- Wood, W.; Alm, K.; Benjamin, J.; Thomas, L.; Anderson, D.; Pohl, L.; Kane, M. Optimal Terminology for Services in the United States That Incorporate Horses to Benefit People: A Consensus Document. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2020, 27, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Horse Council Foundation. 2017 Economic Impact Study of the U.S. Horse Industry; American Horse Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Renker, L. The Process of Teaching Therapeutic Horseback Riding. In Proceedings of the North American Riding for the Handicapped Association 1993 Conference Proceedings, Lexington, KY, USA, 14 November 1993. [Google Scholar]

- NARHA. North American Riding for the Handicapped Association 2005 Fact Sheet; NARHA: Denver, CO, USA, 2006.

- PATH Intl. Professional Association of Therapeutic Horsemanship International 2017 Fact Sheet; PATH Intl.: Denver, CO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, R.; Wallach, K. Equine stress-related behaviors in therapeutic riding classes. In Proceedings of the 11th International Society for Equitation Science Conference, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 5–8 August 2015; p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Keeling, L.; Blomberg, A.; Ladewig, J. Horse-riding accidents: When the human-animal relationship goes wrong. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Society of Applied Ethology, Lillehammer, Norway, 17–21 August 1999; p. 86. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K.E.; Annest, J.L.; Gilchrist, J.; Bixby-Hammett, D.M. Non-fatal horse related injuries treated in emergency departments in the United States, 2001-2003. Br. J. Sports Med. 2006, 40, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, A.N.; Christensen, J.W. The application of learning theory in horse training. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 190, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, G.D.; Galindo-Gonzalez, S. Using Focus Group Interviews for Planning or Evaluating Extension Programs; University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, J.A.; More, S.J.; Hanlon, A.; Wall, P.G.; McKenzie, K.; Duggan, V. Use of qualitative methods to identify solutions to selected equine welfare problems in Ireland. Vet. Rec. 2012, 170, 442–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- PATH Intl. Professional Association of Therapeutic Horsemanship International Standards for Certification & Accreditation; PATH Intl.: Denver, CO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, A.; McGreevy, P.; Christensen, J. Principles of Learning Theory in Equitation. Available online: https://equitationscience.com/learning-theory/ (accessed on 7 September 2018).

- Marín Navas, C.; Delgado Bermejo, J.V.; McLean, A.K.; León Jurado, J.M.; Torres , A.; Navas González, F.J. Discriminant canonical analysis of the contribution of Spanish and Arabian purebred horses to the genetic diversity and population structure of Hispano-Arabian horses. Animals 2021, 11, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PATH Intl. PATH International 2015 Center Employment Analysis Executive Summary; PATH Intl.: Denver, CO, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, E.; Davis, A.; Splan, R.; Porr, C.A.S. Characterization of Horse Use in Therapeutic Horseback Riding Programs in the United States: A Pilot Survey. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2020, 92, 103157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PATH Intl. PATH Intl STRIDES; PATH Intl.: Denver, CO, USA, 2018; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H. Horse Use and Management in University Equine Programs. Master of Science Thesis, Murray State University, Murray, KY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.K.; Friend, T.H.; Evans, J.W.; Bushong, D.M. Behavioral assessment of horses in therapeutic riding programs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1999, 63, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, S.; Berger, J.M.; Ellis, A.D.; Mullard, J. Behavioral observations and comparisons of nonlame horses and lame horses before and after resolution of lameness by diagnostic analgesia. J. Vet. Behav. 2018, 26, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, S.; Berger, J.M.; Ellis, A.D.; Mullard, J. Can the presence of musculoskeletal pain be determined from the facial expressions of ridden horses (FEReq)? J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2017, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council of the National Academies. Nutrient Requirements of Horses, 6th ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Scholey, A.B.; Harper, S.; Kennedy, D.O. Cognitive demand and blood glucose. Physiol. Behav. 2001, 73, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankins, E. The Influence of a Rider with a Disability on the Equine Walk. Undergraduate Thesis, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bornmann, T. Riders’ perceptions, understanding and theoretical application of learning theory. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2016, 15, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telatin, A.; Baragli, P.; Green, B.; Gardner, O.; Bienas, A. Testing theoretical and empirical knowledge of learning theory by surveying equestrian riders. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2016, 15, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Member Center | Premier Accredited Center | |

|---|---|---|

| 1–5 years | 6 | 0 |

| 6–10 years | 2 | 2 |

| 11–15 years | 2 | 0 |

| 16–20 years | 0 | 0 |

| 21–25 years | 3 | 0 |

| 26–30 years | 0 | 1 |

| 31–35 years | 0 | 2 |

| 36–40 years | 0 | 1 |

| Training Technique | Description |

|---|---|

| Negative Reinforcement | Removal of an aversive stimulus in response to a desired behavior |

| Positive Reinforcement | Addition of a rewarding stimulus in response to a desired behavior |

| Negative Punishment | Removal of a rewarding stimulus in response to an undesired behavior |

| Positive Punishment | Addition of an aversive stimulus in response to an undesired behavior |

| Systematic Desensitization | Exposure to increasing levels of an arousing stimulus until habituation or a decrease in responsiveness to the stimulus occurs |

| Number of Members Invited to Participate | Number of Complete Responses | Response Rate (%) | Number of Incomplete Responses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Hippotherapy Association (AHA) | 2500 | 70 | 2.8 | 75 |

| Professional Association of Therapeutic Horsemanship, International (PATH Intl.) | 9000 | 41 | 0.5 | 52 |

| eagala | 2000 | 11 | 0.6 | 24 |

| Certified Horsemanship Association (CHA) | 12,500 | 54 | 0.4 | 38 |

| Total | 26,000 | 176 | 0.7 | 189 |

| Initial Screening | Pre-Purchase or Donation Exam | Acclimation Period | Trial Period | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency [n (%)] | 168 (96%) | 105 (60%) | 147 (84%) | 159 (90%) | 20 (11%) |

| AHA | PATH Intl. | eagala | CHA | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive or therapeutic riding [count (%)] | 50 (71%) | 40 (98%) | 5 (46%) | 44 (82%) | 139 (79%) |

| Equine assisted physical therapy/hippotherapy [count (%)] | 45 (64%) | 11 (27%) | 3 (27%) | 11 (20%) | 70 (40%) |

| Equine assisted occupational therapy/hippotherapy [count (%)] | 48 (69%) | 10 (24%) | 3 (27%) | 8 (15%) | 69 (39%) |

| Equine assisted speech therapy/hippotherapy [count (%)] | 26 (37%) | 4 (10%) | 3 (27%) | 4 (7%) | 37 (21%) |

| Equine assisted psychotherapy (EAP) or equine facilitated psychotherapy (EFP) [count (%)] | 22 (31%) | 12 (29%) | 8 (73%) | 17 (32%) | 59 (34%) |

| Equine assisted learning (EAL) [count (%)] | 27 (39%) | 21 (51%) | 8 (73%) | 35 (65%) | 91 (52%) |

| Adaptive driving [count (%)] | 8 (11%) | 8 (20%) | 2 (18%) | 7 (13%) | 25 (14%) |

| Interactive vaulting [count (%)] | 1 (1%) | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (11%) | 9 (5%) |

| Traditional riding lessons [count (%)] | 3 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 5 (3%) |

| Adaptive unmounted activities [count (%)] | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9%) | 4 (7%) | 5 (3%) |

| Other [count (%)] | 4 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) | 7 (4%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rankins, E.M.; Wickens, C.L.; McKeever, K.H.; Malinowski, K. A Survey of Horse Selection, Longevity, and Retirement in Equine-Assisted Services in the United States. Animals 2021, 11, 2333. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082333

Rankins EM, Wickens CL, McKeever KH, Malinowski K. A Survey of Horse Selection, Longevity, and Retirement in Equine-Assisted Services in the United States. Animals. 2021; 11(8):2333. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082333

Chicago/Turabian StyleRankins, Ellen M., Carissa L. Wickens, Kenneth H. McKeever, and Karyn Malinowski. 2021. "A Survey of Horse Selection, Longevity, and Retirement in Equine-Assisted Services in the United States" Animals 11, no. 8: 2333. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082333