Abstract

By employing a thematic review of 74 relevant publications and our learning, teaching, and research experiences and expertise, we discussed the concepts of ‘reflexivity’, ‘sensitivity’ and ‘integrity’, and the factors that enhance or hinder their practice. We also categorized the levels of sensitivity according to the stages of conducting and interpreting interviews in qualitative research. By categorizing the three levels of sensitivity ‘i.e., high sensitivity during interviewing, higher sensitivity during transcribing data, and highest sensitivity and criticality during interpreting data’ with practical examples, we offer an approach that facilitates and supports the application of ethical interviews. We conclude that achieving sensitivity and reflexivity enhances the trustworthiness of the overall research and reflects the application of research ethics and integrity in practice.

1. Introduction

The rapid increase in the number of qualitative publications in almost all disciplines reflects the trustworthiness and robustness of the research methodology on the one hand, and the need for strengthening specific skills on the other. Among others, the focus is on critical thinking, interview construction and conduct, interaction, data analysis, synthesis, and interpretational skills.

In qualitative research, researchers develop interview guides that help collect in-depth data from research participants. In the conduct of interviews, researchers attempt to exercise empathy, transparency, and unconditional positivity to create an interviewing space [1,2] and interpersonal connection that allows them to establish a good rapport with participants [3]. However, there are moments when either interviewers or interviewees feel that something is not going well in their interaction. This might be attributed to the topic under discussion, which can be sensitive and demands many reflexive experiences on the part of interviewees. This, of course, demands the expertise of inquirers when dealing with sensitive topics.

The previous literature has attempted to differentiate between several types of reflexivity, including the interaction of the researcher with the social world, the sociology of knowledge, publishing and research politics, and using subjectivity to understand the social and psychological world [4]. Despite the trend toward developing a reflexive research paradigm, particularly in the social sciences [5], these benefits of practicing reflexivity have been critiqued for inflating the significance of reflexivity in research or its role in research as a methodological tool [6]. Given the importance of reflexivity in interviewing, researchers have long criticized the dominance of neo-positivism and romanticism paradigms in interviewing [7], and have advocated for the use of interviews as a means of interaction between the interviewer and the interviewee [8]. When researchers misuse reflexivity to selectively extract what serves their aims and fits their beliefs while ignoring the rest of the transcript, this is a tempting interpretation [9]. This argument was also addressed in another study seeking to demonstrate the difference between verbal interview and a verbatim transcript, and its influence on readers.

These days, there is a need to examine moral accountability and apply more practical ways of analyzing and reporting interviews that include more than just selecting specific phrases to address the researcher’s concerns [10]. In this setting, the researcher advocated for more participatory interview interpretation and presentation [11]. This viewpoint is backed up by initiative calls supporting hermeneutic approaches to conduct more meaningful interviews [12]. One idea to help with this stage is to integrate visual and textual information, allowing the researcher to be more reflexive while conducting, interpreting, and utilizing interview results [13]. Given the long debate over what constitutes reflexivity in interviewing and how reflexivity can increase sensitivity in interviews, what matters most is that researchers remain involved in these existing methodological tools [14], in order to gain a deeper understanding and improve their skills in conducting interviews [15] in real-life situations.

Dealing with participants in real-life situations and collecting an abundant number of words demand qualitative researchers to be reflexive and sensitive. In critical qualitative research, the concept of sensitivity is under-researched. Further, the concept of reflexivity differs from one field to another. We believe that the ethical application of both ‘sensitivity and reflexivity’ demands the practice of ‘integrity’. While there are publications on ‘reflexivity in qualitative studies’, there is a lack of studies on ‘sensitivity in qualitative studies’, interviews in particular, or how ‘integrity’ interrelates to the concepts of ‘sensitivity and reflexivity’. As a result, this paper attempts to answer these research questions: (1) What do ‘reflexivity, sensitivity and integrity’ mean in interviews? and (2) How do they interrelate in conducting interviews? Below we report the research procedures and methods.

2. Research Design and Methods

We assume that undergraduates, graduates, postgraduates and even academics could achieve a higher level of quality in qualitative research if they are equipped with the sufficient awareness and understanding of interviewees’ needs, interests, and preferences, that is, sensitivity. Further, we contend that this first step could proceed when they are transparent and reflexive, that is, reflexivity. Not only should they be sensitive and reflexive in interviewing, but they should also believe in research ethics and possess integrity, that is, moral development. Given this, we believe that these three work interactively to achieve quality conduct in interviews. It is significant that researchers need to consider conducting qualitative research that contributes to human development with humane, honest, practical, and professional practices.

The thematic analysis technique is useful for reducing researchers’ biases [16], and provides a systematic and thorough analysis of the examined topic [17]. Therefore, we employed the thematic analysis technique because the study integrates the researchers’ profound academic experiences in qualitative research and teaching undergraduate and graduate students, as well as a critical review of previous studies concerning sensitivity and reflexivity in interviewing.

The reviewed literature included publications (articles, book chapters and books), using the English language. We used several databases to explore relevant studies (ScienceDirect, Sage, Web of Science, and Scopus). The starting date was determined using the oldest available papers relevant to the study, and the ending date was determined using the day of the search. Because reflexivity is applied in all topic areas, all subject areas were considered. We used following terms in our search:

- Title contains sensitivity in qualitative research

- OR contains sensitivity in research

- OR contains reflexivity in research

- OR contains reflexivity in qualitative research

- OR contains sensitivity and reflexivity in qualitative research

- OR contains sensitivity and reflexivity in research

- OR contains adult moral development

We added ‘adult moral development’ in our search keywords because we indicated that researchers might interview with sensitivity, while exercising reflexivity and contemplating integrity. The search resulted in 263 hits, of which 74 were included for review purposes. The rest were excluded due to their irrelevance to the questions of the study, not mentioning any of these targeted themes, or discussing them from different perspectives or contexts. Our list of references shows both the used and cited ones; those with an asterisk (*) refer to the one not used for review purposes.

In this thematic review, we established ‘trustworthiness’ by following four psychometric concepts: credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Table 1 details the following techniques used to enhance credibility, facilitate transferability decisions, audit confirmability, and check dependability.

Table 1.

Techniques used to achieve trustworthiness.

3. Findings

In this section, we discuss the main themes and subthemes. Further, we highlight how interviewing with sensitivity by exercising reflexivity, while considering integrity, are interrelated.

3.1. Reflexivity in Interviewing

Reflexivity technically refers to the exercise of transparency in interviewing and “promotes an intuition-informed decision-making process as a means to achieve ethical practice and conduct interviews with sensitivity and proficiency” [26] (p. 747). Because reflexivity reflects the attainment of research ethics and quality, some researchers might practice uncomfortable reflexivity instead [27]. Below, we present a synthesis of reflexivity and how qualitative researchers can be sensitive by exercising reflexivity.

3.1.1. Defining Reflexivity

In lexicography, reflexivity is defined as “the fact of someone being able to examine his or her feelings, reactions, and motives…reasons for acting… and how these influence what he or she does or thinks in a situation” [28]. The technical meaning of this concept is not significantly different from the lexical meaning. In particular, the lexeme ‘reflexive’ originated from the theory of Coordinated Management of Meaning (CMM). Cronen and Pearce as cited in [29] introduced the CMM, which assumes that regulative and constitutive rules control human interaction. These rules interact reflexively to form meaningful human interactions. Building upon this theory, two other reflexivity types are generated: the strange and reflexive loops. While the former indicates a change in meaning, the other indicates stillness in meaning [30]. The same author proposed four questions to achieve effective interventive interviewing: lineal, circular, strategic, and reflexive. These affect the interviewer and interviewee(s): conservative, liberating, constraining, and generative effects. They also have different purposes, including explaining problems, behavior, leading and confrontation, and hypothetical future and perspective questions [29]. Regardless of all this conceptualization, the general meaning of reflexivity in interviewing relates to “reflecting on the speaker’s narrative, expressing the interviewer’s understanding of it” [31] (p. 3).

While reflexivity decreases subjectivity in conducting interviews [32], the use of the ‘reflexivity’ concept remains dissimilar according to the context and field of study: political and forensic science [33], health care and midwifery practice [34], supervisor–supervisee relationship [35], interviewing offenders [36], and indicating truth in the literature [37]. Most interestingly, some researchers in the field of psychology use psychoanalysis to reach the unconscious processes and gain knowledge from interviewing [38]. The concept of reflexivity in interviewing extends to folklore research [39], clinical psychology [40], surgery [41], and erotic reflexivity in sociology, where these emotions make the collected data more informative and productive [42].

3.1.2. A Brief Debate on Reflexivity

The practice of reflexivity is the essence of learning to conduct quality qualitative research [43]. With reflexivity, we understand the value of all the participating members in the research, including the researcher, interviewer, interviewees, society, and the surrounding environment and context [44]. However, some researchers have fashionably used it to claim trustworthiness [45], and the evidence concerning reaching reflexivity is still variable. For instance, some researchers argue that the use of audio and visual aids urges the interviewees to emphasize their identity, enhancing reflexivity [46]. There is also an argument that awareness of the difference between contextual and cognitive interests is the path to producing more reliable knowledge using interviews. This argument attempts to distinguish between the society as a whole and the researchers—making and creating knowledge [47]. Above all, we argue that ‘reflexivity’ is an ongoing part of the research process and is a tool that aids in enhancing the interpretation of the data.

The most debatable issue concerning qualitative research is ‘subjectivity’ [48]. The direct interference, and the interviewer’s influence and interpretation of data might reflect questionable reflexivity; we assume that practicing sensitivity helps bridge this gap by increasing the trustworthiness of the investigated knowledge. However, subjectivity is a plus when merged with the examined object or problem (i.e., objectivity) [49], and when merged with the expertise of the researcher to use the data [50]. Researchers argue that there is a possibility for the occurrence of both subjectivity and objectivity in interviewing; a complete picture of the investigated phenomenon can be better seen through this mixture of being subjective and objective during interviewing, transcribing, and interpreting [51].

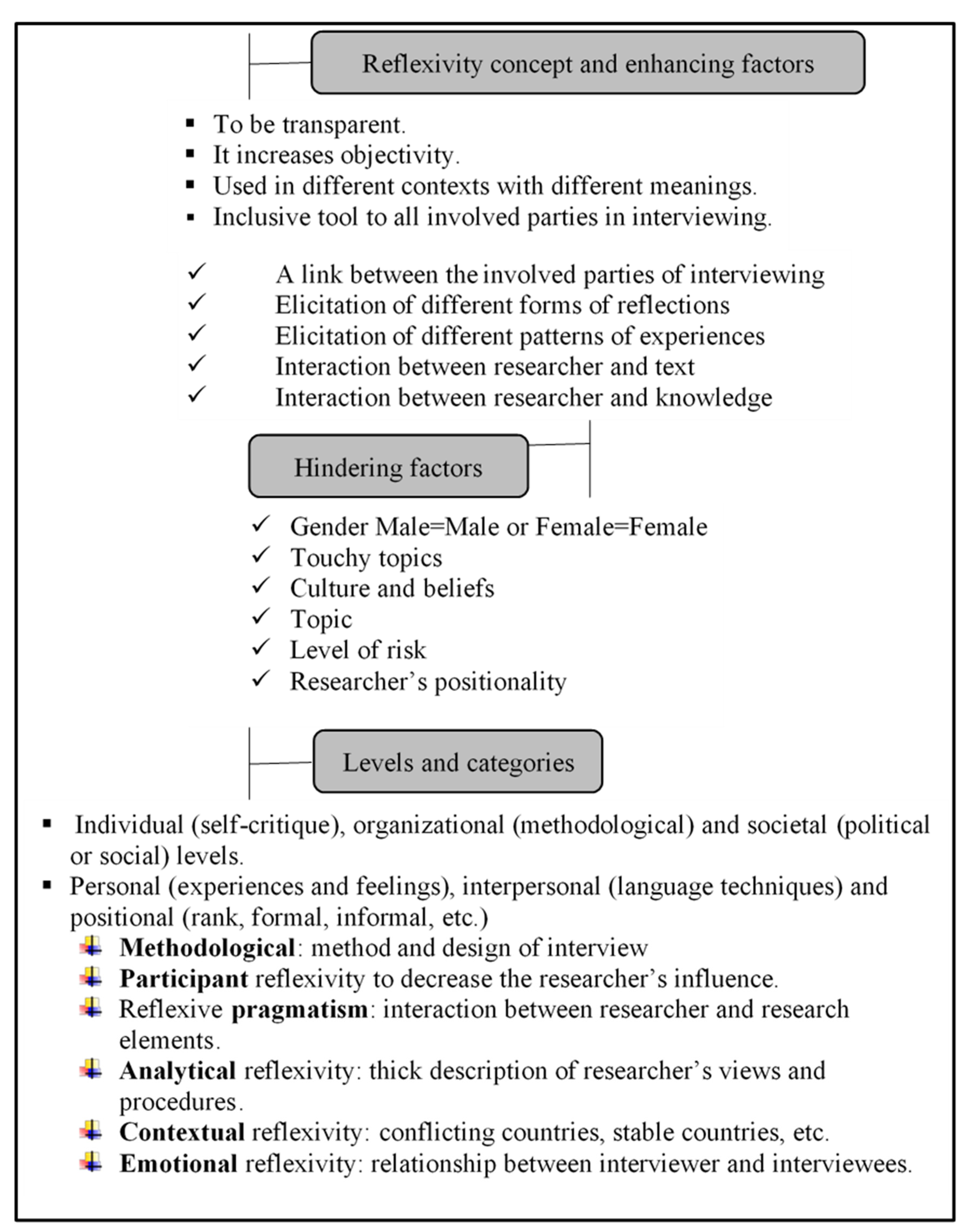

3.1.3. Factors Enhancing and/or Hindering Reflexivity

Linking the interviewer, interviewees and the society to build up a social world [52] is a factor for enhancing reflexivity. The elicitation of prospective and retrospective reflections over time [53], writing about the personification while conducting research [54], the embodiment of the experiences of the researcher [55], and the interactions among the interviewer, interviewees, and context [56] are all factors that enhance reflexivity. The interaction between the researcher’s body and speech is also influential during interviewing [57]. Moreover, using different categories of knowledge (for example, experiential, clinical, cultural, and academic) strengthens the interview interaction [58]. Additionally, the bioecological systems theory considers space and time as reflexivity. In other words, the geographic location (macro-level) and the immediate surroundings (micro-level) are two factors that can improve the interview quality. Time, be it past, present, or future, improves the interview process even during the transcription and interpretation processes [36].

It is also possible that other factors hinder reaching reflexivity in interviewing. Such factors relate to, for example, touchy topics (e.g., intimacy) [57], losing the focus of the researched topic while interviewing and/or interpretation [32], and the researcher’s values, beliefs, experiences, and interests [59]. Other factors could be the nature of the topic itself, the level of the risk (e.g., the low-risk issue of rural living, gender, the high-risk case of alcohol use), and the trait of the interviewer (e.g., neutrality, self-disclosure) [60]. Further, the researcher’s positionality, be it static or fixed, insider or outsider, contributes either negatively or positively to the reflexivity of the interviewing process [61].

3.1.4. Levels and Categories of Reflexivity in Interviewing

Several researchers have attempted to create a three-level typology of ‘micro, meso, and macro’ levels, which are applicable at the individual, organizational, and societal levels. The use of these three levels leads to three types of reflexivity: self-critique, objective and methodological, and political or social [62]. Furthermore, there are three levels of talk during interviews: personal, interpersonal, and positional. While the personal level focuses on the participant’s specific, unique experiences and feelings, the interpersonal level considers the use of words, images, or metaphors, and how the interviewer and interviewee jointly construct the narrative. How people position themselves in the subject and what they talk about refers to the positional level [63] (p. 238).

While reflexivity in research methods and designs of interviewing is known as methodological reflexivity [40], we have found several other categories of reflexivity. For example, participant reflexivity, as a significant factor in decreasing the interviewer’s subjectivity [64], helps achieve trustworthiness in interviewing [65]. Additionally, participant reflexivity is more credible when using dialogic interviewing; this is supported by three strategies: probing questions (i.e., seeking deeper insights), participants’ reflections (discussing interviews, transcript, interpretation, and even findings with the participants), and counterfactual prompting (leading the participants towards a different perspective of thinking) [66]. The more the participants are engaged, the more the trustworthiness is reachable [67].

Another category is reflexive pragmatism; it is achieved by the “interplay between research design and research questions, interviewing and written product” through “the relationship between epistemology and method” [68] (p. 610). A further category is analytical reflexivity, which requires a thick description of all the processes and factors motivating the researcher to decide or conclude on the searched topic [69]. Moreover, the form of language, be it direct speech, reported speech, or enacted scenes, is also vital in establishing analytical reflexivity in interviewing [70].

Researchers in developed and stable countries face different types of challenges while conducting interviews. They, in best cases, view reflexivity as a procedure [71]. Because of the importance of the relationship between the researcher and the participants, and because the feelings of both the parties and the context are vital, emotional reflexivity is introduced as an essential category, referring “to the intersubjective interpretation of one’s own and others’ emotions and how they are enacted” [72] (p. 61). We conclude this part with a summary in Figure 1 of the concept of reflexivity, its enhancing factors, hindering factors, and levels.

Figure 1.

A summary of reflexivity in interviewing.

3.2. Defining Sensitivity: Sensitivity vs. Criticality

The concept of sensitivity is used in medical sciences as a statistical measure for evaluating the accuracy of tests with a positive or negative outcome [73]. The measure of sensitivity becomes highly significant for the reliability of the test outcomes. For medical test results, high sensitivity means high reliability, while the opposite is also true.

In qualitative studies, researchers also exercise sensitivity but in a different way and at various levels. The researcher’s sensitivity includes ‘a host of skills that the qualitative researcher employs throughout all phases of the research cycle’ [74] (p. 780). In interviews, and based on our experiences, ‘sensitivity’ is the concept that deals with awareness and an understanding of interviewees’ needs, interests, and preferences. Being aware and understanding is the primary factor in persuading interviewees to conduct interviews and to engage in possible further interviews and observations. Sensitivity also means that a qualitative researcher needs to be careful in selecting words while interviewing or observing participants so that interviewees are not unintentionally offended. It also means that a researcher needs to be caring, especially when exploring issues that reflect the interviewees’ distressful, depressed, or critical situations. In this sense, sensitivity includes the features of awareness, understanding, carefulness, and caring.

We understand ‘criticality’ as being more relevant to the process of thinking. This critical thinking helps qualitative researchers understand texts, written texts in particular. This means that criticality allows researchers to explore the truth of texts (interview transcripts) while interpreting them. It also means that researchers should be qualified to rationally analyze/interpret and synthesize texts and provide logical conclusions. This criticality is, therefore, very important for all qualitative researchers. In short, sensitivity is applied during verbal interactions with participants, while criticality is implemented in analyzing and reporting texts and raw data.

3.3. Levels of Sensitivity While Conducting and Interpreting Interviews

Based on our experiences, we present the three primary levels of sensitivity concerning conducting and interpreting interviews.

3.3.1. High sensitivity: During Interviewing

During the verbal interactions with interviewees, in order to invite them for interviews and during the interviews, qualitative researchers need to have a high level of sensitivity, meaning that interviewers should pay attention to the interviewees’ words, facial expressions, and body gestures, and note them down. It also means that interviewers listen to the (audio-recorded) interactions of the interviewees as a unit, and write some notes regarding information that needs further investigations/questioning.

In in-depth interviews, follow-up questions (probes) derived from the answers of interviewees will occur. High sensitivity in this stage helps the continuity of the interaction in an exciting and rich data-obtaining manner. Showing a high sensitivity while exploring sensitive issues is also critical. It helps make interviewees feel at ease and ready to continue the interaction with trust.

3.3.2. Higher Sensitivity: Transcribing Data

In transcribing data, qualitative researchers must show higher sensitivity in protecting the anonymity of the participants and their interactions. Higher sensitivity should be applied in transcribing all words verbatim without additions or deletions. In the stage of transcribing data, higher sensitivity also includes profiling every interviewee’s interaction separately and with high confidentiality. In this sense, higher sensitivity application consists of the application of research ethics.

3.3.3. Highest Sensitivity and Criticality: Interpreting Data

In interpreting data, qualitative analysts need to have the highest sensitivity level, which indicates the reading of the entire transcripts of interviewees, the natural selection of participants’ quotes and interpreting them without any bias. In this sense, the implementation of criticality is crucial and cannot be separated from sensitivity. It helps conduct a systematic, logical, and reasonable analysis, synthesis, and interpretation of the transcripts/raw data.

3.3.4. Unconscious Development of Hyper-Sensitivity and Its Consequences

Qualitative researchers need to listen to the words of interviewees carefully and pay attention to the interviewees’ tones and intonations, facial expressions, and body gestures (that clearly or partially imply different meanings) for the sake of grasping a complete understanding of the verbal expression. However, they also need to pay further attention to their own words and behavior. This is important because some interviewers might show unhappy feelings (e.g., anger) toward their participants. Although they might not mean it, this shows a negative behavior that affects the flow of interaction, if it does not lead the participants to refuse to continue being interviewed immediately. Showing unhappy feelings during an interaction with interviewees might be attributed to the lack of training the interviewers have received or the presence of hypersensitivity as part of their personality. Both aspects are not favorable for a qualitative interviewer, who thus needs further training on how to employ a moderate or higher level of sensitivity when collecting or interpreting qualitative data. Training on the correct rise and fall of tones/voices is essential to any interviewer and interviewee. This is because such a tone or pitch change in the voice might be interpreted negatively, leading to ending a conversation.

In academic life, researchers interact with one another formally and/or informally. In both formal and informal situations, they need to be very sensitive towards selecting vocabulary and gestures or facial expressions. The arbitrary use of vocabulary, gestures or facial expressions might force others to react hyper-sensitively. Such incidents might put researchers in critical situations when it comes to collecting data through interviews. This is because hypersensitivity might be developed unconsciously.

Giving a first-hand example by the first author here helps understand hypersensitivity and its consequences. Two colleagues respected each other and used to discuss different topics at different times. One is religious, and the other one is not. It happened that they once started a discussion on a religious topic (the presence of God), which should be discussed with caution; here, careful vocabulary should be used and each should show respect to one another’s views.

- Scholar 1:

- … I watched the debate between you and the other scholar on the presence of God. It was interesting …

- Scholar 2:

- Thank you. You see how that scholar was persistent on the idea of the presence of God … which was insane.

- Scholar 1:

- Insane!? Was it!? Why do you think so?

- Scholar 2:

- … hahaha, it seems that you have the same belief …

- Scholar 1:

- And if I have the same belief?

- Scholar 2:

- (Raising their voice with blushing face) you both go to hell!

- Scholar 1:

- Thank you. Bye for now!

While the discussion initially started well, scholar two’s laughter, the raising of the voice, and the utterance of ‘you both go to hell’ indicate that scholar 2 is not aware of the hyper-sensitivity action they have developed for no apparent reason. Although scholar 2 might attempt to exercise sensitivity when conducting interviews, hyper-sensitivity might appear during their conversation with interviewees, as shown in the above example. Scholar 1 ended the discussion respectfully. The consequence is that they have never discussed any topic since then. Indeed, they might not care for each other anymore. Further, and more seriously, the presence of hypersensitivity affects the reliability of collecting and protecting data, and affects one’s academic and personal life.

By considering our own experiences in conducting interviews, we underscore that conducting more interviews helps enhance researchers’ experiences and expertise, and enhances the application of the appropriate level of sensitivity consciously and unconsciously.

3.4. Integrity

3.4.1. Sensitivity and Integrity

We attempt to relate sensitivity to adult moral development. This includes discussing the acquisition of sensitivity if we believe that it is acquired just as other elements in our life are (e.g., language). It also consists of the learnability of sensitivity if we assume that this element does not exist within our biological and/or developmental system. By doing so, we attempt to establish how the proposed levels of sensitivity in terms of conducting interviews (i.e., conducting, transcribing, and interpreting) and higher education levels (i.e., undergraduate, master, and (post)doctoral) are possibly acquired, learned, or structured, towards more ethical yet credible qualitative research.

When conducting an interview, moral development plays a vital role during the whole research process. Here, sensitivity in research will be a mixture of knowledge of personal ethics, social rules, and even country policies, regulations, and laws. We quote here the concept of ‘ethical sensitivity’ in order to introduce our concept of “qualitative sensitivity.” While ethical sensitivity refers to “the ability to recognize decision situations with ethical content” [75] (p. 361), our concept of ‘qualitative sensitivity’ indicates a researcher’s capacity to make the participants, readers, and involved society well-informed about how we conduct our research, interview our participants, collect and interpret data, and even inferred or reached our final findings.

3.4.2. Teaching and Learning of Research Ethics

Researchers agree about what could be considered questionable or unquestionable research practices [76,77]. These are usually policies, regulations, or laws, individually or collectively, issued by institutions or countries [78]; this is in order to achieve what we call the ‘academic order’ in knowledge production and science advancement.

Given that there is no concrete evidence regarding whether we acquire ethics or learn them, we believe that this is similar to language, which we acquire during our early childhood and when we move to the preschool level and onwards. Previous and current research on teaching ethics and integrity to students indicates that integrity is an independent variable related to personality, but other external factors could still influence it. For instance, a study on teaching ethics to medical students in Croatia indicates that reasoning relates to gender and Machiavellianism [79]. In the context of Turkey, it is reported that although students realize that it is unlawful to cheat, they still practice it [80]. Nevertheless, viewing sensitivity as ethics based on culture and religion is not enough; rules and laws are vital for implementation. This is evident in countries where higher education quality is low and questionable research practices are practiced [81].

Some researchers tend to practice irresponsible research or questionable research practice [82], including “thinking errors, poor coping with research pressures, and inadequate oversight” [83] (p. 320). However, be it an element of ethics, rules, or laws, the teaching of the responsible conduct of research for a researcher [84] should be promoted regardless of the used teaching methods [85]. These could be case study samples [86], active learning, experiential learning or task-based learning [87]. It could start as early as the undergraduate level and be upgraded based on higher education levels, or be promoted in future careers [88].

3.5. The Interrelationship of ‘Sensitivity, Reflexivity, and Integrity’ in Conducting Interviews: Practical Examples

Having introduced each of these three themes separately, we show in Table 2 how these three interact together to allow conducting interviews with higher quality in order to achieve better accountability for qualitative research. We divided the sensitivity levels according to the educational level into three main categories. Next, we provided three possible situations for the three levels of sensitivity when conducting an interview. Each situation shows how a researcher (undergraduate, graduate, or (post)doctorate) interviews, transcribes and interprets data. Criticality, part of sensitivity, is considered during each third level (third, sixth, and ninth). After that, reflexivity is presented, and in each situation, a different category or level of reflexivity is illustrated.

Table 2.

Application of sensitivity levels, reflexivity, and moral development with examples.

It should be noted that this is changeable according to the situation. This is followed by ‘the typical behavior’ column, which attempts to describe what happened and how it could be modified, benefitting from sensitivity and reflexivity in interviewing. When these two fail, as we illustrated, then moral development (integrity) plays a role. Given this, conducting interviewing requires being sensitive and having intrapersonal and interpersonal skills, being reflexive through transparency and other techniques, and having acquired and learned research ethics. In other words, while moral development is acquiring and learning the knowledge required to conduct interviews ethically, sensitivity and reflexivity are the means and techniques to conduct interviews professionally. It is important to note that the examples provided in the following table are imagined scenarios that help clarify the interrelationship between the ‘sensitivity, reflexivity and integrity’ concepts in conducting interviews.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Our findings critically discuss the high significance of employing ‘reflexivity, sensitivity and integrity’ in conducting interviews and in transcribing and interpreting the collected data. In conducting interviews, reflexivity is useful in increasing the trustworthiness of the collected data. It also helps raise further awareness of the people engaged in the interaction.

Researchers’ reflexivity can be enhanced through eliciting prospective and retrospective reflections over time [53], writing about the personification while conducting research [54], embedding researchers’ experiences [55], allowing interaction between the interviewer, interviewees, and context [56] and using different categories of knowledge [58]. On the contrary, reflexivity can be hindered when discussing sensitive topics (e.g., intimacy) [57], or losing the focus of the researched topic [89], among others. Learning about and practicing the different types of reflexivity is important for interviewers. Methodological reflexivity [40], participant reflexivity [64], reflexive pragmatism [68], analytical reflexivity [69], contextual reflexivity [71] and emotional reflexivity are all important in the ethical and appropriate conduction of interviews. To increase the level of reflexivity, researchers need to also develop some sensitivity.

We argue that the concept of sensitivity deals with interviewers’ awareness and understanding of interviewees’ needs, interests, and preferences. Being aware and understanding is necessary for conducting interviews, in addition to the careful selection of words and showing care while discussing distressing or critical situations. In this sense, we state that sensitivity includes the features of awareness, understanding, carefulness, and care.

The application of our proposed three levels of sensitivity ‘i.e., high sensitivity during interviewing, higher sensitivity during transcribing data, and highest sensitivity and criticality during interpreting data’ are very important and should be learned and exercised by interviewers. By applying these levels of sensitivity, we believe that the ‘qualitative sensitivity’ of researchers is enhanced, leading to a strong application of ‘research integrity’. While teaching and learning research ethics differs from one context to another, it is important that teachers and learners develop a stronger awareness of ‘qualitative sensitivity’, which, if applied well, will lead to the attainment of research ethics and integrity. However, qualitative researchers need to consider not being hypersensitive, as this is not useful in interacting with other people. This demands being careful in our daily interactions, which might shape the way we interact when it comes to conducting interviews.

Finally, we contend that qualitative researchers might apply different levels of sensitivity and reflexivity in conducting and interpreting interviews. The application of a different level of sensitivity and reflexivity, the acquisition of intrapersonal and interpersonal skills, the exercise of reflexive transparency and other techniques, and the learning and teaching of research ethics are significant in conducting and interpreting interviews professionally.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and A.A.; methodology, A.A. and A.M.; software, A.A. and A.M.; validation, A.A. and A.M.; formal analysis, A.M. and A.A.; investigation, A.M. and A.A.; resources, A.A. and A.M.; data curation, A.A. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M. and A.A.; writing—review and editing, A.M. and A.A.; visualization, A.A. and A.M.; supervision, A.M. and A.A.; project administration, A.M. and A.A.; funding acquisition, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mallozzi, C.A. Voicing the interview: A researcher’s exploration on a platform of empathy. Qual. Inq. 2009, 15, 1042–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteson, S.M.; Lincoln, Y.S. Using multiple interviewers in qualitative research studies: The influence of ethic of care behaviors in research interview settings. Qual. Inq. 2009, 15, 659–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, M.; Miller-Day, M. Upward turning points and positive rapport development across time in researcher participant relationships. Qual. Res. 2007, 7, 177–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Sköldberg, K. Reflexive Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Cunliffe, A.L. Reflexive Inquiry in Organizational Research: Questions and Possibilities. Hum. Relat. 2003, 56, 983–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M. Against Reflexivity as an Academic Virtue and Source of Privileged Knowledge. Theory Cult. Soc. 2000, 17, 26–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M. Beyond Neopositivists, Romantics, and Localists: A Reflexive Approach to Interviews in Organizational Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, J.; Hepburn, A. Qualitative interviews in psychology: Problems and possibilities. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2005, 2, 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, S. A Critical Review of Qualitative Interviews in Applied Linguistics. Appl. Linguist. 2011, 32, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, D. How was it for you? The Interview Society and the irresistible rise of the (poorly analyzed) interview. Qual. Res. 2017, 17, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, C. Making interview transcripts real: The reader’s response. Work Employ. Soc. 2015, 29, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.; Kerr, R. Reflexive Conversations: Constructing Hermeneutic Designs for Qualitative Management Research. Br. J. Manag. 2015, 26, 777–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reissner, S.C. Interactional Challenges and Researcher Reflexivity: Mapping and Analysing Conversational Space. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2017, 15, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reissner, S.; Whittle, A. Interview-based research in management and organisation studies: Making sense of the plurality of methodological practices and presentational styles. Qual. Res. Organ. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 17, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection. In Qualitative Research in Health Care: Third Edition; BM: Lansing, MI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Trochim, W.M.K. The Research Methods Knowledge Base. Available online: https://conjointly.com/kb/cite-kb/ (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Castleberry, A.; Nolen, A. Themati. analysis of qualitative research data: Is it as easy as it sounds? Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018, 10, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. 30 Essential Skills for the Qualitative Researcher. SAGE Publications Ltd.:: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, H.M.; Bamberg, M.; Creswell, J.W.; Frost, D.M.; Suárez-orozco, C.; Appelbaum, M.; Cooper, H.; Kline, R.; MayoWilson, E.; Nezu, A.; et al. Reporting Standards for Qualitative Research in Psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board Task Force Report. Am. Psychol. 2018, 1, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teddlie, C.; Tashakkori, A. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences Charles; SAGE Publications, Inc: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver-Hightower, M.B. How to Write Qualitative Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Dorans, E. Reflexivity and ethical research practice while interviewing on sexual topics. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2018, 21, 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, J. “Shoot! Can We Restart the Interview?”: Lessons From Practicing “Uncomfortable Reflexivity”. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 160940692096381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambridge Dictionary. Reflexivity. In Cambridge Dictionary; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/reflexivity (accessed on 3 February 2021).

- Tomm, K. Interventive interviewing: Part III. Intending to ask lineal, circular, strategic, or reflexive questions? Fam. Process 1988, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomm, K. Interventive Interviewing: Part II. Reflexive Questioning as a Means to Enable Self-Healing. Fam. Process 1987, 26, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, A.S.G.; Harper, E.; Santos, I.S.; da Silva Gracio, M.C. Using Reflexive Interviewing to Foster Deep Understanding of Research Participants’ Perspectives. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, L. A dance between the reduction and reflexivity: Explicating the “phenomenological psychological attitude. J. Phenomenol. Psychol. 2008, 39, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipton, R. Reflexivity and the social construction of identity in interpreter-mediated asylum interviews. Translator 2008, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.; Fraser, D.; Baker, P. Reflexivity: The experience of undertaking an ethnographic study to explore issues of consent to intrapartum procedures. Evid.-Based Midwifery 2010, 8, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Garfield, S.; Reavey, P.; Kotecha, M. Footprints in a toxic landscape: Reflexivity and validation in the free association narrative interview (FANI) method. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2010, 7, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, S.; Polzer, K.; Levan, K. Space, time, and reflexive interviewing: Implications for qualitative research with active, incarcerated, and former criminal offenders. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2013, 12, 478–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.C. Radical reflexivity in cinematic adaptation: Second thoughts on reality, originality, and authority. Lit.-Film Q. 2013, 41, 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, M. Researching emotional reflexivity. Emot. Rev. 2015, 7, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, S. Contextualization, reflexivity, and the study of diabetes-related stigma. Stigmatized Vernac. 2016, 49, 153–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janzen, K.J. Into the depths of reflexivity and back again—When research mirrors personal experience: A personal journey into the spaces of liminality. Qual. Rep. 2016, 21, 1495–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, M.; Smith, J.; Majumdar, S. Insightful surgical interview training: Role of video reflexivity. Med Educ. 2017, 51, 554–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Iglesias, J. The maroon boxer briefs: Exploring erotic reflexivity in interview research. Qual. Res. 2020, 21, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, D. On becoming a qualitative researcher: The value of reflexivity. Qual. Rep. 2007, 12, 82–101. Available online: http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR12-1/watt.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Palaganas, E.C.; Sanchez, M.C.; Molintas, M.V.P.; Caricativo, R.D. Reflexivity in qualitative research: A journey of learning. Qual. Rep. 2017, 22, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, V. The research interview: Reflective practice and reflexivity in research processes. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2018, 41, 237–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, A.; Oldfield, J.; Ortiz, E. Image and word on the street: A reflexive, phased approach to combining participatory visual methods and qualitative interviews to explore resilience with street-connected young people in Guatemala City. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2019, 19, 176–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, S.; Stevenson, J. The interview reconsidered: Context, genre, reflexivity and interpretation in sociological approaches to interviews in higher education research. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2013, 32, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duemer, L. “Don’t Say Merry Christmas to Aunt Kay”: The reflexive nature of biographical research. Vitae Scholast. 2019, 36, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Slembrouck, S. Reflexivity and the research interview. In Crit. Discourse Stud. 2004, 1, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckner, S. Taking the debate on reflexivity further. J. Soc. Work. Pract. 2005, 19, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J. Reflexivity: Interviewing women and men formerly addicted to drugs and/or alcohol. Qual. Rep. 2014, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denizen, N.K. The reflexive interview and a performative social science. Qual. Res. 2001, 1, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, J. Why we interview now-Reflexivity and perspective in a longitudinal study. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. Theory Pract. 2003, 6, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, M.L. Bodies that speak: Examining the dialogues in research interactions. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Busso, L. III. Embodying feminist politics in the research interview: Material bodies and reflexivity. Fem. Psychol. 2007, 17, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertkan-Özünlü, S. Reflexive accounts about qualitative interviewing within the context of educational policy in North Cyprus. Qual. Res. 2007, 7, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walby, K. Interviews as encounters: Issues of sexuality and reflexivity when men interview men about commercial same sex relations. Qual. Res. 2010, 10, 639–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, T.; Kumar, K.; Serrant-Green, L. “Would you decide to keep the power?”: Reflexivity on the interviewer-interpreter-interviewee triad in interviews with female Punjabi rheumatoid arthritis patients. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2013, 12, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jootun, D.; McGhee, G.; Marland, G.R. Reflexivity: Promoting rigour in qualitative research. Nurs. Stand. 2009, 23, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezalla, A.E.; Pettigrew, J.; Miller-Day, M. Researching the researcher-as-instrument: An exercise in interviewer self-reflexivity. Qual. Res. 2012, 12, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, A. Reflexivity: Unmarried Japanese male interviewing married Japanese women about international marriage. Qual. Res. 2013, 13, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipp, A. Developing the reflexive dimension of reflection: A framework for debate. Int. J. Mult. Res. Approaches 2007, 1, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, M. Interviewing fathers and sons together: Exploring the potential of joint interviews for research on family farms. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 36, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.H. Participant Reflexivity in Community-Based Participatory Research: Insights from Reflexive Interview, Dialogical Narrative Analysis, and Video Ethnography. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 25, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riach, K. Exploring participant-centred reflexivity in the research interview. Sociology 2009, 43, 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, A.K.; Kanak Zwier, R.; Tracy, S.J. Dialogic Interviewing and Flickers of Transformation: An Examination and Delineation of Interactional Strategies That Promote Participant Self-Reflexivity. Qual. Inq. 2015, 21, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.; Dagg, J. Using reflexive lifelines in biographical interviews to aid the collection, visualization and analysis of resilience. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2019, 14, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearity, B.T. A reflexive pragmatist reading of Alvesson’s interpreting interviews. Qual. Rep. 2011, 16, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collyer, F. Reflexivity and the sociology of science and technology: The invention of “Eryc” the antibiotic. Qual. Rep. 2011, 16, 316–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, D.M.; Pilnick, A.; Hall, A.; Collins, L. Participants’ use of enacted scenes in research interviews: A method for reflexive analysis in health and social care. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 151, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flogen, S. The challenges of reflexivity. Qual. Rep. 2011, 16, 905–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J. Using Psychoanalysis in Qualitative Research: Countertransference-Informed Researcher Reflexivity and Defence Mechanisms in Two Interviews about Migration. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2013, 10, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, W.C. Sensitivity. In Encyclopedia of Research Design; Salkind, N.J., Ed.; Sage publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 1338–1339. [Google Scholar]

- Low, J. Researcher sensitivity. In The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; Given, L.M., Ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; p. 780. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, J.; Merenski, J.P. Recognition-Based Measures of Ethical Sensitivity and Reformulated Cognitive Moral Development: An Examination and Evidence of Nomological Validity. Teach. Bus. Ethics 2000, 4, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, L.A. Moral development in a global world: Research from a cultural-developmental perspective. In Moral Development in a Global World: Research from a Cultural-Developmental Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Vicent, M. La ética del cuidado y Carol Gilligan: Una crítica a la teoría del desarrollo moral de Kohlberg para la definición de un nivel moral postconvencional contextualista [The Ethics of Care and Carol Gilligan: A Critique of Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development for the Definition of a Postconventional Contextualist Moral Level]. Daimon 2016, 0507, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, J.A.; Green, P.J. Playing the PhD Game with Integrity: Connecting Research, Professional Practice and Educational Context; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hren, D.; Vujaklija, A.; Ivanišević, R.; Knežević, J.; Marušić, M.; Marušić, A. Students’ moral reasoning, Machiavellianism and socially desirable responding: Implications for teaching ethics and research integrity. Med. Educ. 2006, 40, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semerci, Ç. The opinions of medicine faculty students regarding cheating in relation to Kohlberg’s moral development concept. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2006, 34, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthanna, A. Plagiarism: A Shared Responsibility of All, Current Situation, and Future Actions in Yemen. Account. Res. 2016, 23, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenherr, J.R. Social-cognitive barriers to ethical authorship. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, J.M.; Anderson, E.E.; Chibnall, J.; Carroll, K.; Gibb, T.; Ogbuka, C.; Rubbelke, T. Understanding research misconduct: A comparative analysis of 120 cases of professional wrongdoing. Account. Res. 2013, 20, 320–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wester, K.; Willse, J.; Davis, M. Psychological climate, stress, and research integrity among research counselor educators: A preliminary study. Couns. Educ. Superv. 2010, 50, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wester, K.L. Teaching research integrity in the field of counseling. Couns. Educ. Superv. 2007, 46, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, T.N. Using creative writing techniques to enhance the case study method in research integrity and ethics courses. J. Acad. Ethics 2008, 6, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, C.L.; Schwartz, A.M.; Coyle, M.A.; Goldberg, M.H. A classroom activity for teaching Kohlberg’s theory of moral development. Teach. Psychol. 2019, 46, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satalkar, P.; Shaw, D. How do researchers acquire and develop notions of research integrity? A qualitative study among biomedical researchers in Switzerland. BMC Med. Ethics 2019, 20, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, L.; Gough, B. Reflexivity: A Practical Guide for Researchers in Health and Social Sciences. In Reflexivity: A Practical Guide for Researchers in Health and Social Sciences; Wiley-Blackwell: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 1–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).