Pandemic Puppies: Demographic Characteristics, Health and Early Life Experiences of Puppies Acquired during the 2020 Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the UK

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Cleaning

2.4. Qualitative Content Analysis

2.5. Health Data Coding

2.6. Breed/Crossbreed Categorisation

2.7. Calculation of Typical Adult Bodyweight

2.8. Statistical Analysis

2.9. Spatial Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Owner Demographics

3.2. Puppy Demographics

3.2.1. Breed/Crossbreed Characteristics

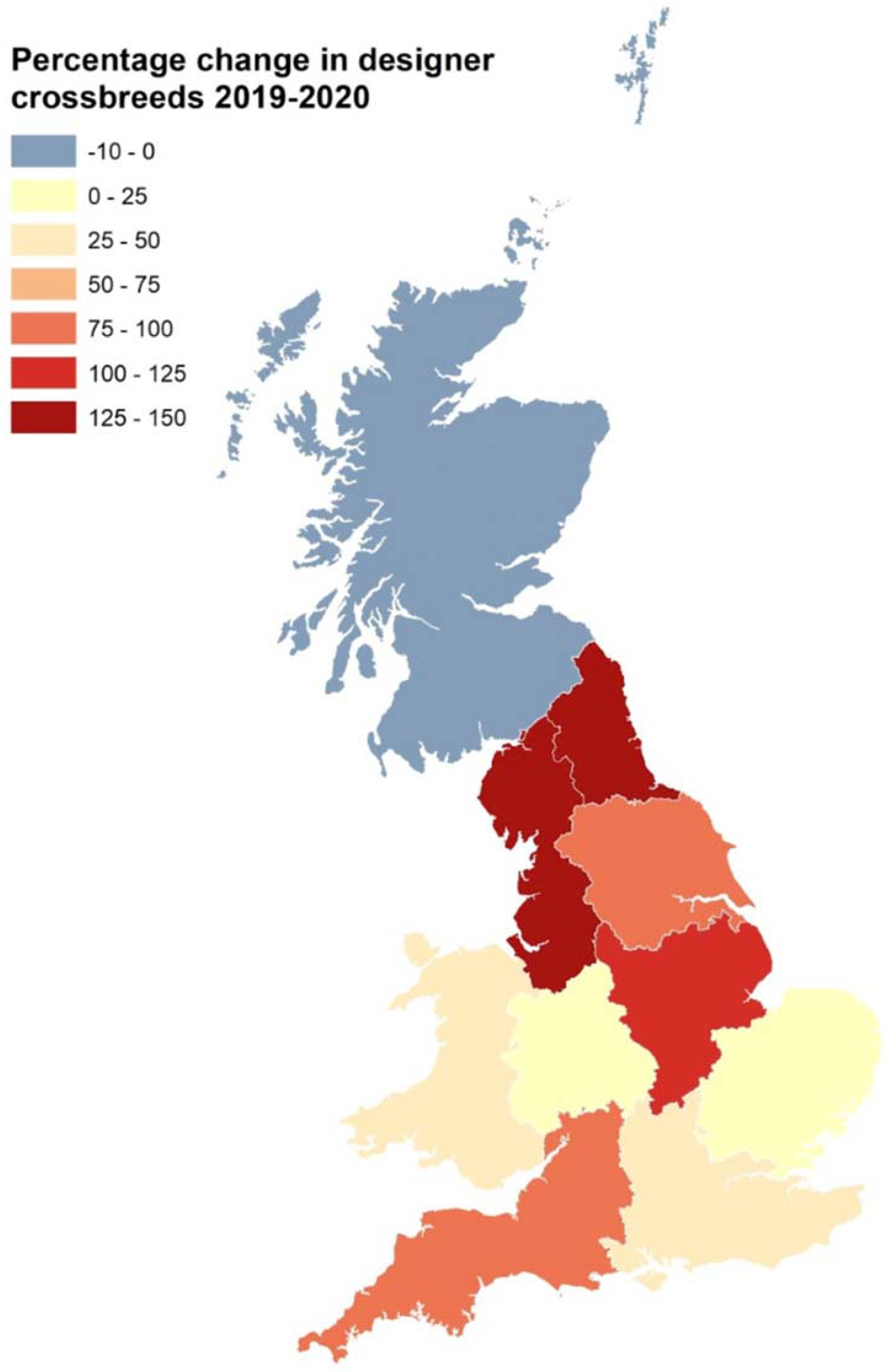

3.2.2. Spatial Analysis of Designer Crossbreeds in the Pandemic Puppy Cohort

3.3. Breeder Provisions

3.4. Puppy Health Soon after Acquisition

3.5. Puppy Socialisation Experiences and Behaviour Soon after Acquisition

3.5.1. Being Left Alone

3.5.2. Socialisation Experiences under 16 Weeks of Age

3.5.3. Attendance at Puppy Training Classes

3.5.4. Attendance at Puppy Training Classes: Multivariable Analysis

3.5.5. Puppy Behaviour

3.6. Puppy Relinquishment

4. Discussion

4.1. Socialisation and Habituation Practices

4.1.1. Puppy Classes

4.1.2. Owner-Led Socialisation Activities

4.2. Separation-Related Behaviours

4.3. Problem Behaviours

4.4. Preventative Healthcare and Early-Life Health

4.5. Early Provisions and Advice Offered by Breeders

4.6. Breed Demographics

4.7. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Packer, R.M.A.; Brand, C.L.; Belshaw, Z.; Pegram, C.L.; Stevens, K.B.; O’Neill, D.G. Pandemic Puppies: Characterising motivations and behaviours of UK owners who purchased puppies during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Animals 2021, 11, 2500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- The Kennel Club. The COVID-19 Puppy Boom—One in Four Admit Impulse Buying a Pandemic Puppy. Available online: https://www.theken-nelclub.org.uk/media-centre/2020/august/the-covid-19-puppy-boom-one-in-four-admit-impulse-buying-a-pandemic-puppy (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Mills, G. Puppy prices soar in COVID-19 lockdown. Vet. Record 2020, 187, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Dogs Trust. Dogs Trust Advises Public Against Being #Dogfished. Available online: https://www.dogstrust.org.uk/latest/2020/dogs-trust-advises-public-against-being-dogfished (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Siettou, C. Societal interest in puppies and the COVID-19 pandemic: A google trends analysis. Prev. Vet. Med. 2021, 196, 105496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogs Trust. Puppy Smuggling: Puppies Still Paying as Government Delays. Available online: https://www.dogstrust.org.uk/puppy-smuggling/041220_advert%20report_puppy%20smuggling%20a4_v15.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Scott, J.P. Critical periods in the development of social behavior in puppies. Psychosom. Med. 1958, 20, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Scott, J.P.; Fuller, J.L. The critical period. In Genetics and the Social Behavior of the Dog; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1974; pp. 117–150. [Google Scholar]

- Hargrave, C. Socialisation: Is it the “be all and end all” of creating resilience in companion animals? Vet. Nurse 2021, 12, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, E.; Mikkola, S.; Salonen, M.; Puurunen, J.; Sulkama, S.; Araujo, C.; Lohi, H. Active and social life is associated with lower non-social fearfulness in pet dogs. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13774. [Google Scholar]

- Puurunen, J.; Hakanen, E.; Salonen, M.K.; Mikkola, S.; Sulkama, S.; Araujo, C.; Lohi, H. Inadequate socialisation, inactivity, and urban living environment are associated with social fearfulness in pet dogs. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Appleby, D.L.; Bradshaw, J.W.; Casey, R.A. Relationship between aggressive and avoidance behaviour by dogs and their experience in the first six months of life. Vet. Record 2002, 15, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, J.W.S.; McPherson, J.A.; Casey, R.A.; Larter, L.S. Aetiology of separation-related behaviour in domestic dogs. Vet. Record 2002, 51, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, J.B.H.; Sandøe, P.; Neilsen, S.S. Owner-Related Reasons Matter more than Behavioural Problems—A Study of Why Owners Relinquished Dogs and Cats to a Danish Animal Shelter from 1996 to 2017. Animals 2020, 10, 1064. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, C.; Jarvis, S.; McGreevy, P.; Heath, S.; Church, D.; Brodbelt, D.; O’Neill, D. Mortality resulting from undesirable behaviours in dogs aged under three years attending primary-care veterinary practices in England. Anim. Welf. 2018, 27, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wilson, B.; Masters, S.; Van Rooy, D.; McGreevy, P.D. Mortality Resulting from Undesirable Behaviours in Dogs Aged Three Years and under Attending Primary-Care Veterinary Practices in Australia. Animals 2021, 11, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals. PDSA Animal Wellbeing (PAW) Report 2021. Available online: https://www.pdsa.org.uk/what-we-do/pdsa-animal-wellbeing-report/paw-report-2021 (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Owczarczak-Garstecka, S.C.; Graham, T.M.; Archer, D.C.; Westgarth, C. Dog walking before and during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: Experiences of UK dog owners. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoesmith, E.; Santos de Assis, L.; Shahab, L.; Ratschen, E.; Toner, P.; Kale, D.; Reeve, C.; Mills, D.S. The perceived impact of the first UK COVID-19 lockdown on companion animal welfare and behaviour: A mixed-method study of associations with owner mental health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, K.E.; Owczarczak-Garstecka, S.C.; Anderson, K.L.; Casey, R.A.; Christley, R.M.; Harris, L.; McMillan, K.M.; Mead, R.; Murray, J.K.; Samet, L. “More Attention than Usual”: A Thematic Analysis of Dog Ownership Experiences in the UK during the First COVID-19 Lockdown. Animals 2021, 11, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christley, R.M.; Murray, J.K.; Anderson, K.L.; Buckland, E.L.; Casey, R.A.; Harvey, N.D.; Harris, L.; Holland, K.E.; McMillan, K.M.; Mead, R. Impact of the First COVID-19 Lockdown on Management of Pet Dogs in the UK. Animals 2021, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, D.G.; Church, D.B.; McGreevy, P.D.; Thomson, P.C.; Brodbelt, D.C. Prevalence of disorders recorded in dogs attending primary-care veterinary practices in England. PLoS ONE. 2014, 9, e90501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- VetCompass™. VetCompass Programme. Available online: https://www.rvc.ac.uk/vetcompass (accessed on 7 February 2021).

- The Kennel Club. Breeds A to Z. Available online: https://www.thekennelclub.org.uk/search/breeds-a-to-z/ (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Fédération Cynologique Internationale. FCI Breeds Nomenclature. Available online: http://www.fci.be/en/Nomenclature/Default.aspx (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- American Kennel Club. Dog Breeds. Available online: https://www.akc.org/dog-breeds/ (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Edmunds, G.L.; Smalley, M.J.; Beck, S.; Errington, R.J.; Gould, S.; Winter, H.; Brodbelt, D.C.; O’Neill, D.G. Dog breeds and body conformations with predisposition to osteosarcoma in the UK: A case-control study. Canine Genet. Epidemiol. 2021, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, K.; Anderson, D.R. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics. National Statistics Postcode Lookup. Available online: https://geoportal.statistics.gov.uk/datasets/ons::national-sta-tistics-postcode-lookup-may-2021/about (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Office for National Statistics. Population Estimates for UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/datasets/mid-year-pop-est/editions/mid-2019-april-2020-geography/versions/2 (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- HM Government. Bringing Your Pet to Great Britain. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/bring-your-pet-to-great-britain (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- HM Government. Import Live Animals and Germinal Products to Great Britain under Balai Rules. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/import-live-animals-and-germinal-products-to-great-britain-under-balai-rules (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Woskie, L.R.; Hennessy, J.; Espinosa, V.; Tsai, T.C.; Vispute, S.; Jacobson, B.H.; Cattuto, C.; Gauvin, L.; Tizzoni, M.; Fabrikant, A.; et al. Early social distancing policies in Europe, changes in mobility and COVID-19 case trajectories: Insights from Spring 2020. PLoS ONE 2021, 169, e0253071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, L.; Arnold, A.K.; Goerlich-Jansson, C.C.; Vinke, C.M. The importance of early life experiences for the development of behavioural disorders in domestic dogs. Behaviour 2018, 155, 83–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González-Martínez, Á.; Martínez, M.F.; Rosado, B.; Luño, I.; Santamarina, G.; Suárez, M.L.; Camino, F.; de la Cruz, L.F.; Diéguez, F.J. Association between puppy classes and adulthood behavior of the dog. J. Vet. Behav. 2019, 32, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinwoodie, I.R.; Zottola, V.; Dodman, N.H. An Investigation into the Impact of Pre-Adolescent Training on Canine Behavior. Animals 2021, 11, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurachi, T.; Irimajiri, M. Preliminary study on the effects of attendance at dog training school on minimizing development of some anxiety disorders. J. Vet. Behav. 2019, 34, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, T.J.; King, T.; Bennett, P.C. Puppy parties and beyond: The role of early socialization practices on adult dog behavior. Vet. Med. Res. Rep. 2015, 6, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Casey, R.A.; Loftus, B.; Bolster, C.; Richards, G.J.; Blackwell, E.J. Human directed aggression in domestic dogs (Canis familiaris): Occurrence in different contexts and risk factors. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 152, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, M.M.; Jackson, J.A.; Line, S.W.; Anderson, R.K. Evaluation of association between retention in the home and attendance at puppy socialization classes. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2003, 223, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blackwell, E.J.; Bolster, C.; Richards, G.; Loftus, B.A.; Casey, R.A. The use of electronic collars for training domestic dogs: Estimated prevalence, reasons and risk factors for use, and owner perceived success as compared to other training methods. BMC Vet. Res. 2012, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woodward, J.L.; Casey, R.A.; Lord, M.S.; Kinsman, R.H.; Da Costa, R.E.P.; Knowles, T.G.; Tasker, S.; Murray, J.K. Factors influencing owner-reported approaches to training dogs enrolled in the Generation Pup longitudinal study. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 242, 105404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakeman, M.; Oxley, J.A.; Owczarczak-Garstecka, S.C.; Westgarth, C. Pet dog bites in children: Management and prevention. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2020, 4, e000726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, J.L.; Buckland, E.L.; Murray, J.K.; Da Costa, R.E.P.; Casey, R.A. Back to school: Exploring the reasons why adopters do not plan to take their recently adopted dog to training classes. In Proceedings of the Universities Federation for Animal Welfare Conference, Online, 29–30 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Arhant, C.; Bubna-Littitz, H.; Bartels, A.; Futschik, A.; Troxler, J. Behaviour of smaller and larger dogs: Effects of training methods, inconsistency of owner behaviour and level of engagement in activities with the dog. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2010, 123, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, M.S.; Casey, R.A.; Kinsman, R.H.; Tasker, S.; Knowles, T.G.; Da Costa, R.E.P.; Woodward, J.L.; Murray, J.K. Owner perception of problem behaviours in dogs aged 6 and 9-months. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2020, 232, 105147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.; Durston, T.; Flatman, J.; Kelly, D.; Moat, M.; Mohammed, R.; Smith, T.; Wickes, M.; Upjohn, M.; Casey, R. Impact of Socio-Economic Status on Accessibility of Dog Training Classes. Animals 2019, 9, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, J.; Kirk-Wade, E. Coronavirus: A History of English Lockdown Laws. Available online: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9068/ (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Ogata, N. Separation anxiety in dogs: What progress has been made in our understanding of the most common behavioural problems in dogs? J. Vet. Behav. 2016, 16, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, S. Guidance for Puppy Owners: Leaving the Puppy Alone. In Practical Canine Behaviour for Veterinary Nurses and Technicians, 2nd ed.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2021; pp. 170–172. [Google Scholar]

- Bescoby, R. Preventing Separation-Related Behaviours Developing in Puppies. 2020. Available online: https://www.veterinary-practice.com/article/preventing-separation-related-behaviours-developing-in-puppies (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Blackwell, E.J.; Casey, R.A.; Bradshaw, J.W.S. Efficacy of written behavioral advice for separation-related behavior problems in dogs newly adopted from a rehoming center. J. Vet. Behav. 2016, 12, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, J.; García, E.; Darder, P.; Argüelles, J.; Fatjó, J. The effects of the Spanish COVID-19 lockdown on people, their pets and the human-animal bond. J. Vet. Behav. 2020, 40, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Angelo, D.; Chirico, A.; Sacchettino, L.; Manunta, F.; Martucci, M.; Cestaro, A.; Avallone, L.; Giordano, A.; Ciani, F. Human-Dog Relationship during the First COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy. Animals 2021, 11, 2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogs Trust. The Impact of the COVID-19 Lockdown Restrictions on Dogs and Dog Owners in the UK. Available online: https://www.dogstrust.org.uk/help-advice/research/research-papers/201020_covid%20report_v8.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- Waite, M.R.; Harman, M.J.; Kodak, T. Frequency and animal demographics of mouthing behaviour in companion dogs in the United States. Learn. Motiv. 2021, 74, 101726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, K.; Ballantyne, K.C. Living with and loving a pet with behavioral problems: Pet owner’s experiences. J. Vet. Behav. 2020, 37, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Veterinary Association. Respect Your Vet Team during COVID-19, Says BVA. Available online: https://www.bva.co.uk/news-and-blog/news-article/respect-your-vet-team-during-covid-19-says-bva/ (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- O’Neill, D.G.; James, H.; Brodbelt, D.C.; Church, D.B.; Pegram, C. Prevalence of commonly diagnosed disorders in UK dogs under primary veterinary care: Results and applications. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owczarczak-Garstecka, S.; Holland, K.; Anderson, K.; Casey, R.; Christley, R.; Harris, L.; McMillan, K.; Mead, R.; Murray, J.; Samet, L.; et al. Concerns and Experiences of Accessing Veterinary Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed-methods Analysis of Dog Owners’ Responses. In Proceedings of the Canine Science Forum, Virtual Meeting, 6–9 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- HM Government. The Microchipping of Dogs (England) Regulations 2015. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2015/108/contents/made (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- HM Government. The Microchipping of Dogs (Scotland) Regulations 2016. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/sdsi/2016/9780111030233/contents (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- HM Government. The Microchipping of Dogs (Wales) Regulations 2015. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/wsi/2015/1990/made (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- HM Government. The Microchipping of Dogs (Northern Ireland) Regulations 2012. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/nisr/2012/132/contents (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- DEFRA. Petfished: Who’s the Person behind the Pet? Available online: https://getyourpetsafely.campaign.gov.uk (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- RSPCA. We’re Calling for a Law Change after Puppy Imports More than Double over Summer. Available online: https://www.rspca.org.uk/-/news-puppy-imports-more-than-double-during-summer (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Maher, J.; Wyatt, T. European illegal puppy trade and organised crime. Trends Organ. Crim. 2021, 24, 506–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Veterinary Association. Illegally Imported Pets? Guidance and Compliance Flowchart for Vets in Scotland. Available online: https://www.bva.co.uk/resources-support/practice-management/illegally-imported-pets-guidance-and-compliance-flowchart-for-vets-in-scotland/ (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Pet Insurance Australia. Available online: https://www.petinsuranceaustralia.com.au/covid-top-10-breeds/ (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Pets4Homes. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Pet Landscape. Available online: https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/e/2PACX-1vTlNzbjXcTaOXhd_wWJmZdASWHw6rGLxPyzTlBiAxrii0TzAHPXKzF02jWkdR5PgJxbUlDYztgJ_mHu/pub?start=false&loop=false&delayms=3000&slide=id.ga68ee19092_0_38 (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Vredegoor, D.W.; Willemse, T.; Chapman, M.D.; Heederik, D.J.; Krop, E.J. Can f 1 levels in hair and homes of different dog breeds: Lack of evidence to describe any dog breed as hypoallergenic. J. Allergy. Clin. Immunol. 2012, 130, 904–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Kennel Club. Breed Registration Statistics. Available online: https://www.thekennelclub.org.uk/media-centre/breed-registration-statistics/ (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Murray, J.K.; Kinsman, R.H.; Lord, M.S.; Da Costa, R.E.P.; Woodward, J.L.; Owczarczak-Garstecka, S.C.; Tasker, S.; Knowles, T.G.; Casey, R.A. ‘Generation Pup’—protocol for a longitudinal study of dog behaviour and health. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer, R.M.A.; Murphy, D.; Farnworth, M.J. Purchasing popular purebreds: Investigating the influence of breed-type on the pre-purchase attitudes and behaviour of dog owners. Anim. Welf. 2017, 26, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tulloch, J.S.P.; Minford, S.; Pimblett, V.; Rotheram, M.; Christley, R.M.; Westgarth, C. Paediatric emergency department dog bite attendance during the COVID-19 pandemic: An audit at a tertiary children’s hospital. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2021, 5, e001040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, C.A.; Mistry, R.D. Dog Bites in Children Surge during Coronavirus Disease-2019: A Case for Enhanced Prevention. J. Pediatrics 2020, 225, 231–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parente, G.; Gargano, T.; Di Mitri, M.; Cravano, S.; Thomas, E.; Vastano, M.; Maffi, M.; Libri, M.; Lima, M. Consequences of COVID-19 Lockdown on Children and Their Pets: Dangerous Increase of Dog Bites among the Paediatric Population. Children 2021, 8, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Breed/Crossbreed | 2019 | 2020 | Statistics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | Rank | n | % | Rank | % Change 2019 to 2020 | X2 | p Value | |

| Labrador Retriever | 134 | 11.7 | 1 | 429 | 9.9 | 1 | −15.4 | 3.34 | 0.067 |

| Cocker Spaniel | 81 | 7.1 | 2 | 324 | 7.4 | 3 | +4.2 | 0.19 | 0.667 |

| Cockapoo | 72 | 6.3 | 3 | 362 | 8.3 | 2 | +31.7 | 5.15 | 0.023 |

| Miniature Smooth-Haired Dachshund | 64 | 5.6 | 4 | 188 | 4.4 | 4 | −21.4 | 3.33 | 0.068 |

| Border Collie | 58 | 5.1 | 5 | 150 | 3.4 | 5 | −33.3 | 6.51 | 0.011 |

| Golden Retriever | 52 | 4.6 | 6 | 120 | 2.8 | 9 | −39.1 | 9.51 | 0.002 |

| Border Terrier | 42 | 3.7 | 7 | 140 | 3.2 | 7 | −13.5 | 0.57 | 0.449 |

| Crossbreed | 29 | 2.5 | 8 | 149 | 3.5 | 6 | +40.0 | 2.30 | 0.129 |

| German Shepherd Dog | 27 | 2.4 | 9 | 86 | 2.0 | 12 | −16.7 | 0.65 | 0.419 |

| English Springer Spaniel | 24 | 2.1 | 10 | 96 | 2.2 | 11 | +4.8 | 0.02 | 0.820 |

| Labradoodle | 23 | 2.0 | 11 | 127 | 2.9 | 8 | +45.0 | 2.83 | 0.092 |

| Cavapoo | 20 | 1.7 | 12 | 111 | 2.6 | 10 | +52.9 | 2.52 | 0.112 |

| Timepoint | Breeder Provision | Acquisition Year | Statistics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019% | 2020% | X2 | p Value | ||

| Prior to bringing puppy home (Total n = 5168; 2019 n = 1063, 2020 n = 4035) | Microchip | 92.4 | 93.2 | 0.84 | 0.360 |

| Worming treatment | 89.8 | 89.6 | 0.05 | 0.831 | |

| Health check by a veterinary surgeon | 91.3 | 87.4 | 12.07 | <0.001 | |

| Flea treatment | 69.3 | 68.6 | 0.18 | 0.669 | |

| First vaccinations | 67.0 | 67.4 | 0.06 | 0.802 | |

| Second vaccinations | 8.4 | 6.4 | 5.05 | 0.025 | |

| When puppy was collected (Total n = 4368; 2019 n = 900, 2020 n = 3468) | Puppy’s microchip details | 92.7 | 92.1 | 0.62 | 0.891 |

| Puppy’s vaccinations record | 69.0 | 68.8 | 6.48 | 0.090 | |

| Feeding guidance in writing | 68.8 | 61.9 | 32.91 | <0.001 | |

| Copy of puppy’s pedigree | 61.7 | 47.3 | 70.10 | <0.001 | |

| Kennel Club change of ownership form | 59.4 | 43.6 | 76.90 | <0.001 | |

| Puppy’s passport * | 4.1 | 7.1 | 45.51 | <0.001 | |

| At any point in time (n = 4462; 2019 = 921, 2020 = 3541) | Advice on diet | 61.6 | 76.9 | 88.76 | <0.001 |

| Advice on your puppy’s health | 49.2 | 58.0 | 23.25 | <0.001 | |

| Advice on training/behaviour | 42.1 | 50.8 | 17.24 | <0.001 | |

| The option to return puppy to them in the future for any reason | 50.1 | 47.3 | 2.22 | 0.136 | |

| Advice on exercise regime | 32.5 | 37.8 | 8.91 | 0.003 | |

| None of the above | 21.5 | 14.4 | 27.57 | <0.001 | |

| The option to board puppy with them when on holiday | 17.0 | 12.0 | 16.19 | <0.001 | |

| Puppies Sold with a Pet Passport (n = 4314) | Acquisition Year | |

|---|---|---|

| 2019% (n = 884) | 2020% (n = 3430) | |

| 13 to 16 weeks old | 27.8 | 12.6 |

| 11 to 12 weeks old | 2.8 | 5.7 |

| 9 to 10 weeks old | 33.3 | 25.2 |

| 7 to 8 weeks old | 36.1 | 56.5 |

| Under 6 weeks old | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| I’m not sure/I can’t remember | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Soon after You Brought Your Puppy Home, Did You Notice Any of the Following? (n = 5571) | Acquisition Year | Statistics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019% (n = 1148) | 2020% (n = 4369) | X2 | p Value | |

| Enteropathy * | 10.2 | 9.9 | 0.09 | 0.760 |

| Parasite infestation * | 2.1 | 4.7 | 5.27 | 0.022 |

| Skin (cutaneous) disorder * | 2.2 | 4.3 | 10.88 | <0.001 |

| Ophthalmological disorder * | 2.6 | 2.4 | 0.21 | 0.648 |

| Upper respiratory tract disorder * | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.59 | 0.444 |

| Ear (aural) disorder | 0.4 | 0.2 | 1.89 | 0.169 |

| Undesirable behaviour disorder | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.13 | 0.720 |

| Thin/underweight | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.57 | 0.450 |

| Traumatic injury | 0.3 | 0.1 | 3.11 | 0.078 |

| Musculoskeletal disorder | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.32 | 0.251 |

| Polyuria/Polydipsia | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.836 |

| Anal sac disorder | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.53 | 0.468 |

| Haematopoietic system disorder | 0.1 | 0.0 | 3.81 | 0.051 |

| Oral cavity (mouth) disorder | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.26 | 0.608 |

| Vascular disorder | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.26 | 0.608 |

| Female reproductive abnormality | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.29 | 0.593 |

| Lower respiratory tract disorder | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.26 | 0.608 |

| Hearing impaired/deafness | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.26 | 0.608 |

| Heart (cardiac) disease | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.53 | 0.468 |

| Collapsed | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.26 | 0.608 |

| Hernia | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.53 | 0.468 |

| Lethargy | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.53 | 0.468 |

| Mass/lump/swelling | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.26 | 0.608 |

| Appetite disorder | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.04 | 0.309 |

| Tail disorder | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.26 | 0.608 |

| Urinary system disorder | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.29 | 0.593 |

| Drug therapy adverse reaction | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.63 | 0.468 |

| Abdominal disorder | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.26 | 0.608 |

| Foreign body | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.26 | 0.608 |

| Complication associated with clinical care procedure | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.26 | 0.608 |

| Is Your Puppy/Dog Insured? (n = 5439) | Acquisition Year | |

|---|---|---|

| 2019% (n = 1140) | 2020% (n = 4352) | |

| Yes | 83.5 | 84.0 |

| No, and I do not plan to insure them | 10.7 | 7.3 |

| No, but I plan to insure them in the future | 3.2 | 7.0 |

| No, they were insured but I have since cancelled or did not renew their policy | 2.5 | 1.7 |

| No, I have never heard of pet insurance | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Has Your Puppy/Dog Been Vaccinated, or Do You Plan to in the Future? (n = 5172) | Acquisition Year | |

|---|---|---|

| 2019% (n = 1073) | 2020% (n = 4099) | |

| Yes—first and second vaccinations | 92.7 | 82.5 |

| Yes—just their first vaccinations | 6.8 | 15.2 |

| No—not yet, but I plan to in the future | 0.2 | 1.9 |

| No—I have chosen not to vaccinate my puppy/dog and don’t plan to in the future | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| No—not yet, I haven’t decided | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Has Your Puppy/Dog Been Neutered, or Do you Plan to Have Them Neutered in the Future? (n = 5098) | Acquisition Year | |

|---|---|---|

| 2019% (n = 1053) | 2020% (n = 4072) | |

| No, but I intend to have them neutered when they are older | 21.4 | 45.4 |

| No, not yet, I haven’t decided | 14.2 | 21.7 |

| No, but I do not plan to breed from them | 11.2 | 7.2 |

| No, because I plan to breed from them | 10.3 | 6.1 |

| Yes, aged under 6 months | 3.6 | 2.9 |

| Yes, aged over 6 months | 39.4 | 16.6 |

| Whilst Your Puppy Was Under 16 Weeks of Age, Did You Deliberately Leave Them Alone for Any Period of Time to Get Them Used to Being Left Alone? (n = 5101) | Acquisition Year | |

|---|---|---|

| 2019% (n = 1052) | 2020% (n = 4049) | |

| Yes | 81.0 | 74.6 |

| No | 16.6 | 15.9 |

| No, not as yet but I plan to before my puppy is 16 weeks old (if applicable) | 0.1 | 9.0 |

| I can’t remember | 2.3 | 0.5 |

| Experience (Total; 2019, 2020) | Response | Acquisition Year | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019% | 2020% | |||

| Travelling in a car (total n = 4461; 2019 n = 921, 2020 = 3540) | Yes | 98.9 | 98.6 | X2 = 5.80 p < 0.122 |

| No | 1.1 | 0.8 | ||

| I’m not sure/can’t remember | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| No, not as yet but I plan to before my puppy is 16 weeks old (if applicable) | 0.0 | 0.5 | ||

| Meet any people from outside your household (total n = 4466; 2019 n = 922, 2020 n = 3544) | Yes | 93.8 | 90.5 | X2= 35.89 p< 0.001 |

| No | 4.8 | 5.6 | ||

| I’m not sure/can’t remember | 1.4 | 0.7 | ||

| No, not as yet but I plan to before my puppy is 16 weeks old (if applicable) | 0.0 | 3.2 | ||

| Visitors to their home (total n = 4449; 2019 n = 920, 2020 n = 3529) | Yes | 94.5 | 81.8 | X2= 103.05 p< 0.001 |

| No | 4.6 | 12.8 | ||

| I’m not sure/can’t remember | 1.0 | 0.7 | ||

| No, not as yet but I plan to before my puppy is 16 weeks old (if applicable) | 0.0 | 4.8 | ||

| Walking in a public space (i.e., outside of your home/ garden) (total n = 4459; 2019 n = 921, 2020 n = 3538) | Yes | 87.5 | 78.3 | X2= 151.27 p< 0.001 |

| No | 10.7 | 9.4 | ||

| I’m not sure/can’t remember | 1.7 | 0.2 | ||

| No, not as yet but I plan to before my puppy is 16 weeks old (if applicable) | 0.0 | 12.1 | ||

| Walking near traffic (total n = 4438; 2019 n = 918, 2020 n = 3520) | Yes | 85.0 | 78.0 | X2= 131.16 p< 0.001 |

| No | 13.1 | 10.9 | ||

| I’m not sure/can’t remember | 2.0 | 0.4 | ||

| No, not as yet but I plan to before my puppy is 16 weeks old (if applicable) | 0.0 | 10.8 | ||

| Meet any dogs from outside your household (total n = 4466; 2019 n = 922, 2020 n = 3544) | Yes | 80.4 | 76.3 | X2= 86.28 p< 0.001 |

| No | 18.0 | 14.8 | ||

| I’m not sure/can’t remember | 1.6 | 0.8 | ||

| No, not as yet but I plan to before my puppy is 16 weeks old (if applicable) | 0.0 | 8.1 | ||

| Fireworks (total n = 4394; 2019 n = 904, 2020 n = 3490) | Yes | 31.7 | 44.4 | X2= 132.01 p< 0.001 |

| No | 61.3 | 50.8 | ||

| I’m not sure/can’t remember | 7.0 | 1.9 | ||

| No, not as yet but I plan to before my puppy is 16 weeks old (if applicable) | 0.0 | 2.9 | ||

| Thunderstorms (total n = 4362; 2019 n = 900, 2020 n = 3462) | Yes | 28.0 | 30.9 | X2= 294.31 p< 0.001 |

| No | 43.6 | 55.9 | ||

| I’m not sure/can’t remember | 28.4 | 8.4 | ||

| No, not as yet but I plan to before my puppy is 16 weeks old (if applicable) | 0.0 | 4.8 | ||

| Dog groomer (total n = 4376; 2019 n = 898, 2020 n = 3478) | Yes | 19.9 | 20.2 | X2= 99.31 p< 0.001 |

| No | 78.3 | 70.8 | ||

| I’m not sure/can’t remember | 1.8 | 0.4 | ||

| No, not as yet but I plan to before my puppy is 16 weeks old (if applicable) | 0.0 | 8.5 | ||

| Did You or Someone in Your Household Attend Any Puppy Classes with Your Puppy before They Were 16 Weeks Old? (n = 5100) | Acquisition Year | |

|---|---|---|

| 2019% (n = 1053) | 2020% (n = 4047) | |

| Yes, in-person puppy classes | 67.9 | 28.9 |

| No, I wanted to but there weren’t any classes running | 8.3 | 28.9 |

| No, I do not intend to | 19.6 | 17.7 |

| No, not as yet but I plan to before my puppy is 16 weeks old (if applicable) | 0.0 | 16.6 |

| Yes, online puppy classes | 1.0 | 6.7 |

| * No, I chose not to because I am a dog professional | 1.3 | 0.9 |

| * No, I was unable to attend < 16 weeks due to my puppy’s circumstances (e.g., poor health, acquired close to 16 weeks) | 1.3 | 0.3 |

| * No, my puppy died aged <16 weeks | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| * No, I was unable to attend classes while my puppy was <16 weeks due to my own circumstances (e.g., health, work commitments) | 0.7 | 0.0 |

| Variable | Category | Odds Ratio | 95% CI * | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Year of acquisition | 2019 | Reference | ||

| 2020 | 0.23 | 0.20 to 0.27 | <0.001 | ||

| Dog demographics | Breed designation | Crossbred | Reference | ||

| Purebred | 1.39 | 0.97 to 1.98 | 0.074 | ||

| Designer Crossbred | 1.35 | 0.94 to 1.96 | 0.109 | ||

| Typical adult bodyweight | ≤10 kg | 0.65 | 0.55 to 0.76 | <0.001 | |

| 10 to <20 kg | Reference | ||||

| 20 to <30 kg | 1.07 | 0.91 to 1.26 | 0.430 | ||

| 30 to <40 kg | 1.06 | 0.88 to 1.28 | 0.557 | ||

| ≥40 kg | 1.26 | 0.85 to 1.87 | 0.255 | ||

| Dog sex | Male | Reference | |||

| Female | 0.99 | 0.88 to 1.12 | 0.867 | ||

| Neutered | No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.12 | 0.97 to 1.29 | 0.120 | ||

| Owner demographics | Owner age | 18 to 24 years old | 0.61 | 0.46 to 0.81 | <0.001 |

| 25 to 34 years old | Reference | ||||

| 35 to 44 years old | 1.23 | 1.01 to 1.50 | 0.037 | ||

| 45 to 54 years old | 1.21 | 1.01 to 1.46 | 0.045 | ||

| 55 to 64 years old | 1.04 | 0.85 to 1.28 | 0.709 | ||

| 65 to 74 years old | 0.87 | 0.66 to 1.15 | 0.334 | ||

| 75 years or older | 1.30 | 0.67 to 2.49 | 0.436 | ||

| Owner gender | Female | Reference | |||

| Male | 0.75 | 0.60 to 0.92 | 0.007 | ||

| Other | 0.78 | 0.23 to 2.60 | 0.685 | ||

| Live with children | No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.86 | 0.74 to 0.99 | 0.042 | ||

| Region | Scotland | Reference | |||

| Northern Ireland | 0.32 | 0.13 to 0.77 | 0.011 | ||

| Wales | 0.96 | 0.66 to 1.41 | 0.840 | ||

| East of England | 2.12 | 1.63 to 2.75 | <0.001 | ||

| East Midlands | 1.37 | 0.99 to 1.88 | 0.055 | ||

| London | 1.59 | 1.19 to 2.11 | 0.001 | ||

| North East | 1.34 | 0.93 to 1.94 | 0.121 | ||

| North West | 1.19 | 0.88 to 1.63 | 0.261 | ||

| South East | 1.74 | 1.35 to 2.25 | <0.001 | ||

| South West | 1.67 | 1.26 to 2.20 | <0.001 | ||

| West Midlands | 1.42 | 1.04 to 1.93 | 0.028 | ||

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 1.22 | 0.90 to 1.66 | 0.202 | ||

| Dog owning experience | Previously owned a dog | No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.59 | 0.51 to 0.68 | <0.001 |

| Does Your Puppy/Dog Currently Show Any of the Following Behaviours that You/Your Household Find Problematic? (n = 4426) | Acquisition Year | |

|---|---|---|

| 2019% (n = 915) | 2020% (n = 3511) | |

| Jumping up at people | 30.3 | 36.1 |

| Mouthing | 9.7 | 33.1 |

| Pulling on their lead | 38.6 | 31.0 |

| Clinginess (e.g., following you, sitting close) | 19.8 | 23.7 |

| Not coming back when called | 21.7 | 16.3 |

| Barking or howling when left alone | 10.9 | 15.8 |

| Chasing, e.g., cats, wildlife | 24.9 | 10.6 |

| Toileting (weeing or pooing) in the house when left alone | 4.4 | 9.1 |

| Barking at other dogs | 16.9 | 8.1 |

| Anxiety/fear around unfamiliar people | 10.1 | 6.3 |

| Fear of loud sounds (e.g., fireworks, thunderstorms) | 8.3 | 4.9 |

| Anxiety/fear around other dogs | 6.8 | 4.3 |

| Being destructive when left alone | 5.2 | 4.3 |

| Guarding of food, toys, or other items | 4.9 | 2.8 |

| Aggression towards people in your household (including you) | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Aggression towards unfamiliar people | 2.5 | 0.6 |

| Aggression towards other dogs | 3.5 | 0.5 |

| Anxiety/fear around people in your household (including you) | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Not applicable – I no longer have my puppy | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| None of the above | 23.0 | 22.9 |

| Have You Considered, or Have You Needed to, Rehome Your Puppy/Dog Since You Acquired Them? (n = 5094) | Acquisition Year | |

|---|---|---|

| 2019% (n = 1050) | 2020% (n = 4044) | |

| I still have my puppy/dog and have not considered rehoming them | 98.6 | 98.3 |

| I still have my puppy/dog, but I have considered, or I am currently considering rehoming them | 0.9 | 1.2 |

| Not applicable—my puppy/dog has passed away | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Not applicable—my puppy/dog was put to sleep | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| I have rehomed my puppy/dog to another person/family | 0.2 | 0.0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brand, C.L.; O’Neill, D.G.; Belshaw, Z.; Pegram, C.L.; Stevens, K.B.; Packer, R.M.A. Pandemic Puppies: Demographic Characteristics, Health and Early Life Experiences of Puppies Acquired during the 2020 Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the UK. Animals 2022, 12, 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12050629

Brand CL, O’Neill DG, Belshaw Z, Pegram CL, Stevens KB, Packer RMA. Pandemic Puppies: Demographic Characteristics, Health and Early Life Experiences of Puppies Acquired during the 2020 Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the UK. Animals. 2022; 12(5):629. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12050629

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrand, Claire L., Dan G. O’Neill, Zoe Belshaw, Camilla L. Pegram, Kim B. Stevens, and Rowena M. A. Packer. 2022. "Pandemic Puppies: Demographic Characteristics, Health and Early Life Experiences of Puppies Acquired during the 2020 Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the UK" Animals 12, no. 5: 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12050629

APA StyleBrand, C. L., O’Neill, D. G., Belshaw, Z., Pegram, C. L., Stevens, K. B., & Packer, R. M. A. (2022). Pandemic Puppies: Demographic Characteristics, Health and Early Life Experiences of Puppies Acquired during the 2020 Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the UK. Animals, 12(5), 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12050629