Coaches’ Mind Games: Harnessing Technical Fouls for Psychological Momentum in Basketball

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Psychological Momentum in Sports

1.2. Psychological Momentum in Basketball

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Content Analysis

2.4. Quality Assurance

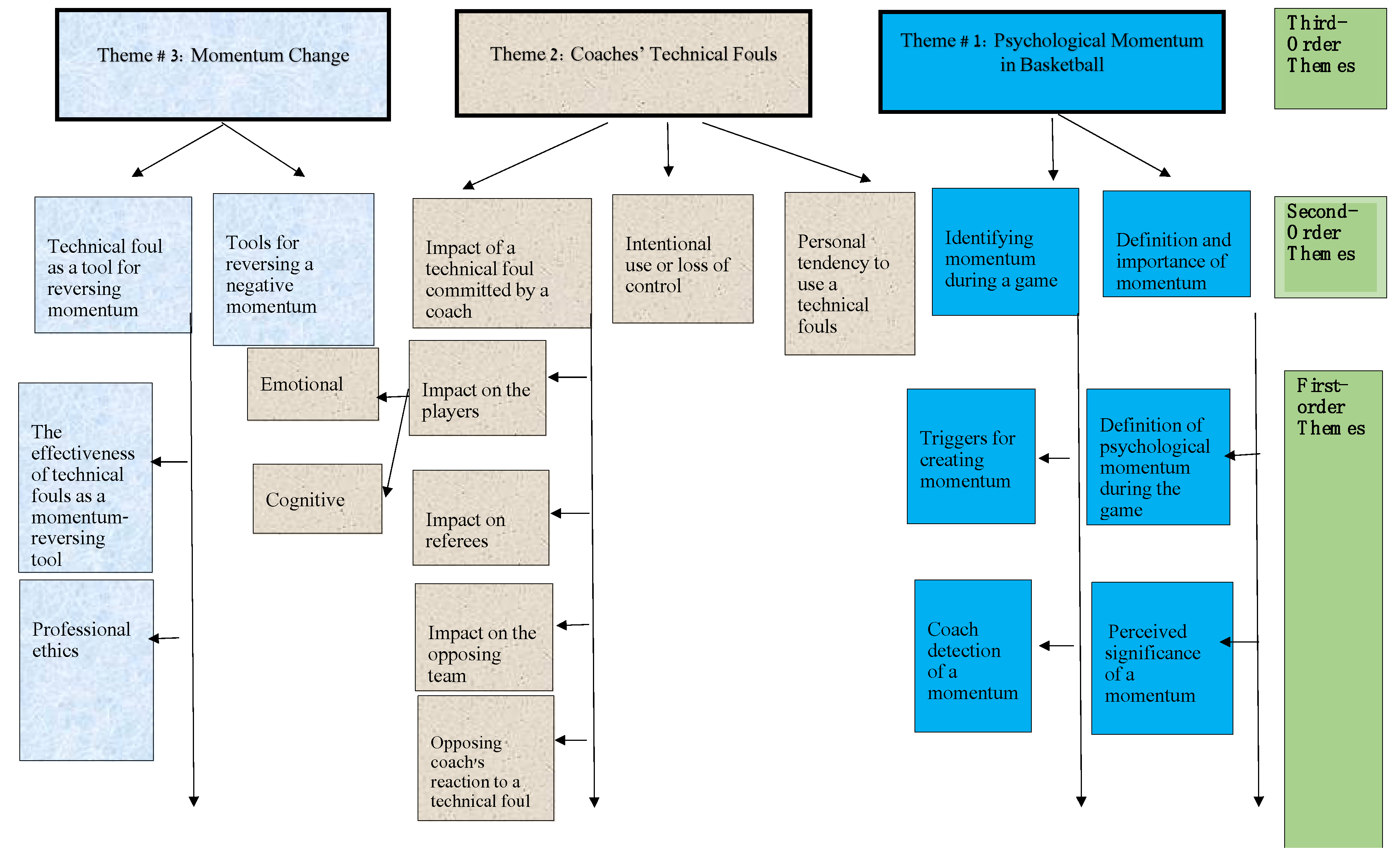

3. Results

3.1. Theme #1. Psychological Momentum in Basketball

3.1.1. Definition and Importance of Momentum

- (1)

- Definition of Psychological Momentum during the Game

“A good action or a collection of good actions by an individual or the team, bringing about a peak of enthusiasm and confidence.”

“You feel a sudden increase in confidence, adrenaline, enthusiasm, and usually, an enhanced level of performance.”

“In a series of positive activities, in defense or offense, the players believe in the coach and his/her work with them, creating a process of momentum in the game.”

“It’s a sequence of decisions and actions that are not always recorded by statistics. I feel it’s one of the most meaningful events in the game and a motivating factor for the team, which builds some momentum. Another element is team coordination; you see a team that is psyched in a good, defensive way—a kind of ecstasy, reaching a phenomenal level of enthusiasm.”

- (2)

- Perceived Significance of a Momentum

“How vital is psychological momentum during a game? It’s like asking how important it is to breathe (laughing).”

“The most dominant characteristic of the game is changing momentum. It’s most likely that the team that succeeds in generating momentum and maintaining it over time, and is the fastest in stopping negative momentum, is the better team.”

3.1.2. Identifying Momentum during a Game

- (1)

- Triggers for Creating Momentum

“Triggers are turning one mistake into two mistakes... meaning that we missed a layup and, out of frustration, committed an unsportsmanlike foul on the way to defense; usually, the second and third actions produce the negative momentum”.

“It could be a stop in the lane, a charge, a big rebound, a big steal. In offensive situations, we talk about a big basket, a big pass, a changed outcome, a change in the situation where you were chasing a team, and suddenly you shoot a basket, and finally you lead”.

- (2)

- Coach Detection of a Momentum

“Recognizing momentum comes first, and then you can make some tactical moves, and like everything else, sometimes it goes great, and sometimes you see it’s not helpful”.

“I feel it in the players’ vulnerable moments—in small crises, when someone fails to return to defense or fails to close the base-line. Simple elements that you can examine and observe. If you observe these, the crisis [will be] small”.

“Body language and speech. The players’ behavior toward each other, toward you. Many more positive things. When there is no momentum and you replace a player, the one who is replaced is always dissatisfied, which makes sense, but when momentum is positive the players understand that that’s how the system works, so it’s much easier for them to accept things”.

“Body language gives us a lot. Counting the ‘high-fives’ exchanged by the players is a common sign”.

3.2. Theme #2. Coaches’ TFs

3.2.1. Personal Tendency to Use a TF

“I’m not a big fan of TFs. I’m always more concerned about their consequences because while I may have gained a momentum change, how my players perceive me is also important; legitimacy is essential. I realize TFs can help change momentum, but they may give my players permission to lose their tempers or talk inappropriately to the referees”.

“I’m not the type of person who tries to get a TF to change the momentum in a game; I don’t believe in that. And I would certainly not do that at the high levels”.

“We have a positive attitude (toward the game), we have passion and fun. That’s what I believe in, and that’s the spirit we discussed—the positive spirit and the positive psychological mindset we need to create. I don’t get many TFs because I’m also on good terms with the referees”.

3.2.2. Intentional Use or Loss of Control

“20% of coaches’ TFs are outbursts, while 80% are under control. Some coaches have an inherent agenda to badger the referees”.

“The coach knows he’s getting a TF, he knows what he’ll gain from it. The question is, when you get a TF—is it your ball or the opposing team’s? It’s an art”.

“I can say that I lost control very few times. I often turn to my assistant and say ‘Everything is under control, don’t worry’. I received TFs, but none occurred because of a lack of control”.

3.2.3. Impact of a TF Committed by a Coach

- (1)

- Impact on the Players

“What works for player A will not work for player B, and what works for player A on a certain day will not always work for him on another day. Thus, TFs depend greatly on the situation, and I can’t define them”.

- Emotional

“It produces a change in the energy of the team. Say we count on a scale of 1 to 10, and the energy was a 5—it will move to either an 8 or a 2, depending on the players. Some may break and feel shaken up if it’s something they’re used to having relatively in control”.

“You evaluate the situation and see that some players are somewhat apathetic and lethargic. First you try to go about it directly and shake them up, and when you see it’s not working, then maybe the shock caused by a TF can succeed in stirring them up”.

- Cognitive

“I’m always more concerned by the broad consequences, because although I may have gained a change in momentum, there is also significance in how I am perceived by my players. Acting legitimately is no less important. I know a TF may help change the momentum, but it may also allow my players to lose control or to talk unacceptably to the referees”.

“I find this question difficult to answer because it impacts each player differently. One might wonder, ‘what is this idiot doing’? We’ll lose momentum because of him. It depends on how well you know your team”.

“It affects each player differently, some don’t like it. They look at you and ask, ‘what the hell are you doing”.

- (2)

- Impact on Referees

“Psychologically, it may (affect) a referee, who will then whistle a little in my favor; it can’t hurt”.

“[It] depends on the skill level of the referee. If the referee’s level is high, there is not much significance. At the lower skill levels, it may have some”.

“The journalists will be excited, ‘That TF was genius,’ but you don’t know where it’s going. You make a risk assessment, and sometimes you have nothing to lose”.

“It works on the referees too. Some will say they ignore it, but I say there’ll be whistles in your favor, two-and-a-half, three minutes after the event”.

- (3)

- Impact on the Opposing Team

“First, the other team mellows; they say, ‘wait, let’s stop’. It affects them as well. The other coach suddenly becomes cautious because he says, ‘just a minute, he received a TF, they will want to get back at us’. There’s a psychological effect where he says, ‘there’s going to be payback’. So he suddenly takes a step back”.

“In general, I’d say it also gives the opponent energy”.

- (4)

- Opposing Coach’s Reaction to a TF

“My first reaction? Watch out; the referee will have his eyes on us. That’s it”.

“I respond. I can’t ignore it. First, I say to the referees, ‘Hey, listen, he committed a TF,’ and I’ll say it out loud so he can hear it too, and everyone can hear it, my players and the crowd. It’s psychology, so I do it vocally and theatrically”.

“Extinguish the situation. If the referee comes, I say, ‘What is he thinking, tell me, now you’ll start whistling against me?’ Then I say to my players, ‘Notice how the next two whistles go to the other team. Don’t get over-excited; I’m talking from experience’”.

Sam stated similarly, “I tell my guys, ‘okay, he’s trying to do something here, let’s be even stronger together’”.

3.3. Theme #3. Momentum Change

3.3.1. Tools for Reversing a Negative Momentum

“It could be a substitution of two players that suddenly stirs the team. It could be a timeout that stops the negative psychological momentum. It could be a deliberate TF, but then the team takes it hard, saying, ‘wait, something happened here’, so we sometimes even pour water on the court to stop the game for a moment. We even tell a player, ‘you’re injured, lie down’, to pause the game. It’s a bit extreme and theatrical, but you want to stop this thing for a moment”.

“Everything, from changing the defensive and offensive tactics, substituting a player, taking a timeout. A coach has ways to stop the game”.

“I’ll do anything to stop the game when needed, even extreme action. For example, for me, extreme action is to attack the referees, or, and I’ve done this more than once in my life, to grab my player and shake him until blood comes out of his ear. It’s taking my number one player and pressuring him. I mean, [doing] something unpredictable”.

“If I see a snowball effect of negative momentum, I immediately take a timeout. If I think a substitution can stop it, or a TF can stop it, if I think that a word with the referee, or something that disrupts the pace of the game will stop it, or if I can tell a player to untie his shoelaces, we do that too”.

3.3.2. TF as a Tool for Reversing Momentum

- (1)

- The Effectiveness of TFs as a Momentum-Reversing Tool

“It does make a difference. Players who care, feel connected to the team, and aren’t among the few indifferent and apathetic individuals, are affected. It does make a difference”.

“Why would you commit a TF? To change the situation, to change the momentum. You don’t do it just to gain two or three whistles in your favor. First, you stop the momentum. You want the momentum change to impact the referee, change the game, change the pace, so you do it, you initiate it. From 1 to 5? I would give it a 3.5–4 that it works”.

“Overall, I think it’s somewhere between a neutral and a small positive effect. There may only be some small effects. I’ll be surprised if you bring about a meaningful change”.

- (2)

- Professional Ethics

“As a young coach I wouldn’t use anything related to TFs as a method. I don’t think that it should be used systematically. Let the players understand that something unusual happened when you got a technical foul. But you must make them understand that you haven’t lost control”.

“No [as a recommendation to a young coach]. Start coaching, start working, and don’t start managing the game. Be strong, promote the kids, and work hard. Don’t get involved in all this nonsense; it’s not suitable for youngsters”.

“I would tell him to try to focus on the essence. Try not to use a TF, only when you feel you have no choice”.

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goffman, E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life; Penguin: Harmondsworth, UK, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Lantis, R.M.; Nesson, E.T. The Hot Hand in the NBA 3-Point Contest: The Importance of Location, Location, Location; (No. w29468); National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mews, S.; Ötting, M. Continuous-time state-space modelling of the hot hand in basketball. AStA Adv. Stat. Anal. 2023, 107, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimer, L.; Steinert-Threlkeld, Z.C.; Coltin, K. A causal approach for detecting team-level momentum in NBA games. J. Sports Anal. 2023, 9, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, E.; Chen, J.; Thomas, M. Momentum in Repeated Competition: Exploiting the Fine Line between Winning And Losing. 2019. 2019. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3391748 (accessed on 23 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Schoen, C. A qualitative study of momentum in basketball: Practical lessons, possible strategies (Case Study). J. Sport 2015, 4, 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avugos, S.; Köppen, J.; Czienskowski, U.; Raab, M.; Bar-Eli, M. The “hot hand” reconsidered: A meta-analytic approach. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 14, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, C.P.; Elmore, R.; Fosdick, B.K. The causal effect of a timeout at stopping an opposing run in the NBA. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2022, 16, 1359–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permutt, S. The Efficacy of Momentum-Stopping Timeouts on Short-Term Performance in the National Basketball Association. Thesis, Bryn Mawr College. 2011. Available online: https://scholarship.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/bitstream/handle/ 10066/6918/2011PermuttS thesis.pdf?sequence=2 (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Adler, P.; Adler, P.A. The role of momentum in sport. Urban Life 1978, 7, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iso-Ahola, S.E.; Mobily, K. “Psychological momentum”: A phenomenon and an empirical (unobtrusive) validation of its influence in a competitive sport tournament. Psych. Rep. 1980, 46, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crust, L.; Nesti, M. A review of psychological momentum in sports: Why qualitative research is needed. Athl. Insight 2006, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Vallerand, J.V.; Colavecchio, P.G.; Pelletier, L.G. Psychological momentum and performance inferences: A preliminary test of the antecedents-consequences psychological momentum model. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1985, 10, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.M.; Cornelius, A.E.; Finch, L.M. Psychological momentum and skill performance: A laboratory study. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1992, 14, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Demick, A. A multidimensional model of momentum in sports. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 1994, 6, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.I.; Harwood, C. Psychological momentum within competitive soccer: Players’ perspectives. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2008, 20, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.; Avugos, S.; Ortega, E.; Bar-Eli, M. Adverse effects of TFs in elite basketball performance. Biol. Sport 2019, 36, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zitek, E.M.; Jordan, A.H. Technical fouls predict performance outcomes in the NBA. Athl. Insight 2011, 3, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lev, A.; Galily, Y.; Eldadi, O.; Tenenbaum, G. Deconstructing celebratory acts following goal scoring among elite professional football players. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Weidenfield & Nicolson: London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes, A.C.; Smith, B. Qualitative Research Methods in Sport, Exercise and Health: From Process to Product; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K. Systematic text condensation: A strategy for qualitative analysis. Scand. J. Pub. Health 2012, 40, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgi, A.P. (Ed.) Phenomenology and Psychological Research; Duquesne University Press: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual. Inquiry 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L.; Quincy, C.; Osserman, J.; Pedersen, O.K. Coding in-depth semi-structured interviews: Problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociol. Methods Res. 2013, 42, 294–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briki, W.; den Hartigh, R.J.; Bakker, C.F.; Gernigon, C. The dynamics of psychological momentum: A quantitative study in natural sport situations. Int. J. Perf. Anal. in Sport 2012, 12, 573–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lev, A.; Weinish, S. Lost in transition: Analyzing the lifecycle of Israeli football stars in becoming coaches. Israel Affairs 2020, 26, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsade, S.G. The ripple effect: Emotional contagion and its influence on group behavior. Admin. Sci. Quar. 2002, 47, 644–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kleef, G.A.; Fischer, A.H. Emotional collectives: How groups shape emotions and emotions shape groups. Cognit. Emot. 2015, 30, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.J.; Pierce, D.A. Officiating bias: The effect of foul differential on foul calls in NCAA basketball. J. Sports Sci. 2009, 27, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tenenbaum, G.; Vigodsky, A.; Lev, A. Coaches’ Mind Games: Harnessing Technical Fouls for Psychological Momentum in Basketball. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 904. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110904

Tenenbaum G, Vigodsky A, Lev A. Coaches’ Mind Games: Harnessing Technical Fouls for Psychological Momentum in Basketball. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(11):904. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110904

Chicago/Turabian StyleTenenbaum, Gershon, Ady Vigodsky, and Assaf Lev. 2023. "Coaches’ Mind Games: Harnessing Technical Fouls for Psychological Momentum in Basketball" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 11: 904. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110904

APA StyleTenenbaum, G., Vigodsky, A., & Lev, A. (2023). Coaches’ Mind Games: Harnessing Technical Fouls for Psychological Momentum in Basketball. Behavioral Sciences, 13(11), 904. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110904