Why Are Young People Willing to Pay for Health? Chained Mediation Effect of Negative Emotions and Information Seeking on Health Risk Perception and Health Consumption Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Health Consumption Behavior

1.2. Health Risk Perception and Health Consumption Behavior

1.3. Mediating Role of Negative Emotions

1.4. Mediating Role of Information Seeking

1.5. The Chained Mediation Role of Negative Emotion and Information Seeking

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Health Risk Perception

2.2.2. Negative Emotion

2.2.3. Information Seeking

2.2.4. Health Consumption Behavior

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

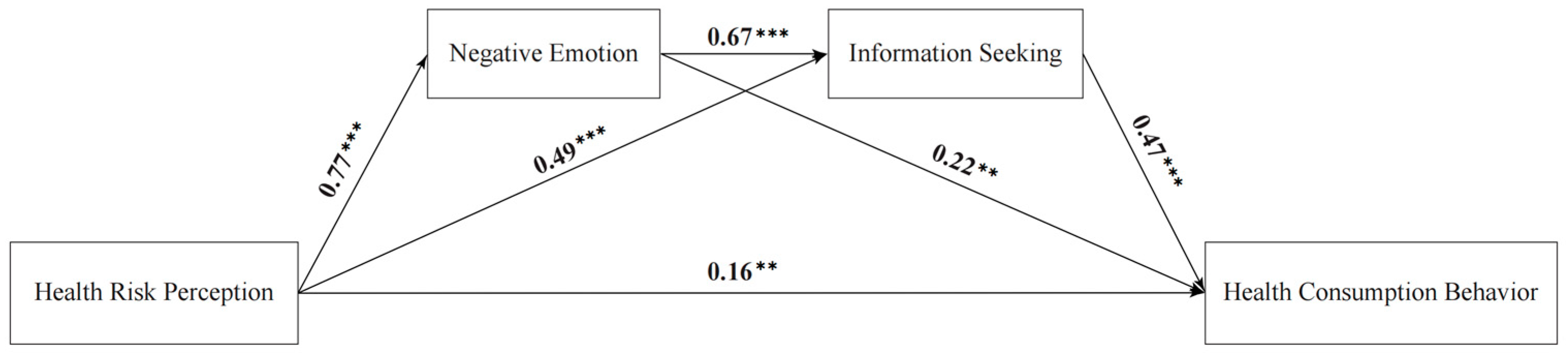

3.1. Hypothesis Testing for Direct Effects

3.2. Single Mediator Effect Test

3.3. Chained Mediation Effect Test

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Chinese Consumers Association: This Year, the Total Revenue of China’s Large Health Industry Is Expected to Reach 9 Trillion Yuan. Available online: https://news.cnr.cn/native/gd/20240830/t20240830_526880090.shtml (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Ferrer, R.; Klein, W.M. Risk perceptions and health behavior. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 5, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, N.T.; Chapman, G.B.; Gibbons, F.X.; Gerrard, M.; McCaul, K.D.; Weinstein, N.D. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: The example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 2007, 26, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, M.; Kothe, E.J.; Mullan, B.A. Predicting intention to receive a seasonal influenza vaccination using Protection Motivation Theory. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 233, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, S.; Arndt, J.; Goldenberg, J.L.; Vess, M.; Vail, K.E., 3rd; Gibbons, F.X.; Rogers, R. The effect of visualizing healthy eaters and mortality reminders on nutritious grocery purchases: An integrative terror management and prototype willingness analysis. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, O.; Zhao, C. How the COVID-19 pandemic influences judgments of risk and benefit: The role of negative emotions. J. Risk Res. 2021, 24, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isen, A.M. Toward understanding the role of affect in cognition. In Handbook of Social Cognition; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1984; Volume 3, pp. 179–236. [Google Scholar]

- Zajonc, R.B. Feeling and Thinking Preferences Need No Inferences. Am. Psychol. 1980, 35, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, J.; Solomon, S.; Kasser, T.; Sheldon, K.M. The Urge to Splurge Revisited: Further Reflections on Applying Terror Management Theory to Materialism and Consumer Behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2004, 14, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasser, T.; Sheldon, K.M. Of wealth and death: Materialism, mortality salience, and consumption behavior. Psychol. Sci. 2000, 11, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, S. From the marketers’ perspective: The interactive media situation in Japan. In Television Goes Digital; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kasl, S.V.; Cobb, S. Health behavior, illness behavior, and sick-role behavior. II. Sick-role behavior. Arch. Environ. Health 1966, 12, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janz, N.K.; Becker, M.H. The Health Belief Model: A decade later. Health Educ. Q. 1984, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratić, M.; Radivojević, A.; Stojiljković, N.; Simović, O.; Juvan, E.; Lesjak, M.; Podovšovnik, E. Should I Stay or Should I Go? Tourists’ COVID-19 Risk Perception and Vacation Behavior Shift. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammouri, A.A.; Neuberger, G. The Perception of Risk of Heart Disease Scale: Development and psychometric analysis. J. Nurs. Meas. 2008, 16, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, G.; Morean, M.E.; Cavallo, D.A.; Camenga, D.R.; Krishnan-Sarin, S. Reasons for Electronic Cigarette Experimentation and Discontinuation Among Adolescents and Young Adults. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2015, 17, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryhurst, S.; Schneider, C.R.; Kerr, J.; Freeman, A.L.J.; Recchia, G.; van der Bles, A.M.; Spiegelhalter, D.; van der Linden, S. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, D.A.K.; Nelson, L.D.; Steele, C.M. Do Messages about Health Risks Threaten the Self? Increasing the Acceptance of Threatening Health Messages Via Self-Affirmation. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 26, 1046–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.R.; Napper, L. Self-affirmation and the biased processing of threatening health-risk information. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 1250–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, N.; Rucker, D.D.; Levav, J.; Galinsky, A.D. The Compensatory Consumer Behavior Model: How self-discrepancies drive consumer behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2016, 27, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.B. Emotion and Personality; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E.J.; Tversky, A. Affect, generalization, and the perception of risk. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 45, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E.M.; Burraston, B.; Mertz, C.K. An emotion-based model of risk perception and stigma susceptibility: Cognitive appraisals of emotion, affective reactivity, worldviews, and risk perceptions in the generation of technological stigma. Risk Anal. 2004, 24, 1349–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P.; Finucane, M.L.; Peters, E.; MacGregor, D.G. Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: Some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Anal. 2004, 24, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrabani, S.; Rosenboim, M.; Shavit, T.; Benzion, U.; Arbiv, M. “Should I Stay or Should I Go?” Risk Perceptions, Emotions, and the Decision to Stay in an Attacked Area. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2018, 26, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, R.J.; Zheng, Y.; ter Huurne, E.; Boerner, F.; Ortiz, S.; Dunwoody, S. After the Flood. Sci. Commun. 2008, 29, 285–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippetoe, P.A.; Rogers, R.W. Effects of components of protection-motivation theory on adaptive and maladaptive coping with a health threat. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, R.W.; Mewborn, C.R. Fear appeals and attitude change: Effects of a threat’s noxiousness, probability of occurrence, and the efficacy of coping responses. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1976, 34, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviours: Broadening and deepening the theory of planned behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40 Pt 1, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, J.S.; Keltner, D. Beyond valence: Toward a model of emotion-specific influences on judgement and choice. Cogn. Emot. 2000, 14, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, R. Anger, fear, uncertainty, and attitudes: A test of the cognitive-functional model. Commun. Monogr. 2010, 69, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amos, C.; Holmes, G.R.; Keneson, W.C. A meta-analysis of consumer impulse buying. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohs, K.D.; Baumeister, R.F. (Eds.) Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 592–594. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Tellegen, A. Toward a consensual structure of mood. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijda, N. The Emotions (Studies in Emotion and Social Interaction); Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Witte, K.; Allen, M. A Meta-Analysis of Fear Appeals: Implications for Effective Public Health Campaigns. Health Educ. Behav. 2000, 27, 591–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.D.; Loiselle, C.G. Health information seeking behavior. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 1006–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.J.; Aloe, A.M.; Feeley, T.H. Risk Information Seeking and Processing Model: A Meta-Analysis. J. Commun. 2014, 64, 20–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Hoque, R.; Wang, S. Investigating the determinants of Chinese adult children’s intention to use online health information for their aged parents. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2017, 102, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willoughby, J.F.; Myrick, J.G. Does Context Matter? Examining PRISM as a Guiding Framework for Context-Specific Health Risk Information Seeking Among Young Adults. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, C.E.; Hong, T. Health information seeking, diet and physical activity: An empirical assessment by medium and critical demographics. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2011, 80, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allington, D.; McAndrew, S.; Moxham-Hall, V.L.; Duffy, B. Media usage predicts intention to be vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 in the US and the UK. Vaccine 2021, 39, 2595–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.L. COVID-19 Information Seeking on Digital Media and Preventive Behaviors: The Mediation Role of Worry. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Walsh, G.; Walsh, G. Electronic Word-of-Mouth: Motives for and Consequences of Reading Customer Articulations on the Internet. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2014, 8, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, H.S.; Voyer, P.A. Word-of-Mouth Processes within a Services Purchase Decision Context. J. Serv. Res. 2016, 3, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohner, G.; Apostolidou, W. Mood and persuasion: Independent effects of affect before and after message processing. J. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 134, 707–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Van Stee, S.K.; Yang, Q. Online Cancer Information Seeking: Applying and Extending the Comprehensive Model of Information Seeking. Health Commun. 2018, 33, 1583–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, R.J.; Dunwoody, S.; Neuwirth, K. Proposed model of the relationship of risk information seeking and processing to the development of preventive behaviors. Environ. Res. 1999, 80 Pt 2, S230–S245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I.; Madden, T.J. Prediction of Goal-Directed Behavior: Attitudes, Intentions, and Perceived Behavioral Control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 8, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brug, J.; Aro, A.R.; Oenema, A.; de Zwart, O.; Richardus, J.H.; Bishop, G.D. SARS risk perception, knowledge, precautions, and information sources, the Netherlands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1486–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-S.; Cho, H.J.J.E.T.S. Factors Affecting Information Seeking and Evaluation in a Distributed Learning Environment. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2011, 14, 213–223. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.t.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Putte, B.; Yzer, M.; Willemsen, M.C.; de Bruijn, G.J. The effects of smoking self-identity and quitting self-identity on attempts to quit smoking. Health Psychol. 2009, 28, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.S.; Chassin, L.; Presson, C.C.; Sherman, S.J. Prospective predictors of quit attempts and smoking cessation in young adults. Health Psychol. 1996, 15, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.A.; Rimal, R.N.; Cho, N. Normative influences and alcohol consumption: The role of drinking refusal self-efficacy. Health Commun. 2013, 28, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romo, L.K. “Above the influence”: How college students communicate about the healthy deviance of alcohol abstinence. Health Commun. 2012, 27, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, D.; Silk, K.J. Social norms, self-identity, and attention to social comparison information in the context of exercise and healthy diet behavior. Health Commun. 2011, 26, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, N.R.; Wingate, L.T. The Influence of Memorable Message Receipt on Dietary and Exercise Behavior among Self-Identified Black Women. Health Commun. 2022, 37, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, D.L.; Prentice-Dunn, S.; Rogers, R.W. A meta-analysis of research on protection motivation theory. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Health Risk Perception | 3.38 | 0.87 | 0.76 | |||

| 2. Information Seeking | 3.54 | 0.93 | 0.62 ** | 0.86 | ||

| 3. Negative Emotion | 3.43 | 0.88 | 0.62 ** | 0.69 ** | 0.82 | |

| 4. Health Consumption Behavior | 3.63 | 0.86 | 0.53 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.58 ** | 0.81 |

| Std. Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | Unstd. Estimate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Risk Perception | ---> | Negative Emotions | 0.70 | 0.06 | 13.02 | <0.001 | 0.76 |

| Health Risk Perception | ---> | Information Seeking | 0.36 | 0.06 | 7.94 | <0.001 | 0.49 |

| Health Risk Perception | ---> | Health Consumption Behavior | 0.13 | 0.07 | 2.36 | <0.01 | 0.16 |

| Negative Emotions | ---> | Information Seeking | 0.55 | 0.06 | 11.97 | <0.001 | 0.67 |

| Negative Emotions | ---> | Health Consumption Behavior | 0.18 | 0.07 | 3.02 | <0.01 | 0.22 |

| Information Seeking | ---> | Health Consumption Behavior | 0.49 | 0.07 | 6.48 | <0.001 | 0.47 |

| Bootstrapping | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point Estimates | Product of Coefficients | Percentile 95% CI | Bias-Corrected 95% CI | Two- Tailed Sign | ||||

| SE | Z | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||

| HRP--->NE --->HCB | 0.13 | 0.05 | 2.72 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.03 | 0.22 | <0.05 |

| HRP--->IS --->HCB | 0.18 | 0.04 | 4.32 | 0.11 | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.28 | <0.001 |

| HRP--->NE--->IS--->HCB | 0.19 | 0.04 | 4.68 | 0.12 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.28 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Li, Y. Why Are Young People Willing to Pay for Health? Chained Mediation Effect of Negative Emotions and Information Seeking on Health Risk Perception and Health Consumption Behavior. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 879. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100879

Li J, Li Y. Why Are Young People Willing to Pay for Health? Chained Mediation Effect of Negative Emotions and Information Seeking on Health Risk Perception and Health Consumption Behavior. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(10):879. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100879

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jia, and Yingyi Li. 2024. "Why Are Young People Willing to Pay for Health? Chained Mediation Effect of Negative Emotions and Information Seeking on Health Risk Perception and Health Consumption Behavior" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 10: 879. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100879

APA StyleLi, J., & Li, Y. (2024). Why Are Young People Willing to Pay for Health? Chained Mediation Effect of Negative Emotions and Information Seeking on Health Risk Perception and Health Consumption Behavior. Behavioral Sciences, 14(10), 879. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100879