The Empire of Affectivity: Qualitative Evidence of the Subjective Orgasm Experience

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Type of Study

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Prototypical Analysis

3.2. Frequency Analysis

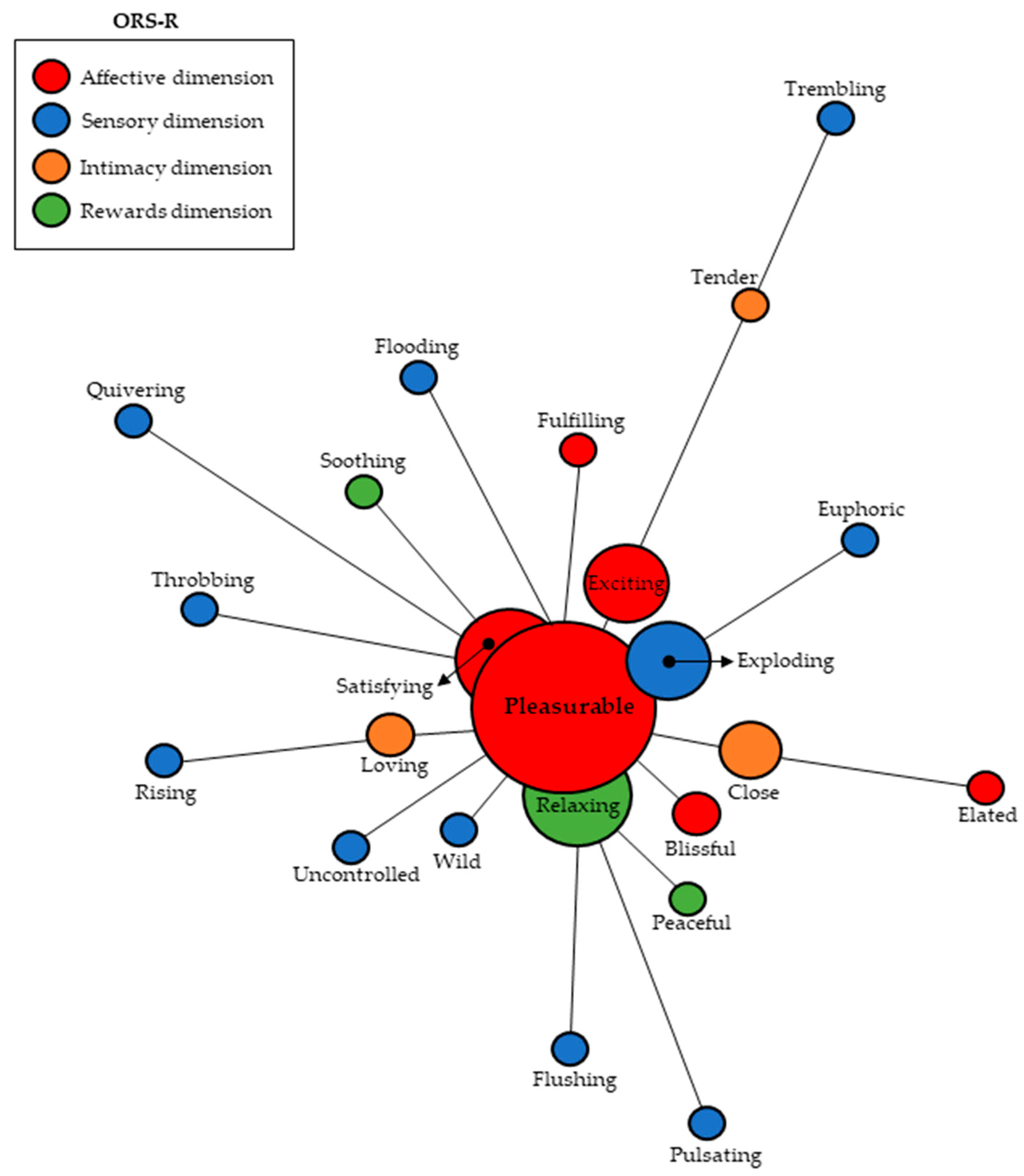

3.3. Similitude Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schiavi, R.C.; Segraves, R.T. The biology of sexual function. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 1995, 18, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meston, C.M.; Hull, E.; Levin, R.J.; Sipski, M. Disorders of orgasm in women. J. Sex. Med. 2004, 1, 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bancroft, J.; Loftus, J.; Long, J.S. Distress about sex: A national survey of women in heterosexual relationships. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2003, 32, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, J.S.; Carey, M.P. Prevalence of sexual dysfunctions: Results from a decade of research. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2001, 30, 177–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, L.D.; Kremer, E.C.; Brown, J. The incidental orgasm: The presence of clitoral knowledge and the absence of orgasm for women. Women Health 2005, 42, 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos-Romero, A.I.; Sierra, J.C. Factors associated with subjective orgasm experience in heterosexual relationships. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2020, 46, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcos-Romero, A.I.; Sierra, J.C. How do heterosexual men and women rate their orgasms in a relational context? Int. J. Impot. Res. 2023, 35, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mah, K.; Binik, Y.M. The nature of human orgasm: A critical review of major trends. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 21, 823–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangas, P.; Sierra, J.C.; Granados, R. Effects of subjective orgasm experience in sexual satisfaction: A dyadic analysis in same-sex Hispanic couples. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-García, L.E.; Gómez-Berrocal, C.; Sierra, J.C. Evaluating the subjective orgasm experience through sexual context, gender, and sexual orientation. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2023, 52, 1479–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panzeri, M.; Mauro, D.; Ronconi, L.; Arcos-Romero, A.I. Development of the Italian version of the Orgasmic Perception Questionnaire (OPQ). PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sierra, J.C.; Muñoz-García, L.E.; Mangas, P. And how do LGB adults rate their orgasms in a relational context? J. Sex. Med. 2024, qdad170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, J.M. The psychobiology of sexual experience. In The Psychobiology of Consciousness; Davidson, J.M., Davidson, R.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1980; pp. 271–332. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, J.E. A factor analytic study of the physical and affective dimensions of peak of female sexual response in partner-related sexual activity. Diss. Abstr. Int. Sect. A Humanit. Soc. Sci. 1981, 42, 1967–1968. [Google Scholar]

- Arcos-Romero, A.I.; Moyano, N.; Sierra, J.C. Psychometric properties of the Orgasm Rating Scale in context of sexual relationship in a Spanish sample. J. Sex. Med. 2018, 15, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, K.; Binik, Y.M. The Orgasm Rating Scale. In Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures, 4th ed.; Milhausen, R.R., Sakaluk, J.K., Fisher, T.D., Davis, C.M., Yarber, W.L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 503–507. [Google Scholar]

- Mah, K.; Binik, Y.M. Do all orgasms feel alike? Evaluating a two-dimensional model of the orgasm experience across gender and sexual context. J. Sex Res. 2002, 39, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubray, S.; Gérard, M.; Beaulieu-Prévost, D.; Courtois, F. Validation of a self-report questionnaire assessing the bodily and physiological sensations of orgasm. J. Sex. Med. 2017, 14, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limoncin, E.; Lotti, F.; Rossi, M.; Maseroli, E.; Gravina, G.L.; Ciocca, G.; Mollaioli, D.; Di Sante, S.; Maggi, M.; Lenzi, A.; et al. The impact of premature ejaculation on the subjective perception of orgasmic intensity: Validation and standardisation of the ‘Orgasmometer’. Andrology 2016, 4, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollaioli, D.; Di Sante, S.; Limoncin, E.; Ciocca, G.; Gravina, G.L.; Maseroli, E.; Fanni, E.; Vignozzi, L.; Maggi, M.; Lenzi, A.; et al. Validation of a Visual Analogue Scale to measure the subjective perception of orgasmic intensity in females: The Orgasmometer-F. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, S.; Klapilova, K.; Krejčová, L. More frequent vaginal orgasm is associated with experiencing greater excitement from deep vaginal stimulation. J. Sex. Med. 2013, 10, 1730–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangas, P.; Granados, R.; Cervilla, O.; Sierra, J.C. Validation of the Orgasm Rating Scale in context of sexual relationships of gay and lesbian adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollaioli, D.; Sansone, A.; Ciocca, G.; Limoncin, E.; Colonnello, E.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Jannini, E.A. Benefits of sexual activity on psychological, relational, and sexual health during the COVID-19 breakout. J. Sex. Med. 2021, 18, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prause, N.; Kuang, L.; Lee, P.; Miller, G. Clitorally stimulated orgasms are associated with better control of sexual desire, and not associated with depression or anxiety, compared with vaginally stimulated orgasms. J. Sex. Med. 2016, 13, 1676–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, R.; Brown, C.; Heiman, J.; Leiblum, S.; Meston, C.; Shabsigh, R.; Ferguson, D.; D’Agostino, R. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2000, 26, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sierra, J.C.; Ortiz, A.; Calvillo, C.; Arcos-Romero, A.I. Subjective Orgasm Experience in the context of solitary masturbation. Rev. Int. Androl. 2021, 19, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos-Romero, A.I.; Granados, R.; Sierra, J.C. Relationship between orgasm experience and sexual excitation: Validation of the Model of the Subjective Orgasm Experience. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2019, 31, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervilla, O.; Sierra, J.C.; Álvarez-Muelas, A.; Mangas, P.; Sánchez-Pérez, G.M.; Granados, R. Validation of the Multidimensional Model of the Subjective Orgasm Experience in the context of masturbation. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Salud. 2024, 15, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervilla, O.; Vallejo-Medina, P.; Gómez-Berrocal, C.; Torre-Vílchez, D.; Sierra, J.C. Validation of the Orgasm Rating Scale in the context of masturbation. Psicothema 2022, 34, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opperman, E.; Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Rogers, C. “It feels so good it almost hurts”: Young adults’ experiences of orgasm and sexual pleasure. J. Sex Res. 2014, 51, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergès, P. L’ évocation de l’argent: Une méthode pour la définition du noyau central d’une représentation. Bull. Psychol. 1992, 45, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kherabi, Y.; Vinchon, F.; Rolland, F.; Gouy, E.; Frajerman, A.; Truong, L.N.; Bodard, S.; Hadouiri, N. What do medical students and graduated physicians think about infectious disease specialists? Infect. Dis. Now. 2023, 53, 104783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes do Vale, S.; Maciel, R.H. The structure of students’ parents’ social representations of teachers. Trends Psychol. 2019, 27, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idoiaga, N.; Berasategi, N.; Eiguren, A.; Picaza, M. Exploring children’s social and emotional representations of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengzhen, L.; Lim, D.H.J.; Berezina, E.; Benjamin, J. Navigating love in a post-pandemic world: Understanding young adults’ views on short-and long-term romantic relationships. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2023, 53, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankis, J.; Flowers, P.; McDaid, L.; Bourne, A. Low levels of chemsex among men who have sex with men, but high levels of risk among men who engage in chemsex: Analysis of a cross-sectional online survey across four countries. Sex. Health 2018, 15, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wachelke, J.; Wolter, R. Critérios de construção e relato da análise prototípica para representações sociais. Psic. Teor. Pesq. 2011, 27, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, L.F.; Rocha, F.; dos Santos Dias, M.M.; dos Santos Pires, A.C.; Vidigal, M.C.T.R. Comfort plant-based food: What do consumers want? A focus group study with different consumers group. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2023, 34, 100810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, B.V.; Justo, A.M. IRAMUTEQ: Um software gratuito para análise de dados textuais. Temas Psicol. 2013, 21, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.A.R.; Wall, M.L.; Thuler, A.C.M.C.; Lowen, I.M.V.; Peres, A.M. The use of IRAMUTEQ software for data analysis in qualitative research. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2018, 52, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachelke, J.; Wolter, R.; Matos, F.R. Efeito do tamanho da amostra na análise de evocações para representações sociais. Liberabit 2016, 22, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomozzi, A.I.; de Rosa, A.S.; da Silva, M.L.B.; Gizzi, F.; de Sena Moraes, V. Social Representations of (Im) migrants in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil: A study of online news. Pap. Soc. Represent. 2023, 32, 3.1–3.33. [Google Scholar]

- Lamprea-Abril, N. Discursive configurations about the Francophone World and the French Language in Colombian Written Press. Ikala 2023, 28, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, B.V.; Justo, A.M. Tutorial Para uso do Software de Análise Textual IRAMUTEQ; Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina: Florianópolis, Brazil, 2016; Available online: http://iramuteq.org/documentation/fichiers/Tutorial%20IRaMuTeQ%20em%20portugues_17.03.2016.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Sousa, Y.S.O. O Uso do Software IRAMUTEQ: Fundamentos de Lexicometria para Pesquisas Qualitativas. Estud. Pesqui. Psicol. 2021, 21, 1541–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klant, L.M.; Santos, V.S. The use of the IRAMUTEQ software in content analysis—A comparative study between the ProfEPT course completion works and the program references. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e8210413786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensman, L. Two People Just Make It Better: The Psychological Differences between Partnered Orgasms and Solitary Orgasms. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland, D.L.; Sullivan, S.L.; Hevesi, K.; Hevesi, B. Orgasmic latency and related parameters in women during partnered and masturbatory sex. J. Sex. Med. 2018, 15, 1463–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbenick, D.; Fu, T.J.; Dodge, B.; Baldwin, A. 008 Female Pleasure and Orgasm: Results from a US Nationally Representative Survey. J. Sex. Med. 2016, 13, S242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallen, K.; Lloyd, E.A. Female sexual arousal: Genital anatomy and orgasm in intercourse. Horm. Behav. 2011, 59, 780–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin-Mathieu, G.; Berry, M.; Shtarkshall, R.A.; Amsel, R.; Binik, Y.M.; Gérard, M. Exploring male multiple orgasm in a large online sample: Refining our understanding. J. Sex. Med. 2021, 18, 1652–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerwenka, S.; Dekker, A.; Pietras, L.; Briken, P. Single and multiple orgasm experience among women in heterosexual partnerships. Results of the German health and sexuality survey (GeSiD). J. Sex. Med. 2021, 18, 2028–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gérard, M.; Berry, M.; Shtarkshall, R.A.; Amsel, R.; Binik, Y.M. Female multiple orgasm: An exploratory internet-based survey. J. Sex Res. 2021, 58, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A. Masturbation in the United States. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2007, 33, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnerus, M.; Price, J.; Gordon, D. Masturbation and partnered sex: Substitutes or complements? Arch. Sex. Behav. 2017, 46, 2111–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalheira, A.; Træen, B.; Stulhofer, A. Masturbation and pornography use among coupled heterosexual men with decreased sexual desire: How many roles of masturbation? J. Sex Marital Ther. 2015, 41, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gana, K.; Trouillet, R.; Martin, B.; Toffart, L. The relationship between boredom proneness and solitary sexual behaviors in adults. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2001, 29, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, T.; Chen, J.; Niu, Y. Masturbation is associated with psychopathological and reproduction health conditions: An online survey among campus male students. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2022, 37, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleuteri, S.; Alessi, F.; Petruccelli, F.; Saladino, V. The global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on individuals’ and couples’ sexuality. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 798260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driemeyer, W.; Janssen, E.; Wiltfang, J.; Elmerstig, E. Masturbation experiences of Swedish senior high school students: Gender differences and similarities. J. Sex Res. 2017, 54, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalheira, A.; Leal, I. Masturbation among women: Associated factors and sexual response in a Portuguese community sample. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2013, 39, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramson, P.R.; Perry, L.B.; Rothblatt, A.; Seeley, T.T.; Seeley, D.M. Negative attitudes toward masturbation and pelvic vasocongestion: A thermographic analysis. J. Res. Pers. 1981, 15, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real Academia Española. Available online: https://dle.rae.es/efusivo (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Pérez-Amorós, C.; Sierra, J.C.; Mangas, P. Subjective Orgasm Experience in Different-Sex and Same-Sex Couples: A Dyadic Approach; University of Granada: Granada, Spain, 2023; manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Matsick, J.L.; Conley, T.D.; Moors, A.C. The science of female orgasms: Pleasing female partners in casual and long-term relationships. In The Psychology of Love and Hate in Intimate Relationships; Aumer, K., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Burri, A.; Carvalheira, A. Masturbatory behavior in a population sample of German women. J. Sex. Med. 2019, 16, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahs, B. Coming to power: Women’s fake orgasms and best orgasm experiences illuminate the failures of (hetero) sex and the pleasures of connection. Cult. Health Sex. 2014, 16, 974–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, S.; Nichols, T.R.; Tanner, A.E.; Kuperberg, A.; Payton Foh, E. Relational and partner-specific factors influencing black heterosexual women’s initiation of sexual intercourse and orgasm frequency. Sex. Cult. 2021, 25, 503–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Range ≤ 2.88 | Range > 2.88 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Frequency | Central Core | First Periphery | ||||

| Evocations | f | Range | Evocations | f | Range | |

| Placentero/Pleasurable | 228 | 2.1 | Relajante/Relaxing | 72 | 3.4 | |

| Intenso/Intense | 195 | 1.9 | Agradable/Pleasant | 47 | 3.3 | |

| Satisfactorio/Satisfying | 61 | 2.8 | Divertido/Fun | 35 | 3.3 | |

| Excitante/Exciting | 49 | 2.8 | Íntimo/Close | 32 | 3.3 | |

| Liberador/Liberating | 42 | 2.8 | Deseado/Desired | 30 | 3.4 | |

| Explosivo/Exploding | 36 | 2.8 | Largo/Long | 30 | 3 | |

| ≥9.66 | Corto/Short | 26 | 2.3 | Bonito/Beautiful | 24 | 3.4 |

| Fuerte/Heavy | 20 | 2.5 | Bueno/Good | 24 | 3 | |

| Maravilloso/Blissful | 15 | 2.6 | Amoroso/Loving | 22 | 4.1 | |

| Pasional/Passionate | 15 | 2.7 | Rápido/Quick | 20 | 3.3 | |

| Suave/Soft | 11 | 2.3 | Feliz/Happy | 18 | 3.8 | |

| Éxtasis/Ecstasy | 11 | 1.8 | Gustoso/Tasty | 17 | 3.6 | |

| Increíble/Incredible | 10 | 2.7 | Húmedo/Wet | 15 | 3.3 | |

| Eléctrico/Electric | 10 | 2 | Caliente/Hot | 15 | 3.6 | |

| Average Frequency | Zone of Contrast | Second Periphery | ||||

| Evocations | f | Range | Evocations | f | Range | |

| Breve/Brief | 6 | 2.5 | Apasionado/Passionate | 9 | 3.8 | |

| Brutal/Brutal | 6 | 2.5 | Reconfortante/Soothing | 9 | 3.4 | |

| Rico/Delicious | 5 | 2 | Romántico/Romantic | 9 | 4.1 | |

| Complicidad/Complicity | 5 | 2 | Salvaje/Wild | 8 | 3 | |

| Completo/Complete | 5 | 2.6 | Tranquilizante/Peaceful | 8 | 3.6 | |

| Nuevo/New | 4 | 2.5 | Gratificante/Fulfilling | 8 | 3.4 | |

| <9.66 | Progresivo/Progressive | 4 | 2.5 | Morboso/Lustful | 8 | 3.6 |

| Pasión/Passion | 4 | 2 | Emocionante/Exciting | 7 | 3.4 | |

| Eufórico/Euphoric | 4 | 2.8 | Conexión/Connection | 7 | 3.4 | |

| Extático/Ecstatic | 3 | 2.3 | Profundo/Deep | 7 | 3.6 | |

| Caluroso/Warm | 3 | 2.7 | Cómplice/Complicit | 7 | 3.4 | |

| Animal/Animal | 2 | 2.5 | Seguro/Safe | 6 | 3 | |

| Saciante/Satiating | 2 | 2.5 | Estimulante/Stimulating | 6 | 4.3 | |

| Comunicación/Communication | 2 | 2.5 | Sensual/Sensual | 5 | 3.2 | |

| Range ≤ 2.87 | Range > 2.87 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Frequency | Central Core | First Periphery | ||||

| Evocations | f | Range | Evocations | f | Range | |

| Placentero/Pleasurable | 163 | 2.4 | Satisfactorio/Satisfying | 60 | 3.2 | |

| Intenso/Intense | 125 | 2 | Corto/Short | 41 | 3 | |

| Rápido/Quick | 114 | 2.3 | Liberador/Liberating | 39 | 2.9 | |

| Relajante/Relaxing | 103 | 2.8 | Agradable/Pleasant | 37 | 3 | |

| Íntimo/Close | 34 | 2.6 | Solitario/Solitary | 31 | 3.6 | |

| Tranquilizante/Peaceful | 25 | 2.8 | Bueno/Good | 21 | 3.1 | |

| ≥8.96 | Excitante/Exciting | 25 | 2.7 | Divertido/Fun | 19 | 3.3 |

| Rutinario/Routine | 18 | 2.6 | Fácil/Easy | 18 | 3.3 | |

| Desestresante/De-stressing | 18 | 2.6 | Caliente/Hot | 16 | 3.2 | |

| Necesario/Necessary | 16 | 2.4 | Aburrido/Boring | 15 | 3.1 | |

| Explosivo/Exploding | 16 | 1.9 | Gustoso/Tasty | 14 | 3.1 | |

| Largo/Long | 16 | 2.7 | Cómodo/Comfortable | 13 | 3.8 | |

| Breve/Brief | 15 | 2.4 | Fantasioso/Fanciful | 10 | 2.9 | |

| Deseado/Desired | 11 | 2.3 | Normal/Normal | 10 | 3.5 | |

| Average Frequency | Zone of Contrast | Second Periphery | ||||

| Evocations | f | Range | Evocations | f | Range | |

| Buscado/Wanted | 8 | 2.1 | Sucio/Dirty | 8 | 3.8 | |

| Alivio/Relief | 7 | 2.3 | Gratificante/Fulfilling | 8 | 3.9 | |

| Simple/Simple | 6 | 2.8 | Maravilloso/Blissful | 8 | 3 | |

| Práctico/Handy | 6 | 2.8 | Increíble/Incredible | 8 | 3.4 | |

| Duradero/Lasting | 5 | 2.5 | Mecánico/Mechanic | 8 | 3.2 | |

| Imaginación/Imagination | 5 | 2.4 | Húmedo/Wet | 7 | 3.3 | |

| <8.96 | Lento/Slow | 5 | 2 | Potente/Powerful | 7 | 3.7 |

| Incompleto/Incomplete | 4 | 2.8 | Frío/Cold | 7 | 3.3 | |

| Controlado/Controlled | 4 | 2.2 | Triste/Sad | 6 | 4.5 | |

| Cotidiano/Daily | 4 | 2.8 | Conocido/Known | 6 | 3.3 | |

| Espontáneo/Spontaneous | 4 | 2 | Cansado/Tired | 5 | 4.6 | |

| Palpitante/Pulsating | 3 | 2.7 | Repetitivo/Repetitive | 4 | 3.8 | |

| Ansioso/Anxious | 3 | 2.3 | Funcional/Functional | 4 | 3.5 | |

| Displacentero/Unpleasurable | 2 | 1.5 | Innecesario/Unnecessary | 4 | 4.8 | |

| ORS-R | ORS-M | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjectives | Frequency | % of Total | % of Rows | Rank | Rank | Frequency | % of Total | % of Rows | |

| A | Pleasurable (placentero) | 228 | 5.83 | 57.0 | 1 | 1 | 163 | 4.24 | 40.25 |

| R | Relaxing (relajante) | 72 | 1.84 | 18.0 | 2 | 2 | 103 | 2.68 | 25.75 |

| A | Satisfying (satisfactorio) | 61 | 1.56 | 15.25 | 3 | 3 | 60 | 1.56 | 15.0 |

| A | Exciting (excitante) | 49 | 1.25 | 12.25 | 4 | 6 | 25 | 0.65 | 6.25 |

| S | Exploding (explosivo) | 36 | 0.92 | 9.0 | 5 | 7 | 16 | 0.42 | 4.0 |

| I | Close (íntimo) | 32 | 0.82 | 8.0 | 6 | 4 | 34 | 0.88 | 8.5 |

| I | Loving (amoroso) | 22 | 0.56 | 5.5 | 7 | 16 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.25 |

| A | Blissful (maravilloso) | 15 | 0.38 | 3.75 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 0.21 | 2.0 |

| R | Soothing (reconfortante) | 9 | 0.23 | 2.25 | 9 | 11 | 5 | 0.13 | 1.25 |

| S | Wild (salvaje) | 8 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 10 | 17 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.25 |

| R | Peaceful (tranquilizante) | 8 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 11 | 5 | 25 | 0.65 | 6.25 |

| A | Fulfilling (gratificante) | 8 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 0.21 | 2.0 |

| S | Throbbing (vibrante) | 5 | 0.13 | 1.25 | 13 | 8 | 9 | 0.23 | 2.25 |

| S | Uncontrolled (incontrolable) | 4 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 14 | 19 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.25 |

| I | Tender (tierno) | 4 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 15 | - | - | - | - |

| S | Euphoric (eufórico) | 4 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 16 | 15 | 2 | 0.05 | 0.5 |

| S | Trembling (tembloroso) | 3 | 0.08 | 0.75 | 17 | 12 | 3 | 0.08 | 0.75 |

| S | Flooding (desbordante) | 2 | 0.05 | 0.5 | 18 | - | - | - | - |

| S | Flushing (sofocante) | 2 | 0.05 | 0.5 | 19 | 18 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.25 |

| A | Elated (gozoso) | 2 | 0.05 | 0.5 | 20 | 14 | 3 | 0.08 | 0.75 |

| S | Quivering (estremecedor) | 2 | 0.05 | 0.5 | 21 | 21 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.25 |

| S | Rising (creciente) | 1 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 22 | - | - | - | - |

| S | Pulsating (palpitante) | 1 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 23 | 13 | 3 | 0.08 | 0.75 |

| S | Shooting (desbocado) | - | - | - | - | 20 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.25 |

| S | Spreading (efusivo) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Dimensions | Frequency | % of Total | % of Rows | Σ | Σ | Frequency | % of Total | % of Rows | |

| Affective | 363 | 9.27 | 90.75 | 60.5 | 44.5 | 267 | 6.95 | 66.25 | |

| Sensory | 68 | 1.74 | 17 | 6.18 | 3.8 | 38 | 1.01 | 9.5 | |

| Intimacy | 58 | 1.48 | 14.5 | 19.33 | 17.5 | 35 | 0.91 | 8.75 | |

| Rewards | 89 | 2.27 | 22.25 | 29.67 | 44.33 | 133 | 3.46 | 33.25 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mangas, P.; da Silva Alves, M.E.; Fernandes de Araújo, L.; Sierra, J.C. The Empire of Affectivity: Qualitative Evidence of the Subjective Orgasm Experience. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030171

Mangas P, da Silva Alves ME, Fernandes de Araújo L, Sierra JC. The Empire of Affectivity: Qualitative Evidence of the Subjective Orgasm Experience. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(3):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030171

Chicago/Turabian StyleMangas, Pablo, Mateus Egilson da Silva Alves, Ludgleydson Fernandes de Araújo, and Juan Carlos Sierra. 2024. "The Empire of Affectivity: Qualitative Evidence of the Subjective Orgasm Experience" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 3: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030171

APA StyleMangas, P., da Silva Alves, M. E., Fernandes de Araújo, L., & Sierra, J. C. (2024). The Empire of Affectivity: Qualitative Evidence of the Subjective Orgasm Experience. Behavioral Sciences, 14(3), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030171

_Chan.jpg)