Traditional Value Identity and Mental Health Correlation Among Chinese Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Studies on Traditional Values

1.2. Research Related to Traditional Values and Mental Health

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Traditional Values Scale

2.2.2. Mental Health Scale for Secondary School Students

2.2.3. Statistical Analysis of Data

3. Results

3.1. Overall Situation of Adolescents’ Identification with Traditional Values

3.2. Demographic Group-Based Comparison of Adolescents’ Identification with Traditional Values

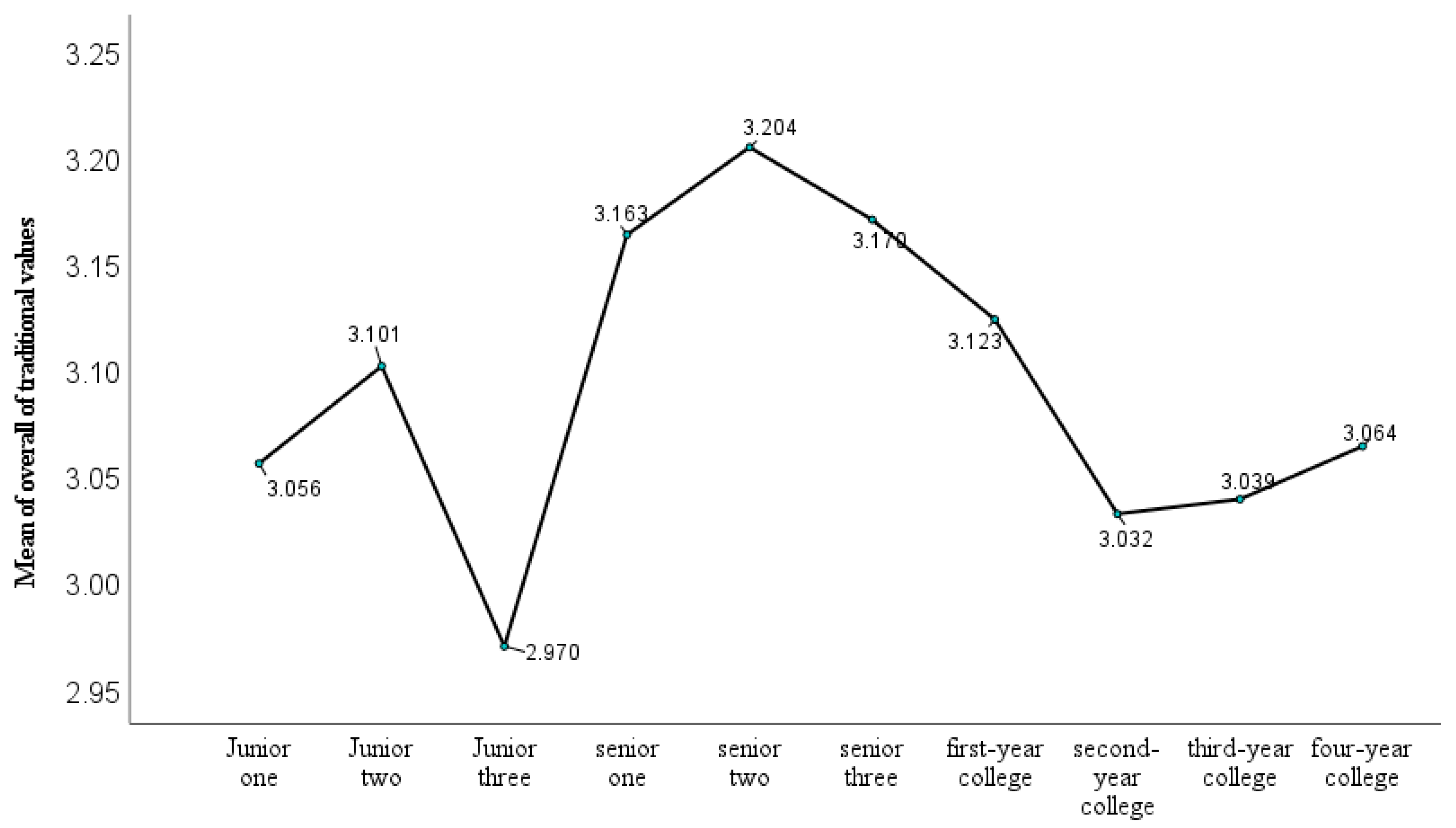

3.3. Trends in the Identification of Traditional Values Among Adolescents by Grade Level

3.4. Variations in Adolescents’ Identification with Traditional Values Across Educational Stages

3.5. Correlation Analysis Between Adolescents’ Identification with Traditional Values and Mental Health Levels

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chang, W.C.; Wong, W.K.; Koh, J.B.K. Chinese Values in Singapore: Traditional and Modern. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 6, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, H. The Historical Experience of Confucianism and the Construction of the Socialist Core Values. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Advances in Management, Arts and Humanities Science, Taichung, Taiwan, 10–11 December 2016; Atlantis Press: Taichung, Taiwan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R.; Baker, W.E. Modernization, Cultural Change, and the Persistence of Traditional Values. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2000, 65, 19–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, K. Elder Respect: Exploration of Ideals and Forms in East Asia. J. Aging Stud. 2001, 15, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.-M.; Hong, Y.-J.; Xiao, H.-W.; Lian, R. Honesty-Humility and Dispositional Awe in Confucian Culture: The Mediating Role of Zhong-Yong Thinking Style. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 167, 110228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulich, S.J.; Zhang, R. The Multiple Frames of ‘Chinese’ Values: From Tradition to Modernity and Beyond. In Oxford Handbook of Chinese Psychology; Bond, M.H., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Hong Kong, China, 2012; pp. 241–278. ISBN 978-0-19-954185-0. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, V.S. A Comparison of Personal Values of Chinese and Americans. Ph.D. Thesis, California School of Professional Psychology, Fresno, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, M.H. (Ed.) Chinese values. In The Handbook of Chinese Psychology; Oxford University Press: Hong Kong, China, 1996; pp. 208–226. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z. An Investigation of Traditional Life Values of Chinese College Students. J. Southwest China Norm. Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2001, 27, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Xia, F.; Wu, C.; Yu, S. A Brief Discussion on the Influence of University on the Traditional Value Identity of Adolescents. Sci. Technol. Perspect. 2015, 22, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.; Yang, Y.; Liang, S. Acceptance of Traditional Values and Its Impact on Mental Health. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 18, 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Yip, K.-S. Taoism and Its Impact on Mental Health of the Chinese Communities. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2004, 50, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Swanson, D.P.; Rogge, R.D. From Zen to Stigma: Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, and Their Cross-cultural Links to Mental Health. J. Couns. Dev. 2024, 102, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-Y.; Swanson, D.P.; Rogge, R.D. The Three Teachings of East Asia (TTEA) Inventory: Developing and Validating a Measure of the Interrelated Ideologies of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 626122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V. Cultural Influence on Psychoeducation in Hong Kong. Int. Psychiatry 2010, 7, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kuo, C.-L.; Kavanagh, K.H. Chinese Perspectives on Culture and Mental Health. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 1994, 15, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.Y. An Overview of the Relationship between Traditional Values and Happiness of College Students. Educ. Vert. Horiz. 2014, 7, 309. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G. Chinese Psychology and Behavior: A Study of Localization; Renmin University of China Press: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; He, E. Development and Standardization of a Mental Health Scale for Chinese Secondary School Students. Psychosoc. Sci. 1997, 4, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K. Survey on Traditional Values of Adolescents. J. Neijiang Norm. Coll. 2017, 32, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, X.; Ng, S.H. Filial Obligations and Expectations in China: Current Views from Young and Old People in Beijing. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 2, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solhi, M.; Taghipour, A.; Ebadiazar, F.; Asgharnejad Farid, A.; Mahdizadeh, M. Experience of Adolescentes of Promoting Family for Their Social Health: A Qualitative Study. Shiraz E-Med. J. 2017, 18, e58664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.-M. The Impact of Harmony on Chinese Conflict Management. Chin. Confl. Manag. Resolut. 2002, 2002, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Fuligni, A.J. Authority, Autonomy, and Family Relationships among Adolescents in Urban and Rural China. J. Res. Adolesc. 2006, 16, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chang, L.; He, Y. The Peer Group as a Context: Mediating and Moderating Effects on Relations between Academic Achievement and Social Functioning in Chinese Children. Child Dev. 2003, 74, 710–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, S. Gender Role Attitudes and Male-Female Income Differences in China. J. Chin. Sociol. 2020, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Pang, X.; Zhang, L.; Medina, A.; Rozelle, S. Gender Inequality in Education in China: A Meta-Regression Analysis. Contemp. Econ. Policy 2014, 32, 474–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Abad, D.D. Family Background and the Choice of Hispanic Philology among Liberal Arts Students in China. Int. J. Chin. Educ. 2023, 12, 2212585X231221824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, G.P.; Carlo, G.; Mahrer, N.E.; Davis, A.N. The Socialization of Culturally Related Values and Prosocial Tendencies Among Mexican-American Adolescents. Child Dev. 2016, 87, 1758–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, F.; Magnusson, J.; Klemera, E.; Spencer, N.; Morgan, A. HBSC England National Report: Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC): World Health Organization Collaborative Cross National Study; University of Hertfordshire: Hatfield, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, G.; Dumontheil, I. Development of Risk-Taking, Perspective-Taking, and Inhibitory Control During Adolescence. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2016, 41, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merikangas, K.R.; He, J.; Burstein, M.; Swanson, S.A.; Avenevoli, S.; Cui, L.; Benjet, C.; Georgiades, K.; Swendsen, J. Lifetime Prevalence of Mental Disorders in U.S. Adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2010, 49, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Wardenaar, K.J.; Xu, G.; Tian, H.; Schoevers, R.A. Mental Health Stigma and Mental Health Knowledge in Chinese Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, X.-M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W. Mental Health-Related Stigma in China. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 39, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodhi, B. The Noble Eightfold Path: The Way to the End of Suffering; Buddhist Publication Society: Kandy, Sri Lanka, 2010; ISBN 955-24-0116-X. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Cui, H. On the Value of the Chinese Pre-Qin Confucian Thought of “Harmony” for Modern Public Mental Health. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 870828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, J.S.; Wang, X. When the West Meets the East: Cultural Clash and Its Impacts on Anomie in a Sample of Chinese Adolescents. Deviant Behav. 2019, 40, 1187–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Values Dimensions | 1 Familialism | 2 Humility and Respect | 3 Face-Saving Relations | 4 Unity and Harmony | 5 Hard Work | 6 Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | 3.39 ± 0.42 | 3.00 ± 0.48 | 2.80 ± 0.49 | 3.40 ± 0.46 | 2.85 ± 0.61 | 3.13 ± 0.35 |

| Comparisons | 1 > 2, 1 > 3, 1 > 5, 2 > 3, 2 < 4, 2 > 5, 3 < 4, 4 > 5 (all p-values < 0.001) | |||||

| Variables | Junior School (N = 146) | High School (N = 139) | College (N = 204) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | F | |

| Familialism | 3.25 ± 0.351 | 3.36 ± 0.461 | 3.51 ± 0.404 | 16.306 *** |

| Humility and respect | 3.04 ± 0.381 | 3.18 ± 0.418 | 2.84 ± 0.538 | 24.305 *** |

| Face-saving relations | 2.91 ± 0.421 | 2.98 ± 0.450 | 2.62 ± 0.489 | 31.513 *** |

| Unity and harmony | 3.30 ± 0.424 | 3.38 ± 0.474 | 3.48 ± 0.463 | 6.721 ** |

| Hard work | 2.71 ± 0.578 | 2.98 ± 0.597 | 2.85 ± 0.620 | 7.366 ** |

| Overall | 3.10 ± 0.277 | 3.21 ± 0.351 | 3.10 ± 0.389 | 5.209 * |

| Familialism | Humility and Respect | Face-Saving Relations | Unity and Harmony | Hard Work | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health | −0.291 ** | −0.238 ** | −0.188 ** | −0.264 ** | −0.110 * | −0.215 ** |

| Output Variable | Predictor Variable | B-Value | t | R2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health | Overall traditional values | −0.449 | −7.324 *** | 0.097 | 53.637 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ren, G.; Yang, G.; Chen, J.; Xu, Q. Traditional Value Identity and Mental Health Correlation Among Chinese Adolescents. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1079. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111079

Ren G, Yang G, Chen J, Xu Q. Traditional Value Identity and Mental Health Correlation Among Chinese Adolescents. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(11):1079. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111079

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Guofang, Guanghui Yang, Junbo Chen, and Qianru Xu. 2024. "Traditional Value Identity and Mental Health Correlation Among Chinese Adolescents" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 11: 1079. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111079

APA StyleRen, G., Yang, G., Chen, J., & Xu, Q. (2024). Traditional Value Identity and Mental Health Correlation Among Chinese Adolescents. Behavioral Sciences, 14(11), 1079. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111079