Romantic Love and Behavioral Activation System Sensitivity to a Loved One

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Romantic Love

1.2. The Behavioral Activation System (BAS)

1.3. The BAS and Romantic Love

1.4. Salience of Loved One-Related Stimuli and the BAS

1.5. The BAS Scale

1.6. The Current Studies

2. Study 1: Validating the BAS-SLO Scale

2.1. Materials and Methods

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Measures

2.1.3. Procedure

2.2. Results

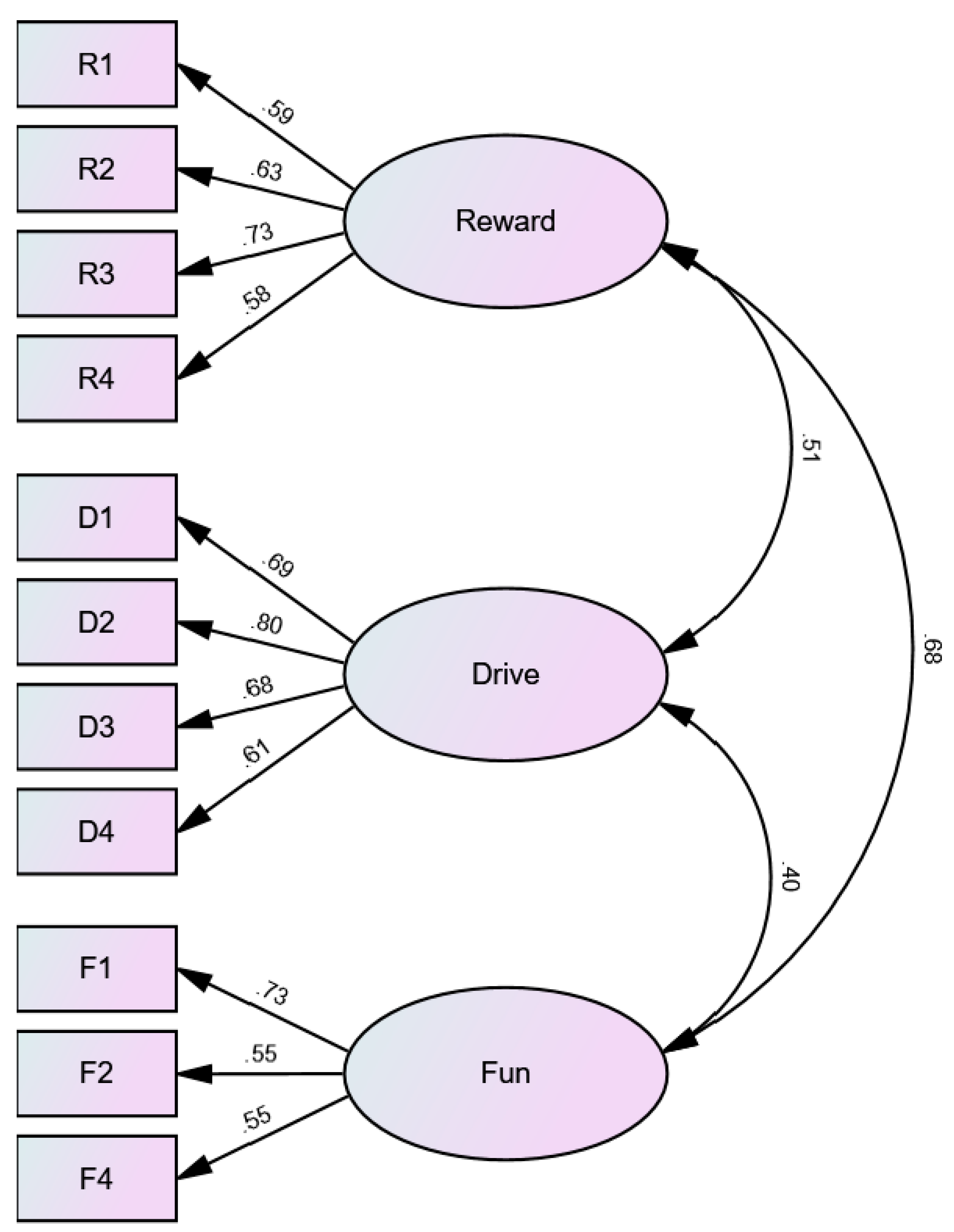

2.2.1. Three-Factor, 13-Item Model

2.2.2. One-Factor, 13-Item Model

2.2.3. Three-Factor, 11-Item Model

2.3. Discussion

3. Study 2: The BAS and Romantic Love

3.1. Materials and Methods

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Measures

3.1.3. Procedure

3.2. Results

3.3. Discussion

4. General Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Range | Mean | SD | Median | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | 1556 | 100.00 | ||||

| Female | 814 | 52.31 | ||||

| Heterosexual | 1142 | 73.39 | ||||

| Age | 18.00, 25.00 | 22.44 | 1.83 | 23.00 | ||

| PLS-30 (mean item; 1–9) | 1.93, 9.00 | 7.02 | 1.13 | 7.17 | ||

| TLS-Commitment (mean item; 1–9) | 1.80, 9.00 | 7.57 | 1.34 | 7.80 | ||

| Time thinking (%) | 1.00, 100.00 | 49.68 | 23.45 | 50.00 | ||

| Dating, not co-habiting | 479 | 30.78 | ||||

| Committed, not co-habiting | 715 | 45.95 | ||||

| Committed, co-habiting | 314 | 20.18 | ||||

| Married or de facto | 48 | 3.08 | ||||

| Years in love (0–10 or more) | 0.00, 10.00 | 1.90 | 2.15 | 1.00 | ||

| Relationship duration (years) | 0.00, 10.00 | 1.82 | 2.05 | 1.00 | ||

| Relationship satisfaction (1–5) | 1.00, 5.00 | 4.25 | 0.78 | 4.00 | ||

| HCL-32 (0–32) | 0.00, 28.00 | 16.38 | 4.91 | 17.00 | ||

| Having sex (no/yes) | 1377 | 88.62 | ||||

| Sex times per week | 0.00, 30.00 | 3.03 | 2.79 | 2.00 | ||

| >13 years of education | 1352 | 86.89 | ||||

| Current student (no/yes) | 1046 | 67.22 | ||||

| Not working | 629 | 40.42 | ||||

| Less than full-time work | 491 | 31.56 | ||||

| Full-time work | 436 | 28.02 | ||||

| AQOL-4D (12–48) | 12.00, 35.00 | 17.59 | 3.48 | 17.00 |

| Country | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| South Africa | 182 | 11.70 |

| Poland | 136 | 8.74 |

| Mexico | 115 | 7.39 |

| Portugal | 111 | 7.13 |

| Italy | 110 | 7.07 |

| UK and NI | 109 | 7.01 |

| Greece | 93 | 5.98 |

| USA | 91 | 5.85 |

| Spain | 90 | 5.78 |

| Germany | 76 | 4.88 |

| Hungary | 67 | 4.31 |

| Netherlands | 67 | 4.31 |

| Canada | 43 | 2.76 |

| Chile | 36 | 2.31 |

| France | 31 | 1.99 |

| Czech Republic | 23 | 1.48 |

| Slovenia | 23 | 1.48 |

| Australia | 20 | 1.29 |

| Belgium | 20 | 1.29 |

| Estonia | 18 | 1.16 |

| Latvia | 18 | 1.16 |

| Rest of sample | 77 | 4.95 |

Appendix B

| CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | >0.950 (0.900) | <0.060 | <0.080 |

| One-factor model | 0.709 | 0.121 | 0.086 |

| Three-factor model (13 items) | 0.944 | 0.055 | 0.041 |

| Three-factor model (11 items) | 0.966 | 0.048 | 0.037 |

Appendix C

Appendix D

| Item | BAS Scale Items | BAS-SLO Scale Items |

|---|---|---|

| Reward responsiveness subscale | ||

| 1 | When I’m doing well at something, I love to keep at it. | When I’m doing well at something my partner values, I love to keep at it |

| 2 | When I get something I want, I feel excited and energized | When my partner tells me they love me, I feel excited and energized |

| 3 | When I see an opportunity for something I like, I get excited right away | When I see an opportunity to spend time with my partner, I get excited right away |

| 4 | When good things happen to me, it affects me strongly | When good things happen to my partner, it affects me strongly |

| Drive subscale | ||

| 1 | I go out of my way to get things I want | I go out of my way to maintain my relationship with my partner |

| 2 | When I want something, I usually go all-out to get it | When it comes to maintaining my relationship with my partner, I usually go all-out |

| 3 | If I see a chance to get something I want, I move on it right away | If I see a chance to strengthen my relationship with my partner, I move on it straight away |

| 4 | When I go after something, I use a “no holds barred” approach | When it comes to maintaining my relationship with my partner, I use a “no holds barred” approach |

| Fun-seeking subscale | ||

| 1 | I’m always willing to try something new if I think it will be fun | I’m always willing to try new things with my partner if I think it will be fun |

| 2 | I will often do things for no other reason than that they might be fun | I will often do things with my partner for no other reason than they are fun |

| 3 | I crave excitement and new sensations | I crave excitement and new sensations with my partner |

Appendix E

| Range | Mean | SD | Median | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | 812 | 100.00 | ||||

| Female | 389 | 47.91 | ||||

| Heterosexual | 592 | 72.91 | ||||

| Age | 18.00, 25.00 | 22.16 | 1.86 | 22.00 | ||

| PLS-30 (mean item; 1–9) | 4.37, 9.00 | 6.99 | 1.04 | 7.10 | ||

| TLS-Commitment (mean item; 1–9) | 2.00, 9.00 | 1.22 | 1.37 | 7.60 | ||

| Time thinking (%) | 2.00, 100.00 | 49.10 | 22.58 | 49.00 | ||

| Dating, not co-habiting | 358 | 44.09 | ||||

| Committed, not co-habiting | 373 | 45.94 | ||||

| Committed, co-habiting | 75 | 9.24 | ||||

| Married or de facto | 6 | 0.74 | ||||

| Months in love (0–23) | ||||||

| Relationship satisfaction (1–5) | 1.00, 5.00 | 4.18 | 0.78 | 4.00 | ||

| HCL-32 (0–32) | 0.00, 28.00 | 16.35 | 4.79 | 17.00 | ||

| Having sex (no/yes) | 722 | 89.04 | ||||

| Sex times per week | 0.00, 20.00 | 3.21 | 2.87 | 3.00 | ||

| >13 years of education | 693 | 85.34 | ||||

| Current student (no/yes) | 569 | 70.07 | ||||

| Not working | 355 | 43.72 | ||||

| Less than full-time work | 275 | 33.87 | ||||

| Full-time work | 182 | 22.41 | ||||

| AQOL-4D (12–48) | 12.00, 35.00 | 17.55 | 3.47 | 17.00 |

| Country | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| South Africa | 101 | 12.44 |

| Poland | 73 | 8.99 |

| UK and NI | 59 | 7.27 |

| Portugal | 57 | 7.02 |

| Mexico | 56 | 6.90 |

| Greece | 51 | 6.28 |

| Germany | 50 | 6.16 |

| Spain | 49 | 6.03 |

| Italy | 47 | 5.79 |

| USA | 39 | 4.80 |

| Hungary | 38 | 4.68 |

| The Netherlands | 31 | 3.82 |

| Canada | 22 | 2.71 |

| Chile | 22 | 2.71 |

| France | 16 | 1.97 |

| Slovenia | 14 | 1.72 |

| Estonia | 11 | 1.35 |

| Australia | 10 | 1.23 |

| Czech Republic | 10 | 1.23 |

| Latvia | 9 | 1.11 |

| Austria | 8 | 0.99 |

| Rest of sample | 39 | 4.80 |

References

- Rusu, M.S. Theorising love in sociological thought: Classical contributions to a sociology of love. J. Class. Sociol. 2017, 18, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rougemont, D. Love in the Western World; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowiak, W.R. (Ed.) Romantic Passion: A Universal Experience? Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield, E.; Walster, G.W. A New Look at Love, 1985 ed.; University Press of America: Lanham, MD, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Karandashev, V. Cultural Typologies of Love; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, A.; Kushnick, G. Proximate and Ultimate Perspectives on Romantic Love. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, A.; Kowal, M. Toward consistent reporting of sample characteristics in studies investigating the biological mechanisms of romantic love. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 983419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feybesse, C.; Hatfield, E. Passionate Love. In The New Psychology of Love, 2nd ed.; Sternberg, R.J., Sternberg, K., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowiak, W.R. (Ed.) Intimacies: Love and Sex Across Cultures; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield, E.; Sprecher, S. Measuring passionate love in intimate relationships. J. Adolesc. 1986, 9, 383–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karandashev, V. Romantic Love in Cultural Contexts; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Karandashev, V. Cross-Cultural Perspectives on the Experience and Expression of Love; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tennov, D. Love and Limerence: The Experience of Being in Love; Stein & Day: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bringle, R.G.; Winnick, T.; Rydell, R.J. The Prevalence and Nature of Unrequited Love. SAGE Open 2013, 3, 2158244013492160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, K.D.; Acevedo, B.P.; Aron, A.; Huddy, L.; Mashek, D. Is Long-Term Love More Than A Rare Phenomenon? If So, What Are Its Correlates? Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2011, 3, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, B.P.; Aron, A. Does a Long-Term Relationship Kill Romantic Love? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2009, 13, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheets, V.L. Passion for life: Self-expansion and passionate love across the life span. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2013, 31, 958–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, S.; Bianchi-Demicheli, F.; Hatfield, E.; Rapson, R.L. Social Neuroscience of Love. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2012, 9, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.W.; Zou, Z.L.; Kou, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.Z.; Zilverstand, A.; Uquillas, F.D.; Zhang, X.C. Love-related changes in the brain: A resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Song, S.S.; Uquillas, F.D.; Zilverstand, A.; Song, H.W.; Chen, H.; Zou, Z.L. Altered brain network organization in romantic love as measured with resting-state fMRI and graph theory. Brain Imaging Behav. 2020, 14, 2771–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.X.; Zhuang, J.Y.; Fu, L.; Lei, Q.; Fan, M.; Zhang, W. How ovarian hormones influence the behavioral activation and inhibition system through the dopamine pathway. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes-Claramonte, P.; Ávila, C.; Rodríguez-Pujadas, A.; Ventura-Campos, N.; Bustamante, J.C.; Costumero, V.; Rosell-Negre, P.; Barrós-Loscertales, A. Reward sensitivity modulates brain activity in the prefrontal cortex, ACC and striatum during task switching. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoya, J.L.; Landi, N.; Kober, H.; Worhunsky, P.D.; Rutherford, H.J.; Mencl, W.E.; Mayes, L.C.; Potenza, M.N. Regional brain responses in nulliparous women to emotional infant stimuli. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qiao, L.; Sun, J.; Wei, D.; Li, W.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, H. Gender-specific neuroanatomical basis of behavioral inhibition/approach systems (BIS/BAS) in a large sample of young adults: A voxel-based morphometric investigation. Behav. Brain Res. 2014, 274, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.L.; Edge, M.D.; Holmes, M.K.; Carver, C.S. The behavioral activation system and mania. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 8, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, H.E. Lust, attraction, and attachment in mammalian reproduction. Hum. Nat. -Interdiscip. Biosoc. Perspect. 1998, 9, 23–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrick, C.; Hendrick, S. A theory and method of love. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 50, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivers, R.L. Parental investment and sexual selection. In Sexual Selection and the Descent of Man; Campbell, B., Ed.; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1972; pp. 136–179. [Google Scholar]

- Wachtmeister, C.-A.; Enquist, M. The evolution of courtship rituals in monogamous species. Behav. Ecol. 2000, 11, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farris, C.; Treat, T.A.; Viken, R.J.; McFall, R.M. Sexual coercion and the misperception of sexual intent. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 28, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.; Luethi, M.; von Planta, A.; Hatzinger, M.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E. Romantic love, hypomania, and sleep pattern in adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 41, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froemke, R.; Young, L. Oxytocin, Neural Plasticity, and Social Behavior. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2021, 44, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bode, A. Romantic love evolved by co-opting mother-infant bonding. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1176067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langeslag, S.; Olivier, J.; Köhlen, M.; Nijs, I.; Van Strien, J. Increased attention and memory for beloved-related information during infatuation: Behavioral and electrophysiological data. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2015, 10, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.E. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Self-Evaluation Questionanire); COnsulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C.S.; White, T.L. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS Scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, D.; Almeida, F.; Pinto, M.; Segarra, P.; Barbosa, F. Data concerning the psychometric properties of the Behavioral Inhibition/Behavioral Activation Scales for the Portuguese population. Psychol. Assess. 2015, 27, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maack, D.J.; Ebesutani, C. A re-examination of the BIS/BAS scales: Evidence for BIS and BAS as unidimensional scales. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 27, e1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogswell, A.; Alloy, L.B.; van Dulmen, M.H.M.; Fresco, D.M. A psychometric evaluation of behavioral inhibition and approach self-report measures. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 40, 1649–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wang, J.; Jin, Z.; Xia, L.; Lian, Q.; Huyang, S.; Wu, D. The Behavioral Inhibition System/Behavioral Activation System Scales: Measurement Invariance Across Gender in Chinese University Students. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 681753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Q.; Yang, P.; Gao, H.; Liu, M.; Zhang, J.; Cai, T. Application of the Chinese Version of the BIS/BAS Scales in Participants With a Substance Use Disorder: An Analysis of Psychometric Properties and Comparison With Community Residents. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Sills, L.; Liverant, G.I.; Brown, T.A. Psychometric evaluation of the behavioral inhibition/behavioral activation scales in a large sample of outpatients with anxiety and mood disorders. Psychol. Assess. 2004, 16, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F.; Christensen, H.; Henderson, A.S.; Jacomb, P.A.; Korten, A.E.; Rodgers, B. Using the BIS/BAS scales to measure behavioural inhibition and behavioural activation: Factor structure, validity and norms in a large community sample. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1999, 26, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heubeck, B.G.; Wilkinson, R.B.; Cologon, J. A second look at Carver and White’s (1994) BIS/BAS scales. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1998, 25, 785–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, A.; Kavanagh, P.S. Romantic Love Survey 2022, 3rd ed.; UNC Dataverse: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knekta, E.; Runyon, C.; Eddy, S. One Size Doesn’t Fit All: Using Factor Analysis to Gather Validity Evidence When Using Surveys in Your Research. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2019, 18, rm1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-H. Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav. Res. Methods 2016, 48, 936–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannas Aghedu, F.; Veneziani, C.A.; Manari, T.; Feybesse, C.; Bisiacchi, P.S. Assessing passionate love: Italian validation of the PLS (reduced version). Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2018, 35, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrick, S.S.; Hendrick, C. Gender differences and similarities in sex and love. Pers. Relat. 1995, 2, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R.J. A triangular theory of love. Psychol. Rev. 1986, 93, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.; Foell, S.; Bajoghli, H.; Keshavarzi, Z.; Kalak, N.; Gerber, M.; Schmidt, N.B.; Norton, P.J.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E. “Tell me, how bright your hypomania is, and I tell you, if you are happily in love!”-Among young adults in love, bright side hypomania is related to reduced depression and anxiety, and better sleep quality. Int. J. Psychiat. Clin. 2015, 19, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langeslag, S.J.E.; van der Veen, F.M.; Fekkes, D. Blood Levels of Serotonin Are Differentially Affected by Romantic Love in Men and Women. J. Psychophysiol. 2012, 26, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowal, M.; Sorokowski, P.; Dinić, B.M.; Pisanski, K.; Gjoneska, B.; Frederick, D.A.; Pfuhl, G.; Milfont, T.L.; Bode, A.; Aguilar, L.; et al. Validation of the Short Version (TLS-15) of the Triangular Love Scale (TLS-45) across 37 Languages. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2023, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, R.H. Passion within Reason: The Strategic Role of the Emotions; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Buss, D.M. The evolution of love in humans. In The New Psychology of Love, 2nd ed.; Sternberg, R.J., Sternberg, K., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zietsch, B.P.; Sidari, M.J.; Murphy, S.C.; Sherlock, J.M.; Lee, A.J. For the good of evolutionary psychology, let’s reunite proximate and ultimate explanations. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2020, 42, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.M.; Weng, X.C.; Aron, A. The mesolimbic dopamine pathway and romantic love. In Brain Mapping: An Encyclopedic Reference; Toga, A.W., Mesulam, M.M., Kastner, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, H.-C.; Kuo, M.-E.; Wu, C.W.; Chao, Y.-P.; Huang, H.-W.; Huang, C.-M. The Neurobiological Basis of Love: A Meta-Analysis of Human Functional Neuroimaging Studies of Maternal and Passionate Love. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groppe, S.E.; Gossen, A.; Rademacher, L.; Hahn, A.; Westphal, L.; Gründer, G.; Spreckelmeyer, K.N. Oxytocin influences processing of socially relevant cues in the ventral tegmental area of the human brain. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 74, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydnor, V.J.; Larsen, B.; Kohler, C.; Crow, A.J.D.; Rush, S.L.; Calkins, M.E.; Gur, R.C.; Gur, R.E.; Ruparel, K.; Kable, J.W.; et al. Diminished reward responsiveness is associated with lower reward network GluCEST: An ultra-high field glutamate imaging study. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 2137–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, H.E. Anatomy of Love: A Natural History of Mating, Marriage, and Why We Stray, 2nd ed.; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Item | BAS Scale Items | BAS-SLO Scale Items |

|---|---|---|

| Reward responsiveness subscale | ||

| 1 | When I’m doing well at something, I love to keep at it. | When I’m doing well at something my partner values, I love to keep at it |

| 2 | When I get something I want, I feel excited and energized | When my partner tells me they love me, I feel excited and energized |

| 3 | When I see an opportunity for something I like, I get excited right away | When I see an opportunity to spend time with my partner, I get excited right away |

| 4 | When good things happen to me, it affects me strongly | When good things happen to my partner, it affects me strongly |

| 5 | It would excite me to win a contest | It would excite me for my partner and me to win a contest |

| Drive subscale | ||

| 1 | I go out of my way to get things I want | I go out of my way to maintain my relationship with my partner |

| 2 | When I want something, I usually go all-out to get it | When it comes to maintaining my relationship with my partner, I usually go all-out |

| 3 | If I see a chance to get something I want, I move on it right away | If I see a chance to strengthen my relationship with my partner, I move on it straight away |

| 4 | When I go after something, I use a “no holds barred” approach | When it comes to maintaining my relationship with my partner, I use a “no holds barred” approach |

| Fun-seeking subscale | ||

| 1 | I’m always willing to try something new if I think it will be fun | I’m always willing to try new things with my partner if I think it will be fun |

| 2 | I will often do things for no other reason than that they might be fun | I will often do things with my partner for no other reason than they are fun |

| 3 | I often act on the spur of the moment | I often act on the spur of the moment with my partner |

| 4 | I crave excitement and new sensations | I crave excitement and new sensations with my partner |

| M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | 3.58 | 0.56 | −0.92 | 0.08 |

| R2 | 3.67 | 0.55 | −1.59 | 2.21 |

| R3 | 3.56 | 0.62 | −1.23 | 0.94 |

| R4 | 3.57 | 0.64 | −1.42 | 1.86 |

| R5 | 3.56 | 0.66 | −1.37 | 1.29 |

| D1 | 3.21 | 0.77 | −0.80 | 0.30 |

| D2 | 3.12 | 0.76 | −0.65 | 0.24 |

| D3 | 3.37 | 0.71 | −0.98 | 0.74 |

| D4 | 2.84 | 0.78 | −0.23 | −0.039 |

| F1 | 3.62 | 0.57 | −1.33 | 1.55 |

| F2 | 3.42 | 0.70 | −1.00 | 0.44 |

| F3 | 3.06 | 0.73 | −0.36 | −0.34 |

| F4 | 3.34 | 0.69 | −0.67 | −0.22 |

| BAS-SLO Scale Subscales | PLS-30 |

|---|---|

| Reward | 0.560 *** |

| Drive | 0.418 *** |

| Fun-seeking | 0.358 *** |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reward responsiveness | 1 | 0.413 *** | 0.465 *** | 0.520 *** | −0.106 ** | 0.071 * | 0.207 *** | 0.450 *** |

| 2 | Drive | 1 | 0.327 *** | 0.468 *** | −0.048 | 0.099 ** | 0.308 *** | 0.344 *** | |

| 3 | Fun-seeking | 1 | 0.340 *** | −0.087 * | 0.035 | 0.121 *** | 0.262 *** | ||

| 4 | PLS-30 | 1 | −0.112 ** | 0.137 *** | 0.465 *** | 0.612 *** | |||

| 5 | Sex (male) | 1 | −0.064 | −0.209 *** | −0.074 * | ||||

| 6 | Months in love | 1 | 0.063 | 0.232 *** | |||||

| 7 | Obsessive thinking | 1 | 0.330 *** | ||||||

| 8 | Commitment | 1 | |||||||

| n | 423 | ||||||||

| % | 52.09 | ||||||||

| M | 14.33 | 12.49 | 10.43 | 209.64 | 8.13 | 49.15 | 36.55 | ||

| SD | 1.67 | 2.34 | 1.42 | 31.27 | 5.97 | 22.58 | 6.85 | ||

| 95% CI | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | Adjusted R2 | Adjusted R2 Change | b | SE | β | t | p | Lower | Upper | |

| Step 1 | 0.453 *** | 0.450 *** | ||||||||

| Sex | −0.772 | 1.668 | −0.012 | −0.463 | 0.644 | −4.046 | 2.502 | |||

| Months in love | −0.013 | 0.140 | −0.002 | −0.090 | 0.928 | −0.288 | 0.263 | |||

| Obsessive thinking | 0.405 | 0.039 | 0.292 | 10.392 | <0.001 | 0.328 | 0.481 | |||

| Commitment | 2.353 | 0.129 | 0.516 | 18.212 | <0.001 | 2.099 | 2.607 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.543 *** | 0.539 *** | 0.089 *** | |||||||

| Sex | 0.152 | 1.534 | 0.002 | 0.099 | 0.921 | −2.860 | 3.164 | |||

| Months in love | 0.019 | 0.129 | 0.004 | 0.147 | 0.883 | −0.234 | 0.272 | |||

| Obsessive thinking | 0.339 | 0.037 | 0.245 | 9.252 | <0.001 | 0.267 | 0.410 | |||

| Commitment | 1.667 | 0.131 | 0.365 | 12.733 | <0.001 | 1.410 | 1.924 | |||

| Reward responsiveness | 3.898 | 0.561 | 0.209 | 6.951 | <0.001 | 2.797 | 4.999 | |||

| Drive | 2.131 | 0.370 | 0.159 | 5.753 | <0.001 | 1.404 | 2.858 | |||

| Fun-seeking | 1.438 | 0.601 | 0.065 | 2.391 | 0.017 | 0.257 | 2.618 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bode, A.; Kavanagh, P.S. Romantic Love and Behavioral Activation System Sensitivity to a Loved One. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 921. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110921

Bode A, Kavanagh PS. Romantic Love and Behavioral Activation System Sensitivity to a Loved One. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(11):921. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110921

Chicago/Turabian StyleBode, Adam, and Phillip S. Kavanagh. 2023. "Romantic Love and Behavioral Activation System Sensitivity to a Loved One" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 11: 921. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110921

APA StyleBode, A., & Kavanagh, P. S. (2023). Romantic Love and Behavioral Activation System Sensitivity to a Loved One. Behavioral Sciences, 13(11), 921. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110921