1. Introduction

The concept of professional burnout was first introduced in the 1960s among healthcare workers at a New York City volunteer clinic [

1]. Freudenberger, who was the first to describe professional burnout, defined it as a “multifaceted concept of physical and emotional exhaustion produced by excessive demands on the energy, strength, and resources” [

1]. However, 50 years since its introduction, a definition for burnout has yet to be agreed upon. Lisa S. Rotenstein et al., 2018, found up to 142 different definitions used in the literature [

2]. The criteria used to consider whether someone was burnt out were vastly different. As a result, the prevalence of burnout has been estimated to be zero in some studies but eighty percent in others [

2]. As no accepted standard exists to measure burnout, several measurements have been created and used in the literature. Among these measurements, the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) has gained the most attention. The MBI contains three major domains: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and personal accomplishment (PA) [

3]. In the healthcare field, EE and DP are the most common domains used to measure burnout [

4]. Several studies have looked into the consequences of burnout. For instance, studies showed that burnout is related to both poor well-being and poor job performance. Moreover, serious mental health concerns, including suicide ideation, depression, and substance use, have been linked to burnout [

5,

6,

7].

Career-wise, burnout has been related to serious thoughts of resignation or dropping out, a decline in professional work effort, unprofessional conduct, lower patient satisfaction, and reduced quality of care [

8,

9,

10]. Regarding the provision of care for different types of disorders, studies have examined which subsets could be at the highest risk of burnout. Studies found that providers serving those with psychological and behavioral disturbances, including individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), have the highest rates of burnout, stress, and resignation compared with providers serving those with other intellectual and physical disabilities [

11,

12,

13,

14].

One of the high-risk groups for various mental health issues globally is healthcare workers (HCWs). Papers published on this topic have demonstrated that HCWs are prone to problematic levels of psychological distress [

15], anxiety [

16], burnout, and emotional exhaustion [

17]. Depression, among others (anxiety, burnout, and emotional exhaustion), is the most prevalent. Studies showed that, in high-income countries, the prevalence of depression in HCWs ranged from 21.53% to 32.77% and is significantly higher than that of the general population (4.40% in 2015) [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

Moreover, researchers have disputed whether burnout and depression are similar or different in structure in recent years, as they seemingly share some common features (e.g., loss of interest and impaired concentration). However, the researchers found that the results reached were yet inconclusive, having a difference of opinion regarding the extent to which such an overlap should be expected [

23].

From a clinical perspective, burnout and depression tend to overlap with each other both at the etiological level, with unresolvable stress as the nodal (i.e., contributory) factor [

24,

25], and at the symptom level [

26,

27]. Contrarily, other researchers believe that burnout and depression are distinct. For instance, Ahola and Hakanen (2007) and Shaufeli and Enzmann (1998) illustrated in their studies that numerous investigators believe that burnout and depression are two distinct constructs and that emotional exhaustion and depression are not related. Some unanswered questions include, to what extent is burnout differentiated from depression, and do they complement each other? Burnout being mistakenly labeled as depression and/or anxiety disorders leads to inappropriate management plans, dictating how researchers must answer these critical questions [

23]. If burnout is eventually found to be indistinguishable from depression, then the clinical research on management for depression provides hope for helping working people suffering from burnout [

28].

Across several studies on burnout and psychiatry, staff who work in mental health services were found to experience high levels of burnout. Burnout has also been empirically associated with anxiety and other negative conditions [

29]. Although the link between anxiety and burnout is not fully understood, the emotional exhaustion domain of burnout correlates closely with the existence of anxiety [

23]. For instance, a study conducted in Saudi Arabia showcased that ASD is associated with higher incidences of depression and anxiety among parents and caregivers dealing with those affected by ASD, which ultimately leads to more strain and stress on those caregivers [

30]. In other studies, staff in direct contact with patients affected by ASD were found to have higher levels of anxiety and tended to encounter a variety of stressful factors that may lead them to harbor feelings of insecurity and helplessness, due to their inability to control difficult aspects encompassed by caring for these people, thus leaving them feeling emotionally depleted [

31]. Moreover, previous studies have reported that caregivers of children with ASD are at a higher risk of developing psychological stress, including anxiety and depression; of having decreased family cohesion; and of having increased somatic complaints compared with caregivers of children with other developmental disabilities. The challenges faced by these caregivers, such as the child’s difficulty with self-care, inability to communicate well, and unpredictable behaviors; social isolation; and a lack of community understanding, may pose as additional stressors, which could potentially lead to higher levels of anxiety and other negative psychological outcomes [

32,

33].

It has been established that not all patients affected by ASD are equal in terms of the severity of their symptoms. Therefore, caregivers might have to deal with patients who are more difficult. Some individuals with ASD might exhibit more self-destructive and violent behaviors, which is mainly attributed to their degree of communication and flexibility. In addition, caregivers may experience variation in the degree of challenges in facilitating routine daily activities and in seeking eye contact. All of these factors could cause more stress on people providing care to children with ASD [

31]. Nevertheless, other factors, such as the high expectations of parents, conflicts, indecisiveness, and work overload, may also put caregivers, specifically the parents of children with ASD, under chronic exposure to stress, which has been observed to affect caregivers in several domains of their lives, such as social isolation and poor mental health [

33,

34].

Autism was once considered a set of neurodevelopmental disorders known as pervasive developmental disorders (PDD). Three core deficits define these disorders: “impaired communication, impaired reciprocal social interaction, and restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviors or interests” [

35]. However, autism was revised as a diagnosis in the latest DSM revisions (DSM-V) and is known as autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Hence, ASD is now seen as a spectrum rather than as an affected disease [

36]. To address this complex neurodevelopmental disorder, specialized autism centers have been established in Saudi Arabia to support children with ASD who need personalized intensive programs that include behavioral, educational, and psychological interventions [

37].

A systematic review identified the predictors related to employment retention, turnover, burnout, and career satisfaction across samples of behavior technicians working with individuals with ASD. Several factors at the employee as well as organizational levels were classified as predictors of burnout, career satisfaction, and intention to turnover in behavior technicians and showed an increased negative implicit attitude towards patients with ASD and higher levels of burnout. In this study, a frequent turnover of behavior professionals working with those affected by ASD was also showcased to potentially negatively impact organizations, staff, and patients [

38]. Another study conducted in northern Saudi Arabia among young adults showcased the prevalence of high EE in 64.1%, high DP in 57.6%, and low PA in 32.8% [

39]. Healthcare workers, families, and teachers serving patients with autism spectrum disorder are also thought to suffer from increased rates of burnout compared with the general public [

40,

41,

42].

Given the limited number of researchers examining burnout and its relation to depression and anxiety in Saudi Arabia, the aim of our research is to find the prevalence of burnout and the levels of anxiety and depression among healthcare providers who primarily work with patients suffering from ASD and to assess the scope of its effects. The results of this research will ultimately help raise awareness of this issue and help resolve it in order to provide reliable care for patients and to maintain the mental well-being of healthcare providers.

3. Results

3.1. Reliability and Factorial Validity Analysis of the Measured Scales

The Cronbach’s alpha test of reliability suggested that the Maslach Burnout Inventory was measured reliably, with Cronbach’s alpha = 0.71, and the Areas of Worklife Survey AWS was also measured reliably, with Cronbach’s alpha = 0.75; additionally, the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 measures of anxiety and depression were measured reliably, with Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93 and 0.91, respectively (see

Appendix A Table A1). The statistical normality test findings showed that all the measured concepts were either normally distributed or have approximated normality with minor departures from normality, such as the PHQ and GAD7 total scores.

3.2. Healthcare Worker Characteristics

Three-hundred-and-eighty-one health professionals working in various autism centers in Saudi Arabia electively enrolled themselves into the study and completed and returned the online survey.

Table 1 shows the resulting findings from the analysis of their sociodemographic characteristics and work-related conditions.

3.3. Burnout Indicators

Table 2 displays the HCWs’ overall perceptions of work burnout, work–life balance satisfaction, anxiety, and depression. However,

Table A2 (see

Appendix A) shows the detailed descriptive scores of the HCWs’ perceptions of burnout for three major indicators.

The HCWs’ overall mean perceived emotional exhaustion (EE) was measured as 3.272 out of 6 points, indicating a substantial overall sense of emotional fatigue experienced by those workers. Additionally, the HCWs’ overall mean perceived sense of work-related depersonalization (DP) was measured as 1.42 points out of 6 points. This result highlights an overall low, albeit not negligible, level of depersonalization perceived by the workers serving children with autism spectrum disorders in general. Interestingly, the HCWs’ overall perceived mean personal accomplishment (PA) was relatively high, with the mean PA score for workers equal to 4.60/6 points, unveiling a substantive sense of personal accomplishment according to HCWs dealing with children diagnosed with ASD in Saudi Arabia.

3.4. Perceived Workload

Table A3 (see

Appendix A) shows a descriptive analysis of the HCWs’ perceptions on the Areas of Worklife Survey (AWS) indicators.

The HCWs’ overall mean perceived satisfaction with areas of their work and life was measured as 3.32/5 points, highlighting substantive satisfaction with their work–life balance in general, but the area of work–life rated as the most satisfying according to those HCWs was their sense of work-related reward, which received a 3.70/5 mean satisfaction rating; followed by work-related group work and community aspects, which received a 3.63/5 mean satisfaction rating; and work-related control, which received an overall mean satisfaction rating of 3.42/5.

3.5. Depression and Anxiety Levels

The HCWs’ overall perceived Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) level was rated as 9.99 points out of

21 points, SD = 6.3 points, highlighting moderate-to-high anxiety among the health personnel working with ASD, in general; however, by considering the levels of the anxiety scores based on the cut-off values for the GAD-7 scale experienced by those HCWs, 24.7% of the workers had no to low anxiety, another 23.9% were considered to have mild anxiety, another 22.8% were considered to have moderate anxiety, and 28.6% had high anxiety levels.

3.6. Variables Contributing to Burnout, Depression, and Anxiety

Table A4 (see

Appendix A) displays a descriptive analysis of the HCWs’ mean scores on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) and Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression (PHQ-9) indicators.

The HCWs’ overall mean ADL difficulties with anxiety were rated as 1.23/3 points, in general. Additionally, the HCWs’ overall mean perceived depression (PHQ-9) score was measured as 9.99/27 points, SD = 7.10 points, indicating low perceived anxiety-associated ADL difficulties in general among the autism care centers where the HCWs are residing and working in Saudi Arabia. The HCWs’ overall mean depression associated with ADL difficulty was measured at 1.02/3 points, suggestive of a low level of depression-associated ADL difficulties as well among those healthcare workers in general.

The bivariate Pearson’s correlation test results were summarized in

Table A5 (see

Appendix A). The Multivariate Linear Regression Analysis was applied to better understand what may explain why people perceived greater or lower perceptions of work-related emotional exhaustion (EE). The results from the multivariate findings (

Table 3) show that the HCWs’ sex and age did not converge significantly on their mean perceived EE at the workplace, but that the HCWs’ nationality correlated significantly with their EE perceptions. Non-Saudi employees perceived significantly lower emotional exhaustion compared with Saudi HCWs, on average (beta coefficient = −0.304,

p-value = 0). Additionally, the HCWs’ mean perceived satisfaction with their workload at their ASD care centers correlated significantly but negatively with their mean perceived EE; as the HCWs’ mean perceived satisfaction with workload increased by one point on the Likert scale, their mean perceived EE decreased by 0.448 points, on average (

p < 0.001), accounting for the other predictor variables in the analysis. Additionally, the HCWs’ mean perceived satisfaction with work-related fairness converged significantly but negatively on their EE perception score (beta = −0.207,

p < 0.001).

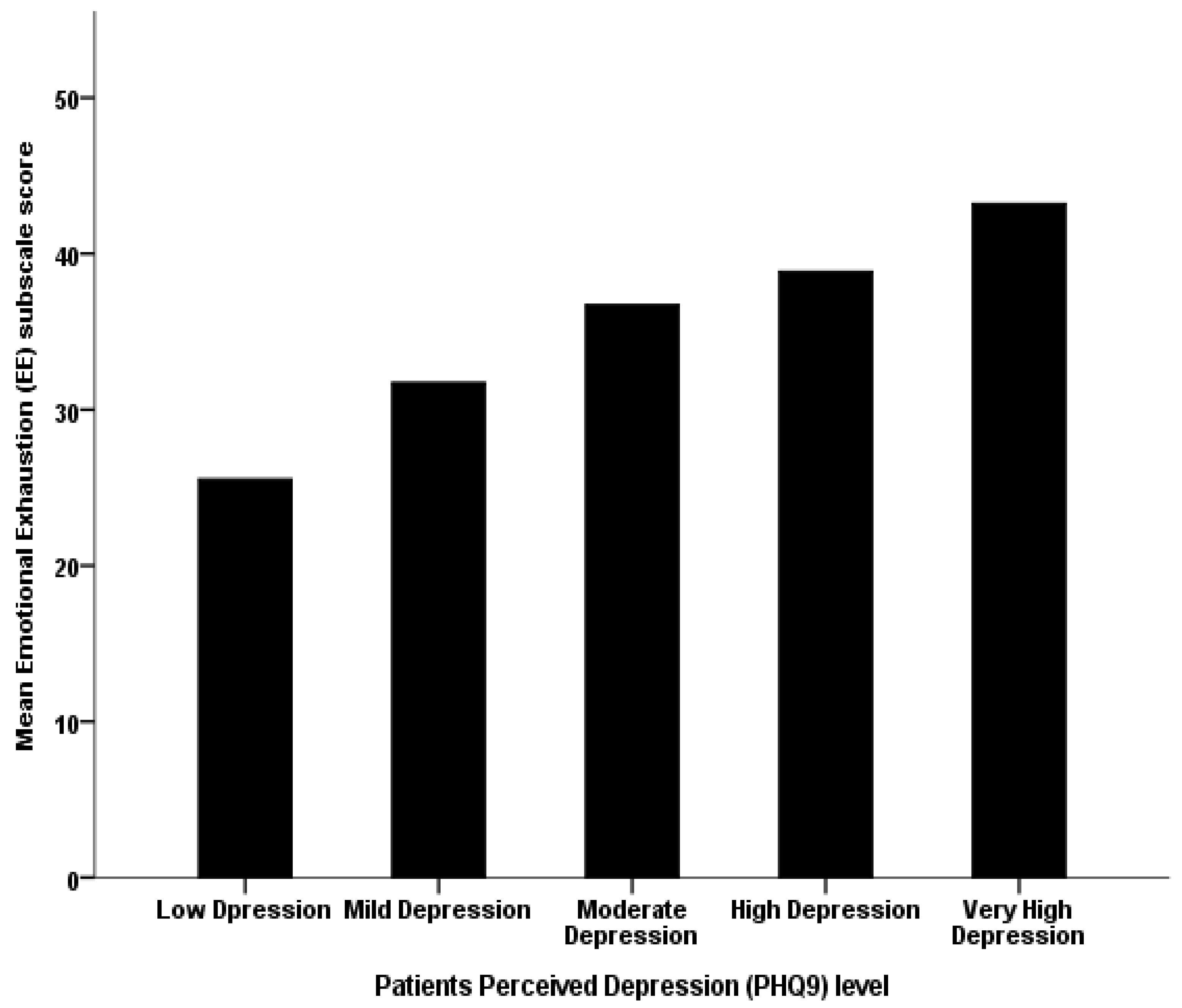

In addition, the HCWs’ mean perceived PHQ-9 depression scores converged significantly but positively on their mean perceived work-related emotional exhaustion (beta coefficient = 0.058,

p-value < 0.001); as the HCWs’ perceived depression score increased by one point on the depression PHQ9 total scale score, their corresponding mean perceived work-related emotional fatigue score tended to increase by an increment equal to 0.058, on average (see

Figure 1).

The analysis of the employees’ mean perceived work-related depersonalization (DP) with Multivariate Linear Regression Analysis (

Table 4) showed that male HCWs perceived significantly higher work-related DP compared with females, on average (beta coefficient = 0.639,

p-value ≤ 0.001), but the HCWs’ age did not converge significantly on their mean perceived DP at the workplace. Additionally, the HCWs’ nationality did not correlate significantly with their work-related DP perceptions either (

p = 0). However, the HCWs’ mean perceived PHQ-9 depression score converged significantly and positively on their mean perceived work-related sense of depersonalization (beta coefficient = 0.080,

p-value ≤ 0.001). As the HCWs’ perceived depression scores increased by one point, on average, their corresponding mean perceived work-related depersonalization (DP) scores tended to increase by an increment equal to 0.08 points, on average, too (see

Figure 2).

The resulting multivariate analysis for the mean perceived personal accomplishment (PA) of HCWs working at ASD care centers, shown in

Table 5, suggests that the HCWs’ sex does not correlate significantly with their mean perceived work-related personal accomplishment (PA) score (

p = 0.914), but workers aged between 20–29 years were found to have significantly lower mean PA scores compared with people aged thirty and older, on average (beta coefficient = −0.238,

p = 0.007;

Figure 3).

Additionally, the HCWs’ total mean perceived depression (PHQ-9) score correlated significantly but negatively with their mean perceived personal accomplishment (beta coefficient = −0.034,

p < 0.001), accounting for the other predictors in the analysis. The HCWs’ mean perceived satisfaction with work control correlated significantly and positively with their mean perceived work-related personal accomplishment (beta coefficient = 0.264,

p < 0.001). The HCWs’ mean overall perceived satisfaction with work–life areas was analyzed using multivariate regression (

Table 6).

In terms of the HCWs’ mean perceived GAD-7 score, it correlated significantly but negatively with their mean perceived satisfaction with the overall work–life score (beta coefficient = −0.021, p-value < 0.001). The HCWs’ mean perceived emotional exhaustion (EE) converged significantly but negatively on their overall mean perceived satisfaction with work–life areas (beta coefficient = −0.184, p-value < 0.001), demonstrating that greater perceived emotional fatigue among HCWs working with children with ASD predicts for less satisfaction with their work and life in general. The resulting findings also showed that the HCWs’ mean perceived personal accomplishment correlated significantly and positively with their overall mean satisfaction with their AWS score (beta coefficient = 0.226, p-value < 0.001).

4. Discussion

This is the first study to address burnout and how it is related to depression and anxiety among health professionals working with children with neurodevelopmental disabilities in Saudi Arabia at a national level. Interestingly, most of the respondents were young Saudi females with fewer than five years of experience working as frontline staff in the private sector. Although potentially considered a response gender bias, we believe this sample could reflect actual practice and the nature of the new initiatives at the governmental level, to empower the private sector to increase services in response to previous reports suggesting an action to help families who are receiving services in neighboring countries [

45].

In our sample, the HCWs’ perceptions tended to report emotional exhaustion (EE), evident by feelings that the work was hard. However, other studies conducted in healthcare workers working with individuals with disabilities provided higher feelings of fatigue in the morning when facing another day on the job and at the end of the work day [

45]. This difference might be justified, as our sample consists of younger individuals with higher qualifications. On the other hand, our sample showed that depersonalization and carelessness about patients were the lowest-rated perceptions of depersonalization (DP) at work, similar to the results in R. P. Hastings et al., 2004 [

46].

The HCWs felt that they were effective at solving patients’ problems, ranked as the top-rated perception of personal accomplishment (PA), followed by feeling that they have a positive impact on other people’s lives by working with them. R. P. Hastings et al., 2018, showed similar results, ranking them second and third highest, respectively.

In the AWS questionnaire, the subscales scores were lower (2.79–3.7) than the sample of Susan L. Ray (3.18 to 3.78) [

47]. This could be attributed to our sample being professionals working with ASD patients compared with their sample of caregivers working in mental health facilities. Our findings mostly showed a good impression regarding how HCWs felt about their work. The top indicators in four out of the six dimensions of AWS were positive, and the overall satisfaction using AWS (3.32 out 5) had a slightly higher score than the scores reported in Sarah S. Brom’s and Summer Bottini’s studies (3.28 and 2.95, respectively) [

40,

48]. We assume that this could be associated with their working experience and that most of them were specialists always dealing with ASD groups. However, our AWS score (3.32) was lower than the score from Susan L. Ray (3.55) [

47]. We found that the AWS score is negatively affected by how long work takes to finish, which might be because the HCWs work with a special population that needs more time to show the results desired. This could be resolved by increasing the number of staff and by dividing the workload among them. Additionally, our sample felt that favoritism is one of determining factors in decisions made at work, resulting in a lower score in AWS. We suggest a monthly report including the decisions made, the reasons for those decisions, and the results. Hopefully, this will ensure transparency and help reduce favoritism by showing that the decisions were made on a rational basis rather than a personal one.

Regarding the HCWs’ perceived anxiety, participants most often reported having feelings of nervousness followed by excessive worry and inability to relax, which was as previously observed in other populations [

49]. On the other hand, physical complaints including a racing heart rate, clammy extremities, and troubled breathing as well as irrational ruminating thoughts were the obvious manifestations of anxiety in different studies [

49]. The indices of stress in our sample appear to be highly exhibited among HCWs as they come across prolonged periods of intense work. More specifically, regarding factors contributing to elevated levels of stress displayed by caregivers of individuals with intellectual disability and autism, the literature identified significant impacts from restricted resource accessibility, poor work environments, a lack of expertise in managing this population, and the susceptibility of the caregiver [

50,

51]. Moreover, considerable evidence relates the degree of disability and the presence of challenging behaviors to the level of stress expressed by care-providers managing individuals with autism and other developmental disabilities [

51,

52,

53].

In terms of depression, symptoms of fatigue and disturbed sleep patterns were reported more often compared with appetite issues, loss of interest, psychomotor retardation, decreased self-esteem, and suicidal thoughts. Worth mentioning is the fact that depression is more prevalent in caregivers, and even more so in the mothers, of children with autism than with other developmental disabilities [

54]. In general, ill mental health affects around 33% of intellectual disability support workers, namely, anxiety and depression [

52]. The literature links the increased adversity rate of working with individuals with developmental disability to the high voluntary termination of work [

55]. High turnover rates among HCWs in this field are also believed to have an unfavorable impact on the quality of support and on stakeholders’ resources [

56].

The overall perception of work burnout in HCWs was strongly related to personal accomplishment (76.5%), followed by emotional exhaustion (62%) and, to a lesser extent, by depersonalization (23.7%). In contrast with other studies, emotional exhaustion ranked first (38%), followed by personal accomplishment (14%) and depersonalization (9%) [

40], mainly because, in our sample, the candidates involved themselves with the patients’ problems. In addition, receiving recognition from others as a reward might correlate with high perceptions of personal accomplishment, which was similarly shown in previous studies [

40]. This reflection is in agreement with available studies where the personal accomplishment and emotional exhaustion of HCWs showed levels comparable with those of the controls and considerably less depersonalization [

55].

Perceived anxiety among HCWs was higher than depression in our study, with percentages of 47.6% and 37%, respectively, in which the majority of anxiety was predominantly of a higher level, while depression is mainly of a moderate level. In comparison to another study [

57], this study showed that caregivers experienced more depression compared to anxiety, although the set-up was different as it specifically targeted parents. We believe that caregivers scored high on depression because of their high rate of expectations of cure and the fact that they spend more time with their children as compared to our sample.

Emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and personal accomplishment (PA) from the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) and Areas of Work Survey (AWS) are used to describe levels of burnout and how mental health is affected by the workplace. The results showed that EE in ASD center HCWs predicted for greater DP but less PA, on average, and was significantly correlated to the amount of time spent by HCWs with children with ASD and their families. This is expected, as HCWs generally are at higher risk of developing emotional exhaustion when working long hours [

17,

58]. On the other hand, those who had better satisfaction with work-related control, work-related reward, and community, as well as fairness and work-related values, were predicted to experience less EE.

A greater perceived sense of work-related accomplishment predicted for significantly lower feelings of anxiety and depression in general, while the scores for the Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety (GAD-7) and their associated Self-Rated ADL difficulties (Self-Rated ADL difficulty due to Depression (ADLDIFF1) and Self-Rated ADL difficulty due to Anxiety (ADLDIFF2)) had positive significant correlations with EE and DP and negative significant correlations with PA, with no tangible role of the length of work hours on these measures. Interestingly, DP was found to correlate significantly but negatively with all domains of AWS on the bivariate Pearson’s correlation test, while it did not correlate with the overall work–life satisfaction on the work–life areas multivariate regression. High work–life satisfaction exhibits greater PA, while being a front-line employee, a higher GAD-7, EE, and working in a governmental sector are predictors for low levels of overall work–life satisfaction. Note that, with advancements in job rankings and empowerment in the private sector, these rates could go down, along with work–life balance (WLB) interventions.

The results show a significant correlation between all aspects of the MBI (EE, DP, and PA) and HCWs’ mean perceived PHQ-9 depression scores when compared with the general population of HCWs in another study, with a significant correlation between burnout and the prevalence of depression [

59]. The complex relationship between depression and burnout and the similarity in symptoms for both might lead to misdiagnoses of burnout cases as depression. Psychiatrists have often debated whether burnout and depression are separate entities or if burnout is a form of depression [

23]. A study trying to answer this question concluded that they are “closely related, but that they are certainly not identical twins [

60]”. EE is significantly correlated with workload positively and with fairness negatively, similarly to a past study showcasing workload and fairness as the best predictors of emotional exhaustion [

40]. DP is significantly correlated with work value positively and with reward negatively, consistent with previous literature establishing a significant correlation of DP with values and reward [

40]. While we found a significantly higher mean level of DP among male HCWs, we did not notice a difference in EE or PA scores. The literature suggests that males more frequently report depersonalization than females and that females may be more predisposed to experience EE than males [

61]. Lastly, PA is significantly and positively correlated with reward, community value, and work control, similar to a study conducted previously that showed a significant correlation between all AWS scales (except workload) and PA, with values and reward being the greatest predictors of PA [

40].

People working with patients who suffer from ASD experience higher levels of burnout, and, thus, they are more prone to developing depression on top of burnout, as the relationship between burnout and the prevalence of depression is clear. This is due to HCWs experiencing higher levels of EE and DP and lower levels of PA. Factors that may aid in decreasing burnout include decreasing the workload or maintaining a workload that is on par with the worker’s expectations. In addition, establishing the organization’s values and what working at the organization is like, specifically during hiring, could be beneficial.