Communication in Dogs

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

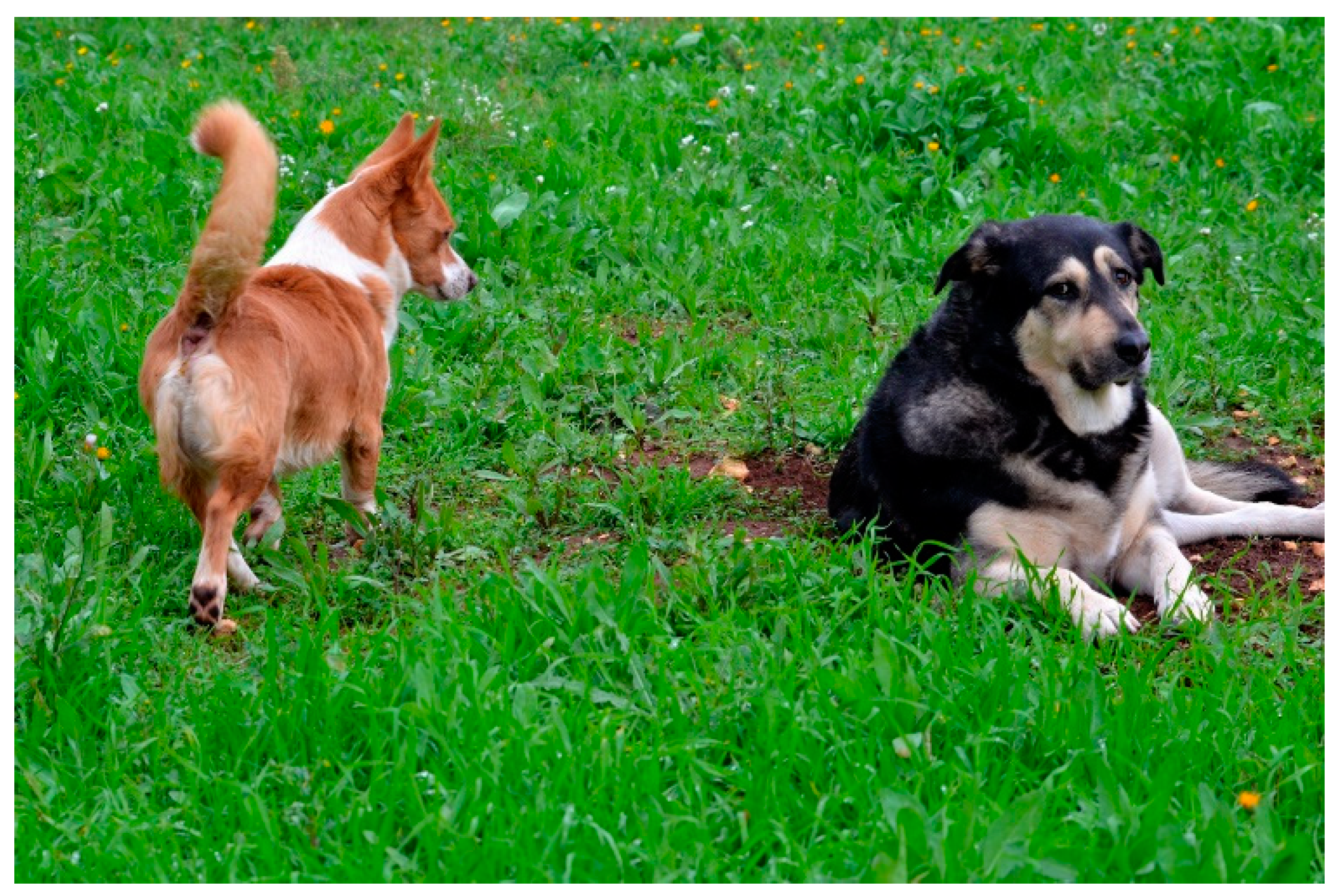

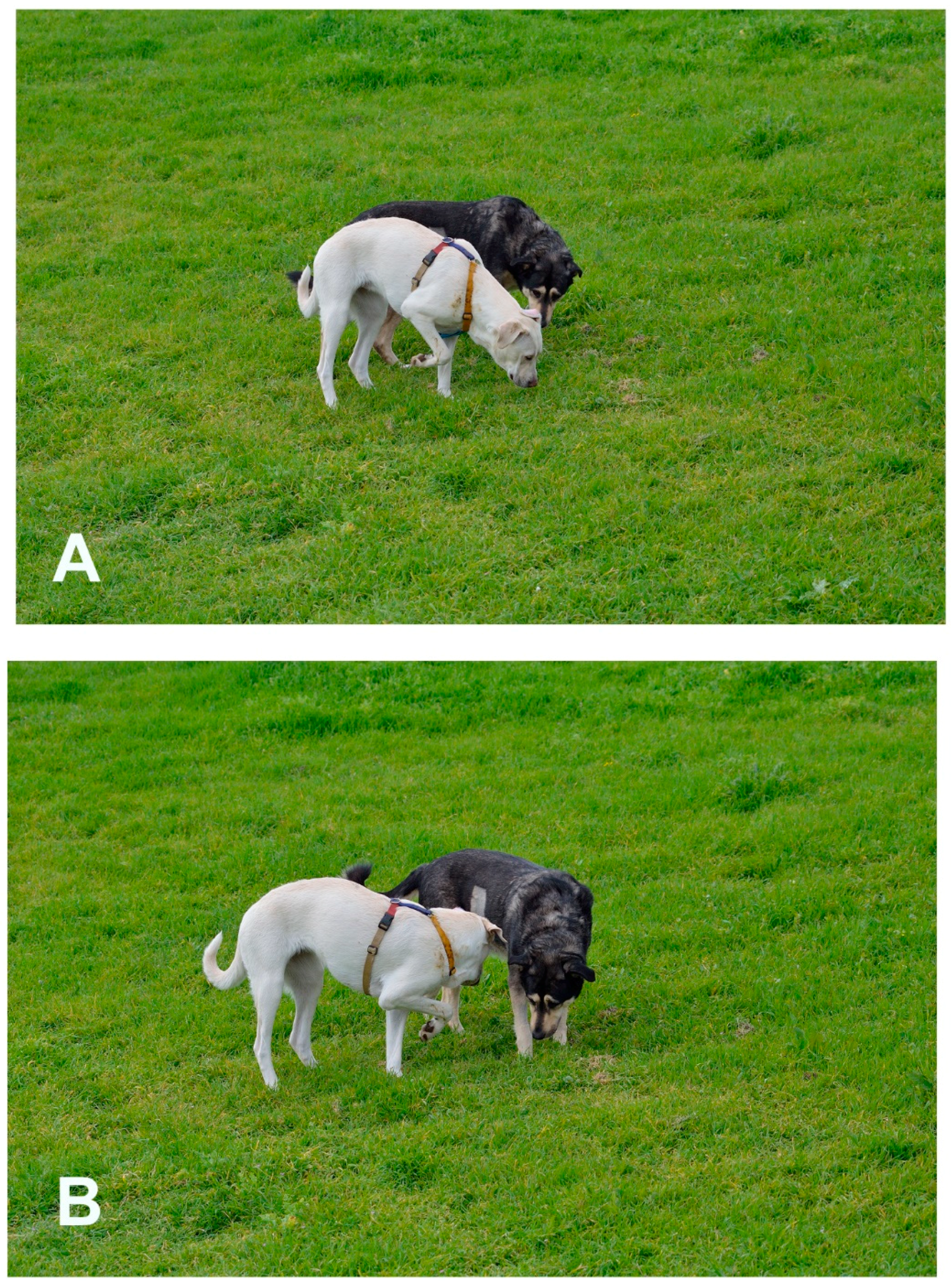

2. Visual Communication

3. Acoustic Communication

4. Olfactory Communication

5. Tactile Communication

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elgier, A.M.; Jakovcevic, A.; Barrera, G.; Mustaca, A.E.; Bentosela, M. Communication between domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) and humans: Dogs are good learners. Behav. Process. 2009, 81, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thalmann, O.; Shapiro, B.; Cui, P.; Schuenemann, V.J.; Sawyer, S.K.; Greenfield, D.L.; Germonpré, M.B.; Sablin, M.V.; López-Giráldez, F.; Domingo-Roura, X.; et al. Complete mitochondrial genomes of ancient canids suggest a European origin of domestic dogs. Science 2013, 342, 871–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminski, J.; Nitzschner, M. Do dogs get the point? A review of dog–human communication ability. Learn. Motiv. 2013, 44, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topàl, J.; Miklòsi, Á.; Csànyi, V.; Dòka, A. Attachment behaviour in dogs (Canis familiaris): A new application of Ainsworth’s (1969) Strange Situation Test. J. Comp. Psychol. 1998, 112, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siniscalchi, M.; Stipo, C.; Quaranta, A. “Like Owner, Like Dog”: Correlation between the Owner’s Attachment Profile and the Owner-Dog Bond. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worsley, H.K.; O’Hara, S.J. Cross-species referential signalling events in domestic dogs (Canis familiaris). Anim. Cogn. 2018, 21, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topál, J.; Kis, A.; Oláh, K. Dogs’ sensitivity to human ostensive cues: A unique adaptation? In The Social Dog, 1st ed.; Kaminski, J., Marshall-Pescini, S., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; p. 329. ISBN 9780124078185. [Google Scholar]

- Handelman, B. Canine Behavior: A Photo Illustrated Handbook; Dogwise Publishing: Wenatchee, WA, USA, 2012; ISBN 0976511827. [Google Scholar]

- Siniscalchi, M.; d’Ingeo, S.; Quaranta, A. The dog nose “KNOWS” fear: Asymmetric nostril use during sniffing at canine and human emotional stimuli. Behav. Brain Res. 2016, 304, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, J.W.; Rooney, N. Dog social behavior and communication. In The Domestic Dog; Serpell, J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 133–159. ISBN 978-0521425377. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht, J.; Horowitz, A. Introduction to dog behaviour. In Animal Behaviour for Shelter Veterinarians and Staff, 1st ed.; Weiss, E., Mohan-Gibbons, H., Zawistowski, S., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: London, UK, 2015; pp. 5–30. ISBN 978-1118711118. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, D.L. Behaviour of Dogs. In The Ethology of Domestic Animals: An Introductory Text, 3rd ed.; Jensen, P., Ed.; CABI: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 228–238. ISBN 9781786391650. [Google Scholar]

- Buxton, D.F.; Goodman, D.C. Motor function and the corticospinal tracts in the dog and raccoon. J. Comp. Neurol. 1967, 129, 341–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, R.J. Well-being and affective style: Neural substrates and biobehavioural correlates. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 2004, 359, 1395–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siniscalchi, M.; Lusito, R.; Vallortigara, G.; Quaranta, A. Seeing left-or right-asymmetric tail wagging produces different emotional responses in dogs. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 2279–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminski, J.; Hynds, J.; Morris, P.; Waller, B.M. Human attention affects facial expressions in domestic dogs. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Somppi, S.; Törnqvist, H.; Hänninen, L.; Krause, C.M.; Vainio, O. How dogs scan familiar and inverted faces: An eye movement study. Anim. Cogn. 2014, 17, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somppi, S.; Törnqvist, H.; Kujala, M.V.; Hänninen, L.; Krause, C.M.; Vainio, O. Dogs evaluate threatening facial expressions by their biological validity–Evidence from gazing patterns. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0143047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasparson, A.A.; Badridze, J.; Maximov, V.V. Colour cues proved to be more informative for dogs than brightness. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 20131356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siniscalchi, M.; d’Ingeo, S.; Fornelli, S.; Quaranta, A. Are dogs red–green colour blind? R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017, 4, 170869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beerda, B.; Schilder, M.B.H.; van Hoff, J.A.R.A.M.; de Vries, H.W. Manifestations of chronic and acute stress in dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1997, 52, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnetta, B.; Hare, B.; Tomasello, M. Cues to food location that domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) of different ages do and do not use. Anim. Cogn. 2000, 3, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, J.; Schumann, K.; Kaminski, J.; Call, J.; Tomasello, M. The early ontogeny of human–dog communication. Anim. Behav. 2008, 75, 1003–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, L.J.; Range, F.; Müller, C.A.; Serisier, S.; Huber, L.; Virányi, Z. Training for eye contact modulates gaze following in dogs. Anim. Behav. 2015, 106, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miklósi, Á.; Soproni, K. A comparative analysis of animals’ understanding of the human pointing gesture. Anim. Cogn. 2006, 9, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soproni, K.; Miklósi, Á.; Topal, J.; Csanyi, V. Comprehension of human communicative signs in pet dogs (Canis familiaris). J. Comp. Psychol. 2001, 115, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udell, M.A.R.; Giglio, R.F.; Wynne, C.D.L. Domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) use human gestures but not nonhuman tokens to find hidden food. J. Comp. Psychol. 2008, 122, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Aniello, B.; Scandurra, A.; Alterisio, A.; Valsecchi, P.; Prato-Previde, E. The importance of gestural communication: A study of human–dog communication using incongruent information. Anim. Cogn. 2016, 19, 1231–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminski, J.; Schulz, L.; Tomasello, M. How dogs know when communication is intended for them. Dev. Sci. 2012, 15, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miklósi, Á.; Topál, J. What does it take to become ‘best friends’? Evolutionary changes in canine social competence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2013, 17, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Téglás, E.; Gergely, A.; Kupán, K.; Miklósi, Á.; Topál, J. Dogs’ gaze following is tuned to human communicative signals. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virányi, Z.; Gácsi, M.; Kubinyi, E.; Topál, J.; Belényi, B.; Ujfalussy, D.; Miklósi, Á. Comprehension of human pointing gestures in young human-reared wolves (Canis lupus) and dogs (Canis familiaris). Anim. Cogn. 2008, 11, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miklósi, Á.; Polgárdi, R.; Topál, J.; Csányi, V. Intentional behaviour in dog–human communication: An experimental analysis of ‘showing’ behaviour in the dog. Anim. Cogn. 2000, 3, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gácsi, M.; Miklósi, Á.; Varga, O.; Topál, J.; Csányi, V. Are readers of our face readers of our minds? Dogs (Canis familiaris) show situation-dependent recognition of human’s attention. Anim. Cogn. 2004, 7, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vas, J.; Topál, J.; Gácsi, M.; Miklósi, Á.; Csányi, V. A friend or an enemy? Dogs’ reaction to an unfamiliar person showing behavioural cues of threat and friendliness at different times. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 94, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, H.E.; Young, L.J. Oxytocin and the neural mechanisms regulating social cognition and affiliative behavior. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2009, 30, 534–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nagasawa, M.; Mitsui, S.; En, S.; Ohtani, N.; Ohta, M.; Sakuma, Y.; Onaka, T.; Mogi, K.; Kikusui, T. Oxytocin-gaze positive loop and the coevolution of human-dog bonds. Science 2015, 348, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab, C.; Huber, L. Obey or not obey? Dogs (Canis familiaris) behave differently in response to attentional states of their owners. J. Comp. Psychol. 2006, 120, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminski, J.; Neumann, M.; Bräuer, J.; Call, J.; Tomasello, M. Dogs, Canis familiaris, communicate with humans to request but not to inform. Anim. Behav. 2011, 82, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunet, F.; Deputte, B.L. Functionally referential and intentional communication in the domestic dog: Effects of spatial and social contexts. Anim. Cogn. 2011, 14, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miklósi, Á.; Kubinyi, E.; Topál, J.; Gácsi, M.; Virányi, Z.; Csányi, V. A simple reason for a big difference: Wolves do not look back at humans but dogs do. Curr. Biol. 2003, 13, 763–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savalli, C.; Resende, B.; Gaunet, F. Eye contact is crucial for referential communication in pet dogs. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaunet, F. How do guide dogs and pet dogs (Canis familiaris) ask their owners for their toy and for playing? Anim. Cogn. 2010, 13, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgier, A.M.; Jakovcevic, A.; Mustaca, A.E.; Bentosela, M. Learning and owner–stranger effects on interspecific communication in domestic dogs (Canis familiaris). Behav. Proc. 2009, 81, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duranton, C.; Gaunet, F. Behavioral synchronization and affiliation: Dogs exhibit human-like skills. Learn. Behav. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duranton, C.; Bedossa, T.; Gaunet, F. Pet dogs synchronize their walking pace with that of their owners in open outdoor areas. Anim. Cogn. 2018, 21, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duranton, C.; Bedossa, T.; Gaunet, F. Interspecific behavioural synchronization: Dogs present locomotor synchrony with humans. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duranton, C.; Bedossa, T.; Gaunet, F. When facing an unfamiliarperson, pet dogs present social referencing based on their owner’s direction of movement alone. Anim. Behav. 2016, 113, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duranton, C.; Gaunet, F. Behavioural synchronization from an ethological perspective: Short overview of its adaptive values. Adapt. Behav. 2016, 24, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törnqvist, H.; Somppi, S.; Koskela, A.; Krause, C.M.; Vainio, O.; Kujala, M.V. Comparison of dogs and humans in visual scanning of social interaction. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2015, 2, 150341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bloom, T.; Friedman, H. Classifying dogs’ (Canis familiaris) facial expressions from photographs. Behav. Proc. 2013, 96, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, C.A.; Schmitt, K.; Barber, A.L.; Huber, L. Dogs can discriminate emotional expressions of human faces. Curr. Biol. 2015, 25, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merola, I.; Prato-Previde, E.; Marshall-Pescini, S. Dogs’ social referencing towards owners and strangers. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merola, I.; Prato-Previde, E.; Lazzaroni, M.; Marshall-Pescini, S. Dogs’ comprehension of referential emotional expressions: Familiar people and familiar emotions are easier. Anim. Cogn. 2014, 17, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuquerque, N.; Guo, K.; Wilkinson, A.; Resende, B.; Mills, D.S. Mouth-licking by dogs as a response to emotional stimuli. Behav. Process. 2018, 146, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siniscalchi, M.; Quaranta, A.; Rogers, L.J. Hemispheric specialization in dogs for processing different acoustic stimuli. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siniscalchi, M.; d’Ingeo, S.; Quaranta, A. Orienting asymmetries and physiological reactivity in dogs’ response to human emotional faces. Learn. Behav. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeon, S.C. The vocal communication of canines. J. Vet. Behav. 2007, 2, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongrácz, P.; Molnár, C.; Miklósi, Á. Barking in family dogs: An ethological approach. Vet. J. 2010, 183, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feddersen-Petersen, D.U. Vocalization of European wolves (Canis lupus lupus L.) and various dog breeds (Canis lupus f. fam.). Arch. Tierz. 2000, 43, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoleva, S.S.; Volodin, J.A.; Volodina, E.V.; Trut, L.N. To bark or not to bark:vocalizations by red foxes selected for tameness or aggressiveness toward humans. Bioacoustics 2012, 18, 99–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.M.; Reby, D.; McComb, K. Context-related variation in the vocal growling behaviour of the domestic dog (Canis familiaris). Ethology 2009, 115, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongrácz, P.; Molnár, C.S.; Miklósi, Á.; Csányi, V. Human listeners are able to classify dog (Canis familiaris) barks recorded in different situations. J. Comp. Psychol. 2005, 119, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faragó, T.; Pongrácz, P.; Range, F.; Virányi, Z.; Miklósi, Á. ‘The bone is mine’: Affective and referential aspects of dog growls. Anim. Behav. 2010, 79, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, C.S.; Kaplan, F.; Roy, P.; Pachet, F.; Pongrácz, P.; Dóka, A.; Miklósi, Á. Classification of dog barks: A machine learning approach. Anim. Cogn. 2008, 11, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, S.; McCowan, B. Barking in domestic dogs: Context specificity and individual identification. Anim. Behav. 2004, 68, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongrácz, P.; Szabó, É.; Kis, A.; Péter, A.; Miklósi, Á. More than noise?—Field investigations of intraspecific acoustic communication in dogs (Canis familiaris). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 159, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, C.; Pongrácz, P.; Faragó, T.; Dóka, A.; Miklósi, Á. Dogs discriminate between barks: The effect of context and identity of the caller. Behav. Process. 2009, 82, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faragó, T.; Pongrácz, P.; Miklósi, Á.; Huber, L.; Virányi, Z.; Range, F. Dogs’ expectation about signalers’ body size by virtue of their growls. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuquerque, N.; Guo, K.; Wilkinson, A.; Savalli, C.; Otta, E.; Mills, D. Dogs recognize dog and human emotions. Biol. Lett. 2016, 12, 20150883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Siniscalchi, M.; Lusito, R.; Sasso, R.; Quaranta, A. Are temporal features crucial acoustic cues in dog vocal recognition? Anim. Cogn. 2012, 15, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andics, A.; Miklósi, Á. Neural processes of vocal social perception: Dog-human comparative fMRI studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 85, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminski, J.; Call, J.; Fischer, J. Word learning in a domestic dog: Evidence for “fast mapping”. Science 2004, 304, 1682–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colbert-White, E.N.; Tullis, A.; Andresen, D.R.; Parker, K.M.; Patterson, K.E. Can dogs use vocal intonation as a social referencing cue in an object choice task? Anim. Cogn. 2018, 21, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersson, H.; Kaminski, J.; Herrmann, E.; Tomasello, M. Understanding of human communicative motives in domestic dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 133, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rooney, N.J.; Bradshaw, J.W.; Robinson, I.H. Do dogs respond to play signals given by humans? Anim. Behav. 2001, 61, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siniscalchi, M.; d’Ingeo, S.; Fornelli, S.; Quaranta, A. Lateralized behavior and cardiac activity of dogs in response to human emotional vocalizations. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gruber, T.; Grandjean, D. A comparative neurological approach to emotional expressions in primate vocalizations. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 73, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pongrácz, P.; Molnár, C.; Miklósi, Á. Acoustic parameters of dog barks carry emotional information for humans. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2006, 100, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faragó, T.; Takács, N.; Miklósi, Á.; Pongrácz, P. Dog growls express various contextual and affective content for human listeners. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017, 4, 170134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Taylor, A.M.; Reby, D.; McComb, K. Human listeners attend to size information in domestic dog growls. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2008, 123, 2903–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A.M.; Reby, D.; McComb, K. Why do large dogs sound more aggressive to human listeners: Acoustic bases of motivational misattributions. Ethology 2010, 116, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faragó, T.; Andics, A.; Devecseri, V.; Kis, A.; Gácsi, M.; Miklósi, Á. Humans rely on the same rules to assess emotional valence and intensity in conspecific and dog vocalizations. Biol. Lett. 2014, 10, 20130926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Molnár, C.; Pongrácz, P.; Miklósi, Á. Seeing with ears: Sightless humans’ perception of dog bark provides a test for structural rules in vocal communication. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2010, 63, 1004–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pongrácz, P.; Molnár, C.; Dóka, A.; Miklósi, Á. Do children understand man’s best friend? Classification of dog barks by pre-adolescents and adults. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 135, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, T.D. How animals communicate via pheromones. Am. Sci. 2015, 103, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pause, B.M. Processing of body odor signals by the human brain. Chemosens. Percept. 2012, 5, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penn, D.J.; Oberzauche, E.; Grammer, K.; Fischer, G.; Soini, H.A.; Wiesler, D.; Novotny, M.V.; Dixon, S.J.; Xu, Y.; Brereton, R.G. Individual and gender fingerprints in human body odor. J. R. Soc. Interface 2007, 4, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siniscalchi, M. Olfaction and the Canine Brain. In Canine Olfaction Science and Law; Jezierski, T., Ensminger, J., Papet, L.E., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 31–37. ISBN 1482260239. [Google Scholar]

- Bekoff, M. Observations of scent-marking and discriminating self from others by a domestic dog (Canis familiaris): Tales of displaced yellow snow. Behav. Process. 2001, 55, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, A. Smelling themselves: Dogs investigate their own odours longer when modified in an “olfactory mirror” test. Behav. Process. 2017, 143, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisberg, A.E.; Snowdon, C.T. The effects of sex, gonadectomy and status on investigation patterns of unfamiliar conspecific urine in domestic dogs, Canis familiaris. Anim. Behav. 2009, 77, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafazzo, S.; Natoli, E.; Valsecchi, P. Scent-marking behaviour in a pack of free-ranging domestic dogs. Ethology 2012, 118, 955–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.K. Urine marking by free-ranging dogs (Canis familiaris) in relation to sex, season, place and posture. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2003, 80, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siniscalchi, M.; Sasso, R.; Pepe, A.M.; Dimatteo, S.; Vallortigara, G.; Quaranta, A. Sniffing with the right nostril: Lateralization of response to odour stimuli by dogs. Anim. Behav. 2011, 82, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aniello, B.; Semin, G.R.; Alterisio, A.; Aria, M.; Scandurra, A. Interspecies transmission of emotional information via chemosignals: From humans to dogs (Canis lupus familiaris). Anim. Cogn. 2018, 21, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinc, L.; Bartoš, L.; Reslova, A.; Kotrba, R. Dogs discriminate identical twins. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Daly, M.; Williams, N.; Williams, S.; Williams, C.; Williams, G. Non-invasive detection of hypoglycaemia using a novel, fully biocompatible and patient friendly alarm system. BMJ 2000, 321, 1565–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berns, G.S.; Brooks, A.M.; Spivak, M. Scent of the familiar: An fMRI study of canine brain responses to familiar and unfamiliar human and dog odors. Behav. Process. 2015, 110, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhne, F.; Hoessler, J.C.; Struwe, R. Affective behavioural responses by dogs to tactile human-dog interactions. Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 2012, 125, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overall, K.L. Normal canine behavior. In Clinical Behavioral Medicine for Small Animals; Overall, K.L., Ed.; Mosby: St Louis, MO, USA, 1997; pp. 9–44. ISBN 978-0801668203. [Google Scholar]

- Miklósi, Á. Dogs in anthropogenic environments: Society and family. In Dog Behaviour, Evolution, and Cognition, 2nd ed.; Miklósi, Á., Ed.; University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 47–66. ISBN 978-0198787778. [Google Scholar]

- Baun, M.M.; Bergstrom, N.; Langston, N.F.L.T. Physiological effects of human/companion animal bonding. Nurs. Res. 1984, 33, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vormbrock, J.K.; Grossberg, J.M. Cardiovascular effects of human–pet dog interactions. J. Behav. Med. 1988, 11, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charnetski, C.J.; Riggers, S.; Brennan, F.X. Effect of petting a dog on immune system function. Psychol. Rep. 2004, 95, 1087–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostarczyk, E.; Fonberg, E. Heart rate mechanisms in instrumental conditioning reinforced by petting in dogs. Physiol. Behav. 1981, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, J. The Culture Clash. A Revolutionary New Way of Understanding the Relationship between Humans and Domestic Dogs; James & Kenneth Publishers: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-1888047059. [Google Scholar]

- Luescher, A.U.; Reisner, I.R. Canine aggression toward familiar people: A new look at an old problem. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2008, 38, 1107–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Keuster, T.; Lamoureux, J.; Kahn, A. Epidemiology of dog bites: A Belgian experience of canine behaviour and public health concerns. Vet. J. 2006, 173, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koolhaas, J.M.; Korte, S.M.; De Boer, S.F.; Van Der Vegt, B.J.; Van Reenen, C.G.; Hopster, H.; De Jong, I.C.; Ruis, M.A.W.; Blokhuis, H.J. Coping styles in animals: Current status in behavior and stress-physiology. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1999, 23, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vas, J.; Topál, J.; Gyóri, B.; Miklósi, Á. Consistency of dogs’ reactions to threatening cues of an unfamiliar person. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 112, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siniscalchi, M.; D’Ingeo, S.; Minunno, M.; Quaranta, A. Communication in Dogs. Animals 2018, 8, 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8080131

Siniscalchi M, D’Ingeo S, Minunno M, Quaranta A. Communication in Dogs. Animals. 2018; 8(8):131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8080131

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiniscalchi, Marcello, Serenella D’Ingeo, Michele Minunno, and Angelo Quaranta. 2018. "Communication in Dogs" Animals 8, no. 8: 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8080131

APA StyleSiniscalchi, M., D’Ingeo, S., Minunno, M., & Quaranta, A. (2018). Communication in Dogs. Animals, 8(8), 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8080131