Intergroup Contact Is Associated with Less Negative Attitude toward Women Managers: The Bolstering Effect of Social Dominance Orientation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Effect of Intergroup Contact on Individual Differences

1.2. Social Dominance Orientation and Intergroup Contact toward Women Manager

1.3. The Present Research

2. Method

2.1. Sample Size Determination

2.2. Participants, Design, and Procedure

2.3. Measures

3. Results

3.1. Analytical Strategy

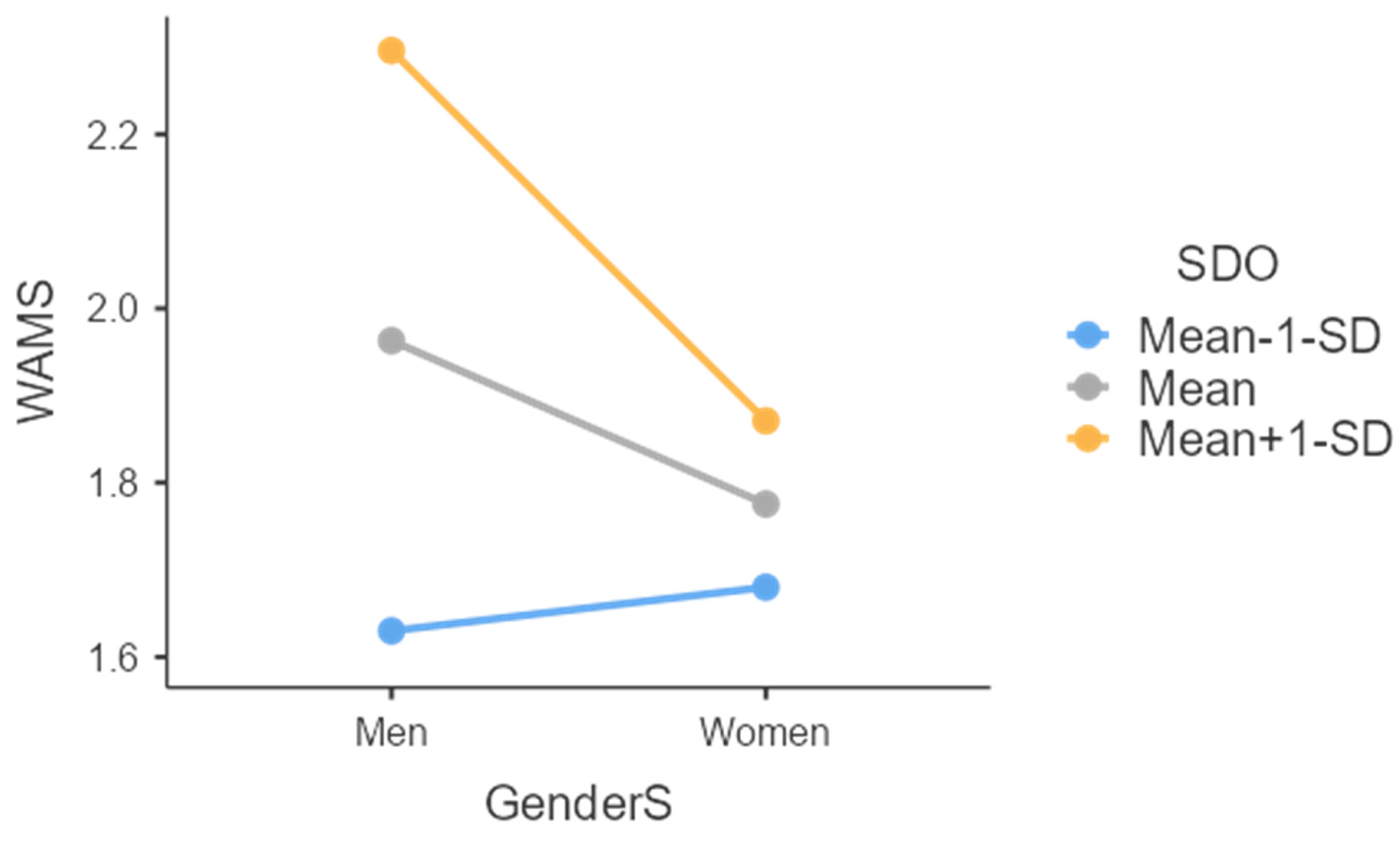

3.2. SDO and Attitudes toward Women as Managers: The Moderating Role of Superiors’ Gender

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Contu, F.; Ellenberg, M.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Pantaleo, G.; Pierro, A. Need for cognitive closure and desire for cultural tightness mediate the effect of concern about ecological threats on the need for strong leadership. Curr. Psychol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, M.J.; Lorente, R. Threat, tightness, and the evolutionary appeal of populist leaders. In The Psychology of Populism; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 276–294. [Google Scholar]

- Carton, A.M.; Rosette, A.S. Explaining bias against black leaders: Integrating theory on information processing and goal-based stereotyping. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 1141–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.; Glass, C. Glass cliffs and organizational saviors: Barriers to minority leadership in work organizations. Soc. Probl. 2013, 60, 168–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M.L.; Keeves, G.D.; Westphal, J.D. One step forward, one step back: White male top manager organizational identification and helping behavior toward other executives following the appointment of a female or racial minority CEO. Acad. Manag. J. 2018, 61, 405–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosette, A.S.; Livingston, R.W. Failure is not an option for Black women: Effects of organizational performance on leaders with single versus dual-subordinate identities. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 1162–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsesser, K.M. Gender bias against female leaders: A review. In Handbook on Well-Being of Working Women; Connerley, M.L., Wu, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, A.M.; Eagly, A.H.; Mitchell, A.A.; Ristikari, T. Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 616–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javalgi, R.R.G.; Scherer, R.; Sánchez, C.; Pradenas Rojas, L.; Parada Daza, V.; Hwang, C.E.; Yan, W. A comparative analysis of the attitudes toward women managers in China, Chile, and the USA. Int. J. Bus. Emerg. 2011, 6, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalyst Quick Take: Statistical Overview of Women in the Workplace. Available online: http://www.catalyst.org/knowledge/statistical-overview-women-workplace (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- U.S. Women in Business. Available online: http://www.catalyst.org/publication/132/us-women-in-business (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Pratto, F.; Sidanius, J.; Stallworth, L.M.; Malle, B.F. Social Dominance Orientation: A Personality Variable Predicting Social and Political Attitudes. J. Pers. Soc. Psych. 1994, 67, 741–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G. The Nature of Prejudice; Reading, M.A., Ed.; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Albarello, F.; Mula, S.; Contu, F.; Baldner, C.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Pierro, A. Addressing the effect of concern with COVID-19 threat on prejudice towards immigrants: The sequential mediating role of need for cognitive closure and desire for cultural tightness. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2023, 93, 101755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarello, F.; Contu, F.; Baldner, C.; Vecchione, M.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Pierro, A. At the roots of Allport’s “prejudice-prone personality”: The impact of NFC on prejudice towards different outgroups and the mediating role of binding moral foundations. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2023, 97, 101885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, A.N.; Wojda, M.R. Social Dominance Orientation, Right-Wing Authoritarianism, Sexism, and Prejudice toward Women in the Workforce. Psychol. Wom. Quart. 2008, 32, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, R.J.; Turner, R.N. Can imagined interactions produce positive perceptions?: Reducing prejudice through simulated social contact. Am. Psychol. 2009, 64, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, R.J.; Turner, R.N. The imagined contact hypothesis. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Olson, J.M., Zanna, M.P., Eds.; Academic Press: Orlando, FL, USA, 2012; Volume 46, pp. 125–182. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, S.C.; Aron, A.; McLaughlin-Volpe, T. The extended contact effect: Knowledge of cross-group friendships and prejudice. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, D.; Swamy, R. Attitudes toward women as managers: Does interaction make a difference? Hum. Relat. 1995, 48, 1285–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duehr, E.E.; Bono, J.E. Men, women, and managers: Are stereotypes finally changing? Pers. Psychol. 2006, 59, 815–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoker, J.I.; Van der Velde, M.; Lammers, J. Factors relating to managerial stereotypes: The role of gender of the employee and the manager and management gender ratio. J. Bus. Psychol. 2012, 27, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhont, K.; Van Hiel, A. Direct contact and authoritarianism as moderators between extended contact and reduced prejudice: Lower threat and greater trust as mediators. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2011, 14, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, G. Do ideologically intolerant people benefit from intergroup contact? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 20, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, A.W. The Psychology of Closed Mindedness; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dhont, K.; Roets, A.; Van Hiel, A. Opening closed minds: The combined effects of intergroup contact and need for closure on prejudice. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 37, 514–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roets, A.; Van Hiel, A. The role of need for closure in essentialist entitativity beliefs and prejudice: An epistemic needs approach to racial categorization. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 50, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, G. The puzzling person-situation schism in prejudice-research. J. Res. Pers. 2009, 43, 247–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, M.; Baldner, C.; Pierro, A. How and when need for cognitive closure impacts attitudes towards women managers (Cómo y cuándo la necesidad de cierre influye en las actitudes hacia las mujeres directivas). Int. J. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 38, 157–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldner, C.; Pierro, A.; Di Santo, D.; Kruglanski, A.W. Men and women who want epistemic certainty are at-risk for hostility towards women leaders. J. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 162, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidanius, J.; Pratto, F. Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Aiello, A.; Tesi, A. “Does This Setting Really Fit with Me?”: How Support for Group-based Social Hierarchies Predicts a Higher Perceived Misfit in Hierarchy-attenuating Settings. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol 2023, 53, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.-C.; Pratto, F.; Johnson, B.T. Intergroup Consensus/Disagreement in Support of Group-Based Hierarchy: An Examination of Socio-Structural and Psycho-Cultural Factors. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 1029–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratto, F.; Sidanius, J.; Levin, S. Social Dominance Theory and the Dynamics of Intergroup Relations: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psych. 2006, 17, 271–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesi, A.; Pratto, F.; Pierro, A.; Aiello, A. Group Dominance in Hierarchy-Attenuating and Hierarchy-Enhancing Organizations: The Role of Social Dominance Orientation, Need for Cognitive Closure, and Power Tactics in a Person–Environment (Mis)Fit Perspective. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2020, 24, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratto, F.; Stewart, A.L. Group Dominance and the Half-Blindness of Privilege. J. Soc. Iss. 2012, 68, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.K.; Sidanius, J.; Kteily, N.; Sheehy-Skeffington, J.; Pratto, F.; Henkel, K.E.; Foels, R.; Stewart, A.L. The Nature of Social Dominance Orientation: Theorizing and Measuring Preferences for Intergroup Inequality Using the New SDO Scale. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 109, 1003–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, D.E.J.; Jackson, M. Benevolent and Hostile Sexism Differentially Predicted by Facets of Right-Wing Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation. Pers. Ind. Diff. 2019, 139, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibley, C.G.; Wilson, M.S.; Duckitt, J. Antecedents of Men’s Hostile and Benevolent Sexism: The Dual Roles of Social Dominance Orientation and Right-Wing Authoritarianism. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 33, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T.F.; Tropp, L.R. A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 751–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauff, M.; Schmid, K.; Lolliot, S.; Al Ramiah, A.; Hewstone, M. Intergroup Contact Effects via Ingroup Distancing among Majority and Minority Groups: Moderation by Social Dominance Orientation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kteily, N.S.; Hodson, G.; Dhont, K.; Ho, A.K. Predisposed to Prejudice but Responsive to Intergroup Contact? Testing the Unique Benefits of Intergroup Contact across Different Types of Individual Differences. Group Process. Amp. Intergroup Relat. 2017, 22, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, K.; Hewstone, M.; Küpper, B.; Zick, A.; Wagner, U. Secondary Transfer Effects of Intergroup Contact. Soc. Psychol. Quart. 2012, 75, 28–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, S.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Faul, F. A short tutorial of GPower. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2007, 3, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, A.; Passini, S.; Tesi, A.; Morselli, D.; Pratto, F. Measuring Support For Intergroup Hierarchies: Assessing The Psychometric Proprieties of The Italian Social Dominance Orientation 7 Scale. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 26, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, L.H. Women as managers scale. In Handbook of Tests and Measurement in Education and the Social Sciences; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2000; p. 306. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Asbrock, F.; Christ, O.; Duckitt, J.; Sibley, C.G. Differential Effects of Intergroup Contact for Authoritarians and Social Dominators. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 38, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantaleo, G.; Contu, F. The dissociation between cognitive and emotional prejudiced responses to deterrents. Psychol. Hub. 2021, 38, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesi, A.; Aiello, A.; Pratto, F. How People Higher on Social Dominance Orientation Deal with Hierarchy-Attenuating Institutions: The Person-Environment (Mis)Fit Perspective in the Grammar of Hierarchies. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 42, 26721–26734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, A.; Tesi, A.; Pratto, F.; Pierro, A. Social Dominance and Interpersonal Power: Asymmetrical Relationships within Hierarchy-enhancing and Hierarchy-attenuating Work Environments. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 48, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A.G.; Poehlman, T.A.; Uhlmann, E.L.; Banaji, M.R. Understanding and Using the Implicit Association Test: III. Meta-Analysis of Predictive Validity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| SDO | GenderS | WAMS | GEND | POLITIC | AGE | M(SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDO | −0.87 | 1.21(0.97) | |||||

| GenderS | −0.06 | - | - | ||||

| WAMS | 0.395 *** | −0.180 * | −0.89 | 1.85(0.64) | |||

| GEND | −0.151 | 0.365 *** | −0.177 * | - | - | ||

| POLITIC | 0.248 ** | −0.083 | 0.167 * | −0.154 | - | 3.57(1.53) | |

| AGE | −0.036 | 0.055 | 0.075 | −0.155 | 0.208 * | - | 32.8(28.0) |

| EDU | 0.044 | 0.202 * | −0.071 | 0.251 ** | −0.123 | −0.069 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Contu, F.; Tesi, A.; Aiello, A. Intergroup Contact Is Associated with Less Negative Attitude toward Women Managers: The Bolstering Effect of Social Dominance Orientation. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 973. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13120973

Contu F, Tesi A, Aiello A. Intergroup Contact Is Associated with Less Negative Attitude toward Women Managers: The Bolstering Effect of Social Dominance Orientation. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(12):973. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13120973

Chicago/Turabian StyleContu, Federico, Alessio Tesi, and Antonio Aiello. 2023. "Intergroup Contact Is Associated with Less Negative Attitude toward Women Managers: The Bolstering Effect of Social Dominance Orientation" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 12: 973. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13120973

APA StyleContu, F., Tesi, A., & Aiello, A. (2023). Intergroup Contact Is Associated with Less Negative Attitude toward Women Managers: The Bolstering Effect of Social Dominance Orientation. Behavioral Sciences, 13(12), 973. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13120973