Research on the Influence Mechanism of Intention to Proximity Travel under the COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Proximity Travel

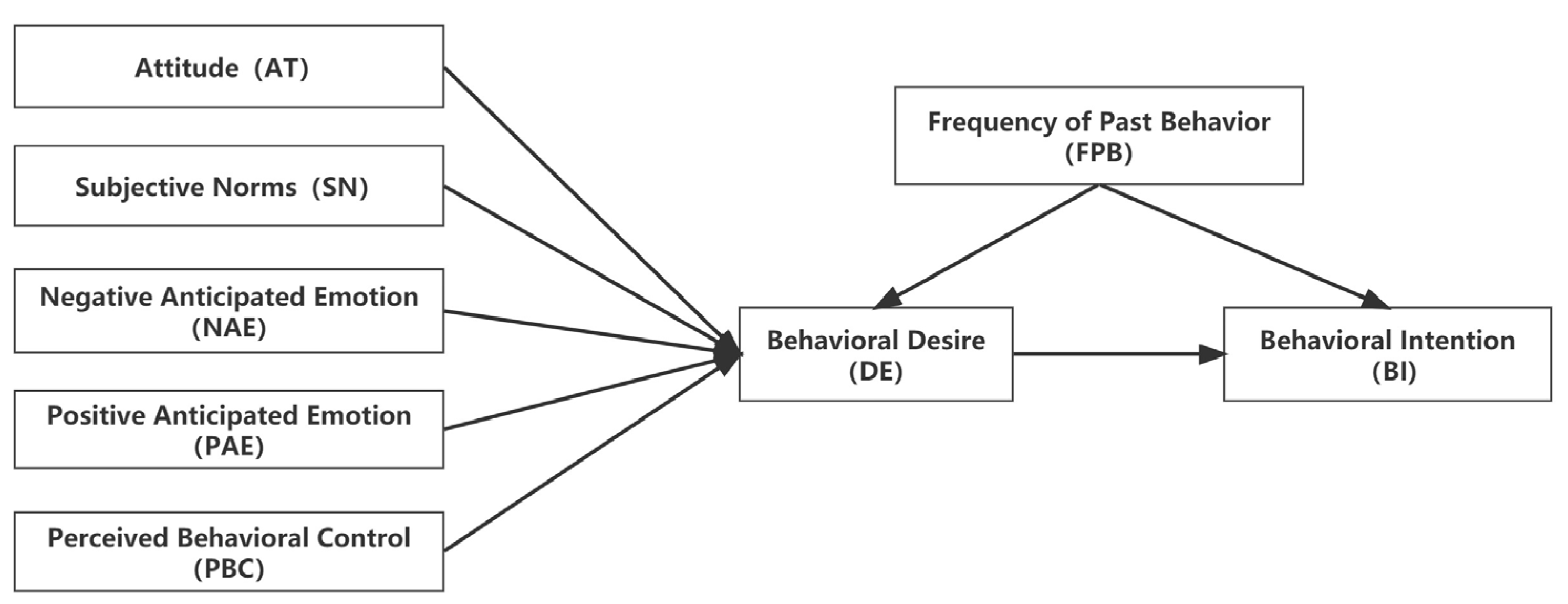

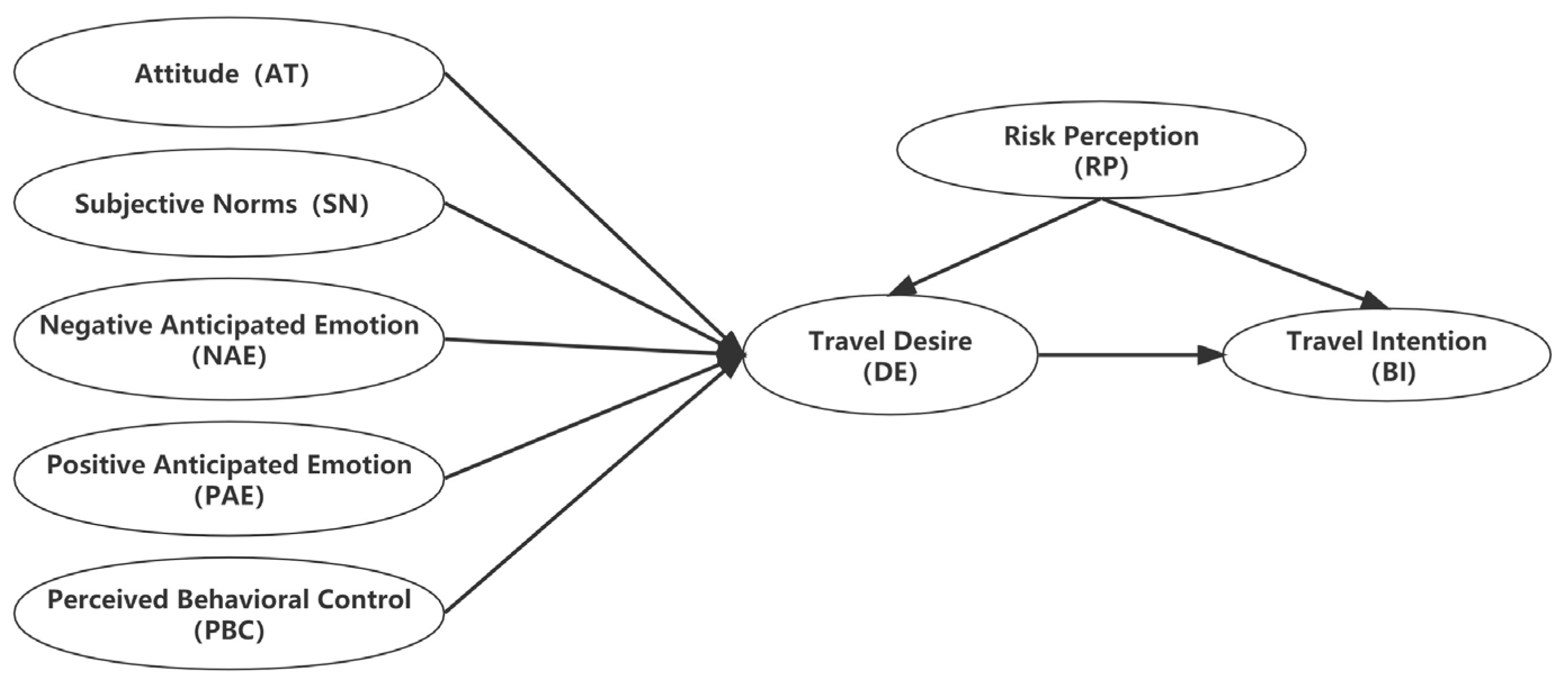

2.2. The Model of Goal-Directed Behavior

2.3. Hypotheses Development

2.3.1. Risk Perception, Attitude, Travel Desire, and Travel Intention

2.3.2. Attitude, Subjective Norm, Anticipated Emotion, Perceived Behavior Control, and Travel Desire

2.3.3. Travel Desire and Travel Intention

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Environment

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Sample and Data Collection

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Demographic Analysis

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.3. Hypothesis Test

4.3.1. Path Analysis

4.3.2. Mediating Effect Analysis

4.3.3. Indirect Effect and Total Effect Analysis

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leppin, A.; Aro, A.R. Risk perceptions related to SARS and avian influenza: Theoretical foundations of current empirical research. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 16, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ibuka, Y.; Chapman, G.B.; Meyers, L.A.; Li, M.; Galvani, A.P. The dynamics of risk perceptions and precautionary behavior in response to 2009 (H1N1) pandemic influenza. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhu, H.; Deng, F. How to influence rural tourism intention by risk knowledge during COVID-19 containment in China: Mediating role of risk perception and attitude. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheeran, P.; Harris, P.R.; Epton, T. Does heightening risk appraisals change people’s intentions and behavior? A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 511–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Bai, H.; Sun, S. How does COVID-19 affect tourism in terms of people’s willingness to travel? Empirical evidence from China. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 892–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagosa, F. The COVID-19 crisis: Opportunities for sustainable and proximity tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Soria, I. Being a tourist as a chosen experience in a proximity destination. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 96–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeuring, J.H.G.; Haartsen, T. The challenge of proximity: The (un) attractiveness of near-home tourism destinations. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 118–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rogerson, C.M.; Rogerson, J.M. COVID-19 tourism impacts in south Africa: Government and industry responses. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2020, 31, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, E.Y.T.; Jahari, S.A. Destination image as a mediator between perceived risks and revisit intention: A case of post-disaster Japan. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviours: Broadening and deepening the theory of planned behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.L.; McAleer, M.; Ramos, V. A Charter for Sustainable Tourism after COVID-19. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurdana, D.S.; Frleta, D.S.; Agbaba, R. Crisis management in tourism—Literature review. Econ. Soc. Dev. Book Proc. 2020, 1, 473–482. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Li, Z.; Yu, Z.; He, J.; Zhou, J. Communication related health crisis on social media: A case of COVID-19 Outbreak. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 269–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, N.A.; Rosbi, S. Effect of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) to tourism industry. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Res. Sci. 2020, 7, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Škare, M.; Soriano, D.R.; Porada-Rochoń, M. Impact of COVID-19 on the travel and tourism industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 163, 120469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W.; Jiang, Y. A review of research on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 102812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Subsidiarity in tourism and travel circuits in the face of climate crisis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantala, O.; Salmela, T.; Valtonen, A.; Höckert, E. Envisioning tourism and proximity after the anthropocene. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmela, T.; Nevala, H.; Nousiainen, M.; Rantala, O. Proximity tourism: A thematic literature review. Matkailututkimus 2021, 17, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, M.F.; Gibson, H.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Thapa, B. The effect of risk perceptions on Intentions to travel in the Aftermath of September 11, 2001. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2004, 15, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, G.R.; Guiver, J.W. Understanding tourists’ perceptions of distance: A key to reducing the environmental impacts of tourism mobility. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 968–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Sánchez, M.; Linares Gómez del Pulgar, M.; Tejedor Cabrera, A. Perspectives on proximity tourism planning in peri-urban areas. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2021, 30, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, G.; Ceron, J.P. Tourism/leisure greenhouse gas emissions forecasts for 2050: Factors for change in France. J. Sustain. Tour. 2006, 14, 172–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, G.; Peeters, P.; Ceron, J.P.; Gössling, S. The future tourism mobility of the world population: Emission growth versus climate policy. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2011, 45, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeuring, J.H. Discursive contradictions in regional tourism marketing strategies: The case of Fryslân, The Netherlands. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cabello, J.M.; Navarro-Jurado, E.; Thiel-Ellul, D.; Rodríguez-Díaz, B.; Ruiz, F. Assessing environmental sustainability by the double reference point methodology: The case of the provinces of Andalusia (Spain). Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2021, 28, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbisiero, F.; Monaco, S. Post-pandemic tourism resilience: Changes in Italians’ travel behavior and the possible responses of tourist cities. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 13, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, I.A.; Lin, Z.; Kou, I.E. Restoring hope and optimism through staycation programs: An application of psychological capital theory. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 1, 1970172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlGassim, A.A. The effect of COVID-19 on intraregional tourism of gulf cooperation council countries. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. 2021, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, I.D.; Coit, J.C.L. Thoughts about proximity tourism as a strategy for local development. Cuad. Tur. 2013, 32, 65–305. [Google Scholar]

- Homer, P.M.; Kahle, L.R. A structural equation test of the value-attitude-behavior hierarchy. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.K.; Gazi, M.A.I.; Bhuiyan, M.A.; Rahaman, M.A. Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on tourist travel risk and management perceptions. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Gaither, C.A. Decision making and effort in the self-regulation of hypertension: Testing two competing theories. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 505–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meng, B.; Choi, K. The role of authenticity in forming slow tourists’ intentions: Developing an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Yuan, G.; Yoo, C. The effect of the perceived risk on the adoption of the sharing economy in the tourism industry: The case of Airbnb. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 102108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.A. The addition of anticipated regret to attitudinally based, goal-directed models of information search behaviours under conditions of uncertainty and risk. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 46, 739–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Hall, C.M. Do perceived risk and intervention affect crowd funder behavior for the sustainable development goals? A model of goal-directed behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 311, 127614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Lee, C.K.; Petrick, J.F.; Kim, Y.S. The influence of perceived risk and intervention on international tourists’ behavior during the Hong Kong protest: Application of an extended model of goal-directed behavior. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 622–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Bruwer, J.; Song, H. Experiential and involvement effects on the Korean wine tourist’s decision-making process. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1215–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, L.; Perugini, M.; Ercolani, A.P. Studying, practicing, and mastering: A test of the model of goal-directed behavior (MGB) in the Software Learning Domain. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 1945–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, G.; Raya, J.M. The effect of crime perception and information format on tourists’ willingness/intention to travel. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 11, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gstaettner, A.M.; Rodger, K.; Lee, D. Visitor perspectives of risk management in a natural tourism setting: An application of the theory of planned behaviour. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2017, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, L.; De Urioste-Stone, S.; Seekamp, E.; Rahimzadeh-Bajgiran, P.; Rickard, L. Determinants of visitor climate change risk perceptions in Acadia National Park, Maine, USA. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 35, 100401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasawneh, M.; Alfandi, A.M.T. Determining behaviour intentions from the overall destination image and risk perception. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 25, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu-Lastres, B.; Ritchie, B.W.; Pan, D.Z. Risk reduction and adventure tourism safety: An extension of the risk perception attitude framework (RPAF). Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, R.N.; Real, K. Perceived risk and efficacy beliefs as motivators of change: Use of the risk perception attitude (RPA) framework to understand health behaviors. Hum. Commun. Res. 2003, 29, 370–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.; Zhu, H. Unpacking millennial Chinese women’s risk perceptions in outbound travel: An intersectional perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 49, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Chelliah, S.; Ahmed, S. Factors influencing destination image and visit intention among young women travelers: Role of travel motivation, perceived risks, and travel constraints. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 1139–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Song, H.J.; Bendle, L.J.; Kim, M.J.; Han, H. The impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions for 2009 H1N1 influenza on travel intentions: A model of goal-directed behavior. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng Yun, Y.J. Has COVID-19 Increased the intention to undertake health tourism? Examination using a conditional process model. Tour. Trib. 2022, 37, 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Kozak, M.; Wen, J. Seeing the invisible hand: Underlying effects of COVID-19 on tourists’ behavioral patterns. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 84, 888–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Lee, C.K.; Kang, S.K.; Boo, S.J. The effect of environmentally friendly perceptions on festival visitors’ decision-making process using an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1417–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.S.; Chan, K.K.; Leung, L. How consumer ethnocentrism and animosity impair the economic recovery of emerging markets. J. Glob. Mark. 2010, 23, 208–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moufakkir, O. What’s immigration got to do with it? Immigrant animosity and its effects on tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 49, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassiello, V.; Tillotson, J.S. How subjective knowledge influences intention to travel. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 80, 102851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Al-Ansi, A.; Chua, B.L.; Tariq, B.; Radic, A.; Park, S.H. The post-coronavirus world in the international tourism industry: Application of the theory of planned behavior to safer destination choices in the case of US outbound tourism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Ahmad, M.S.; Petrick, J.F.; Park, Y.N.; Park, E.; Kang, C.W. The roles of cultural worldview and authenticity in tourists’ decision-making process in a heritage tourism destination using a model of goal-directed behavior. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Jae, M.; Hwang, J. Cruise travelers’ environmentally responsible decision-making: An integrative framework of goal-directed behavior and norm activation process. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 53, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, attitude, intention and behaviour: An introduction to theory and research. Philos. Rhetor. 1977, 41, 842–844. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.R.; Ju, P.H.; Hsu, C.W. Understanding why consumers engage in electronic word-of-mouth communication: Perspectives from theory of planned behavior and justice theory. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2015, 14, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Nie, Y. Chinese Tourists’ gaming consumer behavioral intent and its influencing factors: An empirical test based on MGB theory. Tour. Trib. 2017, 32, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.J.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, C.K.; Chung, J.Y. The role of perceived ethics in the decision-making process for responsible tourism using an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 31, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yoon, H. Hotel customers’ environmentally responsible behavioral intention: Impact of key constructs on decision in green consumerism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 45, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, H.; Ahn, K.; Petrick, J.F. An integrated model of festival revisit intentions: Theory of planned behavior and festival quality/satisfaction. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 818–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Lee, S.; Peters, D.J. Iowa wetlands outdoor recreation visitors’ decision-making process: An extended model of goal-directed behavior. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2017, 17, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.L.J.; Zhou, X. Study on impact of travel intention: An empirical study facing public health emergency. Hum. Geogr. 2015, 30, 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M.; Shi, P. Chinese Tourists’ health risk avoidance behavior in the context of regular epidemic prevention and control: An empirical analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Lee, J.-S. The influence of self-efficacy, subjective norms, and risk perception on behavioral intentions related to the H1N1 flu pandemic: A comparison between Korea and the US. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 18, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seale, H.; Heywood, A.E.; McLaws, M.L.; Ward, K.F.; Lowbridge, C.P.; Van, D.; MacIntyre, C.R. Why do I need it? I am not at risk! Public perceptions toward the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 vaccine. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dai, Y.; Hao, Y.; Wu, Q. Establishment and evaluation on reliability and validity of public risk perception scale for public health emergencies. Chin. J. Public Health 2020, 36, 227–231. [Google Scholar]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Odeh, K. The role of tourists’ emotional experiences and satisfaction in understanding behavioral intentions. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K.; Whitney, D.J. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taheri, B.; Jafari, A.; Okumus, B. Ceremonious politeness in consuming food in VFR tourism: Scale development. Serv. Ind. J. 2017, 37, 948–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis. Int. Stat. Rev. 1972, 40, 394. [Google Scholar]

- Lochrie, S.; Baxter, I.W.; Collinson, E.; Curran, R.; Gannon, M.J.; Taheri, B.; Yalinay, O. Self-expression and play: Can religious tourism be hedonistic? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2019, 44, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric theory—25 years ago and now. Educ. Res. 1975, 4, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Su, L.; Swanson, S.R. The service quality to subjective well-being of Chinese tourists’ connection: A model with replications. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2076–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsuch, R.L. Exploratory factor analysis: Its role in item analysis. J. Personal. Assess. 1997, 68, 532–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wu, Z.; Bao, T.; Zhang, L. Multivariate analysis in dam monitoring data with PCA. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2010, 53, 1088–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary-Kelly, S.W.; Vokurka, R.J. The empirical assessment of construct validity. J. Oper. Manag. 1998, 16, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Canonical correlation analysis as a special case of a structural relations model. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1981, 16, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y. A Study on The Influencing Factors of Tourism Demand from Mainland China To Hong Kong. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 45, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddy, J.K. Adventure Tourism Motivations: A push and pull factor approach. Bull. Geogr. Socio Econ. Ser. 2018, 42, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vural Arslan, T.; Durak, S.; Gebesce, F.D.; Balcik, B. Assessment of factors influencing walkability in shopping streets of tourism cities: Case of Bursa, Turkey. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2018, 4, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antara, M.; Prameswari, Y.A. Push and Pull Factors of Tourists Visit the Tourism Destination of Bali, Indonesia. J. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 6, 112–120. [Google Scholar]

- Arbulú, I.; Razumova, M.; Rey-Maquieira, J.; Sastre, F. Can domestic tourism relieve the COVID-19 tourist industry crisis? The case of Spain. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golets, A.; Farias, J.; Pilati, R.; Costa, H. COVID-19 pandemic and tourism: The impact of health risk perception and intolerance of uncertainty on travel intentions. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1, 2020100432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godovykh, M.; Pizam, A.; Bahja, F. Antecedents and outcomes of health risk perceptions in tourism, following the COVID-19 pandemic. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teeroovengadum, V.; Seetanah, B.; Bindah, E.; Pooloo, A.; Veerasawmy, I. Minimising perceived travel risk in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic to boost travel and tourism. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 910–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Choe, Y.; Song, H. Korean domestic tourists’ decision-making process under threat of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.S.; Tiwari, A.K. Understanding international and domestic travel intention of Indian travelers during COVID-19 using a Bayesian approach. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 46, 228–244. [Google Scholar]

- Choe, Y.; Wang, J.; Song, H. The impact of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus on inbound tourism in South Korea toward sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1117–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. College youth travelers’ eco-purchase behavior and recycling activity while traveling: An examination of gender difference. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 740–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, I.; Font, X. Changes in air passenger demand as a result of the COVID-19 crisis: Using Big Data to inform tourism policy. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1470–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Items | Mean | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP | SE1 | 3.82 | 0.82 | 0.729 | 0.85 | 0.65 |

| SE2 | 3.80 | 0.80 | ||||

| SE3 | 3.98 | 0.79 | ||||

| CO1 | 3.78 | 0.83 | 0.734 | 0.86 | 0.67 | |

| CO2 | 3.68 | 0.79 | ||||

| CO3 | 3.74 | 0.84 | ||||

| SHE1 | 3.69 | 0.80 | 0.814 | 0.82 | 0.69 | |

| SHE2 | 3.68 | 0.86 | ||||

| PA1 | 3.74 | 0.87 | 0.792 | 0.79 | 0.66 | |

| PA2 | 3.61 | 0.75 | ||||

| AT | AT1 | 3.91 | 0.77 | 0.863 | 0.86 | 0.61 |

| AT2 | 3.64 | 0.80 | ||||

| AT3 | 3.78 | 0.77 | ||||

| AT4 | 3.57 | 0.79 | ||||

| SN | SN1 | 3.49 | 0.80 | 0.875 | 0.88 | 0.64 |

| SN2 | 3.58 | 0.80 | ||||

| SN3 | 3.55 | 0.80 | ||||

| SN4 | 3.47 | 0.80 | ||||

| PBC | PBC1 | 3.83 | 0.81 | 0.839 | 0.84 | 0.64 |

| PBC2 | 3.75 | 0.79 | ||||

| PBC3 | 3.40 | 0.80 | ||||

| PAE | PAE1 | 3.73 | 0.83 | 0.877 | 0.88 | 0.64 |

| PAE2 | 3.64 | 0.79 | ||||

| PAE3 | 3.62 | 0.80 | ||||

| PAE4 | 3.64 | 0.79 | ||||

| NAE | NAE1 | 3.02 | 0.79 | 0.879 | 0.88 | 0.65 |

| NAE2 | 2.96 | 0.81 | ||||

| NAE3 | 2.91 | 0.81 | ||||

| NAE4 | 3.08 | 0.81 | ||||

| DE | DE1 | 3.86 | 0.77 | 0.815 | 0.82 | 0.60 |

| DE2 | 3.51 | 0.81 | ||||

| DE3 | 3.67 | 0.74 | ||||

| TI | TI1 | 3.89 | 0.80 | 0.879 | 0.88 | 0.65 |

| TI2 | 3.59 | 0.80 | ||||

| TI3 | 3.58 | 0.81 | ||||

| TI4 | 3.71 | 0.82 |

| SE | CO | SHE | PA | SN | PBC | PAE | NAE | AT | DE | TI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE | 0.81 | ||||||||||

| CO | 0.50 ** | 0.82 | |||||||||

| SHE | 0.47 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.83 | ||||||||

| PA | 0.48 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.81 | |||||||

| SN | 0.15 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.80 | ||||||

| PBC | 0.23 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.80 | |||||

| PAE | 0.20 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.80 | ||||

| NAE | 0.05 * | 0.06 * | 0.08 * | 0.03 * | 0.00 * | 0.12 * | 0.02 * | 0.81 | |||

| AT | 0.32 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.09 * | 0.78 | ||

| DE | 0.27 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.01 * | 0.43 ** | 0.77 | |

| TI | 0.47 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.04 * | 0.45 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.81 |

| AVE | 0.65 ** | 0.67 ** | 0.69 ** | 0.66 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.65 ** | 0.61 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.65 ** |

| Χ2/df | RMSEA | TLI | CFI | AGFI | GFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Values | 1.87 | 0.042 | 0.947 | 0.952 | 0.887 | 0.904 |

| Optimal value | <3.0 | <0.08 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.80 | >0.80 |

| Standard value | 3.0~5.0 | 0.08~0.10 | 0.70~0.90 | 0.70~0.90 | 0.70~0.90 | 0.70~0.90 |

| Hypothesis | Estimate | Standard Error | CR | p | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | 0.618 | 0.069 | 9.795 | *** | Accepted |

| H2 | 0.193 | 0.087 | 2.345 | * | Accepted |

| H3 | 0.625 | 0.079 | 9.014 | *** | Accepted |

| H4 | 0.171 | 0.063 | 2.623 | ** | Accepted |

| H5 | 0.144 | 0.039 | 2.890 | ** | Accepted |

| H6 | 0.224 | 0.044 | 4.158 | *** | Accepted |

| H7 | −0.053 | 0.031 | −1.166 | 0.244 | Rejected |

| H8 | 0.201 | 0.046 | 3.689 | *** | Accepted |

| H9 | 0.179 | 0.060 | 3.226 | *** | Accepted |

| Path | Estimate | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | Proportion of Mediation Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP → AT → DE | 0.264 | 0.169 | 0.358 | 36.4% |

| RP → DE → TI | 0.495 | 0.405 | 0.585 | 17.5% |

| Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE | TI | DE | TI | DE | TI | |

| RP | 0.264 *** | 0.495 *** | 0.151 *** | 0.105 *** | 0.414 *** | 0.601 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, H.; Wang, L.; Xu, S.; Law, R.; Zhang, M. Research on the Influence Mechanism of Intention to Proximity Travel under the COVID-19. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010010

Chen H, Wang L, Xu S, Law R, Zhang M. Research on the Influence Mechanism of Intention to Proximity Travel under the COVID-19. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Huan, Luyao Wang, Shaogui Xu, Rob Law, and Mu Zhang. 2023. "Research on the Influence Mechanism of Intention to Proximity Travel under the COVID-19" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010010