The Effects of Emotion, Spokesperson Type, and Benefit Appeals on Persuasion in Health Advertisements: Evidence from Macao

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

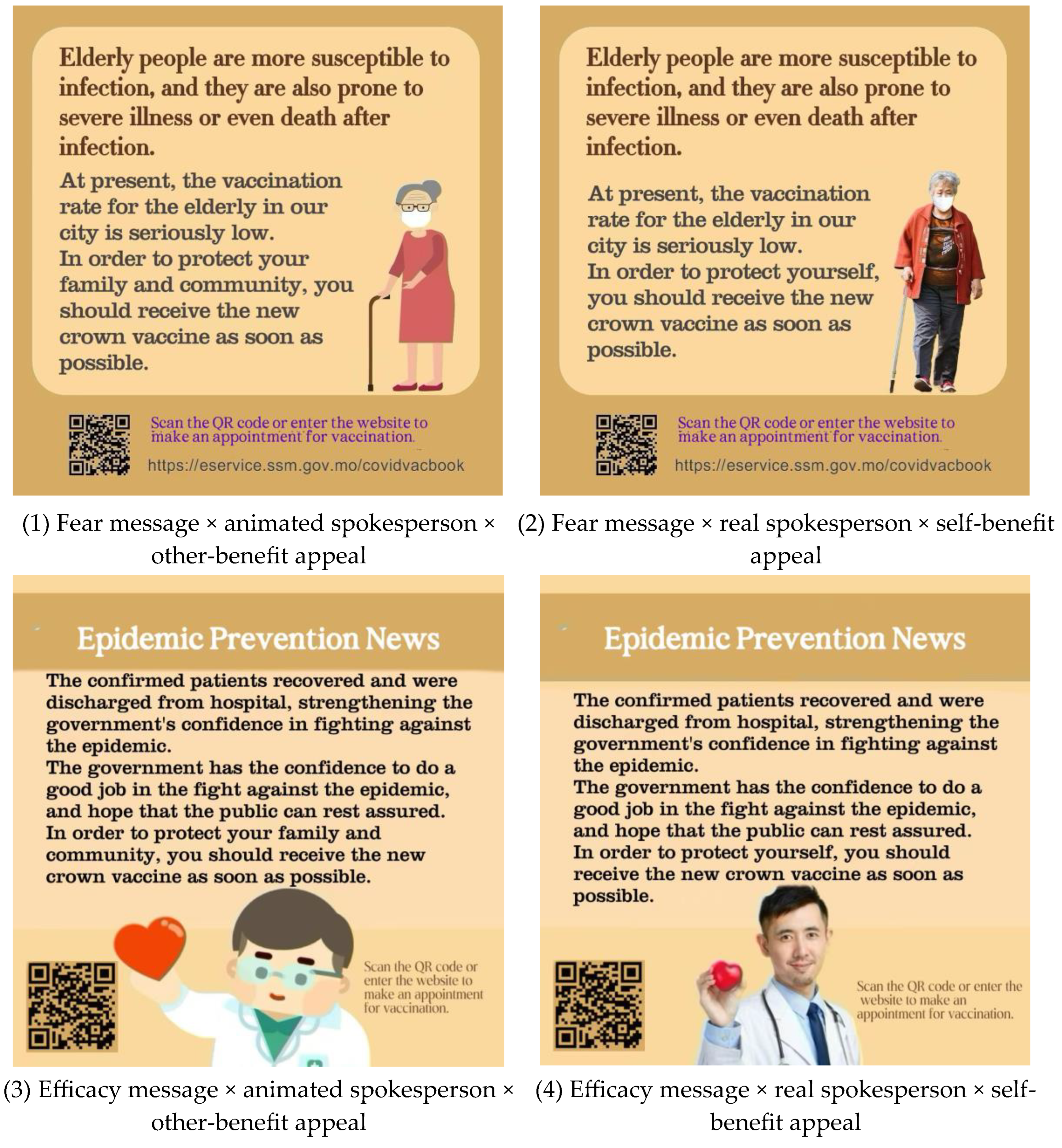

2.1. Emotion Appeals in Health Campaigns

2.2. Animated and Human Spokespersons

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Emotion Appeals and Spokespersons

3.2. Self-Benefit Appeal versus Other-Benefit Appeal

4. Methods

4.1. Experimental Procedure

4.2. Study Design

4.3. Pilot Study: Experimental Stimuli Development

4.4. Main Experiment: Hypothesis Test

4.5. Measures

4.6. Results

4.6.1. Demographic Characteristics

4.6.2. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Garretson, J.A.; Burton, S. The role of spokescharacters as advertisement and package cues in integrated marketing communications. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffner, J.; Vives, M.; FeldmanHall, O. Emotional responses to prosocial messages increase willingness to self-isolate during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 170, 110420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robberson, M.R.; Rogers, R.W. Beyond fear appeals: Negative and positive persuasive appeals to health and self-esteem. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 18, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerend, M.A.; Sias, T. Message framing and color priming: How subtle threat cues affect persuasion. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 999–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, K.; Allen, M. A Meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Educ. Behav. 2000, 27, 591–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutada, N.S.; Rollins, B.L.; Perri, M., III. Impact of animated spokes-characters in print direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising: An elaboration likelihood model approach. Health Commun. 2017, 32, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillipsa, B.J.; Sedgewickb, J.R.; Slobodziana, A.D. Spokes-characters in print advertising: An update and extension. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2019, 40, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, I.; Hosany, S.; Wu, M.S.; Chen, C.H.; Nguyen, B. Size does matter: Effects of in-game advertising stimuli on brand recall and brand recognition. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 86, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Chen, P. Anthropomorphism and object attachment. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 39, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- White, K.; Peloza, J. Self-benefit versus other-benefit marketing appeals: Their effectiveness in generating charitable support. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryoo, Y.; Sung, Y.; Chechelnytska, I. What makes materialistic consumers more ethical? Self-benefit vs. other-benefit appeals. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 110, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, M.; Hayran, C. Message framing effects on individuals’ social distancing and helping behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 579164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhart, A.M.; Marshall, H.M.; Feeley, T.H.; Frank, T. The persuasive effects of message framing in organ donation: The mediating role of psychological reactance. Commun. Monogr. 2007, 74, 229–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, A.E.; Levy, E. Helping others or oneself: How direction of comparison affects prosocial behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2016, 26, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, T.A.; Nisbet, M.C.; Maibach, E.W.; Leiserowitz, A.A. A public health frame arouses hopeful emotions about climate change. Clim. Chang. 2012, 113, 1105–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, N.; Brigaud, E. Humor in print health advertisements: Enhanced attention, privileged recognition, and persuasiveness of preventive messages. Health Commun. 2014, 29, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pounders, K.R.; Lee, S.; Mackert, M. Matching temporal frame, self-view, and message frame valence: Improving persuasiveness in health communications. J. Advert. 2015, 44, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; Mazzoni, D.; Cicognani, E.; Albanesi, C.; Zani, B. Evaluating the persuasiveness of an HIV mass communication campaign using gain framed messages and aimed at creating a superordinate identity. Health Commun. 2016, 31, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.S.; Feldman, L. Threat without efficacy? Climate change on US network news. Sci. Commun. 2014, 36, 325–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Hope and climate change: The importance of hope for environmental engagement among young people. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 625–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, R.L. Emotional flow in persuasive health messages. Health Commun. 2015, 30, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabi, R.L.; Gustafson, A.; Jensen, R. Framing climate change: Exploring the role of emotion in generating advocacy behavior. Sci. Commun. 2018, 40, 442–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, J.P.; Shen, L. On the nature of reactance and its role in persuasive health communication. Commun. Monogr. 2005, 72, 144–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, A.S.; Banas, J.A. Inoculating against reactance to persuasive health messages. Health Commun. 2015, 30, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rains, S.A.; Turner, M.M. Psychological reactance and persuasive health communication: A test and extension of the intertwined model. Hum. Commun. Res. 2007, 33, 241–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; Pietrantoni, L.; Zani, B. Influenza vaccination: The persuasiveness of messages among people aged 65 years and older. Health Commun. 2012, 27, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touré-Tillery, M.; McGill, A.L. Who or what to believe: Trust and the differential persuasiveness of human and anthropomorphized messengers. J. Mark. 2015, 79, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiser, R.S.; Sierra, J.J.; Torres, I.M. Creativity via cartoon spokespeople in print ads: Capitalizing on the distinctiveness effect. J. Advert. 2008, 37, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, F.J.; Newton, J.D.; Wong, J. This is your stomach speaking: Anthropomorphized health messages reduce portion size preferences among the powerless. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 75, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; McGill, A.L. Gaming with Mr. slot or gaming the slot machine? Power, anthropomorphism, and risk perception. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 38, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letheren, K.; Martin, B.A.S.; Jin, H.S. Effects of personification and anthropomorphic tendency on destination attitude and travel intentions. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labroo, A.A.; Dhar, R.; Schwarz, N. Of frog wines and frowning watches: Semantic priming, perceptual fluency, and brand evaluation. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 34, 819–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.Y.; Labroo, A.A. The effect of conceptual and perceptual fluency on brand evaluation. J. Mark. Res. 2004, 41, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.; Schwarz, N. Use does not wear ragged the fabric of friendship: Thinking of objects as alive makes people less willing to replace them. J. Consum. Psychol. 2010, 20, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.J.; Hornik, R.C. Effects of framing health messages in terms of benefits to loved ones or others: An experimental study. Health Commun. 2016, 31, 1284–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.J.; Yoeli, E.; Rand, D.G. Don’t get it or don’t spread it: Comparing self-interested versus prosocial motivations for COVID-19 prevention behaviors. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vietri, J.T.; Li, M.; Galvani, A.P.; Chapman, G.B. Vaccinating to help ourselves and others. Med. Decis. Mak. 2012, 32, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J.G.; Miller, D.T.; Lerner, M.J. Committing altruism under the cloak of self-interest: The exchange fiction. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 38, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, D.J.; Ellsworth, P.C.; Gonzalez, R. Are manipulation checks necessary? Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Sui, M. The moderating effects of perceived severity on the generational gap in preventive behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilakkuvan, V.; Turner, M.M.; Cantrell, J.; Hair, E.; Vallone, D. The relationship between advertising-induced anger and self-efficacy on persuasive outcomes a test of the anger activism model using the truth campaign. Fam. Community Health 2017, 40, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Tracking and Tracing COVID: Protecting Privacy and Data While Using Apps and Biometrics. Available online: www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/tracking-and-tracing-covid-protecting-privacy-and-data-while-using-apps-and-biometrics-8f394636/ (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Wang, J.P.; Sundar, S.S. Are we more reactive to persuasive health messages when they appear in our customized interfaces? The role of sense of identity and sense of control. Health Commun. 2022, 37, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanyaolu, A.; Okorie, C.; Hosein, Z.; Patidar, R.; Desai, P.; Prakash, S.; Jaferi, U.; Mangat, J.; Marinkovic, A. Global Pandemicity of COVID-19: Situation Report as of June 9, 2020. Infect. Dis. Res. Treat. 2021, 14, 1178633721991260. [Google Scholar]

- Christner, N.; Sticker, R.M.; Söldner, L.; Mammen, M.; Paulus, M. Prevention for oneself or others? Psychological and social factors that explain social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 27, 1342–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumer, A.; Schweizer, T.; Bogdanić, V.; Boecker, L.; Loschelder, D.D. How health message framing and targets affect distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Psychol. 2022, 41, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, E.; Reeve, K.S.; Niedzwiedz, C.L.; Moore, J.; Blake, M.; Green, M.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Benzeval, M.J. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK household longitudinal study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 94, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitake, N.; Omori, M.; Sugawara, M.; Akishinonomiya, K.; Shimada, S. Do health beliefs, personality traits, and interpersonal concerns predict TB prevention behavior among Japanese adults? PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.Y.; Han, K. Social Motivation to Comply with COVID-19 Guidelines in Daily Life in South Korea and the United States. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzuca, D.; Della Corte, M.; Guarna, F.; Pallocci, M.; Passalacqua, P.; Gratteri, S. COVID-19 as a health education challenge: A perspective cross-sectional study. Acta Med. Mediterr. 2022, 38, 1725–1731. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Categories | N | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 516 | 47.1% |

| Female | 579 | 52.9% | |

| Age | 18–24 | 172 | 15.7% |

| 25–39 | 429 | 39.2% | |

| 40–54 | 268 | 24.5% | |

| 55 and above | 226 | 20.6% | |

| Education | High school diploma or less | 262 | 23.9% |

| Associate’s degree | 295 | 26.9% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 334 | 30.5% | |

| Above Bachelor | 204 | 18.6% |

| Source | Dependent Variable | Mean Square | F | p Value | Partial η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Appeal (EA) | Perceived Severity | 1521.401 | 1481.627 | <0.001 | 0.576 |

| Spokesperson Type (ST) | 198.300 | 193.116 | <0.001 | 0.150 | |

| EA × ST | 11.063 | 10.774 | 0.001 | 0.010 | |

| R2 = 0.607 (Adjusted R2 = 0.606) | |||||

| Emotional Appeal (EA) | Message Receptivity | 213.649 | 149.721 | <0.001 | 0.121 |

| Spokesperson Type (EA) | 188.655 | 132.206 | <0.001 | 0.108 | |

| EA × ST | 11.508 | 8.065 | 0.005 | 0.007 | |

| R2 = 0.210 (Adjusted R2 = 0.208) | |||||

| Source | Mean Square | F | p Value | Partial η2 | Observed Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Appeal (EA) | 6.342 | 4.416 | 0.036 * | 0.004 | 0.556 |

| Spokesperson Type (ST) | 0.518 | 0.361 | 0.548 | 0.000 | 0.092 |

| Benefit Appeal (BA) | 2.116 | 1.473 | 0.225 | 0.001 | 0.228 |

| EA × ST | 2.992 | 2.084 | 0.149 | 0.002 | 0.303 |

| EA × BA | 1414.052 | 984.706 | <0.001 *** | 0.475 | 1.000 |

| ST × BA | 8.979 | 6.253 | 0.013 * | 0.006 | 0.705 |

| EA × ST × BA | 6.977 | 4.858 | 0.028 * | 0.004 | 0.596 |

| Self-Benefit | Other-Benefit | Mean Square | F | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fear | Real | Mean = 5.583 | Mean = 2.882 | 503.462 | 350.597 | <0.001 |

| SD = 1.259 | SD = 1.414 | |||||

| (n = 141) | (n = 135) | |||||

| Animated | Mean = 5.182 | Mean = 3.161 | 278.522 | 193.955 | <0.001 | |

| SD = 1.228 | SD = 1.022 | |||||

| (n = 135) | (n = 138) | |||||

| Efficacy | Real | Mean = 3.198 | Mean = 5.362 | 320.543 | 223.217 | <0.001 |

| SD = 1.147 | SD = 1.166 | |||||

| (n = 140) | (n = 134) | |||||

| Animated | Mean = 3.325 | Mean = 5.532 | 331.099 | 230.568 | <0.001 | |

| SD = 1.310 | SD = 0.980 | |||||

| (n = 137) | (n = 135) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, L.; Liu, H.; Jiang, N. The Effects of Emotion, Spokesperson Type, and Benefit Appeals on Persuasion in Health Advertisements: Evidence from Macao. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 917. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110917

Jiang L, Liu H, Jiang N. The Effects of Emotion, Spokesperson Type, and Benefit Appeals on Persuasion in Health Advertisements: Evidence from Macao. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(11):917. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110917

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Ling, Huihui Liu, and Nan Jiang. 2023. "The Effects of Emotion, Spokesperson Type, and Benefit Appeals on Persuasion in Health Advertisements: Evidence from Macao" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 11: 917. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110917

APA StyleJiang, L., Liu, H., & Jiang, N. (2023). The Effects of Emotion, Spokesperson Type, and Benefit Appeals on Persuasion in Health Advertisements: Evidence from Macao. Behavioral Sciences, 13(11), 917. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110917