Understanding Circadian and Circannual Behavioral Cycles of Captive Giant Pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) Can Help to Promote Good Welfare

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Study Animal Selection

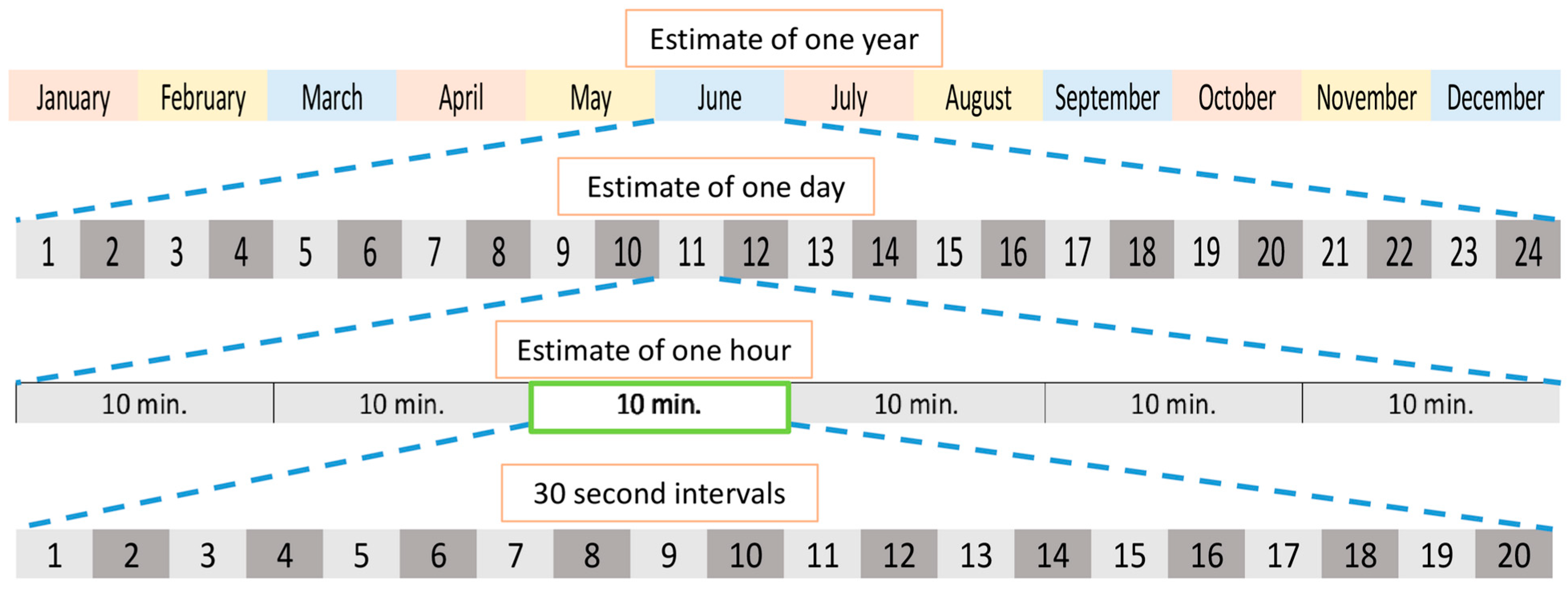

2.3. Behavior Observations

2.4. Analyses

2.4.1. Variables

2.4.2. Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial Modeling and Post hoc Pairwise Comparisons

2.4.3. Continuous Wavelet Transform and Wavelet Coherence Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Activity

3.2. Stereotypical/Abnormal Behaviors

3.3. Sexual-Related Behaviors

3.4. Mother and Cub Behaviors

4. Discussion

4.1. Holistic View of Active and Inactive Behavior Provides Insight into Energy and Behavioral Dynamics

4.2. Relationships between Migratory, Sexual-Related, Feeding, and Stereotypical/Abnormal Behavioral Cycles

4.3. Case Study of Mother and Cub

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Behavior | Welfare Valence | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solitary | |||

| Resting/ sleeping | Neutral | Inactivity (lying, sitting, or standing on all fours), either awake or asleep. If standing, the panda should not be investigating or seem as though its attention is on anything specific. Shifting between resting positions still counts as resting as long as it does not involve locomotion or becoming alert. | [92] |

| Locomotion | Neutral | Directional travel at any speed. Only includes short bouts of travel with a seemingly intended goal, or long bouts of travel with no evidence of a stereotypical or repetitive pattern. Includes climbing. | |

| Feeding/ foraging | Positive | The manipulation or consumption of food/water provided by keepers or foraging for plants growing in enclosure. Includes food search activity, moving around enclosure, and sniffing ground or air. | |

| Playing | Positive | Playful running, gymnastics, or interacting with objects (paw or mouth manipulation of objects—includes enrichment items). Includes playing in water (for example, splashing). | |

| Investigating | Positive | Panda places its nose within 5 cm of inedible object and sniffs or licks the object. | [93] |

| Anogenital rubbing (sexual-related) | Positive | Applying pressure to the hind area below the tail by moving the hind quarters in a back-and-forth motion around or up and down on the surface of an object or on the wall. Can be performed in one of the following four positions: squat, reverse (backing up to a vertical surface), leg cock (against a vertical surface with one leg raised), or a full handstand (both hindfeet elevated off the ground with body fully extended). | [63,94] |

| Scent anointing (sexual-related) | Positive | Rubbing face, head, neck, and/or shoulders on object or wall in fluid movements or by rolling on it, making contact with head, neck, shoulders, and upper back. Can use paws to try and spread odor. | [61,62] |

| Urinating/ defecating | Neutral | Assuming a squat, leg cock, handstand, or standing posture on the wall or ground to excrete urine or feces. | [94] |

| Grooming | Positive | Scratching and licking of the pelage. | |

| Drinking | Neutral | Placing mouth at surface of pools or spouts and ingesting water. | |

| Keeper interaction | Can be either positive or negative | Training or any interaction where the keeper is intentionally trying to gain and maintain the attention of the panda. Can occur at any location in the enclosure where the keeper is visible to the panda. | |

| Social | |||

| Aggressive | Negative | Animal forcefully swats with forepaws, lunges towards another individual, grapples, or bites with force. | [95] |

| Showing interest (sexual-related) | Positive | Animal responds to the other party by sniffing the other participant, pushing or pulling at the fence between them, or swaying or locomoting back and forth with proximity to the other animal which must be clearly in view, even if through a mesh barrier. | |

| Sexual (sexual-related) | Positive | Female presents anogenital region to male. Male sniffs or licks anogenital region and/or nudges or paws at anogenital region through wire mesh. Note that the female must first display “sexual” behavior before the male responds with “sexual” behavior. | |

| Social playing | Positive | Nonaggressive chasing, wrestling, inhibited biting, or pawing at another individual. There should not be attempts to escape, and individuals can alternate between subordinate and dominant positions. | |

| Stereotypical/abnormal | |||

| Pacing | Negative | Stereotypical pacing (back and forth, or perimeter locomotion, in a repetitive sustained pattern, tracing the same route at least 3 times consecutively) or quasi-stereotypical pacing (same as stereotypical pacing, except animal travels in an irregular pattern 3 or more times in a row. Any pacing in which a predictable pattern emerges. There may be variations in the routine, or the animal may alternate between a limited number of travel paths). | Panda project PDX Wildlife * |

| Bipedal standing | Negative | Standing on hind legs and looking through glass, fence, or outside enclosure, seemingly in anticipation of something. | [96] |

| Self-mutilation | Negative | Self-inflicted physical harm, such as biting or chewing the tail or leg, or hitting the head against a wall. | |

| Cage climbing | Negative | Stands bipedally and sways, or makes climbing motions, as if attempting to escape. | [97] |

| Regurgitation | Negative | Vomits and re-ingests vomit repeatedly. | |

| Pirouetting | Negative | Stands on hind legs and spins body at least 90 degrees. | |

| Head tossing | Negative | Swings upward or to the side in a swinging movement. | |

| Maternal | |||

| Nursing | Positive | Mother is alert or relaxed, while cub suckles the mother’s nipples. This behavior takes precedence over all other behaviors (e.g., licking cub’s anogenital area). | [98] |

| Grooming cub | Positive | Mother licks any part of the cub’s body, other than the anogenital area, and/or bites the cub lightly and repetitively, using incisors, anywhere on its body. | |

| Licking cub’s anogenital area | Positive | Mother licks the cub’s anogenital area. | |

| Holding cub | Positive | Mother uses any part of her body (paw, mouth, foreleg) to hold/support the cub on her body. At least 50% of the cub’s body must be supported on some part of the mother’s body. | |

| Other maternal | Positive | Mother performs any other behavior involving the cub that is not described above (e.g., olfactory investigation of cub, repositioning cub). | |

References

- Froy, O. Circadian Rhythms, Aging, and Life Span in Mammals. Physiology 2011, 26, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siegel, J.M. Do all animals sleep? Trends Neurosci. 2008, 31, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, L.M.; de Alba, G.; Santos, S.; Szewczyk, T.M.; Mackenzie, S.A.; Sánchez-Vázquez, F.J.; Planellas, S.R. Circadian rhythm of preferred temperature in fish: Behavioural thermoregulation linked to daily photocycles in zebrafish and Nile tilapia. J. Therm. Biol. 2023, 113, 103544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuerlein, A.; Gwinner, E. Is food availability a circannual zeitgeber in tropical birds? A field experiment on stonechats in tropical Africa. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2002, 17, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brando, S.; Buchanan-Smith, H.M. The 24/7 approach to promoting optimal welfare for captive wild animals. Behav. Process. 2018, 156, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCain, S.; Ramsay, E.; Kirk, C. The effects of hibernation and captivity on glucose metabolism and thyroid hormones in American black bear (Ursus americanus). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2013, 44, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellor, D.J.; Beausoleil, N.J.; Littlewood, K.E.; McLean, A.N.; McGreevy, P.D.; Jones, B.; Wilkins, C. The 2020 Five Domains Model: Including human–animal interactions in assessments of animal welfare. Animals 2020, 10, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, H.E.; Robart, A.R.; Chopra, J.K.; Asinas, C.E.; Hahn, T.P.; Ramenofsky, M. Seasonal expression of migratory behavior in a facultative migrant, the pine siskin. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2016, 71, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zera, A.J.; Harshman, L.G. The Physiology of life history trade-offs in animals. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2001, 32, 95–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dudde, A.; Schrader, L.; Weigend, S.; Matthews, L.R.; Krause, E.T. More eggs but less social and more fearful? Differences in behavioral traits in relation to the phylogenetic background and productivity level in laying hens. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 209, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.A.; Berzins, I.K.; Fogarty, F.; Hamlin, H.J.; Guillette, L.J. Sound, stress, and seahorses: The consequences of a noisy environment to animal health. Aquaculture 2011, 311, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segner, H.; Sundh, H.; Buchmann, K.; Douxfils, J.; Sundell, K.S.; Mathieu, C.; Ruane, N.; Jutfelt, F.; Toften, H.; Vaughan, L. Health of farmed fish: Its relation to fish welfare and its utility as welfare indicator. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 38, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schoener, T.W. Theory of feeding strategies. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1971, 2, 369–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manoogian, E.N.; Panda, S. Circadian rhythms, time-restricted feeding, and healthy aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2016, 39, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzibasi-Tozzini, E.; Martinez-Nicolas, A.; Lucas-Sánchez, A. The clock is ticking. Ageing of the circadian system: From physiology to cell cycle. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 70, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyke, G.H.; Pulliam, H.R.; Charnov, E.L. Optimal foraging: A selective review of theory and tests. Q. Rev. Biol. 1977, 52, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Altman, J.D.; Gross, K.L.; Lowry, S.R. Nutritional and behavioral effects of gorge and fast feeding in captive lions. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2005, 8, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orban, D.A.; Siegford, J.M.; Snider, R.J. Effects of guest feeding programs on captive giraffe behavior. Zoo Biol. 2016, 35, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, B.T.S.; Araujo, J.F. Food entrainment: Major and recent findings. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salgado-Delgado, R.; Nadia, S.; Angeles-Castellanos, M.; Buijs, R.M.; Escobar, C. In a rat model of night work, activity during the normal resting phase produces desynchrony in the hypothalamus. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2010, 25, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschos, G.K. Circadian clocks, feeding time, and metabolic homeostasis. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- West, A.C.; Bechtold, D.A. The cost of circadian desynchrony: Evidence, insights and open questions. Bioessays 2015, 37, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depner, C.M.; Stothard, E.R.; Wright, K.P., Jr. Metabolic consequences of sleep and circadian disorders. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2014, 14, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Chang, H.-C. Physiological links of circadian clock and biological clock of aging. Protein Cell 2017, 8, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cincotta, A.H.; Schiller, B.C.; Landry, R.J.; Herbert, S.J.; Miers, W.R.; Meier, A.H. Circadian neuroendocrine role in age-related changes in body fat stores and insulin sensitivity of the male Sprague-Dawley rat. Chronobiol. Int. 1993, 10, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gamble, K.L.; Resuehr, D.; Johnson, C.H.S. Work and circadian dysregulation of reproduction. Front. Endocrinol. 2013, 4, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goldman, B.D. The circadian timing system and reproduction in mammals. Steroids 1999, 64, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, M.J.; Kennaway, D.J. Circadian rhythms and reproduction. Reproduction 2006, 132, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Favre, R.N.; Bonaura, M.; Tittarelli, C.; de la Sota, R.L.; Stornelli, M. Effect of refractoriness to long photoperiod on sperm production and quality in tomcats. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2012, 47, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turek, F.W. Circadian involvement in termination of the refractory period in two sparrows. Science 1972, 178, 1112–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.R. Sleep, sleeping sites, and sleep-related activities: Awakening to their significance. Am. J. Primatol. 1998, 46, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, S.Z.; Diaz-Abad, M.; Wickwire, E.M.; Scharf, S.M. The functions of sleep. AIMS Neurosci. 2015, 2, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigarev, I.N.; Pigareva, M.L. The state of sleep and the current brain paradigm. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fureix, C.; Meagher, R.K. What can inactivity (in its various forms) reveal about affective states in non-human animals? A review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 171, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harding, C.D.; Yovel, Y.; Peirson, S.N.; Hackett, T.D.; Vyazovskiy, V.V. Re-examining extreme sleep duration in bats: Implications for sleep phylogeny, ecology, and function. Sleep 2022, 45, zsac064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwinner Circadian and circannual programmes in avian migration. J. Exp. Biol. 1996, 199, 39–48. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, J.A.; Stouffer, P.C. Diet and preparation for spring migration in captive hermit thrushes (Catharus guttatus). Ornithology 2003, 120, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.C.; Donham, R.S.; Farner, D.S. Physiological preparation for Autumnal migration in white-crowned sparrows. Condor 1982, 84, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gwinner, E.; Czeschlik, D. On the significance of Spring migratory restlessness in caged birds. Oikos 1978, 30, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudo, R.; Tsukamoto, K. Migratory restlessness and the role of androgen for increasing behavioral drive in the spawning migration of the Japanese eel. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, X.; Skidmore, A.K.; Wang, T.; Yong, Y.; Prins, H.H.T. Giant panda movements in Foping Nature Reserve, China. J. Wildl. Manag. 2002, 66, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Skidmore, A.K.; Zeng, Z.; Beck, P.S.; Si, Y.; Song, Y.; Liu, X.; Prins, H.H. Migration patterns of two endangered sympatric species from a remote sensing perspective. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2010, 76, 1343–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hull, V.; Huang, J.; Zhou, S.; Xu, W.; Yang, H.; McConnell, W.J.; Li, R.; Liu, D.; Huang, Y.; et al. Activity patterns of the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca). J. Mammal. 2015, 96, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin-Wintle, M.S.; Shepherdson, D.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, H.; Li, D.; Zhou, X.; Li, R.; Swaisgood, R.R. Free mate choice enhances conservation breeding in the endangered giant panda. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jinchu, H. A study on the age and population composition of the giant panda by judging droppings in the wild. Acta Theriol. Sin. 2011, 7, 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, M.R.; Niemann, T.; Wark, J.D.; Heintz, M.R.; Horrigan, A.; Cronin, K.A.; Shender, M.A.; Gillespie, K. ZooMonitor (Version 1). [Mobile Application Software]. 2016. Available online: https://zoomonitor.org (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Bracke, M.B.M.; Hopster, H. Assessing the importance of natural behavior for animal welfare. J. Agric. Environ. Ethic 2006, 19, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistlberger, R.E.; Skene, D.J. Social influences on mammalian circadian rhythms: Animal and human studies. Biol. Rev. 1999, 79, 533–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wark, J.D.; Wierzal, N.K.; Cronin, K.A. Gaps in live inter-observer reliability testing of animal behavior: A retrospective analysis and path forward. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2021, 2, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.; Milanowski, A.; Miller, J. Measuring and promoting inter-rater agreement of teacher and principal performance ratings. Online Submission 2012. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED532068 (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Fávero, L.P.; Hair, J.F.; Souza, R.d.F.; Albergaria, M.; Brugni, T.V. Zero-inflated generalized linear mixed models: A better way to understand data relationships. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.G.; Wintle, B.A.; Rhodes, J.R.; Kuhnert, P.M.; Field, S.A.; Low-Choy, S.J.; Tyre, A.J.; Possingham, H. Zero tolerance ecology: Improving ecological inference by modelling the source of zero observations. Ecol. Lett. 2005, 8, 1235–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindén, A.; Mäntyniemi, S. Using the negative binomial distribution to model overdispersion in ecological count data. Ecology 2011, 92, 1414–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, M.E.; Kristensen, K.; Van Benthem, K.J.; Magnusson, A.; Berg, C.W.; Nielsen, A.; Skaug, H.J.; Machler, M.; Bolker, B.M. glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. R J. 2017, 9, 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brooks, M.E.; Kristensen, K.; Darrigo, M.R.; Rubim, P.; Uriarte, M.; Bruna, E.; Bolker, B.M. Statistical modeling of patterns in annual reproductive rates. Ecology 2019, 100, e02706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gandia, K.M.; Kessler, S.E.; Buchanan-Smith, H.M. Latitudinal and zoo specific zeitgebers influence circadian and circannual rhythmicity of behavior in captive giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca). Front. Psychol. 2023. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Lenth, R.V. Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Grinsted, A.; Moore, J.C.; Jevrejeva, S. Application of the cross wavelet transform and wavelet coherence to geophysical time series. Nonlinear Process. Geophys. 2004, 11, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hull, V.; Ouyang, Z.; He, L.; Connor, T.; Yang, H.; Huang, J.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, C.; et al. Modeling activity patterns of wildlife using time-series analysis. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 2575–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Liu, D.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, G.; Wei, R.; Hou, R. Exposure to odors of rivals enhances sexual motivation in male giant pandas. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charlton, B.D.; Owen, M.A.; Zhang, H.; Swaisgood, R.R. Scent anointing in mammals: Functional and motivational in-sights from giant pandas. J. Mammal. 2020, 101, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.M.; Swaisgood, R.R.; Zhang, H. The highs and lows of chemical communication in giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca): Effect of scent deposition height on signal discrimination. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2002, 51, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainka, S.A.; Zhang, H. Daily activity of captive giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) at the wolong reserve. Zoo Biol. 1994, 13, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilorz, V.; Astiz, M.; Heinen, K.O.; Rawashdeh, O.; Oster, H. The concept of coupling in the mammalian circadian clock Network. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432, 3618–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddameedhi, S.; Selby, C.P.; Kaufmann, W.K.; Smart, R.C.; Sancar, A. Control of skin cancer by the circadian rhythm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 18790–18795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, M.R.; Opp, M.R. Sleep health: Reciprocal regulation of sleep and innate immunity. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 42, 129–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nie, Y.; Speakman, J.R.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Hu, Y.; Xia, M.; Yan, L.; Hambly, C.; Wang, L.; Wei, W.; et al. Exceptionally low daily energy expenditure in the bamboo-eating giant panda. Science 2015, 349, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firsov, D.; Tokonami, N.; Bonny, O. Role of the renal circadian timing system in maintaining water and electrolytes homeostasis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012, 349, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, X.; Li, G.; Jiang, Y.; He, M.; Wang, C.; Gu, Y.; Ling, S.; Cao, S.; Wen, Y.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Skin mycobiota of the captive giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) and the distribution of opportunistic dermatomycosis-associated fungi in different seasons. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 708077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieger, I. Scent rubbing in carnivores. Carnivore 1979, 2, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Yuan, H.; Tian, H.; Wei, R.; Zhang, G.; Sun, L.; Wang, L.; Sun, R. Do anogenital gland secretions of giant panda code for their sexual ability? Chin. Sci. Bull. 2006, 51, 1986–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agatsuma, R.; Ramenofsky, M. Migratory behaviour of captive white-crowned sparrows, Zonotrichia leucophrys gambelii, differs during autumn and spring migration. Behaviour 2006, 143, 1219–1240. [Google Scholar]

- Clubb, R.; Mason, G. Captivity effects on wide-ranging carnivores. Nature 2003, 425, 473–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroshko, J.; Clubb, R.; Harper, L.; Mellor, E.; Moehrenschlager, A.; Mason, G. Stereotypic route tracing in captive Carnivora is predicted by species-typical home range sizes and hunting styles. Anim. Behav. 2016, 117, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, X.; Cheng, X.; Skidmore, A.K. Potential solar radiation pattern in relation to the monthly distribution of giant pandas in Foping Nature Reserve, China. Ecol. Model. 2011, 222, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Hong, M.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, J.; Hull, V.; Huang, J.; Zhang, H. Giant panda foraging and movement patterns in response to bamboo shoot growth. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 8636–8643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, M.S.; Owen, M.; Wintle, N.J.P.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, H.; Swaisgood, R.R. Stereotypic behaviour predicts reproductive performance and litter sex ratio in giant pandas. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.; Yngvesson, J.; Boissy, A.; Uvnäs-Moberg, K.; Lidfors, L. Behavioural expression of positive anticipation for food or opportunity to play in lambs. Behav. Process. 2015, 113, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, L.; Buchanan-Smith, H.M. Effects of predictability on the welfare of captive animals. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 102, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waitt, C.; Buchanan-Smith, H.M. What time is feeding? How delays and anticipation of feeding schedules affect stump-tailed macaque behavior. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2001, 75, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.V.; Nelson, O.L.; Robbins, C.T.; Jansen, H.T. Temporal organization of activity in the brown bear (Ursus arctos): Roles of circadian rhythms, light, and food entrainment. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Com-Parative Physiol. 2012, 303, R890–R902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Goede, P.; Sen, S.; Oosterman, J.E.; Foppen, E.; Jansen, R.; la Fleur, S.E.; Challet, E.; Kalsbeek, A. Differential effects of diet composition and timing of feeding behavior on rat brown adipose tissue and skeletal muscle peripheral clocks. Neurobiol. Sleep Circadian Rhythm. 2018, 4, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbe, I.; Leinweber, B.; Brandenburger, M.; Oster, H. Circadian clock network desynchrony promotes weight gain and alters glucose homeostasis in mice. Mol. Metab. 2019, 30, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasu, N.N.; Kurosawa, G.; Tokuda, I.T.; Mochizuki, A.; Todo, T.; Nakamura, W. Circadian regulation of food-anticipatory activity in molecular clock–deficient mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Umemura, Y.; Yagita, K. Development of the circadian core machinery in mammals. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432, 3611–3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohta, H.; Honma, S.; Abe, H.; Honma, K.-I. Effects of nursing mothers onrPer1andrPer2circadian expressions in the neonatal rat suprachiasmatic nuclei vary with developmental stage. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2002, 15, 1953–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, K.A.; Burr, R.L.; Spieker, S. Light and maternal influence in the entrainment of activity circadian rhythm in infants 4–12 weeks of age. Sleep Biol. Rhythm. 2016, 14, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tsai, S.-Y.; Barnard, K.E.; Lentz, M.J.; Thomas, K.A. Mother-infant activity synchrony as a correlate of the emergence of circadian rhythm. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2010, 13, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honma, S. Development of the mammalian circadian clock. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2018, 51, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, G.Q.; Swaisgood, R.R.; Wei, R.P.; Zhang, H.M.; Han, H.Y.; Li, D.S.; Wu, L.F.; White, A.M.; Lindburg, D.G. A method for encouraging maternal care in the giant panda. Zoo Biol. 2000, 19, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.C.; Litchfield, C.A. Impact of an enclosure rotation on the activity budgets of two captive giant pandas: An ob-servational case study. Eat Sleep Work 2020, 1, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swaisgood, R.R.; White, A.M.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, G.; Wei, R.; Hare, V.J.; Tepper, E.M.; Lindburg, D.G. A quantitative assessment of the efficacy of an environmental enrichment programme for giant pandas. Anim. Behav. 2001, 61, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, G.; Wei, R.; Zhang, H.; Fang, J.; Sun, R. Behavioral responsiveness of captive giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) to substrate odors from conspecifics of the opposite sex. In Chemical Signals in Vertebrates; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, M.A.; Swaisgood, R.R.; McGeehan, L.; Zhou, X.; Lindburg, D.G. Dynamics of male-female multimodal signaling behavior across the estrous cycle in giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca). Ethology 2013, 119, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wang, Z.; Tian, H.; Yu, C.; Zhang, G.; Wei, R.; Zhang, H. Behavior of giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) in captive conditions: Gender differences and enclosure effects. Zoo Biol. 2003, 22, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaisgood, R.R.; White, A.M.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, G.; Lindburg, D.G. How do giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) respond to varying properties of enrichments? A comparison of behavioral profiles among five enrichment items. J. Comp. Psychol. 2005, 119, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, R.J.; Perdue, B.M.; Zhang, Z.; Maple, T.L.; Charlton, B.D. Giant panda maternal care: A test of the experience constraint hypothesis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Zoo | Panda | Sex | Life Stage | Feeding Schedule | Mating Opportunity | Camera Visibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1 | F | Adult | On average, 9 (female) or 10 (male) times a day between 0700 and 1800 h | Around March; either natural or via artificial insemination | Daylight |

| 2 | M | Adult | ||||

| B | 3 | F | Sub-adult | Unknown | Breeding pair, but unknown time and method | 24 h |

| 4 | M | Sub-adult | ||||

| C | 5a | F | Sub-adult | First bamboo feed by 0900 h, second at 1200 h, third between 1330 and 1430 h, and final between 1530 and 1630 h | None | Daylight |

| 5b | F | Sub-adult | ||||

| 6a | F | Adult | Post-reproductive | |||

| 6b | M | Adult | ||||

| D | 7 | F | Sub-adult | First bamboo feed between 0745 and 0845 h, second before 1200 h, and final between 1300 and 1700 h | Around March; natural | 24 h |

| 8 | M | Adult | ||||

| E | 9 | M | Adult | First bamboo feed between 0800 and 1000 h, second around 1300 h, and final between 1700 and 1800 h | Castrated for medical reasons | 24 h |

| F | 10 | F | Maternal | Bamboo provided approximately 5× per day, with first feeding at 0730 h and final feeding between 1330 and 1400 h | N/A | 24 h |

| 11 | M | Cub |

| Behavior Category | Regression Type | Iterations | AIC | BIC | Df (Residual) | Dispersion Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | Linear | 58 | 13,484.6 | 13,631 | 2566 | 3.22 |

| Resting/sleeping | Quadratic | 60 | 15,680 | 15,826.4 | 2566 | 3.7 |

| Feeding | Linear | 57 | 10,541.2 | 10,687.6 | 2566 | 2.56 |

| Drinking | Linear | 51 | 1456 | 1602.4 | 2566 | 0.238 |

| Locomotion | Quadratic | 49 | 4594.3 | 4740.7 | 2566 | 0.33 |

| Pacing | Quadratic | 54 | 2421.1 | 2567.5 | 2566 | 2 |

| Bipedal standing | Quadratic | 49 | 580.9 | 727.3 | 2566 | 0.33 |

| Scent anointing | Quadratic | 55 | 298 | 444.4 | 2566 | 2.52 |

| Anogenital rubbing | Quadratic | 40 | 434.9 | 546.2 | 2569 | 0.224 |

| Female activity | Quadratic | 52 | 6407.2 | 6493.8 | 1192 | 4.82 |

| Maternal | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Nursing | Quadratic | 38 | 613.1 | 688.7 | 621 | 1.18 |

| In contact | Quadratic | 40 | 1722.6 | 1798.2 | 621 | 1.07 |

| Proximate | Quadratic | 41 | 2310.6 | 2386.2 | 621 | 1.67 |

| Distant | Linear | 38 | N/A | N/A | 621 | 1.12 |

| Conditional Model | Zero-Inflated Model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior | Variable | Coefficient | Z-Value | Pr (>|z|) | Variable | Coefficient | Z-Value | Pr (>|z|) |

| Activity | Summer | −0.057 | −2.250 | 0.025 | Summer | 0.155 | 2.213 | 0.027 |

| Winter | 0.063 | −2.250 | 0.025 | Autumn | 0.213 | 2.850 | 0.004 | |

| Cub | −0.105 | −2 | 0.046 | Spring | −0.320 | −4.540 | <0.001 | |

| Maternal | 0.118 | 2.390 | 0.017 | Maternal | −0.481 | −1.984 | 0.047 | |

| Hour | −0.016 | −2.410 | 0.016 | |||||

| Resting/sleeping | Spring | −0.064 | −2.674 | 0.008 | Spring | 0.214 | 2.926 | 0.003 |

| Autumn | −0.314 | −3.737 | <0.001 | |||||

| Summer | −0.209 | −2.687 | 0.007 | |||||

| Winter | 0.310 | 4.213 | <0.001 | |||||

| Hour | 0.020 | 2.815 | 0.005 | |||||

| Adult | 0.197 | 2.231 | 0.026 | |||||

| Cub | −0.506 | −3.797 | <0.001 | |||||

| Maternal | 0.697 | 5.925 | <0.001 | |||||

| Sub-adult | −0.387 | −4.628 | <0.001 | |||||

| Feeding | Adult | 0.177 | 2.590 | 0.010 | Autumn | 0.221 | 2.886 | 0.004 |

| Cub | −0.376 | −3.370 | <0.001 | Winter | −0.189 | −2.683 | 0.007 | |

| Hour | 0.007 | 2.460 | 0.014 | Spring | −0.244 | −3.534 | <0.001 | |

| Winter * | 0.045 | 1.800 | 0.072 | Summer | 0.212 | 2.950 | 0.003 | |

| Hour | −0.030 | −4.565 | <0.001 | |||||

| Cub * | 0.403 | 1.801 | 0.072 | |||||

| Drinking | Cub * | −2.094 | −1.813 | 0.070 | Spring | −0.536 | −2.268 | 0.023 |

| Summer | 0.532 | 2.345 | 0.019 | |||||

| Hour * | −0.043 | −1.761 | 0.078 | |||||

| Male * | 0.459 | 1.727 | 0.084 | |||||

| Locomotion | Winter | 0.223 | 2.545 | 0.011 | Spring | −1.040 | −2.710 | 0.007 |

| Summer | −0.199 | −2.163 | 0.031 | Sub-adult | 0.953 | 2.205 | 0.027 | |

| Hour | −0.071 | −5.932 | <0.001 | Hour | −0.494 | −7.104 | <0.001 | |

| Adult * | −0.559 | −1.774 | 0.076 | Winter * | 0.570 | 1.840 | 0.066 | |

| Cub * | −0.869 | −1.805 | 0.071 | |||||

| Pacing | Spring | 0.251 | 2.460 | 0.014 | Spring | −0.365 | −2.937 | 0.003 |

| Maternal | 1.546 | 1.999 | 0.046 | Summer | 0.298 | 1.970 | 0.049 | |

| Hour | −0.041 | −2.058 | 0.040 | Hour | 0.051 | 3.890 | <0.001 | |

| Cub * | −3.565 | −1.750 | 0.080 | |||||

| Bipedal standing | Spring | 1.071 | 3.265 | 0.001 | Winter | −1.373 | −2.586 | 0.010 |

| Hour | 0.400 | 5.028 | <0.001 | Autumn | 1.383 | 1.916 | 0.055 | |

| Hour | 0.631 | 6.423 | <0.001 | |||||

| Scent anointing | Hour | 0.397 | 4.822 | <0.001 | Hour | 0.790 | 3.098 | 0.002 |

| Male | −1.477 | −2.028 | 0.043 | Summer * | −1.940 | −1.710 | 0.087 | |

| Anogenital rubbing | Spring | 1.054 | 2.510 | 0.012 | Autumn | 2.489 | 2.218 | 0.027 |

| Summer | −3.023 | −4.047 | <0.001 | Summer | −5.262 | −2.467 | 0.014 | |

| Hour | 0.221 | 3.406 | 0.001 | Hour | 0.412 | 3.406 | <0.001 | |

| Female * | 0.973 | 1.823 | 0.068 | Female | 2.056 | 2.406 | 0.016 | |

| Male | −2.680 | −2.799 | 0.005 | |||||

| Winter * | 1.900 | 1.850 | 0.064 | |||||

| Conditional Model | Zero-Inflated Model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior | Variable | Coefficient | Z-Value | Pr (>|z|) | Variable | Coefficient | Z-Value | Pr (>|z|) |

| Female activity | Maternal female * | 0.105 | 1.750 | 0.08 | Maternal female * | −0.684 | −1.672 | 0.0945 |

| Maternal behaviors | N/A | N/A | ||||||

| Nursing | None | Hour | 0.059 | 2.370 | 0.018 | |||

| In contact | Spring 22 | −0.481 | −2.030 | 0.0420 | Spring 22 | −0.630 | −1.995 | 0.046 |

| Summer 21 | 0.534 | 3.185 | 0.001 | |||||

| Proximate | Autumn 21 | −0.618 | −4.473 | <0.001 | Spring 21 | 0.557 | 2.918 | 0.004 |

| Spring 22 | 0.448 | 2.968 | 0.003 | Spring 22 | −0.687 | −2.398 | 0.016 | |

| Summer 21 | −0.594 | −4.163 | <0.001 | Summer 21 | 0.415 | 2.065 | 0.039 | |

| Hour | 0.059 | 4.333 | <0.001 | |||||

| Winter 20–21 * | 0.436 | 1.802 | 0.072 | |||||

| Distant | Autumn 21 | 0.067 | 1.980 | 0.047 | Autumn 21 | −1.161 | −3.802 | <0.001 |

| Spring 21 | 0.091 | 2.740 | 0.006 | Winter 20–21 | 0.640 | 2.802 | 0.005 | |

| Spring 22 | −0.161 | −2.700 | 0.007 | Hour | −0.044 | −3.026 | 0.002 | |

| Summer 21 * | 0.061 | 1.790 | 0.073 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gandia, K.M.; Herrelko, E.S.; Kessler, S.E.; Buchanan-Smith, H.M. Understanding Circadian and Circannual Behavioral Cycles of Captive Giant Pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) Can Help to Promote Good Welfare. Animals 2023, 13, 2401. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13152401

Gandia KM, Herrelko ES, Kessler SE, Buchanan-Smith HM. Understanding Circadian and Circannual Behavioral Cycles of Captive Giant Pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) Can Help to Promote Good Welfare. Animals. 2023; 13(15):2401. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13152401

Chicago/Turabian StyleGandia, Kristine M., Elizabeth S. Herrelko, Sharon E. Kessler, and Hannah M. Buchanan-Smith. 2023. "Understanding Circadian and Circannual Behavioral Cycles of Captive Giant Pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) Can Help to Promote Good Welfare" Animals 13, no. 15: 2401. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13152401

APA StyleGandia, K. M., Herrelko, E. S., Kessler, S. E., & Buchanan-Smith, H. M. (2023). Understanding Circadian and Circannual Behavioral Cycles of Captive Giant Pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) Can Help to Promote Good Welfare. Animals, 13(15), 2401. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13152401