Modeling and Quantifying the Impact of Personified Communication on Purchase Behavior in Social Commerce

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Social Commerce

2.2. Personified Communication

2.3. Technology Adoption Model (TAM) and Beyond

3. Research Method

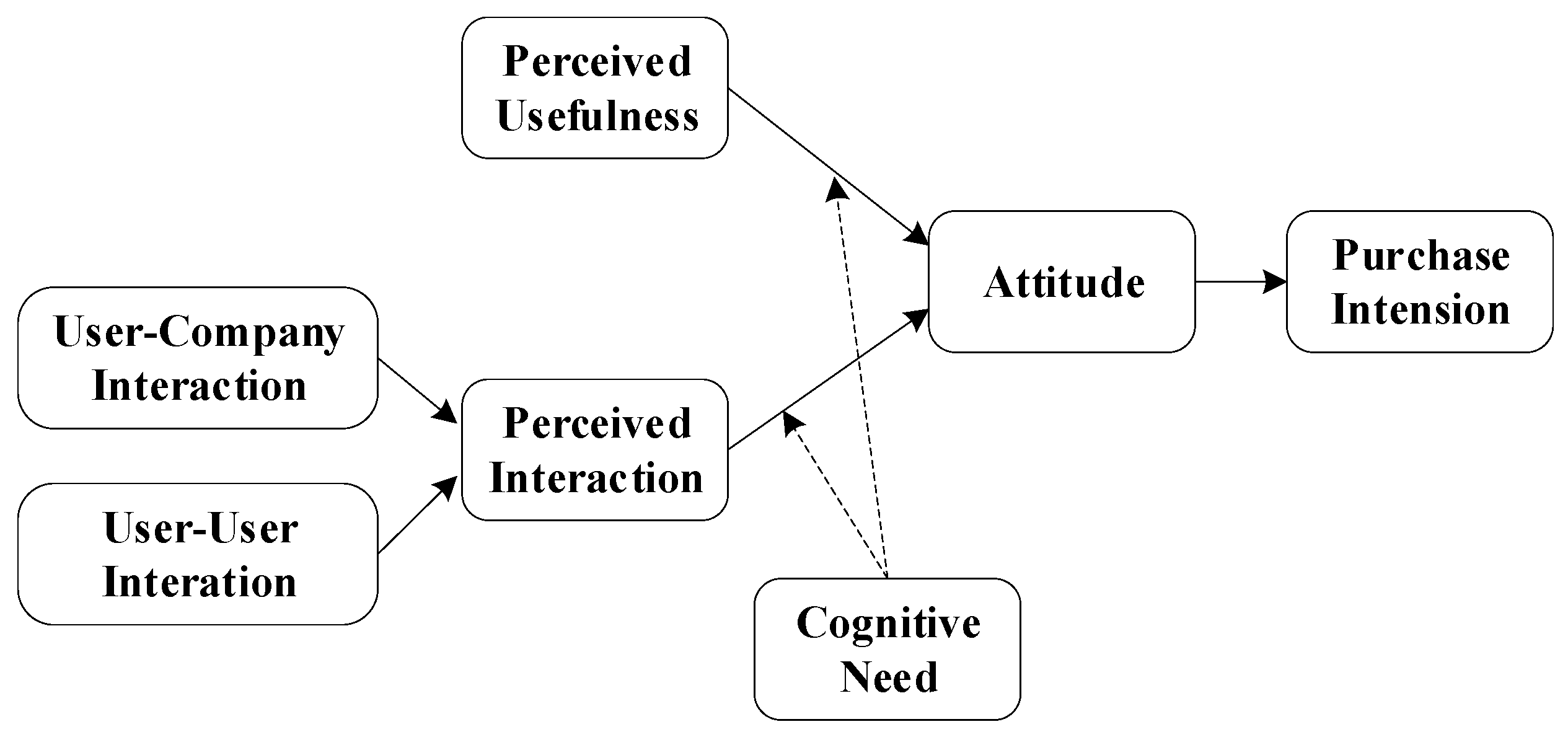

3.1. Hypothesis

3.1.1. Hypothesis on the Influence of Consumers’ Attitude on Purchase Intention

3.1.2. Hypothesis on the Influencing Factors of Consumers’ Attitude

3.1.3. Hypothesis of Consumers’ Cognitive Need

3.2. Research Model

4. Empirical Study and Results

4.1. Questionnaire Design

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Model Validation

- (1)

- Reliability. We use SPSS 22.0 to analyze reliability. The specific results were KMO = 0.874. The Bartlett sphericity test results were significant (SIG = 0.000). The Cronbach’s α coefficient and combination reliability of the structural variables were greater than 0.8, indicating the scale’s high reliability. The detailed results are shown in Table 2;

- (2)

- Convergence validity. The standardized factor loads of the significant variables of the model were higher than 0.8 and reached a considerable level. The model’s component reliability was more significant than 0.7. The average variance extraction rate was more significant than 0.5;

- (3)

- Discriminant validity. As shown in Table 3, each variable’s correlation coefficient is less than the square root of the average variance extraction rate of the corresponding variable, so we can know that it has good discriminant validity.

4.4. SEM Analysis

4.5. Mediating Effect Test

4.6. Moderated Mediation Analysis

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Research Conclusions

5.2. Suggestions

5.2.1. E-Commerce Providers Are Suggested to Offer High-Quality Service Information through Social Media

5.2.2. E-Commerce Companies Must Communicate Better with Consumers through Social Media

5.2.3. E-Commerce Providers Are Encouraged to Promote Consumer Interaction on Social Networks

5.2.4. E-Commerce Companies Are Suggested to Create Topics in Social Media and Offer Rewards to Interactive Users

5.3. Limitations and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hajli, N. Social Commerce and the Future of E-commerce. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 108, 106133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajli, N.; Sims, J. Social Commerce: The Transfer of Power from Sellers to Buyers. Technol. Forecast. Social Chang. 2015, 94 (Suppl. C), 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, X.; Wang, X.; Hajli, N. Building E-Commerce Satisfaction and Boosting Sales: The Role of Social Commerce Trust and Its Antecedents. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2019, 23, 328–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazi, S.; Haddad, H.; Al-Amad, A.; Rees, D.; Hajli, N. Investigating the Impact of Situational Influences and Social Support on Social Commerce during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Tang, G.; Li, X.; Ren, A. The Effects of Appearance Personification of Service Robots on Customer Decision-Making in the Product Recommendation Context. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2023, 123, 578–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajli, N. The Impact of Positive Valence and Negative Valence on Social Commerce Purchase Intention. Inf. Technol. People 2020, 33, 774–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, F. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.; Gordon, B.; Davis, F. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, R.; Mishra, R. A Review of Evaluation of Theories and Models of Technology Adoption. Indore Manag. J. 2014, 6, 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, M. Users of the World, Unite! The Challenges and Opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Chikandiwa, S.; Contogiannis, E.; Jembere, E. The Adoption of Social Media Marketing in South African Banks. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2013, 25, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jung, W.; Yang, S.; Kim, H. Design of Sweepstakes-Based Social Media Marketing for Online Customer Engagement. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 20, 119–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietzmann, J.; Hermkens, K.; Mccarthy, I. Social Media? Get Serious! Understanding the Functional Building Blocks of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2011, 54, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohammadian, M.; Mohammadreza, M. Identify the Success Factors of Social Media. Int. Bus. Manag. 2012, 4, 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wawrowski, B.; Otola, I. Social Media Marketing in Creative Industries: How to Use Social Media Marketing to Promote Computer Games? Information 2020, 11, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Huang, L.; Roth, M. The Influence of Social Media Interactions on Consumer–Brand Relationships: A Three-Country Study of Brand Perceptions and Marketing Behaviors. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2016, 33, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J. Dimensions of Brand Personality. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, J.; Kaate, I.; Kamel, A.; Jung, S.; Jansen, B. How Does Personification Impact Ad Performance and Empathy? An Experiment with Online Advertising. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2021, 37, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobile, T.; Kalbaska, N. An Exploration of Personalization in Digital Communication. Insights in Fashion. In Proceedings of the 22nd HCI International Conference (HCI), Copenhagen, Denmark, 19–24 July 2020; pp. 456–473. [Google Scholar]

- Puzakova, M.; Kwak, H.; Rocereto, J. When Humanizing Brands Goes Wrong: The Detrimental Effect of Brand Anthropomorphization Amid Product Wrongdoings. J. Mark. 2013, 77, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Zhu, C.; Peng, Z.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y. User Willingness toward Knowledge Sharing in Social Networks. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marakarkandy, B.; Yajnik, N.; Dasgupta, C. Enabling Internet Banking Adoption: An Empirical Examination with an Augmented Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2017, 30, 263–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Fang, S.; Jin, P. Modeling and Quantifying User Acceptance of Personalized Business Modes Based on TAM, Trust and Attitude. Sustainability 2018, 10, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shachak, A.; Kuziemsky, C.; Petersen, C. Beyond TAM and UTAUT: Future Directions for HIT Implementation Research. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 100, 103315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammenwerth, E. Technology Acceptance Models in Health Informatics: TAM and UTAUT. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2019, 263, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jou, Y.; Shiang, W.; Silitonga, R.; Adilah, M.; Halim, A. Assessing Factors That Influence Womenpreneurs’ Intention to Use Technology: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, S.; Siegal, W. Informational Influence in Organizations: An Integrated Approach to Knowledge Adoption. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.; Xu, X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y. Trust, Psychological Need, and Motivation to Produce User-Generated Content: A Self-Determination Perspective. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2014, 15, 241. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, T. The Effect of Complex Visual Experiences and User Interaction on Attitudes and Intentions in Luxury Purchase. In Proceedings of the BDIOT, Melbourne, Australia, 22–24 August 2019; pp. 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, J.; Petty, R. The Need for Cognition. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 42, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Briñol, P.; Horcajo, J. The Effect of Need for Cognition on the Stability of Prejudiced Attitudes toward South American Immigrants. Psicothema 2013, 25, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, H.; Paruthi, M.; Islam, J.; Hollebeek, L. The Role of Brand Community Identification and Reward on Consumer Brand Engagement and Brand Loyalty in Virtual Brand Communities. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 46, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preece, J. Sociability and usability in online communities: Determining and Measuring success. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2001, 20, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, F. The Interaction Effects of Online Reviews and Free Samples on Consumers’ Downloads: An Empirical Analysis. Inf. Process. Manag. 2019, 56, 102071. [Google Scholar]

- Macinnis, D.; Moorman, C.; Jaworski, B. Enhancing and Measuring Consumers’ Motivation, opportunity, and ability to process brand information from ads. J. Mark. 1991, 55, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yeh, H.; Chang, T. Mining Customer Shopping Behavior: A Method Encoding Customer Purchase Decision Attitude. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Serv. Sect. 2018, 10, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.; Scharkow, M. The Relative Trustworthiness of Inferential Tests of the Indirect Effect in Statistical Mediation Analysis: Does Method Really Matter? Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milin, P.; Hadzic, O. Moderating and Mediating Variables in Psychological Research. In International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 849–852. [Google Scholar]

- Hajli, N. Social Commerce Constructs and Consumer’s Intention to Buy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajli, N.; Wang, Y.; Tajvidi, M.; Hajli, M. People, Technologies, and Organizations Interactions in a Social Commerce Era. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2017, 64, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tajvidi, M.; Wang, Y.; Hajli, N.; Love, P. Brand Value Co-Creation in Social Commerce: The Role of Interactivity, Social Support, and Relationship Quality. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 115, 105238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jin, E.; Oh, J. The Role of Emotion in Interactivity Effects: Positive Emotion Enhances Attitudes, Negative Emotion Helps Information Processing. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2022, 41, 3487–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Item | Questionnaire Question |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | PU1 | Reading about the personification of brand enterprises on Weibo has provided me with an opportunity to purchase my desired products. |

| PU2 | Reading about the personification of brand enterprises on Weibo has helped me to understand their products or services better. | |

| PU3 | Reading about the personification of brand enterprises on Weibo has improved my shopping efficiency. | |

| Perceived Interaction (PIU) (User-User) | PIU1 | Through personified communication with enterprises, I have been able to increase the frequency of my interactions with other consumers. |

| PIU2 | Through personification communication with enterprises, I feel that my connections with other consumers have been strengthened. | |

| PIU3 | As a consumer, I often engage in communication and interactions on the personified Weibo accounts of enterprises. | |

| Perceived Interaction (PIC) (User-Company) | PIC1 | When I post on Weibo about brand enterprises, I receive personified responses from the brand enterprise accounts. |

| PIC2 | I frequently participate in discussions on Weibo related to enterprise brands. | |

| PIC3 | Through personification communication with enterprises, I feel that I am able to establish a connection with the enterprise. | |

| Attitude (AT) | AT1 | I am highly satisfied with the personified communication behavior of enterprises. |

| AT2 | The personified communication of enterprises has created an impulse for me to purchase their products. | |

| AT3 | I believe that it is a good idea for enterprises to engage in personified communication on social media. | |

| Purchase Intention (PW) | PW1 | Personified communication by enterprises has been helpful for me in making purchasing decisions for their products. |

| PW2 | Personified communication by enterprises has influenced my decision to purchase products from this particular enterprise. | |

| PW3 | When deciding whether to purchase a product, I consider the personified communication behavior of the enterprise. | |

| PW4 | When I decide to purchase products from a brand, the personification communication behavior of the enterprise gives me more confidence in my decision. | |

| Cognitive Need (CN) | CN1 | I am eager to learn more about the products I want to purchase. |

| CN2 | I have a strong interest in the products that I purchase. | |

| CN3 | I enjoy tackling problems that require a lot of thought. |

| Variable | Item | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | PU1 | 0.84 | 0.879 | 0.881 | 0.712 |

| PU2 | 0.85 | ||||

| PU3 | 0.84 | ||||

| Perceived Interaction (PIU) (User–User) | PIU1 | 0.75 | 0.862 | 0.864 | 0.681 |

| PIU2 | 0.88 | ||||

| PIU3 | 0.84 | ||||

| Perceived Interaction (PIC) (User–Company) | PIC1 | 0.83 | 0.896 | 0.898 | 0.746 |

| PIC2 | 0.89 | ||||

| PIC3 | 0.87 | ||||

| Attitude (AT) | AT1 | 0.75 | 0.813 | 0.807 | 0.583 |

| AT2 | 0.79 | ||||

| AT3 | 0.75 | ||||

| Purchase Intention (PW) | PW1 | 0.74 | 0.852 | 0.858 | 0.603 |

| PW2 | 0.74 | ||||

| PW3 | 0.84 | ||||

| PW4 | 0.78 | ||||

| Cognitive Need (CN) | CN1 | 0.84 | 0.842 | 0.852 | 0.592 |

| CN2 | 0.80 | ||||

| CN3 | 0.71 |

| PU | PIU | PIC | AT | PW | CN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | 0.843 | |||||

| Perceived Interaction (PIU) (User–User) | 0.161 | 0.825 | ||||

| Perceived Interaction (PIC) (User-Company) | 0.071 | 0.034 | 0.863 | |||

| Attitude (AT) | 0.191 | 0.245 | 0.226 | 0.763 | ||

| Purchase Intention (PW) | 0.231 | 0.256 | 0.198 | 0.278 | 0.769 | |

| Cognitive Need (CN) | 0.230 | 0.257 | 0.266 | 0.373 | 0.335 | 0.875 |

| Statistical Test | χ2/df | SMRM | RMSEA | AGFI | NFI | RFI | CFI | IFI | PGFI | PNFI | PCFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal Value | <2.00 | <0.08 | <0.05 | >0.80 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.50 | >0.50 | >0.50 |

| Acceptable Value | <3.00 | <0.1 | <0.08 | >0.70 | >0.80 | >0.80 | >0.80 | >0.80 | |||

| Our Value | 1.46 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.67 | 0.76 | 0.79 |

| Path | Effect | Bootstrapping (5000 Samples) | Result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias-Corrected | Percentile | |||||

| 95% CI | 95% CI | |||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||

| PU→AT→PW | total | 0.170 | 0.452 | 0.170 | 0.450 | Exist |

| direct | 0.049 | 0.261 | 0.049 | 0.264 | Exist | |

| indirect | 0.019 | 0.318 | 0.010 | 0.311 | Exist | |

| PIU→AT→PW | total | 0.205 | 0.530 | 0.197 | 0.515 | Exist |

| direct | 0.014 | 0.250 | 0.001 | 0.237 | Exist | |

| indirect | 0.084 | 0.403 | 0.082 | 0.401 | Exist | |

| PIC→AT→PW | total | 0.194 | 0.494 | 0.197 | 0.496 | Exist |

| direct | 0.115 | 0.389 | 0.096 | 0.369 | Exist | |

| indirect | −0.059 | 0.268 | −0.044 | 0.285 | Not Exist | |

| Path | Conditional Indirect Effect | Moderated Mediating Effect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Effect | Standard Error | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | INDEX | Standard Error | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| PU→AT →PW | Low | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.003 | 0.150 | 0.064 | 0.03 | 0.024 | 0.127 |

| High | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.045 | 0.218 | |||||

| PIU→AT →PW | Low | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.022 | 0.150 | 0.013 | 0.04 | −0.069 | 0.011 |

| High | 0.06 | 006 | 0.042 | 0.187 | |||||

| PIC→AT →PW | Low | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.042 | 0.215 | 0.002 | 0.05 | −0.096 | 0.089 |

| High | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.012 | 0.239 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, J.; Zhu, C. Modeling and Quantifying the Impact of Personified Communication on Purchase Behavior in Social Commerce. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080627

Zhao J, Zhu C. Modeling and Quantifying the Impact of Personified Communication on Purchase Behavior in Social Commerce. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(8):627. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080627

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Jie, and Chengxiang Zhu. 2023. "Modeling and Quantifying the Impact of Personified Communication on Purchase Behavior in Social Commerce" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 8: 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080627

APA StyleZhao, J., & Zhu, C. (2023). Modeling and Quantifying the Impact of Personified Communication on Purchase Behavior in Social Commerce. Behavioral Sciences, 13(8), 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080627