Factors Influencing Public Donation Intention during Major Public Health Emergencies and Their Interactions: Evidence from China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

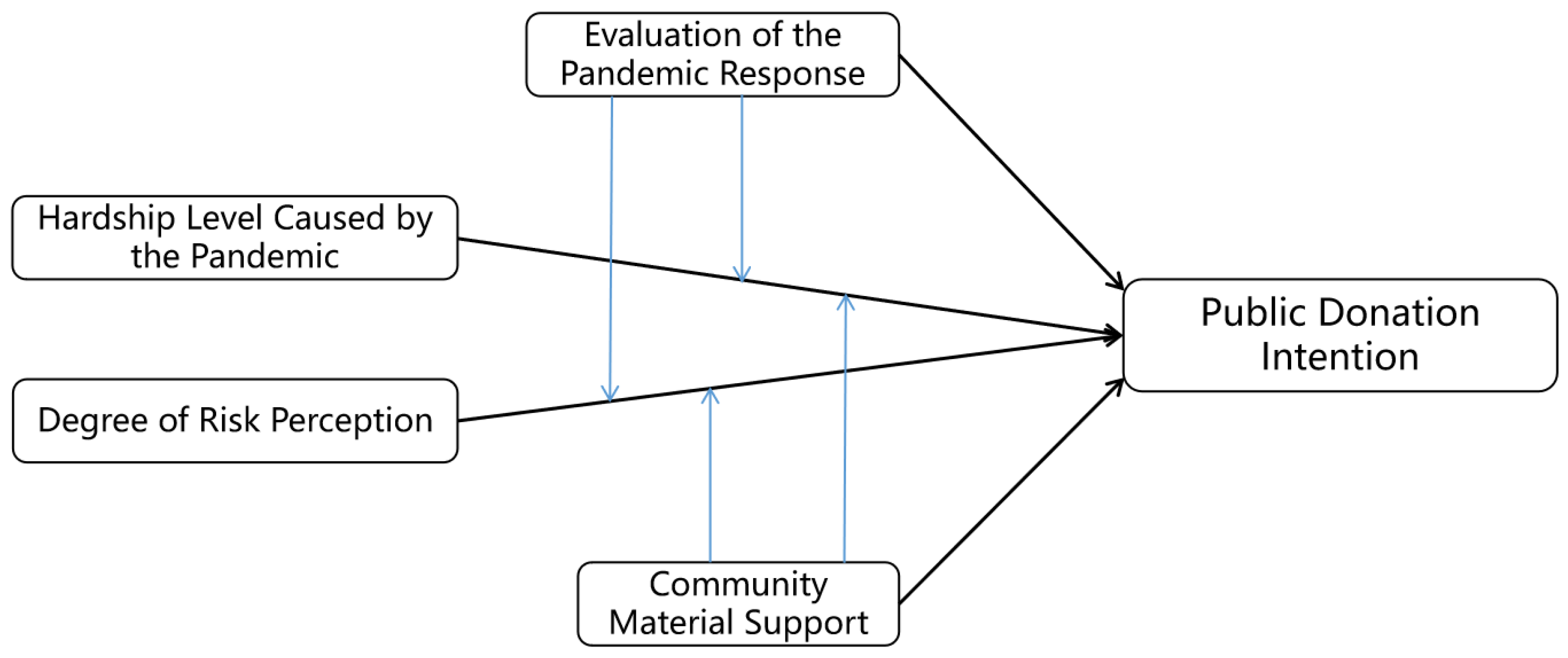

3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

3.1. Theoretical Analysis

3.2. Research Hypotheses

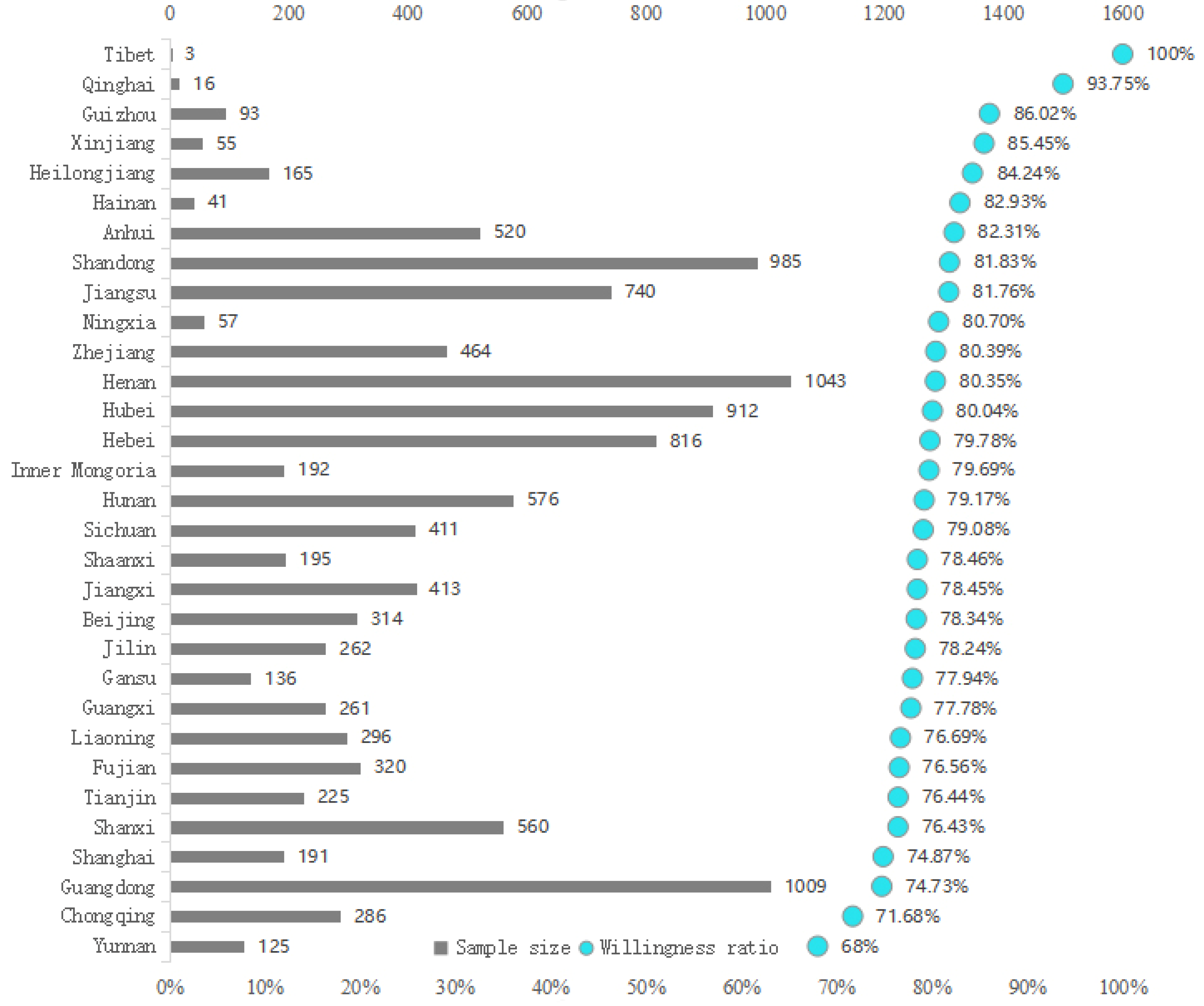

4. Data and Methods

4.1. Data Source

4.2. Variable Measurement

4.2.1. Dependent Variable

4.2.2. Independent Variables

4.2.3. Control Variables

4.2.4. Interaction Terms

4.3. Model Construction

5. Results

5.1. Baseline Regression Model Analysis

5.2. Regression Model Analysis with Moderating Effects

6. Conclusions and Discussion

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kickbusch, I.; Leung, G.M.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Matsoso, M.P.; Ihekweazu, C.; Abbasi, K. COVID-19: How a Virus Is Turning the World Upside Down. BMJ 2020, 369, m1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q. Out of the Shadows: Impact of SARS Experience on Chinese Netizens’ Willingness to Donate for COVID-19 Pandemic Prevention and Control. China Econ. Rev. 2022, 73, 101790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagefka, H.; James, T. The Psychology of Charitable Donations to Disaster Victims and Beyond. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2015, 9, 155–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.R.; McSweeney, A. Charitable Giving: The Effectiveness of a Revised Theory of Planned Behaviour Model in Predicting Donating Intentions and Behaviour. J. Community Appl. Soc. 2007, 17, 363–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, B.H.; Hartwick, J.; Warshaw, P.R. The Theory of Reasoned Action: A Meta-Analysis of Past Research with Recommendations for Modifications and Future Research. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.; Webb, T.L. The Intention–Behavior Gap. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2016, 10, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.; Ferris, J.M. Social Capital and Philanthropy: An Analysis of the Impact of Social Capital on Individual Giving and Volunteering. Nonprof. Volunt. Sec. Q. 2007, 36, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesch, D.J.; Rooney, P.M.; Steinberg, K.S.; Denton, B. The Effects of Race, Gender, and Marital Status on Giving and Volunteering in Indiana. Nonprof. Volunt. Sec. Q. 2006, 35, 565–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, S.T. An Econometric Analysis of Household Donations in the USA. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2002, 9, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, S.K.; Henley, W.H. Determinants of Charitable Donation Intentions: A Structural Equation Model. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2008, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Li, P.; Ju, F. The Divergent Effects of the Public’s Sense of Power on Donation Intention. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schliesser, E. Reading Adam Smith after Darwin: On the Evolution of Propensities, Institutions, and Sentiments. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2011, 77, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaskas, S.; Panagiotarou, A.; Rigou, M. Impact of Personality Traits on Small Charitable Donations: The Role of Altruism and Attitude towards an Advertisement. Societies 2023, 13, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, R. Who Gives What and When? A Scenario Study of Intentions to Give Time and Money. Soc. Sci. Res. 2010, 39, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.-C.; Chiu, C.L.; Mansumitrchai, S.; Yuan, Z.; Zhao, N.; Zou, J. The Influence of Signals on Donation Crowdfunding Campaign Success during COVID-19 Crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 7715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Liu, N.; Luo, C.; Wang, L. Effects of the Severity of Collective Threats on People’s Donation Intention. Psychol. Market. 2021, 38, 1426–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Schaller, M.; Houlihan, D.; Arps, K.; Fultz, J.; Beaman, A.L. Empathy-Based Helping: Is It Selflessly or Selfishly Motivated? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D.; Batson, J.G.; Griffitt, C.A.; Barrientos, S.; Brandt, J.R.; Sprengelmeyer, P.; Bayly, M.J. Negative-State Relief and the Empathy—Altruism Hypothesis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickert, S.; Sagara, N.; Slovic, P. Affective Motivations to Help Others: A Two-stage Model of Donation Decisions. J. Behav. Decis. Making 2011, 24, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaskas, S.; Rigou, M.; Xenos, M.; Mallas, A. Behavioral Intentions to Donate Blood: The Interplay of Personality, Emotional Arousals, and the Moderating Effect of Altruistic versus Egoistic Messages on Young Adults. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piff, P.K.; Dietze, P.; Feinberg, M.; Stancato, D.M.; Keltner, D. Awe, the Small Self, and Prosocial Behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 108, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stellar, J.E.; Gordon, A.M.; Piff, P.K.; Cordaro, D.; Anderson, C.L.; Bai, Y.; Maruskin, L.A.; Keltner, D. Self-Transcendent Emotions and Their Social Functions: Compassion, Gratitude, and Awe Bind Us to Others through Prosociality. Emot. Rev. 2017, 9, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, A.; Lee, S. Donor Trust and Relationship Commitment in the UK Charity Sector: The Impact on Behavior. Nonprof. Volunt. Sec. Q. 2004, 33, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, S.; Falk, A.; Heidhues, P.; Jayaraman, R.; Teirlinck, M. Defaults and Donations: Evidence from a Field Experiment. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2019, 101, 808–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirana, A.F.; Azzahro, F.; Handayani, P.W.; Fitriani, W.R. Trust and Distrust: The Antecedents of Intention to Donate in Digital Donation Platform. In Proceedings of the 2020 Fifth International Conference on Informatics and Computing (ICIC), Gorontalo, Indonesia, 3–4 November 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Mao, Y.; Liu, C. Understanding the Intention to Donate Online in the Chinese Context: The Influence of Norms and Trust. Cyberpsychology 2022, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.R. Psychological Models of the Justice Motive: Antecedents of Distributive and Procedural Justice. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, K.S.; McGuirk, A.M.; Steinberg, R. Further Evidence on the Dynamic Impact of Taxes on Charitable Giving. Natl. Tax J. 1997, 50, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, T.; Lloyd, T. Why Rich People Give; Association of Charitable Foundations: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Duquette, N.J. Do Tax Incentives Affect Charitable Contributions? Evidence from Public Charities’ Reported Revenues. J. Public Econ. 2016, 137, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adena, M.; Huck, S. Voluntary ‘Donations’ versus Reward-Oriented ‘Contributions’: Two Experiments on Framing in Funding Mechanisms. Exp. Econ. 2022, 25, 1399–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charness, G.; Holder, P. Charity in the Laboratory: Matching, Competition, and Group Identity. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 1398–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adena, M.; Hakimov, R.; Huck, S. Charitable Giving by the Poor: A Field Experiment in Kyrgyzstan. Manag. Sci. 2024, 70, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Mao, R.; Ke, Z. Charity Misconduct on Public Health Issues Impairs Willingness to Offer Help. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 13039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-Y.; Huang, J.-T.; Kao, A.-P. An Analysis of the Peer Effects in Charitable Giving: The Case of Taiwan. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2004, 25, 483–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Graddy, E. Social Capital, Volunteering, and Charitable Giving. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2008, 19, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X. Confucianism and Its Modern Values: Confucian Moral, Educational and Spiritual Heritages Revisited. J. Beliefs Values 1999, 20, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wax, A.L. Social Welfare, Human Dignity, and the Puzzle of What We Owe Each Other. Harv JL Pub Pol’y 2003, 27, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, M.H.; Wiepking, P. National Campaigns for Charitable Causes: A Literature Review. Nonprof. Volunt. Sec. Q. 2013, 42, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, E.; Baier, A.; Holzmeister, F.; Jaber-Lopez, T.; Struwe, N. Long Term Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social Concerns. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 743054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, F.L. Psychosocial Homeostasis and Jen: Conceptual Tools for Advancing Psychological Anthropology. Am. Anthropol. 1971, 73, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, R.; Schuyt, T. And Who Is Your Neighbor? Explaining Denominational Differences in Charitable Giving and Volunteering in the Netherlands. Rev. Relig. Res. 2008, 50, 74–96. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, E.F.; Bachmeier, M.D.; Wood, J.R.; Craft, E.A. Volunteering and Charitable Giving: Do Religious and Associational Ties Promote Helping Behavior? Nonprof. Volunt. Sec. Q. 1995, 24, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Chakrabarti, S. Charity Donor Behavior: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2023, 35, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, R.; Wiepking, P. A Literature Review of Empirical Studies of Philanthropy: Eight Mechanisms That Drive Charitable Giving. Nonprof. Volunt. Sec. Q. 2011, 40, 924–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavel, J.J.V.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Crockett, M.J.; Crum, A.J.; Douglas, K.M.; Druckman, J.N. Using Social and Behavioural Science to Support COVID-19 Pandemic Response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D.; Ahmad, N. Empathy-induced Altruism in a Prisoner’s Dilemma II: What If the Target of Empathy Has Defected? Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 31, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J.; Sommerville, J.A. Shared Representations between Self and Other: A Social Cognitive Neuroscience View. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2003, 7, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R. Why Urban Poor Donate: A Study of Low-Income Charitable Giving in London. Nonprof. Volunt. Sec. Q. 2012, 41, 870–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.-M.; You, S.-H. Assessing Risk Perception and Behavioral Responses to Influenza Epidemics: Linking Information Theory to Probabilistic Risk Modeling. Stoch. Env. Res. Risk A. 2014, 28, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhong, X.; Fu, H.; Zhang, H.; Hu, R.; Li, J.; Chen, C.; Wang, K. Risk Perception and Public Pandemic Fatigue: The Role of Perceived Stress and Preventive Coping. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2023, 2023, 1941–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, A.; Gershon, R.; Gneezy, A. Increased Generosity under COVID-19 Threat. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, R.; Wiepking, P. Testing Mechanisms for Philanthropic Behaviour. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2011, 16, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, A.; Fischbacher, U. A Theory of Reciprocity. Games Econom. Behav. 2006, 54, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaeman, D.; Sulaeman, J. The Effect of Social Media on the Ethnic Dynamics in Donations to Disaster Relief Efforts. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Shao, M.; Liu, R.; Wu, X.; Zheng, K. Risk Perception, Perceived Government Coping Validity, and Individual Response in the Early Stage of the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfinch, S.; Taplin, R.; Gauld, R. Trust in Government Increased during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Australia and New Zealand. Aust. J. Publ. Admin. 2021, 80, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroom, V.H. Leadership and the Decision-Making Process. Organ. Dyn. 2000, 28, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. Central Problems in Social Theory: Action, Structure, and Contradiction in Social Analysis; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1979; Volume 241. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Li, Y.; Wei, L. Positive Sentiment and the Donation Amount: Social Norms in Crowdfunding Donations during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 818510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambor, T.; Clark, W.R.; Golder, M. Understanding Interaction Models: Improving Empirical Analyses. Polit. Anal. 2006, 14, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einolf, C.J. Cross-National Differences in Charitable Giving in the West and the World. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2017, 28, 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollhardt, J.R. Altruism Born of Suffering and Prosocial Behavior Following Adverse Life Events: A Review and Conceptualization. Soc. Justice Res. 2009, 22, 53–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierlach, E.; Belsher, B.E.; Beutler, L.E. Cross-cultural Differences in Risk Perceptions of Disasters. Risk Anal. Int. J. 2010, 30, 1539–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmelmeier, M.; Jambor, E.E.; Letner, J. Individualism and Good Works: Cultural Variation in Giving and Volunteering across the United States. J. Cross. Cult. Psychol. 2006, 37, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Assignment/Value Range | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Donation Intention | No = 0 | 21.03 |

| Yes = 1 | 78.97 | ||

| Control Variables | Gender | Female = 0 | 44.49 |

| Male = 1 | 55.51 | ||

| Age Group | 14–17 years = 1 | 3.96 | |

| 18–29 years = 2 | 60.72 | ||

| 30–39 years = 3 | 21.00 | ||

| 40–49 years = 4 | 7.34 | ||

| 50–59 years = 5 | 3.33 | ||

| 60 years and above = 6 | 3.65 | ||

| Marital Status | Unmarried = 0 | 60.53 | |

| Married = 1 | 39.47 | ||

| Household Registration Type | Agricultural registration = 0 | 52.81 | |

| Non-Agricultural registration = 1 | 47.19 | ||

| Years of Education | Elementary school and below = 6 | 3.39 | |

| Junior high school = 9 | 6.88 | ||

| High school/Technical secondary school = 12 | 16.54 | ||

| Junior college = 14 | 21.30 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree = 16 | 42.00 | ||

| Master’s degree and above = 18 | 9.89 | ||

| Family Economic Status | Poor = 1 | 12.12 | |

| Subsistence = 2 | 56.40 | ||

| Comfortable = 3 | 30.05 | ||

| Wealthy = 4 | 1.42 | ||

| Independent Variables | Hardship Level Caused by the Pandemic | Low = 0 | 51.57 |

| High = 1 | 48.43 | ||

| Degree of Risk Perception | Low = 0 | 50.57 | |

| High = 1 | 49.43 | ||

| Community Material Support | Without = 0 | 72.42 | |

| With = 1 | 27.58 | ||

| Evaluation of the Pandemic Response | Low = 0 | 34.64 | |

| High = 1 | 65.36 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | |

| Control Variables | ||||

| Gender (Female) | 0.736 *** | 0.750 *** | 0.753 *** | 0.750 *** |

| Age Group (14–17 years) | ||||

| 18–29 years | 0.974 | 0.922 | 0.934 | 0.923 |

| 30–39 years | 0.916 | 0.867 | 0.877 | 0.869 |

| 40–49 years | 0.861 | 0.843 | 0.843 | 0.844 |

| 50–59 years | 0.592 *** | 0.602 *** | 0.605 *** | 0.603 *** |

| 60 years and above | 0.564 *** | 0.630 *** | 0.641 ** | 0.627 *** |

| Marital Status (Unmarried) | 1.321 *** | 1.219 ** | 1.220 ** | 1.218 ** |

| Household Registration Type (Agricultural Registration) | 0.972 | 1.036 | 1.035 | 1.033 |

| Years of Education | 1.089 *** | 1.104 *** | 1.102 *** | 1.105 *** |

| Family Economic Status | 1.169 *** | 1.209 *** | 1.209 *** | 1.209 *** |

| Independent Variables | ||||

| Hardship Level Caused by the Pandemic (Low) | 1.557 *** | 1.184 ** | 1.455 *** | |

| Degree of Risk Perception (Low) | 1.428 *** | 1.479 *** | 1.423 *** | |

| Community Material Support (Without) | 1.392 *** | 1.396 *** | 1.211 ** | |

| Evaluation of the Pandemic Response (Low) | 2.037 *** | 1.665 *** | 2.040 *** | |

| Interaction Terms | ||||

| Hardship Level Caused by the Pandemic × Evaluation of the Pandemic Response | 1.642 *** | |||

| Degree of Risk Perception × Evaluation of the Pandemic Response | 0.926 | |||

| Hardship Level Caused by the Pandemic × Community Material Support | 1.343 *** | |||

| Degree of Risk Perception × Community Material Support | 1.02 | |||

| Constant | 0.959 | 0.307 *** | 0.361 *** | 0.315 ** |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.021 | 0.052 | 0.054 | 0.052 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, M.; Tian, B. Factors Influencing Public Donation Intention during Major Public Health Emergencies and Their Interactions: Evidence from China. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100927

Zhao M, Tian B. Factors Influencing Public Donation Intention during Major Public Health Emergencies and Their Interactions: Evidence from China. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(10):927. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100927

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Minghua, and Beihai Tian. 2024. "Factors Influencing Public Donation Intention during Major Public Health Emergencies and Their Interactions: Evidence from China" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 10: 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100927

APA StyleZhao, M., & Tian, B. (2024). Factors Influencing Public Donation Intention during Major Public Health Emergencies and Their Interactions: Evidence from China. Behavioral Sciences, 14(10), 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100927