The Effect of Social Network Use on Chinese College Students’ Conspicuous Consumption: A Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Social Network Use Intensity Scale

3.2.2. Upward Social Comparison Scale

3.2.3. Life Orientation Test

3.2.4. Conspicuous Consumption Scale

3.3. Procedure and Data Processing

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Deviation Test

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis of Each Variable

4.3. Mediation Model Testing

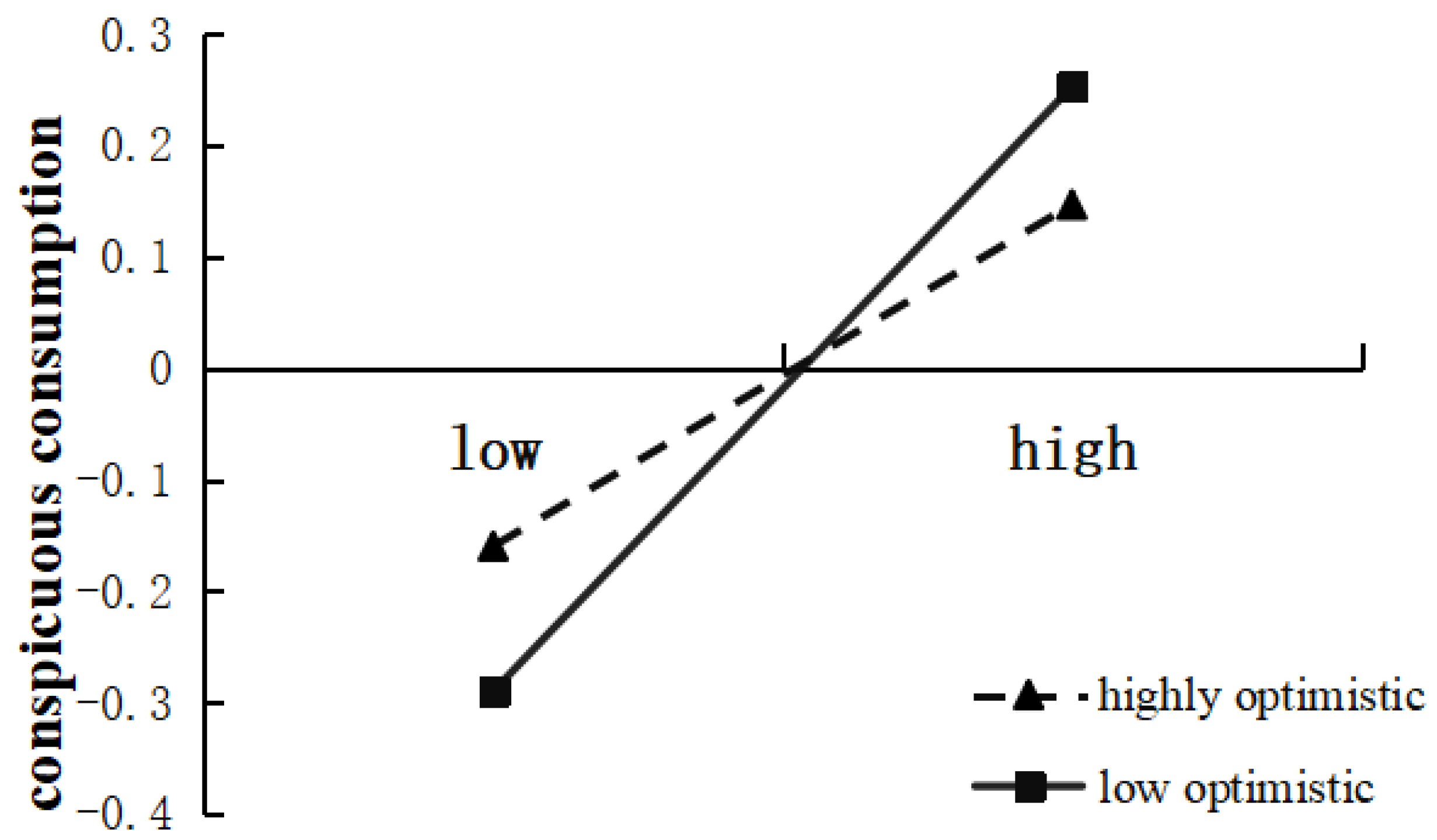

4.4. Moderated Mediation Model Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Government Work Report. 2021. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-03/05/content_5590441.htm (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Bain & Company. Bain and Tmall Luxury Jointly Release 2020 China Luxury Market Research Report for the First Time. 2020. Available online: http://www.bain.com.cn/news_info.php?id=1253 (accessed on 24 September 2022).

- O’Cass, A.; McEwen, H. Exploring consumer status and conspicuous consumption. J. Consum. Behav. 2004, 4, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy Chaudhuri, H.; Mazumdar, S.; Ghoshal, A. Conspicuous consumption orientation: Conceptualisation, scale development and validation. J. Consum. Behav. 2011, 10, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.P. A study on the conspicuous consumption’s impact on middle school students’ self-identity. Educ. Sci. 2014, 30, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. An Empirical Study of the Effects of Vanity and Money Attitudes on College Students’ Propensity to Conspicuous Consumption. Master’s Thesis, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, C.L. Conspicuous consumption in emerging market: The case of Chinese migrant workers. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. On face-work an analysis of ritual elements in social interaction. Psychiatry Interpers. Biol. Process. 1955, 18, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.Q.; Zhou, K.Z.; Su, C.T. Face consciousness and risk aversion: Do they affect consumer decision making? Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 733–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Su, C.T. How face influences consumption: A comparative study of American and Chinese consumers. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2007, 49, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monkhouse, L.L.; Barnes, B.R.; Stephan, U. The influence of face and group orientation on the perception of luxury goods: A four market study of East Asian consumers. Int. Mark. Rev. 2012, 29, 647–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, G.A.; Ponce, H.R. Personality traits influencing young adults’ conspicuous consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 45, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Gao, J.K.; Liu, Z.Y.; Luo, Y.; Chen, M.G.; Bu, L.X. Luxury in emerging markets: An investigation of the role of subjective social class and conspicuous Consumption. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China News. 19-Year-Old Female Student “Naked Loan”: Truly Want to Buy a New Mobile Phone. 2018. Available online: https://www.chinanews.com.cn/m/sh/2018/03-05/8459639.shtml (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Liang, S. The Influence of Social Exclusion on Consumption in Social Media Scene. Ph.D. Thesis, Huangzhong University of Science & Technology, Wuhan, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Danzer, A.M.; Dietz, B.; Gatskova, K.; Schmillen, A. Showing off to the new neighbors? Income, socioeconomic status and consumption patterns of internal migrants. J. Comp. Econ. 2014, 42, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Peng, S.; Dai, S. The impact of social comparison on conspicuous consumption: A psychological compensation perspective. J. Mark. Sci. 2014, 10, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Madzharov, A.V.; Block, L.G.; Morrin, M. The cool scent of power: Effects of ambient scent on consumer preferences and choice behavior. J. Mark. 2015, 79, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, B.; Podoshen, J.S. An examination of materialism, conspicuous consumption and gender differences. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Griskevicius, V. Conspicuous consumption, relationships, and rivals: Women’s luxury products as signals to other women. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 40, 834–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucker, D.D.; Galinsky, A.D.; Dubois, D. Power and consumer behavior: How power shapes who and what consumers value. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 352–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazi, S.; Filieri, R.; Gorton, M. Customers’ motivation to engage with luxury brands on social media. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoux, J.S.; Filiatrault, P.; Chéron, E. The attitudes underlying preferences of young urban educated polish consumers towards products made in western countries. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 1997, 9, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podoshen, J.S.; Andrzejewski, S.A. An examination of the relationships between materialism, conspicuous consumption, impulse buying, and brand loyalty. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2012, 20, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoumrungroje, A. The influence of social media intensity and EWOM on conspicuous consumption. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 148, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, K.; Stephen, A.T. Are close friends the enemy? Online social networks, self-esteem, and self-control. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2013, 40, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.M.; Ellison, N.B. Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2008, 13, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Bierhoff, H.W. The narcissistic millennial generation: A study of personality traits and online behavior on Facebook. J. Adult Dev. 2020, 27, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC). The 48th “Statistical Report on Internet Development in China”. 2021. Available online: http://www.cnnic.cn/hlwfzyj/hlwxzbg/hlwtjbg/202109/t20210915_71543.htm (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Steinfield, C.; Ellison, N.B.; Lampe, C. Social capital, self-esteem, and use of online social network sites: A longitudinal analysis. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 29, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan, J.L.; Gomez, R.; Sparks, L. Disclosures about important life events on Facebook: Relationships with stress and quality of life. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 39, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Moreland, J.J. The dark side of social networking sites: An exploration of the relational and psychological stressors associated with Facebook use and affordances. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moqbel, M.; Kock, N. Unveiling the dark side of social networking sites: Personal and work-related consequences of social networking site addiction. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.G.; Wang, J.W.; Wang, X.N.; Wan, X.J. Exploring factors of user’s peer-influence behavior in social media on purchase intention: Evidence from QQ. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 980–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, R.; Han, S.; Gupta, S. Do friends influence purchases in a social network? Harv. Bus. Sch. Mark. Unit Work. Pap. 2009, 43, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.G.; Strutton, D. Does Facebook usage lead to conspicuous consumption? The role of envy, narcissism and self-promotion. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2016, 10, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, C.; Thai, S.; Lockwood, P.; Kovacheff, C.; Page-Gould, E. When every day is a high school reunion: Social media comparisons and self-esteem. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 121, 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y. How do people compare themselves with others on social network sites?: The case of Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 32, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.N.; Ma, T.Y.; Zhang, H. Social comparison in social network sites: Status quo and prospect. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2019, 6, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, H.T.G.; Edge, N. “They are happier and having better lives than I am”: The impact of using Facebook on perceptions of others’ lives. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2012, 15, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, J.P.; Wheeler, L.; Suls, J. A social comparison theory meta-analysis 60+ years on. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 144, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samra, A.; Warburton, W.A.; Collins, A.M. Social comparisons: A potential mechanism linking problematic social media use with depression. J. Behav. Addict. 2022, 11, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, S.; Yu, G. A review on research of social comparison. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 13, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zoonen, W.; Treem, J.W.; Ter Hoeven, C.L. A tool and a tyrant: Social media and well-being in organizational contexts. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 45, 101300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Vendemia, M.A. Selective self-presentation and social comparison through photographs on social networking sites. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016, 19, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, H.; Gerlach, A.L.; Crusius, J. The interplay between Facebook use, social comparison, envy, and depression. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 9, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjetland, G.J.; Finsers, T.R.; Sivertsen, B.; Colman, I.; Hella, R.T.; Skogen, J.C. Focus on self-presentation on social media across sociodemographic variables, lifestyles, and personalities: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Niu, G.; Fan, C.; Zhou, Z. Passive use of social network site and its relationships with self-esteem and self-concept clarity: A moderated mediation analysis. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2017, 49, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesser, A. Toward a self-evaluation maintenance model of social behavior. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 21, 181–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, N.; Rucker, D.D.; Levav, J.; Galinsky, A.D. The compensatory consumer behavior model: How self-discrepancies drive consumer behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2017, 27, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.Y.; Baskin, E.; Peng, S.Q. Feeling Inferior, Showing Off: The Effect of Nonmaterial Social Comparisons on Conspicuous Consumption. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 90, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussweiler, T. Comparison processes in social judgment: Mechanisms and consequences. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 110, 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.; Yu, G. Social Comparison: Contrast effect or assimilation effect? Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 14, 944–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, J.K.; Carver, C.S. Coping with stress: Divergent strategies of optimists and pessimists. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1257–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R.L. For better or worse: The impact of upward social comparison on self-evaluations. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 119, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.; Sun, X.; Zhou, Z.; Kong, F.; Tian, Y. The impact of social network site (Qzone) on adolescents’ depression: The serial mediation of upward social comparison and self-esteem. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2016, 48, 1282–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z. The mediating effects of social comparison on the relationship between achievement goal and academic self-efficacy: Evidence from the junior high school students. J. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 36, 1413–1420. Available online: http://www.psysci.org/EN/Y2013/V36/I6/1413 (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Gibbons, F.X.; Buunk, B.P. Individual differences in social comparison: Development of a scale of social comparison orientation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.J.; Cheng, H.C. Chinese Revision of Life Orientation Test in junior high school students. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 15, 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chukwuorji, J.C.; Nweke, A.; Iorfa, S.K.; Lloyd, C.J.; Effiong, J.E.; Ndukaihe, I.L.G. Distorted cognitions, substance use and suicide ideation among gamblers: A moderated mediation approach. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 19, 1398–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Cobo, M.J.; Megias, A.; Gomez-Leal, R.; Cabello, R.; Fernandez-Berrocal, P. The role of emotional intelligence and negative affect as protective and risk factors of aggressive behavior: A moderated mediation model. Aggress. Behav. 2018, 44, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, S.D.; Mason, W. Internet research in psychology. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015, 66, 877–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatard, A.; Bocage-Barthélémy, Y.; Selimbegović, L.; Guimond, S. The woman who wasn’t there: Converging evidence that subliminal social comparison affects self-evaluation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 73, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussweiler, T.; Rüter, K.; Epstude, K. The ups and downs of social comparison: Mechanisms of assimilation and contrast. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 87, 832–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.E.; Gosling, S.D.; Graham, L.T. A review of Facebook research in the social sciences. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 7, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Liu, Y. The influence mechanism between passive use of social networks site and preference towards status commodity. J. Inf. Resour. Manag. 2021, 11, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Yang, C. How will Social crowding influence conspicuous consumption: Need for self-expression as the underlying process. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2021, 24, 161–173. [Google Scholar]

- Norlander, T.; Johansson, A.; Bood, S.A. The affective personality: Its relation to quality of sleep, well-being and stress. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2005, 33, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, B.W.C.; Moneta, G.B.; McBride-Chang, C. Think positively and feel positively: Optimism and life satisfaction in late life. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2005, 61, 335–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieswijk, N.; Buunk, B.P.; Steverink, N.; Slaets, J.P. The effect of social comparison information on the life satisfaction of frail older persons. Psychol. Aging 2004, 19, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Gender | 0.74 | 0.44 | 1 | |||||

| 2 Age | 20.08 | 1.44 | −0.11 ** | 1 | ||||

| 3 Intensity of social network use | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.23 ** | 0.03 | 1 | |||

| 4 Conspicuous consumption | 2.89 | 0.66 | 0.01 | 0.14 ** | 0.23 ** | 1 | ||

| 5 Upward social comparison | 3.00 | 0.88 | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.22 ** | 0.33 ** | 1 | |

| 6 Optimistic | 3.34 | 0.60 | 0.11 ** | 0.02 | 0.08 * | −0.05 | −0.21 ** | 1 |

| Predictive Variable | Equation (1) (Calibration: Conspicuous Consumption) | Equation (2) (Calibration: Upward Social Comparison) | Equation (3) (Calibration: Upward Social Comparison; Conspicuous Consumption) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | t | β | p | t | β | p | t | |

| Gender | −0.02 | 0.54 | −0.61 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.33 | −0.02 | 0.46 | −0.75 |

| Age | 0.09 *** | <0.001 | 3.64 | −0.04 | 0.75 | −1.44 | 0.10 *** | <0.001 | 4.27 |

| Social networking site use intensity | 0.25 *** | <0.001 | 6.09 | 0.26 *** | <0.001 | 5.28 | 0.19 *** | <0.001 | 4.81 |

| Upward social comparison | 0.26 *** | <0.001 | 8.57 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.16 | ||||||

| F(3, 713) = 17.69 *** | F(3, 713) = 10.72 *** | F(4, 712) = 32.98 *** | |||||||

| Predictive Variable | Equation (1) (Calibration: Conspicuous Consumption) | Equation (2) (Calibration: Upward Social Comparison) | Equation (3) (Calibration: Upward Social Comparison; Conspicuous Consumption) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | t | β | p | t | β | p | t | |

| Gender | −0.02 | 0.54 | −0.61 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.33 | −0.03 | 0.31 | −1.02 |

| Age | 0.09 *** | <0.001 | 3.64 | −0.04 | 0.75 | −1.44 | 0.10 *** | <0.001 | 4.20 |

| Social networking site use intensity | 0.25 *** | <0.001 | 6.09 | 0.26 *** | <0.001 | 5.28 | 0.19 *** | <0.001 | 4.80 |

| Optimism | 0.01 | 0.81 | 0.24 | ||||||

| Upward social comparison | 0.26 *** | <0.001 | 8.38 | ||||||

| Upward social comparison × optimistic | −0.11 ** | 0.005 | −2.80 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.17 | ||||||

| F(3, 713) = 17.69 *** | F(3, 713) = 10.72 *** | F(6, 710) = 23.47 *** | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, L.; Lu, Z.; Wang, L.; Chen, J.; Tian, L.; Cai, S.; Peng, S. The Effect of Social Network Use on Chinese College Students’ Conspicuous Consumption: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 732. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090732

Xu L, Lu Z, Wang L, Chen J, Tian L, Cai S, Peng S. The Effect of Social Network Use on Chinese College Students’ Conspicuous Consumption: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(9):732. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090732

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Lei, Zhaoxizi Lu, Lingyun Wang, Jiwen Chen, Lan Tian, Shuangshuang Cai, and Shun Peng. 2023. "The Effect of Social Network Use on Chinese College Students’ Conspicuous Consumption: A Moderated Mediation Model" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 9: 732. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090732

APA StyleXu, L., Lu, Z., Wang, L., Chen, J., Tian, L., Cai, S., & Peng, S. (2023). The Effect of Social Network Use on Chinese College Students’ Conspicuous Consumption: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences, 13(9), 732. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090732