New Insight on Insulinoma Treatment in a Pet Rat—A Case Report

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

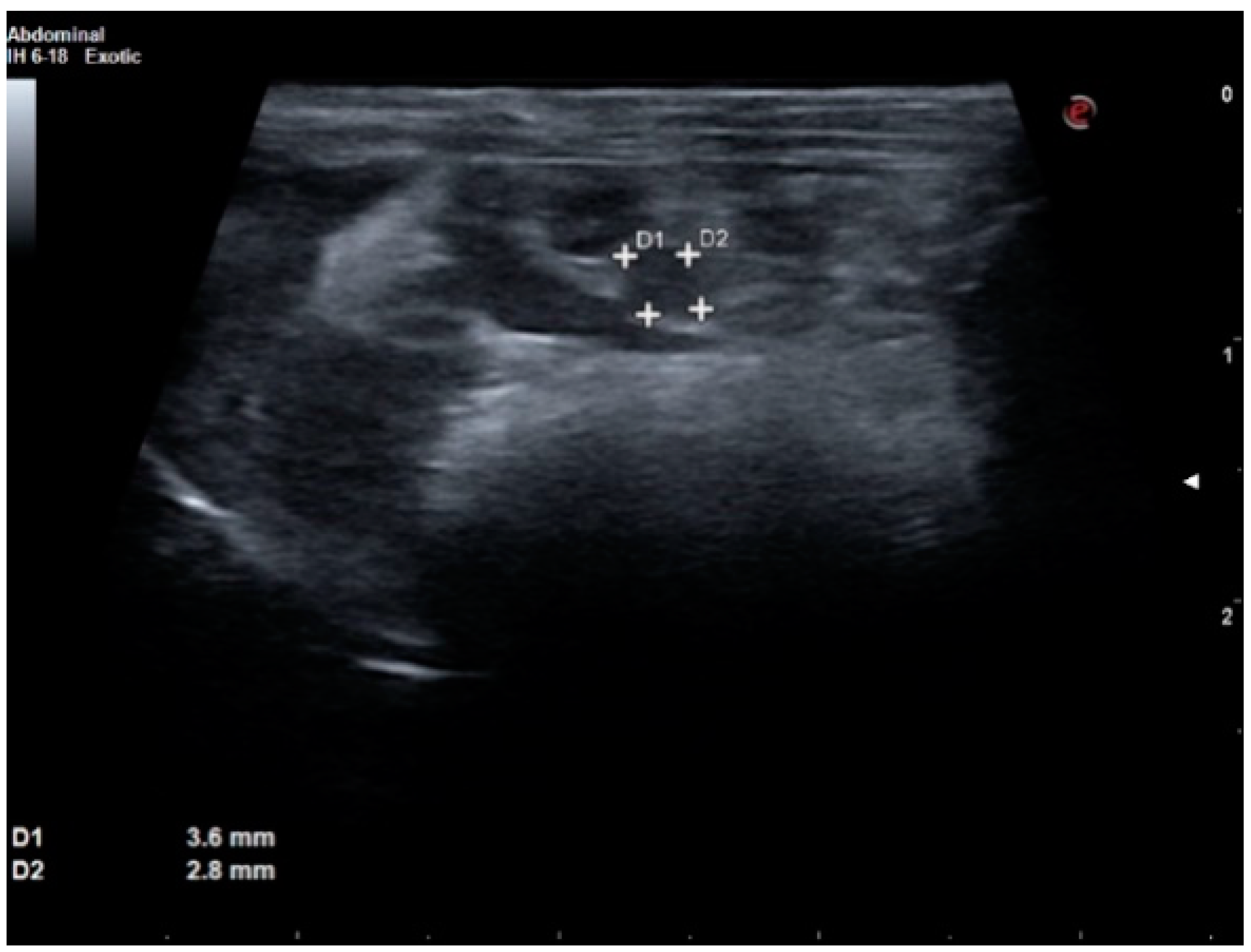

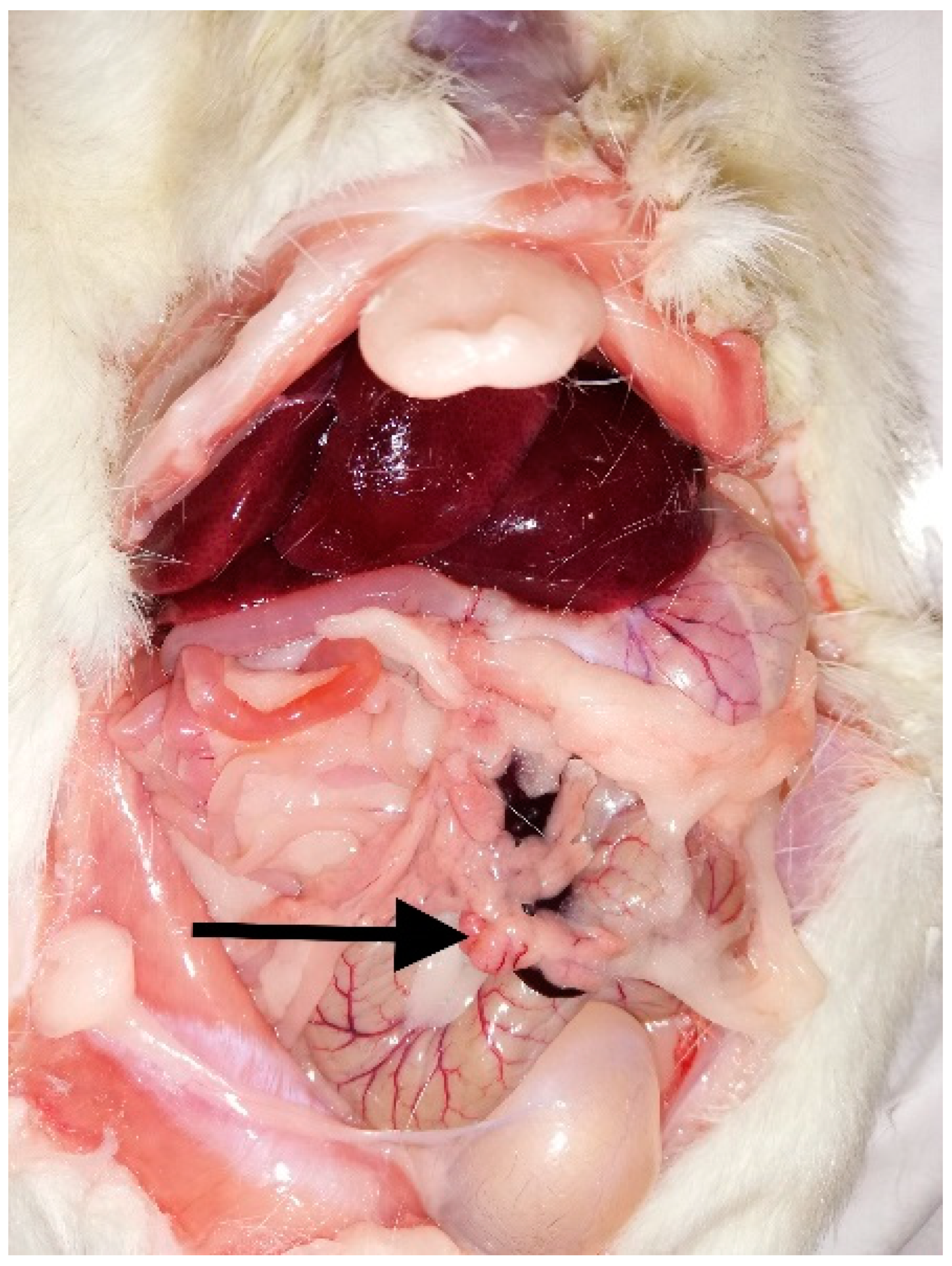

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, S. Advanced diagnostic approaches and current medical management of insulinomas and adrenocortical disease in ferrets (Mustela putorius furo). Vet. Clin. North Am. Exot. Anim. Pract. 2010, 13, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oglesbee, B.L. Blackwell’s Five-Minute Veterinary Consult: Small Mammal, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2011; pp. 126–127, 132–134. [Google Scholar]

- Quesenberry, K.E.; Orcutt, C.J.; Mans, C.; Carpenter, J.W. Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents, 4th ed.; Elsevier: St. Louis, MI, USA, 2021; pp. 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, M.; Tully, T. Current Therapy in Exotic Pet Practice; Elsevier: London, UK, 2016; pp. 294–296. [Google Scholar]

- Agúndez, M.G.; Velasco, C.I. Case report of a guinea pig (Cavia porcellus) with a surgically treated insulinoma. J. Exot. Pet. Med. 2020, 33, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, L.R.; Ravich, M.L.; Reavill, D.R. Diagnosis and treatment of an insulinoma in a guinea pig (Cavia porcellus). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2013, 242, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vannevel, J.Y.; Wilcock, B. Insulinoma in 2 guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus). Can. Vet. J. 2005, 46, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adissu, H.A.; Turner, P.V. Insulinoma and squamous cell carcinoma with peripheral polyneuropathy in an aged Sprague-Dawley rat. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2010, 49, 856–859. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Robertson, J.; Brand, J.; Blas-Machado, U.; Cohen, E.; Mayer, J. Spontaneous pancreatic islet cell adenoma with peripheral neuropathy in a pet rat (Rattus norvegicus). J. Exot. Pet. Med. 2019, 28, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.W.; Marion, C.J. Exotic Animal Formulary, 5th ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 459–493, 533–557. [Google Scholar]

- He, Q.; Su, G.; Liu, K.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, J.; Liu, L.; Jiang, Z.; Jin, M.; Xie, H. Sex-specific reference intervals of hematologic and biochemical analytes in Sprague-Dawley rats using the nonparametric rank percentile method. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chick, W.L.; Warren, S.; Chute, R.N.; Like, A.A.; Lauris, V.; Kitchen, K.C. Transplantable insulinoma in the rat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 628–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Flatt, P.R.; Tan, K.S.; Bailey, C.J.; Powell, C.J.; Swanston-Flatt, S.K.; Marks, V. Effects of transplantation and resection of a radiation-induced rat insulinoma on glucose homeostasis and the endocrine pancreas. Br. J. Cancer 1987, 54, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jensen, V.F.H.; Mølck, A.-M.; Heydenreich, A.; Jensen, K.J.; Bertelsen, L.O.; Alifrangis, L.; Andersen, L.; Søeborg, H.; Chapman, M.; Lykkesfeldt, J.; et al. Histopathological nerve and skeletal muscle changes in rats subjected to persistent insulin-induced hypoglycemia. J. Toxicol. Pathol. 2016, 29, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, K.; Yagihashi, S. Peripheral nerve pathology in rats with streptozotocin-induced insulinoma. Acta Neuropathol. 1996, 91, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, K.; Baba, M.; Suda, T. Peripheral neuropathy and microangiopathy in rats with insulinoma: Association with chronic hyperinsulinemia. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2003, 19, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stromberg, P.C.; Wilson, F.; Capen, C.C. Immunocytochemical demonstration of insulin in spontaneous pancreatic islet cell tumors of Fisher rats. Vet. Pathol. 1983, 20, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomhard, E. Frequency of spontaneous tumors in Wistar rats in 30-months studies. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 1992, 44, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K.M.; Poteracki, J. Spontaneous neoplasms in control Wistar rats. Fundam Appl. Toxicol. 1994, 22, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, A.J.; Andreu, M.; Greaves, P. Neoplasia and hyperplasia of pancreatic endocrine tissue in the rat: An immunocytochemical study. Vet. Pathol. 1986, 23, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Son, W.-C.h.; Bell, D.; Taylor, I.; Mowat, V. Profile of Early Occurring Spontaneous Tumors in Han Wistar Rats. Toxicol. Pathol. 2010, 38, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hajdu, A.; Herr, F.; Rona, G. The functional significance of a spontaneous pancreatic islet change in aged rats. Diabetologia 1968, 4, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turnbull, G.J.; Lee, P.N.; Roe, F.J. Relationship of body-weight gain to longevity and to risk of development of nephropathy and neoplasia in Sprague-Dawley rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1985, 23, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, K.P.; Soper, K.A.; Smith, P.F.; Ballam, G.C.; Clark, R.L. Diet, over-feeding and moderate dietary restriction in control Sprague–Dawley rats: I. Effects on spontaneous neoplasms. Toxicol. Pathol. 1995, 23, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molon-Noblot, S.; Keenan, K.P.; Coleman, J.B.; Hoe, C.M.; Laroque, P. The effects of ad libitum overfeeding and moderate and marked dietary restriction on age-related spontaneous pancreatic islet pathology in Sprague–Dawley rats. Toxicol. Pathol. 2001, 29, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, V.F.H.; Mølck, A.-M.; Chapman, M.; Alifrangis, L.; Andersen, L.; Lykkesfeldt, J.; Bøgh, I.B. Chronic Hyperinsulinaemic Hypoglycaemia in Rats Is Accompanied by Increased Body Weight, Hyperleptinaemia, and Decreased Neuronal Glucose Transporter Levels in the Brain. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 2017, 7861236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ohshima, J.; Nukada, H. Hypoglycaemic neuropathy: Microvascular changes due to recurrent hypoglycaemic episodes in rat sciatic nerve. Brain Res. 2002, 947, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidenius, P.; Jakobsen, J. Peripheral neuropathy in rats induced by insulin treatment. Diabetes 1983, 32, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bradley, A.E.; Bolon, B.; Butt, M.T.; Cramer, S.D.; Czasch, S.; Garman, R.H.; George, C.; Gröters, S.; Kaufmann, W.; Kovi, R.C.; et al. Proliferative and Nonproliferative Lesions of the Rat and Mouse Central and Peripheral Nervous Systems: New and Revised INHAND Terms. Toxicol. Path. 2020, 48, 827–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettinger, S.J.; Feldman, E.C.; Cote, E. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine Expert Consult, 8th ed.; Elsevier: St. Louis, MI, USA, 2010; pp. 1762–1767. [Google Scholar]

- Alan, I.S.; Alan, B. Side effects of glucocorticoids. In Pharmacokinetics and Adverse Effects of Drugs-Mechanisms and Risk Factors; Intechopen: London, UK, 2018; pp. 93–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christensson, C.; Thoren, A.; Lindberg, B. Safety of inhaled budesonide: Clinical manifestations of systemic corticosteroid-related adverse effects. Drug Saf. 2008, 31, 965–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, H.A.; Brueggen, J. Effects of somatostatin analogs on glucose homeostasis in rats. J. Endocrinol. 2012, 212, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Blood Results before Starting Treatment with Dexamethasone | Blood Results after 5 Weeks of Taking Dexamethasone | Reference Range According to Carpenter [10] and He et al. [11] * |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBC | 8.35 T/l | 8.42 T/l | 7–8 T/l |

| Ht | 43.2% | 48.1% | 35–45% |

| Hb | 15.4 g/dL | 16.5 g/dL | 12–18 g/dL |

| MCV | 51.7 fL | 57.1 fL | 55.21–64.8 fL * |

| MCH | 18.4 pg | 19.6 pg | 18.7–21.2 pg * |

| MCHC | 35.6 g/dL | 34.3 g/dL | 31.8–34.7 g/dL * |

| WBC | 3.11 G/L | 2.71 G/L | 5–23 G/L |

| neutrophils | 1.12 G/L | 1.98 G/L | 10–50% |

| lymphocytes | 1.58 G/L | 0.5 G/L | 50–70% |

| monocytes | 0.357 G/L | 0.220 G/L | 0–10% |

| eosinophils | 0.03 G/L | 0.003 G/L | 0–5% |

| basophils | 0.01 G/L | 0.003 G/L | 0–1% |

| PLT | 647 G/L | 465 G/L | 840–1240 G/L |

| ALT (GPT) | 32.0 U/L | 77.4 U/L | 20–92 U/L |

| AST (GOT) | 135.6 U/L | 186.6 U/L | |

| alpha-Amylase | 534.2 U/L | 488.9 U/L | |

| TP | 65.1 g/L | 73.7 g/L | 56–76 g/L |

| CK | 549 U/L | 382.0 U/L | |

| GLDH | 14.4 U/L | 98.6 U/L | |

| creatinine | 0.64 mg/dL | 0.81 mg/dL | 0.2–0.8 mg/dL |

| BUN | 27.38 mg/dL | 58.37 mg/dL | 15–21 mg/dL |

| glucose | 20.88 mg/dL | 94.5 mg/dL | 50–135 mg/dL |

| K+ | 5.57 mmol/L | 5.9 mmol/L | |

| Na+ | 146.5 mmol/L | 135–155 mmol/L | |

| Cl- | 104.7 mmol/L |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Godlewska, A.; Barszcz, K.; Orzechowska, A.; Małek-Sanigórska, A. New Insight on Insulinoma Treatment in a Pet Rat—A Case Report. Animals 2022, 12, 2783. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12202783

Godlewska A, Barszcz K, Orzechowska A, Małek-Sanigórska A. New Insight on Insulinoma Treatment in a Pet Rat—A Case Report. Animals. 2022; 12(20):2783. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12202783

Chicago/Turabian StyleGodlewska, Agata, Karolina Barszcz, Aleksandra Orzechowska, and Aleksandra Małek-Sanigórska. 2022. "New Insight on Insulinoma Treatment in a Pet Rat—A Case Report" Animals 12, no. 20: 2783. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12202783

APA StyleGodlewska, A., Barszcz, K., Orzechowska, A., & Małek-Sanigórska, A. (2022). New Insight on Insulinoma Treatment in a Pet Rat—A Case Report. Animals, 12(20), 2783. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12202783