Canine Socialisation: A Narrative Systematic Review

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

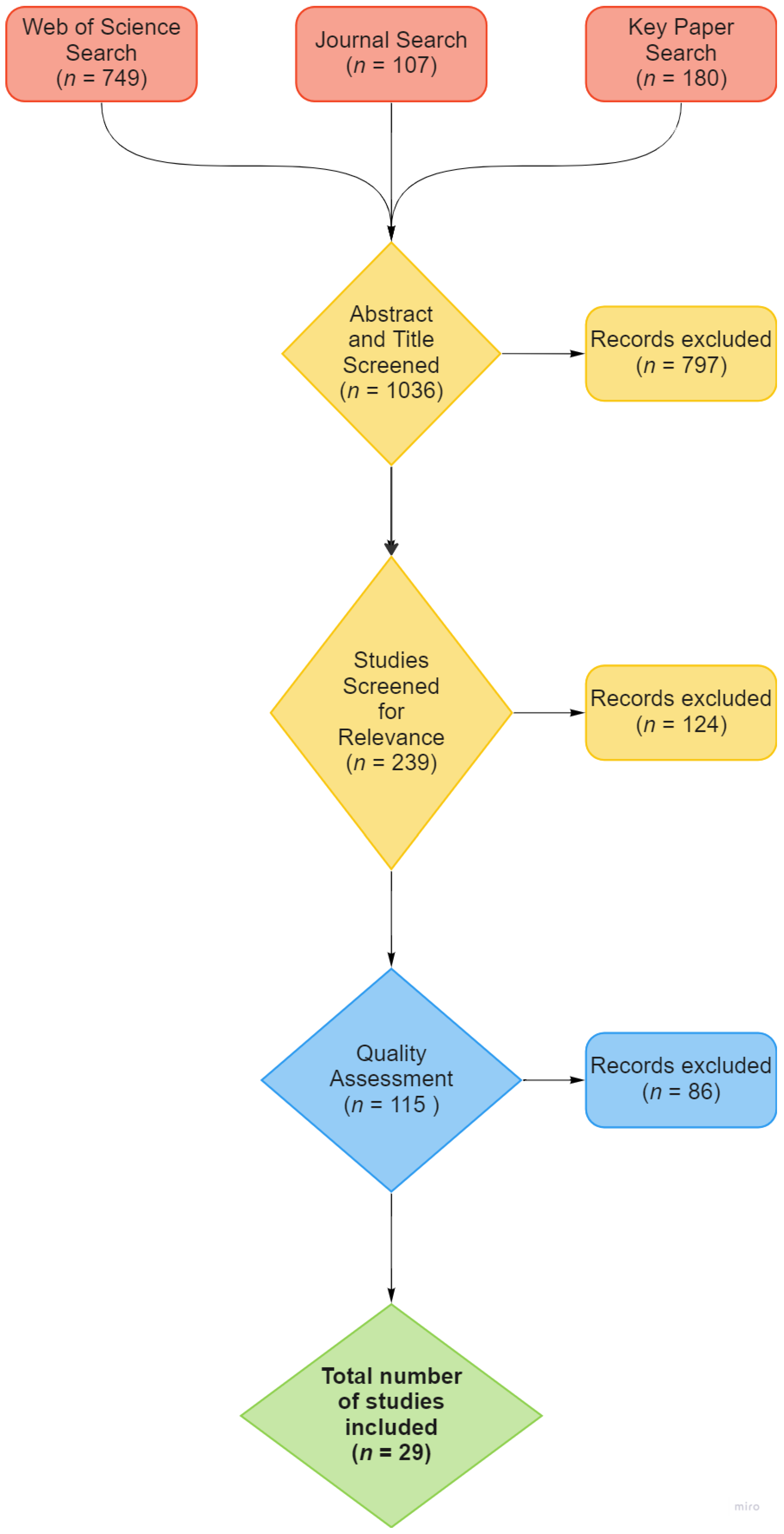

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Procedures

2.2. Classification of Results

2.3. Quality Assessment

- (1)

- Randomization: subjects allocated randomly to treatment groups. Although this is often not specified in methods sections, papers were excluded when experimental allocation was clearly biased.

- (2)

- Control: use of a suitable control group (with the exception of questionnaire-based studies).

- (3)

- Sample size: use of a sufficiently large sample size. Studies with a sample size of less than 5 experimental units (animals) per treatment group were discarded. Festing and Altman (2002) [50] state that the degrees of freedom for the error term used to test the effect of the variable should not be less than 10 [50].

- (4)

- Statistical methods: clear account of the statistical methods used to compare groups for all outcomes, use of appropriate statistical methods, and, where applicable, use of methods to account for non-independence of study subjects.

- (5)

- Exclusion of conference abstracts and proceedings: insufficient detail and information content for critical appraisal.

- (6)

- (7)

- Socialisation did not occur during the primary socialisation period (3–14 weeks). For example, Boxall (2004) [52] speaks of socialisation on dogs and its importance in laboratory animals, but the study focuses on adult dogs.

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Classic Studies

4.2. Socialisation Programs

4.3. Questionnaires

4.3.1. Canine Behavioural Assessment and Research Questionnaire (C-BARQ)

4.3.2. Non-C-BARQ

4.4. Puppy Classes

5. Future Directions

5.1. Assessing Outcomes

5.2. Other Periods That Influence Adult Dog Behaviour

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FEDIAF. EuropeanPetFood. Annual Report 2022, 22–23 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- PDSA. PDSA ANIMAL WELLBEING (PAW) REPORT 2021; Sunderland. 2022. Available online: https://www.pdsa.org.uk/get-involved/our-campaigns/pdsa-animal-wellbeing-report/paw-report-2021 (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- PFMA. Pawsitive PFMA Confirms Top Ten Pets PFMA News. Available online: https://www.pfma.org.uk/news/pawsitive-pfma-confirms-top-ten-pets (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Levine, S. Infantile experience and resistance to physiological stress. Science. 1957, 126, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateson, P. How do sensitive periods arise and what are they for? Anim. Behav. 1979, 27, 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmel, E.C.; Baker, E. The Effects of Early Experiences on Later Behavior: A Critical Discussion. In Early Experiences and Early Behavior; Simmel, E.C., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1980; pp. 3–13. ISBN 9780126440805. [Google Scholar]

- Bale, T.L.; Baram, T.Z.; Brown, A.S.; Goldstein, J.M.; Insel, T.R.; McCarthy, M.M.; Nemeroff, C.B.; Reyes, T.M.; Simerly, R.B.; Susser, E.S.; et al. Early Life Programming and Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 68, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bradshaw, J. Normal feline behaviour: … and why problem behaviours develop. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2018, 20, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Eath, R.B. Socialising piglets before weaning improves social hierarchy formation when pigs are mixed post-weaning. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 93, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdon, M.; Morrison, R.S.; Hemsworth, P.H. Rearing piglets in multi-litter group lactation systems: Effects on piglet aggression and injuries post-weaning. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 192, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peden, R.S.E.; Turner, S.P.; Boyle, L.A.; Camerlink, I. The translation of animal welfare research into practice: The case of mixing aggression between pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 204, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salazar, L.C.; Ko, H.-L.; Yang, C.-H.; Llonch, L.; Manteca, X.; Camerlink, I.; Llonch, P. Early socialisation as a strategy to increase piglets’ social skills in intensive farming conditions. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 206, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, J.E.; Camerlink, I.; Turner, S.P.; Farish, M.; Arnott, G. Socialisation and its effect on play behaviour and aggression in the domestic pig (Sus scrofa). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pedersen, V. Early experience with the farm environment and effects on later behaviour in silver Vulpes vulpes and blue foxes Alopex lagopus. Behav. Process. 1991, 25, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plyusnina, I.Z.Z.; Oskina, I.N.N.; Trut, L.N.N. An analysis of fear and aggression during early development of behaviour in silver foxes (Vulpes vulpes). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1991, 32, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahola, L.; Harri, M.; Kasanen, S.; Mononen, J.; Pyykönen, T. Effect of family housing of farmed silver foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in outdoor enclosures on some behavioural and physiological parameters. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2000, 80, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahola, L.; Harri, M.; Mononen, J.; Pyykönen, T.; Kasanen, S. Welfare of farmed silver foxes (Vulpes vulpes) housed in sibling groups in large outdoor enclosures. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2001, 81, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, V.; Moeller, N.H.H.; Jeppesen, L.L.L. Behavioural and physiological effects of post-weaning handling and access to shelters in farmed blue foxes (Alopex lagopus). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2002, 77, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.A.; Mason, G.; Pillay, N. Early environmental enrichment protects captive-born striped mice against the later development of stereotypic behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 135, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jago, J.; Krohn, C.; Matthews, L. The influence of feeding and handling on the development of the human–animal interactions in young cattle. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1999, 62, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krohn, C.C.; Jago, J.G.; Boivin, X. The effect of early handling on the socialisation of young calves to humans. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2001, 74, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, X.; Boissy, A.; Nowak, R.; Henry, C.; Tournadre, H.; Le Neindre, P. Maternal presence limits the effects of early bottle feeding and petting on lambs’ socialisation to the stockperson. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2002, 77, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krohn, C.C.; Boivin, X.; Jago, J.G. The presence of the dam during handling prevents the socialization of young calves to humans. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2003, 80, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, R.A.; Bradshaw, J.W.S. The effects of additional socialisation for kittens in a rescue centre on their behaviour and suitability as a pet. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 114, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.P.; Fuller, J.L. Genetics and the Social Behavior of the Dog, 1st ed.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA; London, UK, 1965; pp. 84–116. [Google Scholar]

- Serpell, J.; Duffy, D.L.; Jagoe, J.A. Becoming a dog: Early experience and the development of behavior. In The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behavior and Interactions with People, 2nd ed.; Serpell, J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 94–102. ISBN 1107024145. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.P.; Fuller, J.L. Genetics and the Social Behavior of the Dog, 1st ed.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA; London, UK, 1965; pp. 117–150. [Google Scholar]

- Case, L.P. The Dog: Its Behavior, Nutrition, and Health, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; ISBN 0-8138-1254-2. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, L.; Arnold, A.-M.K.; Goerlich-Jansson, V.C.; Vinke, C.M. The importance of early life experiences for the development of behavioural disorders in domestic dogs. Behaviour 2018, 155, 83–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McMillan, F.D. Behavioral and psychological outcomes for dogs sold as puppies through pet stores and/or born in commercial breeding establishments: Current knowledge and putative causes. J. Vet. Behav. 2017, 19, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.; Palmer, J. Dog bites. Br. Med. J. 2007, 334, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, E.N.; Jones, B.R.; O’Sullivan, K.; Hanlon, A.J. The management and behavioural history of 100 dogs reported for biting a person. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 114, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amat, M.; Camps, T.; Brech, S.L.; Manteca, X. Separation anxiety in dogs: The implications of predictability and contextual fear for behavioural treatment. Anim. Welf. 2014, 23, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulloch, J.S.P.; Owczarczak-Garstecka, S.C.; Fleming, K.M.; Vivancos, R.; Westgarth, C. English hospital episode data analysis (1998–2018) reveal that the rise in dog bite hospital admissions is driven by adult cases. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DAERA. Final Report of the Review of the Implementation of the Welfare of Animals Act NI 2011; DAERA: Belfast, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Van Uhm, D.P. Een Koppeling Tussen Theorie en Praktijk. 2004. Available online: http://www.vanuhmresearch.com/downloads/DP%20van%20Uhm%20-%20De%20Puppydossiers.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Zoltán, T.J. The Regulation of Animal Protection in Hungary; Károli Gáspár University: Budapest, Hungary, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Global Animal Law Association Slovakia Animal Laws in the Legislation Database. Available online: https://www.globalanimallaw.org/database/national/slovakia/ (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Dendoncker, P.-A.A.; De Keuster, T.; Diederich, C.; Dewulf, J.; Moons, C.P.H.H. On the origin of puppies: Breeding and selling procedures relevant for canine behavioural development. Vet. Rec. 2019, 184, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, F.D.; Serpell, J.A.; Duffy, D.L.; Masaoud, E.; Dohoo, I.R. Differences in behavioral characteristics between dogs obtained as puppies from pet stores and those obtained from noncommercial breeders. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2013, 242, 1359–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, C.L.; O’neill, D.G.; Belshaw, Z.; Pegram, C.L.; Stevens, K.B.; Packer, R.M.A. Pandemic Puppies: Demographic Characteristics, Health and Early Life Experiences of Puppies Acquired during the 2020 Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the UK. Animals 2022, 12, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaffenberger, C.J.; Scott, J.P. The relationship between delayed socialization and trainability in guide dogs. J. Genet. Psychol. 1959, 95, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.W.W.; Stelzner, D. Behavioural effects of differential early experience in the dog. Anim. Behav. 1966, 14, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.W.; Stelzner, D. Approach/withdrawal variables in the development of social behaviour in the dog. Anim. Behav. 1966, 14, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzack, R.; Burns, S.K. Neurophysiological effects of early sensory restriction. Exp. Neurol. 1965, 13, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklósi, A. Dog Behaviour, Evolution, and Cognition; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2007; ISBN 0191045713. [Google Scholar]

- Vaterlaws-Whiteside, H.; Hartmann, A. Improving puppy behavior using a new standardized socialization program. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 197, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Altman, D.G.; Booth, A.; et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (prisma-p) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’connor, A.M.; Sargeant, J.M.; Gardner, I.A.; Dickson, J.S.; Torrence, M.E.; Participants, M.; Dewey, C.E.; Dohoo, I.R.; Evans, R.B.; Gray, J.T.; et al. Preventive Veterinary Medicine and Journal of Swine Health and Production. Zoonoses and Public Health. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2010, 57, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Festing, M.F.W.; Altman, D.G. Guidelines for the Design and Statistical Analysis of Experiments Using Laboratory Animals. ILAR J. 2002, 43, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, T.; King, T.; Bennett, P. Puppy parties and beyond: The role of early age socialization practices on adult dog behavior. Vet. Med. Res. Rep. 2015, 6, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boxall, J.; Heath, S.; Bate, S.; Brautigam, J. Modern concepts of socialisation for Dogs: Implications for their behaviour, welfare and use in scientific procedures. ATLA Altern. Lab. Anim. 2004, 32, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, D.L.; Howell, T.; Benton, P.; Bennett, P.C. Socialisation, training, and help-seeking—Specific puppy raising practices that predict desirable behaviours in trainee assistance dog puppies. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 236, 105259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, N.D.; Craigon, P.J.; Blythe, S.A.; England, G.C.W.; Asher, L. An evidence-based decision assistance model for predicting training outcome in juvenile guide dogs. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hakanen, E.; Mikkola, S.; Salonen, M.; Puurunen, J.; Sulkama, S.; Araujo, C.; Lohi, H. Active and social life is associated with lower non-social fearfulness in pet dogs. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puurunen, J.; Hakanen, E.; Salonen, M.K.; Mikkola, S.; Sulkama, S.; Araujo, C.; Lohi, H. Inadequate socialisation, inactivity, and urban living environment are associated with social fearfulness in pet dogs. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González-Martínez, Á.; Martínez, M.F.; Rosado, B.; Luño, I.; Santamarina, G.; Suárez, M.L.; Camino, F.; de la Cruz, L.F.; Diéguez, F.J. Association between puppy classes and adulthood behavior of the dog. J. Vet. Behav. 2019, 32, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, J.; Arvelius, P.; Strandberg, E.; Polgar, Z.; Wiener, P.; Haskell, M.J. The interaction between behavioural traits and demographic and management factors in German Shepherd dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019, 211, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilder, M.B.H.; van der Borg, J.A.M.; Vinke, C.M. Intraspecific killing in dogs: Predation behavior or aggression? A study of aggressors, victims, possible causes, and motivations. J. Vet. Behav. 2019, 34, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaloupková, H.; Svobodová, I.; Vápeník, P.; Bartoš, L. Increased resistance to sudden noise by audio stimulation during early ontogeny in German shepherd puppies. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cutler, J.H.; Coe, J.B.; Niel, L. Puppy socialization practices of a sample of dog owners from across Canada and the United States. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2017, 251, 1415–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, L.; Blythe, S.; Roberts, R.; Toothill, L.; Craigon, P.J.; Evans, K.M.; Green, M.J.; England, G.C.W.W. A standardized behavior test for potential guide dog puppies: Methods and association with subsequent success in guide dog training. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2013, 8, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, N.D.; Craigon, P.J.; Blythe, S.A.; England, G.C.W.; Asher, L. Social rearing environment influences dog behavioral development. J. Vet. Behav. 2016, 16, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wormald, D.; Lawrence, A.J.; Carter, G.; Fisher, A.D. Analysis of correlations between early social exposure and reported aggression in the dog. J. Vet. Behav. 2016, 15, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiira, K.; Lohi, H. Early Life Experiences and Exercise Associate with Canine Anxieties. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Casey, R.A.; Loftus, B.; Bolster, C.; Richards, G.J.; Blackwell, E.J. Human directed aggression in domestic dogs (Canis familiaris): Occurrence in different contexts and risk factors. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 152, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, E.J.; Bradshaw, J.W.S.S.; Casey, R.A. Fear responses to noises in domestic dogs: Prevalence, risk factors and co-occurrence with other fear related behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2013, 145, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutsumi, A.; Nagasawa, M.; Ohta, M.; Ohtani, N. Importance of Puppy Training for Future Behavior of the Dog. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2012, 75, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arai, S.; Ohtani, N.; Ohta, M. Importance of Bringing Dogs in Contact with Children during Their Socialization Period for Better Behavior. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2011, 73, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, Y.K.; Lee, S.S.; Oh, S.I.; Kim, J.S.; Suh, E.H.; Oupt, K.A.; Lee, H.C.; Lee, H.J.; Yeon, S.C. Behavioral Reactivity of Jindo Dogs Socialized at an Early Age Compared with Non-Socialized Dogs. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2010, 72, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pluijmakers, J.J.T.M.; Appleby, D.L.; Bradshaw, J.W.S. Exposure to video images between 3 and 5 weeks of age decreases neophobia in domestic dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2010, 126, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batt, L.S.; Batt, M.S.; Baguley, J.A.; McGreevy, P.D. The Value of Puppy Raisers’ Assessments of Potential Guide Dogs’ Behavioral Tendencies and Ability to Graduate. Anthrozoos 2009, 22, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denenberg, S.; Landsberg, G.M. Effects of dog-appeasing pheromones on anxiety and fear in puppies during training and on long-term socialization. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2008, 233, 1874–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batt, L.; Batt, M.; Baguley, J.; McGreevy, P. The effects of structured sessions for juvenile training and socialization on guide dog success and puppy-raiser participation. J. Vet. Behav. 2008, 3, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, T.; Gaillard, C.; Gebhardt-Henrich, S.; Ruefenacht, S.; Steiger, A. External factors and reproducibility of the behaviour test in German shepherd dogs in Switzerland. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 94, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, M.M.; Jackson, J.A.; Line, S.W.; Anderson, R.K. Evaluation of association between retention in the home and attendance at puppy socialization classes. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2003, 223, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seksel, K.; Mazurski, E.J.; Taylor, A. Puppy socialisation programs: Short and long term behavioural effects. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1999, 62, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, D.G.; King, J.A.; Elliot, O. Critical period in the social development of dogs. Science 1961, 133, 1016–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.P.; Marston, M. Critical Periods Affecting the Development of Normal and Mal-Adjustive Social Behavior of Puppies. Pedagog. Semin. J. Genet. Psychol. 1950, 77, 25–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.; Serpell, J.A. Development and validation of a questionnaire for measuring behavior and temperament traits in pet dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2003, 223, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clarke, R.S.; Heron, W.; Fetherstonhaugh, M.L.; Forgays, D.G.; Hebb, D.O. Individual differences in dogs: Preliminary report on the effects of early experience. Can. J. Psychol. 1951, 5, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzack, R.; Thompson, W.R. Effects of early experience on social behaviour. Can. J. Psychol. Can. Psychol. 1956, 10, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzack, R.; Scott, T.H. The effects of early experience on the response to pain. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1957, 50, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, J.L. Experential Deprivation and Later Behaviour: Stress of emergence is postulated as the basis for behavioral deficits seen in dogs following isolation John. Science 1967, 158, 1645–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, T.L. Policy, Program and People: The Three P’s to Well-Being. Available online: https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=US9126455 (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Serpell, J.; Jagoe, J.A. Early experience and the development of behaviour. In The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, M.; Ottobre, J.; Ottobre, A.; Neville, P.; St-Pierre, N.; Dreschel, N.; Pate, J.L. Breed-dependent differences in the onset of fear-related avoidance behavior in puppies. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2015, 10, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, D.L.; Serpell, J.A. Effects of early rearing environment on behavioral development of guide dogs. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2009, 4, 240–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slabbert, J.; Odendaal, J.S. Early prediction of adult police dog efficiency—A longitudinal study. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1999, 64, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, J.A.A.; Hsu, Y. Development and validation of a novel method for evaluating behavior and temperament in guide dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2001, 72, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.D.; Mills, D.S. The effect of the kennel environment on canine welfare: A critical review of experimental studies. Anim. Welf. 2007, 16, 435–447. [Google Scholar]

- Riemer, S.; Müller, C.; Virányi, Z.; Huber, L.; Range, F. Validity of ealy behavioral assessments in dogs—A longitudinal study. J. Vet. Behav. 2014, 9, e10–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, K.; Hewison, L.; Wright, H.; Zulch, H.; Cracknell, N.; Mills, D. A spatial discounting test to assess impulsivity in dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 202, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.C.; Gosling, S.D. Temperament and personality in dogs (Canis familiaris): A review and evaluation of past research. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 95, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diederich, C.; Giffroy, J.M. Behavioural testing in dogs: A review of methodology in search for standardisation. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2006, 97, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiira, K.; Lohi, H. Reliability and validity of a questionnaire survey in canine anxiety research. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 155, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munch, K.L.; Wapstra, E.; Thomas, S.; Fisher, M.; Sinn, D.L. What are we measuring? Novices agree amongst themselves (but not always with experts) in their assessment of dog behaviour. Ethology 2019, 125, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wormald, D.; Lawrence, A.J.; Carter, G.; Fisher, A.D. Physiological stress coping and anxiety in greyhounds displaying inter-dog aggression. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 180, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prittie, J. Canine parvoviral enteritis: A review of diagnosis, management, and prevention. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2004, 14, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepita, M.E.; Bain, M.J.; Kass, P.H. Frequency of CPV Infection in Vaccinated Puppies that Attended Puppy Socialization Classes. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2013, 49, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, S.; Marshall-Pescini, S.; Pelosi, A.; Passalacqua, C.; Prato-Previde, E.; Valsecchi, P. Breed, sex, and litter effects in 2-month old puppies’ behaviour in a standardised open-field test. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Battaglia, C.L. Periods of Early Development and the Effects of Stimulation and Social Experiences in the Canine. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2009, 4, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majecka, K.; Pąsiek, M.; Pietraszewski, D.; Smith, C. Behavioural outcomes of housing for domestic dog puppies (Canis lupus familiaris). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2020, 222, 104899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, D.L.; Bradshaw, J.W.S.S.; Casey, R.A. Relationship between aggressive and avoidance behaviour by dogs and their experience in the first six months of life. Vet. Rec. 2002, 150, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnott, E.R.; Early, J.B.; Wade, C.M.; McGreevy, P.D. Environmental Factors Associated with Success Rates of Australian Stock Herding Dogs. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Doering, D.; Haberland, B.E.; Bauer, A.; Dobenecker, B.; Hack, R.; Schmidt, J.; Erhard, M.H. Behavioral observations in dogs in 4 research facilities: Do they use their enrichment? J. Vet. Behav. Appl. Res. 2016, 13, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Butler, S.; Douglas, C.; Serpell, J.A. Puppies from “puppy farms” show more temperament and behavioural problems than if acquired from other sources. In Proceedings of the Recent Advances in Animal Welfare Science V: UFAW Animal Welfare Conference, York, UK, 23 June 2016; UFAW The International Animal Welfare Science Society: York, UK, 2016; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Pirrone, F.; Pierantoni, L.; Pastorino, G.Q.; Albertini, M. Owner-reported aggressive behavior towards familiar people may be a more prominent occurrence in pet shop-traded dogs. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2016, 11, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, L.E.M.S.; Robinson, S.; Finch, J.; Buchanan-Smith, H.M. The influence of facility and home pen design on the welfare of the labWWory-housed dog. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2017, 83, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Rooy, D.; Thomson, P.C.; McGreevy, P.D.; Wade, C.M. Risk factors of separation-related behaviours in Australian retrievers. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 209, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, F.D.; Duffy, D.L.; Serpell, J.A. Mental health of dogs formerly used as “breeding stock” in commercial breeding establishments. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 135, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, M.E.; Roth, L.S.V.V.; Johnsson, M.; Wright, D.; Jensen, P. Human-directed social behaviour in dogs shows significant heritability. Genes, Brain Behav. 2015, 14, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Persson, M.E.; Sundman, A.-S.; Halldén, L.-L.; Trottier, A.J.; Jensen, P. Sociality genes are associated with human-directed social behaviour in golden and Labrador retriever dogs. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokinen, O.; Appleby, D.; Sandbacka-Saxén, S.; Appleby, T.; Valros, A. Homing age influences the prevalence of aggressive and avoidance-related behaviour in adult dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 195, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Odendaal, J.S.J. Early Separation of Pups. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. Van Die Suid Afrik. Vet. Ver. 1993, 64, 110. [Google Scholar]

- Pierantoni, L.; Albertini, M.; Pirrone, F. Prevalence of owner-reported behaviours in dogs separated from the litter at two different ages. Vet. Rec. 2011, 169, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slabbert, J.M.; Rasa, O.A.E. The effect of early separation from the mother on pups in bonding to humans and pup health. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. Van Die Suid Afrik. Vet. Ver. 1993, 64, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot, O.; Scott, J.P. The development of emotional distress reactions to separation, in puppies. J. Genet. Psychol. 1961, 99, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, J.A.; Duffy, D.L. Aspects of Juvenile and Adolescent Environment Predict Aggression and Fear in 12-Month-Old Guide Dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2016, 3, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.E.; Jordan, M.; Colon, M.; Shreyer, T.; Croney, C.C. Evaluating FIDO: Developing and pilot testing the Field Instantaneous Dog Observation tool. Pet Behav. Sci. 2017, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valsecchi, P.; Barnard, S.; Stefanini, C.; Normando, S. Temperament test for re-homed dogs validated through direct behavioral observation in shelter and home environment. J. Vet. Behav. 2011, 6, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, S.; Siracusa, C.; Reisner, I.; Valsecchi, P.; Serpell, J.A. Validity of model devices used to assess canine temperament in behavioral tests. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 138, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongrácz, P.; Miklósi, Á.; Kubinyi, E.; Topál, J.; Csányi, V.; Pongracz, P.; Miklosi, A.; Kubinyi, E.; Topal, J.; Csanyi, V. Interaction between individual experience and social learning in dogs. Anim. Behav. 2003, 65, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barrera, G.; Mustaca, A.; Bentosela, M. Communication between domestic dogs and humans: Effects of shelter housing upon the gaze to the human. Anim. Cogn. 2011, 14, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall-Pescini, S.; Virányi, Z.; Kubinyi, E.; Range, F. Motivational factors underlying problem solving: Comparing wolf and dog puppies’ explorative and neophobic behaviors at 5, 6, and 8 weeks of age. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bray, E.E.; Sammel, M.D.; Cheney, D.L.; Serpell, J.A.; Seyfarth, R.M. Effects of maternal investment, temperament, and cognition on guide dog success. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 9128–9133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brubaker, L.; Dasgupta, S.; Bhattacharjee, D.; Bhadra, A.; Udell, M.A.R. Differences in problem-solving between canid populations: Do domestication and lifetime experience affect persistence? Anim. Cogn. 2017, 20, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroshima, H.; Nabeoka, Y.; Hori, Y.; Chijiiwa, H.; Fujita, K. Experience matters: Dogs (Canis familiaris) infer physical properties of objects from movement clues. Behav. Process. 2017, 136, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fugazza, C.; Moesta, A.; Pogány, Á.; Miklósi, Á. Presence and lasting effect of social referencing in dog puppies. Anim. Behav. 2018, 141, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passalacqua, C.; Marshall-Pescini, S.; Barnard, S.; Lakatos, G.; Valsecchi, P.; Prato Previde, E. Human-directed gazing behaviour in puppies and adult dogs, Canis lupus familiaris. Anim. Behav. 2011, 82, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovcevic, A.; Mustaca, A.; Bentosela, M. Do more sociable dogs gaze longer to the human face than less sociable ones? Behav. Process. 2012, 90, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandurra, A.; Prato-Previde, E.; Valsecchi, P.; Aria, M.; D’Aniello, B.; D’Aniello, B. Guide dogs as a model for investigating the effect of life experience and training on gazing behaviour. Anim. Cogn. 2015, 18, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- D’Aniello, B.; Scandurra, A.; Prato-Previde, E.; Valsecchi, P. Gazing toward humans: A study on water rescue dogs using the impossible task paradigm. Behav. Process. 2015, 110, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentosela, M.; Wynne, C.D.L.; D’Orazio, M.; Elgier, A.; Udell, M.A.R. Sociability and gazing toward humans in dogs and wolves: Simple behaviors with broad implications. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 2016, 105, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aniello, B.; Scandurra, A. Ontogenetic effects on gazing behaviour: A case study of kennel dogs (Labrador Retrievers) in the impossible task paradigm. Anim. Cogn. 2016, 19, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marshall-Pescini, S.; Frazzi, C.; Valsecchi, P. The effect of training and breed group on problem-solving behaviours in dogs. Anim. Cogn. 2016, 19, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall-Pescini, S.; Rao, A.; Virányi, Z.; Range, F. The role of domestication and experience in ‘looking back’ towards humans in an unsolvable task. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Howell, T.J.; Bennett, P.C. Puppy power! Using social cognition research tasks to improve socialization practices for domestic dogs (Canis familiaris). J. Vet. Behav. 2011, 6, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, G.; Dzik, V.; Cavalli, C.; Bentosela, M. Effect of Intranasal Oxytocin Administration on Human-Directed Social Behaviors in Shelter and Pet Dogs. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victoria Dzik, M.; Barrera, G.; Bentosela, M. The relevance of oxytocin in the dog-human bond. Interdisciplinaria 2018, 35, 527–542. [Google Scholar]

- Willen, R.M.; Mutwill, A.; MacDonald, L.J.; Schiml, P.A.; Hennessy, M.B. Factors determining the effects of human interaction on the cortisol levels of shelter dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 186, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Staley, M.; Conners, M.G.; Hall, K.; Miller, L.J. Linking stress and immunity: Immunoglobulin A as a non-invasive physiological biomarker in animal welfare studies. Horm. Behav. 2018, 102, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwinski, V.H.; Smith, B.P.; Hynd, P.I.; Hazel, S.J. The influence of maternal care on stress-related behaviors in domestic dogs: What can we learn from the rodent literature? J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2016, 14, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, P.; Wilsson, E.; Jensen, P. Levels of maternal care in dogs affect adult offspring temperament. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foyer, P.; Wilsson, E.; Wright, D.; Jensen, P. Early experiences modulate stress coping in a population of German shepherd dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2013, 146, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guardini, G.; Mariti, C.; Bowen, J.; Fatjó, J.; Ruzzante, S.; Martorell, A.; Sighieri, C.; Gazzano, A. Influence of morning maternal care on the behavioural responses of 8-week-old Beagle puppies to new environmental and social stimuli. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 181, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gazzano, A.; Mariti, C.; Notari, L.; Sighieri, C.; McBride, E.A. Effects of early gentling and early environment on emotional development of puppies. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 110, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curley, J.P.; Jensen, C.L.; Mashoodh, R.; Champagne, F.A. Social influences on neurobiology and behavior: Epigenetic effects during development. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011, 36, 352–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schoon, A.; Berntsen, T.G. Evaluating the effect of early neurological stimulation on the development and training of mine detection dogs. J. Vet. Behav. 2011, 6, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariti, C.; Carlone, B.; Ricci, E.; Sighieri, C.; Gazzano, A. Intraspecific attachment in adult domestic dogs (Canis familiaris): Preliminary results. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 152, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feddersen-Petersen, D. The ontogeny of social play and agonistic behaviour in selected canid species. Bonn. Zool. Bull. 1991, 42, 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Bebak, J.; Beck, A.M. The effect of cage size on play and aggression between dogs in purpose-bred beagles. Lab. Anim. Sci. 1993, 43, 457–459. [Google Scholar]

- Bekoff, M. Play signals as puctuation: The structure of social play in canids. Behaviour 1995, 132, 319–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rooney, N.J.; Bradshaw, J.W.S. An experimental study of the effects of play upon the dog–human relationship. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2002, 75, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.K. Play behaviour during early ontogeny in free-ranging dogs (Canis familiaris). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2010, 126, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, G.M.; Albright, J.D.; Davis, K.M. Motivation, development and object play: Comparative perspectives with lessons from dogs. Behaviour 2016, 153, 767–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrkam, L.R.; Hall, N.J.; Haitz, C.; Wynne, C.D.L. The influence of breed and environmental factors on social and solitary play in dogs (Canis lupus familiaris). Learn. Behav. 2017, 45, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommerville, R.; O’Connor, E.A.; Asher, L.; O’Connor, E.A.; Asher, L. Why do dogs play? Function and welfare implications of play in the domestic dog. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 197, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.; Bauer, E.B.; Smuts, B.B. Partner preferences and asymmetries in social play among domestic dog, Canis lupus familiaris, littermates. Anim. Behav. 2008, 76, 1187–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, P.; Bjällerhag, N.; Wilsson, E.; Jensen, P. Behaviour and experiences of dogs during the first year of life predict the outcome in a later temperament test. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 155, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Sample Size | Breed/Type of Dog | Age of Animals | Hypotheses/Aims/Objectives | Methods | Main Findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Outcomes Assessed | |||||||

| Testing | Questionnaire | |||||||

| (Brand et al., 2022) [41] | 4369 (“Pandemic Puppies”) 1148 (“2019 Puppies”) | Various (Pet Dogs) | <16 wks 4 | Explore impact of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic on puppy early-life behaviour, socialisation/habituation experiences, and health. | X | X | Online, owner-completed survey; four sections including puppy demographics, health, behaviour and socialisation experiences. | Pandemic Puppies (aged <16 weeks) less likely than 2019 puppies to have attended puppy training classes or had visitors to their home. |

| (Mai et al., 2021) [53] | 231 (Puppy raisers and dogs) | Various (Assistance Dogs) | 3–25 mos 1 | Investigate relationships between puppy raisers’ practices, provision of various supports to puppy raisers, and puppy behavioural outcomes. | X | X | Online, puppy raiser completed survey. Questions included demographic information and raiser practices, support and puppy behaviour using the Puppy Training Supervisor Questionnaire (PTSQ 10; Harvey et al., 2017) [54]. | Puppy raisers that sought help for socialisation and training methods experienced better puppy outcomes. |

| (Hakanen et al., 2020) [55] | 13,700 (9613 fear fireworks, 9513 fear thunder, 6945 fear novel situations, 2932 fear surfaces and heights.) | Various (Pet Dogs) | Survey: 2 mos 1 to 18 yrs 2 | Identify environmental and demographic factors associated with non-social fearfulness. | X | X | Online, owner-completed questionnaire with background information and questions on seven canine anxiety traits. | Dogs that showed frequent non-social fear had experienced less socialisation during puppyhood. |

| (Puurunen et al., 2020) [56] | 5973 (fear of dogs, non-fearful dogs, 4806 vs. fearful dogs, 1167) 5932 (fear of strangers, 896, vs. non-fearful dogs, 5036) | Various (Pet dogs) | Survey: 2 mos 1 to 17 yrs 2 | Identify demographic and environmental factors associated with social fearfulness. | X | X | Online, owner filled. 7 main sections and demographic questions about socialisation. | Dogs with less socialisation during puppyhood more likely to fear other dogs and strangers. |

| (González-Martínez et al., 2019) [57] | 80 (32 attended puppy classes, 48 did not.) | Various (Pet dogs) | Puppy classes: 2 to 9 mos 1 Survey: ≥15 mos 1 | Determine effect of puppy classes on behavioural problems in adult dogs. | 1 hour per week of puppy classes over 6 weeks. | X | C-BARQ 3 one year after completion of puppy classes. | Both puppies and juveniles that attended classes had better scores for family-dog aggression, trainability, non-social fear, and touch sensitivity. |

| (Friedrich et al., 2019) [58] | 1041 dogs | German Shepherds | Survey: >2 yrs 2 | Identify behavioural traits characteristic of German Shepherds; analyse relation between behavioural traits and demographic/management factors including levels of socialisation received as a puppy. | X | X | C-BARQ 3 and lifestyle survey | High scores for socialisation as a puppy linked to lower scores for excitability and higher scores for stranger- directed interest and chasing. |

| (Schilder et al., 2019) [59] | 128 seized dogs; of 151 referred dogs in a clinical setting | Various (56% American Staffordshire/pit pull terrier type) | Veterinary examination: 9 mos 1 to 14 yrs 2 | Investigating behavioural characteristics of “dog-killing dogs” to identify causes and motivational backgrounds including levels of socialisation received during the primary socialisation period. | X | X | Data gathered during behavioural anamneses in a veterinary clinic of seized dogs. | Aggressive dogs had less socialisation than other types of dogs during the primary socialisation period. |

| (Chaloupková et al., 2018) [60] | 37 puppies (Treatment group = 19, control = 18). | Police dog breeds (Working dogs) | Audio stimulation: 16 to 32 days. | Analyse the effects of audio stimuli during early life. | Ordinary radio broadcasts played three times a day for 20-minute periods. | Exposure to a sudden noise, noise when alone, and loud distracting stimuli. | X | Treatment group puppies responded with a higher score, i.e., more positively, to the sudden noise than the control dogs. |

| (Cutler, Coe and Niel, 2017) [61] | 296 | Various (Pet dogs) | Surveys: < 20 wks 4 | Characterise owner-reported experience of puppies attending socialisation classes, and owners’ approaches to socialisation | Responses compared between owners that did and did not attend puppy classes. | X | Participants completed a survey at enrolment and again when puppies were 20 wks 4 of age. | Attendee puppies less likely than non-attendee puppies of to show signs of fear in response to noises. |

| (Vaterlaws-Whiteside and Hartmann, 2017) [47] | 33 (19 new socialisation program, 14 standard socialisation) | Guide dog breeds | Socialisation: 0 to 5 wks 4, PPA 5: 6 wks 4, PWQ 6: 8 mos 1 | Design and evaluate new, inexpensive socialisation program. | New socialisation programme vs. standard breeder socialisation programme. | X | Puppy Profiling Assessment (PPA 5; Asher et al., 2013) [62] Puppy Walking Questionnaire (PWQ 6; Harvey et al., 2016) [63] | Puppies receiving extra socialisation had significantly better scores for separation-related behaviour, distraction, general anxiety and body sensitivity at both 6 weeks and 8 months. |

| (Harvey et al., 2016) [63] | 224 | Guide dog breeds | PWQ 6: 5 and 8 mos 1 PWQ 6 and “Environmental Information” survey: 12 mos 1 | Explore how dogs’ home rearing environment will influence behavioural development. | X | X | Puppy Walking Questionnaire (PWQ 6; Harvey et al., 2016) [63] 11-item “Environmental Information” survey. | Dogs scored higher in energy level, excitability, and distractibility if raised with children, lower on energy level and distractibility with experienced carer, and lower on separation-related behaviour with more play with other dogs. |

| (Wormald et al., 2016) [64] | 783 | Various (Pet dogs) | Survey: 1 to 3 yrs 2 Acquired as puppies: <10 wks 4 | This retrospective questionnaire aimed to quantify the amount of and age at which pet dogs received early social exposure compared to the levels of interdog aggression. | X | X | Questionnaire with 5 sections: (1) dog background; (2) early environment; (3) social exposure experience; (4) current behaviour; (5) health. | Early exposure of puppies in public areas was negatively correlated with reduced inter-dog aggression in adult dogs. |

| (Tiira and Lohi, 2015) [65] | 3264 | Various (192 breeds) | Survey: 3 mos 1 to 15 yrs 2 | Investigate environmental factors linked to fear-related behaviours | X | X | Validated owner-filled questionnaire. | Fearful dogs had less socialisation experiences. |

| (Casey et al., 2014) [66] | 3897 | Various (Pet dogs) | Survey: 6 mos 1 to 17 yrs 2 | Estimate number of dogs showing aggression to people in three contexts (unfamiliar people on entering, or outside the house, and family members) Investigate risk factors for aggression. | X | X | Questionnaire with four sections. | Attendance at puppy classes reduced risk of aggression to unfamiliar people. |

| (Blackwell, Bradshaw and Casey, 2013) [67] | 3897 (postal survey) 383 (structured interview) | Various (Pet dogs) | Survey: 6 to 216 mos 1 | Investigate prevalence and characteristics of noise-associated fear; identify risk factors and any co-morbidity with separation-related behaviour and fear responses in other contexts. | X | X | Postal survey of dog owners to investigate general demographic factors, and structured interviews to gather more detailed information. | Early exposure to noises a risk factor for specific fears. |

| (Kutsumi, 2012) [68] | 142 (44 Puppy classes, 39 puppy parties, 27 adult classes, 32 no classes) | 31 breeds representing sporting, hound, terrier, toy, non-sporting, and herding demographics | Puppy classes: ~4 mos 1 | Clarify whether puppy socialisation and command training class prevented behaviour problems in dogs. | Puppy classes 1 h each week for 6 weeks; puppy parties 1 h each week for six weeks; adult class involved obedience lessons for 1 h each week for 6 weeks; no class group underwent no formal training. | Behaviour test evaluating response to commands, owner’s recall, separation, a response to novel stimulus and strangers. | C-BARQ 3 | Adult and puppy class dogs responded to commands better; puppy classes dogs had more positive responses to strangers. |

| (Arai, Ohtani and Ohta, 2011) [69] | 31 (10 dogs had experience of children during and after socialisation period, 11 dogs had experience after only, 10 dogs had no experience) | Various (13 breeds, pet dogs) | Dogs were initially acquired between birth and 12 mos 1. | Demonstrate how dogs’ contact with children during and after socialisation period influenced responses toward children. | Dogs that had contact with children during socialisation period; dogs that had contact with children after the socialisation period; dogs that seldom had contact with children. | Exposure of dogs to a novel child exhibiting three behaviours including calling the dogs name repeatedly whilst standing in front of the door, approaching the dog and calling the dogs name whilst running around it. | Questionnaire to ascertain levels of child exposure during socialisation period. | Dogs that had contact with children during and after the socialisation period showed no aggressive or excited behaviour towards children. Dogs that only had contact with children after the socialisation period showed some affinity behaviour but also aggressive, escape and excited behaviour when the child was active. Dogs with no exposure to children showed lots of aggressive behaviour and little affinity behaviour. |

| (Kim et al., 2010) [70] | 12 (6, Socialised and 6, non-socialised.) | Jindo (Laboratory dogs) | Treatment and baseline testing: 7 wks 4 Testing: 9, 11, 13 and 60 wks 4 | Determine whether socialised puppies showed different behavioural reactivity from non- socialised puppies. | Puppies assigned to a socialised group or a non-socialised group. | 5 behavioural tests. | X | Socialised Jindo puppies exhibited more intense playful reactivity towards novel stimuli and a dog at 9 weeks. There were no significant differences between the groups at 11, 13 or 60 weeks. |

| (Pluijmakers, Appleby and Bradshaw, 2010) [71] | Experiment 3: 28 (15 treatment, 13 Control) | Various commercially bred dogs (3 breeds) Maltese Terrier Boomer and Jack Russell Terrier. | Treatment: 3 to 5 wks 4 Testing: 51 to 61 days (Experiment 3) | Tested whether exposure to audio visual playback reduced fearful and increased exploratory behaviour | Experiment 3: Half of each litter 30 mins each day for 2 weeks, video footage and the other half acted as controls. Control: 30 mins each day for 2 weeks, blank screen | Testing at 36 days in a familiar environment and an unfamiliar environment with objects corresponding to those in the video footage and unfamiliar objects. | X | Puppies exposed to the video images were less fearful than the non-exposed puppies. The control puppies held their ears back between the partial and maximal position for significantly longer than the exposed puppies and also were more likely to exhibit a crouched posture. |

| (Batt et al., 2009) [72] | 111 | Guide dog breeds (Working dogs) | Survey: 13 mos 1 | Design a questionnaire that related puppy raisers’ reports to guide dog performance. | X | X | Modified C-BARQ 3 | Puppy raisers’ predictions of success and number of dogs in the household best predicted success in the guide dog training program. |

| (Denenberg and Landsberg, 2008) [73] | 45 (24 DAP, 21 placebo) | 2 large and 2 small breed groups (Laboratory dogs) | Puppy classes: 12 to 15 wks 4 | Evaluate effectiveness of DAP 8 in reducing fear and anxiety, and effects on training and socialisation. | Four groups of puppies in puppy classes: 2 large-breed groups (1 DAP 8 and 1 placebo group) and 2 small-breed groups (1 DAP 8 and 1 placebo group). | X | Classes lasted 8 weeks; owners completed questionnaire before and after each lesson. Follow-up telephone surveys on subsequent socialisation of puppies 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after classes ended. | Dogs in DAP 8 groups less fearful and anxious than placebo groups; DAP 8 groups displayed longer and more positive interactions between puppies, including play. |

| (Batt et al., 2008) [74] | 60 (20 training, 20 socialisation, 20 control) | Guide Dogs Breeds (Working dogs) | Treatment: 12 to 16 wks 4 Testing: 14 mos 1 | Explore whether training and socialisation improve success rates in guide dog program. | Training, socialisation, and control. | Success in Guide Dog programme. | X | Socialisation/training treatments did not influence success rate nor likelihood of puppy raisers raising another pup. |

| (Fuchs et al., 2005) [75] | 149 | German Shepherds (Pet dogs) | 1–2 yrs 2 | Investigate influence of external factors like socialisation, husbandry, training on results of behaviour test that focused on seven traits, self confidence, nerve stability, reaction to gunfire, temperament, hardness, sharpness, defense drive, and overall behaviour and compare test consistency after one year. | X | 30–40 min behavioural test exposing dogs to various stimuli (described in detail by Ruefenacht et al., (2002)). | Questionnaire covering husbandry, training, socialisation, and behaviour in certain situations, etc. before first test. After 1 year, 38 dogs tested again, alongside another, similar questionnaire. | Dogs from rescue shelters or with several previous owners received worse results in reaction to gunfire and “hardness”, which is defined as severity or ability to accept unpleasant perceptions without being deeply impressed afterwards. |

| (Duxbury et al., 2003) [76] | 248 (87, Humane Society socialisation classes, other socialisation classes, 132, no socialisation classes, 29) | Not specified Pet dogs | Treatment: 7 to 12 wks 4 Survey: 1 to 6.5 yrs 2 | Identify associations between retention of dogs in their adoptive homes and attendance at puppy socialisation classes (and other factors) | Puppies either underwent socialisation classes or did not. | X | Epidemiologic survey on adult dogs that were adopted as puppies from a humane society. | Higher retention for dogs that participated in Humane Society socialisation classes and were handled frequently as puppies. |

| (Seksel, Mazurski and Taylor, 1999) [77] | 58 (12, Socialisation plus Training S/T, 10, Socialisation, 13, Training, 12, Feeding and 11, Control) | Various (36 breeds) Pet dogs | Treatment and Testing: 6 to 16 wks 4 Survey: 4 to 6 mos 1 following the completion of the program, and before start of program. | Puppies that underwent socialisation hypothesised to be better behaved, score higher in the handling, social stimuli, and novel stimuli category. | S/T puppies attended Puppy Preschool class for 1 h; Training group received 10 mins 9 training per week; Socialisation group received only socialisation experiences; Feeding group given treats equal other groups; Control group attended the veterinary clinic for 15 mins 9 (All for 4 wks 4) | Battery of tests scored by four scales of social, novel, handling, and commands scores. | X | Puppies in the S/T and training groups received significantly higher ratings for their responses to commands at 2 and 4 weeks into the programme. No significant group effects on any other time-scales. |

| (Fox and Stelzner, 1966) [43] | 22 (8 control, 8 handled, and 6 partially socially isolated) | Not specified Laboratory dogs | Treatment: Birth to 5 wks 4 Testing: 5 wks 4 | Determine the effects of differential rearing on behaviour and development. | Handling carried out from one day until 5 wks 4 of age. Handling included light, sound and conspecific interactions. | Arena test Approach test Detour test | X | Handled puppies hyperactive, more exploratory, very sociable towards humans, and more dominant in social play. They also preformed best in the detour task. |

| (Freedman, King and Elliot, 1961) [78] | 34 (6 two weeks, 6 three weeks, 7 five weeks, 7 seven weeks, 3 nine weeks, 5 controls) | Cocker spaniels and beagles Laboratory dogs | Treatment: 2 to 14 wks 4 Testing: 14 wks 4 | Identify age when human contact most reduces withdrawal response at 14 wks 4 | Puppies taken for a week of socialisation at 2, 3, 5, 7 and 9 wks 4 of age. Controls remained in the field. | Handling test at 14 wks 4. | X | Puppies increasingly withdrew from humans if taken for socialisation after 5 wks 4 of age. If taken after 14 wks 4, normal human relationships could not be established. |

| (Pfaffenberger and Scott, 1959) [42] | 154 (40, 0–1 wks 4 in kennel. 22, 1–2 wks 4. 18, 2–3 wks 4, 3 or more wks 4. 30, controls and dogs which failed the initial puppy testing program from 8–12 wks 4. 124, puppies which passed the initial testing.) | Various (4 breeds) Guide dogs Working dogs | Treatment: 12 to 23 wks 4 | Identify factors affecting success rates of guide dogs. | Rehomed at 12 wks 4 or spent longer at kennel before rehoming (1–11 wks 4). | Success in guide dog training. | X | Dogs homed after 12 weeks passed training with approximate 90% success rate. Dogs placed in second week after the 12 weeks performed slightly poorer, but not significantly so. Dogs retained in kennel more than two wks 4 had more failures. |

| (Scott and Marston, 1950) [79] | 73 (20 observational data only, 53 both test and observational data) | Basenji, Beagle, Cocker spaniel, Dachshund, Shetland Sheep Dog and Wire-haired Fox Terrier. | Testing: 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15 wks 4. | Study whether development of social behaviour in puppies occurs during critical periods when experiences have long-lasting effects. | X | Testing included relationships with handlers, dominance, confidence-timidity rating, activity ratings, changes in heart rate and body weight. | X | Disturbances during development are most important during periods when new social relationships are being formed. Also detailed critical periods of dog development. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McEvoy, V.; Espinosa, U.B.; Crump, A.; Arnott, G. Canine Socialisation: A Narrative Systematic Review. Animals 2022, 12, 2895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12212895

McEvoy V, Espinosa UB, Crump A, Arnott G. Canine Socialisation: A Narrative Systematic Review. Animals. 2022; 12(21):2895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12212895

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcEvoy, Victoria, Uri Baqueiro Espinosa, Andrew Crump, and Gareth Arnott. 2022. "Canine Socialisation: A Narrative Systematic Review" Animals 12, no. 21: 2895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12212895

APA StyleMcEvoy, V., Espinosa, U. B., Crump, A., & Arnott, G. (2022). Canine Socialisation: A Narrative Systematic Review. Animals, 12(21), 2895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12212895