Simple Summary

Fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-23 is a phosphaturic hormone. The information regarding reference intervals (RIs) of FGF-23 in cats is limited. We aimed to establish RIs in a large cohort of clinically healthy cats and to investigate correlations with sex and age. A total of 118 cats with unremarkable complete blood count and serum chemistry profiles were included. RIs were calculated using the reference interval advisor software 2.1 (Microsoft Excel). The RI for FGF-23 concentrations spanned 85.8 to 387.0 pg/mL (90% confidence interval: lower limit 40.5 to 103.9 pg/mL, upper limit: 354.6 to 425.0 pg/mL). No significant relationships (r2 = 0.044) were detected with age (p = 0.081) or sex (p = 0.191). Other studies of the same diagnostic assay calculated RIs of 56 to 700 pg/mL in 79 cats and <336 pg/mL in 108 cats, and concordance with the present study did not detect any correlation with sex or age.

Abstract

Fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-23 is a phosphaturic hormone. An association between increasing FGF-23 levels and progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) was documented in cats, dogs, and humans. The information regarding reference intervals (RIs) of FGF-23 in cats is limited. We aimed to establish RIs in a large cohort of clinically healthy cats and to investigate correlations with sex and age. A total of 118 cats with unremarkable complete blood count and serum chemistry profile were included. Clinically sick cats, cats with concurrent diseases, suspicion of CKD, or receiving renal diets were excluded. FGF-23 concentrations were measured with the FGF-23 ELISA Kit. RIs were calculated using the reference interval advisor software 2.1 (Microsoft Excel). FGF-23 concentrations were correlated with sex and age. The RI for FGF-23 concentrations spanned 85.8 to 387.0 pg/mL (90% confidence interval: lower limit 40.5 to 103.9 pg/mL, upper limit: 354.6 to 425.0 pg/mL). No significant relationships (r2 = 0.044) were detected with age (p = 0.081) or sex (p = 0.191). Other studies of the same diagnostic assay calculated RIs of 56 to 700 pg/mL in 79 cats and <336 pg/mL in 108 cats, and in concordance with the present study, did not detect any correlation with sex or age.

1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is one of the most common diseases in cats with an overall prevalence of 2 to 4% [1,2]. In cats over 10 years of age, the prevalence can be as high as 30 to 40% [3,4]. The prognosis correlates with the CKD stage as defined by the International Renal Interest Society (IRIS). Staging is based on such parameters as serum creatinine concentration, blood pressure measurements, and urine protein/creatinine ratio [5]. The modified IRIS guidelines also include concentration of serum symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) as a marker for glomerular filtration rate (GFR) [6]. Moreover, Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF)-23 has also recently been added to the IRIS guidelines as a marker for deranged metabolism.

FGF-23 is a phosphaturic hormone produced by osteocytes and osteoblasts. It is responsible for the homeostasis of phosphorus and calcitriol [7,8]. FGF-23 regulates serum phosphate levels by increasing the excretion of renal phosphate and decreasing the synthesis and degradation of calcitriol. An increase in FGF-23 concentration promotes urinary excretion of phosphorus and decreases its absorption in the intestines [9,10,11]. In addition, FGF-23 also acts on the parathyroid gland and reduces both the synthesis and secretion of the parathyroid hormone [12]. In humans suffering from CKD, serum FGF-23 concentration rises exponentially as renal function declines, far preceding any significant increase in serum phosphate or parathyroid hormone concentrations [12,13,14]. Additionally, FGF-23 concentration negatively correlates with the estimated GFR in humans [14]. Hyperphosphatemia and increased calcitriol concentration in blood both stimulate FGF-23 production.

So far, several studies have indicated FGF-23 as a promising early parameter for phosphate derangement in feline CKD [15,16,17,18]. FGF-23 might also have diagnostic relevance for the early detection of both CKD and phosphate derangement in cats with CKD. Disruption of phosphate homeostasis may develop in the early stages of CKD, preceding azotemia or hyperphosphatemia. FGF-23 concentration is significantly higher in cats with azotemic CKD when compared to healthy animals and increases significantly with the progression of CKD [15,16]. However, the true diagnostic potential of FGF-23 in cats remains largely unknown.

Regarding the use of available FGF-23 assays in cats, several studies have been performed. The following diagnostic quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits have been tested: the FGF-23 ELISA kit (Kainos Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan) by four studies [15,17,19,20], the MyBioSource ELISA (MyBioSource, San Diego, CA, USA) by two studies [16,21], and the MedFrontier FGF23 ELISA (Minaris Medical Co., Tokyo, Japan) by another study [22]. In a study from 2023 performed by the same authors, where the FGF-23 ELISA kit, the MyBioSource ELISA, and the LIAISON FGF 23 kit for intact FGF-23 were all compared on the Liaison platform developed by DiaSorin (Saluggia, Italy), the FGF-23 ELISA kit (Kainos Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan) demonstrated the best correlation with various creatinine concentrations according to the IRIS [23]. The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation (CVs) of this assay were all below 15%, thus indicating a reliable performance [23].

Nevertheless, all current knowledge regarding reference intervals (RIs) for the FGF-23 ELISA kit is derived from only two studies, providing the following RIs of 56 to 700 pg/mL in 79 cats [15] and 0 to 366 pg/mL in 108 cats [20]. Therefore, the aim of this study was (1) to establish RIs for FGF-23 in a large cohort of clinically healthy cats and (2) to investigate correlations of FGF-23 concentration with sex and age in clinically healthy, non-azotemic cats.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

The submitting veterinarians were asked to provide information on the general health status of the individual cats at the time of blood collection, any concurrent acute as well as chronic diseases, including suspicion for CKD, and administration of renal diet. This data was collected by questionnaires and telephone calls. Inclusion criteria for the cats were: classified as clinically healthy by the treating veterinarian, no known acute or chronic diseases, no present clinical signs typical of CKD, and not receiving any specific renal diet.

2.2. Sample Collection

Serum samples used in this study were leftover volumes from the send-in routine diagnostic samples of the clinical laboratory LABOKLIN (Bad Kissingen, Germany) from December 2022. Only cats with unremarkable Complete Blood Count (CBC) results performed by the Sysmex XN-V analyzer (Sysmex Deutschland, Norderstedt, Germany) on EDTA blood, as well as unremarkable biochemistry profile findings performed by Cobas 8000 (Roche, Mannheim, Germany: alanine transaminase, albumin, alkaline phosphatase, alpha-amylase, bilirubin, calcium, cholesterol, creatine kinase, DGGR-lipase, fructosamine, globulin, glucose, glutamate dehydrogenase, magnesium, creatinine, SDMA, phosphorus, potassium, sodium, total protein, triglycerides, and urea) on the serum samples according to the reference intervals of the laboratory were included in this study. Only cats with creatinine concentration of <140 µmol/L (1.6 mg/dL) and SDMA concentration of <18 µg/dL were included, which corresponds to the IRIS stage 1. Hematological and the above-mentioned biochemical parameters were evaluated immediately after an overnight shipment to the laboratory. Meanwhile, for the FGF-23 measurements, the serum samples were stored frozen for a maximum of 5 working days at −20 °C.

2.3. Analytic Methods

FGF-23 concentration was measured in serum with the FGF-23 ELISA Kit (Kainos Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. According to the manufacturer’s specifications, the minimum detection limit for the Kainos ELISA assay was 3 pg/mL, while the quantification range spanned 3–800 pg/mL. In the LABOKLIN laboratory, coefficients of variation of <15% are considered to indicate a good performance of the chosen diagnostic assay in cats [23]. In detail, the intra-assay precision in the LABOKLIN laboratory showed coefficients of variation of 12.54%, 4.17%, and 4.19%, while inter-assay precision values were 9.2%, 9.96%, and 8.17% for samples with low, moderate, and high FGF-23 levels, respectively [23].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Age and sex were analyzed descriptively. Statistical analysis was completed using SPSS for Windows (version 29.0; SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA). The Anderson–Darling test was used to check for normality. Reference intervals for FGF-23 were calculated nonparametrically according to the ASVCP reference interval guidelines [24] using the reference interval advisor software 2.1 on Microsoft Excel for Microsoft Windows 365 [25] and comprised the central 95% of the fitted distribution with 90% confidence intervals calculated around the lower (2.5%) and upper (97.5%) limits using the bootstrap method. Prior transformation of the reference data was done and Horn’s algorithm using Tukey’s interquartile fences were used for identification of potential outliers. A multiple linear regression model of FGF-23 concentrations was fitted with age and sex as cofactors. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used for comparison of FGF-23 levels regarding sex and age. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

The age and sex were known in all 118 cats included in this study. Regarding age, a median age of 9 years was calculated (mean 8.81 years, standard deviation 4.36 years, minimum 1 year, maximum 20 years). Regarding sex, 55/118 cats were male (46.6%, intact 10/55 cats [18.2%], castrated 45/55 cats [81.8%]) and 63 females (53.4%, intact 14/63 cats [22.2%], spayed 49/63 cats [77.8%]).

3.2. FGF-23 Concentrations

The serum FGF-concentrations were not normally distributed (Anderson–Darling testing: p = 0.004) in this population of 118 cats and ranged from 40.5 to 425.0 pg/mL (mean: 210.2 pg/mL, median 204.8 pg/mL, standard deviation 77.8 pg/mL).

In female cats, FGF-23 showed a median of 210.2 pg/mL (mean 219.9 pg/mL, standard deviation 79.9 pg/mL, minimum 40.5 pg/mL, maximum 425.0 pg/mL). A median of 179.6 pg/mL was demonstrated in males (mean 199.1 pg/mL, standard deviation 74.4 pg/mL, minimum 86.2 pg/mL, maximum 398.7 pg/mL). No statistically significant differences in FGF-23 levels were demonstrated comparing male to female cats (p = 0.102).

The study group was divided into cats < 9 years (n = 52) and cats ≥ 9 years (n = 66) according to the median of 9 years in the cats included in the study. In cats < 9 years, FGF-23 levels showed a median of 177.8 pg/mL (mean 194.3 pg/mL, standard deviation 80.4 pg/mL, minimum 40.5 pg/mL, maximum 386.7 pg/mL) compared to a median of 212.6 pg/mL (mean 222.7 pg/mL, standard deviation 73.8 pg/mL, minimum 99.6 pg/mL, maximum 425.0 pg/mL) in cats ≥ 9 years. There was a statistically significant impact of age on FGF-23 levels (p = 0.025).

3.3. FGF-23 Reference Interval

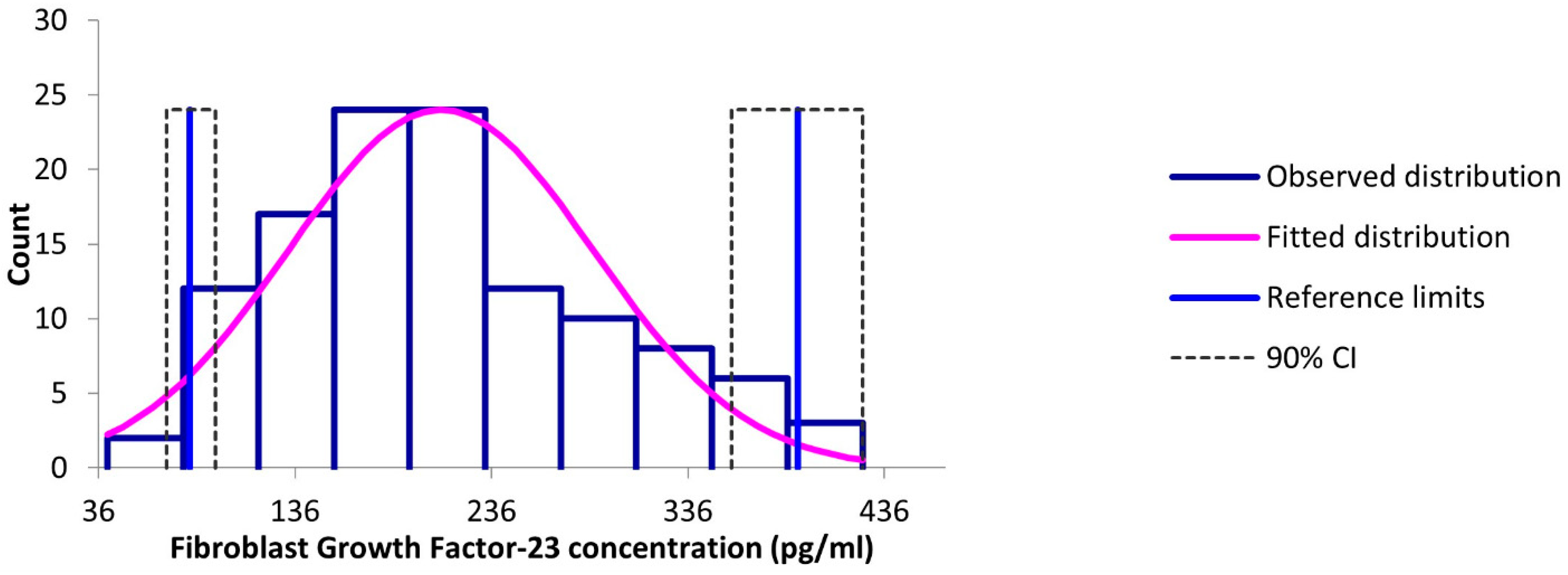

No outliers were identified by the Tukey method. The RI for FGF-23 concentrations spanned between 85.8 and 387.0 pg/mL with a 90% confidence interval of 40.5 to 103.9 pg/mL for the lower limits and 354.6 to 425.0 pg/mL for the upper limits (Figure 1). A generalized linear model did not detect any significant correlation (r2 = 0.044) between serum FGF-23 concentrations and age (p = 0.081) or sex (p = 0.191).

Figure 1.

Distribution of Fibroblast Growth Factor-23 concentrations in 118 clinically healthy cats.

4. Discussion

The FGF-23 ELISA Kit (Kainos Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan) demonstrated the best diagnostic performance in a study by the same authors in 2023 when three different FGF-23 assays were compared in cats [23]. Although originally developed to detect human FGF-23, this assay was soon successfully applied in cats as well [15,17,23]. The knowledge regarding RIs for this FGF-23 ELISA kit is currently based on two studies demonstrating RIs of 56 to 700 pg/mL in 79 cats [15] and 0 to 366 pg/mL in 108 cats [20]. The calculated RI in our study (85.8 to 387.0 pg/mL) is in concordance with the second study, especially regarding the upper limit. Regarding the FGF-23 measurements, it must also be mentioned that assay- and species-specific RI seem to be important. Thus, the study comparing three different diagnostic FGF-23 assays revealed a high variation of FGF-23 concentrations in cats depending on the assay used [23]. Meanwhile, in a study performed by the same authors in clinically healthy dogs (n = 136) with the same FGF-23 assay, a RI of 95.8 (90% confidence interval: 44.6–139.2 pg/mL) to 695.1 pg/mL (90% confidence interval: 598.7–799.1 pg/mL) was established and was thus much wider than the RI currently established in cats [26]. Moreover, the upper RI in 115 clinically healthy pediatric human subjects was 61.2 pg/mL (90% confidence interval: 58.6–63.7 pg/mL) [27] using the LIAISON FGF 23 kit for intact FGF-23 on the Liaison platform developed by DiaSorin (Saluggia, Italy), further emphasizing the importance of species-specific and assay-related RIs.

The storage of a maximum of five days while frozen most likely did not influence the FGF-23 concentrations in the samples of our study, as FGF-23 has been documented to show no significant changes in samples stored for various periods at different temperatures in earlier studies [28,29]. The general guidelines of the laboratory recommend taking blood samples after overnight fasting to exclude the influence of feeding, especially on biochemistry parameters.

FGF-23 is a useful biomarker for the identification and better understanding of CKD–mineral and bone disorder [30]. Further studies in cats are needed to evaluate the outcome of an early dietary invention in cats with increased FGF-23 levels. The value of FGF-23 in the identification and prediction of CKD progression has to be further evaluated [30].

Regarding age, a statistically significant difference in FGF-23 concentrations was noted with clinically healthy dogs aged < 9 years to dogs 9 years of age or older with a trend for increasing FGF-23 concentrations with age [26]; it was also seen in cats in our study as well as in a previous study [17]. However, no significant correlation of FGF-23 concentrations with age or sex was demonstrated. In a study with clinically healthy geriatric cats, FGF-23 concentrations of up to 700 pg/mL were detected [15], which was not seen in our study. However, in the 11 cats aged 15 years and older in this study, a median FGF-concentration of 253.1 pg/mL was noted (mean 236.3 pg/mL, standard deviation 56.5 pg/mL, minimum 104.0 pg/mL, maximum 313.8 pg/mL), which was higher than the results of the whole population altogether (mean: 210.2 pg/mL, median 204.8 pg/mL, standard deviation 77.8 pg/mL). Further studies with larger cohorts and a higher number of clinically healthy geriatric cats are recommended.

Limitations

For cats included in calculations for RIs, health status was based both on the results of questionnaires to the veterinarians and on unremarkable hematological and biochemical findings. Potentially important background information was unavailable to the authors, including living conditions and reasons for blood sampling and laboratory testing. Therefore, no data regarding history, clinical signs, blood pressure measurement, urinalysis, diagnostic imaging, and prior or current medications were included in the study. The application of phosphate binders could also not be ruled out with certainty. Due to the missing urinalysis, the measurement of the specific urinary gravity in the cats included in the study and substaging using the urinary protein-to-creatinine-ratio to rule out proteinuria as recommended by the IRIS guidelines [6] was not possible. Therefore, any tubular dysfunction may have been missed, potentially influencing the FGF-23 production by renal tubules in the cats included in the study.

5. Conclusions

An RI for FGF-23 concentrations of 85.8 to 387.0 pg/mL with a 90% confidence interval of 40.5 to 103.9 pg/mL for the lower limits and 354.6 to 425.0 pg/mL for the upper limits was established in a population of 118 clinically healthy cats. This is in accordance with other studies that have calculated the RIs to be 56 to 700 pg/mL and 0 to 336 pg/mL. The latter study detected no statistical impact of sex and age on FGF-23 concentrations, which agreed with our study. Larger study cohorts of clinically healthy cats are further recommended.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and I.S.; methodology, S.L., S.F.M., E.M., J.v.L. and I.S.; software, I.S.; validation, I.S. and E.M.; formal analysis, I.S.; investigation, N.N.; resources, N.N. and S.F.M.; data curation, S.L., N.N. and I.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, N.N., S.F.M., E.M., J.v.L. and I.S.; visualization, I.S.; supervision, S.F.M., E.M., J.v.L. and I.S.; project administration, S.L., S.F.M., J.v.L. and I.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to the use of leftover volumes from the send-in routine diagnostic samples of the clinical laboratory LABOKLIN (Bad Kissingen, Germany).

Informed Consent Statement

The informed consent has been obtained from each owner of each individual cats participating in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Parts of this study were presented as an oral presentation at the congress of the German Association of Veterinary Medicine (DVG) in Berlin from 22–25 September 2023.

Conflicts of Interest

E.M. is the CEO of the commercial laboratory LABOKLIN (Bad Kissingen, Germany). N.N., S.F.M., J.v.L., S.L., and I.S. are employees of the laboratory. This has not influenced the results of this study in any way. There are no relevant financial and non-financial competing interests to report.

References

- Lund, E.M.; Armstrong, P.J.; Kirk, C.A.; Kolar, L.M.; Klausner, J.S. Health status and population characteristics of dogs and cats examined at private veterinary practices in the United States. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1999, 214, 1336–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, D.G.; Church, D.B.; McGreevy, P.D.; Thomson, P.C.; Brodbelt, D.C. Prevalence of disorders recorded in cats attending primary-care veterinary practices in England. Vet. J. 2014, 202, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepson, R.E.; Brodbelt, D.; Vallance, C.; Syme, H.M.; Elliott, J. Evaluation of predictors of the development of azotemia in cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2009, 23, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, C.L.; Lascelles, B.D.; Vaden, S.L.; Gruen, M.E.; Marks, S.L. Prevalence and classification of chronic kidney disease in cats randomly selected from four age groups and in cats recruited for degenerative joint disease studies. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2014, 16, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkes, A.H.; Caney, S.; Chalhoub, S.; Elliott, J.; Finch, N.; Gajanayake, I.; Langston, C.; Lefebvre, H.P.; White, J.; Quimby, J. ISFM consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of feline chronic kidney disease. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2016, 18, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renal Interest Society (IRIS). IRIS Staging of CKD (Modified in 2023). Available online: http://iris-kidney.com/pdf/2_IRIS_Staging_of_CKD_2023.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Liu, S.; Guo, R.; Simpson, L.G.; Xiao, Z.S.; Burnham, C.E.; Quarles, L.D. Regulation of fibroblastic growth factor 23 expression but not degradation by PHEX. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 37419–37426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.C.; Juppner, H.; Azucena-Serrano, C.E.; Yadin, O.; Salusky, I.B.; Wesseling-Perry, K. Patterns of FGF-23, DMP1, and MEPE expression in patients with chronic kidney disease. Bone 2009, 45, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, T.; Hasegawa, H.; Yamazaki, Y.; Muto, T.; Hino, R.; Takeuchi, Y.; Fujita, T.; Nakahara, K.; Fukumoto, S.; Yamashita, T. FGF-23 is a potent regulator of vitamin D metabolism and phosphate homeostasis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2004, 19, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, H.; Maeda, A.; Ohtomo, S.; Hirata, M.; Kusano, K.; Kato, S.; Ogata, E.; Segawa, H.; Miyamoto, K.; Fukushima, N. Circulating FGF-23 is regulated by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and phosphorus in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 2543–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Quarles, L.D. How fibroblast growth factor 23 works. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 18, 1637–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitta, K.; Nagano, N.; Tsuchiya, K. Fibroblast growth factor 23/klotho axis in chronic kidney disease. Nephron Clin. Pract. 2014, 128, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isakova, T.; Wahl, P.; Vargas, G.S.; Gutierrez, O.M.; Scialla, J.; Xie, H.; Appleby, D.; Nessel, L.; Bellovich, K.; Chen, J.; et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 is elevated before parathyroid hormone and phosphate in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2011, 79, 1370–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ix, J.H.; Shlipak, M.G.; Wassel, C.L.; Whooley, M.A. Fibroblast growth factor-23 and early decrements in kidney function: The Heart and Soul Study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2010, 25, 993–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddes, R.F.; Finch, N.C.; Elliott, J.; Syme, H.M. Fibroblast growth factor 23 in feline chronic kidney disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2013, 27, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.L.; Chou, C.C.; Lee, Y.J. The association of indoxyl sulfate with fibroblast growth factor-23 in cats with chronic kidney disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2019, 33, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, N.C.; Geddes, R.F.; Syme, H.M.; Elliott, J. Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23) concentrations in cats with early nonazotemic chronic kidney disease (CKD) and in healthy geriatric cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2013, 27, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, H.J.; Jepson, R.E.; Chang, Y.M.; Biourge, V.C.; Bijsmans, E.S.; Elliott, J. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and symmetric dimethylarginine concentrations in geriatric cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2019, 33, 2657–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddes, R.F.; Elliott, J.; Syme, H.M. Relationship between plasma fibroblast growth Factor-23 concentration and survival time in cats with chronic kidney disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2015, 29, 1494–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Lin, L.; Chen, S.; Yu, L.; Chen, S.; Xia, Z. Serum fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23): Associations with hyperphosphatemia and clinical staging of feline chronic kidney disease. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2021, 33, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grelova, S.; Karasova, M.; Tothova, C.; Kiskova, T.; Baranova, D.; Lukac, B.; Fialkovicova, M.; Michalova, A.; Kunay, L.; Svoboda, M. Relationship between FGF 23, SDMA, urea, creatinine and phosphate in relation to feline chronic kidney disease. Animals 2022, 12, 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyakawa, H.; Hsu, H.H.; Ogawa, M.; Miyagawa, Y.; Takemura, N. Assessment of the measurement of canine and feline serum fibroblast growth factor-23 concentrations by automated chemiluminescence immunoassay. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 84, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapsina, S.; Nagler, N.; Müller, S.F.; Holtdirk, A.; Kottmann, T.; Müller, E.; von Luckner, J.; Schäfer, I. Comparison of three different diagnostic assays for Fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23) measurements in cats: A pilot study. Animals 2023, 13, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrichs, K.R.; Harr, K.E.; Freeman, K.P.; Szladovits, B.; Walton, R.M.; Barnhart, K.F.; Blanco-Chavez, J.; American Society for Veterinary Clinical Pathology. ASVCP reference interval guidelines: Determination of de novo reference intervals in veterinary species and other related topics. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2012, 41, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geffre, A.; Concordet, D.; Braun, J.P.; Trumel, C. Reference Value Advisor: A new freeware set of macroinstructions to calculate reference intervals with Microsoft Excel. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2011, 40, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapsina, S.; Nagler, N.; Müller, S.F.; Holtdirk, A.; Kottmann, T.; Müller, E.; Schäfer, I. Fibroblast Growth Factor-23 (FGF-23) in dogs-Reference interval and correlation with hematological and biochemical parameters. Animals 2023, 13, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brescia, V.; Fontana, A.; Lovero, R.; Capobianco, C.; Marsico, S.V.; De Chirico, T.; Pinto, C.; Varraso, L.; Cazzolla, A.P.; Di Serio, F. Determination of iFGF23 upper reference limits (URL) in healthy pediatric population, for its better correct use. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1018523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Maouche, D.; Dumitrescu, C.E.; Andreopoulou, P.; Gafni, R.I.; Brillante, B.A.; Bhattacharyya, N.; Fedarko, N.S.; Collins, M.T. Stability and degradation of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23): The effect of time and temperature and assay type. Osteoporos. Int. 2016, 27, 2345–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Lu, Y.; Yin, R.; Zhu, P.; Zhu, L.; Zheng, C. The effects of storage time and repeated freeze-thaw cycles on Intact Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 levels. Biopreserv. Biobank. 2021, 19, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, S.; Michael, H.T.; Szlosek, D.; Mack, R. Blood fibroblast growth factor 23 concentration in cats with and without chronic kidney disease: A scoping review. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2024, 26, 1098612X241234984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).