Are You Dominated by Your Affects? How and When Do Employees’ Daily Affective States Impact Learning from Project Failure?

Abstract

1. Introduction

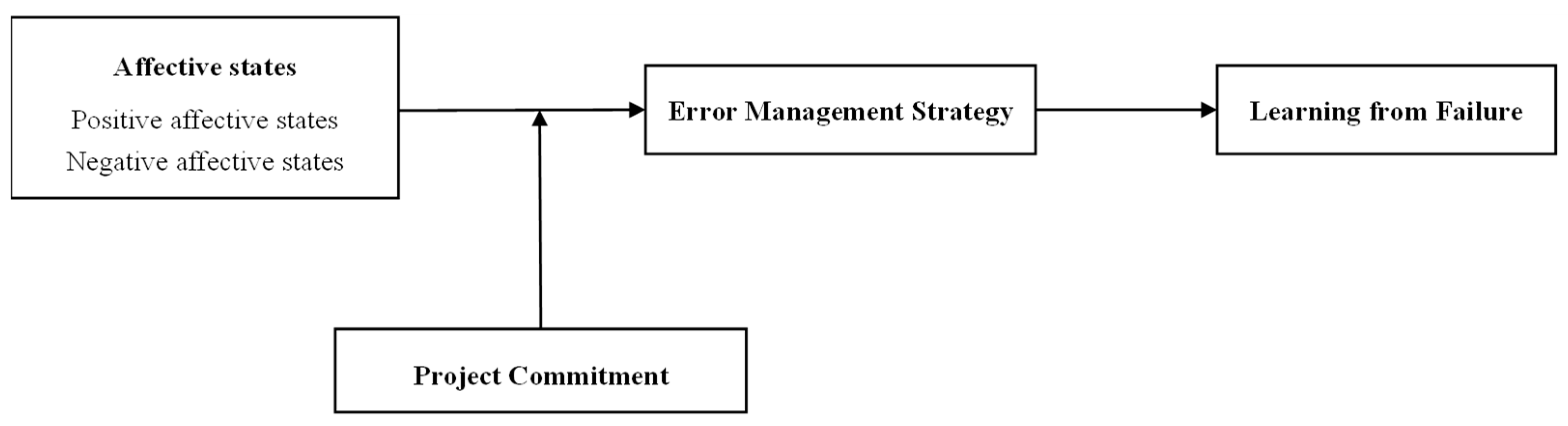

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Affective States in Organizational Research

2.2. Positive Affective States and Error Management Strategy

2.3. Negative Affective States and Error Management Strategy

2.4. Error Management Strategy and Learning from Failure

2.5. Error Management Strategy, Project Commitment, and Learning from Failure

3. Research Design

3.1. Participants and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement

3.2.1. Positive and Negative Affective States

3.2.2. Error Management Strategy (EMS)

3.2.3. Project Commitment

3.2.4. Learning from Failure

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.4. Testing Validity

4. Hypothesis Testing

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Coefficient Test

4.2. Testing Mediating Effects

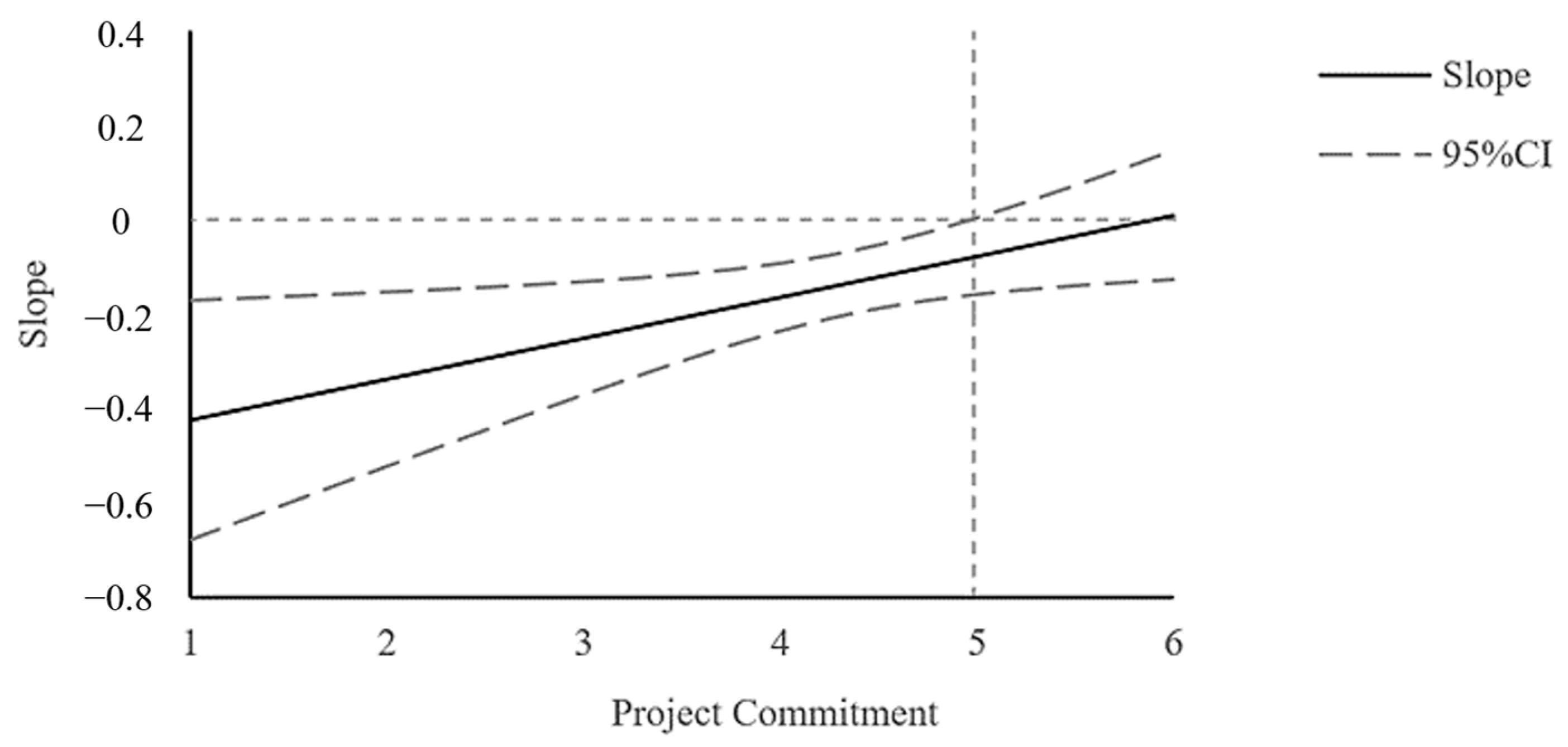

4.3. Testing Moderating Effects

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Items | Standardized Factor Loadings | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive affective states | PA1 | 0.78 | 0.88 | 0.50 |

| PA2 | 0.74 | |||

| PA3 | 0.70 | |||

| PA4 | 0.66 | |||

| PA5 | 0.74 | |||

| PA6 | 0.60 | |||

| PA7 | 0.73 | |||

| Negative affective states | NA1 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.51 |

| NA2 | 0.78 | |||

| NA3 | 0.62 | |||

| NA4 | 0.89 | |||

| NA5 | 0.75 | |||

| NA6 | 0.64 | |||

| NA7 | 0.54 | |||

| Error management strategy | EMS1 | 0.84 | 0.94 | 0.50 |

| EMS2 | 0.62 | |||

| EMS3 | 0.68 | |||

| EMS4 | 0.69 | |||

| EMS5 | 0.70 | |||

| EMS6 | 0.72 | |||

| EMS7 | 0.52 | |||

| EMS8 | 0.74 | |||

| EMS9 | 0.64 | |||

| EMS10 | 0.74 | |||

| EMS11 | 0.82 | |||

| EMS12 | 0.54 | |||

| EMS13 | 0.70 | |||

| EMS14 | 0.62 | |||

| EMS15 | 0.78 | |||

| EMS16 | 0.74 | |||

| EMS17 | 0.83 | |||

| Error aversion strategy | EAS1 | 0.65 | 0.92 | 0.51 |

| EAS2 | 0.73 | |||

| EAS3 | 0.78 | |||

| EAS4 | 0.57 | |||

| EAS5 | 0.73 | |||

| EAS6 | 0.62 | |||

| EAS7 | 0.72 | |||

| EAS8 | 0.59 | |||

| EAS9 | 0.86 | |||

| EAS10 | 0.63 | |||

| EAS11 | 0.88 | |||

| Project commitment | PC1 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0.56 |

| PC2 | 0.67 | |||

| PC3 | 0.75 | |||

| PC4 | 0.71 | |||

| PC5 | 0.83 | |||

| Learning from failure | LFF1 | 0.70 | 0.91 | 0.57 |

| LFF2 | 0.57 | |||

| LFF3 | 0.69 | |||

| LFF4 | 0.80 | |||

| LFF5 | 0.84 | |||

| LFF6 | 0.84 | |||

| LFF7 | 0.83 | |||

| LFF8 | 0.71 |

| Participating Companies | Non-Participating Companies | t | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 58 | N = 342 | |||||

| Means | SE | Means | SE | |||

| Industries | 3.09 | 1.45 | 3.02 | 1.42 | 0.34 | 0.74 |

| Years of establishment | 18.53 | 6.94 | 19.3 | 5.56 | −0.94 | 0.35 |

| Type of companies | 5.48 | 1.41 | 5.09 | 1.76 | 1.88 | 0.06 |

Appendix B. Scales Items Used in Study

- (1)

- For me, errors are very useful for improving the work process.

- (2)

- After an error has occurred, I will analyze it thoroughly.

- (3)

- After an error, I think through how to correct it.

- (4)

- I think a lot about how an error could have been avoided.

- (5)

- If something went wrong, I take the time to think it through.

- (6)

- After making a mistake, I try to analyze what caused it.

- (7)

- My errors point me at what I can improve.

- (8)

- An error provides important information for the continuation of the work.

- (9)

- When an error is made, it is corrected right away.

- (10)

- When mastering a task, I can learn a lot from the mistakes.

- (11)

- When an error has occurred, I usually know how to rectify it.

- (12)

- Although I make mistakes, I don’t let go of the final goal.

- (13)

- When I am unable to correct an error by myself, I turn to my colleagues.

- (14)

- If I am unable to continue my work after an error, I can rely on my colleagues.

- (15)

- When I make an error, I can ask my colleagues for advice on how to continue.

- (16)

- When I make an error, I share it with my colleagues so that they don’t make the same mistake.

- (1)

- I feel stressed when making mistakes.

- (2)

- I am often afraid of making errors.

- (3)

- In general, I feel embarrassed after making a mistake.

- (4)

- I get upset and irritated if an error occurs.

- (5)

- There is no point in discussing errors with my colleagues.

- (6)

- During my work, I am often concerned that errors might occur.

- (7)

- When I make a mistake in the work, the best way is to cover up my mistakes.

- (8)

- I prefer to keep errors to myself.

- (9)

- Employees who admit their errors are asking for trouble.

- (10)

- It can be harmful to make my errors known to others.

- (11)

- I agree with that “Why admit an error when no one will find out”?

- (1)

- I feel fully responsible for achieving the common project goals.

- (2)

- I am proud to be part of the project.

- (3)

- I value this project a lot.

- (4)

- This project has the strong commitment of me.

- (5)

- I committed not only to my teams, but to the overall project.

- (1)

- I am more willing to help others deal with their failures.

- (2)

- I am more tolerant of others’ shortcomings when it comes to projects.

- (3)

- I am a more forgiving person at work.

- (4)

- I have learned to better execute a project’s strategy.

- (5)

- I can more effectively run a new project.

- (6)

- I have improved my ability to make important contributions to a project.

- (7)

- I can “see” earlier the signs that a project is in trouble.

- (8)

- I now realize the mistakes that we made that led to the project’s failure.

References

- Bartik, A.W.; Bertrand, M.; Cullen, Z.; Glaeser, E.L.; Luca, M.; Stanton, C. The impact of COVID-19 on small business outcomes and expectations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 17656–17666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimas, P.; Czakon, W.; Kraus, S.; Kailer, N.; Maalaoui, A. Entrepreneurial Failure: A Synthesis and Conceptual Framework of its Effects. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2020, 18, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucbasaran, D.; Westhead, P.; Wright, M.; Flores, M. The nature of entrepreneurial experience, business failure and comparative optimism. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucbasaran, D.; Shepherd, D.A.; Lockett, A.; Lyon, S.J. Life after business failure: The process and consequences of business failure for entrepreneurs. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 163–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, G.H.; Gilligan, S.G.; Monteiro, K.P. Selectivity of learning caused by affective states. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1981, 110, 451–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falout, J.; Elwood, J.; Hood, M. Demotivation: Affective states and learning outcomes. System 2009, 37, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. Emotions and Learning; International Academy of Education (IAE): Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R.; Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. Academic emotions and student engagement. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 259–282. [Google Scholar]

- D’mello, S.; Graesser, A. Dynamics of affective states during complex learning. Learn. Instr. 2012, 22, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Mourik, O.; Grohnert, T.; Gold, A. Mitigating work conditions that can inhibit learning from errors: Benefits of error management climate perceptions. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1033470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dyck, C.; Frese, M.; Baer, M.; Sonnentag, S. Organizational Error Management Culture and Its Impact on Performance: A Two-Study Replication. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1228–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, M. Error Management in Training: Conceptual and Empirical Results. In Organizational Learning and Technological Change; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995; pp. 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guchait, P.; Kim, M.G.; Namasivayam, K. Error management at different organizational levels–frontline, manager, and company. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Pearson Education, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- MacGill, V. Reframing Cognitive Behaviour Theory from a Systems Perspective. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2017, 31, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenhausen, G.V.; Moreno, K.N. How do I feel about them? The role of affective reactions in intergroup perception. In The Message Within: The Role of Subjective Experience in Social Cognition and Behavior; Psychology Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K.J.; Waugh, C.E.; Fredrickson, B.L. Smile to see the forest: Facially expressed positive emotions broaden cognition. Cognit. Emot. 2010, 24, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A.; Latham, G.P. A Theory of Goal Setting & Task Performance; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hoegl, M.; Weinkauf, K.; Gemuenden, H.G. Interteam Coordination, Project Commitment, and Teamwork in Multiteam R&D Projects: A Longitudinal Study. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nummenmaa, L.; Saarimäki, H. Emotions as discrete patterns of systemic activity. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 693, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraiger, K.; Billings, R.S.; Isen, A.M. The influence of positive affective states on task perceptions and satisfaction. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1989, 44, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoler, A.L. Affective states. In A Companion to the Anthropology of Politics; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 4–20. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A. The independence of positive and negative affect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 47, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosschot, J.F.; Thayer, J.F. Heart rate response is longer after negative emotions than after positive emotions. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2003, 50, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Barsade, S.G.; Mueller, J.S.; Staw, B.M. Affect and creativity at work. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 367–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugade, M.M.; Fredrickson, B.L. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, A.; Tremmel, S.; Sonnentag, S. The power of affect: A three-wave panel study on reciprocal relationships between work events and affect at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 92, 436–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakshan, N.; Smyth, S.; Eysenck, M.W. Effects of state anxiety on performance using a task-switching paradigm: An investigation of attentional control theory. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2009, 16, 1112–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Branigan, C. Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cogn. Emot. 2005, 19, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Shafran, R.; Cooper, Z. A cognitive behavioural theory of anorexia nervosa. Behav. Res. Ther. 1999, 37, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buvik, M.P.; Tvedt, S.D. The Influence of Project Commitment and Team Commitment on the Relationship between Trust and Knowledge Sharing in Project Teams. Proj. Manag. J. 2017, 48, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, B.; Yang, K.; Yang, C.; Yuan, W.; Song, S. When Project Commitment Leads to Learning from Failure: The Roles of Perceived Shame and Personal Control. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.S.; Beehr, T.A. Working with the stress of errors: Error management strategies as coping. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2017, 24, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-H.; Liu, G.H.W.; Lee, N.C.-A. Effects of Passive Leadership in the Digital Age. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 701047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmreich, R.L.; Merritt, A.C. Safety and error management: The role of crew resource management. In Aviation Resource Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Patzelt, H.; Wolfe, M. Moving forward from project failure: Negative emotions, affective commitment, and learning from the experience. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 1229–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzelt, H.; Gartzia, L.; Wolfe, M.T.; Shepherd, D.A. Managing negative emotions from entrepreneurial project failure: When and how does supportive leadership help employees? J. Bus. Ventur. 2021, 36, 106129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, S.E. The emotional impact of tragic loss: Six tactics to find that silver lining. Ind. Saf. Hyg. News 2008, 42, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Meijman, T.F.; Mulder, G. Psychological aspects of workload. In Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology—Work Psychology; Drenth, P.J.D., Thierry, H., De Wolff, C.J., Eds.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 1998; Volume 2, pp. 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Covin, J.G.; Kuratko, D.F. Project failure from corporate entrepreneurship: Managing the grief process. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguzzoli, R.; Lengler, J.; Sousa, C.M.P.; Benito, G.R.G. Here We Go Again: A Case Study on Re-entering a Foreign Market. Br. J. Manag. 2020, 32, 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremmel, S.; Sonnentag, S.; Casper, A. How was work today? Interpersonal work experiences, work-related conversations during after-work hours, and daily affect. Work. Stress 2018, 33, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Benítez, R.; Coll-Martín, T.; Carretero-Dios, H.; Lupiáñez, J.; Acosta, A. Trait cheerfulness sensitivity to positive and negative affective states. Humor 2020, 33, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, J.; Hobbs, A. Managing Maintenance Error: A Practical Guide; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Frese, M.; Keith, N. Action errors, error management, and learning in organizations. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015, 66, 661–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhaiem, K.; Halilem, N. The worst is not to fail, but to fail to learn from failure: A multi-method empirical validation of learning from innovation failure. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 190, 122427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusin, J.; Belghit, A.G. Error reframing: Studying the promotion of an error management culture. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Rodrigues, S.; Santos, E.; Miguel, I. Relationship marketing through error management and organisational performance: Does it matter? In Transforming Relationship Marketing; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, H.; Richter, A.W.; Semrau, T. Employee Learning from Failure: A Team-as-Resource Perspective. Organ. Sci. 2019, 30, 694–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Javed, U.; Shoukat, A.; Bashir, N.A. Does meaningful work reduce cyberloafing? Important roles of affective commitment and leader-member exchange. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2019, 40, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzieva, M.; Morabito, V. Learning from experience: The project team is the key. Bus. Syst. Res. Int. J. Soc. Adv. Innov. Res. Econ. 2016, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, R.R.; Wright, P.M. The impact of high-performance human resource practices on employees’ attitudes and behaviors. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 366–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Song, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Huang, L.; Chen, X. Shame on You! When and Why Failure-Induced Shame Impedes Employees’ Learning from Failure in the Chinese Context. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 725277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvenpaa, S.L.; Staples, D.S. Exploring Perceptions of Organizational Ownership of Information and Expertise. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 151–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology: Methodology; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, E. Development and Validation of an Internationally Reliable Short-Form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2007, 38, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackinnon, A.; Jorm, A.F.; Christensen, H.; Korten, A.; Jacomb, P.A.; Rodgers, B. A short form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule: Evaluation of factorial validity and invariance across demographic variables in a community sample. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1999, 27, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, M.D.; Edmondson, A.C. Confronting failure: Antecedents and consequences of shared beliefs about failure in organizational work groups. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2001, 22, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, X.; Ning, G.; Wang, Y.; Song, S. The relationship between anger and learning from failure: The moderating effect of resilience and project commitment. Curr. Psychol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stichter, M. Learning from Failure: Shame and Emotion Regulation in Virtue as Skill. Ethical Theory Moral Pract. 2020, 23, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guchait, P.; Qin, Y.; Madera, J.; Hua, N.; Wang, X. Impact of error management culture on organizational performance, management-team performance and creativity in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2018, 21, 335–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S.; Frese, M.; Mertins, J.C.; Hardt-Gawron, J.V. The role of error management culture for firm and individual innovativeness. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2018, 67, 428–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Lu, Y.; Wang, X.; Pang, L. Challenge stressors and learning from failure: The moderating roles of emotional intelligence and error management culture. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, D.A.; White, M.; York-Crowe, E.; Stewart, T.M. Cognitive-Behavioral Theories of Eating Disorders. Behav. Modif. 2004, 28, 711–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollon, S.D.; Beck, A.T. Cognitive and cognitive-behavioral therapies. In Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt, K.; Miller, J.S.; Freeman, S.J.; Hom, P.W. Examining Project Commitment in Cross-Functional Teams: Antecedents and Relationship with Team Performance. J. Bus. Psychol. 2013, 29, 443–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, M.D.; Tsitouri, E. Positive psychology in the working environment. Job demands-resources theory, work engagement and burnout: A systematic literature review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1022102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Models | CMIN | DF | CMIN/DF | IFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Six-factor model (PA, NA, EMS, EAS, PC, LFF) | 3144.86 | 1391 | 2.26 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.04 |

| Five-factor model 1 (PA + NA, EMS, EAS, PC, LFF) | 4101.66 | 1396 | 2.94 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.05 |

| Five-factor model 2 (PA, NA, EMS + EAS, PC, LFF) | 4972.57 | 1396 | 3.56 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.06 |

| Four-factor model (PA + NA, EMS + EAS, PC, LFF) | 5930.65 | 1400 | 4.24 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.07 |

| Three-factor model (PA + NA + PC, EMS + EAS, LFF) | 7233.90 | 1403 | 5.16 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.07 |

| Two-factor model (PA + NA + PC, EMS + EAS + LFF) | 8608.21 | 1405 | 6.13 | 0.63 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.08 |

| One-factor model (PA + NA + PC + EMS + EAS + LFF) | 9356.29 | 1406 | 6.66 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.09 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Positive affective states | |||||

| 2 Negative affective states | 0.38 | ||||

| 3 Error management strategy | 0.38 | 0.24 | |||

| 4 Error aversion strategy | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.33 | ||

| 5 Project commitment | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.50 | 0.25 | |

| 6 Learning from failure | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.48 | 0.25 | 0.74 |

| Means | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Gender | 0.77 | 0.42 | |||||||||||

| 2 Age | 31.65 | 5.50 | 0.04 | ||||||||||

| 3 Education Level | 4.36 | 0.68 | 0.00 | 0.19 ** | |||||||||

| 4 Work Tenure | 1.76 | 0.73 | 0.01 | 0.69 ** | 0.19 ** | ||||||||

| 5 Understanding of the Reasons of Failure | 2.93 | 0.96 | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.10 ** | −0.08 * | (0.870) | ||||||

| 6 Positive Affective States | 3.58 | 0.57 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.05 | −0.02 | 0.01 | (0.796) | |||||

| 7 Negative Affective States | 2.09 | 0.53 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.12 ** | 0.06 | −0.17 ** | (0.782) | ||||

| 8 Error Management Strategy | 4.70 | 0.53 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.28 ** | −0.19 ** | (0.885) | |||

| 9 Error Aversion Strategy | 2.97 | 0.77 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.06 | −0.22 ** | 0.26 ** | −0.14 ** | (0.852) | ||

| 10 Project Commitment | 4.44 | 0.86 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.07 * | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.23 ** | −0.09 * | 0.39 ** | −0.17 ** | (0.863) | |

| 11 Learning from Failure | 4.58 | 0.84 | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.07 * | 0.19 ** | −0.16 ** | 0.42 ** | −0.18 ** | 0.48 ** | (0.909) |

| Variables | Error Management Strategy | Learning from Failure | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1.1 | Model 1.2 | Model 1.3 | Model 1.4 | Model 2.1 | Model 2.2 | Model 2.3 | |

| 1 Gender | −0.06 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.13 | −0.10 | −0.10 |

| 2 Age | 0.18 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.10 | −0.04 | −0.04 |

| 3 Education Level | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.13 ** | 0.13 ** | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.08 |

| 4 Work Tenure | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.02 |

| 5 Understanding of the Reasons of Failure | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.08 * | −0.07 * | −0.06 |

| 6 Positive Affective States | 0.26 *** | 0.18 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.05 | ||

| 7 Negative Affective States | −0.15 *** | −0.13 *** | −0.13 *** | −0.12 ** | −0.04 | ||

| 8 Project Commitment | 0.34 *** | 0.35 *** | |||||

| 9 Project Commitment × Positive Affective States | −0.02 | ||||||

| 10 Project Commitment × Negative Affective States | 0.07 * | ||||||

| 11 Error Management Strategy | 0.38 *** | ||||||

| 12 Error Aversion Strategy | −0.11 ** | ||||||

| R2 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.19 |

| △R2 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.14 | ||

| F | 0.62 | 12.56 | 25.79 | 21.32 | 1.79 | 7.04 | 21.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, W.; Li, L.; Song, S.; Jiang, W. Are You Dominated by Your Affects? How and When Do Employees’ Daily Affective States Impact Learning from Project Failure? Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13060514

Wang W, Li L, Song S, Jiang W. Are You Dominated by Your Affects? How and When Do Employees’ Daily Affective States Impact Learning from Project Failure? Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(6):514. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13060514

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Wenzhou, Longdi Li, Shanghao Song, and Wendi Jiang. 2023. "Are You Dominated by Your Affects? How and When Do Employees’ Daily Affective States Impact Learning from Project Failure?" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 6: 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13060514

APA StyleWang, W., Li, L., Song, S., & Jiang, W. (2023). Are You Dominated by Your Affects? How and When Do Employees’ Daily Affective States Impact Learning from Project Failure? Behavioral Sciences, 13(6), 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13060514