Do K-Pop Consumers’ Fandom Activities Affect Their Happiness, Listening Intention, and Loyalty?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Research Questions

- RQ 1. How do the fandom activities of K-pop consumers affect their happiness and CCM listening intention?

- RQ 2. How does the happiness of K-pop consumers affect their CCM listening intention and CCM loyalty?

- RQ 3. How does the CCM listening intention of K-pop consumers affect CCM loyalty?

2. Literature Review

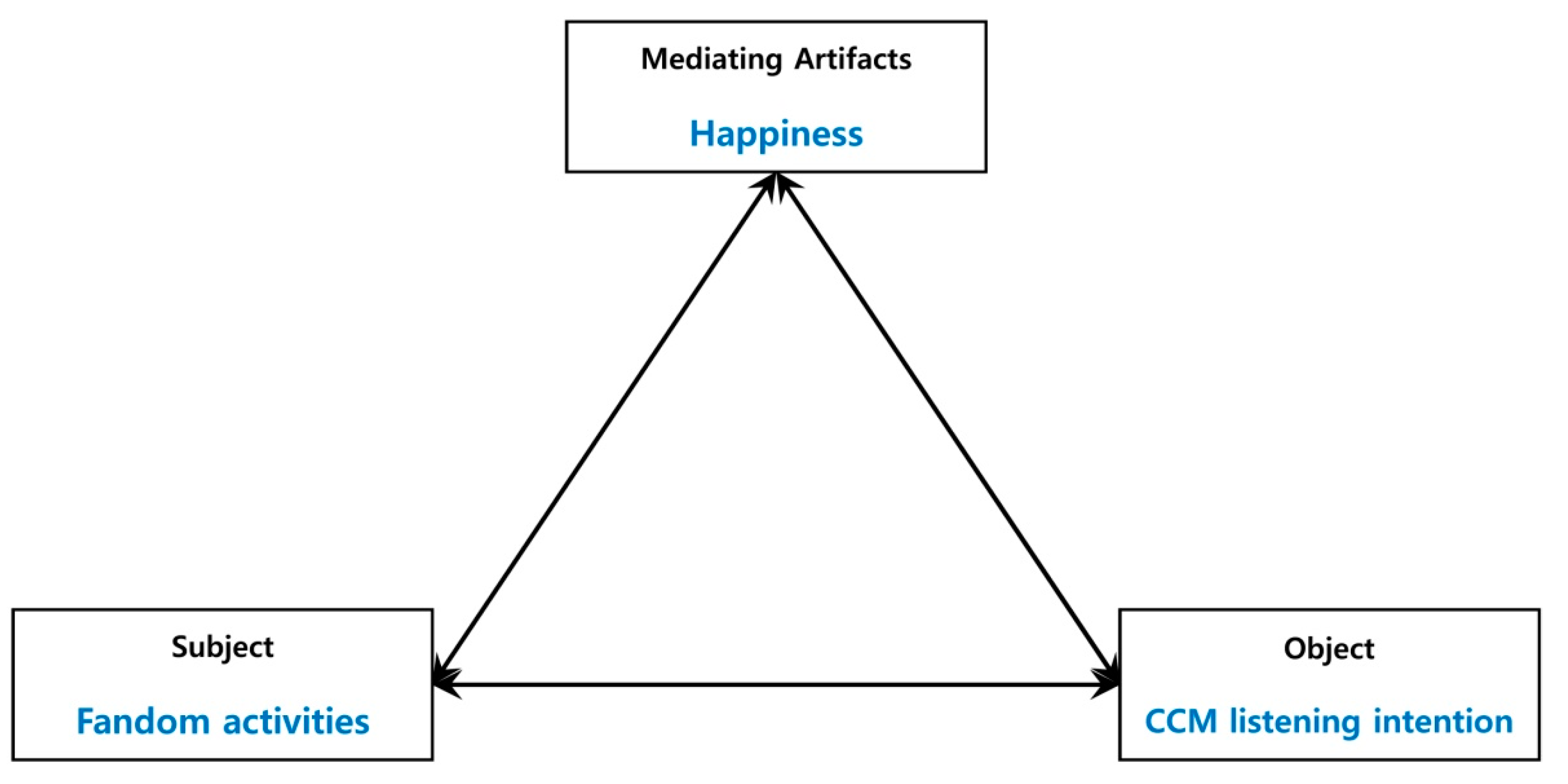

2.1. Base Theory

2.1.1. Activity Theory

2.1.2. Content Theory of Motivation

2.2. Concepts of Variables and Previous Studies

2.2.1. Fandom Activities and Happiness

2.2.2. Fandom Activities and CCM Listening Intention

2.2.3. Happiness and CCM Listening Intention, and Loyalty

3. Methods

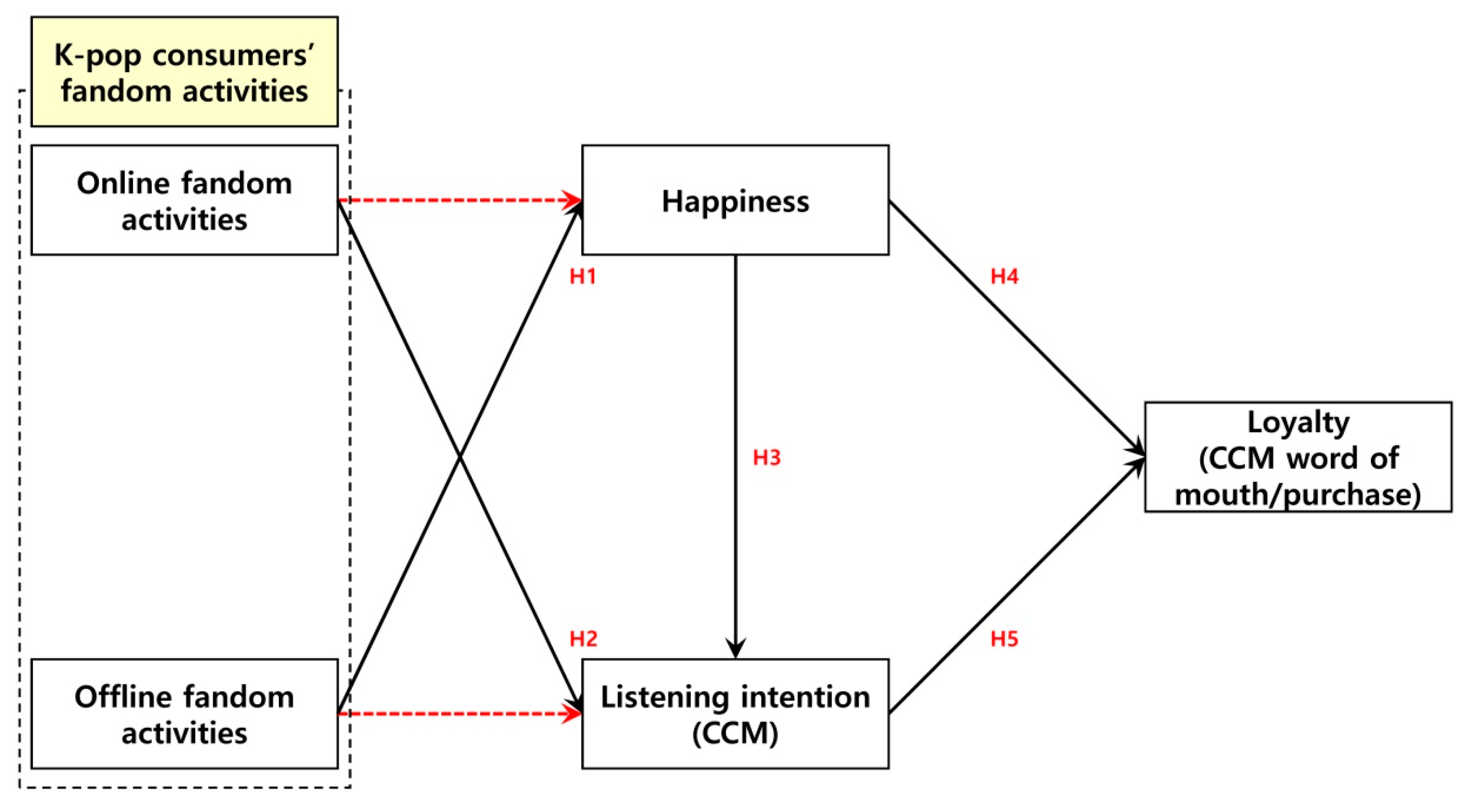

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Variable Measurement

3.3. Survey Respondents

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity

4.2. Correlation Analysis

4.3. Hypothesis Tests

4.4. Mediated Effect Test

5. Discussion

Summary of Results

6. Conclusions

6.1. Implications

6.1.1. Theoretical Implications

6.1.2. Practical Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Research Direction

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, J.H.; Jung, M.H.; Choi, H.J. Popular culture influences on national image and tourism behavioural intention: An exploratory study. J. Psychol. Afr. 2021, 31, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jung, S.H.; Roh, J.S.; Choi, H.J. Success factors and sustainability of the K-Pop Industry: A structural equation model and fuzzy set analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, K.J.; Park, B.T.; Choi, H.J. The Phenomenon and Development of K-Pop: The relationship between success factors of K-Pop and the national image, social network service citizenship behavior, and tourist behavioral intention. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H.E.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Jung, J.E.; Choi, H.J. Korean dance performance influences on prospective tourist cultural products consumption and behaviour intention. J. Psychol. Afr. 2019, 29, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Kim, J.H. Brand loyalty and the Bangtan Sonyeondan (BTS) Korean dance: Global viewers’ perceptions. J. Psychol. Afr. 2020, 30, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanozia, R.; Ganghariya, G. More than K-Pop fans: BTS fandom and activism amid COVID-19 outbreak. Media Asia 2021, 48, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y. The interweaving of network nationalism and transnational cultural consumption: The role conflict of K-Pop fans. Asian J. Commun. 2024, 34, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Pham, B.; Ferrara, E. Parasocial diffusion: K-Pop fandoms help drive COVID-19 public health messaging on social media. Online Soc. Netw. Media 2023, 37–38, 100267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Kim, J.; Yang, M.; Park, E.; Ko, M.; Lee, M.; Han, J. Behind the scenes of K-Pop fandom: Unveiling K-Pop fandom collaboration network. Qual. Quant. 2022, 56, 1481–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King-O’Riain, R.C. “They were having so much fun, so genuinely...:” K-Pop fan online affect and corroborated authenticity. New Media Soc. 2021, 23, 2820–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M. K-Pop fan labor and an alternative creative industry: A case study of GOT7 Chinese fans. Glob. Media China 2020, 5, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffan, D.A. Positive psychosocial outcomes and fanship in K-Pop fans: A social identity theory perspective. Psychol. Rep. 2021, 124, 2272–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Jenol, N.A.; Ahmad Pazil, N.H. “I found my talent after I become a K-pop fan”: K-Pop participatory culture unleashing talents among Malaysian youth. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 2062914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Foundation. Global Hallyu Status 2022; Korea Foundation: Seogwipo, Republic of Korea, 2022; pp. 1–207. [Google Scholar]

- Cavicchi, D. Fandom before “fan” shaping the history of enthusiastic audiences. Recept. Texts Readers Audiences Hist. 2014, 6, 52–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cavicchi, D. Foundational Discourses of Fandom. A Companion to Media Fandom and Fan Studies; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Crome, A. Reconsidering religion and fandom: Christian fan works in my little pony fandom. Cult. Relig. 2014, 15, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crome, A. Religion and the pathologization of fandom: Religion, reason, and controversy in my little pony fandom. J. Relig. Popul. Cult. 2015, 27, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M.A. Fandom as religion: A social-scientific assessment. J. Fandom Stud. 2021, 9, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löbert, A. Fandom as a religious form: On the reception of pop music by Cliff Richard fans in Liverpool. Pop. Mus. 2012, 31, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingalls, M.M. Style matters: Contemporary worship music and the meaning of popular musical borrowings. Liturgy 2017, 32, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenbaum, J. The neoliberalization of contemporary Christian Music’s New Social Gospel. Geoforum 2013, 44, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T. Music, Branding and Consumer Culture in Church: Hillsong in Focus; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wilder, C.; Rehwaldt, J. What makes music religious?: Contemporary Christian music and secularization. In Understanding Religion and Popular Culture; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Lie, J. K-Pop: Popular Music, Cultural Amnesia, and Economic Innovation in South Korea; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, H.Y. A characteristics comparison study of K-CCM and K-Pop. Doctoral Dissertation, Onseok Universit Graduate, 2020.

- Bakhurst, D. Reflections on activity theory. Educ. Rev. 2009, 61, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzman, L. What kind of theory is activity theory? Introduction. Theor. Psychol. 2006, 16, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, I. Contemporary Christian music and contemporary worship music. In The Routledge International Handbook of Sociology and Christianity; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 242–253. [Google Scholar]

- Fuschillo, G. Beyond the market: The societal influence of fandoms. In Consumer Culture Theory; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2016; pp. 169–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spracklen, K. “This Side of Paradise”: The Role of Online Fandom in the Construction of Leisure, Well-Being and the Lifeworld. Leisure, Health and Well-Being: A Holistic Approach; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, G. The role of dialogue in activity theory. Mind Cult. Act. 2002, 9, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, V.W.K. Thirty years of contemporary Christian Music in Hong Kong: Interactions and crossover acts between a religious music scene and the pop music scene. J. Creat. Commun. 2013, 8, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S. K-Pop Fandom in veil: Religious reception and adaptation to popular culture. J. Indones. Islam 2019, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, W.; Jin, D.Y.; Han, B. Transcultural fandom of the Korean wave in Latin America: Through the lens of cultural intimacy and affinity space. Media Cult. Soc. 2019, 41, 604–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedny, G.Z.; Karwowski, W. Activity theory as a basis for the study of work. Ergonomics 2004, 47, 134–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, W.M. Activity theory and education: An introduction. Mind Cult. Act. 2004, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.; Song, J.E. The Influences of K-Pop Fandom on Increasing Cultural Contact. Korean Assoc. Reg. Sociol. 2017, 18, 29–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wijaya Mulya, T. Faith and fandom: Young Indonesian Muslims negotiating K-Pop and Islam. Contemp. Islam 2021, 15, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K. Transnational fandom in the making: K-Pop fans in Vancouver. Int. Commun. Gaz. 2019, 81, 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, C.; Patwardhan, M.; Singh, R.K. A Literature review on motivation. Glob. Bus. Perspect. 2013, 1, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquah, A.; Nsiah, T.K.; Antie, E.N.A.; Otoo, B. Literature review on theories of motivation. EPRA Int. J. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2021, 9, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, D.C.; Atkinson, J.W.; Clark, R.A.; Lowell, E.L. Toward a theory of motivation. In The Achievement Motive; McClelland, D.C., Atkinson, J.W., Clark, R.A., Lowell, E.L., Eds.; Appleton-Century-Crofts: New York, NY, USA, 1953; pp. 6–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, A.L. Transnational identities and feeling in fandom: Place and embodiment in K-Pop fan reaction videos. Commun. Cult. Crit. 2018, 11, 548–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, W.C. Self-actualization myths: What did Maslow really say? J. Humanist. Psychol. 2024, 64, 743–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krems, J.A.; Kenrick, D.T.; Neel, R. Individual Perceptions of Self-Actualization: What Functional Motives Are Linked to Fulfilling One’s Full Potential? Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 43, 1337–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderman, E.M. Achievement motivation theory: Balancing precision and utility. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S. “Respectfully, pls ask someone else”: Pride and shame in international K-Pop fandom. In Mobile Communication in Asian Society and Culture; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 206–219. [Google Scholar]

- Ham, M.; Lee, S.W. Factors influencing viewing behavior in live streaming: An interview-based survey of music fans. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2020, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobur, A.; Darmawan, F.; Kusumalestari, R.R.; Listiani, E.; Ahmadi, D.; Albana, M.A. The meaning of K-Pop and self-concept transformation of K-Pop fans in Bandung. Mimbar J. Sos. Pembang. 2018, 34, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfving-Hwang, J. K-Pop Idols, Artificial Beauty and Affective Fan Relationships in South Korea. Routledge Handbook of Celebrity Studies; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 190–201. [Google Scholar]

- Duffett, M. Understanding Fandom: An Introduction to the Study of Media Fan Culture; Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, S.; Shim, D. Social distribution: K-Pop fan practices in Indonesia and the “Gangnam Style” phenomenon. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 2014, 17, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Liew, K.K. Analog Hallyu: Historicizing K-Pop formations in China. Glob. Media China 2019, 4, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aritenang, A.F.; Drianda, R.P.; Kesuma, M.; Ayu, N. The Korean wave during the coronavirus pandemic: An analysis of social media activities in Indonesia. World Leis. J. 2023, 66, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; SaRuLa, S.; Hwang, H. A comparative study of Korean and Chinese BTS female fandom: The effect of fandom activity on life satisfaction. J. Internet Comput. Serv. 2020, 21, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, C. K-Pop Dance: Fandoming Yourself on Social Media; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, I.; McAdams, D.P.; Little, B.R. Personal projects, life stories, and happiness: On being true to traits. J. Res. Pers. 2006, 40, 551–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Knobe, J.; Dunham, Y. Happiness is from the soul: The nature and origins of our happiness concept. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2021, 150, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, Z.; Haidar, S. Online community development through social interaction—K-Pop Stan Twitter as a community of practice. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 31, 733–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzchakov, G.; DeMarree, K.G.; Kluger, A.N.; Turjeman-Levi, Y. The listener sets the tone: High-quality listening increases attitude clarity and behavior-intention consequences. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 44, 762–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, K.J.; Boer, D.; Keller, J.W.; Voelpel, S. Is my boss really listening to me? The impact of perceived supervisor listening on emotional exhaustion, turnover intention, and organizational citizenship behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S. Tuning in sacred: Youth culture and contemporary Christian music. Int. Rev. Aesthet. Sociol. Music 2016, 47, 315–342. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.H. The Appropriation of popular culture: A sensational way of practicing evangelism of Korean Churches. Religions 2019, 10, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Kim, S.; Wong, A.K.F. Music-induced tourism: Korean Pop (K-Pop) music consumption values and their consequences. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 30, 100824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Lee, D.; Han, N.G.; Song, M. Exploring characteristics of video consuming behaviour in different social media using K-Pop videos. J. Inf. Sci. 2014, 40, 806–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H. The Korean Church’s view of popular culture. Theol. Minist. 2023, 59, 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.B. A study on the emerging Korean CCM in 1970∼1980s. Korean. J. Broadcast. Telecommun. Stud. 2016, 30, 157–187. Available online: http://www.riss.kr/link?id=A102103038 (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Choi, S.H. K-Pop and modern ministry: As viewed through the case of BTS. ACTSTJ 2022, 51, 178–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbaix, M.; Korchia, M. Individual celebration of pop music icons: A study of music fans relationships with their object of fandom and associated practices. J. Con. Behav. 2019, 18, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrick, N. Double authenticity: Celebrity, consumption, and the Christian worship music industry. Hymn 2018, 69, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.S.; Kim, J.H. Performing arts and sustainable consumption: Influences of consumer perceived value on ballet performance audience loyalty. J. Psychol. Afr. 2021, 31, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.H.; Jung, S.H.; Choi, H.J.; Kim, J. Antecedent factors that affect restaurant brand trust and brand loyalty: Focusing on US and Korean consumers. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2021, 30, 990–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgihan, A.; Madanoglu, M.; Ricci, P. Service attributes as drivers of behavioral loyalty in Casinos: The mediating effect of attitudinal loyalty. J. Retail. Con. Serv. 2016, 31, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, J. Factors that influence manufacturer and store brand behavioral loyalty. J. Retail. Con. Serv. 2022, 68, 103020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Yusta, A.; Martínez-Ruiz, M.P.; Pérez-Villarreal, H.H. Studying the impact of food values, subjective norm and brand love on behavioral loyalty. J. Retail. Con. Serv. 2022, 65, 102885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, D.; Han, H. Influence of environmental stimuli on hotel customer emotional loyalty response: Testing the moderating effect of the big five personality factors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 44, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Paço, A.; Kautish, P. The impact of eco-innovation on green buying behaviour: The moderating effect of emotional loyalty and generation. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2022, 33, 1026–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskinen, C.A.L.; Lindström, U.Å. An Envisioning About the Caring in Listening. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2015, 29, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamberti, P.M. Listening, Phronein, and the First Principle of Happiness. Thinking, Childhood, and Time: Contemporary Perspectives on the Politics of Education; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2020; pp. 75–228. [Google Scholar]

- Reybrouck, M.; Eerola, T. Musical enjoyment and reward: From hedonic pleasure to Eudaimonic listening. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, K.J.; Boer, D.; Voelpel, S.C. From listening to leading: Toward an understanding of supervisor listening within the framework of leader-member exchange theory. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2017, 54, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Quaquebeke, N.; Felps, W. Respectful inquiry: A motivational account of leading through asking questions and listening. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2018, 43, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanier, C.D., Jr.; Rader, C.S.; Fowler, A.R., III. Ambiguity and fandom: The (meaningless) consumption and production of popular culture. In Consumer Culture Theory; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2015; pp. 275–293. [Google Scholar]

- Parc, J.; Kim, S.D. The digital transformation of the Korean music industry and the global emergence of K-Pop. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibisono, N.; Arrasy, B.F.; Rafdinal, W. Predicting consumer behaviour toward digital K-Pop albums: An extended model of the theory of planned behaviour. J. Cult. Mark. Strategy 2022, 7, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adisak, S. The influence of customer expectations, customer loyalty, customer satisfaction and customer brand loyalty on customer purchasing intentions: A case study of K-POP fans in Thailand. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2022, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, E.M.; Kim, S.H.; Jeun, S.Y.; Jin, S.M.; Chung, I.J. The effect of fandom activity participation on adolescent school adjustment. Soc. Sci. Res. 2012, 28, 421–446. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, S.B. The analysis on the determinants of happiness in Korea. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 41, 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.Y. The effect of K-POP characteristics on the liking of Korean wave content, the intention of listening and the purchase intention of Korean products: Targeting Chinese consumers. J. Digit. Converg. 2017, 15, 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.T.; Kim, J.H. World culture festivals: Their perceived effect on and value to domestic and international tourism. J. Psychol. Afr. 2016, 26, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.H.; Kim, J.H.; Cho, H.N.; Lee, H.W.; Choi, H.J. Brand Personality of Korean Dance and Sustainable Behavioral Intention of Global Consumers in Four Countries: Focusing on the Technological Acceptance Model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jung, S.H.; Ahn, J.C.; Kim, B.S.; Choi, H.J. Social networking sites self-image antecedents of social networking site addiction. J. Psychol. Afr. 2020, 30, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, G.J.; Choi, H.J.; Seok, B.I.; Lee, N.H. Effects of social network services (SNS) Subjective norms on SNS addiction. J. Psychol. Afr. 2019, 29, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.H. Does workplace spirituality increase self-esteem in female professional dancers? The mediating effect of positive psychological capital and team trust. Religions 2023, 14, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amazon Ads. Digging into Trends: Global Insights into Fandom Culture and Brand Engagement. Available online: https://advertising.amazon.com/ko-kr/library/guides/global-research-on-fans-and-fan-engagement (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Fuhr, M. Globalization and Popular Music in South Korea: Sounding Out K-Pop; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Choe, H.J. The music listeners experience of listening to music changed by the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2021, 21, 281–293. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.Y.; Park, D.Y. Development and application of leisure happiness index in Koreans. Leis. Stud. 2014, 12, 149–173. [Google Scholar]

- Punyatoya, A. Emerging digital planetarities: The YouTube reaction video and affective fandom. In Affective World-Making; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 114–126. [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar, B.; Jaggi, R. Content consumption patterns of Korean pop fans in India. Cardiometry 2023, 25, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, C.; Lee, J. K-Pop TikTok: TikTok’s expansion into South Korea, TikTok stage, and platformed glocalization. Media Int. Aust. 2023, 188, 86–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, U.; Khan, M. K-Pop fans practices: Content consumption to participatory approach. Glob. Digit. Print Media Rev. 2023, VI, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Chang, W.J. A study on Chinese K-Pop fandom from the perspective of the audience and consumers. J. Korea Entertainment Ind. Assoc. 2021, 15, 51–64. Available online: http://www.riss.kr/link?id=A107400930 (accessed on 15 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.C. The effect of BTS preference on fandom star & fan community identification and purchase intention-focused on Korean and Southeast Asian. J. Korea Entertain. Ind. Assoc. 2020, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Operational Definition | Measurement Item | Researcher |

|---|---|---|---|

| Online fandom activities | Favorite K-pop singer—Degree of online fandom activities (passion/initiative) | 1. Favorite K-pop singer—I visit their homepage (including SNS). | An et al. [88] |

| 2. Favorite K-pop singer—I join fan club(s) or fan café(s). | |||

| 3. Favorite K-pop singer—I write email(s) or fan letter(s). | |||

| 4. Favorite K-pop singer—I comment on portals or articles. | |||

| 5. Favorite K-pop singer—I upload photos/videos online. | |||

| Offline fandom activities | Favorite K-pop singer—Degree of offline fandom activities (passion/initiative) | 1. Favorite K-pop singer—I attend fan meeting(s). | An et al. [88] |

| 2. Favorite K-pop singer—I attend fan sign event(s). | |||

| 3. Favorite K-pop singer—I go to a broadcasting station (to watch them). | |||

| 4. Favorite K-pop singer—I go to concert(s). | |||

| 5. Favorite K-pop singer—I go to music festival(s). | |||

| Happiness | Degree of satisfaction, enjoyment, and sense of reward in daily life | 1. Last 6 months—I am happy with my family life in general. | Shin [89] |

| 2. Last 6 months—I am happy with the household income in general. | |||

| 3. Last 6 months—I am happy with my relationships in general. | |||

| 4. Last 6 months—I am happy with my health in general. | |||

| 5. Last 6 months—I am happy with my work/studies, etc. in general. | |||

| Listening intention (CCM) | Favorite K-pop singer—Degree of CCM listening intention (passion/initiative) | 1. Favorite K-pop singer CCM—I will definitely listen to it. | Yu [90] |

| 2. Favorite K-pop singer CCM—I will listen to it before listening to anything else. | |||

| 3. Favorite K-pop singer CCM—I will listen to it often. | |||

| 4. Favorite K-pop singer CCM—I will listen to it regularly. | |||

| 5. Favorite K-pop singer CCM—I will listen to it occasionally. | |||

| Loyalty (CCM word of mouth/purchase) | Favorite K-pop singer CCM goods (products)—Degree of word of mouth/purchase (passion/initiative) | 1. Favorite K-pop singer CCM products (merchandise)—I positively consider buying them. | Kwon et al. [73] Lee & Kim [5] Lee & Kim [91] |

| 2. Favorite K-pop singer CCM products (merchandise)—I buy them even if the price is high. | |||

| 3. Favorite K-pop singer CCM products (merchandise)—I buy them whether they are sold online or offline. | |||

| 4. Favorite K-pop singer CCM products (merchandise)—I strongly recommend them. | |||

| 5. Favorite K-pop singer CCM products (merchandise)—I talk about the purchase favorably. |

| Item | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 165 | 49.8 |

| Female | 166 | 50.2 | |

| Age | 20 s | 86 | 26.0 |

| 30 s | 96 | 29.0 | |

| 40 s | 75 | 22.7 | |

| 50 s | 74 | 22.4 | |

| Education | High school graduate | 163 | 49.2 |

| Junior college graduate | 34 | 10.3 | |

| College graduate | 107 | 32.3 | |

| Graduate school graduate | 27 | 8.2 | |

| Monthly income (Mean) | Under $1000 | 60 | 18.1 |

| $1000–$2000 | 95 | 28.7 | |

| $2001–$3000 | 46 | 13.9 | |

| $3001–$4000 | 44 | 13.3 | |

| $4001–$5000 | 27 | 8.2 | |

| $5000 over | 59 | 17.8 | |

| Nationality | The U.S. | 165 | 49.8 |

| The UK | 166 | 50.2 | |

| Variable | Item | Convergent Validity | Cronbach’s Alpha | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outer Loadings | Composite Reliability | AVE | |||

| Online fandom activities | Online1 | 0.902 | 0.950 | 0.791 | 0.934 |

| Online2 | 0.922 | ||||

| Online3 | 0.869 | ||||

| Online4 | 0.890 | ||||

| Online5 | 0.862 | ||||

| Offline fandom activities | Offline1 | 0.890 | 0.956 | 0.811 | 0.942 |

| Offline2 | 0.943 | ||||

| Offline3 | 0.896 | ||||

| Offline4 | 0.881 | ||||

| Offline5 | 0.893 | ||||

| Happiness | Happiness1 | 0.818 | 0.930 | 0.727 | 0.906 |

| Happiness2 | 0.848 | ||||

| Happiness3 | 0.866 | ||||

| Happiness4 | 0.852 | ||||

| Happiness5 | 0.879 | ||||

| Listening intention (CCM) | Listening intention1 | 0.900 | 0.946 | 0.779 | 0.928 |

| Listening intention2 | 0.917 | ||||

| Listening intention3 | 0.935 | ||||

| Listening intention4 | 0.873 | ||||

| Listening intention5 | 0.778 | ||||

| Loyalty (CCM word of mouth/purchase) | Loyalty1 | 0.911 | 0.964 | 0.841 | 0.953 |

| Loyalty2 | 0.901 | ||||

| Loyalty3 | 0.926 | ||||

| Loyalty4 | 0.916 | ||||

| Loyalty5 | 0.930 | ||||

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Online fandom activities | 0.889 | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | Offline fandom activities | 0.840 | 0.901 | - | - | - |

| 3 | Happiness | 0.387 | 0.465 | 0.853 | - | - |

| 4 | Listening intention (CCM) | 0.805 | 0.724 | 0.496 | 0.882 | - |

| 5 | Loyalty (CCM word of mouth/purchase) | 0.765 | 0.746 | 0.507 | 0.848 | 0.917 |

| Hypothesis Path | β | Sample Mean | Standard Deviation | t | p | Result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Online fandom activities | → | Happiness | −0.011 | 0.002 | 0.129 | 0.083 | 0.934 | Not supported |

| H1b | Offline fandom activities | → | Happiness | 0.474 | 0.460 | 0.121 | 3.929 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2a | Online fandom activities | → | Listening intention | 0.672 | 0.678 | 0.082 | 8.152 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2b | Offline fandom activities | → | Listening intention | 0.063 | 0.055 | 0.089 | 0.704 | 0.482 | Not supported |

| H3 | Happiness | → | Listening intention | 0.207 | 0.209 | 0.052 | 4.013 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4 | Happiness | → | Loyalty | 0.094 | 0.093 | 0.030 | 3.148 | 0.002 | Supported |

| H5 | Listening intention | → | Loyalty | 0.832 | 0.831 | 0.033 | 25.480 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Path | β | Sample Mean | Standard Deviation | t | p | Mediated Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Online fandom activities → happiness → CCM listening intention → CCM loyalty | −0.002 | 0.000 | 0.022 | 0.082 | 0.934 | No |

| 2 | Offline fandom activities → happiness → CCM listening intention → CCM loyalty | 0.082 | 0.080 | 0.030 | 2.682 | 0.008 | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, H.-j. Do K-Pop Consumers’ Fandom Activities Affect Their Happiness, Listening Intention, and Loyalty? Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1136. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121136

Choi H-j. Do K-Pop Consumers’ Fandom Activities Affect Their Happiness, Listening Intention, and Loyalty? Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(12):1136. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121136

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Hyun-ju. 2024. "Do K-Pop Consumers’ Fandom Activities Affect Their Happiness, Listening Intention, and Loyalty?" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 12: 1136. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121136

APA StyleChoi, H.-j. (2024). Do K-Pop Consumers’ Fandom Activities Affect Their Happiness, Listening Intention, and Loyalty? Behavioral Sciences, 14(12), 1136. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121136