When the Going Gets Challenging—Motivational Theories as a Driver for Workplace Health Promotion, Employees Well-Being and Quality of Life

Abstract

:1. Introduction

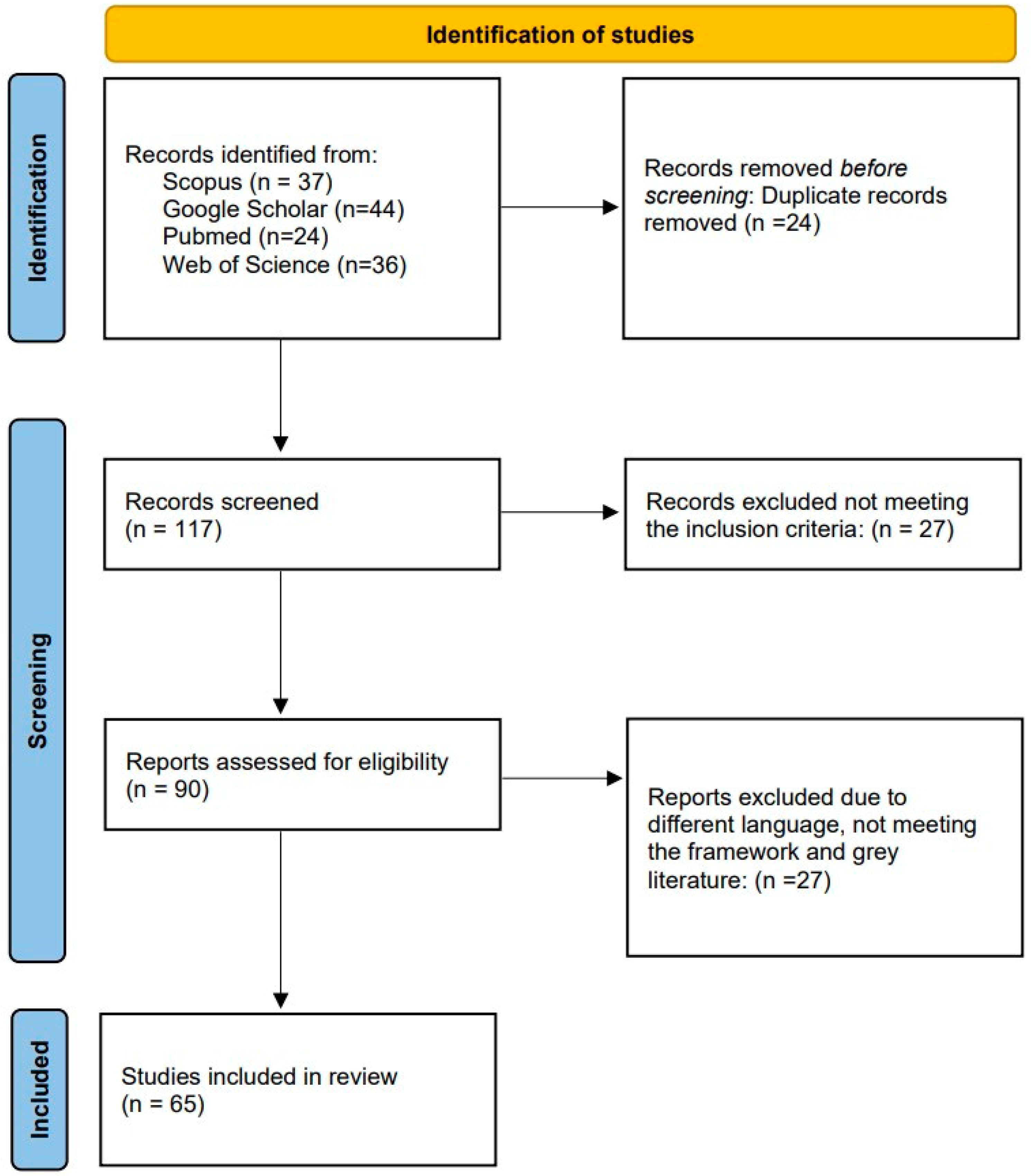

2. Material and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Motivation in General Psychology

3.1.1. Hedonism

3.1.2. Instincts

3.1.3. Drive Reduction Theory

3.1.4. Arousal Approaches

3.1.5. Cognitive Approaches

3.2. Motivation in Work Psychology

3.2.1. Content Theories

- Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory;

- Alderfer’s modified need hierarchy model;

- Herzberg’s two-factor theory;

- McClelland’s achievement motivation theory.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory

Alderfer’s Modified Need Hierarchy Model

Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory

McClelland’s Achievement Motivation Theory

- Achievement motive (n-ach)

- Authority/power motive (n-pow)

- Affiliation motive (n-affil)

3.2.2. Process Theories

- Expectancy-based models: Vroom and Porter and Lawler;

- Equity theory: Adams;

- Goal theory: Locke;

- Attribution theory: Heider and Kelley.

Expectancy-Based Models: Vroom and Porter and Lawler

Equity Theory: Adams

Goal Theory: Locke

Attribution Theory: Heider and Kelley

4. Discussion

4.1. Conclusions

4.2. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jodai, H.; Zafarghandi, M.V. Motivation, Integrativeness, Organizational Influence, Anxiety, and English Achievement: Evidence from a Military University. Glottotheory 2013, 4, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kispál-Vitai, Z. Comparative analysis of motivation theories. Int. J. Eng. Manag. Sci. 2016, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steers, R.M.; Mowday, R.T.; Shapiro, D.L. The future of work motivation theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenćić-Kampl, K.; Kampl, B.; Susić, V. Survey about the motivation for the study of veterinary medicine in Croatia. DTW Dtsch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 1996, 103, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hansez, I.; Schins, F.; Rollin, F. Occupational stress, work-home interference and burnout among Belgian veterinary practitioners. Ir. Vet. J. 2008, 61, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkin, T.; Brown, J.; Macdonald, E. Occupational risks of working with horses: A questionnaire survey of equine veterinary surgeons. Equine Vet. Educ. 2018, 30, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartram, D.J.; Sinclair, J.M.; Baldwin, D.S. Interventions with potential to improve the mental health and well-being of UK veterinary surgeons. Vet. Rec. 2010, 166, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartram, D.J.; Baldwin, D.S. Veterinary surgeons and suicide: A structured review of possible influences on increased risk. Vet. Rec. 2010, 166, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.V. Psychology of Motivation; Nova Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Young, P.T. Psychological hedonism. In Motivation of Behavior: The Fundamental Determinants of Human and Animal Activity; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1936; pp. 318–387. [Google Scholar]

- McAllister, W. Toward a re-examination of psychological hedonism. Philos. Phenomenol. Res. 1953, 13, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garson, J. Two types of psychological hedonism. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. Part C Stud. Hist. Philos. Biol. Biomed. Sci. 2016, 56, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.M. Psychological hedonism, hedonic motivation, and health behavior. In Affective Determinants of Health Behavior; Oxford Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. 204. [Google Scholar]

- Vroom, V.H. Work and Motivation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- McDougall, W. The gregarious instinct. In An Introduction to Social Psychology; Methuen: London, UK, 1908. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, P. Instinct Theory of Motivation. Psychestudy. 2017. Available online: https://www.psychestudy.com/general/motivation-emotion/instinct-theory-motivation (accessed on 4 June 2022).

- Hull, C.L. Principles of Behavior: An Introduction to Behavior Theory; Appleton-Century-Crofts: New York, NY, USA, 1943. [Google Scholar]

- Wolpe, J. Need-reduction, drive-reduction, and reinforcement: A neurophysiological view. Psychol. Rev. 1950, 57, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seward, J.P. Drive, incentive, and reinforcement. Psychol. Rev. 1956, 63, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganta, V.C. Motivation in the workplace to improve the employee performance. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. Appl. Sci. 2014, 2, 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Stennett, R.G. The relationship of performance level to level of arousal. J. Exp. Psychol. 1957, 54, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisenzein, R. Pleasure-arousal theory and the intensity of emotions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckhausen, H. The Anatomy of Achievement Motivation; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, P. Arousal Theory of Motivation. Psychestudy. 2017. Available online: https://www.psychestudy.com/general/motivation-emotion/arousal-theory-motivation (accessed on 4 June 2022).

- Yerkes, R.M.; Dodson, J.D. The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. Punishment: Issues and experiments. J. Comp. Neurol. Psychol. 1908, 18, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolman, E.C. A cognition motivation model. Psychol. Rev. 1952, 59, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J. Cognitive development in children: Piaget. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1964, 2, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermer, J. The interrelationship of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Acad. Manag. J. 1975, 18, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinder, C.C. Work Motivation in Organizational Behavior; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kuvaas, B.; Buch, R.; Weibel, A.; Dysvik, A.; Nerstad, C.G. Do intrinsic and extrinsic motivation relate differently to employee outcomes? J. Econ. Psychol. 2017, 61, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A. How does intrinsic and extrinsic motivation drive performance culture in organizations? Cogent Educ. 2017, 4, 1337543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legault, L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.A., Jr. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, R. Stress in Surgeons. Stress in Health Professionals; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1987; pp. 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Survey details stress factors that influence Australian vets. Aust. Vet. J. 2002, 80, 522–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, C.J.; Cooper, C.L. Occupational stress and health: Some current issues. In International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Cooper, C.L., Robertson, R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R. Psychological Stress in the Workplace. In Occupational Stress: A Handbook; Crandall, R., Perrewe, P.L., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nyssen, A.S.; Hansez, I.; Baele, P.; Lamy, M.; De Keyser, V. Occupational stress and burnout in anaesthesia. Br. J. Anaesth. 2003, 90, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, D.C. Credentialed veterinary technician intrinsic and extrinsic rewards: A narrative review. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2022, 260, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynia, M.K. The Risks of Rewards in Health Care: How Pay-for-Performance Could Threaten, or Bolster, Medical Professionalism; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 884–887. [Google Scholar]

- Iglehart, J.K. Expanding the role of advanced nurse practitioners—Risks and rewards. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.C.; Dill, J.; Kalleberg, A.L. The quality of healthcare jobs: Can intrinsic rewards compensate for low extrinsic rewards? Work. Employ. Soc. 2013, 27, 802–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganster, D.C.; Kiersch, C.E.; Marsh, R.E.; Bowen, A. Performance-based rewards and work stress. In Integrating Organizational Behavior Management with Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013; pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, J.; Hoole, C. The influence of organisational rewards on workplace trust and work engagement. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiffin, J.; McCormick, E.J. Industrial Psychology; George Allen and Unwin: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, L.J. Management and Organisational Behaviour; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dinibutun, S.R. Work motivation: Theoretical framework. J. GSTF Bus. Rev. 2012, 1, 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A. Motivation and Personality; Harpers: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, B. A Summary of Motivation Theories. 2012. Available online: https://studylib.net/doc/8112742/a-summary-of-motivation-theories-by-benjamin-ball (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Mangi, A.A.; Kanasro, H.A.; Burdi, M.B. Motivation tools and organizational success: A criticle analysis of motivational theories. Gov.-Annu. Res. J. Political Sci. 2015, 4, 51–62. Available online: https://sujo.usindh.edu.pk/index.php/THE-GOVERNMENT (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Alderfer, C.P. Existence, Relatedness, and Growth: Human Needs in Organizational Settings; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Stello, C.M. Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory of Job Satisfaction: An Integrative Literature Review. In The 2011 Student Research Conference: Exploring Opportunities in Research, Policy, and Practice; University of Minnesota, Department of Organizational Leadership, Policy and Development: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2011; pp. 119–138. [Google Scholar]

- Alshmemri, M.; Shahwan-Akl, L.; Maude, P. Herzberg’s two-factor theory. Life Sci. J. 2017, 14, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg, F.I. Work and the Nature of Man; World Pub. Co.: Cleveland, OH, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Kacel, B.; Miller, M.; Norris, D. Measurement of nurse practitioner job satisfaction in a Midwestern state. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2005, 17, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lephalala, R.P. Factors Influencing Nursing Turnover in Selected Private Hospitals in England. Master’s Thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J.E. Job Satisfaction and Burnout among Foreign-Trained Nurses in Saudi Arabia: A Mixed-Method Study. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, D.C.; Mac Clelland, D.C. Achieving Society; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Pardee, R.L. Motivation Theories of Maslow, Herzberg, McGregor & McClelland. A Literature Review of Selected Theories Dealing with Job Satisfaction and Motivation; Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC): Washington, DC, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Osemeke, M.; Adegboyega, S. Critical review and comparism between Maslow, Herzberg and McClellands theory of needs. Funai J. Account. Bus. Finance 2017, 1, 161–173. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, L.W.; Lawler, E.E. Managerial Attitudes and Performance; Richard D. Irwin, Inc.: Homewood, IL, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Slocum, J.W.; Hellriegel, D. Principles of Organizational Behavior; South-Western/Cengage Learning: Mason, OH, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, J.S. Towards an understanding of inequity. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1963, 67, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dierendonck, D.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Sixma, H.J. Burnout among general practitioners: A perspective from equity theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1994, 13, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. Toward a theory of task motivation and incentives. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1968, 3, 157–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibipour, B.; Vanaki, Z.; Hadjizadeh, E. The effect of implementing “Goal Setting Theory” by nurse managers on staff nurses’ job motivation. Iran J. Nurs. 2009, 22, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, J. HEIDER. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations (Book Review). Soc. Forces 1958, 37, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, H.H. The processes of causal attribution. Am. Psychol. 1973, 28, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. Reflections on the history of attribution theory and research: People, personalities, publications, problems. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 39, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. Social Motivation and Moral Emotions’: Attribution Theory in the Organizational Sciences. Theoretical and Empirical Contributions; Martinko, M.J., Ed.; Academy of Management: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2004; pp. 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Alrawahi, S.; Sellgren, S.F.; Alwahaibi, N.; Altouby, S.; Brommels, M. Factors affecting job satisfaction among medical laboratory technologists in University Hospital, Oman: An exploratory study. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2019, 34, e763–e775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|

| Types of studies | English and German language only |

| Worldwide studies | |

| Publication date 1930–2020 | |

| Observational studies, mixed studies, empirical studies, review articles, and theoretical articles | |

| Peer reviewed journal papers Chapters with an abstract | |

| Types of participants | Practicing and retired human and veterinary health care employees including students and junior trainees and specialists. Employees of other professions to compare the health care sector to other professions |

| Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|

| Types of studies | Non-English/non-German language |

| Proceedings | |

| Publication date before 1930 or after 2020 | |

| Duplicates Editorials Letters Commentary Press release Grey literature | |

| Types of participants | Regarding the articles investigating health care settings: non-practicing human and veterinary health care employees e.g., laboratory staff |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coco, L.K.; Heidler, P.; Fischer, H.A.; Albanese, V.; Marzo, R.R.; Kozon, V. When the Going Gets Challenging—Motivational Theories as a Driver for Workplace Health Promotion, Employees Well-Being and Quality of Life. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 898. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110898

Coco LK, Heidler P, Fischer HA, Albanese V, Marzo RR, Kozon V. When the Going Gets Challenging—Motivational Theories as a Driver for Workplace Health Promotion, Employees Well-Being and Quality of Life. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(11):898. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110898

Chicago/Turabian StyleCoco, Lisa Karolin, Petra Heidler, Holger Adam Fischer, Valeria Albanese, Roy Rillera Marzo, and Vlastimil Kozon. 2023. "When the Going Gets Challenging—Motivational Theories as a Driver for Workplace Health Promotion, Employees Well-Being and Quality of Life" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 11: 898. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110898

APA StyleCoco, L. K., Heidler, P., Fischer, H. A., Albanese, V., Marzo, R. R., & Kozon, V. (2023). When the Going Gets Challenging—Motivational Theories as a Driver for Workplace Health Promotion, Employees Well-Being and Quality of Life. Behavioral Sciences, 13(11), 898. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110898