Interviews with Indian Animal Shelter Staff: Similarities and Differences in Challenges and Resiliency Factors Compared to Western Counterparts

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Animal Overpopulation in India

1.2. Occupational Health of Animal Shelter Staff

1.3. Research Gap and Study Rationale

1.4. Reflexivity Statement

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant Recruitment and Demographics

2.2. Ethics

2.3. Interviews and Data Collection

2.4. Data Processing

2.5. Theoretical Approach

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Shelter Challenges

3.1.1. High Intake

A. Pet Abandonment

B. Animal Overpopulation

A lot of Western NGOs… have quite different situations from what we have in India… We are very [different] in terms of having stray animals as a part of Indian community.

I know it’s not physically possible right now. But I just wish we could reach that stage where all of our dogs are spayed and neutered.

C. Seasonal Fluctuations

In the monsoon, healing takes so much time. In our animal birth control program, we have to release the dogs after like 10 days. Otherwise, in other seasons, we can release them after five days because healing processes [are] fast.

D. Animal Death

What happens is sometimes people feel that, you know, I don’t want to see those animals dying in front of my house or inside my house… [They say], ‘if I can afford to pay 5000 rupees, I will send her to a shelter, but I will not see the animal dying in the shelter. What happens in the shelter is not my problem’.

Our Indian ideology is that people think that we will pick up stray animals, put them in a cage and keep them there lifelong by giving them food. But that is not what we experience, no? That is not what we see. [We see] animals dying on us and, you know, it’s very painful at times.

You’re suddenly in a place with a hundred animals who are bleeding, who have wounds, who have maggots in their wounds, who are paralyzed, can’t walk, and whatnot. You’re suddenly in the middle of the room and you’re like, okay, I have to take care of them. It’s not that you are not alone, but you do feel alone.

3.1.2. Inadequate Funding

What happened is that the funding that we were supposed to get was all diverted to these COVID activities. A lot of big donors who said they are going to support us, at the last moment, they said, ‘right now I think it’s better to help people rather than animals.

A. Lack of Government Support

B. Government Policy

The Indian government brought a law saying that, you know, you have to streamline your foreign contribution. That took us a really long time to get all the work done, opening your bank account. So that was again a little painful.

C. Cultural and Religious Beliefs

Many times, people accuse us [of not doing our jobs]. We tell them that yes, we are an animal rescue, but we don’t have space to keep large animals. We can treat them, but we can’t keep them. It feels bad to tell them that.

3.1.3. Community Conflict

A. Rescuer Pressure

There was this one scenario I still remember. There was a dog with a broken pelvic bone—the pelvic was broken into almost three to four pieces. So, there was no way to repair that dog… But the rescuer said, ‘No, I don’t want to euthanize this animal.’ She said she’d like to take it to some other place. So, she took the dog, did the surgery, and the dog died on the table.

B. Resident Pushback

There are some people who do not like shelters… Sometimes, if we have to catch a dog, people will chase it away. They will not tell us where the dog is or if there is any problem or if they have to put in some effort.

C. Incorrect Community Care

And there are a lot, a lot of unethical feeders. So, yeah, rather than solving any issues, it creates a lot of problems: These people are keeping them with milk and rice and non-veg. Milk and rice will give them loose motion. So, the dogs are going to be pooping near all these peoples’ houses and no one will feel comfortable to clean it after feeding them. [People in the community] say: ‘You know what? You take them to your house, look out for them in the house. Don’t feed them here. We don’t want these dogs here. So, there’s a lot of conflict.

[And] you know, not like three meals a day, if you’re feeding them, feed them every alternate day, because the animals shouldn’t be dependent on one particular person. So, when you start feeding them on a daily basis, you are killing their survival instincts. You know, it becomes very difficult for the animals to survive.

3.2. Resiliency Factors

3.2.1. Flexibility and Prioritization

If I am doing some work, like if there is some priority case, then we handle them first. If someone’s clothes [i.e., bedding/bandages] are wet, we change them immediately. If they need hot water, we get it done… If someone hasn’t eaten, then we retry feeding them. If someone needs an extra egg, we give them to ensure that the feeding is complete. If someone’s clothing is dirty, then we change those.

I am that sort of person who ends up taking more on her plate than she can manage, even if it’s just going and checking up on somebody and spending 15 min there and I’m like ‘Oh god I could do something else!’, but that was important for me at that particular point in time.

No ma’am, we don’t have an X-ray machine. We go to a private clinic for those. There are some in [shelter city]. We have a CBC [Complete Blood Count] machine now. Any other biochemical tests are done in private clinics.

3.2.2. Co-Worker Support

A. Collaboration

So, nine hours of working plus like about two hours of traveling every day… It almost consumes my entire life. So, it’s like, my coworkers are the entire family and friends I have, my life is very sad [laughs].

If things are being changed then, I want them to understand that it’s for the bigger animal welfare picture. I try to explain to them why a certain decision is being made. Or if I’m scheduling them somewhere, then why is it so important, why them and not somebody else.

[I try to be] emotionally available for [new staff], because this [work] is so overwhelming… So, we try to gradually and slowly move them forward, and also be there and try and talk to them as to how they feel about it. I’m always trying to always find a balance where people can be able to express themselves and not get overwhelmed.

B. Equity and Safe Space

A lot of women that we get from the local villages have so much responsibility. They need to go back home and cook for their husbands. And sometimes they are not in the best situations. So, I really want to make these women feel more comfortable, not just in their workspace. But also, that it’s okay to say, ‘I’m not in a good place at home’.

If they’re going through something at their home place and you see that someone is down, like their energies are not as they used to be, we try to talk to them sometimes and see if we can help them out sometimes. Because it’s already too much to go through in the workplace—we are continuously stressed and you’re working nine hours a day. And then you go back home, and you have another issue.

I would say about 35 to 40% women and then the rest of them are men. It’s still predominantly men, but the shelter area is handled by women. [Name omitted] and [name omitted] two of our very strong women, they’re like the best caregivers that we have. Any new staff who enters the shelter, irrespective of their gender, needs to know that both of them are their bosses.

It’s also important to make them feel empowered. You are working. It’s you who is running the family. You are as independent as a man out there. So don’t, in any area, feel like you don’t do enough or feel like you are obliged to something.

3.2.3. Duty of Care

Me and my husband, daily we feed around 30 dogs. After we come back [from work], all the dogs are there. ‘When they come, when they come!’ They are waiting for their meal [laughs].

Yes, I feed them sometimes. For example, if I come across some dogs on the road and they approach me, I give them something. And if I know some dog, especially the dogs suffering from mange, you see a lot of mange-infested dogs around, so for treating them I usually put the tablets in some food and give it.

When I return, they get very happy. Sometimes they start fighting on seeing me or during feeding. They otherwise usually don’t fight among themselves… The moment they see me, they come to me running.

I have made them different kennels, so they stay in their kennels. Every day I pick up their poop and all that stuff because I’m used to it, because I work in an NGO and it’s my daily work.

To be very, very honest, I don’t feed any animals in my neighborhood. The reason is because, what happens is when I start feeding them people will start asking me or there have been cases where people will dump animals into my house. So, when they know that I’m associated with an association like this, they’ll be like you know what, take away this dog. So, it becomes a huge problem for me and for my family members.

People will ask you for medication, people will ask you for breed dogs, where do you get it, what do you do, how to get rid of this dog, cat. Answering all of these queries sometimes is really very stressful.

3.2.4. Understanding Animal Needs

A. Unrestricted Movement

Sometimes if we get them adopted, then they [the dog] starts wondering, why have I been restricted. For example, if we are suddenly asked to leave our house and start staying somewhere else, we will also feel odd and face issues.

Abandoned dogs cannot survive outside. They have no idea how to walk on the road, where to get food, water. They have no idea about anything. So, we should definitely try from our end to find them homes, good homes.

B. Autonomy

My [community] dogs have the best living situation as then they can go around and chase whoever they want. My home is forever open for them, so they can walk in whenever they want, and they can walk out wherever.

We don’t tie up those dogs, so they roam around. We have a lot of open space here. They know they will get food in the evening. They come back at that time.

I think these dogs can be kept at home, but they are street dogs. They should be allowed to roam out as well as allowed to stay inside the house. It shouldn’t happen that the dog is kept inside the house 24 × 7 and only sees the humans of that house. They should mix with others too.

C. Community Care

Some dogs may be taken care of by the locals. If something is wrong with them, the medicines are handed over to their local caretakers. Then there is no need to send them to the shelter… We need to make the local people aware of ABC and sterilization and that they can go to any shelter/NGO to get it done. Or if they are having trouble, then they can gather a few people for help and go to a government hospital and get that done.

I absolutely disagree to say that if they’re living on the streets, then they don’t have a good life if they have people in the community to take care of them. As long as these dogs on the street are community dogs, dogs that the entire community takes care of. I don’t see an issue in it.

If a community does decide to take care of these dogs, they don’t have to take care of like a hundred dogs. They know that these nine dogs will stay in my lane. So, they will develop a relationship with these dogs because they stay there, and they know these dogs. They know, this one eats a lot. You know all those small details.

4. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McCrea, R.C. The Humane Movement: A Descriptive Survey; The Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Rowan, A.; Kartal, T. Dog population & dog sheltering trends in the United States of America. Animals 2018, 8, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Rowan, A.N.; Williams, J. The success of companion animal management prrams: A Review. Anthrozoös 1987, 1, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, K. The biopolitics of animal being and welfare: Dog control and care in the UK and India. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2013, 38, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. South Asia. In Global Economic Prospects; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.K. Population ecology of free-ranging urban dogs in West Bengal, India. Acta Theriol. 2010, 46, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massei, G.; Fooks, A.R.; Horton, D.L.; Callaby, R.; Sharma, K.; Dhakal, I.P.; Dahal, U. Free-roaming dogs in Nepal: Demographics, health and public knowledge, attitudes and practices. Zoonoses Public Health 2017, 64, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.H.; Hampson, K.; Fahrion, A.; Abela-Ridder, B.; Nel, L.H. Difficulties in estimating the human burden of canine rabies. Acta Trop. 2017, 165, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, S.; Vanak, A.T.; Nouvellet, P.; Donnelly, C.A. Rabies as a public health concern in India: A historical perspective. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 5, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Animal Birth Control (Dogs) Rules, 2001 (India). Available online: https://bombayhighcourt.nic.in (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Agnihotram, R. An overview of occupational health research in India. Indian J. Indig. Med. 2005, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard Operating Procedures for Sterilization of Stray Dogs under the Animal Birth Control Program. (Animal Welfare Board of India). 2009. Available online: http://www.awbi.in/ (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Arluke, A.; Sanders, C.R. The institutional self of shelter workers. In Regarding Animals; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1996; pp. 82–106. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, E.M.; LaLonde, C.M.; Reese, L.A. Compassion fatigue in animal care workers. Traumatology 2020, 26, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rank, M.G.; Zaparanick, T.L.; Gentry, J.E. Nonhuman animal care compassion fatigue: Training as treatment. Best Pract. Ment. Health Int. J. 2009, 5, 40–61. [Google Scholar]

- Andrukonis, A.; Hall, N.J.; Protopopova, A. The impact of caring and killing on physiological and psychometric measures of stress in animal shelter employees: A pilot study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrukonis, A.; Protopopova, A. Occupational health of animal shelter employees by live release rate, shelter type, and euthanasia-related decision. Anthrozoös 2020, 33, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, B.E.; Rogelberg, S.G.; Carello Lopina, E.; Allen, J.A.; Spitzmüller, C.; Bergman, M. Shouldering a silent burden: The toll of dirty tasks. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 597–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, C.L.; Spitzmuller, C.; Rogelberg, S.G.; Walker, A.; Schultz, L.; Clark, O. Employee reactions and adjustment to euthanasia-related work: Identifying turning-point events through retrospective narratives. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2004, 7, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, P.; Rohlf, V. Perpetration-induced traumatic stress in persons who euthanize nonhuman animals in surgeries, animal shelters, and laboratories. Soc. Anim. 2005, 13, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N. Animal shelter emotion management: A case of in situ hegemonic resistance? Sociology 2010, 44, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schabram, K.; Maitlis, S. Negotiating the challenges of a calling: Emotion and enacted sensemaking in animal shelter work. AMJ 2017, 60, 584–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy-Gerlach, J.; Ojha, M.; Arkow, P. Social Workers in Animal Shelters: A Strategy Toward Reducing Occupational Stress among Animal Shelter Workers. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 734396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H.; Spector, P.E. Cross-cultural occupational health psychology. In Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology, 2nd ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 119–137. [Google Scholar]

- Blauner, B. Problems of editing in sociology. Qual. Sociol. 1987, 10, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-Y.; Boore, J.R. Translation and back-translation in qualitative nursing research: Methodological review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010, 19, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.; Blackman, D. A guide to understanding social science research for natural scientists. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 28, 1167–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levitt, A.L.; Gezinski, L.B. Compassion fatigue and resiliency factors in animal shelter workers. Soc. Anim. 2020, 28, 633–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, K.A.; Willis, D.G. Descriptive versus interpretive phenomenology: Their contributions to nursing knowledge. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Jones, J.; Turunen, H.; Snelgrove, S. Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2016, 6, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, I. Grounding Ground Theory: Guidelines for Qualitative Inquiry; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: San Diego, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J. Using conceptual depth criteria: Addressing the challenge of reaching saturation in qualitative research. Qual. Res. QR 2017, 17, 554–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthar, S.S.; Cicchetti, D.; Becker, B. Research on resilience: Response to commentaries. Child. Dev. 2000, 71, 573–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, A.; Ahmad, S.; Lee, E.J.; Morgan, J.E.; Singh, R.; Smith, B.W.; Southwick, S.M.; Charney, D.S. Coping and PTSD symptoms in Pakistani earthquake survivors: Purpose in life, religious coping and social support. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 147, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brintzinger, M.; Tschacher, W.; Endtner, K.; Bachmann, K.; Reicherts, M.; Znoj, H.; Pfammatter, M. Patients’ style of emotional processing moderates the impact of common factors in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy 2021, 58, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zawistowski, S.; Morris, J.; Salman, M.D.; Ruch-Gallie, R. Population dynamics, overpopulation, and the welfare of companion animals: New insights on old and new data. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 1998, 1, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenstrup, J.; Dowidchuk, A. Pet overpopulation: Data and measurement issues in shelters. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 1999, 2, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepper, M.; Kass, P.H.; Hart, L.A. Prediction of adoption versus euthanasia among dogs and cats in a California animal shelter. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2002, 5, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, L.C.; Bennett, P.C.; Coleman, G.J. What happens to shelter dogs? An analysis of data for one year from three Australian shelters. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2004, 7, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protopopova, A.; Gilmour, A.J.; Weiss, R.H.; Shen, J.Y.; Wynne, C.D.L. The effects of social training and other factors on adoption success of shelter dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 142, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, S.M.; Hupe, T.M.; Gandenberger, J.; Morris, K.N. Temporal trends in intake category data for animal shelter and rescue organizations in Colorado from 2008 to 2018. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2021, 260, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, K.F. The evolving role of triage and appointment-based admission to improve service, care and outcomes in animal shelters. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 809340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New, J.C.; Salman, M.D.; King, M.; Scarlett, J.M.; Kass, P.H.; Hutchison, J.M. Characteristics of shelter-relinquished animals and their owners compared with animals and their owners in U.Spet-owning households. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. JAAWS 2000, 3, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, J.B.; Young, I.; Lambert, K.; Dysart, L.; Nogueira Borden, L.; Rajić, A. A scoping review of published research on the relinquishment of companion animals. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2014, 17, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhan, M.; Bose, P. Canine counterinsurgency in Indian-occupied Kashmir. Crit. Anthropol. 2020, 40, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volsche, S.; Mohan, M.; Gray, P.B.; Rangaswamy, M. An exploration of attitudes toward dogs among college students in Bangalore, India. Animals 2019, 9, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janke, N.; Berke, O.; Klement, E.; Flockhart DT, T.; Coe, J.; Bateman, S. Effect of capacity for care on cat admission trends at the Guelph Humane Society, 2011-2015. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2018, 21, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protopopova, A.; Ly, L.H.; Eagan, B.H.; Brown, K.M. Climate change and companion animals: Identifying links and opportunities for mitigation and adaptation strategies. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2021, 61, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, S.C.; Yamamoto, M.; Thirumalai, K.; Giosan, L.; Richey, J.N.; Nilsson-Kerr, K.; Rosenthal, Y.; Anand, P.; McGrath, S.M. Remote and local drivers of Pleistocene South Asian summer monsoon precipitation: A test for future predictions. Sci Adv. 2021, 7, eabg3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, A.F.; Winefield, H.R.; Chur-Hansen, A. Occupational stress in veterinary nurses: Roles of the work environment and own companion animal. Anthrozoös 2011, 24, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, P.; Berry, J.; Macdonald, S. Animal shelters and animal welfare: Raising the bar. Can. Vet. J. 2012, 53, 893–896. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. Social finance funding model for animal shelter programs: Public–private partnerships using social impact bonds. Soc. Anim. Soc. Sci. Stud. Hum. Exp. Other Anim. 2018, 26, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, S.; Suar, D. Role of burnout in the relationship between job demands and job outcomes among Indian nurses. Vikalpa 2014, 39, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S. Accountable Handbook FCRA 2010: Theory and Practice: Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act, 2010, Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Rules, 2011; Account Aid India: New Delhi, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Di Russo, A.A. American nonprofit law in comparative perspective. Wash. Univ. Glob. Stud. Law Rev. 2011, 10, 39–86. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, M. The wisdom of crowds? groupthink and nonprofit governance. SSRN Electron. J. 2009, 62, 1179–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, J.D.; Carter, V.B. Factors influencing U.S charitable giving during the great recession: Implications for nonprofit administration. Adm. Sci. 2014, 4, 350–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milofsky, C.; Blades, S.D. Issues of accountability in health charities: A case study of accountability problems among nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 1991, 20, 371–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, A.S.; Nakao, T. Role of buffalo in the socioeconomic development of rural Asia: Current status and future prospectus. Anim. Sci. J. 2003, 74, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigateri, S. ‘Glory to the cow’: Cultural difference and social justice in the food hierarchy in India. South Asia J. South Asian Stud. 2008, 31, 10–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, A.; Miller, C. Holy cow! Beef ban, political technologies, and Brahmanical supremacy in Modi’s India. ACME Int. J. Crit. Geogr. 2019, 18, 835–874. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Graddy, E. Social Capital, volunteering, and charitable giving. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2008, 19, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCreanor, K.; McCreanor, S.; Utari, A. Connected and interconnected: Bali people and Bali dogs. In Dog’s Best Friend?: Rethinking Canid-Human Relations; Sorenson, J., Matsuoka, A., Eds.; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Corrieri, L.; Adda, M.; Miklósi, Á.; Kubinyi, E. Companion and free-ranging Bali dogs: Environmental links with personality traits in an endemic dog population of South East Asia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyastuti, M.D.W.; Bardosh, K.L.; Sunandar; Basri, C.; Basuno, E.; Jatikusumah, A.; Arief, R.A.; Putra, A.A.G.; Rukmantara, A.; Estoepangestie, A.T.S.; et al. On dogs, people, and a rabies epidemic: Results from a sociocultural study in Bali, Indonesia. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2015, 4, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyd, K.A.; Miller, C.A. Factors related to preferences for trap–neuter–release management of feral cats among Illinois homeowners. Wildfire 2010, 74, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Kreiner, G.E. Dirty work and dirtier work: Differences in countering physical, social, and moral stigma. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2014, 10, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopina, E.C.; Rogelberg, S.G.; Howell, B. Turnover in dirty work occupations: A focus on pre-entry individual characteristics. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 85, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonca, A.; D’Cruz, P.; Noronha, E. Identity work at the intersection of dirty work, caste, and precarity: How Indian cleaners negotiate stigma. Organization 2022, 13505084221080540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Rottenberg, J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biron, M.; van Veldhoven, M. Emotional labour in service work: Psychological flexibility and emotion regulation. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 1259–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoffe-Sharp, B. Administrative issues. In Shelter Medicine for Veterinarians and Staff; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Arora, P.; Bagga, S. Impact of job satisfaction on organizational performance among the employees working in a non-government organization (NGO) in Jaipur. Anwesh Roorkee 2019, 4, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.F. Dominance and affection. In Dominance and Affection; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, N.; Davies, C.A. My family and other animals: Pets as kin. Sociol. Res. Online 2008, 13, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthwick, F. Governing pets and their humans. Griffith Law Rev. 2009, 18, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraway, D.J. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness; Prickly Paradigm Press Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2003; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, J.G.; Brown, M.B. Piping Plovers Charadrius melodus and dogs: Compliance with and attitudes toward a leash law on public beaches at Lake McConaughy, Nebraska, USA. Wader Study Group Bull. 2014, 121, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Elder, G.; Wolch, J.; Emel, J. Race, place, and the bounds of humanity. Soc. Anim. 1998, 6, 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvides, N. Living with dogs: Alternative animal practices in Bangkok, Thailand. Anim. Stud. J. 2013, 2, 28–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, G.I.; Figueroa, M.; Connor, S.E.; Maliski, S.L. Translation barriers in conducting qualitative research with Spanish speakers. Qual. Health Res. 2008, 18, 1729–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Location [State] | Primary Animal Types | Total Number of Employees | Annual Animal Intake |

|---|---|---|---|

| Karnataka | Dogs, Cats, Rabbits | 44 | 400 |

| Himachal Pradesh | Dogs | # | 1500 |

| Rajasthan | Dogs, Cats, Cows, Bulls | 100 | 11,182 |

| Participant | Job Title | Gender | Age | State | Interview Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Manager | Woman | 31 | Rajasthan | English |

| P2 | Manager | Woman | 26 | Rajasthan | English |

| P3 | Manager | Man | 27 | Karnataka | English |

| P4 | Vet nurse | Man | 32 | Himachal Pradesh | Hindi |

| P5 | Vet nurse | Woman | 27 | Himachal Pradesh | Hindi |

| P6 | Vet nurse | Man | 28 | Rajasthan | Hindi |

| P7 | Caretaker | Man | 22 | Karnataka | Hindi |

| P8 | Caretaker | Woman | # | Karnataka | English |

| P9 | Caretaker | Man | 31 | Rajasthan | Hindi |

| P10 | Caretaker | Woman | 40 | Rajasthan | Hindi |

| Occupational Health |

|---|

| Can you describe your role and main responsibilities within (stated) organization? What does a typical day of work look like for you and what are your working hours? Can you talk about your relationship with your co-workers or supervisors? Do you generally find the workload manageable? [C.E] a What are the biggest challenges of your job? What are the most rewarding and exciting aspects of your job? What is the reaction of your friends and family to your job? |

| Shelter goals and practices |

| What are your shelter’s main goals? Does your shelter conduct low cost spay-neuter for street dogs that come into the shelter? [C.E] What are current challenges with the work your organization does? In your opinion, how different are the goals of Western animal NGOs from Indian animal NGOs? What changes would you like to see in your organization or Indian animal NGOs as a whole? |

| Perceptions of animal welfare |

| Do you feed community dogs/free-ranging dogs in your neighborhood? [C.E] In a ‘perfect world’, what would the lives of these dogs be like? Do you think we should attempt to get all dogs off the streets into homes or can street dogs have a good quality of life if numbers are controlled? [C.E] |

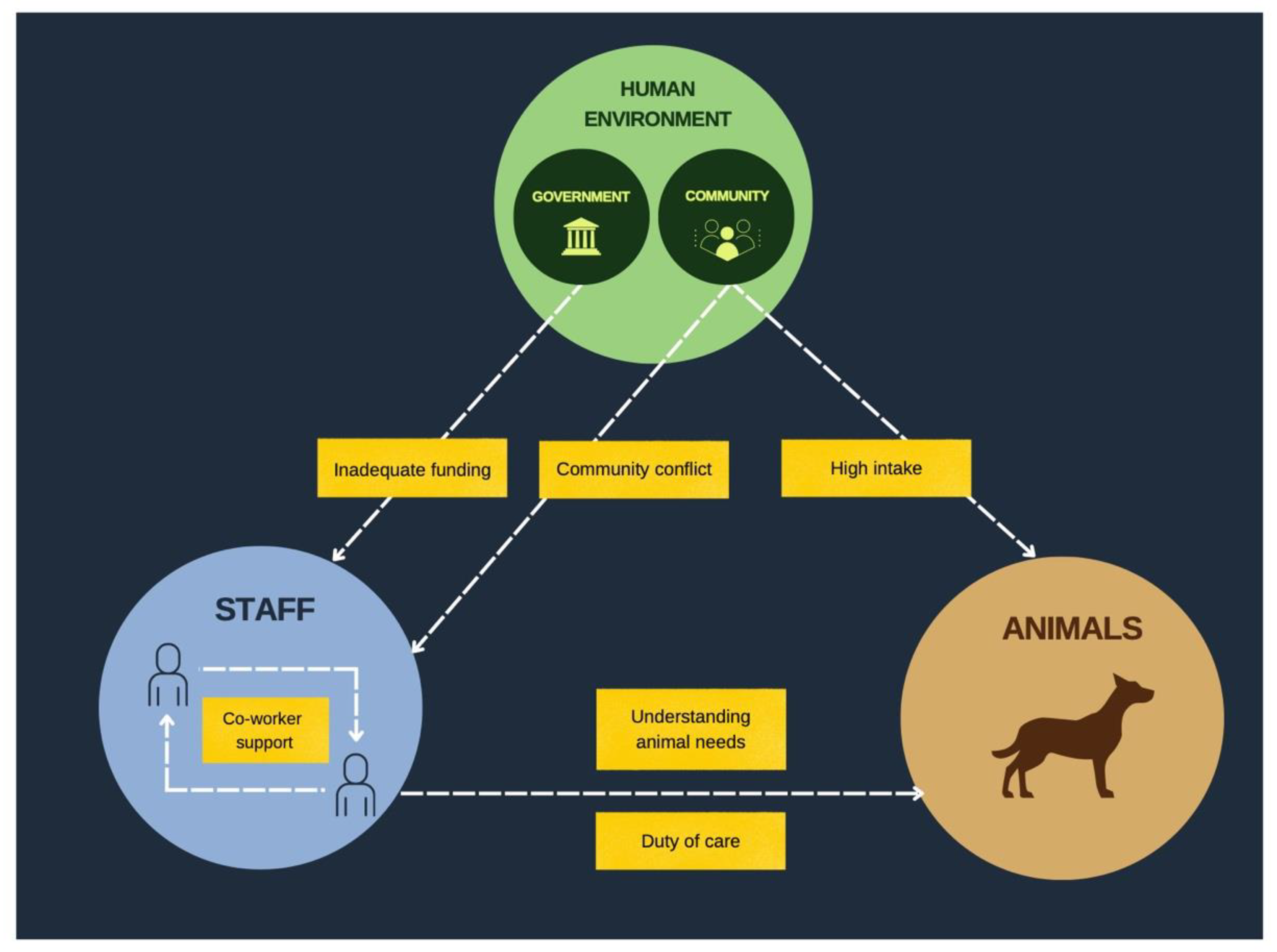

| Section 3.1 | Challenges | |

|---|---|---|

| Themes | Sub-Themes | |

| Section 3.1.1 | High intake |

|

| Section 3.1.2 | Inadequate funding |

|

| Section 3.1.3 | Community conflict |

|

| Section 3.2 | Resiliency Factors | |

| Themes | Sub-Themes | |

| Section 3.2.1 | Flexibility and prioritization | |

| Section 3.2.2 | Co-worker support |

|

| Section 3.2.3 | Duty of care | |

| Section 3.2.4 | Understanding animal needs |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Srinivasa, D.; Mondal, R.; Von Rentzell, K.A.; Protopopova, A. Interviews with Indian Animal Shelter Staff: Similarities and Differences in Challenges and Resiliency Factors Compared to Western Counterparts. Animals 2022, 12, 2562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12192562

Srinivasa D, Mondal R, Von Rentzell KA, Protopopova A. Interviews with Indian Animal Shelter Staff: Similarities and Differences in Challenges and Resiliency Factors Compared to Western Counterparts. Animals. 2022; 12(19):2562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12192562

Chicago/Turabian StyleSrinivasa, Deyvika, Rubina Mondal, Kai Alain Von Rentzell, and Alexandra Protopopova. 2022. "Interviews with Indian Animal Shelter Staff: Similarities and Differences in Challenges and Resiliency Factors Compared to Western Counterparts" Animals 12, no. 19: 2562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12192562

APA StyleSrinivasa, D., Mondal, R., Von Rentzell, K. A., & Protopopova, A. (2022). Interviews with Indian Animal Shelter Staff: Similarities and Differences in Challenges and Resiliency Factors Compared to Western Counterparts. Animals, 12(19), 2562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12192562