The Relationship between the Family Environment and Eating Disorder Symptoms in a Saudi Non-Clinical Sample of Students: A Moderated Mediated Model of Automatic Thoughts and Gender

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Family Environment and Eating Disorder Symptoms

1.2. The Mediating Role of Negative Automatic Thoughts

1.3. The Moderation of Gender

2. Methods

2.1. Data and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Testing the Mediation Model

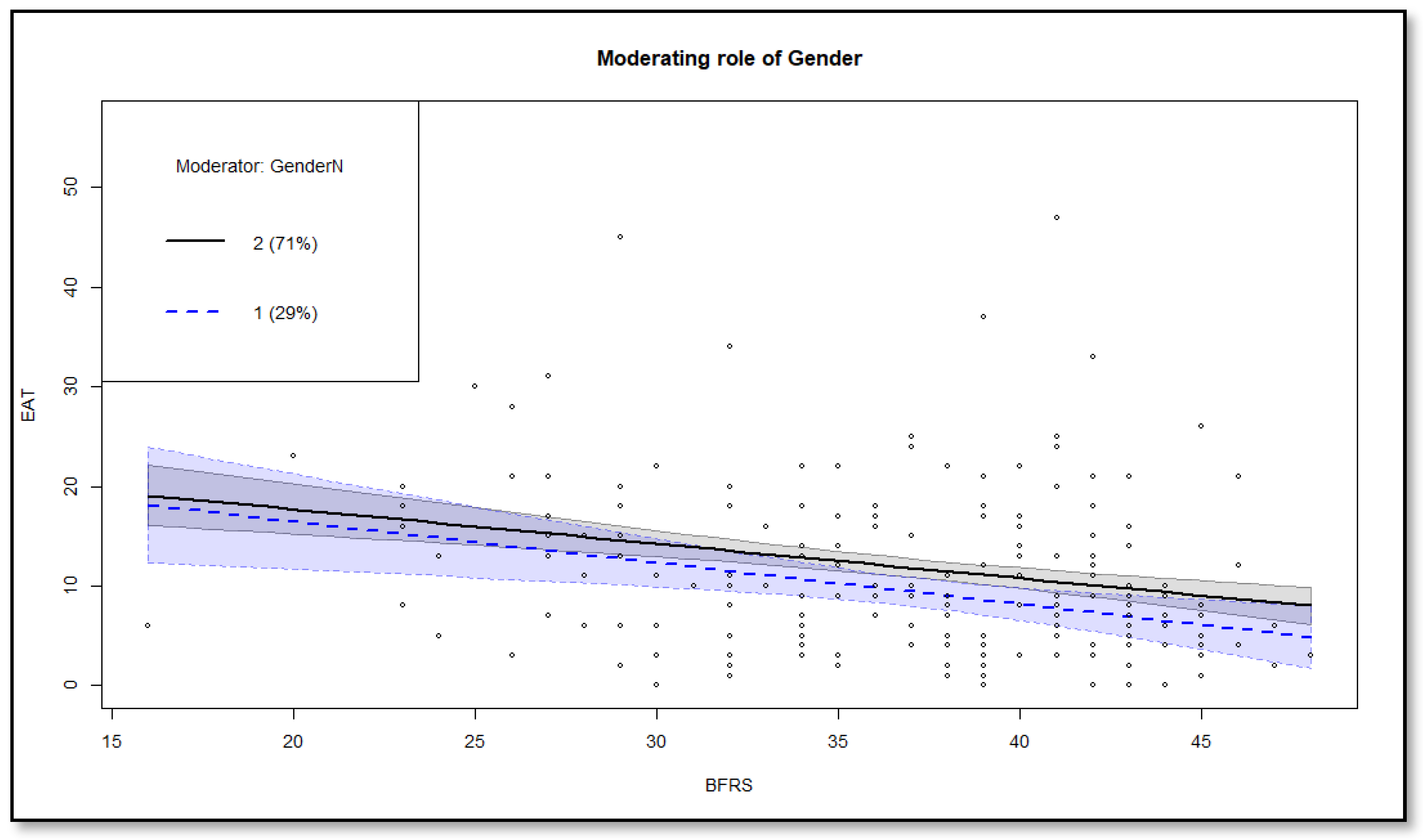

3.2. Testing the Moderated Mediation Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schaumberg, K.; Welch, E.; Breithaupt, L.; Hübel, C.; Baker, J.H.; Munn-Chernoff, M.A.; Yilmaz, Z.; Ehrlich, S.; Mustelin, L.; Ghaderi, A.; et al. The Science Behind the Academy for Eating Disorders’ Nine Truths About Eating Disorders. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2017, 25, 432–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, D.M. Measurement of eating disorder psychopathology. In Eating Disorders and Obesity; Fairburn, C.G., Brownell, K.D., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Eating Disorders. Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa and Related Eating Disorders; British Psychological Society (UK): Leicester UK, 2004; ISBN 0013-7006. [Google Scholar]

- Lock, J.; Le Grange, D. Family-based treatment of eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2005, 37, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesare, C.; Francesco, P.; Valentino, Z.; Barbara, D.; Olivia, R.; Gianluca, C.; Patrizia, T.; Enrico, M. Shame proneness and eating disorders: A comparison between clinical and non-clinical samples. Eat. Weight Disord. 2016, 21, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindvall Dahlgren, C.; Wisting, L.; Rø, Ø. Feeding and eating disorders in the DSM-5 era: A systematic review of prevalence rates in non-clinical male and female samples. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Garcia, M.; Gutierrez-Maldonado, J.; Treasure, J.; Vilalta-Abella, F. Craving for Food in Virtual Reality Scenarios in Non-Clinical Sample: Analysis of its Relationship with Body Mass Index and Eating Disorder Symptoms. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2015, 23, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillipou, A.; Meyer, D.; Neill, E.; Tan, E.J.; Toh, W.L.; Van Rheenen, T.E.; Rossell, S.L. Eating and exercise behaviors in eating disorders and the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: Initial results from the COLLATE project. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 1158–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignon, A.; Beardsmore, A.; Spain, S.; Kuan, A. “Why i won’t eat”: Patient testimony from 15 anorexics concerning the causes of their disorder. J. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 942–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.; Nicklett, E.J.; Roeder, K.; Kirz, N.E. Eating disorder symptoms among college students: Prevalence, persistence, correlates, and treatment-seeking. J. Am. Coll. Health 2011, 59, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhu, Y.; Jin, H.; Zhang, H.; Wan, Y.; Li, C.; Yu, D. An update on the prevalence of eating disorders in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat. Weight Disord. 2022, 27, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, N.; Waller, G.; Thomas, G. Core beliefs in anorexic and bulimic women. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1999, 187, 736–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, G.; Ohanian, V.; Meyer, C.; Osman, S. Cognitive content among bulimic women: The role of core beliefs. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2000, 28, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawed, A.; Harrison, A.; Dimitriou, D. The Presentation of Eating Disorders in Saudi Arabia. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 586706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Azeem Taha, A.A.; Abu-Zaid, H.A.; El-Sayed Desouky, D. Eating Disorders Among Female Students of Taif University, Saudi Arabia. Arch. Iran. Med. 2018, 21, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Mehak, A.; Racine, S.E. ‘Feeling fat’ is associated with specific eating disorder symptom dimensions in young men and women. Eat. Weight Disord. 2021, 26, 2345–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivière, J.; Douilliez, C. Perfectionism, rumination, and gender are related to symptoms of eating disorders: A moderated mediation model. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2017, 116, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Ross, D.; Ross, S.A. Imitation of film-mediated aggressive models. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1963, 66, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, J. Psychological Treatment of Food Refusal in Young Children. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2002, 7, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annus, A.M.; Smith, G.T.; Fischer, S.; Hendricks, M.; Williams, S.F. Associations among Family-of-Origin Food-Related Experiences, Expectancies, and Disordered Eating. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2007, 40, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, K.M.; Rodin, J. Mothers, Daughters, and Disordered Eating. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1991, 100, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.; Hume-Wright, A. Lay theories of anorexia nervosa. J. Clin. Psychol. 1992, 48, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.C.; Pruitt, J.A.; Mann, L.M.L.; Thelen, M.H. Attitudes and knowledge regarding bulimia and anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1986, 5, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haworth-Hoeppner, S. The critical shapes of body image: The role of culture and family in the production of eating disorders. J. Marriage Fam. 2000, 62, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, S.; Vieira, A.I.; Rodrigues, T.; Machado, P.P.; Brandão, I.; Timóteo, S.; Nunes, P.; Machado, B. Adult attachment in eating disorders mediates the association between perceived invalidating childhood environments and eating psychopathology. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 5478–5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtom-Viesel, A.; Allan, S. A systematic review of the literature on family functioning across all eating disorder diagnoses in comparison to control families. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 34, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon-Daly, J.; Serpell, L. Protective factors against disordered eating in family systems: A systematic review of research. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrow, S.M.; Accurso, E.C.; Nauman, E.R.; Goldschmidt, A.B.; Le Grange, D. Exploring Types of Family Environments in Youth with Eating Disorders. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2017, 25, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jewell, T.; Blessitt, E.; Stewart, C.; Simic, M.; Eisler, I. Family Therapy for Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders: A Critical Review. Fam. Process 2016, 55, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienecke, R. Family-based treatment of eating disorders in adolescents: Current insights. Adolesc. Health. Med. Ther. 2017, 8, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holston, J.I.; Cashwell, C.S. Assesment of family functioning and eating disorders—The mediating role of self-esteem. J. Coll. Couns. 2000, 3, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Leung, N.; Harris, G. Dysfunctional core beliefs in eating disorders: A review. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2007, 21, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatoum, A.H.; Burton, A.L.; Abbott, M.J. Assessing negative core beliefs in eating disorders: Revision of the Eating Disorder Core Beliefs Questionnaire. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Welch, S.L.; Doll, H.A.; Davies, B.A.; O’Connor, M.E. Risk Factors for Bulimia Nervosa A Community-Based Case-Control Study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1997, 54, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padesky, C.A.; Greenberger, D. Clinician’s Guide to Mind over Mood; Guilford Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1995; ISBN 9780898628210. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, M.J.; Todd, G.; Wells, A. Bulimia Nervosa: A Client’s Guide to Cognitive Therapy; Jessica Kingsley: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, M.J.; Wells, A.; Todd, G. A cognitive model of bulimia nervosa. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 43, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, M.J.; Proudfoot, J. Positive core beliefs and their relationship to eating disorder symptoms in women. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2013, 21, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, M.J.; Todd, G.; Woolrich, R.; Somerville, K.; Wells, A. Assessing eating disorder thoughts and behaviors: The development and preliminary evaluation of two questionnaires. Cognit. Ther. Res. 2006, 30, 551–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, A.L.; Abbott, M.J. Processes and pathways to binge eating: Development of an integrated cognitive and behavioural model of binge eating. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiles Marcos, Y.; Quiles Sebastián, M.J.; Pamies Aubalat, L.; Botella Ausina, J.; Treasure, J. Peer and family influence in eating disorders: A meta-analysis. Eur. Psychiatry 2013, 28, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, V.; Davies, B. Clinical perfectionism and eating psychopathology in athletes: The role of gender. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2015, 74, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shingleton, R.M.; Thompson-Brenner, H.; Pratt, E.M.; Thompson, D.R.; Franko, D.L. Gender differences in clinical trials of binge eating disorder: An analysis of aggregated data. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 83, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D.M.; Bohr, Y.; Garfinkel, P.E. The Eating Attitudes Test: Psychometric Features and Clinical Correlates. Psychol. Med. 1982, 12, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollon, S.D.; Kendall, P.C. Cognitive self-statements in depression: Development of an automatic thoughts questionnaire. Cognit. Ther. Res. 1980, 4, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fok, C.C.T.; Allen, J.; Henry, D.; Team, P.A. The Brief Family Relationship Scale: A Brief Measure of the Relationship Dimension in Family Functioning. Assessment 2014, 21, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Subaie, A.; Al-Shammari, S.; Bamgboye, E.; Al-Sabhan, K.; Al-Shehri, S.; Bannah, A.R. Validity of the Arabic version of the Eating Attitude Test. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1996, 20, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, F.; Yunibhand, J.; Sukratul, S. Relationship between personal, maternal, and familial factors with mental health problems in school-aged children in Aceh province, Indonesia. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2017, 25, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rstudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R; RStudio, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Revelle, W. Using the Psych Package to Generate and Test Structural Models. 2017. Available online: https://www.personality-project.org/r/psych_for_sem.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Kroplewski, Z.; Szcześniak, M.; Furmańska, J.; Gójska, A. Assessment of family functioning and eating disorders—The mediating role of self-esteem. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leys, C.; Kotsou, I.; Goemanne, M.; Fossion, P. The Influence of Family Dynamics On Eating Disorders and Their Consequence On Resilience: A Mediation Model. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2017, 45, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loth, K.A.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Croll, J.K. Informing family approaches to eating disorder prevention: Perspectives of those who have been there. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2009, 42, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erriu, M.; Cimino, S.; Cerniglia, L. The role of family relationships in eating disorders in adolescents: A narrative review. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.P.; Sadeh-Sharvit, S. Preventing eating disorders and disordered eating in genetically vulnerable, high-risk families. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 56, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.G.; Cohen, P.; Kasen, S.; Brook, J.S. Childhood adversities associated with risk for eating disorders or weight problems during adolescence or early adulthood. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoebridge, P.; Gowers, S.G. Parental high concern and adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa: A case-control study to investigate direction of causality. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000, 176, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluck, A.S. Family factors in the development of disordered eating: Integrating dynamic and behavioral explanations. Eat. Behav. 2008, 9, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.J.; Leung, N.; Harris, G. Father-daughter relationship and eating psychopathology: The mediating role of core beliefs. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 45, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, H.M.; Rose, K.S.; Cooper, M.J. Parental bonding and eating disorder symptoms in adolescents: The meditating role of core beliefs. Eat. Behav. 2005, 6, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller, G.; Meyer, C.; Ohanian, V.; Elliott, P.; Dickson, C.; Sellings, J. The psychopathology of bulimic women who report childhood sexual abuse: The mediating role of core beliefs. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2001, 189, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller, G.; Kennerley, H.; Ohanian, V. Schema-Focused Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Eating Disorders. In Cognitive Schemas and Core Beliefs in Psychological Problems: A Scientist-Practitioner Guide; Riso, L.P., Du Toit, P.L., Stein, D.J., Young, J.E., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Worcester, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 139–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarychta, K.; Luszczynska, A.; Scholz, U. The association between automatic thoughts about eating, the actual-ideal weight discrepancies, and eating disorders symptoms: A longitudinal study in late adolescence. Eat. Weight Disord. 2014, 19, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, M.J.; Fairburn, C.G. Thoughts about eating, weight and shape in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Behav. Res. Ther. 1992, 30, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.J.; Todd, G.; Wells, A. Treating Bulimia Nervosa and Binge Eating: An Integrated Metacognitive and Cognitive Therapy Manual; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rikani, A.A.; Choudhry, Z.; Choudhry, A.M.; Ikram, H.; Asghar, M.W.; Kajal, D.; Waheed, A.; Mobassarah, N.J. A critique of the literature on etiology of eating disorders. Ann. Neurosci. 2013, 20, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stice, E. Sociocultural Influences on Body Image and Eating Disturbance. In Eating Disorders and Obesity; Fairburn, C.G., Brownell, K.D., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 0387307931. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, D.T.; Grilo, C.M.; Masheb, R.M. Gender differences in patients with binge eating disorder. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2002, 31, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautala, L.A.; Junnila, J.; Helenius, H.; Väänänen, A.M.; Liuksila, P.R.; Räihä, H.; Välimäki, M.; Saarijärvi, S. Towards understanding gender differences in disordered eating among adolescents. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 1803–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.B.; Bulik, C.M. Gender differences in compensatory behaviors, weight and shape salience, and drive for thinness. Eat. Behav. 2004, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Eating disorder symptoms | 11.2 | 8.66 | 1 | ||

| 2. Negative automatic thoughts | 65.15 | 25.90 | 0.34 *** | 1 | |

| 3. Family environment | 36.75 | 6.29 | −0.27 *** | −0.49 *** | 1 |

| Variable | Male | Female | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eating disorder symptoms | 9.32 (7.04) | 11.97 (9.15) | <0.001 |

| Family environment | 37.24 (5.49) | 36.54 (6.60) | 0.553 |

| Negative automatic thoughts | 67.78 (27.9) | 64.12 (25) | 0.318 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | β | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eating disorder symptoms | Intercept | 12.11 | 3.45 | 0.09 | <0.001 |

| Family environment | −0.49 | 0.17 | −11.90 | <0.001 | |

| Age | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.04 | 0.237 | |

| Body mass index | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.10 | <0.01 | |

| Self-rated health | −0.32 | 0.07 | −0.11 | <0.001 | |

| Negative automatic thoughts | Intercept | 16.48 | 4.12 | 10.11 | <0.001 |

| Family environment | −0.32 | 0.13 | −0.09 | <0.001 | |

| Age | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.326 | |

| Body mass index | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.11 | <0.05 | |

| Self-rated health | −0.13 | 0.05 | −0.10 | <0.01 | |

| Eating disorder symptoms | Intercept | 11.90 | 3.19 | 10.01 | <0.001 |

| Family environment | −0.18 | 0.07 | −0.09 | <0.001 | |

| Negative automatic thoughts | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.08 | <0.001 | |

| Age | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.432 | |

| Body mass index | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.05 | <0.05 | |

| Self-rated health | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.06 | <0.05 |

| Indirect Path | Coefficients | BootSE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family environment => negative automatic thoughts => eating disorder symptoms | −013 | 0.02 | [−0.18, −0.08] |

| Index of moderated mediation | 0.09 | 0.04 | [0.017, 0.180] |

| Direct Effects | Classification | Coefficients | BootSE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| family environment => eating disorder symptoms | Male | −0.14 | 0.13 | [−0.41, 0.13] |

| Female | −0.16 | 0.07 | [−0.31, −0.01] | |

| Indirect effects | ||||

| family environmen t=> negative automatic thoughts => eating disorder syptoms | Male | −0.18 | 0.03 | [−0.25, −0.11] |

| Female | −0.27 | 0.05 | [−0.39, −0.17] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alghanami, B.H.; El Keshky, M.E.S. The Relationship between the Family Environment and Eating Disorder Symptoms in a Saudi Non-Clinical Sample of Students: A Moderated Mediated Model of Automatic Thoughts and Gender. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 818. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100818

Alghanami BH, El Keshky MES. The Relationship between the Family Environment and Eating Disorder Symptoms in a Saudi Non-Clinical Sample of Students: A Moderated Mediated Model of Automatic Thoughts and Gender. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(10):818. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100818

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlghanami, Badra Hamdi, and Mogeda El Sayed El Keshky. 2023. "The Relationship between the Family Environment and Eating Disorder Symptoms in a Saudi Non-Clinical Sample of Students: A Moderated Mediated Model of Automatic Thoughts and Gender" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 10: 818. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100818

APA StyleAlghanami, B. H., & El Keshky, M. E. S. (2023). The Relationship between the Family Environment and Eating Disorder Symptoms in a Saudi Non-Clinical Sample of Students: A Moderated Mediated Model of Automatic Thoughts and Gender. Behavioral Sciences, 13(10), 818. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100818