Sensory Stimulation as a Means of Sustained Enhancement of Well-Being in Leopard Geckos, Eublepharis macularius (Eublepharidae, Squamata)

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

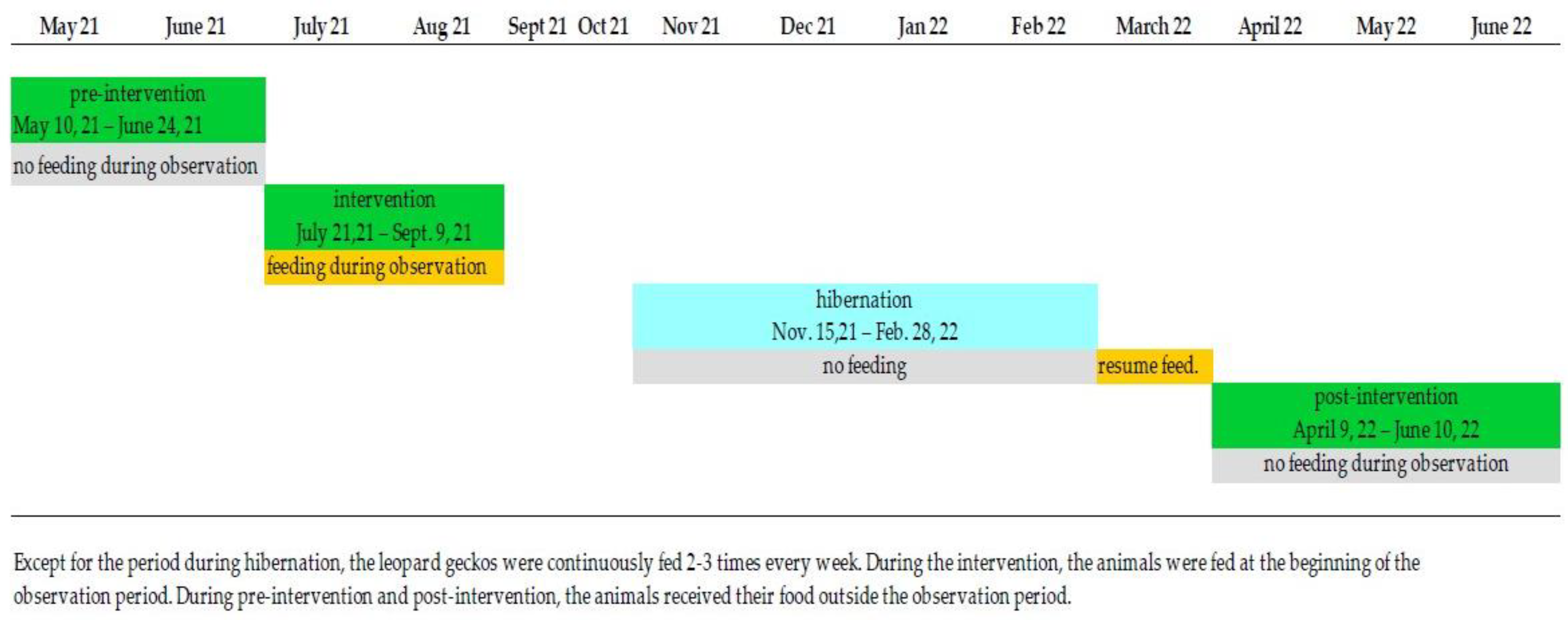

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Behavioural Observations

2.3. Ethogram

2.4. Study Animals

2.5. Housing and Husbandry

2.6. Sex

2.7. Feeding Insects

- House crickets, Acheta domesticus; field crickets, Gryllus assimilisThey quickly seek a hiding place, move quickly in intervals, congregate in warm places, spend more time under a cover than in open space, move mostly on the ground and are active during the day and in darkness; field crickets were less active than the house crickets.

- Desert locust, Schistocerca gregariaDuring the day, they often stay out of the cover, and they hide at dusk and during the night; they move slowly or jump, climb on all kinds of elevated points and gather in warm places.

- Housefly, Musca domesticaThey are incapable of flying, they do not seek out hiding places, they distribute themselves over all surfaces, are active above all during the day and gather in warm places. Their inability to fly is due to a defect mutation and it is common in the reptile feed market.

2.8. Forceps Feeding

2.9. Intrinsic Rhythms

2.10. Technical Equipment

2.11. Statistical Analysis

2.12. Qualitative Data

3. Results

3.1. Sensory Stimulation as a Means of Sustained Enhancement of Well-Being

3.2. Details Related to Co-Variables

3.2.1. Sex

3.2.2. Food Insects

3.2.3. Forceps Feeding

3.2.4. Terrarium Size

3.2.5. Body Temperature

3.2.6. Qualitative Data

3.2.7. Activity Time

4. Discussion

4.1. Differences Compared to Other Leopard Gecko Studies

- 1.

- 2.

- The quality and quantity of enclosures have significant impacts on the behaviours and welfare of the animals [87,88]. A change in the behavioural diversity or time budgets may be due to changes in the environment (e.g., a new terrarium) and need not have any impact on its welfare [31] but may nevertheless influence future behavioural expressions. It was shown, for example, in trouts (Oncorhychus mykiss), that enriched tanks promoted a better recovery from stress [95]. For corn snake (Pantherophis guttatus) and rat snake (Pantherophis obsoletus), it could be shown in different studies that a more structured terrarium leads to the animals having more interest in new objects, being better at problem solving and showing more explorative behaviour, greater behavioural intensity and well-being [41,42,43].

- 3.

- 4.

- Small, minimalistic terrariums inherently limit the opportunities for action as they offer little choice to act out behavioural preferences and often act as severe stressors on the animals [9,22,26,33,55,81,91,93]. A study with laboratory rats (Rattus norvegicus) has shown that animals that were exposed to an increase in stimulus diversity through enrichment were better habituated and performed better in cognitive tests, had better spatial memory and object recognition and explored more. In other words, they were better off than the controls, and had a better welfare level. Furthermore, the release of some neurochemical parameters, like acetylcholine, was also reduced, which indicates reduced perceived distress [97]. A study with zebrafish [33] has shown that animals that were kept under typical laboratory conditions (small barren tanks) regularly exhibited abnormal behaviours, increased sensitivity to stress-inducing factors, lethargy, restriction of normal behavioural repertoire and other negative effects. Conversely, zebrafish that were kept under more complex and stimulating conditions were shown to have a higher rate of brain cell proliferation, faster learning or higher stress tolerance. Thus, animals in complex and stimulating environments provide more realistic, valid and valuable models for scientific interventions [98].

4.2. Resource and Animal Based Factors

4.3. What Types of Behaviour Did the Leopard Geckos Display, and Can Indicators Regarding Their Well-Being Be Derived from This?

4.4. Other Correlations

4.4.1. Housing

4.4.2. Behavioural Diversity and Well-Being

- 1.

- Even without actual stimuli, the increase in the behavioural intensity (behavioural units) was still significant 11 months after the enrichment, exhibiting twice the level of activity compared to the baseline.

- 2.

- As cited in Materials and Methods, there were neither behavioural signs of reduced well-being nor any changes made to the high housing and husbandry quality.

- 3.

- As highlighted by Burghardt [7] and Warwick et al. [92], due to their ectothermic metabolisms, the activity levels of reptiles are different to those of mammals or birds [114]; however, the model of broad behavioural diversity as an indicator of good welfare was built on research on endotherms [5,6,7,8].

- 4.

- The long observation time of this study indicates the high reliability of the data.

4.5. Was It Trivial to Conduct This Study?

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Binding, S.; Farmer, H.; Krusin, L.; Cronin, K. Status of Animal Welfare Research in Zoos and Aquariums: Where Are We, Where to Go Next? JZAR 2020, 8, 166–174. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, J.C.E. Programmatic Approaches to Assessing and Improving Animal Welfare in Zoos and Aquariums. Zoo Biol. 2009, 28, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackett, T.A.; McKenna, C.; Kavanagh, L.; Morgan, D.R. The Welfare of Wild Animals in Zoological Institutions: Are We Meeting Our Duty of Care? Int. Zoo Yearb. 2017, 51, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.; Sherwen, S.L.; Robbins, R.; McLelland, D.J.; Whittaker, A.L. Welfare Assessment Tools in Zoos: From Theory to Practice. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melfi, V.A. There Are Big Gaps in Our Knowledge, and Thus Approach, to Zoo Animal Welfare: A Case for Evidence-Based Zoo Animal Management. Zoo Biol. 2009, 28, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosier, R.L.; Langkilde, T. Does Environmental Enrichment Really Matter? A Case Study Using the Eastern Fence Lizard, Sceloporus Undulatus. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 131, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, G.M. Environmental Enrichment and Cognitive Complexity in Reptiles and Amphibians: Concepts, Review, and Implications for Captive Populations. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2013, 147, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moszuti, S.A.; Wilkinson, A.; Burman, O.H.P. Response to Novelty as an Indicator of Reptile Welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 193, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn, A.L. A Review of Welfare Assessment Methods in Reptiles, and Preliminary Application of the Welfare Quality Protocol to the Pygmy Blue-Tongue Skink, Tiliqua Adelaidensis, Using Animal-Based Measures. Animals 2019, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagan, T. Evaluation of Enrichment for Reptiles in Zoos. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2019, 22, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomé, A.; Carazo, P.; Font, E. Environmental Enrichment for Reptiles in European Zoos: Current Status and Perspectives. Anim. Welf. 2023, 32, e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, K. Folklore Husbandry and a Philosophical Model for the Design of Captive Management Regimes. Herpetol. Rev. 2013, 44, 448–452. [Google Scholar]

- Whitham, J.C.; Wielebnowski, N. New Directions for Zoo Animal Welfare Science. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2013, 147, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrel, A.; van der Meijden, A. An Analysis of the Live Reptile and Amphibian Trade in the USA Compared to the Global Trade in Endangered Species. Herpetol. J. 2014, 24, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Schuppli, C.; Fraser, D.; Bacon, H. Welfare of Non-Traditional Pets. In Wild and Exotic Animals as Pets Collection; WellBeing International: Potomac, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Warwick, C. The Morality of the Reptile Pet Trade. J. Anim. Ethics 2014, 4, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warwick, C. Reptilian Ethology in Captivity: Observations of Some Problems and an Evaluation of Their Aethology. Part II: Findings and Discussion. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1990, 26, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, D. Setting the Scene: When Coping Is Not Enough: Promoting Positive Welfare States in Animals. In Proceedings of the RSPCA Australia: Scientific Seminar 2013, Proceedings, When Coping Is Not Enough. Promoting Positive Welfare States in Animals, Canberra, Australia, 26 February 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, D. Positive Animal Welfare States and Encouraging Environment-Focused and Animal-to-Animal Interactive Behaviours. N. Z. Vet. J. 2015, 63, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veasey, J.S. In Pursuit of Peak Animal Welfare; the Need to Prioritize the Meaningful over the Measurable. Zoo Biol. 2017, 36, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, P.E.; Nash, S.M.; Riley, L.M. To Pace or Not to Pace? A Review of What Abnormal Repetitive Behavior Tells Us about Zoo Animal Management. J. Vet. Behav. 2017, 20, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendyk, R.W.; Augustine, L. Controlled Deprivation and Enrichment. In Health and Welfare of Captive Reptiles; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 323–355. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, J. A Veterinary Perspective of Potential Risk Factors in Environmental Enrichment. In Second Nature. Environmental Enrichment for Captive Animals; Shepherdson, D.J., Mellen, J.D., Hutchins, M., Eds.; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA; London, UK, 1998; pp. 277–301. [Google Scholar]

- Young, R.J. Environmental Enrichment for Captive Animals; Universities Federation for Animal Welfare (UFAW); Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Boissy, A.; Manteuffel, G.; Jensen, M.B.; Moe, R.O.; Spruijt, B.; Keeling, L.J.; Winckler, C.; Forkman, B.; Dimitrov, I.; Langbein, J.; et al. Assessment of Positive Emotions in Animals to Improve Their Welfare. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 375–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, F. Cognitive Enrichment and Welfare: Current Approaches and Future Directions. Anim. Behav. Cogn 2017, 4, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, M.S. The Science of Animal Welfare: Understanding What Animals Want; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-0-19-884898-1. [Google Scholar]

- Browning, H. The Natural Behavior Debate: Two Conceptions of Animal Welfare. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2020, 23, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Learmonth, M.J. Dilemmas for Natural Living Concepts of Zoo Animal Welfare. Animals 2019, 9, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellor, D. Enhancing Animal Welfare by Creating Opportunities for Positive Affective Engagement. N. Z. Vet. J. 2015, 63, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watters, J.V.; Krebs, B.L.; Eschmann, C.L. Assessing Animal Welfare with Behavior: Onward with Caution. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2021, 2, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, D.L. Sensory Stimulation as Environmental Enrichment for Captive Animals: A Review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 118, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G.; Franks, B. Zebrafish Welfare: Natural History, Social Motivation and Behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 200, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, K.; Sherwen, S.L.; Larsen, H. Natural Habitat Design for Zoo-Housed Elasmobranch and Teleost Fish Species Improves Behavioural Repertoire and Space Use in a Visitor Facing Exhibit. Animals 2021, 11, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfensohn, S.; Shotton, J.; Bowley, H.; Davies, S.; Thompson, S.; Justice, W.S.M. Assessment of Welfare in Zoo Animals: Towards Optimum Quality of Life. Animals 2018, 8, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krönke, F. Beispiel Für Enrichment-Strategien Bei Reptilien. Reptilia 2021, 151, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherdson, D.J. Tracing the Path of Environmental Enrichment in Zoos. In Second Nature. Environmental Enrichment for Captive Animals; Shepherdson, D.J., Mellen, J.D., Hutchins, M., Eds.; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA; London, UK, 1998; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lindburg, D.G. Enrichment of Captive Mammals through Provisioning. In Second Nature. Environmental Enrichment for Captive Animals; Shepherdson, D.J., Mellen, J.D., Hutchins, M., Eds.; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA; London, UK, 1998; pp. 262–276. [Google Scholar]

- Mench, J.A. Environmental Enrichment and the Importance of Exploratory Behaviour. In Second Nature. Environmental Enrichment for Captive Animals; Shepherdson, D.J., Mellen, J.D., Hutchins, M., Eds.; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA; London, UK, 1998; pp. 30–46. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, K.N.; Line, S.W.; Markowitz, H. Zoos, Enrichment, and the Sceptical Observer: The Practical Value of Assessment. In Second Nature. Environmental Enrichment for Captive Animals; Shepherdson, D.J., Mellen, J.D., Hutchins, M., Eds.; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA; London, UK, 1998; pp. 153–171. [Google Scholar]

- Nagabaskaran, G.; Burman, O.H.P.; Hoehfurtner, T.; Wilkinson, A. Environmental Enrichment Impacts Discrimination between Familiar and Unfamiliar Human Odours in Snakes (Pantherophis guttatus). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 237, 105278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almli, L.M.; Burghardt, G.M. Environmental Enrichment Alters the Behaviour Profile of Ratsnakes (Elaphe). J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2006, 9, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoehfurtner, T.; Wilkinson, A.; Nagabaskaran, G.; Burman, O.H.P. Does the Provision of Environmental Enrichment Affect the Behaviour and Welfare of Captive Snakes? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 239, 105324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, C.C.; Thomson, A.J.C.; Cuculescu-Santana, M. Can Colored Object Enrichment Reduce the Escape Behavior of Captive Freshwater Turtles? Zoo Biol. 2020, 40, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, A.J.C.; Bannister, C.C.; Marshall, R.T.; McNeil, N.; Mear, D.M.; Lovick-Earle, S.; Cuculescu-Santana, M. Interest in Coloured Objects and Behavioural Budgets of Individual Captive Freshwater Turtles. J. Zoo Aquar. Res. 2021, 9, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanghae, H.; Thongprajukaew, K.; Inphrom, S.; Malawa, S.; Sandos, P.; Sotong, P.; Boonsuk, K. Enrichment Devices for Green Turtles (Chelonia Mydas) Reared in Captivity Programs. Zoo Biol. 2021, 40, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, Z.; Kother, G. Environmental Enrichment with Simple Puzzle Feeders Increases Feeding Time in Fly River Turtles (Carettochelys insculpta). Herpetol. Bull. 2015, 130, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Case, B.C.; Lewbart, G.A.; Doerr, P.D. The Physiological and Behavioural Impacts of and Preference for an Enriched Environment in the Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina carolina). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 92, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londoño, C.; Bartolomé, A.; Carazo, P.; Font, E. Chemosensory Enrichment as a Simple and Effective Way to Improve the Welfare of Captive Lizards. Ethology 2018, 124, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashaw, M.J.; Gibson, M.D.; Schowe, D.M.; Kucher, A.S. Does Enrichment Improve Reptile Welfare? Leopard Geckos (Eublepharis Macularius) Respond to Five Types of Environmental Enrichment. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 184, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, D. The Effect of Enrichment on Leopard Geckos (Eublepharis Macularius) Housed in Two Different Maintenance Systems (Rack System vs. Terrarium). Animals 2023, 13, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlstead, K. Determining the Cause of Stereotypic Behaviours in Zoo Carnivors. Toward Appropriate Enrichment Strategies. In Second Nature. Environmental Enrichment for Captive Animals; Shepherdson, D.J., Mellen, J.D., Hutchins, M., Eds.; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA; London, UK, 1998; pp. 172–183. [Google Scholar]

- Kreger, M.D.; Hutchins, M.; Fascione, N. Context, Ethics, and Environmental Enrichment in Zoos and Aquariums. In Second Nature. Environmental Enrichment for Captive Animals; Shepherdson, D.J., Mellen, J.D., Hutchins, M., Eds.; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA; London, UK, 1998; pp. 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Poole, T.B. Meeting a Mammal’s Psychological Needs. Basic Principles. In Second Nature. Environmental Enrichment for Captive Animals; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA; London, UK, 1998; pp. 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, D.; Patterson-Kane, E.; Stafford, K.J. The Sciences of Animal Welfare; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4443-0769-6. [Google Scholar]

- Young, R.J. The Importance of Food Presentation for Animal Welfare and Conservation. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1997, 56, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koene, P. When Feeding Is Just Eating: How Do Farm and Zoo Animals Use Their Spare Time? In Regulation of Feed Intake; van der Heide, D., Huisman, E.A., Kanis, E., Osse, J.W.M., Verstegen, M.W.A., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, K.N.; Tromborg, C.T. Sources of Stress in Captivity. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 102, 262–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duscha, D.; Drewes, O. Der Leopardgecko Und Seine Farbvarianten; Vivaria Verlag für Heimtierliteratur: Meckenheim, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tremper, R. Leopard Geckos. The Next Generation, 2nd ed.; Author’s Edition; LLLReptile and Supply Co., Inc.: Chandler, AZ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, R. Über Einige Seltene Eidechsen Aus West-Pakistan. DATZ 1959, 12, 307–310. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, D.; Tousignant, A.; Crews, D. Incubation Temperature Affects the Behavior of Adult Leopard Geckos (Eublepharis macularius). Physiol. Behav. 1994, 55, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tousignant, A.; Crews, D. Effect of Exogenous Estradiol Applied at Different Embryonic Stages on Sex Determination, Growth, and Mortality in the Leopard Gecko (Eublepharis macularius). J. Exp. Zool. 1994, 268, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kratochvíl, L.; Frynta, D. Body Size, Male Combat and the Evolution of Sexual Dimorphism in Eublepharid Geckos (Squamata: Eublepharidae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2002, 76, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, M.M.; Putz, O.; Crews, D.; Wade, J. Normally Occurring Intersexuality and Testosterone Induced Plasticity in the Copulatory System of Adult Leopard Geckos. Horm. Behav. 2005, 47, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janes, D.E.; Wayne, M.L. Evidence for a Genotype × Environment Interaction in Sex-Determining Response to Incubation Temperature in the Leopard Gecko, Eublepharis Macularius. Herpetologica 2006, 62, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferkin, M.; Ladage, L. Do Female Leopard Geckos (Eublepharis macularius) Discriminate between Previous Mates and Novel Males? Behaviour 2007, 144, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, K.E.; Vickaryous, M.K. A Novel Amniote Model of Epimorphic Regeneration: The Leopard Gecko, Eublepharis Macularius. BMC Dev. Biol. 2011, 11, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, I.; Bauer, A.M.; Gamble, T.; Giri, V.B.; Jablonski, D.; Khandekar, A.; Mohapatra, P.P.; Masroor, R.; Mishra, A.; Ramakrishnan, U. The Evolutionary History of an Accidental Model Organism, the Leopard Gecko Eublepharis Macularius (Squamata: Eublepharidae). Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2022, 168, 107414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torki, F. Distribution, Lifestyle, and Behavioural Aspects of the Iranian Fat-Tailed Gecko, Eublepharis Angramainyu Anderson and Leviton 1966. Gekko 2010, 6, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.S. Amphibians and Reptiles of Pakistan; Kriger Publishing Company: Malabar, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rawat, Y.B.; Thapa, K.B.; Bhattarai, S.; Shah, K.B. First Record of the Common Leopard Gecko, Eublepharis Macularius (Blyth 1854) (Eublepharidae), in Nepal. Reptiles Amphib. 2019, 26, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, S.A., Jr. A Contribution to the Herpetology of West Pakistan. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 1966, 134, 27–184. [Google Scholar]

- Seufer, H.; Kaverkin, Y. Die Lidgeckos. Pflege, Zucht Und Lebensweise; Kirschner, A., Ed.; Kirscher & Seufer Verlag: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.S. Natural History and Biology of Hobbyist Choice Leopard Gecko. Reptilia 2006, 57, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Brandstaetter, F. Observations on the Territory-Marking Behaviour of the Gecko Eublepharis Macularius. Hamadryad 1992, 17, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Henkel, F.W.; Knöthig, M.; Schmidt, W. Leopardgeckos; Natur und Tier-Verlag: Münster, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chiszar, D.; Tomlinson, W.T.; Smith, H.M.; Murphy, J.B.; Radcliffe, C.W. Behavioural Consequences of Husbandry Anipulations: Indicators of Arousal, Quiescence and Environmental Awareness. In Health and Welfare of Captive Reptiles; Warwick, C., Frye, F.L., Murphy, J.B., Eds.; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1995; pp. 186–204. [Google Scholar]

- The Oxford Handbook of Animal Ethics; Beauchamp, T.L.; Frey, R.G. (Eds.) Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm, H.; Wild, M. Tierethik Zur Einführung; Junius: Hamburg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, G.J.; Burn, C. Frustration and Boredom in Impoverished Environments. In Animal Welfare; Appleby, M.C., Olsson, A.S., Galindo, F., Eds.; CABI: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 114–138. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, B. Animal Ethics. A Contemporary Introduction; Routledge Contemporary Introductions to Philosophy; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Krönke, F. Enrichment in Der Terraristik. Reptilia 2021, 151, 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Krönke, F. In Welchen Bereichen Ist Enrichment Bei Reptilien Möglich? Reptilia 2021, 151, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, A.L.; Golder-Dewar, B.; Triggs, J.L.; Sherwen, S.L. Identification Od Animal-Based Welfare Indicators in Captive Reptiles: A Delphi Consulation Survey. Animals 2021, 11, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warwick, C.; Steedman, C. Naturalistic versus Clinical Environments in Husbandry and Research. In Health and Welfare of Captive Reptiles; Warwick, C., Frye, F.L., Murphy, J.B., Eds.; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1995; pp. 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Maple, T.; Perdue, B.M. Zoo Animal Welfare; Animal Welfare; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 14, ISBN 978-3-642-35954-5. [Google Scholar]

- Rees, P.A. Studying Captive Animals. A Workbook of Methods in Behaviour, Welfare and Ecology; Wiley Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, A.M. Geckos. The Animal Answer Guide; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, J.V. General Husbandry and Management. In Mader’s Reptile and Amphibian Medicine and Surgery; Divers, S.J., Stahl, S.J., Eds.; Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2019; pp. 109–130. [Google Scholar]

- Burghardt, G.M.; Layne, D.G. Effects of Ontogenetic Processes and Rearing Conditions. In Health and Welfare of Captive Reptiles; Warwick, C., Frye, F.L., Murphy, J.B., Eds.; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1995; pp. 165–204. [Google Scholar]

- Warwick, C.; Frye, F.L.; Murphy, J.B. (Eds.) Health and Welfare of Captive Reptiles; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sakata, J.T.; Gupta, A.; Chuang, C.-P.; Crews, D. Social Experience Affects Territorial and Reproductive Behaviours in Male Leopard Geckos, Eublepharis Macularius. Anim. Behav. 2002, 63, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jančúchová-Lásková, J.; Landová, E.; Frynta, D. Are Genetically Distinct Lizard Species Able to Hybridize? A Review. Curr. Zool. 2015, 61, 155–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pounder, K.C.; Mitchell, J.L.; Thomson, J.S.; Pottinger, T.G.; Buckley, J.; Sneddon, L.U. Does Environmental Enrichment Promote Recovery from Stress in Rainbow Trout? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 176, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandøe, P.; Corr, S.; Palmer, C. Companion Animal Ethics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-118-37669-0. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, J.; Kelly, J.P. The Impact of Environmental Enrichment in Laboratory Rats—Behavioural and Neurochemical Aspects. Behav. Brain Res. 2011, 222, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, I.A.S.; Nevison, C.M.; Patterson-Kane, E.G.; Sherwin, C.M.; Van der Weerd, H.A.; Würbel, H. Understanding behaviour: The relevance of ethological approaches in laboratory animal science. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2003, 81, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubrecht, R.C. The Welfare of Animals Used in Research: Practice and Ethics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-118-78304-7. [Google Scholar]

- Warwick, C.; Arena, P.; Lindley, S.; Jessop, M.; Steedman, A. Assessing Reptile Welfare Using Behavioural Criteria. Practice 2013, 35, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krönke, F.; Xu, L. Compromised well-being as result of successful enrichment in leopard geckos (Eublepharis macularius)? 2023; under submission. [Google Scholar]

- Yeates, J. How Happy Does a Happy Animal Have to Be (and How Can We Tell)? In Proceedings of the RSPCA Australia: Scientific Seminar 2013, Proceedings, When Coping Is Not Enough. Promoting Positive Welfare States in Animals, Canberra, Australia, 26 February 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, G.J.; Burn, C.C. Behavioural Restriction. In Animal Welfare; Appleby, M.C., Mench, J.A., Olsson, I.A.S., Hughes, B.O., Eds.; CABI: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 98–119. ISBN 978-1-78064-080-8. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, W.E.; DePerno, C.S.; Steele, L.J. Effects of Movement and Eating on Chemosensory Tongue-Flicking and on Labial-Licking in the Leopard Gecko (Eublepharis macularius). Chemoecology 1996, 7, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePerno, C.S.; Cooper, W.E. Labial-Licking for Chemical Sampling by the Leopard Gecko (Eublepharis macularius). J. Herpetol. 1996, 30, 540543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, G.J. Species Differences in Responses to Captivity: Stress, Welfare and the Comparative Method. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durso, A.M.; Maerz, J.C. Natural Behaviour. In Mader’s Reptile and Amphibian Medicine and Surgery; Divers, S.J., Stahl, S.J., Eds.; Elsevier: St. Louis, MI, USA, 2019; pp. 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, R.T.; Parker, M.R. Social Behavior and Pheromonal Communication in Reptiles. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2010, 196, 729–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, A.L.; Marsh, L.E. The Role of Behavioural Assessment in Determining “positive” Affective States in Animals. CABI Rev. 2019, 2019, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wemelsfelder, F.; Mullan, S. Applying Ethological and Health Indicators to Practical Animal Welfare Assessment: -EN- Applying Ethological and Health Indicators to Practical Animal Welfare Assessment -FR- L’utilisation d’indicateurs Éthologiques et Sanitaires Pour l’évaluation Concrète Du Bien-Être Animal -ES- Aplicación de Indicadores Etológicos y Sanitarios a La Evaluación Práctica Del Bienestar Animal. Rev. Sci. Tech. OIE 2014, 33, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, D.J.; Beausoleil, N.J. Extending the ‘Five Domains’ Model for Animal Welfare Assessment to Incorporate Positive Welfare States. Anim. Welf. 2015, 24, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, D. Updating Animal Welfare Thinking: Moving beyond the “Five Freedoms” towards “A Life Worth Living”. Animals 2016, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, B.; Noble, D.W.A.; Whiting, M.J. Learning in Non-avian Reptiles 40 Years on: Advances and Promising New Directions. Biol. Rev. 2021, 96, 331–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libourel, P.-A.; Herrel, A. Sleep in Amphibians and Reptiles: A Review and a Preliminary Analysis of Evolutionary Patterns: Sleep in Amphibians and Reptiles. Biol. Rev. 2016, 91, 833–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanty, N.P.; Wagener, C.; Herrel, A.; Thaker, M. The Ecology of Sleep in Non-avian Reptiles. Biol. Rev. 2022, 97, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veasey, J.S.; Waran, N.K.; Young, R.J. On Comparing the Behaviour of Zoo Housed Animals with Wild Conspecifics as a Welfare Indicator. Anim. Welf. 1996, 5, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alligood, C.; Dorey, N.R.; Mehrkam, L.R.; Leighty, K. Applying Behaviour-Analytic Methodology to the Science and Practice of Environmental Enrichment in Zoos and Aquariums. Zoo Biol. 2017, 36, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, P.E.; Riley, L.M. Conducting Behavioural Research in the Zoo: A Guide to Ten Important Methods, Concepts and Theories. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2021, 2, 421–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayers, M.P.; Jennings, M.R.; Mellen, J.D. Byond Mammals. Environmental Enrichment for Amphibians and Reptiles. In Second Nature. Environmental Enrichment for Captive Animals; Shepherdson, D.J., Mellen, J.D., Hutchins, M., Eds.; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA; London, UK, 1998; pp. 205–235. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, L.J.; Vicino, G.A.; Sheftel, J.; Lauderdale, L.K. Behavioral Diversity as a Potential Indicator of Positive Animal Welfare. Animals 2020, 10, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeates, J. Naturalness and Animal Welfare. Animals 2018, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R. Training Reptiles in Zoos: A Professional Perspective. In Zoo Animal Learning and Training; Melfi, V.A., Dorey, N.R., Ward, S.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons LTd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrkam, L.R.; Dorey, N.R. Is Preference a Predictor of Enrichment Efficacy in Galapagos Tortoises (Chelonoidis nigra)? Zoo Biol. 2014, 33, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, L.F.; Mello, H.E.S.; Young, R.J. Enriching Tortoises: Assessing Color Preference. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2014, 17, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Fischer, J. Das Terrarium, Seine Bepflanzung Und Bevölkerung.; Verlag von Mahlau & Waldschmidt: Frankfurt, Germany, 1884. [Google Scholar]

- Lachmann, H. Das Terrarium, Seine Einrichtung, Bepflanzung Und Bevölkerung; Creutz’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung: Magdeburg, Germany, 1888. [Google Scholar]

- Geyer, H. Katechismus Für Terrarienliebhaber. Fragen Und Antworten Über Einrichtung, Besetzung Und Pflege Des Terrariums; Creutz’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung: Magdeburg, Germany, 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Bade, E. Praxis Der Terrarienkunde (Terrarium Und Terra-Aquarium); Creutz’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung: Magdeburg, Germany, 1907. [Google Scholar]

- Krefft, P. Das Terrarium. Ein Handbuch Der Häuslichen Reptilien- Und Amphibienpflege; Fritz Pfenningstorff. Verlag für Sport und Naturliebhaberei: Berlin, Germany, 1907. [Google Scholar]

| Ethogram of the Leopard Gecko | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Abbreviation | Behavioural Categories | Definition | |

| resting behaviour I | |||

| 1. | hp | hiding place | resting within a hiding place, not active, complete body or for at least 2/3 of it not visible, head always hidden, no observation of the outside possible |

| 2. | ruc | rest under cover | animal is partly visible, cover is open at least at one side, observation of the outside is possible |

| sense of security | |||

| 3. | ro | rest outside | resting outside any hiding place or cover, not physically active, lasting at least 3 s, not the ordinary break between all behavioural units |

| 4. | rep | rest elevated place | rest most of the time outside cover at elevated structures like stones, roots, cork tubes |

| 5. | rec | rest eyes closed | resting with or without cover, with one or both eyes closed, indicating a sense of security |

| walking around (large movements) | |||

| 6. | wa | walk around | walk of at least one body length, mostly in connection with explorations |

| 7. | wasm | walk around slow motion | walking with a strongly reduced speed, mostly in context of prey capture, exploration or social contacts |

| 8. | clim | climbing | explorative or targeted action, both directions: up and down on a stone, root, etc. |

| sensory exploration | |||

| 9. | pa | position alteration | mostly isolated head movements but also position movements of the body without going a step, includes sensory perceptions like smelling or looking, which are sometimes difficult to detect |

| 10. | look | looking | sensory perception/exploration during any activity; head often follows a stimulus |

| 11. | sme | smelling | sensory perception/exploration during any activity; head often follows a stimulus and nose touches or becomes very close to the object of interest |

| 12. | tf | tongue flicking | consolidated category sensory perception/exploration during any activity, head often follows a stimulus and tongue touches the object of interest; also, after drinking or eating, sometimes tongue flicks into the air, and sometimes the mouth is opened and the tongue does not transcend the jawbone |

| interest | |||

| 13. | coo | change of body orientation | change of body orientation, with at least one leg moved, and body moves less than a whole body length, often a realignment of the body axis |

| 14. | rhp | rest in high position | at least the forelegs, and in some situations, also the hind legs, are strung out, often in combination with hu; if all 4 legs are strung out, it is not the classic fright reaction, which is directed to a threat it could last a few seconds to several minutes, probably an expression of interest and sensory perception/exploration directed toward a stimulus; sometimes with closed eyes |

| 15. | hu | head up | head is directed upward between 45 and 90°, often together with rhp, probably sensory perception/exploration directed toward a stimulus, e.g., tearflys walking on the ceiling of the terrarium |

| foraging behaviour | |||

| 16. | ttv | tail (tip) vibrations | all types of tail movements, mostly in context with prey or social contact |

| 17. | snap | snap | snap a prey, not a synonym with eat, because a snap can be unsuccessful |

| 18. | bj | bag jump | jump towards a prey in order to bag it |

| 19. | eat | eating | eat a prey |

| basic needs | |||

| 20. | drink | drinking | drink water |

| 21. | def | defecate | defecate |

| 22. | gape | gape | single wide opening of mouth, mostly at the beginning of activity period |

| 23. | cl | cloaca licking | cloaca licking |

| ambivalent behaviour | |||

| 24. | dig | digging | mostly near the front pane; single movements to construction of holes that can harbour the gecko |

| 25. | pw | pane walking | walking along the front pane; in some situations, this is a sign of low well-being |

| 26. | lop | look out pane | mostly front pane, probably an expression of interest and sensory perception/exploration, often together with pa, rhp, pw |

| Indication of distressed behaviour | |||

| 27. | ps | pane scratching | scratching at front pane or ventilation grid; clear sign of low well-being |

| 28. | vps | vertical pane standing | standing on hind legs at front pane, often together with scratching movements of forelegs, clear sign of low well-being, motivation to escape |

| 29. | rhp fp | resp high position at front pane | head is directed toward front pane or in angle of 90° to fp; in some situations, this is a sign of sensory perception/exploration, and in others, it is a sign of low well-being or motivation to escape if ps or vps are also shown in a temporal context |

| indication of low well-being | |||

| 30. | mpr | mouth at pane rubbing | often in combination with tf, sme, pa and coo, very short duration, rare, sensory perception/exploration, or sign of low well-being, with motivation to escape |

| 31. | wmp | wriggling movements at pane | always in combination with coo or pa, short in duration, rare, clear, discrete repetitive behaviour and sign of low well-being, acute stress and motivation to escape, exclusively in connection with front pane |

| resting behaviour II | |||

| resting, no behaviour (not counted) | little breaks (less than three seconds) in a behavioural sequence, respectively, the “stops“ between single behavioural elements | ||

| ID | Sex | Housing | Usable Space cm2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | m | single | 2500 |

| 2 | m | single | 2500 |

| 3 | m | single | 2500 |

| 4, 5 | f, f | pair | 5000 |

| 6 | m | single | 2500 |

| 7 | m | single | 4000 |

| 8, 9 | f, f | pair | 3200 |

| 10 | m | single | 3300 |

| 11, 12 | f, m | pair | 3300 |

| 13, 14 | f, m | pair | 7000 |

| 15, 16, 17, 18 | f, f, f, f | quartet | 21,000 |

| p-Values | Baseline_1_2 | Intervention_1_3 | Post-Intervention_2_3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| behavioural diversity | 0.070 | 0.116 | 0.005 |

| Baseline 1 | Intervention 2 | Post-intervention 3 | |

| average behaviours performed | 19.7 | 21.4 | 18.5 |

| range of variation | 11 | 12 | 11 |

| minimum | 14 | 15 | 14 |

| maximum | 25 | 27 | 25 |

| median | 19.5 | 21 | 18 |

| Table: Changes in Behavioural Quantity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Set | Sensory Exploration | Walking Around | Interest | All Resting Behaviour | |||

| Factor | Factor | Factor | |||||

| baseline | 5723 | - | 2431 | - | 1936 | - | 1848 |

| intervention | 13,477 | 2.35 | 5696 | 2.34 | 2914 | 1.51 | 1734 |

| post-intervention | 13,914 | 2.43 | 2323 | 0.96 | 3748 | 1.94 | 1793 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krönke, F.; Xu, L. Sensory Stimulation as a Means of Sustained Enhancement of Well-Being in Leopard Geckos, Eublepharis macularius (Eublepharidae, Squamata). Animals 2023, 13, 3595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13233595

Krönke F, Xu L. Sensory Stimulation as a Means of Sustained Enhancement of Well-Being in Leopard Geckos, Eublepharis macularius (Eublepharidae, Squamata). Animals. 2023; 13(23):3595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13233595

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrönke, Frank, and Lisa Xu. 2023. "Sensory Stimulation as a Means of Sustained Enhancement of Well-Being in Leopard Geckos, Eublepharis macularius (Eublepharidae, Squamata)" Animals 13, no. 23: 3595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13233595

APA StyleKrönke, F., & Xu, L. (2023). Sensory Stimulation as a Means of Sustained Enhancement of Well-Being in Leopard Geckos, Eublepharis macularius (Eublepharidae, Squamata). Animals, 13(23), 3595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13233595