Bidirectional Relationship between Adolescent Gender Egalitarianism and Prosocial Behavior

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Gender Differences and Longitudinal Changes in Gender Egalitarianism and Prosocial Behavior

1.2. Role of Gender Egalitarianism in Prosocial Behavior

1.3. Role of Prosocial Behavior in Gender Egalitarianism

1.4. Adolescent Gender as a Moderator

1.5. The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Gender Egalitarianism

2.3.2. Prosocial Behavior

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Missing Data and Attrition Analyses

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

3.3. Gender Differences and Longitudinal Changes

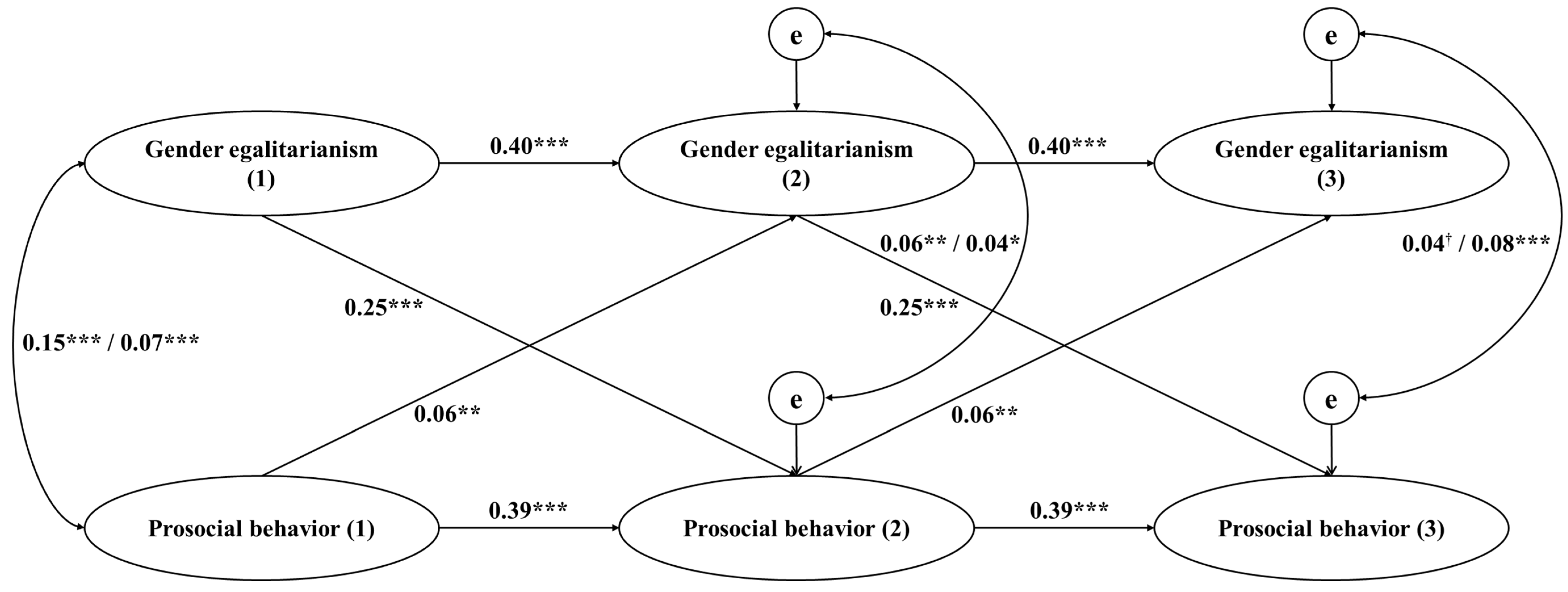

3.4. Multi-Group Cross-Lagged Panel Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Gender and Longitudinal Differences in Gender Egalitarianism and Prosocial Behavior

4.2. Interrelationship between Adolescent Gender Egalitarianism and Prosocial Behavior

4.3. Nonsignificant Moderating Effect of Gender

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eisenberg, N. Children’s needs III: Development, prevention, and intervention. In Prosocial Behavior; Bear, G.G., Minke, K.M., Eds.; National Association of School Psychologists: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 313–324. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Cieciuch, J.; Vecchione, M.; Davidov, E.; Fischer, R.; Beierlein, C.; Ramos, A.; Verkasalo, M.; Lönnqvist, J.-E.; Demirutku, K.; et al. Refining the theory of basic individual values. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 103, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crone, E.A.; Achterberg, M. Prosocial development in adolescence. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 44, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, C.R.; Weber, E.U. Motivating prosocial behavior by leveraging positive self-regard through values affirmation. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 52, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Lv, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yu, X.; Wang, R. Chinese adolescents’ power distance value and prosocial behavior toward powerful people: A longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Fraser, A.M. How much is it going to cost me? Bidirectional relations between adolescents’ moral personality and prosocial behavior. J. Adolesc. 2014, 37, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.X.; Fu, X.; Yu, X.; Lv, Y. Longitudinal relations between adolescents’ materialism and prosocial behavior toward family, friends, and strangers. J. Adolesc. 2018, 62, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruble, D.N.; Alvarez, J.; Bachman, M.; Cameron, J. The development of a sense of “we”: The emergence and implications of children’s collective identity. In The Development of the Social Self; Mark, B., Fabio, S., Eds.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2004; pp. 43–90. ISBN 0-203-39109-8. [Google Scholar]

- Tervooren, A. The embodiment of gender in childhood. In The Palgrave Handbook of Embodiment and Learning; Anja, L., Christoph, W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 245–257. ISBN 978-3-030-93001-1. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, M.B. In-group bias in the minimal intergroup situation: A cognitive-motivational analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, A.; Saral, A.S.; Wu, J. Direct and indirect reciprocity among individuals and groups. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 43, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.N.; Greenstein, T.N. Gender ideology: Components, predictors, and consequences. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2009, 35, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigall, E.A.; Konrad, A.M. Gender role attitudes and careers: A longitudinal study. Sex Roles 2007, 56, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijs, P.; Te Grotenhuis, M.; Scheepers, P.; van den Brink, M. The rise in support for gender egalitarianism in the Netherlands, 1979–2006: The roles of educational expansion, secularization, and female labor force participation. Sex Roles 2019, 81, 594–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, A.D.; Jackson, M. Gender stereotypes, political leadership, and voting behavior in Tunisia. Polit. Behav. 2021, 43, 1037–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, M.; Dotti Sani, G.M. Left behind? Gender gaps in political engagement over the life course in twenty-seven European countries. Soc. Polit. 2018, 25, 254–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, B.D.; Goldberg, L.A.; Solt, F. Public gender Egalitarianism: A dataset of dynamic comparative public opinion toward egalitarian gender roles in the public sphere. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 2023, 53, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucinskas, J. A research note on Islam and gender egalitarianism: An examination of Egyptian and Saudi Arabian youth attitudes. J. Sci. Study Relig. 2010, 49, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, T.J.; Abraham, W.T. Intergenerational continuity in attitudes: A latent variable family fixed-effects approach. J. Fam. Psychol. 2017, 31, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferragut, M.; Blanca, M.J.; Ortiz-Tallo, M. Analysis of adolescent profiles by gender: Strengths, attitudes toward violence and sexism. Span. J. Psychol. 2014, 17, E59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weller, D.; Lagattuta, K.H. Children’s judgments about prosocial decisions and emotions: Gender of the helper and recipient matters. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 2011–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Coutts, A.; Burchell, B.; Kamerāde, D.; Balderson, U. Can active labour market programmes emulate the mental health benefits of regular paid employment? Longitudinal evidence from the United Kingdom. Work Employ. Soc. 2021, 35, 545–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampel, F. Cohort changes in the socio-demographic determinants of gender egalitarianism. Soc. Forces 2011, 89, 961–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgeway, C.L.; Correll, S.J. Unpacking the gender system. Gend. Soc. 2004, 18, 510–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, R.; Rivers, C. Same Difference: How Gender Myths Are Hurting Our Relationships, Our Children, and Our Jobs; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 9780786737895. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, V.R.; Young, S.A.; Schleifer, C.; Brauer, S.G. Exploring Different Patterns of Gender Ideology across College Majors. Sociol. Focus 2023, 56, 20–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.N. Gender ideology construction from adolescence to young adulthood. Soc. Sci. Res. 2007, 36, 1021–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fors Connolly, F.; Goossen, M.; Hjerm, M. Does gender equality cause gender differences in values? Reassessing the gender-equality-personality paradox. Sex Roles 2020, 83, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, I.G.N.E.; Astell-Burt, T.; Cliff, D.P.; Vella, S.A.; Feng, X. Association between green space quality and prosocial behaviour: A 10-year multilevel longitudinal analysis of Australian children. Environ. Res. 2021, 196, 110334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Graaff, J.; Carlo, G.; Crocetti, E.; Koot, H.M.; Branje, S. Prosocial behavior in adolescence: Gender differences in development and links with empathy. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 1086–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, S.X.; Hashi, E.C.; Korous, K.M.; Eisenberg, N. Gender differences across multiple types of prosocial behavior in adolescence: A meta-analysis of the prosocial tendency measure-revised (PTM-R). J. Adolesc. 2019, 77, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, E.; Ehrenreich, S.E.; Beron, K.J.; Underwood, M.K. Prosocial behavior: Long-term trajectories and psychosocial outcomes. Soc. Dev. 2015, 24, 462–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, K.T.; McCormick, E.M.; Telzer, E.H. The neural development of prosocial behavior from childhood to adolescence. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2019, 14, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlo, G.; Crockett, L.J.; Randall, B.A.; Roesch, S.C. A latent growth curve analysis of prosocial behavior among rural adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 2007, 17, 301–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesberg, R.; Keller, J. Donating to the ‘right’ cause: Compatibility of personal values and mission statements of philanthropic organizations fosters prosocial behavior. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 168, 110313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritsenko, V.V.; Kovaleva, Y.V. Correlation of values of culture with standards and types of prosocial behavior of Russians and Belarusians. Psihol. Ž. 2014, 35, 56–67. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Basic values: How they motivate and inhibit prosocial behavior. In Prosocial Motives, Emotions, and Behavior: The Better Angels of Our Nature; Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P.R., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 221–241. ISBN 1-4338-0835-8. [Google Scholar]

- Caviola, L.; Everett, J.A.; Faber, N.S. The moral standing of animals: Towards a psychology of speciesism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 116, 1011–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akrami, N.; Ekehammar, B.; Yang-Wallentin, F. Personality and social psychology factors explaining sexism. J. Individ. Differ. 2011, 32, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckitt, J.; Wagner, C.; Du Plessis, I.; Birum, I. The psychological bases of ideology and prejudice: Testing a dual process model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratto, F.; Sidanius, J.; Levin, S. Social dominance theory and the dynamics of intergroup relations: Taking stock and looking forward. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 17, 271–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehy-Skeffington, J.; Thomsen, L. Egalitarianism: Psychological and socio-ecological foundations. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 32, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, W.; Sheldon, K.M.; Kou, Y. Chinese adolescents with higher social dominance orientation are less prosocial and less happy: A value-environment fit analysis. Int. J. Psychol. 2019, 54, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.T.; Belkin, L.Y. Because I want to share, not because I should: Prosocial implications of gratitude expression in repeated zero-sum resource allocation exchanges. Motiv. Emot. 2019, 43, 824–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yuan, M.; Kou, Y. Disadvantaged early-life experience negatively predicts prosocial behavior: The roles of Honesty-Humility and dispositional trust among Chinese adolescents. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2020, 152, 109608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bem, D.J. Self-perception: An alternative interpretation of cognitive dissonance phenomena. Psychol. Rev. 1967, 74, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basirun, M.; Haryono, S.; Mustofa, Z.; Prajoogo, W. The influence of organizational justice and prosocial behavior toward empathy on the care of Islamic religious patients with welfare moderators. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 926–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Eggum, N.D.; Di Giunta, L. Empathy-related responding: Associations with prosocial behavior, aggression, and intergroup relations. Soc. Issue Policy Rev. 2010, 4, 143–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymond, C.M.; Kenter, J.O.; van Riper, C.J.; Rawluk, A.; Kendal, D. Editorial overview: Theoretical traditions in social values for sustainability. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1173–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, J.; Levin, S.; Liu, J.; Pratto, F. Social dominance orientation, anti-egalitarianism and the political psychology of gender: An extension and cross-cultural replication. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Bernhard, H.; Rockenbach, B. Egalitarianism in young children. Nature 2008, 454, 1079–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H. Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social-Role Interpretation; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 0-89859-804-4. [Google Scholar]

- Löffler, C.S.; Greitemeyer, T. Are women the more empathetic gender? The effects of gender role expectations. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.; Ertac, S.; Gneezy, U.; List, J.A.; Maximiano, S. Gender, competitiveness, and socialization at a young age: Evidence from a matrilineal and a patriarchal society. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2013, 95, 1438–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exner-Cortens, D.; Wright, A.; Claussen, C.; Truscott, E. A systematic review of adolescent masculinities and associations with internalizing behavior problems and social support. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 68, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Bynner, J.; Wiggins, R.; Schoon, I. The measurement and evaluation of social attitudes in two British Cohort Studies. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 107, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.; Seligman, M.E.P. Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 0-19-516703-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich, R.; Becker, M.; Scharf, J. The Development of Gender Role Attitudes During Adolescence: Effects of Sex, Socioeconomic Background, and Cognitive Abilities. J. Youth Adolesc. 2022, 51, 2114–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Jia, Z.; Yan, S. Does gender matter? The relationship comparison of strategic leadership on organizational ambidextrous behavior between male and female CEOs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henningsen, L.; Eagly, A.H.; Jonas, K. Where are the women deans? The importance of gender bias and self-selection processes for the deanship ambition of female and male professors. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 52, 602–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutel, A.M.; Johnson, M.K. Gender and prosocial values during adolescence: A research note. Sociol. Q. 2004, 45, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.B.; Akao, K.A.; Bahner, C.A.; Siriwardana, P. Moral Beliefs Concerning Gender Equality and Progressivism. N. Am. J. Psychol. 2019, 21, 271–284. [Google Scholar]

- Bem, D.J. Self-Perception Theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1972; Volume 6, pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, R. From values to behavior and from behavior to values. In Values and Behavior: Taking a Cross Cultural Perspective; Roccas, S., Sagiv, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 219–235. ISBN 3319563521. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.; Kou, Y.; Yang, Y. Materialistic values among Chinese adolescents: Effects of parental rejection and self-esteem. Child Youth Care Forum 2015, 44, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Shi, X. The impact of China’s one-child policy on intergenerational and gender relations. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2020, 15, 360–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, M.I.T.; Froehlich, L.; Dorrough, A.R.; Martiny, S.E. The hers and his of prosociality across 10 countries. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 60, 1330–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Item |

|---|---|

| Gender egalitarianism | “Less important for a woman to work than for a man” (reverse-coded) |

| “If both work full-time, man should take equal share of chores” | |

| “Women should have same training/career chances as men” | |

| “Should be more women bosses in important jobs” | |

| “Men and women should have chance to do same kind of work” | |

| Prosocial behavior | “I help my friends, even if it is not easy for me” |

| “I really enjoy doing small favors for my friends” | |

| “I go out of my way to cheer up my friends when they seem sad” | |

| “I voluntarily help my friends” | |

| “I always listen to my friends talk about their problems” | |

| “I enjoy being kind to my friends” | |

| “I watch out for my friends” |

| Variable | Model | χ2 | df | p | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender invariance for gender egalitarianism | 1. Configural invariance | 232.78 | 144 | <0.001 | 0.967 | 0.952 | 0.048 | / | / |

| 2. Weak invariance | 267.85 | 156 | <0.001 | 0.958 | 0.944 | 0.051 | 0.009 | 0.003 | |

| 3. Strong invariance | 366.14 | 168 | <0.001 | 0.926 | 0.908 | 0.066 | 0.041 | 0.180 | |

| 4. Partial strong invariance | 278.30 | 162 | <0.001 | 0.957 | 0.944 | 0.052 | 0.01 | 0.004 | |

| Time invariance for gender egalitarianism | 1. Configural invariance | 157.90 | 72 | <0.001 | 0.966 | 0.951 | 0.047 | / | / |

| 2. Weak invariance | 173.09 | 80 | <0.001 | 0.963 | 0.952 | 0.046 | 0.003 | 0.001 | |

| 3. Strong invariance | 208.19 | 90 | <0.001 | 0.954 | 0.946 | 0.049 | 0.012 | 0.002 | |

| 4. Partial strong invariance | 200.51 | 89 | <0.001 | 0.956 | 0.948 | 0.048 | 0.01 | 0.001 | |

| Gender invariance for prosocial behavior | 1. Configural invariance | 612.81 | 360 | <0.001 | 0.966 | 0.960 | 0.051 | / | / |

| 2. Weak invariance | 636.86 | 378 | <0.001 | 0.965 | 0.961 | 0.050 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| 3. Strong invariance | 665.66 | 396 | <0.001 | 0.964 | 0.962 | 0.050 | 0.002 | 0.001 | |

| Time invariance for prosocial behavior | 1. Configural invariance | 327.85 | 180 | <0.001 | 0.980 | 0.976 | 0.039 | / | / |

| 2. Weak invariance | 340.88 | 192 | <0.001 | 0.980 | 0.978 | 0.038 | 0 | 0.001 | |

| 3. Strong invariance | 400.47 | 206 | <0.001 | 0.973 | 0.973 | 0.042 | 0.007 | 0.003 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender egalitarianism at Time 1 | ||||||

| 2. Gender egalitarianism at Time 2 | 0.41 *** | |||||

| 3. Gender egalitarianism at Time 3 | 0.41 *** | 0.41 *** | ||||

| 4. Prosocial behavior at Time 1 | 0.31 *** | 0.27 *** | 0.20 *** | |||

| 5. Prosocial behavior at Time 2 | 0.18 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.20 *** | 0.43 *** | ||

| 6. Prosocial behavior at Time 3 | 0.24 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.42 *** | |

| M | 3.83 | 3.83 | 4.01 | 4.23 | 4.14 | 4.20 |

| S.D. | 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.76 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fu, X.; Fu, R.; Chang, Y.; Yang, Z. Bidirectional Relationship between Adolescent Gender Egalitarianism and Prosocial Behavior. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010033

Fu X, Fu R, Chang Y, Yang Z. Bidirectional Relationship between Adolescent Gender Egalitarianism and Prosocial Behavior. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Xinyuan, Ruoran Fu, Yanping Chang, and Zhixu Yang. 2024. "Bidirectional Relationship between Adolescent Gender Egalitarianism and Prosocial Behavior" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010033