The Influence of Workload and Work Flexibility on Work-Life Conflict and the Role of Emotional Exhaustion

Abstract

:1. Introduction

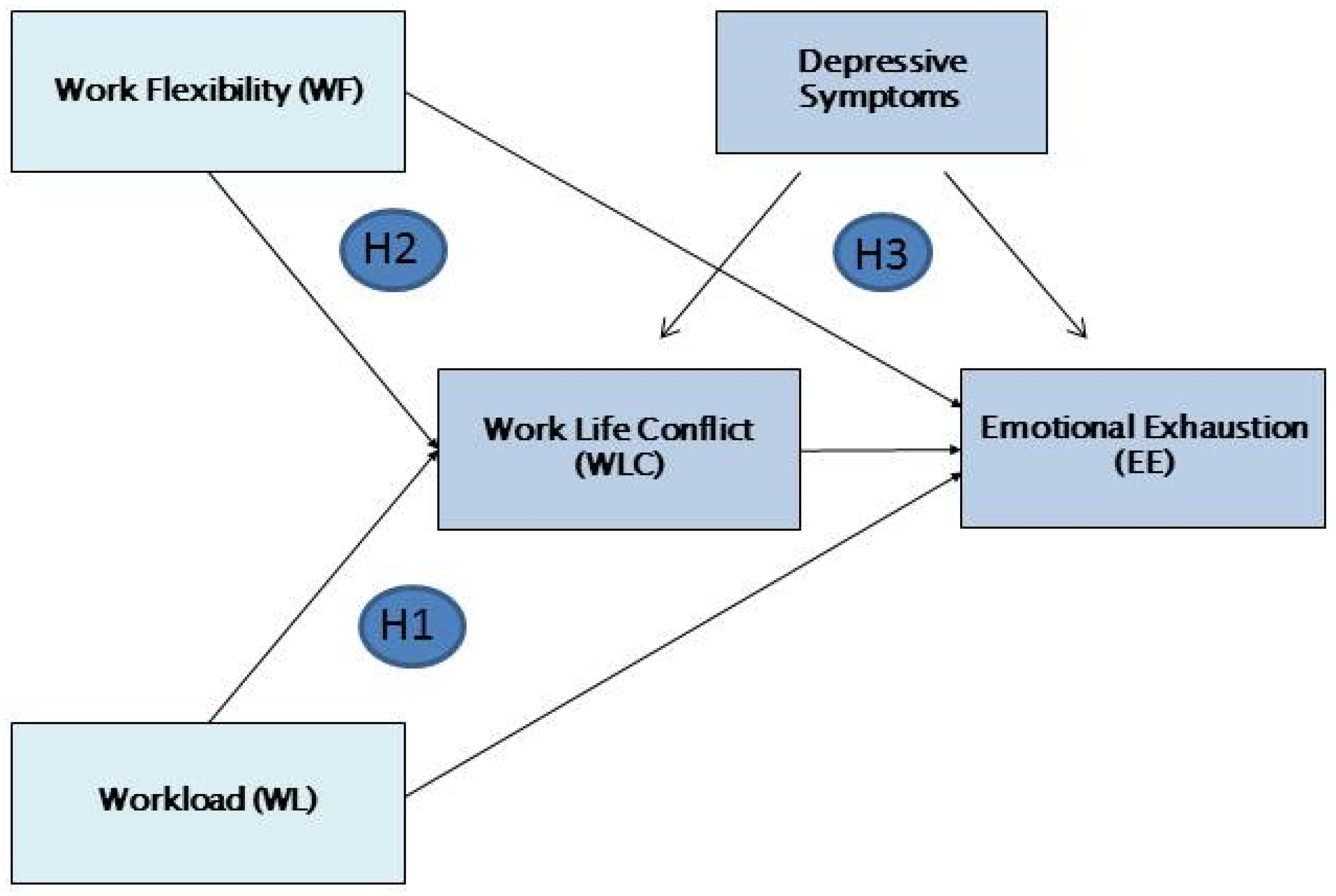

Role of the Work-Life Conflict as Mediator

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure and Sample

2.2. Measurement

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preparatory Analysis

3.2. Model Variables

3.3. Assessment and Introduction of the Model

3.4. Hypothesis 1: Direct and Indirect Effect from WL on EE via WLC

3.5. Hypothesis 2: Direct and Indirect Effect from WF on EE via WLC

3.6. Hypothesis 3: Direct and Indirect Effect from Depressive Symptoms on EE via WLC

3.7. Integration of Control Variables into the Model

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leka, S.; Jain, A.K. Health Impact of Psychosocial Hazards at Work: An Overview; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aronsson, G.; Theorell, T.; Grape, T.; Hammarstrom, A.; Hogstedt, C.; Marteinsdottir, I.; Skoog, I.; Traskman-Bendz, L.; Hall, C. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Korczak, D.; Kister, C.; Huber, B. Differentialdiagnostik des Burnout-Syndroms; Abgerufen von Deutsches Institut für Medizinische Dokumentation und Information; 2008; Available online: https://portal.dimdi.de/de/hta/hta_berichte/hta278_kurzfassung_de.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidler, A.; Thinschmidt, M.; Deckert, S.; Then, F.; Hegewald, J.; Nieuwenhuijsen, K.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. The role of psychosocial working conditions on burnout and its core component emotional exhaustion—A systematic review. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2014, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Verbeke, W. Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 43, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Dual processes at work in a call centre: An application of the job demands-resources model. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2003, 12, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, J.K.; Brotheridge, C.M. Work-family and interpersonal conflict as levers in the resource/demand-outcome relationship. Career Dev. Int. 2012, 17, 392–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, S.A.; Sonnentag, S. Recovery as an explanatory mechanism in the relation between acute stress reactions and chronic health impairment. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2006, 32, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Van Rhenen, W. How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Magee, C.A.; Stefanic, N.; Caputi, P.; Iverson, D.C. The Association between Job Demands/Control and Health in Employed Parents: The Mediating Role of Work-to-Family Interference and Enhancement. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peeters, M.C.; Montgomery, A.J.; Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B. Balancing work and home: How job and home demands are related to burnout. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2005, 12, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penz, M.; Wekenborg, M.K.; Pieper, L.; Beesdo-Baum, K.; Walther, A.; Miller, R.; Stalder, T.; Kirschbaum, C. The Dresden Burnout Study: Protocol of a prospective cohort study for the bio-psychological investigation of burnout. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 27, 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baeriswyl, S.; Krause, A.; Schwaninger, A. Emotional Exhaustion and Job Satisfaction in Airport Security Officers—Work-Family Conflict as Mediator in the Job Demands-Resources Model. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vignoli, M.; Guglielmi, D.; Bonfiglioli, R.; Violante, F.S. How job demands affect absenteeism? The mediating role of work-family conflict and exhaustion. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2016, 89, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minotte, K.L.; Gravelle, M.; Minnotte, M.C. Workplace characteristics, work-to-life conflict, and psychological distress among medical workers. Soc. Sci. J. 2013, 50, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, N.; Danjo, K.; Furukori, H.; Sato, Y.; Tomita, T.; Fujii, A.; Nakagami, T.; Kitaoka, K.; Yasui-Furukori, N. Work-family conflict as a mediator between occupational stress and psychological health among mental health nurses in Japan. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2017, 13, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, G.B.; Dollard, M.F.; Tuckey, M.R.; Winefield, A.H.; Thompson, B.M. Job demands, work-family conflict, and emotional exhaustion in police officers: A longitudinal test of competing theories. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, M.S.; Baig, M. Impact of job demands-resources model on burnout and employee’s well-being: Evidence from the pharmaceutical organizations of Karachi. Manag. Rev. 2018, 30, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leineweber, C.; Falkenberg, H.; Albrecht, S.C. Parent’s Relative Perceived Work Flexibility Compared to Their Partner Is Associated with Emotional Exhaustion. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 640–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shockley, K.M.; Allen, T.D. When flexibility helps: Another look at the availability of flexible work arrangements and work–family conflict. J. Vocat. Behav. 2007, 71, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, A.D.; Poelmans, S.A.; Allen, T.D.; Spector, P.E.; Lapierre, L.M.; Cooper, C.L.; Abarca, N.; Brough, P.; Ferreiro, P.; Fraile, G.; et al. Flexible Work Arrangements Availability and their Relationship with Work-to-Family Conflict, Job Satisfaction, and Turnover Intentions: A Comparison of Three Country Clusters. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 61, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.A. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain -implications for job redesign. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.F. Schedule Control, Work Interference with Family, and Emotional Exhaustion: A Reciprocal Moderated Mediation Model. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 2017, 11, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hwang, W.; Ramadoss, K. The job demands–Control–Support model and job satisfaction across gender: The mediating role of work–family conflict. J. Fam. Issues 2017, 38, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lesage, A.; Schmitz, N.; Drapeau, A. The relationship between work stress and mental disorders in men and women: Findings from a population-based study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2008, 62, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orosz, A.; Federspiel, A.; Haisch, S.; Seeher, C.; Dierks, T.; Cattapan, K. A biological perspective on differences and similarities between burnout and depression. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 73, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schonfeld, I.S.; Bianchi, R.; Palazzi, S. What is the difference between depression and burnout? An ongoing debate. Riv. Psichiatr. 2018, 53, 218–219. [Google Scholar]

- Wurm, W.; Vogel, K.; Holl, A.; Ebner, C.; Bayer, D.; Mörkl, S.; Szilagyi, I.-S.; Hotter, E.; Kapfhammer, H.-P.; Hofmann, P. Depression-Burnout Overlap in Physicians. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, 12–33. [Google Scholar]

- Rothe, N.; Steffen, J.; Penz, M.; Kirschbaum, C.; Walther, A. Examination of peripheral basal and reactive cortisol levels in major depressive disorder and the burnout syndrome: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 114, 232–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Ahola, K. The Job Demands-Resources model: A three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment, and work engagement. Work Stress 2008, 22, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, P.D. Missing Data Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2002, 55, 193. [Google Scholar]

- Brenscheidt, S.; Siefer, A.; Hinnenkamp, H.; Hünefeld, L. The changing worl of work, issue 2019. In Arbeitswelt im Wandel: Zahlen – Daten – Fakten. Ausgabe; 2019; Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (BAUA): Dortmund, Germany; Available online: https://www.baua.de/DE/Angebote/Publikationen/Praxis/A100.html (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Kurth, B.-M. First results from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS). Erste Ergebnisse aus der “Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland” (DEGS). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2012, 55, 980–990. Available online: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Gesundheitsmonitoring/Studien/Degs/BGBL_2012_55_BM_Kurth.pdf%3F__blob%3DpublicationFile (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, M.A.; Maske, U.E.; Ryl, L.; Schlack, R.; Hapke, U. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and diagnosed depression in adults in Germany [Prävalenz von depressiver Symptomatik und diagnostizierter Depression bei Erwachsenen in Deutschland]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundh. -Gesundh. 2013, 56, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J.; Wege, N.; Pühlhofer, F.; Wahrendorf, M. A short generic measure of work stress in the era of globalization: Effort–reward imbalance. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2009, 82, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Sage Publication: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen, T.S.; Hannerz, H.; Hogh, A.; Borg, V. The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire—A tool for the assessment and improvement of the psychosocial work environment. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2005, 31, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nübling, M.; Stößel, U.; Hasselhorn, H.-M.; Michaelis, M.; Hofmann, F. Measuring psychological stress and strain at work: Evaluation of the COPSOQ Questionnaire in Germany. GMS Psycho-Soc. Med. 2006, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey. In The Maslach Burnout Inventory-Test Manual, 3rd ed.; Maslach, C., Jackson, S.E., Leiter, M.P., Eds.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Büssing, A.; Glaser, J. Deutsche Fassung des Maslach Burnout Inventory–General Survey (MBI-GS-D); Technische Universität, Lehrstuhl für Psychologie: München, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schutte, N.; Toppinen, S.; Kalimo, R.; Schaufeli, W.B. The factorial validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS) across occupational groups and nations. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2000, 73, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brom, S.S.; Buruck, G.; Horváth, I.; Richter, P.; Leiter, M.P. Areas of worklife as predictors of occupational health—A validation study in two German samples. Burn. Res. 2015, 2, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bishara, A.J.; Hittner, J.B. Testing the significance of a correlation with nonnormal data: Comparison of Pearson, Spearman, transformation, and resampling approaches. Psychol. Methods 2012, 17, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Weiber, R.; Mühlhaus, D. Structural Equation Modeling: An Application-Oriented Introduction to Causal Analysis Using AMOS, SmartPLS and SPSS [Strukturgleichungsmodellierung: Eine Anwendungsorientierte Einführung in Die Kausalanalyse Mit Hilfe von AMOS, SmartPLS und SPSS; Springer Gabler: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publication: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The crossover of burnout and work engagement among working couples. Hum. Relat. 2005, 58, 661–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolf, M.; Müller, J. Multivariate methods: A practice-oriented introduction with application examples in SPSS (2nd, revised and revised edition). In Multivariate Verfahren: Eine Praxisorientierte Einführung Mit Anwendungsbeispielen in SPSS 2; überarb. und erw. Aufl.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M.W. Asymptotically distribution-free methods for the analysis of covariance structures. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 1984, 37, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelloway, E.K. Using LISREL for Structural Equation Modeling: A Researcher’s Guide; Sage: Sauzend Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, K.A.; Turner, N.; Barling, J.; Kelloway, E.K.; McKee, M.C. Transformational leadership and psychological well-being: The mediating role of meaningful work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zacher, H.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Bordia, P. Time pressure and coworker support mediate the curvilinear relationship between age and occupational well-being. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 462–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baeriswyl, S.; Krause, A.; Elfering, A.; Berset, M. How Workload and Coworker Support Relate to Emotional Exhaustion: The Mediating Role of Sickness Presenteeism. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2017, 24, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-offit measures. Methods Psychol. Res. 2003, 11, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Amstad, F.T.; Meier, L.L.; Fasel, U.; Elfering, A.; Semmer, N.K. A meta-analysis of work-family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. J. Occup. H. Psychol. 2011, 16, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jacobshagen, N.; Amstad, F.T.; Semmer, N.K.; Kuster, M. Work-family balance at top management level: Work-family conflict as a mediator of the relationship between stressors and strain. Z. Arb. Organ. 2005, 49, 208–219. [Google Scholar]

- Bubonya, M.; Cobb-Clark, D.A.; Ribar, D. The reciprocal between depressive symptoms and employment status. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2019, 35, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theorell, T.; Hammarstrom, A.; Aronsson, G.; Traskman Bendz, L.; Grape, T.; Hogstedt, C.; Marteinsdottir, I.; Skoog, I.; Hall, C. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dormann, C.; Zapf, D.; Perels, F. Cross and longitudinal studies in work psychology. Encyclopedia of Psychology, Subject Area D, Series III, 1 Quer-und Längsschnittstudien in der Arbeitspsychologie. In Enzyklopädie der Psychologie, Themenbereich D, Serie III, 1; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2010; pp. 923–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Hornung, S.; Weigl, M.; Glaser, J.; Angerer, P. Is It So Bad or Am I So Tired? Cross-Lagged Relationships Between Job Stressors and Emotional Exhaustion of Hospital Physicians. J. Psychol. Psychol. 2013, 12, 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M.T.; Knudsen, K. A two-wave cross-lagged study of business travel, work-family conflict, emotional exhaustion, and psychological health complaints. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2017, 26, 30–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Geurts, S.; Bakker, A.B.; Euwema, M. The impact of shiftwork on work-home conflict, job attitudes and health. Ergonomics 2004, 47, 987–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources—A New Attempt at Conceptualizing Stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansfeld, S.A.; Shipley, M.J.; Head, J.; Fuhrer, R. Repeated job strain and the risk of depression: Longitudinal analyses from the Whitehall II study. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 2360–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J.M.; Greiner, B.A.; Stansfeld, S.A.; Marmot, M. The effect of self-reported and observed job conditions on depression and anxiety symptoms: A comparison of theoretical models. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 334–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frone, M.R.; Russell, M.; Cooper, M.L. Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. J. Appl. Psychol. 1992, 77, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesmer-Magnus, J.R.; Viswesvaran, C. Convergence between measures of work-to-family and family-to-work conflict: A meta-analytic examination. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 67, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichl, C.; Leiter, M.P.; Spinath, F.M. Work-nonwork conflict and burnout: A meta-analysis. Hum. Relat. 2014, 67, 979–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.T.; Kossek, E.E.; Briscoe, J.P.; Pichler, S.; Lee, M.D. Nonwork orientations relative to career: A multidimensional measure. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijp, H.H.; Beckers, D.G.; Geurts, S.A.; Tucker, P.T.; Kompier, M.A. Systematic review on the association between employee worktime control and work-non-work balance, health and well-being, and job-related outcomes. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2012, 38, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grice, M.M.; McGovern, P.M.; Alexander, B.H. Flexible work arrangements and work–family conflict after childbirth. Occup. Med. 2008, 58, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chung, H.; van der Horst, M. Women’s employment patterns after childbirth and the perceived access to and use of flexitime and teleworking. Hum. Relat. 2018, 71, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Chang, C.-H.; Shi, J.; Zhou, L.; Shao, R. Work-Family Conflict, Emotional Exhaustion, and Displaced Aggression Toward Others: The Moderating Roles of Workplace Interpersonal Conflict and Perceived Managerial Family Support. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stab, N.; Schulz-Dadaczynski, A. Work load: An overview of association with stress consequences and work design [Arbeitsintensität: Ein Überblick zu Zusammenhängen mit Beanspruchungsfolgen und Gestaltungsempfehlungen]. Z. Arb. 2017, 71, 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Elfering, A.; Grebner, S.; de Tribolet-Hardy, F. The long arm of time pressure at work: Cognitive failure and commuting near-accidents. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2013, 22, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashill, N.J.; Rod, M. Burnout processes in non-clinical health service encounters. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Johnson, R.C.; Kiburz, K.M.; Shockley, K.M. Work-Family Conflict and Flexible Work Arrangements: Deconstructing Flexibility. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 345–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendsche, J.; Lohmann-Haislah, A.; Wegge, J. The impact of supplementary short rest breaks on task performance—A meta-analysis. Sozialpolitik.ch 2016, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, M.T.; Matthews, R.A.; Wooldridge, J.D.; Mishra, V.; Kakar, U.M.; Strahan, S.R. How do occupational stressor-strain effects vary with time? A review and meta-analysis of the relevance of time lags in longitudinal studies. Work Stress 2014, 28, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Rau, R.; Morling, K.; Rösler, U. Is there a relationship between major depression and both objectively assessed and perceived demands and control? Work Stress 2010, 24, 88–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, R.; Schonfeld, I.S.; Laurent, E. Burnout-depression overlap: A review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 36, 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, R.; Schonfeld, I.S.; Laurent, E. Is burnout separable from depression in cluster analysis? A longitudinal study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015, 50, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar]

| German-Speaking Working Adult Participants (N = 4246) | ||

|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | Scale | |

| Demographics and Education | ||

| Age | 42.71 (10.46) | 18.0–68.0 |

| Women (%) | 62.7 | |

| One or more children in the household (%) a | 28.6 | |

| University degree (%) | 55.4 | |

| Job-related characteristics | ||

| Full-time (%) | 79.8 | |

| Working Hours per Week b | 41.87 (7.08) | 21.0–62.0 |

| Duration of employment (Years) | 9.5 (9.23) | 0.0–46.0 |

| Shiftwork (%) | 13.9 | |

| Occupational Status (%) | ||

| Employees | 85.2 | |

| Freelancer | 6.1 | |

| Civil servants | 8.7 | |

| Job requirements (%) | ||

| Mostly mental | 81.3 | |

| Mostly physical | 1.8 | |

| Combined | 16.9 | |

| Mental Health Conditions | ||

| Self-reported Lifetime Diagnosed Burnout (%) | 18.3 | |

| Depressive Symptoms c | 8.36 (5.37) | 0.0–27.0 |

| Variables | α | M (SD) | Scale | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Workload (WL) | 0.73 | 9.37 (1.94) | 3–12 | 1 | |||

| 2 | Work-life conflict (WLC) | 0.90 | 51.57 (25.66) | 0–100 | 0.46 ** | 1 | ||

| 3 | Work flexibility (WF) | 0.83 | 65.72 (25.13) | 0–100 | −0.21 ** | −0.27 ** | 1 | |

| 4 | Emotional exhaustion (EE) | 0.90 | 3.08 (1.52) | 0–6 | 0.37 ** | 0.53 ** | −0.28 ** | 1 |

| 5 | Depressive Symptoms | 0.91 | 8.36 (5.37) | 0–3 | 0.28 ** | 0.44 ** | −0.24 ** |

| χ2 | df | p | RMSEA (PCLOSE) | SRMR | CFI | TLI | IFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.715 | 1 | 0.099 | 0.020 (0.946) | 0.0117 | 0.999 | 0.989 | 0.999 |

| Emotional Exhaustion | Work-Life Conflict | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Direct Effects | |

| β | β | β | |

| Main effects | |||

| Workload | 0.15 *** 0.11 *** | 0.18 *** 0.08 *** | 0.43 *** 0.35 *** |

| Work Flexibility | −0.13 *** −0.07 *** | −0.08 *** −0.03 *** | −0.18 *** −0.12 *** |

| Work-Life Conflict | 0.43 *** 0.23 *** | ||

| Depressive Symptoms | 0.54 *** (0.52−0.56) | 0.07 *** (0.06−0.08) | 0.32 *** (0.30−0.35) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buruck, G.; Pfarr, A.-L.; Penz, M.; Wekenborg, M.; Rothe, N.; Walther, A. The Influence of Workload and Work Flexibility on Work-Life Conflict and the Role of Emotional Exhaustion. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10110174

Buruck G, Pfarr A-L, Penz M, Wekenborg M, Rothe N, Walther A. The Influence of Workload and Work Flexibility on Work-Life Conflict and the Role of Emotional Exhaustion. Behavioral Sciences. 2020; 10(11):174. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10110174

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuruck, Gabriele, Anna-Lisa Pfarr, Marlene Penz, Magdalena Wekenborg, Nicole Rothe, and Andreas Walther. 2020. "The Influence of Workload and Work Flexibility on Work-Life Conflict and the Role of Emotional Exhaustion" Behavioral Sciences 10, no. 11: 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10110174

APA StyleBuruck, G., Pfarr, A.-L., Penz, M., Wekenborg, M., Rothe, N., & Walther, A. (2020). The Influence of Workload and Work Flexibility on Work-Life Conflict and the Role of Emotional Exhaustion. Behavioral Sciences, 10(11), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10110174