Simple Summary

Horses are highly social animals that preferably live in stable social groups and form long-term affiliative bonds. However, although their need for social interaction has not changed with domestication, domestic horses are often housed in individual stables with limited social contact with other horses or in group housing with regular changes in their group composition. Thus, this review aims to provide an overview of social ethograms to facilitate the inclusion of social behaviour in equine welfare assessment. A literature review yielded 27 papers that studied equine adult social behaviour using a well-defined ethogram. Social interactions were observed in 851 horses living in groups of 9.1 (mean +/− 6.8 s.d., range: 2–33) horses. A total of 40 (mean: 12.8/paper, range: 2–23) social behaviours were described, of which 60% (24/40) were agonistic, 30% (12/40) affiliative, 7.5% (3/40) investigative and 2.5% (1/40) neutral. The 27 papers focused predominantly on socio-negative interactions by including 67.7% agonistic and only 26% affiliative, 5.1% investigative and 1.2% neutral social behaviours in their research. The strong emphasis on agonistic behaviour contrasts sharply with the rarity of agonistic behaviour in stable horse groups and the well-established importance of affiliative interactions for equine welfare. Therefore, to advance the assessment of horses’ welfare, the ethogram needs to be refined to reflect the nuanced and complex equine social behaviour better and consider more affiliative and also ambivalent and socially tolerant interactions.

Abstract

Sociality is an ethological need of horses that remained unchanged by domestication. Accordingly, it is essential to include horses’ social behavioural requirements and the opportunity to establish stable affiliative bonds in equine management systems and welfare assessment. Thus, this systematic review aims to provide an up-to-date analysis of equine intraspecific social ethograms. A literature review yielded 27 papers that met the inclusion criteria by studying adult (≥2 years) equine social behaviour with conspecifics using a well-defined ethogram. Social interactions were observed in 851 horses: 320 (semi-)feral free-ranging, 62 enclosed (semi-)feral and 469 domesticated, living in groups averaging 9.1 (mean +/− 6.8 s.d., range: 2–33) horses. The ethograms detailed in these 27 studies included a total of 40 (mean: 12.8/paper, range: 2–23) social behaviours, of which 60% (24/40) were agonistic, 30% (12/40) affiliative, 7.5% (3/40) investigative and 2.5% (1/40) neutral. The 27 publications included 67.7% agonistic and only 26% affiliative, 5.1% investigative and 1.2% neutral social behaviours in their methodology, thus focusing predominantly on socio-negative interactions. The strong emphasis on agonistic behaviours in equine ethology starkly contrasts with the rare occurrence of agonistic behaviours in stable horse groups and the well-established importance of affiliative interactions for equine welfare. The nuanced and complex equine social behaviour requires refinement of the ethogram with a greater focus on affiliative, ambivalent and indifferent interactions and the role of social tolerance in equine social networks to advance equine welfare assessment.

1. Introduction

Horses are gregarious animals that, under naturalistic conditions, spend most of their time in close contact with conspecifics and live in social groups of typically five to six individuals [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Harem groups, consisting of one stallion and several mares with their juvenile offspring up to 2–3 years of age, usually have stable adult membership underpinned by long-term social bonds that are established and maintained by affiliative behaviours such as proximity or mutual grooming [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Horses show a marked preference for associating with particular individuals, their preferred partners, in their group, with familiarity and homophily counting among the most pervasive factors determining these reciprocal affiliative relationships [14,15,22,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Both male and female offspring disperse from their natal group around puberty [7,16,21,32,35]. Despite social dispersal, mares remain spatially philopatric and establish group fidelity to a new harem, typically in proximity to their natal group, at around 3–4 years of age [16]. Dispersed males join bachelor groups that are characterized by a fission-fusion structure [3,21,36,37,38,39]. Solitary horses are only rarely seen, as even displaced older stallions that have lost their harem tend to join bachelor groups [12].

Horses’ social organization is based on a stable, complex dominance hierarchy reflecting resource-holding potential, and a female defence polygyny [4,6,7,11,15,21,22,26,31,32,40]. Equine groups have overlapping home ranges and aggregate, forming multilevel societies (herds) with synchronized daily movement and seasonal migration and stable spatial and hierarchical positioning of the various groups within the herd [17,41]. The social complexity of maintaining long-term affiliative relationships and navigating multilevel societal structures requires the ability to recognize and remember individuals and their relative rank [17,42,43]. Indeed, horses are capable of cross-modal individual recognition using visual, auditory and olfactory cues even after a year’s absence and transitive inference of dominance relationships through observation [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. Horses’ social cognition is further demonstrated by third-party interventions in agonistic and affiliative dyadic interactions of group members and increased affiliative behaviour after a conflict [34,52,53]. As food-related aggression is not typically relevant in grazers that feed on widely dispersed and undefendable resources, agonistic interactions occur mainly to establish a dominance hierarchy and maintain personal space, in which horses only allow affiliative associates [13,14,39,54]. Dominance typically depends on age, physical characteristics, experience, and length of residency in the herd [13,14,39,55]. The stable composition and hierarchy of (semi-)feral equine groups and the long-term social bonds result in social cohesion and a low frequency of agonistic interactions, most (80%) of which are ritualized and do not involve physical contact [54,56].

Comparisons of the behaviour of feral and domesticated horses indicate that the species-specific social behaviour of horses has remained qualitatively relatively unchanged by domestication [13]; however, the environment of domestic horses has changed dramatically compared to naturalistic conditions. Although management systems that accommodate equine sociality exist, most domestic horses are confined to individual stables with limited contact with conspecifics [12,13,15,22,35,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. Lack of social contact is thought to be one of the most serious stressors for horses, as evidenced by significant increases in faecal corticosterone metabolites, and it triggers stress-related behaviours and stereotypies such as weaving, cribbing and box-walking in horses kept without adequate opportunities to socialize with conspecifics [12,54,56,58,60,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78]. Indeed, social contact, specifically the possibility to engage in affiliative behaviours such as allogrooming, which has been shown to lower the heart rate, has been identified as an ethological need and essential for equine welfare [15,22,56,79]. In addition to the limitation in social contact, managed horses also do not have the opportunity to choose their group affiliation. They are faced with frequent changes in group composition and social companionship, which limits their opportunities to establish long-term social bonds and a stable hierarchy, resulting in higher aggression and frequency of agonistic encounters [56,58,63,80]. The space restrictions inherent to domestic conditions, which limit the opportunities for subordinate individuals to escape or provide dominant conspecifics with their required individual distance, further compound the social challenge [56,58,62,80,81]. As horses do not adapt to repeated regrouping and a stable hierarchy is achieved only after 2–3 months [56,58], the common disregard of equine social group dynamics in equine husbandry poses a significant welfare concern [12,56,57,58,61,62,81].

Thus, it is essential to include horses’ social behavioural needs and the opportunity to establish stable affiliative bonds in equine management systems and welfare assessment [82]. However, to facilitate evidence-based optimization of equine husbandry practices and their evaluation, the influence of different environmental and management factors on equine social interactions needs to be further elucidated [83]. As differences in the sampled behaviours currently complicate the comparison of equine social behavioural studies, this systematic review aims to analyse the literature on equine social ethograms to distil a well-defined social behavioural repertoire as a basis for further studies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Searches

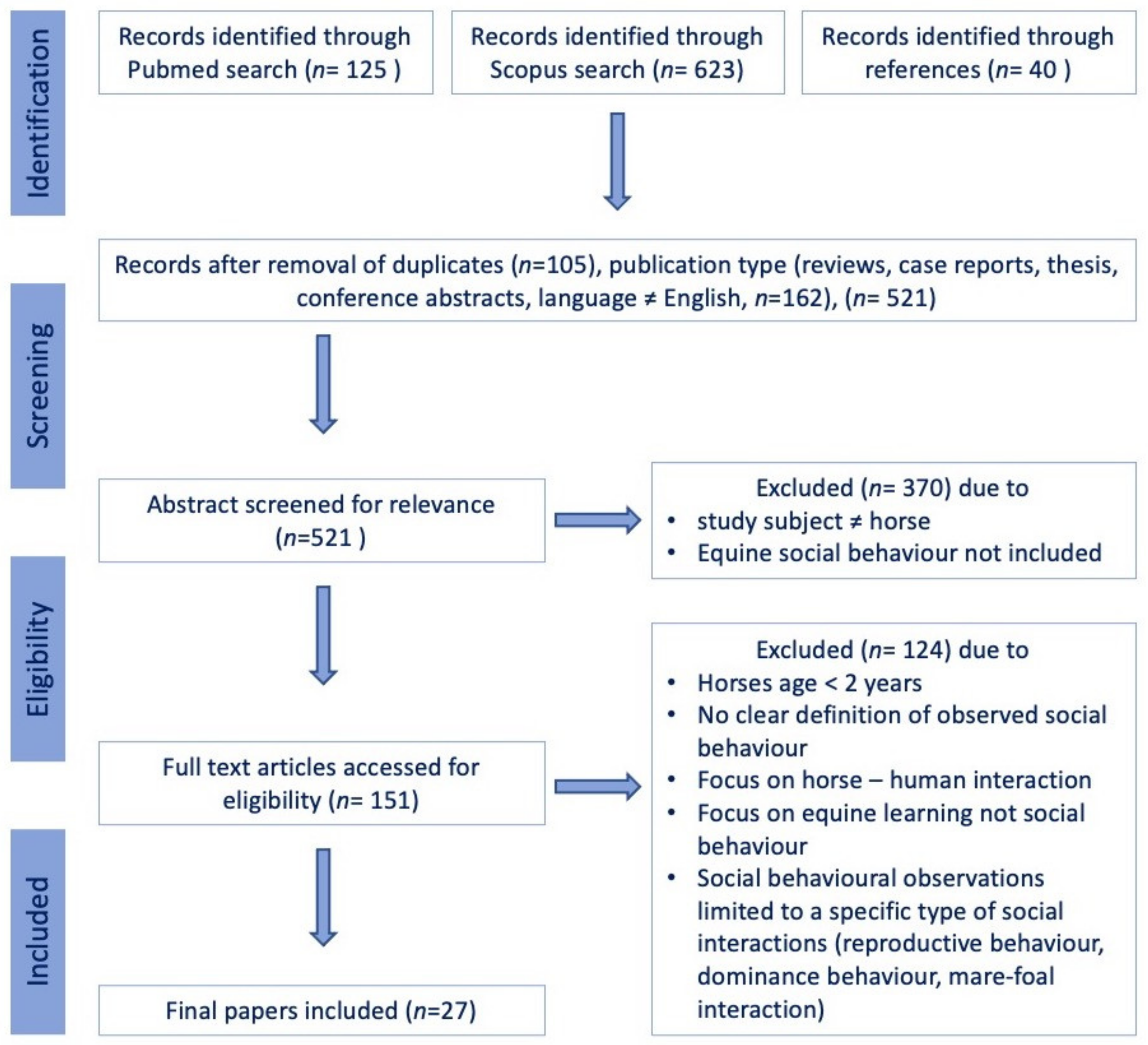

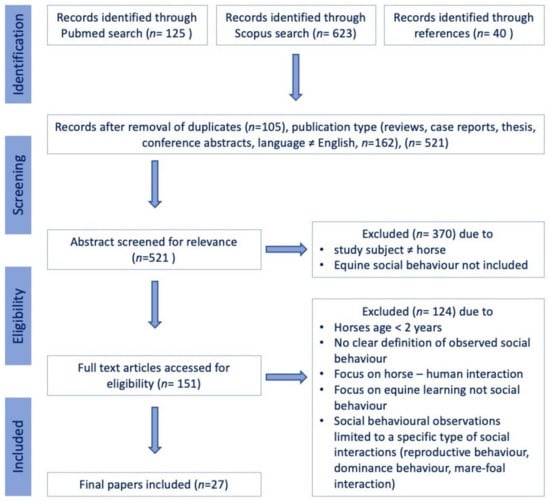

This review was carried out according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [84]. Scientific peer-reviewed articles focused on adult (≥2 years) equine intraspecific social behaviour were identified through a systematic search in the PubMed (National Institutes of Health. PubMed [Database]. Bethesda, MD, USA: National Library of Medicine; https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accessed on 25 January 2022) and Scopus (Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; https://www.scopus.com) electronic databases on 25 January 2022. The search was conducted by combining the search strings (“horse” OR “equine” OR “equus”) in the title and (“social” OR “ethogram” OR “agonistic” OR “affiliative”) in the title or abstract with the Boolean operator “AND”, with no restriction on publication date. The following exclusion criteria were set a priori (Figure 1): (a) non-peer-reviewed publication, dissertation, thesis, review, commentary, or single case report; (b) only a conference/seminar abstract published; (c) the article was not written in English; (d) the study did not include equine intraspecific social behaviour but focused on interspecies interaction or learning behaviour; (d) no ethogram of observed social behaviour was provided; (e) the observations were limited to a specific subset of behaviours (reproductive behaviour, dominance behaviour, mare-foal interaction); or (f) the observed horses were <2 years of age.

Figure 1.

Flow chart illustrating the study selection process for the systematic review.

2.2. Data Extraction and Risk of Bias Assessment

The study selection process was carried out by U.A. and F.J. following the procedure detailed in Figure 1. Any disagreement between the authors on the studies included in the review was resolved during a consensus meeting.

Information on the population, intervention, comparison, outcome and study design (PICOS) was retrieved from the articles, and the risk of bias in selected studies was assessed using a modification of the Evidence Project risk-of-bias tool [85,86,87].

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

A total of 125 articles were identified in PubMed, 623 additional papers in Scopus and another 40 based on references, yielding a total of 788 articles (Figure 1). After removing duplicates, reviews, commentaries, single case reports, books and non-English or German articles, 521 papers remained. Following the exclusion of papers that did not focus on adult (≥2 years) equine intraspecific social behaviour but on interspecies interaction or other behavioural observations or did not provide a well-defined ethogram of the observed behaviours, 27 articles remained and were included in the qualitative synthesis [5,12,13,14,22,26,27,29,30,34,37,41,52,54,55,56,58,62,79,80,88,89,90,91,92,93,94].

3.2. Quality and Risk of Bias Assessment

Of the 27 included papers, 22 (81.5% of the total) were ecological observational studies [5,12,14,22,26,27,30,34,37,41,52,54,55,56,62,79,88,89,90,91,92,93], and 5 (18.5%) prospective, non-blinded experimental studies, of which 3 had a pre-post [29,80,94] and 2 a randomized trial design [13,58]. Measurements of the dependent variables were conducted before and after a specific intervention, such as a change in paddock size [94], feeding tests [29] and a controlled change in a group composition [58].

Risk-of-bias assessment (Table 1) revealed the lack of a control group (only 7.4% of the articles fulfilled this criterion) [13,58], random assignment of participants to intervention (7.4% of the articles fulfilled this criterion) [13,58], a random selection of participants for assessment (none of the articles fulfilled this criterion), as the most critical concerns. Further limitations of some papers were caused by lacking control over confounding variables, such as changes in groups’ composition that were not controlled by the researchers [62,93] and specific interventions that were not part of the study design but may impact horses’ behaviour (e.g., mating of individuals during the study [29]; riding [94]).

Table 1.

List of the included articles, their study design, observation method(s) and the number of observation days.

The number of horses (6–145 horses/paper, mean: 31.5, +/− 32.5 s.d.), groups (1 to 18 groups, mean: 3.1, +/− 4 s.d.) and group size (2 to 33 individuals, mean: 9.1, +/− 6.8 s.d.) varied considerably between papers. The observation methods were restricted to direct manual observation in the field (27/27 papers, 100%), with additional manual behaviour scoring from video carried out in only 11.1% of the studies (3/27) [56,80,94]. No study used biotelemetry devices. The expression of specific social behaviours was assessed using four different methods: focal sampling in 18 (66.67%) papers [5,12,13,14,26,29,30,52,54,58,79,80,88,89,91,92,93,94]; ad libitum sampling in 6 (22.22%) papers [27,30,34,37,41,52]; all occurrence sampling in 4 (14.81%) papers [29,55,62,90]; and behaviour sampling in 1 (3.70%) [56]. In addition, scan sampling was applied in 59.26% (16/27 studies) to investigate spatial patterning [5,12,13,14,22,26,27,29,30,34,41,54,62,79,89,92].

Most studies (92.59%, 25/27) conducted their observations exclusively during the day (6:00–19:30) [5,13,14,26,27,29,30,34,37,41,52,54,56,58,62,79,80,88,89,90,91,92,93,94]; two (7.41%) included evening hours (up to 12 a.m.) [12,55], and only one observed the horses for the entire day (0–24 h) [22]. The observation time per group ranged from less than 6 h during an observation day in 59.26% (16/27) [12,13,14,29,30,52,54,55,58,79,80,88,89,90,91,94]; 6 to 12 h in 18.52% (5/27) [5,34,41,56,92]; and 24 h in 3.7% (1/27) [22]. The exact observation times were not provided in 14.81% (4/27) of the articles [27,30,37,93] and varied between 3 and 8 h a day for one article [62].

3.3. Data Synthesis

Six papers (22.2% of the total) studied free-ranging (≥300 ha) (semi-)feral horses [5,27,34,41,55,94]; six (22.2% of the total) (semi-)feral horses living in enclosures ranging from 2800 m2 to 75 ha [13,52,79,90,91,92]; and seventeen (58.6% of the total) domesticated horses [12,13,14,22,26,29,30,37,54,56,58,62,80,88,89,93,94] housed in paddocks or pastures ranging in size from 160 m2 to 17.2 ha. Two papers compared the behaviour of domesticated and semi-feral horses [13,93].

A total of 851 horses, aged 2–32 years, are included in the present systematic review (Table 2), of which 320 were free-ranging (semi-)feral horses, 62 enclosed (semi-)feral horses and 469 domesticated horses. The studies included, on average, 31.5 horses (+/− 32.5 s.d., range: 6–145) overall; 53.3 (+/− 53.9 s.d., range: 8–145) free-ranging (semi-feral) horses; 10.3 (+/− 3.8 s.d., range: 6–16) enclosed (semi-)feral horses; and 27.6 (+/− 22.7 s.d., range: 9–78) domesticated horses.

Table 2.

Signalment of the horses included in the study. Depending on the data available in the respective papers, ages are provided as range, median (plus range), or mean ± standard deviation. Similarly, the sex is detailed depending on the information provided in the papers.

The average number of groups per paper was 3.1 (+/− 4 s.d., range: 1–18) overall; 3.8 (+/− 3.65 s.d., range: 1–11) for free-ranging (semi-)feral horses; 1.2 (+/− 0.4 s.d., range: 1–2) for enclosed (semi-) feral horses; and 3.2 (+/− 4.5 s.d., range: 1–18) for domesticated horses. Group size averaged 9.1 horses/group (+/− 6.8 s.d., range: 2– 33) overall; 13.9 (+/− 8 s.d., range: 4–30) for free-ranging (semi-feral) horses; 8.9 (+/− 4.5 s.d., range: 4–16) for enclosed (semi-)feral horses; and 8.6 (+/− 7.2 s.d., range: 2–33) for domesticated horses.

The ethograms detailed 40 non-redundant intraspecific social behaviours (mean: 12.81/paper +/− 4.6 s.d., range. 2–23) (Table 3). Seven papers (25.93%) included less than ten different behaviours [5,27,29,80,88,91,93], thirteen papers (48.15%) between 10 and 15 different behaviours [12,13,14,22,26,30,34,41,52,56,62,89,94] and seven papers (25.93%) more than 15 behaviours [37,54,55,58,79,90,92]. The 40 social behaviours encompassed 24 agonistic interactions (60%), of which 19 were aggressive (47.5%) and 5 submissive (12.5%), but only 12 affiliative (30%), 3 investigative (7.5%) and one “neutral” behaviour (2.5%) (Table 3). Analysis of the application of the social ethogram revealed that the 27 papers detailed specific social behaviours as part of their methodology 331 times, of which 224 (67.7%) were agonistic, 86 (26%) affiliative, 17 (5.1%) investigative and 4 (1.2%) neutral behaviours, further confirming the focus on agonistic behaviours in equine ethology.

Table 3.

Ethograms of adult equine social behaviour used in the 27 papers.

The definitions of the social behaviours were similar between the different studies with only subtle differences between papers (e.g., “retreat” [27,34,37,41,52,80] and “avoidance” [14,22,26,30,37,62,90,92] were used interchangeably, “displacement” [54,62] was used to describe “supplantation” [29,79] and “agonistic approach eliciting retreat” [12,13,14,26,27,29,30,34,37,41,52,55,58,91,92]). Some papers limited the definitions of the ethograms to few words, making them more concise but also less precise and hence ambiguous [14,30,90], which can lead to confusion in the distinction of similar behaviours (e.g., “mild-threat” [14,30] and “head-threat” [5,29,37,62,79,90,94]) or behavioural patterns (e.g., “agonistic approach” [12,13,14,26,27,29,30,34,37,41,52,55,58,91,92] versus “displacement” [54,62] versus “supplantation” [29,79]).

In addition to the qualitative description of social behaviour, 22 papers (81.5%) also quantified social interactions (Table 4), including the frequency of behaviours and proximity events, the duration of interactions, ranking and dominance relationships [5,12,13,14,22,27,29,34,37,52,54,55,56,58,62,79,80,89,90,91,92,93,94]. Two articles included network analyses [41,52].

Table 4.

Quantitative assessments of social behaviour included in the 27 papers.

4. Discussion

Aiming to provide an up-to-date analysis of equine social ethograms, this systematic review included all original studies of equine social behaviour that detailed the ethogram underlying the reported research. Surprisingly, the equine social ethograms primarily reference the “agonistic ethogram of the equine bachelor band” (includes 23/40 behaviours, is referenced in 15/27 papers [12,13,22,27,34,37,41,52,54,56,58,80,92,93,94]), which was based on a literature review of equine behaviours and 50 daylight hours of observation of 15 pony stallions (2–21 years old) pastured together in a semi-natural enclosure of 9 acres [37]. While this landmark publication provides an excellent ethogram, it describes interactions in an equine bachelor group, which is neither under (semi-)feral nor domestic conditions the prevalent social group structure and hence may not suffice as a comprehensive behavioural catalogue for horses living in harems or human-managed groups. The strong focus on agonistic behaviours has persisted in equine ethology, with 67.7% of the social behaviours studied in the 27 papers focussing on the socio-negative spectrum and only 26% on affiliative, 5.1% on investigative and 1.2% on neutral behaviours. The rare occurrence of agonistic behaviours in stable horse groups (0.2–1.5 agonistic interactions/h per horse [13,56,79,95,96,97] and the well-established importance of affiliative interactions for equine welfare [12,15,22,31,54,56,58,60,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79] further emphasize the necessity to expand and diversify the equine social ethogram to include a broader spectrum of behaviours of horses living in different group compositions and environments.

The binary division in agonistic and affiliative social interactions as bipolar opposites belies the reality that many relationships are not one-dimensionally positive or negative but more multifaceted and may entail social tolerance, coactivated feelings of positivity and negativity toward a relational partner (ambivalence) or lack affective valence (indifference) [80,90,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108]. In human social sciences, the impact of ambivalent relationships on social networks and quality of life is increasingly recognized. Studies have shown them to be prevalent in both personal and professional networks and cause increased stress, blood pressure and detrimental health outcomes [98,109,110]. The social behaviour of horses similarly includes ambivalent interactions and relationships, such as the more frequent but less violent aggressive interactions among preferred associates and the predominant initiation of affiliative interactions by dominant individuals [5,22,26,29,30,56,80,90,107]. In addition, horses show social tolerance (defined as proximity to conspecifics around valuable resources with little or no aggression [108]) depending on space availability and their social experience [5,22,26,29,30,56,80,90,107]. As the current positive–negative dichotomy does not sufficiently reflect the nuanced and complex equine social behaviour, equine ethology can build upon the human social science approach of assessing the valence generated by social interactions along the continuum from negative to positive in combination with the elicited autonomic activation intensity (arousal) to refine equine ethograms [98,99,110,111,112,113,114].

The quantification of social interactions incorporated by 81.55% of the included papers also assists in assessing dyadic relationships and group dynamics. These quantitative criteria are primarily based on the reported interindividual distance of 2 m to two horse lengths, within which horses only tolerate close affiliates [12,13,27,38,39,54,115,116,117] and include measurements of spatial proximity between two horses, the number and duration of affiliative or agonistic interactions per hour and recording the nearest neighbour. In addition, recent studies have incorporated social network analysis to examine indirect connections beyond the dyad level and analyse the patterns of individual and group-level social interactions [41,52,118,119,120,121].

The combination of a more nuanced qualitative assessment of equine social behaviour with quantitative approaches may greatly assist equine welfare assessment and optimization, as poor welfare conditions, such as high population density (< 331 m2 per horse), may reduce equine sociality and skew horses’ social behavioural repertoire toward agonistic interactions [80,122,123]. Changes in social behaviour have also been associated with disease in various group-living species ranging from honeybees, zebrafish and mice to calves and humans [121,124,125,126,127], but the link between social networks and health has not yet been explored for horses. The changes seem species-specific, as mice reduce social interactions, while rhesus macaques and calves increase affiliative interactions with familiar conspecifics [121,128,129]. More detailed studies in sick humans found increased social interactions with familiar support figures but withdrawal from strangers and a strong correlation between pain intensity and interpersonal distance to strangers in patients with lower back pain [121,127,130,131]. Expanding social behavioural research in horses to also include assessment of the effect of acute and chronic disease on social interactions may further advance equine welfare by facilitating early detection, treatment and monitoring of disease and pain.

5. Conclusions

Horses, as social non-territorial equids that preferably live in stable, hierarchically structured social groups, have developed complex cognitive skills, ritualized communication signals and nuanced social behaviour. In these stable groups, the frequency of agonistic interactions is low under species-appropriate housing and welfare conditions (e.g., adequate enclosure size, stocking density and resource availability). However, our systematic review reveals a strong focus of current social ethograms on socio-negative interactions with 67.7% agonistic and only 26% affiliative, 5.1% investigative and 1.2% neutral social behaviours. The traditional equine ethology approach focusing on univalently negative social interactions does not sufficiently reflect the complexity of equine social behaviour and requires the development of a more refined ethogram, which also considers ambivalent and indifferent interactions and relationships and the role of social tolerance in equine social networks. A standardized comprehensive social ethogram combined with quantification of social interactions and social network analysis would facilitate research into the effect of disease and pain on equine social behaviour and constitute a valuable tool for equine welfare assessment and optimization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.J. and U.A.; methodology, F.J. and U.A.; data collection, F.J. and U.A.; data analysis, L.T.B. and F.J.; manuscript preparation F.J. and L.T.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Gut Aiderbichl and the Sandgrueb-Stiftung. Open Access Funding by the University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tyler, S.J. The behaviour and social organization of the New Forest ponies. Anim. Behav. Monogr. 1972, 5, 87–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collery, L. Observations of equine animals under farm and feral conditions. Equine Veter. J. 1974, 6, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feist, J.D.; McCullough, D.R. Behavior and communication patterns in feral horses. Z. Tierpsychol. 1976, 41, 337–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, R.E.; Hudson, R.J. Social organization of feral horses in western Canada. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 1982, 8, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, S.M.; von Goldschmidt-Rothschild, B. Social behaviour and relationships in a herd of Camargue horses. Z. Tierpsychol. 1979, 49, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaseda, Y.; Khalil, A.M.; Ogawa, H. Harem stability and reproductive success of Misaki feral mares. Equine Veter. J. 1995, 27, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaseda, Y.; Ogawa, H.; Khalil, A.M. Causes of natal dispersal and emigration and their effects on harem formation in Misaki feral horses. Equine Veter. J. 1997, 29, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glade, M.J. “Social sleeping” among confined horses. J. Equine Veter. Sci. 1986, 6, 156–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, J. Welfare lessons of equine social behaviour. Equine Veter. J. 1987, 19, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowell-Davis, S.L. Social behaviour of the horse and its consequences for domestic management. Equine Veter. Educ. 1993, 5, 148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linklater, W.; Cameron, E.; Stafford, K.; Veltman, C. Social and spatial structure and range use by Kaimanawa wild horses (Equus caballus: Equidae). N. Z. J. Ecol. 2000, 24, 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, J.W.; Ladewig, J.; Søndergaard, E.; Malmkvist, J. Effects of individual versus group stabling on social behaviour in domestic stallions. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2002, 75, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.W.; Zharkikh, T.; Ladewig, J.; Yasinetskaya, N. Social behaviour in stallion groups (Equus przewalskii and Equus caballus) kept under natural and domestic conditions. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2002, 76, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitor, F.; Oom, M.D.M.; Vicente, L. Social relationships in a herd of Sorraia horses: Part I. Correlates of social dominance and contexts of aggression. Behav. Process. 2006, 73, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dierendonck, M.C. The Importance of Social Relationships in Horses; Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Linklater, W.L.; Cameron, E.Z. Social dispersal but with philopatry reveals incest avoidance in a polygynous ungulate. Anim. Behav. 2009, 77, 1085–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, T.; Ochi, S.; Ringhofer, M.; Sosa, S.; Sueur, C.; Hirata, S.; Yamamoto, S. Aerial drone observations identified a multilevel society in feral horses. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonça, R.S.; Pinto, P.; Maeda, T.; Inoue, S.; Ringhofer, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Hirata, S. Population Characteristics of Feral Horses Impacted by Anthropogenic Factors and Their Management Implications. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 848741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J. Organizational systems and dominance in feral horses in the Grand Canyon. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1977, 2, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, C.R.; Mettke-Hofmann, C.; Hager, R.; Shultz, S. Social stability in semiferal ponies: Networks show interannual stability alongside seasonal flexibility. Anim. Behav. 2018, 136, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.R.; Schoenecker, K.A.; Cole, M.J. Effect of adult male sterilization on the behavior and social associations of a feral polygynous ungulate: The horse. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2022, 249, 105598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurjónsdóttir, H.; Snorrason, S.; van Dierendonck, M.; Thórhallsdóttir, A. Social relationships in a group of horses without a mature stallion. Behaviour 2003, 140, 783–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, E.Z.; Setsaas, T.H.; Linklater, W.L. Social bonds between unrelated females increase reproductive success in feral horses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 13850–13853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granquist, S.M.; Thorhallsdottir, A.G.; Sigurjonsdottir, H. The effect of stallions on social interactions in domestic and semi feral harems. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 141, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, R. Mutual grooming and preferred associate relationships in a band of free-ranging horses. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1998, 59, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitor, F.; Vicente, L. Affiliative relationships among Sorraia mares: Influence of age, dominance, kinship and reproductive state. J. Ethol. 2010, 28, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolter, R.; Stefanski, V.; Krueger, K. Parameters for the Analysis of Social Bonds in Horses. Animals 2018, 8, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouskila, A.; Lourie, E.; Sommer, S.; de Vries, H.; Hermans, Z.M.; van Dierendonck, M. Similarity in sex and reproductive state, but not relatedness, influence the strength of association in the social network of feral horses in the Blauwe Kamer Nature Reserve. Isr. J. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 61, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellard, M.-E.; Crowell-Davis, S.L. Evaluating equine dominance in draft mares. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1989, 24, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitor, F.; Oom, M.D.M.; Vicente, L. Social relationships in a herd of Sorraia horses: Part II. Factors affecting affiliative relationships and sexual behaviours. Behav. Process. 2006, 73, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, H.; Fragoso, S.; Heitor, F. The relevance of affiliative relationships in horses: Review and future directions. Pet Behav. Sci. 2019, 8, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, R.S.; Pinto, P.; Inoue, S.; Ringhofer, M.; Godinho, R.; Hirata, S. Social determinants of affiliation and cohesion in a population of feral horses. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 245, 105496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, M.; Suzuki, N. The contribution of mutual grooming to affiliative relationships in a feral misaki horse herd. Animals 2020, 10, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, G.; Krueger, K. Third-party interventions keep social partners from exchanging affiliative interactions with others. Anim. Behav. 2012, 83, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, E.; Søndergaard, E.; Keeling, L.J. Keeping horses in groups: A review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 136, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, D.; Wedekind, C.; Wespi, B.; Imboden, I.; Meinecke-Tillmann, S.; Sieme, H. The potential effects of social interactions on reproductive efficiency of stallions. J. Equine Veter. Sci. 2012, 32, 455–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, S.M.; Haviland, J.C.S. Agonistic ethogram of the equid bachelor band. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1995, 43, 147–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilson, R.L.; Sweeny, K.A.; Binczik, G.A.; Reindl, N.J. Buddies and bullies: Social structure of a bachelor group of Przewalski horses. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1988, 21, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitor, F.; Vicente, L. Dominance relationships and patterns of aggression in a bachelor group of Sorraia horses (Equus caballus). J. Ethol. 2010, 28, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, K.; Esch, L.; Farmer, K.; Marr, I. Basic Needs in Horses?—A Literature Review. Animals 2021, 11, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, K.; Flauger, B.; Farmer, K.; Hemelrijk, C. Movement initiation in groups of feral horses. Behav. Process. 2014, 103, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wascher, C.A.F.; Kulahci, I.G.; Langley, E.J.G.; Shaw, R.C. How does cognition shape social relationships? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 373, 20170293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, T.; Sueur, C.; Hirata, S.; Yamamoto, S. Behavioural synchronization in a multilevel society of feral horses. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proops, L.; McComb, K.; Reby, D. Cross-modal individual recognition in domestic horses (Equus caballus). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 947–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemasson, A.; Boutin, A.; Boivin, S.; Blois-Heulin, C.; Hausberger, M. Horse (Equus caballus) whinnies: A source of social information. Anim. Cogn. 2009, 12, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stomp, M.; Leroux, M.; Cellier, M.; Henry, S.; Lemasson, A.; Hausberger, M. An unexpected acoustic indicator of positive emotions in horses. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawroth, C.; Langbein, J.; Coulon, M.; Gabor, V.; Oesterwind, S.; Benz-Schwarzburg, J.; Von Borell, E. Farm animal cognition—Linking behavior, welfare and ethics. Front. Veter. Sci. 2019, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Péron, F.; Ward, R.; Burman, O. Horses (Equus caballus) discriminate body odour cues from conspecifics. Anim. Cogn. 2014, 17, 1007–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, K.; Flauger, B. Olfactory recognition of individual competitors by means of faeces in horse (Equus caballus). Anim. Cogn. 2011, 14, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, L.M.; Byrne, K.; D’eath, R.B. Pair-bonding and companion recognition in domestic donkeys, Equus asinus. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2013, 143, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, K.; Heinze, J. Horse sense: Social status of horses (Equus caballus) affects their likelihood of copying other horses’ behavior. Anim. Cogn. 2008, 11, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, K.; Schneider, G.; Flauger, B.; Heinze, J. Context-dependent third-party intervention in agonistic encounters of male Przewalski horses. Behav. Process. 2015, 121, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzi, A.; Sighieri, C.; Gazzano, A.; Nicol, C.J.; Baragli, P. Post-conflict friendly reunion in a permanent group of horses (Equus caballus). Behav. Process. 2010, 85, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, G.H.M.; Borsheim, L.; Mejdell, C.M.; Søndergaard, E.; Bøe, K.E. Grouping horses according to gender—Effects on aggression, spacing and injuries. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 120, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiper, R.; Receveur, H. Social interactions of free-ranging Przewalski horses in semi-reserves in the Netherlands. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1992, 33, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freymond, S.B.; Briefer, E.F.; Niederhäusern, R.V.; Bachmann, I. Pattern of social interactions after group integration: A possibility to keep stallions in group. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, E.; Christensen, J.W.; Keeling, L.J. Social interactions of unfamiliar horses during paired encounters: Effect of pre-exposure on aggression level and so risk of injury. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 121, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.W.; Søndergaard, E.; Thodberg, K.; Halekoh, U. Effects of repeated regrouping on horse behaviour and injuries. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 133, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanDierendonck, M.C.; Spruijt, B.M. Coping in groups of domestic horses—Review from a social and neurobiological perspective. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 138, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreevy, P.D.; Cripps, P.J.; French, N.P.; Green, L.E.; Nicol, C.J. Management factors associated with stereotypic and redirected behaviour in the thoroughbred horse. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1995, 44, 270–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourjade, M.; Moulinot, M.; Henry, S.; Richard-Yris, M.-A.; Hausberger, M. Could adults be used to improve social skills of young horses, Equus caballus? Dev. Psychobiol. 2008, 50, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierard, M.; McGreevy, P.; Geers, R. Effect of density and relative aggressiveness on agonistic and affiliative interactions in a newly formed group of horses. J. Veter. Behav. 2019, 29, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, V.E.; Arnott, G.; Turner, S.P. Social behavior in farm animals: Applying fundamental theory to improve animal welfare. Front. Veter. Sci. 2022, 9, 932217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarnell, K.; Hall, C.; Royle, C.; Walker, S.L. Domesticated horses differ in their behavioural and physiological responses to isolated and group housing. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 143, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Placci, M.; Marliani, G.; Sabioni, S.; Gabai, G.; Mondo, E.; Borghetti, P.; De Angelis, E.; Accorsi, P.A. Natural horse boarding vs. traditional stable: A comparison of hormonal, hematological and immunological parameters. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2020, 23, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marliani, G.; Sprocatti, I.; Schiavoni, G.; Bellodi, A.; Accorsi, P.A. Evaluation of horses’ daytime activity budget in a model of ethological stable: A case study in Italy. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2020, 24, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmucker, S.; Preisler, V.; Marr, I.; Krüger, K.; Stefanski, V. Single housing but not changes in group composition causes stress-related immunomodulations in horses. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAfee, L.M.; Mills, D.S.; Cooper, J.J. The use of mirrors for the control of stereotypic weaving behaviour in the stabled horse. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2002, 78, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søndergaard, E.; Jensen, M.B.; Nicol, C.J. Motivation for social contact in horses measured by operant conditioning. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 132, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, A.J.; Nicol, C.J.; French, N.P. Factors influencing the development of stereotypic and redirected behaviours in young horses: Findings of a four year prospective epidemiological study. Equine Veter. J. 2002, 34, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesimple, C.; Poissonnet, A.; Hausberger, M. How to keep your horse safe? An epidemiological study about management practices. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 181, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, K.; Schrott, A.; Kabai, P. Possible influence of neighbours on stereotypic behaviour in horses. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 111, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, C. Understanding equine stereotypies. Equine Vet. J. 1999, 31 (Suppl. S28), 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hothersall, B.; Casey, R. Undesired behaviour in horses: A review of their development, prevention, management and association with welfare. Equine Veter. Educ. 2012, 24, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heleski, C.R.; Shelle, A.C.; Nielsen, B.D.; Zanella, A.J. Influence of housing on weanling horse behavior and subsequent welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2002, 78, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, G.H.M.; Bøe, K.E. A note on the effect of daily exercise and paddock size on the behaviour of domestic horses (Equus caballus). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 107, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, G.H.M.; Liestøl, S.H.-O.; Bøe, K.E. Effects of enrichment items on activity and social interactions in domestic horses (Equus caballus). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 129, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, E.K.; Ellis, A.D.; Van Reenen, C.G. The effect of two different housing conditions on the welfare of young horses stabled for the first time. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 114, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feh, C. Social behaviour and relationships of Prezewalski horses in Dutch semi-reserves. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1988, 21, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flauger, B.; Krueger, K. Aggression level and enclosure size in horses (Equus caballus). Pferdeheilkunde Equine Med. 2013, 29, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raspa, F.; Tarantola, M.; Bergero, D.; Bellino, C.; Mastrazzo, C.M.; Visconti, A.; Valvassori, E.; Vervuert, I.; Valle, E. Stocking density affects welfare indicators in horses reared for meat production. Animals 2020, 10, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S.; Kemp, B. Social network analysis in farm animals: Sensor-based approaches. Animals 2021, 11, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, K.; Bryant, J.; Staley, M.; Whitham, J.; Miller, L. Behavioural diversity as a potential welfare indicator for professionally managed chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes): Exploring variations in calculating diversity using species-specific behaviours. Anim. Welf. 2021, 30, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, C.E.; Fonner, V.A.; Armstrong, K.A.; Denison, J.A.; Yeh, P.T.; O’reilly, K.R.; Sweat, M.D. The Evidence Project risk of bias tool: Assessing study rigor for both randomized and non-randomized intervention studies. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafaina-Domínguez, B.; Collado-Mateo, D.; Merellano-Navarro, E.; Villafaina, S. Effects of dog-based animal-assisted interventions in prison population: A systematic review. Animals 2020, 10, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, G.W.; Grassia, A. Ethogram of agonistic behaviour for thoroughbred horses. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 1982, 8, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood-Gush, D.G.M.; Galbraith, F. Social relationships in a herd of 11 geldings and two female ponies. Equine Veter. J. 1987, 19, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolter, L.; Zimmermann, W. Social behaviour of Przewalski horses (Equus p. przewalskii) in the Cologne Zoo and its consequences for management and housing. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1988, 21, 117–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiper, R.R. Social interactions of the Przewalski horse (Equus przewalskii Poliakov, 1881) herd at the Munich Zoo. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1988, 21, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharkikh, T.L.; Andersen, L. Behaviour of bachelor males of the Przewalski horse (Equus ferus przewalskii) at the reserve Askania Nova. Der Zoöl. Gart. 2009, 78, 282–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górecka-Bruzda, A.; Fureix, C.; Ouvrard, A.; Bourjade, M.; Hausberger, M. Investigating determinants of yawning in the domestic (Equus caballus) and Przewalski (Equus ferus przewalskii) horses. Sci. Nat. 2016, 103, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majecka, K.; Klawe, A. Influence of paddock size on social relationships in domestic horses. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2017, 21, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fureix, C.; Bourjade, M.; Henry, S.; Sankey, C.; Hausberger, M. Exploring aggression regulation in managed groups of horses Equus caballus. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 138, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurjónsdóttir, H.; Haraldsson, H. Significance of Group Composition for the Welfare of Pastured Horses. Animals 2019, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourjade, M.; Tatin, L.; King, S.R.B.; Feh, C. Early reproductive success, preceding bachelor ranks and their behavioural correlates in young Przewalski’s stallions. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 2009, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methot, J.R.; Melwani, S.; Rothman, N.B. The space between us: A social-functional emotions view of ambivalent and indifferent workplace relationships. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1789–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briefer, E.F.; Maigrot, A.-L.; Mandel, R.; Freymond, S.B.; Bachmann, I.; Hillmann, E. Segregation of information about emotional arousal and valence in horse whinnies. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, T.D.; Butterworth, P. Supportive, aversive, ambivalent, and indifferent partner evaluations in midlife and young-old adulthood. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2010, 65, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fureix, C.; Jego, P.; Henry, S.; Lansade, L.; Hausberger, M. Towards an ethological animal model of depression? A study on horses. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, R.G.; Uchino, B.N.; Cribbet, M.R.; Bowen, K.; Smith, T.W. Social relationships and sleep quality. Ann. Behav. Med. 2015, 49, 912–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchino, B.N.; Holt-Lunstad, J.; Uno, D.; Flinders, J.B. Heterogeneity in the social networks of young and older adults: Prediction of mental health and cardiovascular reactivity during acute stress. J. Behav. Med. 2001, 24, 361–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Uchino, B.N.; Smith, T.W.; Olson-Cerny, C.; Nealey-Moore, J.B. Social relationships and ambulatory blood pressure: Structural and qualitative predictors of cardiovascular function during everyday social interactions. Health Psychol. 2003, 22, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhaoyang, R.; Sliwinski, M.J.; Martire, L.M.; Smyth, J.M. Social interactions and physical symptoms in daily life: Quality matters for older adults, quantity matters for younger adults. Psychol. Health 2019, 34, 867–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasper, K.; Spencer, L.A.; Hu, D. Does neutral affect exist? How challenging three beliefs about neutral affect can advance affective research. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linklater, W.L.; Cameron, E.Z. Tests for cooperative behaviour between stallions. Anim. Behav. 2000, 60, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.A.; van Leeuwen, E.J.; Whiten, A. Chimpanzees’ behavioral flexibility, social tolerance, and use of tool-composites in a progressively challenging foraging problem. iScience 2021, 24, 102033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Uchino, B.N. Social ambivalence and disease (SAD): A theoretical model aimed at understanding the health implications of ambivalent relationships. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 14, 941–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestelmeyer, P.E.G.; Kotz, S.A.; Belin, P. Effects of emotional valence and arousal on the voice perception network. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2017, 12, 1351–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.; Randle, H.; Pearson, G.; Preshaw, L.; Waran, N. Assessing equine emotional state. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 205, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, L.; Holkenborg, S.K.; Reimert, I.; Bolhuis, J.E.; Webb, L.E. The nuts and bolts of animal emotion. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 113, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.V.; Proops, L.; Grounds, K.; Wathan, J.; Scott, S.K.; McComb, K. Domestic horses (Equus caballus) discriminate between negative and positive human nonverbal vocalisations. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briefer, E.F.; Mandel, R.; Maigrot, A.L.; Freymond, S.B.; Bachmann, I.; Hillmann, E. Perception of emotional valence in horse whinnies. Front. Zool. 2017, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N.; Randle, H. Personal space requirements of mares versus geldings (Equus caballus): Welfare implications and visual representation of spatial data via Spatial Web diagrams). BSAP Occas. Publ. 2006, 35, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.V. Measuring social behavior: Social dominance. J. Anim. Sci. 1986, 62, 1120–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, J.W.; Crowell-Davis, S.L.; Caudle, A.B.; Heusner, G.L. Aggression and social spacing in light horse (Equus caballus) mares and foals. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2000, 68, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, S.; Yamamoto, S.; Ringhofer, M.; Mendonça, R.S.; Pereira, C.; Hirata, S. Spatial positioning of individuals in a group of feral horses: A case study using drone technology. Mammal Res. 2019, 64, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salau, J.; Hildebrandt, F.; Czycholl, I.; Krieter, J. “HerdGPS-Preprocessor”—A Tool to Preprocess Herd Animal GPS Data; Applied to Evaluate Contact Structures in Loose-Housing Horses. Animals 2020, 10, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, F.; Büttner, K.; Salau, J.; Krieter, J.; Czycholl, I. Proximity between horses in large groups in an open stable system—Analysis of spatial and temporal proximity definitions. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 242, 105418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, K.C.; Nascimento-Emond, S.D.; Hixson, C.L.; Miller-Cushon, E.K. Social networks respond to a disease challenge in calves. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhajali, H.; Richard-Yris, M.A.; Leroux, M.; Ezzaouia, M.; Charfi, F.; Hausberger, M. A note on the time budget and social behaviour of densely housed horses: A case study in Arab breeding mares. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 112, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevez, I.; Andersen, I.-L.; Nævdal, E. Group size, density and social dynamics in farm animals. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 103, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockmaier, S.; Bolnick, D.I.; Page, R.A.; Carter, G.G. An immune challenge reduces social grooming in vampire bats. Anim. Behav. 2018, 140, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazlauskas, N.; Klappenbach, M.; Depino, A.M.; Locatelli, F.F. Sickness behavior in honey bees. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsten, K.; Soares, S.M.; Koakoski, G.; Kreutz, L.C.; Barcellos, L.J.G. Characterization of sickness behavior in zebrafish. Brain Behav. Immun. 2018, 73, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.-M.; Wu, B.; Chen, C.-C.; Wang, J.; Peng, M.-S.; Zhang, Z.-J.; Wang, X.-Q. Association of Chronic Low Back Pain with Personal Space Regulation. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 719271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, P.C.; Block, P.; König, B. Infection-induced behavioural changes reduce connectivity and the potential for disease spread in wild mice contact networks. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willette, A.A.; Lubach, G.R.; Coe, C.L. Environmental context differentially affects behavioral, leukocyte, cortisol, and interleukin-6 responses to low doses of endotoxin in the rhesus monkey. Brain Behav. Immun. 2007, 21, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, N.I.; Inagaki, T.K.; Mashal, N.M.; Irwin, M.R. Inflammation and social experience: An inflammatory challenge induces feelings of social disconnection in addition to depressed mood. Brain Behav. Immun. 2010, 24, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, T.K.; Muscatell, K.A.; Irwin, M.R.; Moieni, M.; Dutcher, J.M.; Jevtic, I.; Breen, E.C.; Eisenberger, N.I. The role of the ventral striatum in inflammatory-induced approach toward support figures. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 44, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).