The Mental Health Implications of Corporate Social Responsibility: The Significance of the Sense-Making Process and Prosocial Motivation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

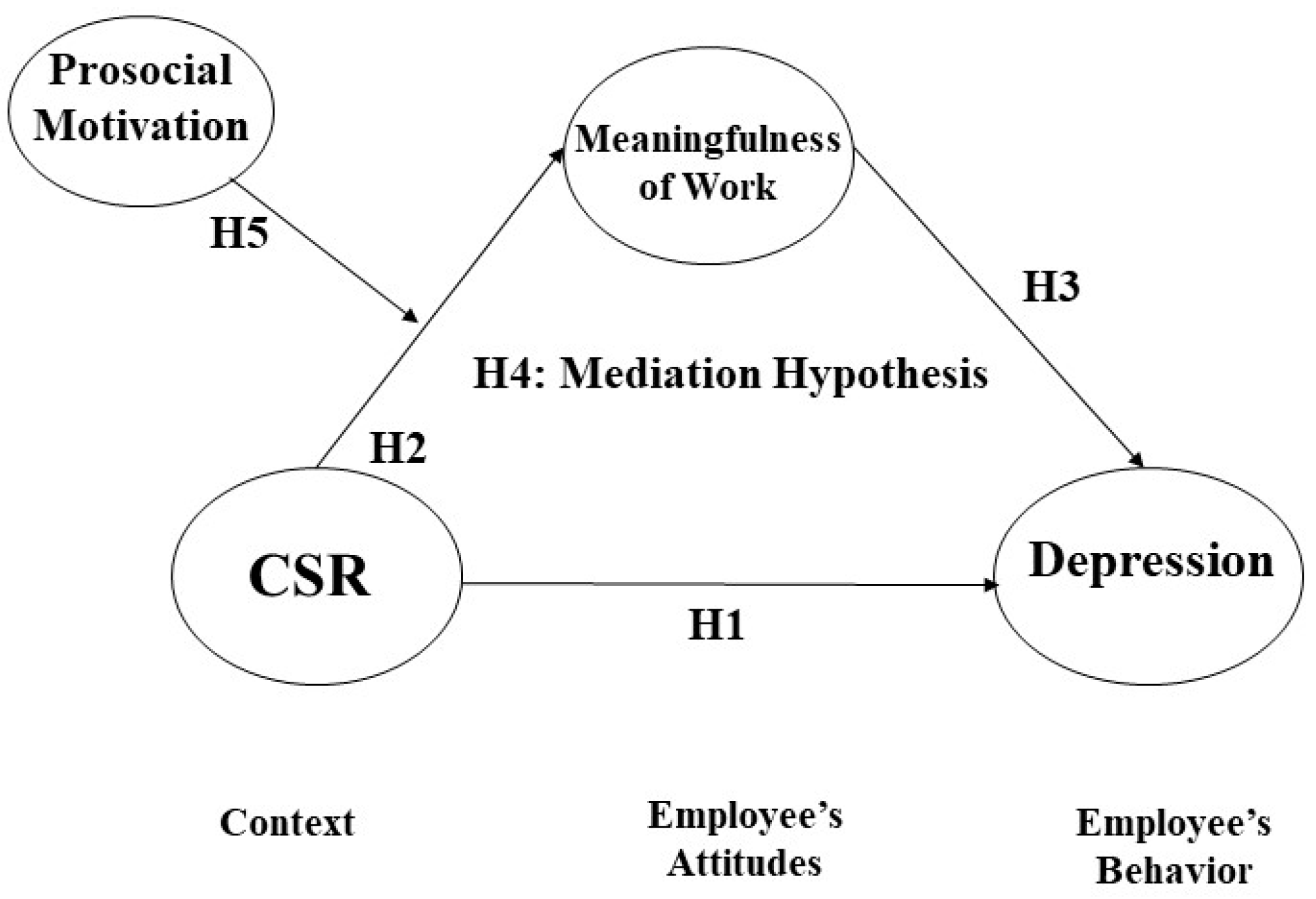

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. CSR and Depression

2.2. CSR and Meaningfulness of Work

2.3. Meaningfulness of Work and Depression

2.4. Mediating Effect of Meaningful Work in the CSR-Depression Link

2.5. Moderating Effect of Employee Prosocial Motivation in the Link between CSR and Meaningfulness of Work

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. CSR (Time Point 1, Collected from Employees)

3.2.2. Prosocial Motivation (Time Point 1, Collected from Employees)

3.2.3. Meaningfulness of Work (Time Point 2, Collected from Employees)

3.2.4. Depression (Time Point 3, Collected from Employees)

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Analytical Approach

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. Structural Model

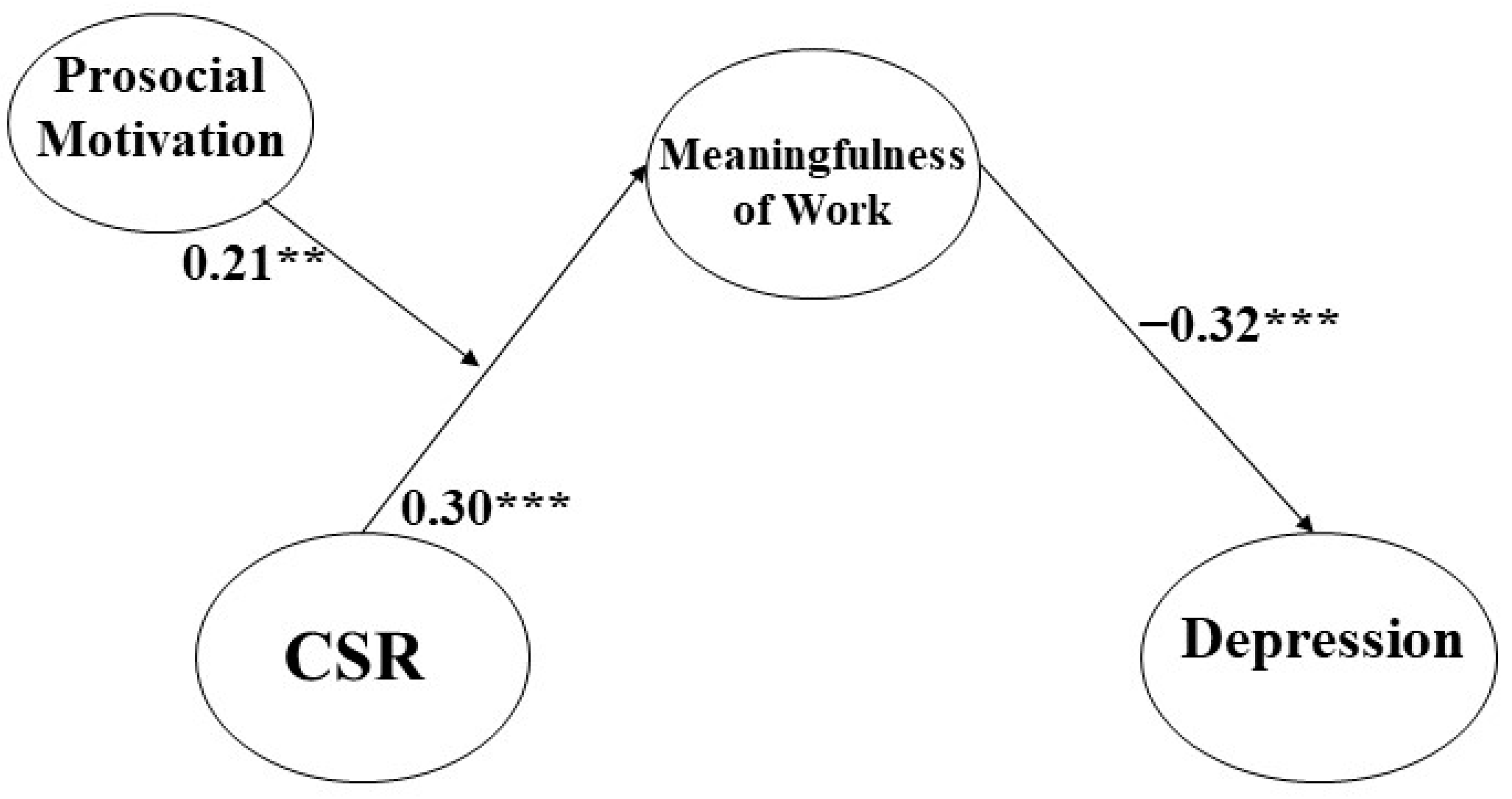

4.3.1. The Results of the Mediation Analysis

4.3.2. Bootstrapping

4.3.3. The Result of the Moderation Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Studies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguilera, R.V.; Rupp, D.E.; Williams, C.A.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the S Back in Corporate Social Responsibility: A Multilevel Theory of Social Change in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, T.; Elbanna, S. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) implementation: A review and a research agenda towards an integrative framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 183, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillan, S.L.; Koch, A.; Starks, L.T. Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. J. Corp. Fin. 2021, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The Contribution of Corporate Social Responsibility to Organizational Commitment. Inter. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Sofian, S.; Saeidi, P.; Saeidi, S.P.; Saaeidi, S.A. How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V. Consistency matters! How and when does corporate social responsibility affect employees’ organizational identification? J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 1141–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, J.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V.; Babu, N. The Psychological Microfoundations of Corporate Social Responsibility: A Person-centric Systematic Review. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A.; Newman, A.; Shao, R.; Cooke, F.L. Advances in employee-focused micro-level research on corporate social responsibility: Situating new contributions within the current state of the literature. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Mallory, D.B. Corporate social responsibility: Psychological, person-centric, and progressing. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, P. Meta-analyses on corporate social responsibility (CSR): A literature review. Manag. Rev. Quar. 2021, 72, 627–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, D.A.; McLaughlin, T.J.; Rogers, W.H.; Chang, H.; Lapitsky, L.; Lerner, D. Job performance deficits due to depression. Am. J. Psychi. 2006, 163, 1569–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birnbaum, H.G.; Kessler, R.C.; Kelley, D.; Ben-Hamadi, R.; Joish, V.N.; Greenberg, P.E. Employer burden of mild, moderate, and severe major depressive disorder: Mental health services utilization and costs, and work performance. Depre. Anx. 2010, 27, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.J.; Baase, C.M.; Sharda, C.E.; Ozminkowski, R.J.; Nicholson, S.; Billotti, G.M.; Turpin, R.S.; Olson, M.; Berger, M.L. The assessment of chronic health conditions on work performance, absence, and total economic impact for employers. J. Occu. Environ. Medic. 2005, 47, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans-Lacko, S.; Knapp, M. Global patterns of workplace productivity for people with depression: Absenteeism and presenteeism costs across eight diverse countries. Soc. Psychi. Psychiat. Epid. 2016, 51, 1525–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, N.C.; Newman, M.G. Anxiety and depression as bidirectional risk factors for one another: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 1155–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, D.; Henke, R.M. What does research tell us about depression, job performance, and work productivity? J. Occu. Environ. Medic. 2008, 50, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. On corporate social responsibility, sensemaking, and the search for meaningfulness through work. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 1057–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunderson, J.S.; Thompson, J.A. The Call of the Wild: Zookeepers, Callings, and the Double-Edged Sword of Deeply Meaningful Work. Adm. Sci. Q. 2009, 54, 32–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, B.D.; Dekas, K.H.; Wrzesniewski, A. On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Res. Org. Beh. 2010, 30, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.S.; Winn, B. Virtuousness in organizations. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship; OUP USA: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cardador, M.T.; Rupp, D.E. Organizational culture, multiple needs, and the meaningfulness of work. In The Handbook of Organizational Culture and Climate; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; p. 158175. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, M. Stress and depression in the employed population. Heal. Rep. 2006, 17, 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sowislo, J.F.; Orth, U. Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.J.; Kim, B.J. The performance implication of corporate social responsibility: The moderating role of employee’s prosocial motivation. Inter. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Heal. 2021, 18, 3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, R.D.; Patil, S.V. Proactivity despite discouraging supervisors: The powerful role of prosocial motivation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Sung, S.Y.; Choi, J.N.; Kim, M.S. Top management ethical leadership and firm performance: Mediating role of ethical and procedural justice climate. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 129, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.Y.; Tam, W.W.; Lu, Y.; Ho, C.S.; Zhang, M.W.; Ho, R.C. Prevalence of depression in the community from 30 countries between 1994 and 2014. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Ramos, M.A.; Torre, M.; Segal, J.B.; Peluso, M.J.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama 2016, 316, 2214–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, T.J.; Pevalin, D.J. Marital transitions and mental health. J. Heal. Soc. Beh. 2004, 45, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raikkonen, K.; Matthews, K.A.; Kuller, L.H. Depressive symptoms and stressful life events predict metabolic syndrome among middle-aged women: A comparison of World Health Organization, Adult Treatment Panel III, and International Diabetes Foundation definitions. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 872–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulsin, L.R.; Singal, B.M. Do depressive symptoms increase the risk for the onset of coronary disease? A systematic quantitative review. Psychosom. Medic 2003, 65, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Akiskal, H.S.; Ames, M.; Birnbaum, H.; Greenberg, P.; Hirschfeld, R.M.A.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Simon, G.E.; Wang, P.S. Prevalence and effects of mood disorders on work performance in a nationally representative sample of US workers. Am. J. Psychi. 2006, 163, 1561–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudêncio, P.; Coelho, A.; Ribeiro, N. The impact of CSR perceptions on workers turnover intentions: Exploring supervisor exchange process and the role of perceived external prestige. Soc. Res. J. 2020, 17, 543–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E.; Debebe, G. Interpersonal sensemaking and the meaning of work. Res. Org. Beh. 2003, 25, 93–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, C.W.; Skitka, L.J. Corporate Social Responsibility as a Source of Employee Satisfaction. Res. Org. Beh. 2012, 32, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Vohs, K.D. The Pursuit of Meaningfulness in Life. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; Volume 1, pp. 608–618. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A.M. Relational Job Design and the Motivation to make a Prosocial Difference. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M. Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liden, R.C. Making a difference in the teamwork: Linking team prosocial motivation to team processes and effectiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1102–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Hur, W.M. When do job-insecure employees keep performing well? The buffering roles of help and prosocial motivation in the relationship between job insecurity, work engagement, and job performance. J. Bus. Psychol. 2021, 36, 659–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatman, J.A. Improving interactional organizational research: A model of person-organization fit. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof, A.L. Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Johnson, E.C. Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis OF person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, R.N.; Behrend, T.S. An inconvenient truth: Arbitrary distinctions between organizational, Mechanical Turk, and other convenience samples. Indus. Org. Psychol. 2015, 8, 142–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Beh. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Sumanth, J.J. Mission possible? The performance of prosocially motivated employees depends on manager trustworthiness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; McCauley, C.; Rozin, P.; Schwartz, B. Jobs, Careers, and Callings: People’s Relations to their Work. J. Res. Pers. 1997, 31, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, E.M.; Malmgren, J.A.; Carter, W.B.; Patrick, D.L. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. Am. J. Prev. Medic. 1994, 10, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sage Focus Ed. 1993, 154, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brace, N.; Kemp, R.; Snelgar, R. SPSS for Psychologists: A Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS for Windows, 2nd ed.; Palgrave: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, J.S.; Shin, Y.; Choi, J.N.; Kim, M.S. How does corporate ethics contribute to firm financial performance? The role of collective organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 853–877. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, D.F.; Bernardi, R.A.; Neidermeyer, P.E.; Schmee, J. The effect of country and culture on perceptions of appropriate ethical actions prescribed by codes of conduct: A Western European perspective among accountants. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 70, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbeiss, S.A. Re-thinking ethical leadership: An interdisciplinary integrative approach. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.D.; Dunford, B.B.; Boss, A.D.; Boss, R.W.; Angermeier, I. Corporate social responsibility and the benefits of employee trust: A cross-disciplinary perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratianu, C.; Mocanu, R.; Stanescu, D.F.; Bejinaru, R. The Impact of Knowledge Hiding on Entrepreneurial Orientation: The Mediating Role of Factual Autonomy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratianu, C.; Stanescu, D.F.; Mocanu, R.; Bejinaru, R. Serial multiple mediation of the impact of customer knowledge management on sustainable product innovation by innovative work behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Percent |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 51.9% |

| Female | 48.1% |

| Age (years) | |

| 20–29 | 12.6% |

| 30–39 | 35.5% |

| 40–49 | 33.2% |

| 50–59 | 18.7% |

| Education | |

| Below high school | 8.4% |

| Community college | 16.8% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 62.1% |

| Master’s degree or higher | 12.6% |

| Occupation | |

| Office worker | 74.9% |

| Profession (Practitioner) | 7.7% |

| Production worker | 4.8% |

| Administrative positions | 4.8% |

| Public official | 3.9% |

| Sales and Service | 2.9% |

| Education | 0.5% |

| Freelance | 0.5% |

| Position | |

| Staff | 22.0% |

| Assistant Manager | 18.7% |

| Manager or deputy general manager | 35.5% |

| Department/general manager or director and above | 23.8% |

| Tenure (years) | |

| Below 5 | 45.8% |

| 5–10 | 27.6% |

| 11–15 | 14.9% |

| 16–20 | 5.2% |

| 21–25 | 2.8% |

| Above 26 | 3.7% |

| Industry Type | |

| Manufacturing | 24.6% |

| Construction | 14.0% |

| Wholesale/Retail business | 12.1% |

| Health and welfare | 10.1% |

| Information service and telecommunications | 9.7% |

| Services | 10.1% |

| Education | 6.7% |

| Financial/insurance | 3.4% |

| Consulting and advertising Others | 0.5% |

| Others | 8.7% |

| Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender_T2 | 1.47 | 0.50 | - | ||||||

| 2. Education_T2 | 2.73 | 0.79 | −0.20 ** | - | |||||

| 3. Tenure_T2 | 7.91 | 7.57 | −0.31 ** | −0.01 | - | ||||

| 4. Position_T2 | 3.04 | 1.62 | −0.47 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.31 ** | - | |||

| 5. CSR_T1 | 3.20 | 0.62 | −0.16 * | 0.001 | 0.19 ** | 0.10 | - | ||

| 6. PM_T1 | 3.22 | 0.59 | −0.11 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.17 * | 0.29 ** | - | |

| 7. MoW_T2 | 3.24 | 0.59 | −0.20 ** | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.32 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.35 ** | - |

| 8. Dep_T3 | 3.71 | 0.56 | 0.05 | −0.07 | −0.13 | −0.07 | −0.17 * | −0.05 | −0.30 ** |

| Hypothesis | Path (Relationship) | Unstandardized Estimate | SE | Standardized Estimate | Supported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CSR -> Depression | −0.005 | 0.059 | −0.008 | No |

| 2 | CSR -> Meaningfulness of Work | 0.267 | 0.072 | 0.300 *** | Yes |

| 3 | Meaningfulness of Work -> Depression | −0.249 | 0.064 | −0.320 *** | Yes |

| 5 | CSR × Prosocial Motivation | 0.389 | 0.123 | 0.212 ** | Yes |

| Model (Hypothesis 4) | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSR → POS → Organizational Commitment → Knowledge-sharing Behavior | 0.229 | 0.047 | 0.277 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, B.-J.; Kim, M.-J.; Lee, D.-g. The Mental Health Implications of Corporate Social Responsibility: The Significance of the Sense-Making Process and Prosocial Motivation. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 870. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100870

Kim B-J, Kim M-J, Lee D-g. The Mental Health Implications of Corporate Social Responsibility: The Significance of the Sense-Making Process and Prosocial Motivation. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(10):870. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100870

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Byung-Jik, Min-Jik Kim, and Dong-gwi Lee. 2023. "The Mental Health Implications of Corporate Social Responsibility: The Significance of the Sense-Making Process and Prosocial Motivation" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 10: 870. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100870

APA StyleKim, B.-J., Kim, M.-J., & Lee, D.-g. (2023). The Mental Health Implications of Corporate Social Responsibility: The Significance of the Sense-Making Process and Prosocial Motivation. Behavioral Sciences, 13(10), 870. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100870