The Association between Perceived Family Financial Stress and Adolescent Suicide Ideation: A Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Mediating Role of Depression

1.2. The Moderating Role of Parent–Child Attachment

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Family Financial Stress

2.2.2. Parent–Child Attachment Relationship

2.2.3. Depression

2.2.4. Suicidal Ideation

2.3. Common Method Bias Test

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results and Correlational Analysis

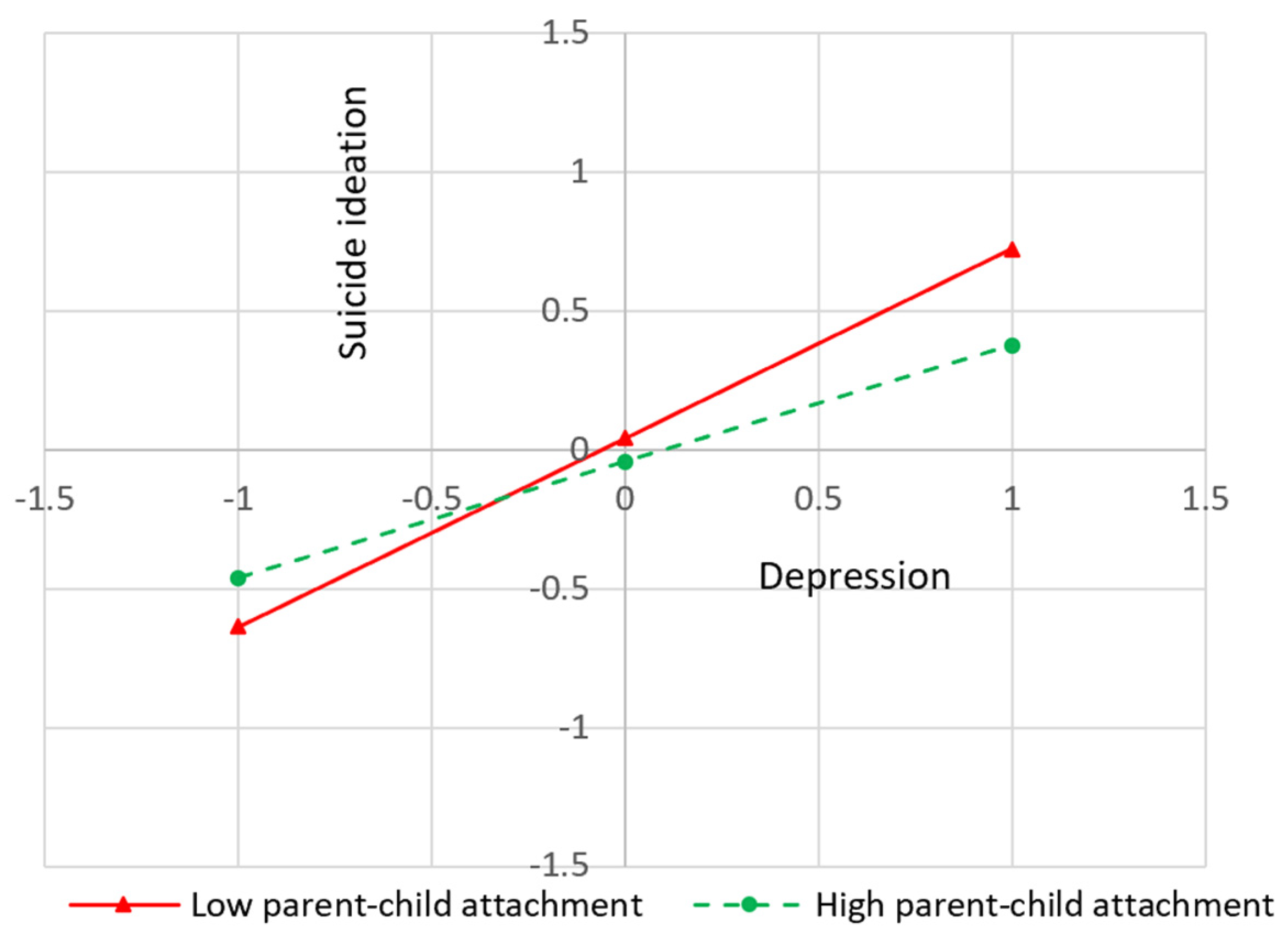

3.2. Tests of Moderated Mediation

4. Discussion

4.1. The Mediating Role of Depression

4.2. The Moderating Role of Parent–Child Attachment Relationship

4.3. Implications and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Curtin, S.C.; Heron, M.P. Death rates due to suicide and homicide among persons aged 10–24: United States, 2000–2017. NCHS Data Brief 2019, 352, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Breslin, K.; Balaban, J.; Shubkin, C.D. Adolescent suicide: What can pediatricians do? Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2020, 32, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glenn, C.R.; Kleiman, E.M.; Kellerman, J.; Pollak, O.; Cha, C.B.; Esposito, E.C.; Boatman, A.E. Annual Research Review: A meta-analytic review of worldwide suicide rates in adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard, D.S.; Gurewich, D.; Lwin, A.K.; Reed, G.A., Jr.; Silverman, M.M. Suicide and suicidal attempts in the United States: Costs and policy implications. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2016, 46, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchin, I.; Doran, C.M. The Cost of Youth Suicide in Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creuze, C.; Lestienne, L.; Vieux, M.; Chalancon, B.; Poulet, E.; Leaune, E. Lived Experiences of Suicide Bereavement within Families: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Laitila, A. Longitudinal changes in suicide bereavement experiences: A qualitative study of family members over 18 months after loss. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, A.; Osborn, D.; King, M.; Erlangsen, A. Effects of suicide bereavement on mental health and suicide risk. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, D.L.; Felner, R.D.; Brand, S.; Adan, A.M.; Evans, E.G. A Prospective Study of Life Stress, Social Support, and Adaptation in Early Adolescence. Child Dev. 1992, 63, 542–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, R.; Ortin, A.; Scott, M.; Shaffer, D. Characteristics of suicidal ideation that predict the transition to future suicide attempts in adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 1288–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.X.; Chen, J.M. A study on the relationship between coping style and suicidal ideation in junior high students. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 24, 1402–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, R.; Faria, A.R.; Ribeiro, D.; Picó-Pérez, M.; Bessa, J.M. Structural and functional brain correlates of suicidal ideation and behaviors in depression: A scoping review of MRI studies. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 126, 110799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiksenbaum, L.; Marjanovic, Z.; Greenglass, E.; Garcia-Santos, F. Impact of economic hardship and financial threat on suicide ideation and confusion. J. Psychol. 2017, 151, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, Y.; Oh, W.O.; Suk, M. Risk factors for suicide ideation among adolescents: Five-year national data analysis. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 31, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, X.; Zhu, D.; Gong, X. Cyber-victimization and suicidal ideation in adolescents: A longitudinal moderated mediation model. J. Youth Adolesc. 2023, 52, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oon-Arom, A.; Wongpakaran, T.; Kuntawong, P.; Wongpakaran, N. Attachment anxiety, depression, and perceived social support: A moderated mediation model of suicide ideation among the elderly. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2021, 33, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Xia, T.; Reece, C. Social and individual risk factors for suicide ideation among Chinese children and adolescents: A multilevel analysis. Int. J. Psychol. J. Int. Psychol. 2018, 53, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enătescu, I.; Craina, M.; Gluhovschi, A.; Giurgi-Oncu, C.; Hogea, L.; Nussbaum, L.A.; Bernad, E.; Simu, M.; Cosman, D.; Iacob, D.; et al. The role of personality dimensions and trait anxiety in increasing the likelihood of suicide ideation in women during the perinatal period. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 42, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.J.; Paley, B. Families as systems. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1997, 48, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.J.; Paley, B. Understanding families as systems. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2003, 12, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.F.; Yao, L.S.; Wu, L.; Tian, Y.; Xu, L.; Sun, X.J. Parental phubbing and adolescent problematic mobile phone use: The role of parent-child relationship and self-control. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, T.; Rose, T.; Colombo, G.; Hong, J.S.; Coard, S.I. Family-Level Factors and African American Children’s Behavioral Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Child Youth Care Forum 2015, 44, 819–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurock, R.; Gruchel, N.; Bonanati, S.; Buhl, H.M. Family Climate and Social Adaptation of Adolescents in Community Samples: A Systematic Review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2022, 7, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudge, J.R.; Mokrova, I.; Hatfield, B.E.; Karnik, R.B. Uses and misuses of Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory of human development. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2009, 1, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, S. Inequalities and suicidal behavior. In The International Handbook of Suicide Prevention: Research, Policy and Practice; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 258–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbogen, E.B.; Lanier, M.; Montgomery, A.E.; Strickland, S.; Wagner, H.R.; Tsai, J. Financial strain and suicide attempts in a nationally representative sample of US adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 189, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, M.; Solakoglu, Ö. Strain, negative emotions, and suicidal behaviors among adolescents: Testing general strain theory. Youth Soc. 2019, 51, 638–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirkis, J.; Spittal, M.J.; Keogh, L.; Mousaferiadis, T.; Currier, D. Masculinity and suicidal thinking. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017, 52, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Subiela, X.; Castellano-Tejedor, C.; Villar-Cabeza, F.; Vila-Grifoll, M.; Palao-Vidal, D. Family Factors Related to Suicidal Behavior in Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 1, 9892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Costello, E.J.; Leblanc, W.; Sampson, N.A.; Kessler, R.C. Socioeconomic Status and Adolescent Mental Disorders. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1742–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yin, X.; Jiang, S. Effects of multidimensional child poverty on children’s mental health in Mainland China. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De France, K.; Stack, D.; Serbin, L. Associations between early poverty exposure and adolescent well-being: The role of childhood negative emotionality. Dev. Psychopathol. 2022, 35, 1808–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argabright, S.T.; Tran, K.T.; Visoki, E.; DiDomenico, G.E.; Moore, T.M.; Barzilay, R. COVID-19-related financial strain and adolescent mental health. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2022, 16, 100391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conger, R.D.; Ge, X.; Elder, G.H., Jr.; Lorenz, F.O.; Simons, R.L. Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Dev. 1994, 65, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, L.M.; Collins, J.M.; Cuesta, L. Household debt and adult depressive symptoms in the United States. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2016, 37, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corman, H.; Curtis, M.A.; Noonan, K.; Reichman, N.E. Maternal depression as a risk factor for children’s inadequate housing conditions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 149, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, A.; Allen, J.; Alpass, F.; Stephens, C. Longitudinal trajectories of quality of life and depression by housing tenure status. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2018, 73, e165–e174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Beck, J.S.; Newman, C.F. Hopelessness, depression, suicidal ideation, and clinical diagnosis of depression. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 1993, 23, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.; Yu-Chin, M.; Yu-Chuan, L.; Jin-Ling, J.; Mei-Hui, W.; Kuo-Cheng, C. The relationship between depressive symptoms, rumination, and suicide ideation in patients with depression. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chioqueta, A.P.; Stiles, T.C. Personality traits and the development of depression, hopelessness, and suicide ideation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2005, 38, 1283–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Jia, X.; Lin, D.; Liu, X. Stressful Life Events, Depression, and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Among Chinese Left-Behind Children: Moderating Effects of Self-Esteem. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollust, S.E.; Eisenberg, D.; Golberstein, E. Prevalence and correlates of self-injury among university students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2008, 56, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwangi, C.; Karanja, S.; Gachohi, J.; Wanjihia, V.; Zipporah, N. Depression, injecting drug use, and risky sexual behavior syndemic among women who inject drugs in Kenya: A cross-sectional survey. Harm Reduct. J. 2019, 16, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabinowitz, J.A.; Jin, J.; Kahn, G.D.; Kuo, S.I.; Campos, A.I.; Rentería, M.E.; Benke, K.; Wilcox, H.C.; Ialongo, N.S.; Maher, B.S.; et al. Genetic propensity for risky behavior and depression and risk of lifetime suicide attempt among urban African Americans in adolescence and young adulthood. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2021, 186, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisch, J.; Leino, E.V.; Silverman, M.M. Aspects of suicidal behavior, depression, and treatment in college students: Results from the Spring 2000 National College Health Assessment Survey. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2005, 35, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buxbaum, O. The S-O-R-Model. In Key Insights into Basic Mechanisms of Mental Activity; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiades, M.H.; Kapoor, S.; Wootten, J.; Lamis, D.A. Perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation in undergraduate women with varying levels of mindfulness. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2016, 20, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, A.; Kelly, P.; Goodwin, J.; Behan, L. Depressive Symptoms and Suicidal Ideation among Irish Undergraduate College Students. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 39, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K.; Green, J.G.; Hwang, I.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Sampson, N.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Kessler, R.C. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. Attachment in Adulthood: Structure, Dynamics, and Change, 2nd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S. Object relations, dependency, and attachment: A theoretical review of the infant-mother relationship. Child Dev. 1969, 40, 969–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- VanBakel, H.J.A.; Hall, R.A.S. Parent–Child Relationships and Attachment. In Handbook of Parenting and Child Development across the Lifespan; Sanders, M., Morawska, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranson, K.E.; Urichuk, L.J. The effect of parent–child attachment relationships on child biopsychosocial outcomes: A review. Early Child Dev. Care 2008, 178, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blessing, A.; Russell, P.D.; DeBeer, B.B.; Morissette, S.B. Perceived Family Support Buffers the Impact of PTSD-Depression Symptoms on Suicidal Ideation in College Students. Psychol. Rep. 2023, 00332941231175358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babore, A.; Trumello, C.; Candelori, C.; Paciello, M.; Cerniglia, L. Depressive symptoms, self-esteem and perceived parent–child relationship in early adolescence. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasmin, B.Z.; Anat, B.K. Attachment to parents as a moderator in the association between sibling bullying and depression or suicidal ideation among children and adolescents. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarnaghash, M.; Zarnaghash, M.; Zaenaghash, N. The Relationship between Family Communication Patterns and Mental Health. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 84, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Skay, C.; Sieving, R.; Naughton, S.; Bearinger, L.H. Family and racial factors associated with suicide and emotional distress among Latino students. J. Sch. Health 2008, 78, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlberg, J.A.; Peña, J.B.; Zayas, L.H. Familism, parent-adolescent conflict, self-esteem, internalizing behaviors and suicide attempts among adolescent Latinas. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2010, 41, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.P.; Li, D.P.; Zhang, W. Adolescence’s Family Difficulty and Social Adaptation: Coping efficacy of compensatory, mediation, and moderation effects. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. Soc. Sci. 2010, 220, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Q.; Song, S.G. Ego Identity, Parental Attachment and Causality Orientation in University Students. Stud. Psychol. Behav. 2012, 10, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.; Wang, K.; Zhu, Y.; Luo, X.; Yang, Z. Norm of The Depression Self-rating Scale for Children in Chinese Urban Children. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2003, 17, 547–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.Y.; Wang, D.B.; Wu, S.Q.; Yea, J.H. Self-rating Scale for Suicidal Ideation. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2002, 12, 36–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. PROCESS: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling [White Paper]. 2012. Available online: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Liu, X.; Tein, J.Y. Life events, psychopathology, and suicidal behavior in Chinese adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 86, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Peng, C.; Guo, Y.; Cai, Z.; Yip, P.S.F. Mechanisms connecting objective and subjective poverty to mental health: Serial mediation roles of negative life events and social support. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, K.C.; Bi, Y.; Borden, L.A.; Reinke, W.M. Latent classes of psychiatric symptoms among Chinese children living in poverty. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2012, 21, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadsworth, M.E.; Achenbach, T.M. Explaining the link between low socioeconomic status and psychopathology: Testing two mechanisms of the social causation hypothesis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 73, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbogen, E.B.; Molloy, K.; Wagner, H.R.; Kimbrel, N.A.; Beckham, J.C.; Van Male, L.; Bradford, D.W. Psychosocial protective factors and suicidal ideation: Results from a national longitudinal study of veterans. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 260, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, L.; Chi, I. Factors related to Chinese older adults’ suicidal thoughts and attempts. Aging Ment. Health 2016, 20, 752–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.; Nam, S.J. Multidimensional poverty among different age cohorts in South Korea. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2022, 31, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waraan, L.; Siqveland, J.; Hanssen-Bauer, K.; Czjakowski, N.O.; Axelsdóttir, B.; Mehlum, L.; Aalberg, M. Family therapy for adolescents with depression and suicidal ideation: A systematic review and meta–analysis. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 831–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, I.S.; Horwood, L.J.; Fergusson, D.M. Childhood anxiety/withdrawal, adolescent parent–child attachment and later risk of depression and anxiety disorder. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2012, 21, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.P.; Marsh, P.; McFarland, C.; McElhaney, K.B.; Land, D.J.; Jodl, K.M.; Peck, S. Attachment and autonomy as predictors of the development of social skills and delinquency during midadolescence. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 70, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abela, J.R.Z.; Hankin, B.L.; Haigh, E.A.P.; Adams, P.; Vinokuroff, T.; Trayhern, L. Interpersonal vulnerability to depression in high-risk children: The role of insecure attachment and reassurance seeking. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2005, 34, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.A.; Overholser, J.C.; Spirito, A. Stressful life events associated with adolescent suicide attempts. Can. J. Psychiatry 1994, 39, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spruit, A.; Goos, L.; Weenink, N.; Rodenburg, R.; Niemeyer, H.; Stams, G.J.; Colonnesi, C. The relation between attachment and depression in children and adolescents: A multilevel meta-analysis. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 23, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dardas, L.A. Family functioning moderates the impact of depression treatment on adolescents’ suicidal ideations. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2019, 24, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, F.; Mota, C.P. Parenting styles and suicidal ideation in adolescents: Mediating effect of attachment. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 734–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zortea, T.C.; Gray, C.M.; O’Connor, R.C. The relationship between adult attachment and suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A systematic review. Arch. Suicide Res. 2021, 25, 38–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S.; Chin, C.A.; Meyer, E.W.; Sust, S.; Chu, J. Asian American adolescent help-seeking pathways for psychological distress. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2022, 13, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived family financial stress | 1.36 (0.56) | - | |||

| 2. Suicidal ideation | 0.32 (0.20) | 0.17 *** | - | ||

| 3. Depression | 0.79 (0.23) | 0.18 *** | 0.69 *** | - | |

| 4. Parent–child attachment | 3.62 (0.65) | −0.16 *** | −0.45 *** | −0.50 *** | - |

| Regression Equation | Fit Index | Regression Coefficients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variables | Predictors | R | R2 | F | β | t |

| Depression | Perceived family financial stress | 0.33 | 0.11 | 19.59 | 0.07 | 4.76 *** |

| Suicidal ideation | Perceived family financial stress | 0.72 | 0.52 | 94.10 | 0.01 | 0.92 |

| Depression | 0.55 | 15.66 *** | ||||

| Parent attachment | −0.04 | −3.33 *** | ||||

| Depression × Parent–child attachment | −0.13 | −3.07 ** | ||||

| Level of Parent Attachment | Indirect Effects | Boot SE | 95% Bootstrap Lower Limit | 95% Bootstrap Upper Limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M − SD | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.07 |

| M | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| M + SD | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Wu, H.; Huang, B.; Zhang, C.; Niu, G. The Association between Perceived Family Financial Stress and Adolescent Suicide Ideation: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 948. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110948

Yang Q, Zhang W, Wu H, Huang B, Zhang C, Niu G. The Association between Perceived Family Financial Stress and Adolescent Suicide Ideation: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(11):948. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110948

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Qi, Wenyu Zhang, Huan Wu, Baozhen Huang, Chenyan Zhang, and Gengfeng Niu. 2023. "The Association between Perceived Family Financial Stress and Adolescent Suicide Ideation: A Moderated Mediation Model" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 11: 948. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110948

APA StyleYang, Q., Zhang, W., Wu, H., Huang, B., Zhang, C., & Niu, G. (2023). The Association between Perceived Family Financial Stress and Adolescent Suicide Ideation: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences, 13(11), 948. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110948