How Do Hunters Hunt Wild Boar? Survey on Wild Boar Hunting Methods in the Federal State of Lower Saxony

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Evaluating the opinion and attitudes of stakeholders, hunters, and the general public;

- Incorporating scientific background, social needs, and social attitude;

- Monitoring the success of management measures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area: Lower Saxony

2.2. Data Collection

3. Results

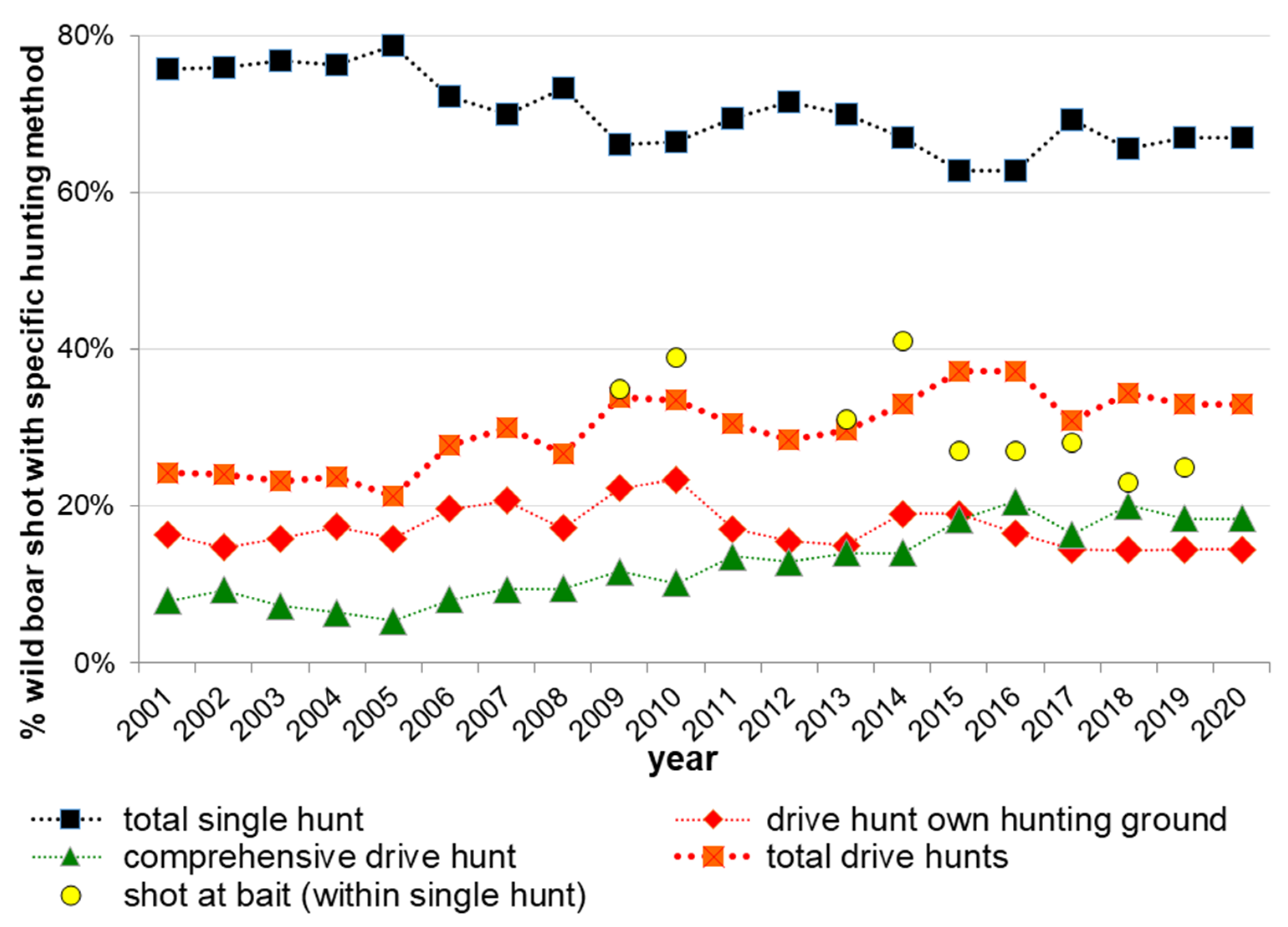

3.1. Hunting Methods + Hunting Bags

How Many Wild Boar Were Shot in Your Own Hunting Ground during the Last Season with Which Hunting Method?

3.2. How to Hunt?

3.2.1. Do You Bait Wild Boar in Your Hunting Ground?

3.2.2. Do You Conduct Drive Hunts on Wild Boar?

3.2.3. On the Drive Hunts You Conduct: Wild Boar Is (A) Main Species or (B) Incidental Species (“Bycatch”)? Which Other Game Species Are Hunted?

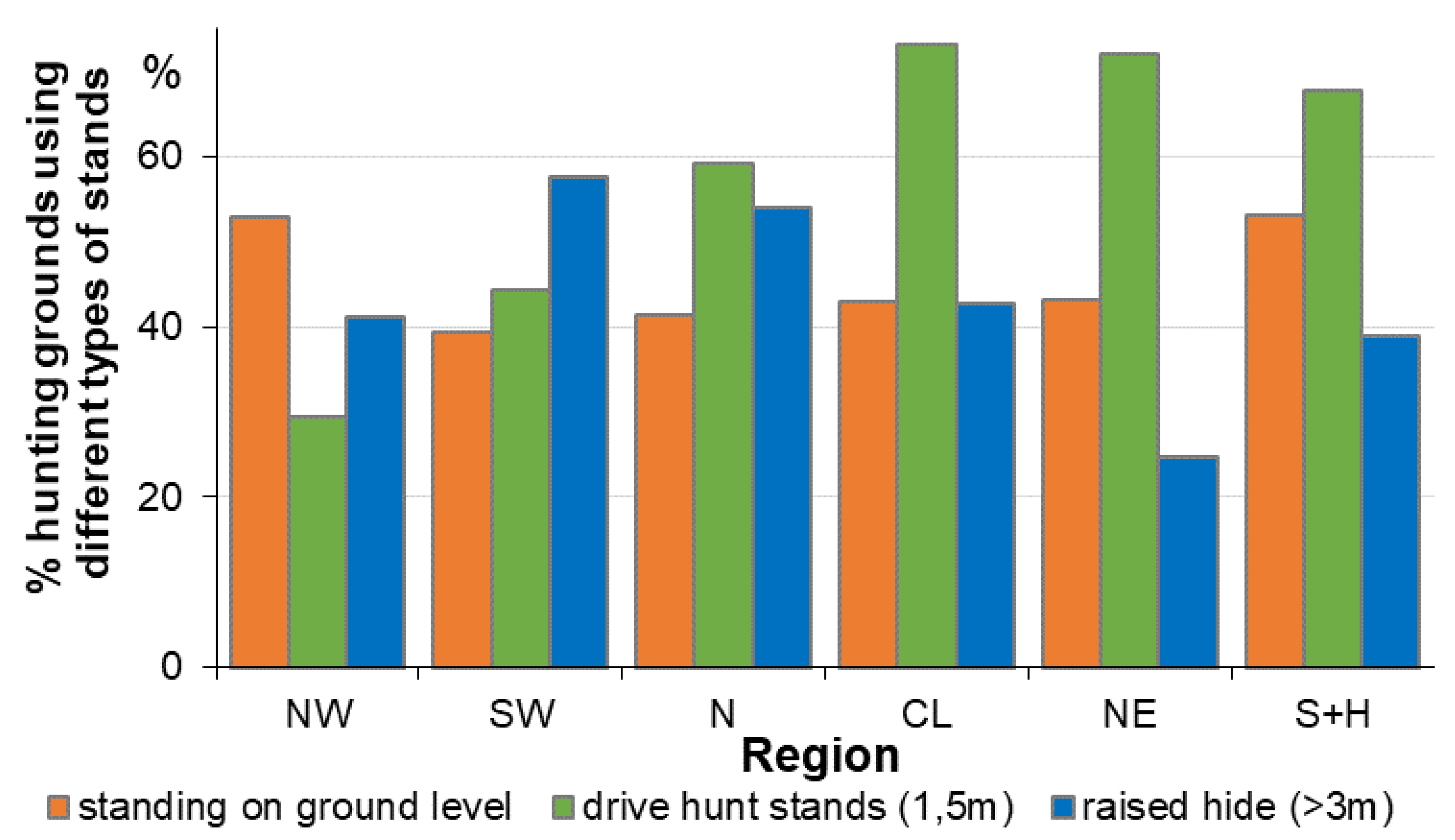

3.2.4. How Do You Conduct Drive Hunts?

- (a)

- conduction “hunting method”

- (b)

- hunting party

- (c)

- type of stands*

3.2.5. Do You Have Any Difficulties in Conducting Drive Hunts? Which Are These?

4. Discussion

4.1. Hunting Methods and Hunting Bags

4.2. How to Hunt? (With a Discussion on Efficiency Based on Literature Comparison)

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keuling, O.; Baubet, E.; Duscher, A.; Ebert, C.; Fischer, C.; Monaco, A.; Podgórski, T.; Prevot, C.; Ronnenberg, K.; Sodeikat, G.; et al. Mortality rates of wild boar Sus scrofa L. in central Europe. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2013, 59, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massei, G.; Kindberg, J.; Licoppe, A.; Gačić, D.; Šprem, N.; Kamler, J.; Baubet, E.; Hohmann, U.; Monaco, A.; Ozoliņš, J.; et al. Wild boar populations up, numbers of hunters down? A review of trends and implications for Europe. Pest Manag. Sci. 2015, 71, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gortázar, C.; Ferroglio, E.; Höfle, U.; Frölich, K.; Vicente, J. Diseases shared between wildlife and livestock: A European perspective. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2007, 53, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schley, L.; Dufrêne, M.; Krier, A.; Frantz, A.C. Patterns of crop damage by wild boar (Sus scrofa) in Luxembourg over a 10-year period. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2008, 54, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedbloed, D.J.; Van Hooft, P.; Megens, H.-J.; Bosch, T.; Lutz, W.; Van Wieren, S.E.; Ydenberg, R.C.; Prins, H.H.T. Host genetic heterozygosity and age are important determinants of porcine circovirus type 2 disease prevalence in European wild boar. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2014, 60, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, R.; Jacobson, S.; Ueda, G. Public Perceptions of Significant Wildlife in Hyogo, Japan. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2014, 19, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frackowiak, W.; Gorczyca, S.; Merta, D.; Wojciuch-Ploskonka, M. Factors affecting the level of damage by wild boar in farmland in north-eastern Poland. Pest Manag. Sci. 2013, 69, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagos, L.; Picos, J.; Valero, E. Temporal pattern of wild ungulate-related traffic accidents in northwest Spain. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2012, 58, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frauendorf, M.; Gethöffer, F.; Siebert, U.; Keuling, O. The influence of environmental and physiological factors on the litter size of wild boar (Sus scrofa) in an agriculture dominated area in Germany. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 541, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briedermann, L.; Dittrich, G.; Goretzki, J.; Stubbe, C.; Horstmann, H.-D.; Schreiber, R.; Klier, E.; Siefke, A.; Mehlitz, S. Ent-wicklung der Schalenwildbestände in der DDR und Möglichkeiten der Bestandsregulierung. Beitr. Jagd-und Wildforschung 1986, 14, 16–32. [Google Scholar]

- Massei, G.; Cowan, D. Fertility control to mitigate human–wildlife conflicts: A review. Wildl. Res. 2014, 41, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Massei, G.; Roy, S.; Bunting, R. Too many hogs? A review of methods to mitigate impact by wild boar and feral hogs. Hum. Wildl. Interact. 2011, 5, 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Vetter, S.G.; Ruf, T.; Bieber, C.; Arnold, W. What Is a Mild Winter? Regional Differences in Within-Species Responses to Climate Change. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolon, V.; Dray, S.; Loison, A.; Zeileis, A.; Fischer, C.; Baubet, E. Responding to spatial and temporal variations in predation risk: Space use of a game species in a changing landscape of fear. Can. J. Zool. 2009, 87, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keuling, O.; Nahlik, A.; Fonseca, C. Wild boar research—A never ending story? Wildl. Biol. Pract. 2014, 10, i–ii. [Google Scholar]

- Ballari, S.A.; Barrios-García, M.N. A review of wild boar Sus scrofa diet and factors affecting food selection in native and introduced ranges. Mammal Rev. 2014, 44, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briedermann, L. Schwarzwild, 3rd ed.; Franckh-Kosmos GmbH & Co., KG: Stuttgart, Germany, 2009; p. 596. [Google Scholar]

- Morelle, K.; Podgórski, T.; Prévot, C.; Keuling, O.; Lehaire, F.; Lejeune, P. Towards understanding wild boar Sus scrofa movement: A synthetic movement ecology approach. Mammal Rev. 2015, 45, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, A.; Acevedo, P.; Rodríguez, O.; Naves, J.; Obeso, J.R. Biotic and abiotic factors modulating wild boar relative abundance in Atlantic Spain. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2014, 60, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prévot, C.; Licoppe, A. Comparing red deer (Cervus elaphus L.) and wild boar (Sus scrofa L.) dispersal patterns in southern Belgium. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2013, 59, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keuling, O.; Lauterbach, K.; Stier, N.; Roth, M. Hunter feedback of individually marked wild boar Sus scrofa L.: Dispersal and efficiency of hunting in northeastern Germany. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2010, 56, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgórski, T.; Lusseau, D.; Scandura, M.; Sönnichsen, L.; Jędrzejewska, B. Long-Lasting, Kin-Directed Female Interactions in a Spatially Structured Wild Boar Social Network. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glikman, J.A.; Frank, B. Human Dimensions of Wildlife in Europe: The Italian Way. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2011, 16, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treves, A.; Wallace, R.B.; Naughton-Treves, L.; Morales, A. Co-Managing Human–Wildlife Conflicts: A Review. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2006, 11, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keuling, O. Human dimension in wild boar management. In Proceedings of the 31st IUGB Congress, Brussels, Belgium, 27–29 August 2013; p. 74. [Google Scholar]

- von Essen, E. How Wild Boar Hunting Is Becoming a Battleground. Leis. Sci. 2019, 42, 552–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keuling, O.; Strauß, E.; Siebert, U. Regulating wild boar populations is somebody else’s problem! Human dimension in wild boar management. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 554–555, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M.; Momose, H.; Mihira, T. Both environmental factors and countermeasures affect wild boar damage to rice paddies in Boso Peninsula, Japan. Crop. Prot. 2011, 30, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, G.; Kanzaki, N.; Koganezawa, M. Changes in the Structure of the Japanese Hunter Population from 1965 to 2005. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2010, 15, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, B.; Mónaco, A.; Bath, A.J. Beyond standard wildlife management: A pathway to encompass human dimension findings in wild boar management. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2015, 61, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabrina, S.; Jean-Michel, G.; Carole, T.; Serge, B.; Eric, B. Pulsed resources and climate-induced variation in the reproductive traits of wild boar under high hunting pressure. J. Anim. Ecol. 2009, 78, 1278–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servanty, S.; Gaillard, J.-M.; Ronchi, F.; Focardi, S.; Baubet, E.; Gimenez, O. Influence of harvesting pressure on demographic tactics: Implications for wildlife management. J. Appl. Ecol. 2011, 48, 835–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gethöffer, F.; Sodeikat, G.; Pohlmeyer, K. Reproductive parameters of wild boar (Sus scrofa) in three different parts of Germany. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2007, 53, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellina, S. Effects of Supplemental Feeding on the Body Condition and Reproductive State of Wild Boar Sus scrofa in Luxembourg. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sussex, Sussex, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bieber, C.; Ruf, T. Population dynamics in wild boar Sus scrofa: Ecology, elasticity of growth rate and implications for the management of pulsed resource consumers. J. Appl. Ecol. 2005, 42, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servanty, S. Dynamique d´une Population Chassée de Sanglier (Sus scrofa scrofa) en Milieu Forestier. Ph.D. Thesis, Univerité Claude Bernard, Lyon, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Servanty, S.; Gaillard, J.-M.; Togo, C.; Lebreton, J.-D.; Baubet, E.; Klein, F. Population management based on incomplete data: Modelling the case of wild boar (Sus scrofa scrofa) in France. In Proceedings of the XXVII Congress of IUGB, Hanover, Germany, 28 August–3 September 2005; pp. 256–257. [Google Scholar]

- Sodeikat, G.; Papendiek, J.; Richter, O.; Söndgerath, D.; Pohlmeyer, K. Modelling population dynamics of wild boar (Sus scrofa) in Lower Saxony, Germany. In Proceedings of the XXVII Congress of IUGB, Hanover, Germany, 28 August–3 September 2005; pp. 488–489. [Google Scholar]

- Caley, P.; Ottley, B. The Effectiveness of Hunting Dogs for Removing Feral Pigs (Sus Scrofa). Wildl. Res. 1995, 22, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dexter, N. The Effect of an Intensive Shooting Exercise from a Helicopter on the Behaviour of Surviving Feral Pigs. Wildl. Res. 1996, 23, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeman, R.; Hershberger, T.; Orzell, S.; Felix, R.; Killian, G.; Woolard, J.; Cornman, J.; Romano, D.; Huddleston, C.; Zimmerman, P.; et al. Impacts from control operations on a recreationally hunted feral swine population at a large military installation in Florida. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 7689–7697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McIllroy, J.C.; Saillard, R.J. The effect of hunting with dogs on the numbers and movements of feral pigs, Sus scrofa, and the subsequent success of poisoning exercises in Namadgi National Park, A.C.T. Wildl. Res. 1989, 16, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsan, A.; Spanò, S.; Tognoni, C. Management attempts of wild boar (Sus scrofa L.): First results and outstanding researches in Northern Apennines (Italy). IBEX J. Mt. Ecol. 1995, 3, 219–221. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni della Stella, R.; Calvoi, F.; Burrini, L. The wild boar management in a province of Central Italy. IBEX J. Mt. Ecol. 1995, 3, 213–216. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni della Stella, R.; Calvoi, F.; Burrini, L. Wild boar management in an area of southern Tuscany (Italy). IBEX J. Mt. Ecol. 1995, 3, 217–218. [Google Scholar]

- Fruziński, B.; Łabudzki, L. Management of wild boar in Poland. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2002, 48, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, T.; Kamenov, P.; Stefanov, D.; Depner, K. Trapping as an alternative method of eradicating classical swine fever in a wild boar population in Bulgaria. Rev. Sci. Tech. OIE 2011, 30, 911–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Geisser, H.; Reyer, H.-U. Efficacy of hunting, feeding, and fencing to reduce crop damage by wild boars. J. Wildl. Manag. 2004, 68, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briedermann, L. Jagdmethoden beim Schwarzwild und ihre Effektivität. Beitr. Jagd-und Wildforschung 1977, 10, 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, C.; Alexandre, N.; Fernandez-Llário, P.; Santos, P. Wild boar (Sus scrofa) harvesting using the espera hunting method: Side effects and management implications. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2010, 56, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keuling, O.; Stier, N.; Roth, M. How does hunting influence activity and spatial usage in wild boar Sus scrofa L.? Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2008, 54, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodeikat, G.; Pohlmeyer, K. Escape movements of family groups of wild boar Sus scrofa influenced by drive hunts in Lower Saxony, Germany. Wildl. Biol. 2003, 9, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodeikat, G.; Pohlmeyer, K. Impact of drive hunts on daytime resting site areas of wild boar family groups (Sus scrofa L.). Wildl. Biol. Pract. 2007, 3, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scillitani, L.; Monaco, A.; Toso, S. Do intensive drive hunts affect wild boar (Sus scrofa) spatial behaviour in Italy? Some evidences and management implications. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2010, 56, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, D.; Fournier, P. Effect of shooting with hounds on home range size of Wild Boar (Sus scrofa L.) groups in Mediter-ranean habitat. IBEX J. Mt. Ecol. 1995, 3, 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Thurfjell, H.; Spong, G.; Ericsson, G. Effects of hunting on wild boar (Sus scrofa L.) behaviour. Wildl. Biol. 2013, 19, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elliger, A.; Linderoth, P.; Pegel, M.; Seitler, S. Ergebnisse einer landesweiten Befragung zur Schwarzwildbewirtschaftung. WFS-Mitteilungen 2001, 5, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Liebl, T.; Elliger, A.; Linderoth, P. Aufwand und Erfolg der Schwarzwildjagd in einem stadtnahen Gebiet. WFS-Mitteilungen 2005, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Quirós-Fernández, F.; Marcos, J.; Acevedo, P.; Gortázar, C. Hunters serving the ecosystem: The contribution of recreational hunting to wild boar population control. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2017, 63, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzón, A.; Bento, P. An analysis of the hunting pressure on wild boar (Sus scrofa) in the Trás-os-Montes region of Northern Portugal. Galemys 2004, 16, 253–262. [Google Scholar]

- Tsachalidis, E.P.; Hadjisterkotis, E. Wild boar hunting and socioeconomic trends in Northern Greece, 1993–2002. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2008, 54, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luskin, M.; Christina, E.D.; Kelley, L.C.; Potts, M.D. Modern Hunting Practices and Wild Meat Trade in the Oil Palm Plantation-Dominated Landscapes of Sumatra, Indonesia. Hum. Ecol. 2013, 42, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumendjel, F.Z.; Hajji, G.E.M.; Valqui, J.; Bouslama, Z. The Hunting Trends of Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) Hunters in Northeastern Algeria. Wildl. Biol. Pract. 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Rosa, C.A.; Wallau, M.O.; Pedrosa, F. Hunting as the main technique used to control wild pigs in Brazil. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2018, 42, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, G.; Kanzaki, N. Wild Boar Hunters Profile in Shimane Prefecture, Western Japan. Wildl. Biol. Pract. 2005, 1, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keuling, O.; Stier, N.; Roth, M. Annual and seasonal space use of different age classes of female wild boar Sus scrofa L. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2008, 54, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M.; Koike, F.; Momose, H.; Mihira, T.; Uematsu, S.; Ohtani, T.; Sekiyama, K. Forecasting the range expansion of a re-colonising wild boar Sus scrofa population. Wildl. Biol. 2012, 18, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blumstein, D.T.; Berger-Tal, O. Understanding sensory mechanisms to develop effective conservation and management tools. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2015, 6, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toïgo, C.; Servanty, S.; Gaillard, J.M.; Brandt, S.; Baubet, E. Disentangling natural fom hunting mortality in an intensively hunted wild boar population. J. Wildl. Manag. 2008, 72, 1532–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, J.M.; Bonenfant, C.; Mysterud, A.; Gaillard, J.-M.; Csányi, S.; Stenseth, N.C. Temporal and spatial development of red deer harvesting in Europe: Biological and cultural factors. J. Appl. Ecol. 2006, 43, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajas, P. Évaluation des Facteurs Influençant le Succès de la Chasse pour Gérer le Sanglier (Sus scrofa): Comprendre les Relations entre l’Effort de Chasse, la Capturabilité et les Conditions de Chasse. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Montpellier, Montpellier, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Keuling, O.; Greiser, G.; Grauer, A.; Strauß, E.; Bartel-Steinbach, M.; Klein, R.; Wenzelides, L.; Winter, A. The German wildlife information system (WILD): Population densities and den use of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and badgers (Meles meles) during 2003–2007 in Germany. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2010, 57, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, J.E.; Beyerbach, M.; Strauss, E. Do hunters tell the truth? Evaluation of hunters’ spring pair density estimates of the grey partridge Perdix perdix. Wildl. Biol. 2012, 18, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strauß, E.; Grauer, A.; Bartel, M.; Klein, R.; Wenzelides, L.; Greiser, G.; Muchin, A.; Nösel, H.; Winter, A. The German wildlife information system: Population densities and development of European Hare (Lepus europaeus PALLAS) during 2002–2005 in Germany. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2007, 54, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NMELV. Aktuelle Jagdzeiten in Niedersachsen (konsolidierte Fassung) Stand: 25. Januar 2021 inkl. Verordnung zur Durch-führung des Nieders. Jagdgesetzes (DVO-NJagdG) vom 23. Mai 2008 (Nds. GVBl. S. 194), Zuletzt Geändert Durch Verordnung vom 18. Januar 2021 (Nds. GVBl. S. 24). Niedersächsisches Ministerium für Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Verbraucher-schutz. 2021. Available online: https://www.ml.niedersachsen.de/startseite/themen/wald_holz_jagd/jagd_in_niedersachsen/gesetze-und-andere-bestimmungen-rund-um-das-thema-jagd-und-jaeger-5137.html (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Keuling, O. Mittel zum Zweck—Schwarzwildbejagung an Kirrungen. Niedersächsischer Jäger 2015, 9, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- DWD. Deutscher Wetterdienst-Wetter und Klima-Klimadaten. Available online: https://www.dwd.de (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- NMELV. Niedersächsisches Ministerium für Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Verbraucherschutz—Jagd in Niedersachsen. Available online: http://www.ml.niedersachsen.de/portal/live.php?navigation_id=1415&article_id=5138&_psmand=7 (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Statistik-Portal. Gemeinsames Datenangebot der Statistischen Ämter des Bundes und der Länder. Available online: http://www.statistikportal.de/Statistik-Portal/ (accessed on 22 September 2020).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Happ, N. Hege und Bejagung des Schwarzwildes; Franckh-Kosmos GmbH & Co.: Stuttgart, Germany, 2002; p. 170. [Google Scholar]

- Cifuni, G.F.; Amici, A.; Contò, M.; Viola, P.; Failla, S. Effects of the hunting method on meat quality from fallow deer and wild boar and preliminary studies for predicting lipid oxidation using visible reflectance spectra. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2014, 60, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treyer, D.; Linderoth, P.; Liebl, T.; Pegel, M.; Weiler, U.; Claus, R. Influence of sex, age and season on body weight, energy intake and endocrine parameter in wild living wild boars in southern Germany. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2011, 58, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, E. Drückjagd auf Sauen; Neumann-Neudamm: Melsungen, Germany, 2004; p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbarth, E.; Ophoven, E. Bewegungsjagd auf Schalenwild; Franckh-Kosmos GmbH & Co.: Stuttgart, Germany, 2002; p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- Wölfel, H. (Ed.) Bewegungsjagden; Leopold Stocker Verlag: Graz-Stuttgart, Germany, 2003; p. 190. [Google Scholar]

- Happ, N. Hege und Bejagung des Schwarzwildes, 2nd ed.; Franckh-Kosmos GmbH & Co.: Stuttgart, Germany, 2007; p. 179. [Google Scholar]

- Genov, P.W.; Massei, G.; Kostova, W. Die Nutzung des Wildschweins (Sus scrofa) in Europa in Theorie und Praxis. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 1994, 40, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keuling, O.; Stier, N.; Roth, M. Commuting, shifting or remaining? Different spatial usage patterns of wild boar Sus scrofa L. in forest and field crops during summer. Mamm. Biol. 2009, 74, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WAHID. World Animal Health Information Database (WAHID) Interface. Available online: http://www.oie.int/wahis_2/public/wahid.php/Wahidhome/Home (accessed on 5 August 2014).

- Wieland, B.; Dhollander, S.; Salman, M.; Koenen, F. Qualitative risk assessment in a data-scarce environment: A model to assess the impact of control measures on spread of African Swine Fever. Prev. Vet. Med. 2011, 99, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hunting Method | Variable | Estimate | SE | p | R2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total single hunt | Intercept | 13.6851 | 2.3321 | 1.48 × 10−5 | 0.6326 | (1.18) = 30.99 |

| Year | −0.0065 | 0.0012 | 2.77 × 10−0.5 | |||

| Shot at bait (within single hunt) | Intercept | 28.8145 | 8.9892 | 0.0150 | 0.5896 | (1.7) = 10.06 |

| Year | −0.0142 | 0.0045 | 0.0157 | |||

| Total drive hunts | Intercept | −12.6370 | 2.2829 | 2.96 × 10−5 | 0.6407 | (1.18) = 32.1 |

| Year | 0.0064 | 0.0011 | 2.25 × 10−5 | |||

| Drive hunt in own hunting ground | Intercept | 2.4215 | 2.0680 | 0.257 | 0.0617 | (1.18) = 1.184 |

| Year | −0.0011 | 0.0010 | 0.291 | |||

| Comprehensive drive hunts | Intercept | −15.30 | 1.533 | 9.20 × 10−9 | 0.8491 | (1.18) = 101.2 |

| Year | 7.671 × 10−3 | 7.624 × 10−4 | 8.12 × 10−9 |

| Hunting Method | df | p | x2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single hunt at bait | 5 | <0.001 | 1492.0 |

| Single hut within fields | 5 | <0.001 | 830.0 |

| Accidential at hunt for other game from hide | 5 | <0.001 | 125.3 |

| stalking | 5 | <0.001 | 115.3 |

| Collective hide | 5 | <0.001 | 113.9 |

| Drive hunt within own hunting ground | 5 | <0.001 | 1317.5 |

| Comprehensive drive hunt | 5 | <0.001 | 1179.8 |

| Selective wild boar drives | 5 | <0.001 | 144.7 |

| During harvest | 5 | <0.001 | 189.8 |

| Small game drive hunt | 5 | <0.001 | 364.2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Keuling, O.; Strauß, E.; Siebert, U. How Do Hunters Hunt Wild Boar? Survey on Wild Boar Hunting Methods in the Federal State of Lower Saxony. Animals 2021, 11, 2658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11092658

Keuling O, Strauß E, Siebert U. How Do Hunters Hunt Wild Boar? Survey on Wild Boar Hunting Methods in the Federal State of Lower Saxony. Animals. 2021; 11(9):2658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11092658

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeuling, Oliver, Egbert Strauß, and Ursula Siebert. 2021. "How Do Hunters Hunt Wild Boar? Survey on Wild Boar Hunting Methods in the Federal State of Lower Saxony" Animals 11, no. 9: 2658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11092658

APA StyleKeuling, O., Strauß, E., & Siebert, U. (2021). How Do Hunters Hunt Wild Boar? Survey on Wild Boar Hunting Methods in the Federal State of Lower Saxony. Animals, 11(9), 2658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11092658