Comparison of Police Data on Animal Cruelty and the Perception of Animal Welfare NGOs in Hungary

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Whether it was committed by ill-treatment or by mistreatment;

- Whether that action was justified;

- Whether it involved a risk of permanent damage to the animal’s health or its death;

- Whether particular suffering occurred.

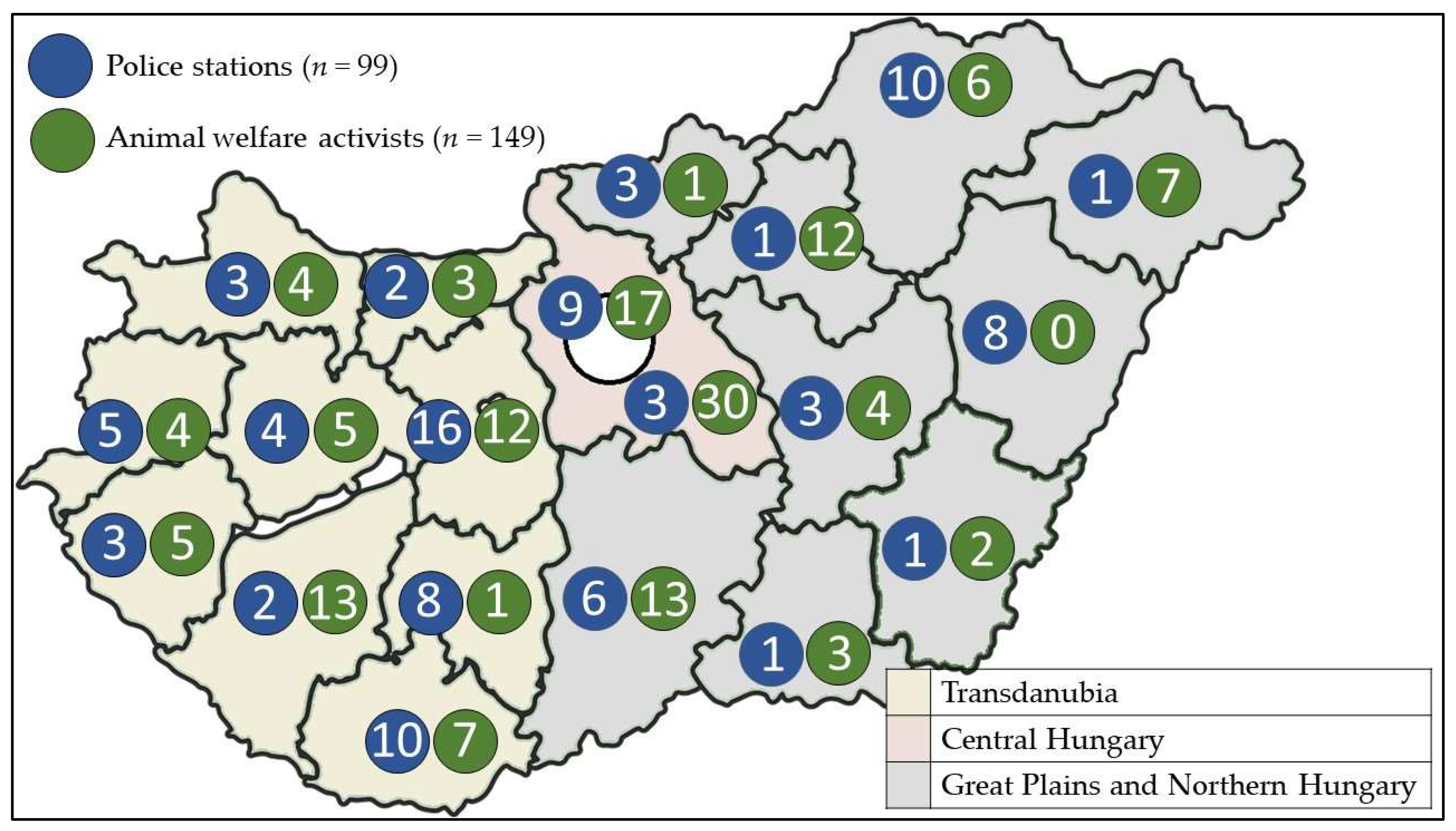

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Initiation of Criminal Investigations

3.2. The Importance of the Criminal Offence of Animal Cruelty

3.3. Investigating and Taking Evidence

3.4. The Opinion of Animal Welfare NGOs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Glanville, C.; Ford, J.; Coleman, G. Animal Cruelty and Neglect: Prevalence and Community Actions in Victoria, Australia. Animals 2019, 9, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reese, L.A.; Vertalka, J.J.; Richard, C. Animal cruelty and neighborhood conditions. Animals 2020, 10, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, H.; Dorr, L. Electronically available surveys of attitudes toward animals. Soc. Anim. 2000, 8, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shih, H.Y.; Paterson, M.B.; Phillips, C.J. A retrospective analysis of complaints to RSPCA Queensland, Australia, about dog welfare. Animals 2016, 9, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michel, M.; Kühne, D.; Hänni, J. Animal Law—Tier und Recht, Developments and Perspectives in the 21st Century, DIKE, Zurich. 2021. Available online: https://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~korsgaar/CMK.Animal.Rights.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Kant, I. Kants Gesammelte Schriften, 1st ed.; Georg Reimer: Berlin, Germany, 1900. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, N.T., Jr. Kant on Duties to Animals. Jarbuch Recht Ethik 2005, 13, 299–311. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, T.R. Should Trees Have Standing? Toward Legal Rights for Natural Objects. 2 Fla. State Univ. Law Rev. 1974, 2, 672–675. [Google Scholar]

- Galvin, S.L.; Herzog, H.A., Jr. Ethical ideology, animal rights activism, and attitudes toward the treatment of animals. Ethics Behav. 1992, 2, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reys, C.L. Animal Cruelty: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Understanding, 2nd ed.; Carolina Academic Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2013; pp. 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, G.J.; Mendl, M. Why is there no simple way of measuring animal welfare? Anim. Welf. 1993, 2, 301–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.; Lockwood, R. Investigating & Prosecuting Animal Abuse: A Guidebook on Safer Communities, Safer Families & Being an Effective Voice for Animal Victims. Alexandria, VA: National District Attorneys Association. 2013. Available online: https://ia903002.us.archive.org/15/items/InvestigatingAndProsecutingAnimalAbuse2013/Investigating%20and%20Prosecuting%20Animal%20Abuse%202013.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Merck, M. Veterinary Forensics: Animal Cruelty Investigations, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Ames, IA, USA, 2013; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E.; Stern, A.W. Veterinary Forensics: Investigation, Evidence Collection, and Expert Testimony, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 225–312. [Google Scholar]

- Otteman, K.; Fielder, L.; Lewis, E. Animal Cruelty Investigations: A Collaborative Approach from Victim to Verdict, 1st ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffer, T.; Hargreaves-Cormany, H.; Muirhead, Y.; Meloy, J.R. Violence in Animal Cruelty Offenders, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stafford, K.J.; Mellor, D.J. The implementation of animal welfare standards by Member Countries of the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE): Analysis of an OIE questionnaire. Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epizoot. 2009, 28, 1143–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsalve, S.; Ferreira, F.; Garcia, R. The connection between animal abuse and interpersonal violence: A review from the veterinary perspective. Res. Vet. Sci. 2017, 114, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkow, P. The relationships between animal abuse and other forms of family violence. Fam. Violence Sex. Assault Bull. 1996, 12, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, C.P. Woman’s best friend: Pet abuse and the role of companion animals in the lives of battered women. Violence Against Women 2000, 6, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, B.J.; Fitzgerald, A.; Stevenson, R.; Cheung, C.H. Animal maltreatment as a risk marker of more frequent and severe forms of intimate partner violence. J. Interpers. 2020, 325, 5131–5156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog Jr, H.A. “The movement is my life”: The psychology of animal rights activism. J. Soc. Issues 1993, 49, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Emotions, Morality, and Political Participation Behaviors in Online Activism. In The Power of Morality in Movements: Civic Engagement in Climate Justice, Human Rights, and Democracy, 1st ed.; Sevelsted, A., Toubøl, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 265–289. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, L.K.; Löfström, E.; Klöckner, C.A. Activist Art as a Motor of Change? How Emotions Fuel Change. In Disruptive Environmental Communication, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, K. ‘Anger is why we’re all here’: Mobilizing and managing emotions in a professional activist organization. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2010, 9, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieleke, M.; Goetz, T.; Yanagida, T.; Botes, E.; Frenzel, A.C.; Pekrun, R. Measuring emotions in mathematics: The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire—Mathematics (AEQ-M). ZDM Int. J. Math. Educ. 2022, 55, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsson, K.; Lindblom, J. Emotion work in animal rights activism: A moral-sociological perspective. Acta Sociol. 2013, 56, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H.A.; Golden, L.L. Moral emotions and social activism: The case of animal rights. J. Soc. Issues 2009, 65, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plous, S. An attitude survey of animal rights activists. Psychol. Sci. 1991, 2, 194–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Human League: How Animal Welfare Organizations Help Animals. 2021. Available online: https://thehumaneleague.org/article/animal-welfare-organizations (accessed on 29 May 2022).

- The Animal Wellness Institute: Our Work. 2021. Available online: https://www.theanimalwellnessinstitute.org/our-work (accessed on 29 May 2022).

- Animal Rights Foundation—Who We Are. Available online: https://www.animalrights.nl/animal-rights-who-we-are?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIx4D4yury9wIVUQGLCh3tuQmbEAAYBCAAEgLz7_D_BwE (accessed on 29 May 2022).

- Farm Animal Rights Movement (FARM): Who We Are. Available online: https://farmusa.org/?gclid=EAIaIQobChMI3KGtpOzy9wIVDZ53Ch12ggfrEAAYAyAAEgKS8PD_BwE (accessed on 29 May 2022).

- Lopez, J. Animal Welfare: Global Issues, Trends and Challenges. Scientific and Technical Review, Vol. 24 (2). Can. Vet. J. 2007, 48, 1163. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, P.; Battaglia, D.; Bullon, C.; Carita, A. Review of Animal Welfare Legislation in the Beef, Pork, and Poultry Industries. FAO Investment Centre. Directions in Investment (FAO), Rome. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i4002e/i4002e.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- European Commission. Special Report Animal Welfare in the EU: Closing the Gap between Ambitious Goals and Practical Implementation. 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/animals/animal-welfare/evaluations-and-impact-assessment/evaluation-eu-strategy-animal-welfare_en (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- European Food Safety Authority. Animal Welfare: Consultation Opens on Farm to Fork Guidance. 2022. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/news/animal-welfare-consultation-opens-farm-fork-guidance (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Protect The Harvest Non-Profit Corporation. Animal Extremism vs. Animal Welfare—There Is a Difference. Available online: https://protecttheharvest.com/what-you-need-to-know/animal-rights-vs-animal-welfare-there-is-a-difference/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Strand, P. What is Animal Welfare and Why Is It Important? National Animal Interest Alliance. 2014. Available online: https://www.naiaonline.org/articles/article/what-is-animal-welfare-and-why-is-it-important#sthash.wf1OD5fW.dpbs (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Rioja-Lang, F.; Bacon, H.; Connor, M.; Dwyer, C.M. Prioritisation of animal welfare issues in the UK using expert consensus. Vet. Rec. 2020, 187, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Animal Rights Activist Sentenced to 21 Months for Cross-Country Crime Spree Targeting Fur Industry. Available online: https://www.fbi.gov/contact-us/field-offices/sandiego/news/press-releases/animal-rights-activist-sentenced-to-21-months-for-cross-country-crime-spree-targeting-fur-industry (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Donovan, J.; Coupe, R.T. Animal rights extremism: Victimization, investigation and detection of a campaign of criminal intimidation. Eur. J. Criminol. 2013, 10, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccato, V.; Lundqvist, P.; Abraham, J.; Göransson, E.; Svennefelt, C.A. Farmers, Victimization, and Animal Rights Activism in Sweden. Prof. Geogr. 2022, 74, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, R. Political animals: A survey of the animal protection movement in Britain. Parliam. Aff. 1993, 46, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väärikkälä, S.; Hänninen, L.; Nevas, M. Veterinarians experience animal welfare control work as stressful. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arluke, A. Brute Force: Animal Police and the Challenge of Cruelty, 1st ed.; Purdue University Press: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J. Why Addressing Animal Cruelty Crimes Matters. Available online: https://www.police1.com/investigations/articles/why-addressing-animal-cruelty-crimes-matters-PKM36xqraV4fFrv2/ (accessed on 21 July 2022).

- Addressing and Preventing Animal Cruelty in NYC. Available online: https://www.aspca.org/investigations-rescue/addressing-and-preventing-animal-cruelty-nyc (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Hammerschmidt, J.; Nassaro, M.R.F.; Bauer, L.D.C.; Almeida, E.A.; Barreto, E.H.; Forte Maiolino Molento, C. Training the Environmental Military Police in the State of São Paulo for science-based assessment of animal mistreatment. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J. The assessment and implementation of animal welfare: Theory into practice. Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epizoot. 2005, 24, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorászkó, G. Kutyakötelesség, Útmutató a Felelős Kutyatartás Jogszabályi Előírásaihoz, 2nd ed.; Nemzeti Élelmiszerlánc-biztonsági Hivatal (NÉBIH): Budapest, Hungary, 2017; pp. 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Palais, J.M. Animal Cruelty Hurts People Too, How Animal Cruelty Crime Data Can Help Police Make Their Communities Safer for All, Police Chief Magazine, International Association of Chiefs of Police. Available online: https://www.policechiefmagazine.org/animal-cruelty-hurts-people-too/ (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Tracking Animal Cruelty FBI Collecting Data on Crimes Against Animals, FBI News. 2016. Available online: https://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/-tracking-animal-cruelty (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Basinska, B.A.; Wiciak, I.; Dåderman, A.M. Fatigue and burnout in police officers: The mediating role of emotions. Polic. Int. J. Police Strateg. Manag. 2014, 37, 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCraty, R.; Atkinson, M. Resilience training program reduces physiological and psychological stress in police officers. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2012, 1, 44–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Robinson, C.; Clausen, V. The Link Between Animal Cruelty and Human Violence, FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, United States Department of Justice. 2021. Available online: https://leb.fbi.gov/articles/featured-articles/the-link-between-animal-cruelty-and-human-violence (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- National Sheriffs’ Association. Animal Cruelty as a Gateway Crime, 1st ed.; Office of Community Oriented Policing Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- The Humane Society of the United States. Animal Cruelty and Human Violence FAQ. Available online: https://www.humanesociety.org/resources/animal-cruelty-and-human-violence-faq (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- PETA: Menschen, Die Tiere Quälen, Belassen es Selten Dabei. 2019. Available online: https://www.peta.de/themen/staatsanwalt/ (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Schultz, J.; Schönfelder, R.; Steidl, T. Gewalt gegen Tiere. Tierquallerei als Indiz für Gewalt gegen Menschen. Dtsch. Tierartzteblatt 2018, 66, 1636–1644. [Google Scholar]

- Palais, J.M. The Link between Animal Cruelty and Public Safety, PM Magazine. 2020. Available online: https://icma.org/articles/pm-magazine/link-between-animal-cruelty-and-public-safety (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Mariak, V. Die Spirale der Gewaltkriminalität IV/4., Neu Bearbeitete Auflage: Kriminologische Beiträge zur Prüfung der Verrohungsthese/Tierquälerei und Tiertötung als Vorstufe der Gewalt Gegen Menschen/COVID-19-Pandemie und Die Problematik Häuslicher Gewalt; Tredition GmbH: Hamburg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Scotland Yard CSI: The Link between Animal Abuse and #Murder, Twitter. 2017. Available online: https://mobile.twitter.com/ScotlandYardCSI/status/903739384016629760 (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Vaughn, M.G.; Fu, Q.; DeLisi, M.; Beaver, K.M.; Perron, B.E.; Terrell, K.; Howard, M.O. Correlates of cruelty to animals in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2009, 43, 1213–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Douglas, J.E.; Ressler, R.K.; Burgess, A.W.; Hartman, C.R. Criminal profiling from crime scene analysis. Behav. Sci. Law 1986, 4, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, R.; Touroo, R.; Olin, J.; Dolan, E. The influence of evidence on animal cruelty prosecution and case outcomes: Results of a survey. J. Forensic Sci. 2019, 64, 1687–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorászkó, G.; Rácz, B.; Gerencsér, F.; Ózsvári, L. The prosecutors’ experiences on court cases with animal cruelty in Hungary. Hung. Vet. J. 2021, 143, 165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Lorászkó, G.; Rácz, B.; Gerencsér, F.; Ózsvári, L. The experiences of the courts on cases with animal cruelty in Hungary. Hung. Vet. J. 2021, 143, 569–576. [Google Scholar]

- Sander, G.; Scandurra, A.; Kamenska, A.; MacNamara, C.; Kalpaki, C.; Bessa, C.F.; Laso, G.N.; Parisi, G.; Varley, L.; Wolny, M.; et al. Overview of harm reduction in prisons in seven European countries. Harm Reduct. J. 2016, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sunstein, C.R. Standing for Animals (with notes on animal rights). Ucla L. Rev. 1999, 47, 1333. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, N.; Signal, T. Lock’Em Up and Throw Away the Key: Community Opinions Regarding Current Animal Abuse Penalties. Aust. Anim. Prot. Law J. 2009, 3, 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sharman, K. Sentencing under our anti-cruelty statutes: Why our leniency will come back to bite us. Curr. Issues Crim. Justice 2002, 13, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, R.; Hebart, M.L.; Whittaker, A.L. Explaining the gap between the ambitious goals and practical reality of animal welfare law enforcement: A review of the enforcement gap in Australia. Animals 2020, 10, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Solodov, D. Crimes of animal cruelty in Poland: Case studies. Forensic Sci. Int. Anim. Environ. 2021, 1, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.K.; Sims, V.K.; Chin, M.G. Predictors of views about punishing animal abuse. Anthrozoös 2016, 29, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, V.K.; Chin, M.G.; Yordon, R.E. Don’t be cruel: Assessing beliefs about punishments for crimes against animals. Anthrozoös 2007, 20, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.; Hunstone, M.; Waerstad, J.; Foy, E.; Hobbins, T.; Wikner, B.; Wirrel, J. Human-to-Animal Similarity and Participant Mood Influence Punishment Recommendations for Animal Abusers. Soc. Anim. 2002, 10, 267–284. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, R.; Hebart, M.L.; Whittaker, A.L. Increasing Maximum Penalties for Animal Welfare Offences in South Australia—Has It Caused Penal Change? Animals 2018, 8, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hawes, S.M.; Hupe, T.; Morris, K.N. Punishment to support: The need to align animal control enforcement with the human social justice movement. Animals 2020, 10, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randour, M.L. Including animal cruelty as a risk factor in assessing risk and designing interventions. In Proceedings of the Persistent Safe Schools: The National Conference of the Hamilton Fish Institute on School and Community Violence, Washington, DC, USA, 27–29 October 2004. [Google Scholar]

| Associated Crimes | Often | Rarely | Exceptionally |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prohibited animal fights | 7 | 14 | 8 |

| Theft | 3 | 11 | 13 |

| Illegal gambling | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Firearms offences | 2 | 10 | 5 |

| Drug offences | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Assault and battery | 1 | 6 | 11 |

| Robbery | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Usury | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Prostitution | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Other crimes | 3 | 2 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lorászkó, G.; Vetter, S.; Rácz, B.; Sótonyi, P.; Ózsvári, L. Comparison of Police Data on Animal Cruelty and the Perception of Animal Welfare NGOs in Hungary. Animals 2023, 13, 1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13071224

Lorászkó G, Vetter S, Rácz B, Sótonyi P, Ózsvári L. Comparison of Police Data on Animal Cruelty and the Perception of Animal Welfare NGOs in Hungary. Animals. 2023; 13(7):1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13071224

Chicago/Turabian StyleLorászkó, Gábor, Szilvia Vetter, Bence Rácz, Péter Sótonyi, and László Ózsvári. 2023. "Comparison of Police Data on Animal Cruelty and the Perception of Animal Welfare NGOs in Hungary" Animals 13, no. 7: 1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13071224

APA StyleLorászkó, G., Vetter, S., Rácz, B., Sótonyi, P., & Ózsvári, L. (2023). Comparison of Police Data on Animal Cruelty and the Perception of Animal Welfare NGOs in Hungary. Animals, 13(7), 1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13071224