Exploring the Social Trend Indications of Utilizing E-Commerce during and after COVID-19’s Hit

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. COVID-19 Global Impact

2.2. E-Commerce Market

3. The Gap and Research Questions

- What are the social behavior and demands of individuals toward utilizing e-commerce and services during and after the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia and Egypt?

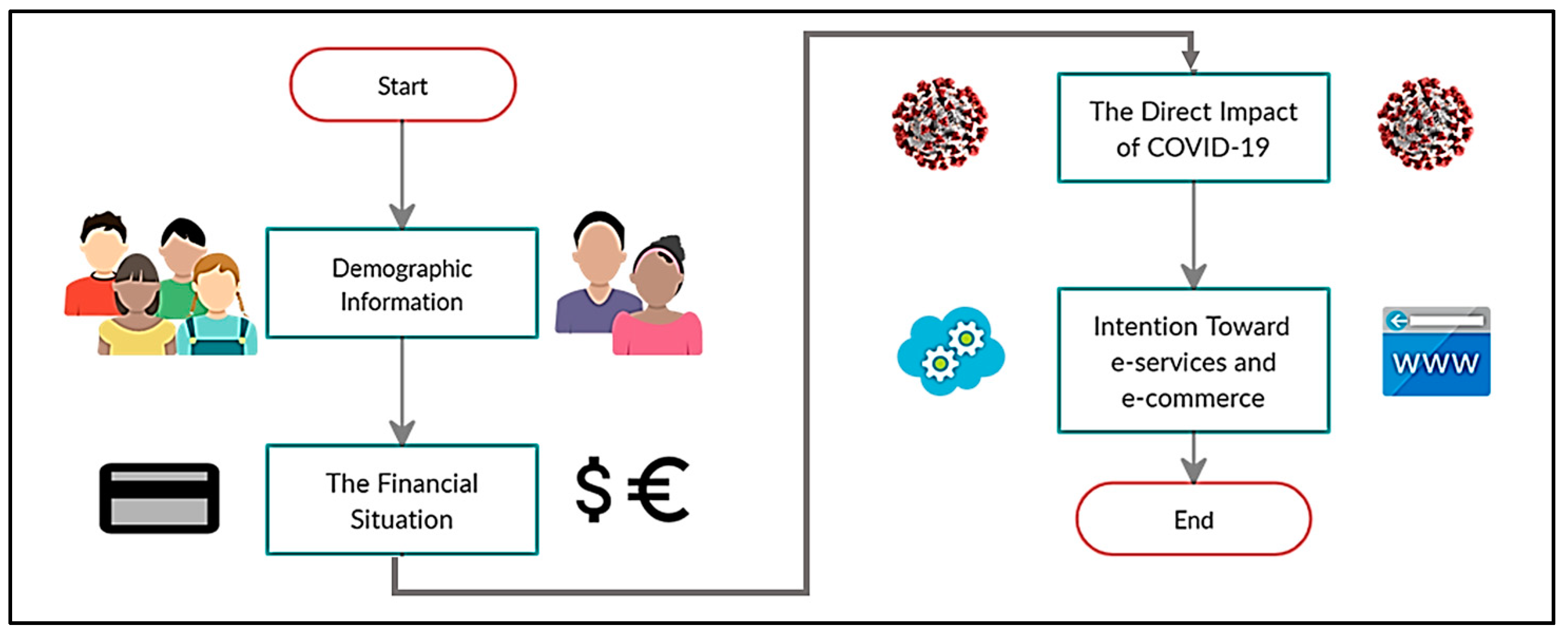

4. Methodology

- Selecting the correct sample, such as the geographical location and the age;

- Preparing data for analysis at the preprocessing stage. This included removing incomplete records and incorrect entries.

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Demographic Analysis

5.2. Health Impact of COVID-19

5.3. Trend Analysis

5.4. Regression Analysis

6. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.1. Principal Findings

6.2. The Effect of COVID-19

7. Conclusions

8. Limitations

Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Corona Virus Disease 2019 |

| E-commerce | Electronic commerce |

| E-services | Electronic services |

| EGP | Egyptian Pound (the currency of Egypt) |

| ICT | Information and communication technology |

| MENA | Middle East and North Africa |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| RRT | Renal Replacement Therapy |

| SAR | Saudi Riyal (the currency of Saudi Arabia) |

| UAE | United Arab Emirates |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Cao, Z.; Tang, F.; Chen, C.; Zhang, C.; Guo, Y.; Lin, R.; Huang, Z.; Teng, Y.; Xie, T.; Xu, Y.; et al. Impact of systematic factors on the outbreak outcomes of the novel COVID-19 disease in china: Factor analysis study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e23853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.-Q.; Cheng, Z.J.; Duan, Z.; Tian, L.; Hakonarson, H. The infection rate of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: Combined analysis of population samples. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e20914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzanegan, M.R.; Gholipour, H.F.; Feizi, M.; Nunkoo, R.; Andargoli, A.E. International tourism and outbreak of coronavirus (COVID-19): A cross-country analysis. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabara, D. High-tech offers on ecommerce platform during war in Ukraine. Ann. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2022, 32, 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Amankwah-Amoah, J.; Khan, Z.; Wood, G.; Knight, G. COVID-19 and digitalization: The great acceleration. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 136, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happonen, A.; Tikka, M.; Usmani, U.A. A systematic review for organizing hackathons and code camps in COVID-19 like times: Literature in demand to understand online hackathons and event result continuation. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Data and Software Engineering (ICoDSE), Bandung, Indonesia, 3–4 November 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Happonen, A.; Santti, U.; Auvinen, H.; Räsänen, T.; Eskelinen, T. Digital age business model innovation for sustainability in university industry collaboration model. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 211, 04005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margherita, A.; Heikkilä, M. Business continuity in the COVID-19 emergency: A framework of actions undertaken by world-leading companies. Bus. Horiz. 2021, 64, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Who Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2022. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Worldometers. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. 2022. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Berger, Z.D.; Evans, N.G.; Phelan, A.L.; Silverman, R.D. COVID-19: Control measures must be equitable and inclusive. BMJ 2020, 368, m1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daoust, J.F. Elderly people and responses to COVID-19 in 27 countries. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zandvoort, K.; Jarvis, C.I.; Pearson, C.; Davies, N.G.; Russell, T.W.; Kucharski, A.J.; Jit, M.J.; Flasche, S.; Eggo, R.M.; Checchi, F. Response strategies for COVID-19 epidemics in african settings: A mathematical modelling study. MedRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jawad, A.J. Effectiveness of population density as natural social distancing in COVID-19 spreading. Ethics Med. Public Health 2020, 15, 100556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnikrishnan, A.; Figliozzi, M. Exploratory analysis of factors affecting levels of home deliveries before, during, and post- COVID-19. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 10, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Hashimoto, M. Changes in consumer dynamics on general e-commerce platforms during the COVID-19 pandemic: An exploratory study of the japanese market. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofer, J.L.; Mahmassani, H.S.; Ng, M.T.M. Resilience of U.S. Rail intermodal freight during the COVID-19 pandemic. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 43, 100791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Music, J.; Charlebois, S.; Toole, V.; Large, C. Telecommuting and food e-commerce: Socially sustainable practices during the COVID-19 pandemic in canada. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2022, 13, 100513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, J.; Weekx, S.; Beutels, P.; Verhetsel, A. COVID-19 and retail: The catalyst for e-commerce in belgium? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilińska-Reformat, K.; Dewalska-Opitek, A. E-commerce as the predominant business model of fast fashion retailers in the era of global COVID-19 pandemics. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 192, 2479–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, A.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, F. How would the COVID-19 pandemic reshape retail real estate and high streets through acceleration of e-commerce and digitalization? J. Urban Manag. 2021, 10, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djalante, R.; Nurhidayah, L.; Van Minh, H.; Phuong, N.T.N.; Mahendradhata, Y.; Trias, A.; Lassa, J.; Miller, M.A. COVID-19 and asean responses: Comparative policy analysis. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 8, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.W.S.; Lee, S.; Dong, M.C.; Taniguchi, M. What factors drive the satisfaction of citizens with governments’ responses to COVID-19? Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 102, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Zare, S. COVID-19 and Airbnb—disrupting the disruptor. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. The effect of the COVID-19 on sharing economy activities. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 124782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh-Brown, M.R.; Jensen, H.T.; Edmunds, W.J.; Smith, R.D. The impact of COVID-19, associated behaviours and policies on the uk economy: A computable general equilibrium model. SSM Popul. Health 2020, 100651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uğur, N.G.; Akbıyık, A. Impacts of COVID-19 on global tourism industry: A cross-regional comparison. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newburger, E.; Jeffery, A. As coronavirus restrictions empty streets around the world, wildlife roam further into cities. In ENVIRONMENT; CNBC Online: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S.; Saha, M.; Dhar, B.; Pandit, S.; Nasrin, R. Geospatial analysis of COVID-19 lockdown effects on air quality in the south and southeast asian region. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 756, 144009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, T.; Grey, I.; Östlundh, L.; Lam, K.B.H.; Omar, O.M.; Arnone, D. The prevalence of psychological consequences of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 805–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triberti, S.; Durosini, I.; Pravettoni, G. Social distancing is the right thing to do: Dark triad behavioral correlates in the COVID-19 quarantine. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 170, 110453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, L.; Protopopova, A.; Birkler, R.I.D.; Itin-Shwartz, B.; Sutton, G.A.; Gamliel, A.; Yakobson, B.; Raz, T. Human–dog relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic: Booming dog adoption during social isolation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, K.; Torous, J.; Caine, E.D.; De Choudhury, M. Psychosocial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic: Large-scale quasi-experimental study on social media. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadim, M.K.; Forni, L.G.; Mehta, R.L.; Connor, M.J.; Liu, K.D.; Ostermann, M.; Rimmelé, T.; Zarbock, A.; Bell, S.; Bihorac, A.; et al. COVID-19-associated acute kidney injury: Consensus report of the 25th acute disease quality initiative (adqi) workgroup. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 747–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marroquín, B.; Vine, V.; Morgan, R. Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Effects of stay-at-home policies, social distancing behavior, and social resources. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, J.; Timsina, J.; Khadka, S.R.; Ghale, Y.; Ojha, H. COVID-19 impacts on agriculture and food systems in Nepal: Implications for sdgs. Agric. Syst. 2021, 186, 102990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kansiime, M.K.; Tambo, J.A.; Mugambi, I.; Bundi, M.; Kara, A.; Owuor, C. COVID-19 implications on household income and food security in kenya and uganda: Findings from a rapid assessment. World Dev. 2021, 137, 105199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Khan, N.A.; Hussain, S. The COVID 19 pandemic and digital higher education: Exploring the impact of proactive personality on social capital through internet self-efficacy and online interaction quality. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacin, V.; Ginnane, S.; Ferrario, M.A.; Happonen, A.; Wolff, A.; Piutunen, S.; Kupiainen, N. SENSEI: Harnessing Community Wisdom for Local Environmental Monitoring in Finland. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santti, U.; Eskelinen, T.; Rajahonka, M.; Villman, K.; Happonen, A. Effects of business model development projects on organizational culture: A multiple case study of smes. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2017, 7, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happonen, A.; Siljander, V. Gainsharing in logistics outsourcing: Trust leads to success in the digital era. Int. J. Collab. Enterp. 2020, 6, 150–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibn-Mohammed, T.; Mustapha, K.B.; Godsell, J.; Adamu, Z.; Babatunde, K.A.; Akintade, D.D.; Acquaye, A.; Fujii, H.; Ndiaye, M.M.; Yamoah, F.A.; et al. A critical analysis of the impacts of COVID-19 on the global economy and ecosystems and opportunities for circular economy strategies. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras, J.; Happonen, A.; Khakurel, J. In Experiences and Lessons Learned from Onsite and Remote Teamwork Based Courses in Software Engineering. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Data and Software Engineering (ICoDSE), Online, 3–4 November 2021; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Karma, I.; Darma, I.K.; Santiana, I. Blended learning is an educational innovation and solution during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Res. J. Eng. IT Sci. Res. 2021, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, B.N. Stock markets’ reaction to COVID-19: Moderating role of national culture. Financ. Res. Lett. 2020, 41, 101857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekoya, O.B.; Oliyide, J.A.; Oduyemi, G.O. How COVID-19 upturns the hedging potentials of gold against oil and stock markets risks: Nonlinear evidences through threshold regression and markov-regime switching models. Resour. Policy 2020, 70, 101926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T. COVID-19’s impact on stock prices across different sectors—An event study based on the chinese stock market. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2020, 56, 2198–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happonen, A.; Minashkina, D. Professionalism in Esport: Benefits in Skills and Health & Possible Downsides; LUT University: Lappeenranta, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, L.; Diagne, M.; Wang, W.; Gao, J. Country distancing increase reveals the effectiveness of travel restrictions in stopping COVID-19 transmission. Commun. Phys. 2021, 4, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Sohn, J. Passenger, airline, and policy responses to the COVID-19 crisis: The case of south Korea. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2022, 98, 102144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiopu, A.F.; Hornoiu, R.I.; Padurean, M.A.; Nica, A.-M. Virus tinged? Exploring the facets of virtual reality use in tourism as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 60, 101575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsyth, P.; Guiomard, C.; Niemeier, H.-M. COVID-19, the collapse in passenger demand and airport charges. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 89, 101932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotle, S.; Mumbower, S. The impact of COVID-19 on domestic U.S. Air travel operations and commercial airport service. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 9, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volgger, M.; Taplin, R.; Aebli, A. Recovery of domestic tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic: An experimental comparison of interventions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya Calderón, M.; Chavarría Esquivel, K.; Arrieta García, M.M.; Lozano, C.B. Tourist behaviour and dynamics of domestic tourism in times of COVID-19. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 25, 2207–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellenius, G.A.; Vispute, S.; Espinosa, V.; Fabrikant, A.; Tsai, T.C.; Hennessy, J.; Dai, A.; Williams, B.; Gadepalli, K.; Boulanger, A.; et al. Impacts of social distancing policies on mobility and COVID-19 case growth in the us. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M. Understanding the customer psychology of impulse buying during COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for retailers. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2020, 19, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, S.; Toussaint, E.C. Food access in crisis: Food security and COVID-19. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 180, 106859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamda. How COVID-19 Unlocked the Adoption of e-Commerce in the Mena Region. 2021. Available online: https://www.wamda.com/research/covid-19-unlocked-adoption-e-commerce-mena-region (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- EUROMONITOR. E-Commerce in Saudi Arabia. 2021. Available online: https://www.euromonitor.com/e-commerce-in-saudi-arabia/report# (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- EUROMONITOR. Pandemic Drives a Surge in Online Shopping. 2021. Available online: https://www.euromonitor.com/e-commerce-in-egypt/report (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- researchandmarkets.com. Africa and Middle East b2c Ecommerce Market Opportunities Databook—100+ KPIs on Ecommerce Verticals, Market Share by Key Players, Sales Channel Analysis, Payment Instrument, Consumer Demographics—q2 2022 Update. 2022. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5648283/africa-and-middle-east-b2c-ecommerce-market?utm_source=CI&utm_medium=PressRelease&utm_code=r2p4dv&utm_campaign=1756163+-+Africa+and+Middle+East+B2C+e-Commerce+Market+Report+2022-2026%3a+e-Commerce+in+the+MENA+is+Swiftly+Catching+Up+to+Global+Superpowers+Like+United+States+and+China&utm_exec=chdo54prd (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- EcommerceDB. The Ecommerce Market in Saudi Arabia. 2021. Available online: https://ecommercedb.com/en/markets/sa/all (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Statista. E-Commerce Market in Saudi Arabia—Statistics & Facts. 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/7723/e-commerce-in-saudi-arabia/ (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Tiwari, K. Rising Kingdom of Ecommerce: Post-Covid Online Retail Trends in Saudi Arabia. 2021. Available online: https://www.capillarytech.com/blog/capillary/ecommerce/ecommerce-in-saudi-arabia-growth-trends-opportunities-2/ (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- ITA. Egypt—Country Commercial Guide; U.S. Department of Commerce. 2021. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/egypt-ecommerce (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- EcommerceDB. The Ecommerce Market in Egypt. 2021. Available online: https://ecommercedb.com/en/markets/eg/all (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- NasdaqGS. Amazon.com, Inc. (amzn). 2020. Available online: https://yhoo.it/2KQ9kaX (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- NasdaqGS. Ebay Inc. (eBay). 2020. Available online: https://yhoo.it/39BCRzB (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Minashkina, D.; Happonen, A. Decarbonizing warehousing activities through digitalization and automatization with WMS integration for sustainability supporting operations. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences of the 2019 7th International Conference on Environment Pollution and Prevention (ICEPP 2019), Melbourne, Australia, 18–20 December 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happonen, A.; Minashkina, D. Operations Automatization and Digitalization–A Research and Innovation Collaboration in Physical Warehousing, Improvement Ideas in AS/RS and 3PL Logistics Context; LUT Research Reports Series Report 104; LUT University: Lappeenranta, Finland, 2019; pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Palacin, V.; Gilbert, S.; Orchard, S.; Eaton, A.; Ferrario, M.A.; Happonen, A. Drivers of participation in digital citizen science: Case studies on Järviwiki and Safecast. Citiz. Sci. Theory Pract. 2020, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilan, D.; Balderas-Cejudo, A.; Fernández-Lores, S.; Martinez-Navarro, G. Innovation in online food delivery: Learnings from COVID-19. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 24, 100330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter Michael, E. Competitive strategy. Meas. Bus. Excell. 1997, 1, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, C.; Fosso-Wamba, S.; Arnaud, J.B. Online consumer resilience during a pandemic: An exploratory study of e-commerce behavior before, during and after a COVID-19 lockdown. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Patnaik, R.; More, U. Pre-and post-analysis of consumer behavior during COVID-19 lockdown for online shopping. PalArch’s J. Archaeol. Egypt/Egyptol. 2021, 18, 2288–2301. [Google Scholar]

- Onjewu, A.-K.E.; Hussain, S.; Haddoud, M.Y. The interplay of e-commerce, resilience and exports in the context of COVID-19. Inf. Syst. Front. 2022, 24, 1209–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, A.; Hassan, R.; Abdullah, N.I.; Hussain, A.; Fareed, M. Covid-19 impact on e-commerce usage: An empirical evidence from malaysian healthcare industry. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2020, 8, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís Arce, J.S.; Warren, S.S.; Meriggi, N.F.; Scacco, A.; McMurry, N.; Voors, M.; Syunyaev, G.; Malik, A.A.; Aboutajdine, S.; Adeojo, O.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in low- and middle-income countries. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierron, D.; Pereda-Loth, V.; Mantel, M.; Moranges, M.; Bignon, E.; Alva, O.; Kabous, J.; Heiske, M.; Pacalon, J.; David, R.; et al. Smell and taste changes are early indicators of the COVID-19 pandemic and political decision effectiveness. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.W.; Luisi, N.; Zlotorzynska, M.; Wilde, G.; Sullivan, P.; Sanchez, T.; Bradley, H.; Siegler, A.J. Willingness to use home collection methods to provide specimens for SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 research: Survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, C.; Nie, X.; Wu, A.; Li, X. Return to normal pre-COVID-19 life is delayed by inequitable vaccine allocation and SARS-CoV-2 variants. Epidemiol. Infect. 2022, 150, e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographics and Variable | Frequency n, (%) |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| Saudi Arabia | 104, (67%) |

| Egypt | 51, (33%) |

| Age (Years) | |

| 18–30 | 91, (59%) |

| 31–40 | 45, (29%) |

| 41–50 | 14, (9%) |

| ≥51 | 5, (3%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 82, (53%) |

| Female | 73, (47%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 84, (54%) |

| Married | 69, (45%) |

| Divorced | 2, (1%) |

| Employment Status | |

| Student | 14, (9%) |

| Employed—Government Sector | 24, (15%) |

| Employed—Private Sector | 42, (27%) |

| Business Owner | 12, (8%) |

| Unemployed | 63, (41%) |

| Monthly Income in the Local Currency | |

| Less than 10 K | 107, (69%) |

| From 10 k to 20 K | 32, (21%) |

| More than 20 K | 16, (10%) |

| Change in Monthly Income Because of COVID-19 | |

| Reduced | 71, (46%) |

| Increased | 4, (3%) |

| Remained the Same | 80, (52%) |

| Highest Hourly Curfew Duration per Day | |

| ¼ of the day (0 to 6 h) | 7, (5%) |

| ½ of the day (>6 to 12 h) | 51, (33%) |

| ¾ of the day (>12 to 18 h) | 27, (17%) |

| Most of or the entire day (>18 to 24 h) | 70, (45%) |

| Infection/Death by COVID-19 | Frequency * n, (%) |

|---|---|

| Infection by COVID-19 | |

| No | 88, (57%) |

| Yes—Me | 17, (11%) |

| Yes—My Family | 33, (21%) |

| Yes—Relatives or Friends | 42, (27%) |

| Death by COVID-19 | |

| No | 115, (74%) |

| Yes—My Family | 5, (3%) |

| Yes—Relatives or Friends | 39, (25%) |

| Stage No. | Time Period of COVID-19 | Average * | Standard Deviation * |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Before the pandemic | 0.55 | 0.26 |

| 2 | During the outbreak and the curfew | 0.63 | 0.28 |

| 3 | During the ease and the social distancing | 0.57 | 0.36 |

| 4 | After the pandemic | 0.60 | 0.34 |

| Activity No. | Online Activity | Frequency * n, (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before the Pandemic | During the Outbreak and Curfew | During the Ease and Social Distancing | After the Pandemic | Never Like | ||

| 1 | Buying food and groceries | 20, (13%) | 66, (43%) | 32, (21%) | 23, (15%) | 68, (44%) |

| 2 | Buying cooked and fast food to be delivered via mobile app services | 45, (29%) | 80, (52%) | 54, (35%) | 47, (30%) | 44, (28%) |

| 3 | Buying hygiene products | 28, (18%) | 60, (39%) | 29, (19%) | 22, (14%) | 71, (46%) |

| 4 | Buying clothes | 51, (33%) | 66, (43%) | 58, (37%) | 43, (28%) | 49, (32%) |

| 5 | Buying electronic devices | 40, (26%) | 52, (34%) | 50, (32%) | 41, (26%) | 60, (39%) |

| 6 | Buying medicines and supplements | 20, (13%) | 50, (32%) | 38, (25%) | 17, (11%) | 77, (50%) |

| 7 | Subscribing to online TV and video streaming services | 60, (39%) | 86, (55%) | 53, (34%) | 47, (30%) | 45, (29%) |

| 8 | Subscribing to online gaming services | 26, (17%) | 55, (35%) | 31, (20%) | 24, (15%) | 79, (51%) |

| 9 | Subscribing to online meeting services | 45, (29%) | 103, (66%) | 61, (39%) | 44, (28%) | 32, (21%) |

| COVID-19 Effect | # of Groups | During the Social Distancing Period | After COVID-19 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F Value (df) | p Value | F Value (df) | p Value | ||

| Infection | 4 | 0.003 (3, 151) | 0.955 | 0.112 (3, 151) | 0.739 |

| Death | 3 | 0.111 (2, 152) | 0.739 | 0.035 (2, 152) | 0.852 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fakieh, B.; Happonen, A. Exploring the Social Trend Indications of Utilizing E-Commerce during and after COVID-19’s Hit. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010005

Fakieh B, Happonen A. Exploring the Social Trend Indications of Utilizing E-Commerce during and after COVID-19’s Hit. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleFakieh, Bahjat, and Ari Happonen. 2023. "Exploring the Social Trend Indications of Utilizing E-Commerce during and after COVID-19’s Hit" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010005

APA StyleFakieh, B., & Happonen, A. (2023). Exploring the Social Trend Indications of Utilizing E-Commerce during and after COVID-19’s Hit. Behavioral Sciences, 13(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010005