Enhancing Inclusive Teaching in China: Examining the Effects of Principal Transformational Leadership, Teachers’ Inclusive Role Identity, and Efficacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To what extent does principal transformational leadership influence teachers’ inclusive teaching behaviour?

- Do teachers’ inclusive role identity and efficacy independently mediate the effects of principal transformational leadership on teachers’ inclusive teaching behaviour?

- Do teachers’ inclusive role identity and efficacy sequentially mediate the effects of principal transformational leadership on teachers’ inclusive teaching behaviour?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Principal Transformational Leadership and Teachers’ Inclusive Teaching Behaviour

2.2. Teachers’ Inclusive Role Identity

2.3. Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practice

2.4. Sequential Mediation of Teachers’ Inclusive Role Identity and Efficacy for Inclusive Practice

2.5. The Hypothesised Model of Study

3. Research Context

4. Method

4.1. Participants and Procedures

4.2. Demographic Information

4.3. Measures

4.3.1. Principal Transformational Leadership

4.3.2. Teachers’ Inclusive Role Identity

4.3.3. Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practice

4.3.4. Teachers’ Inclusive Teaching Behaviour

4.3.5. Control Variables

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Correlation Analysis

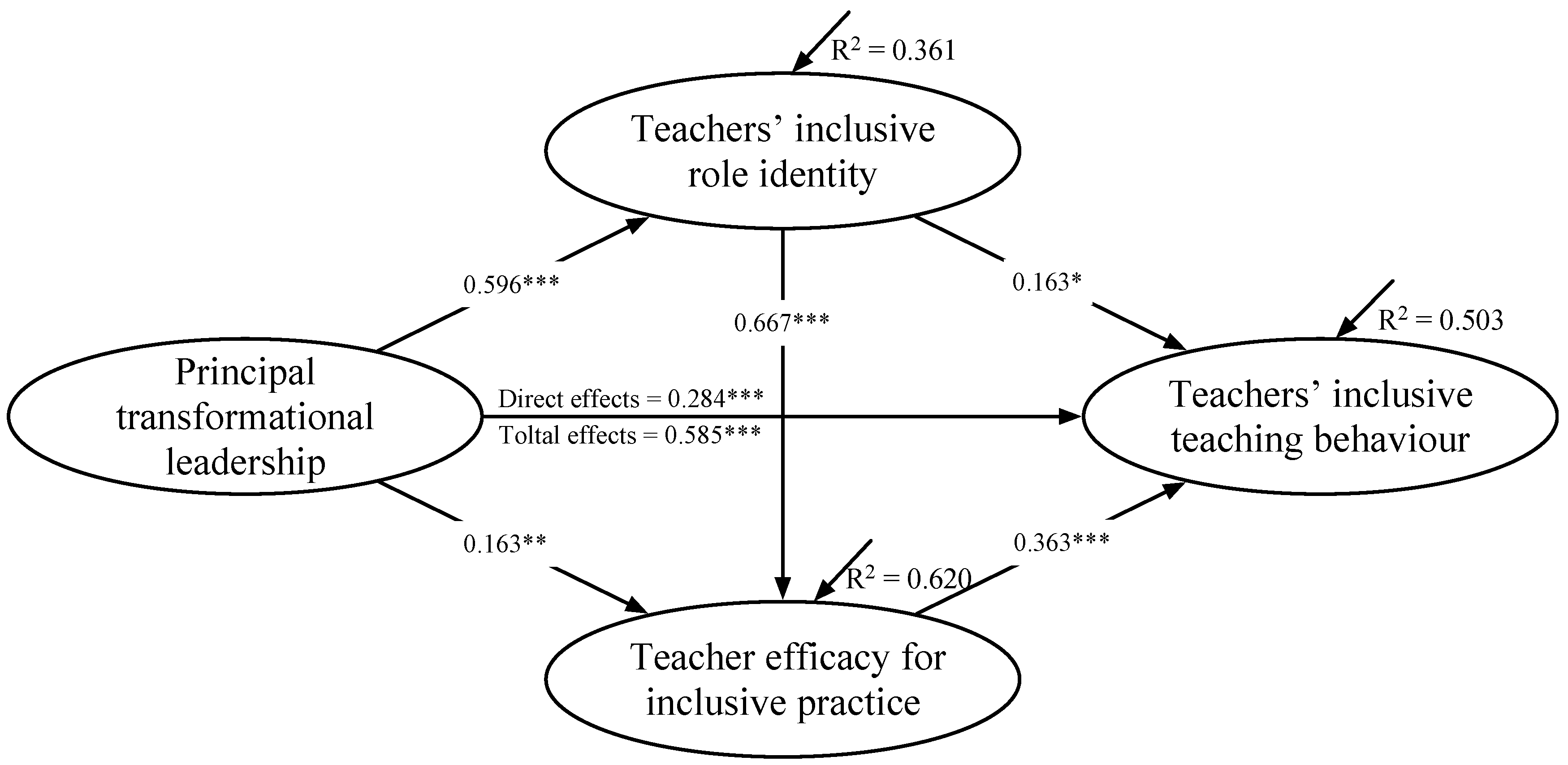

5.2. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM)

6. Discussion

7. Implications

8. Limitations

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000110753 (accessed on 7 June 1994).

- Subban, P.; Woodcock, S.; Sharma, U.; May, F. Student experiences of inclusive education in secondary schools: A systematic review of the literature. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022, 119, 103853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norwich, B.; Benham-Clarke, S.; Goei, S.L. Review of research literature about the use of lesson study and lesson study-related practices relevant to the field of special needs and inclusive education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2021, 36, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruggink, M.; Goei, S.L.; Koot, H.M. Teachers’ capacities to meet students’ additional support needs in mainstream primary education. Teach. Teach. 2016, 22, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Sharma, U.; Choi, H. Impact of teacher education on pre-service regular school teachers’ attitudes, intentions, concerns and self-efficacy about inclusive education in South Korea. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 86, 102901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moberg, S.; Muta, E.; Korenaga, K.; Kuorelahti, M.; Savolainen, H. Struggling for inclusive education in Japan and Finland: Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2020, 35, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black-Hawkins, K.; Florian, L. Classroom teachers’ craft knowledge of their inclusive practice. Teach. Teach. 2012, 18, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiandes, S. Evaluating the impact of differentiated instruction on literacy and reading in mixed ability classrooms: Quality and equity dimensions of education effectiveness. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2015, 45, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, S.; Sharma, U.; Hoffmann, L. How inclusive are the teaching practices of my German, Maths and English teachers?—Psychometric properties of a newly developed scale to assess personalisation and differentiation in teaching practices. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2022, 26, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, S.; Sharma, U.; Subban, P.; Hitches, E. Teacher self-efficacy and inclusive education practices: Rethinking teachers’ engagement with inclusive practices. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022, 117, 103802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molbaek, M. Inclusive teaching strategies—Dimensions and agendas. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2018, 22, 1048–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, E.; Sharma, U.; Subban, P. Factors influencing teacher self-efficacy for inclusive education: A systematic literature review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022, 117, 103800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U.; Sokal, L.; Wang, M.; Loreman, T. Measuring the use of inclusive practices among pre-service educators: A multi-national study. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 107, 103506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Marks Woolfson, L.; Durkin, K. School environment and mastery experience as predictors of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs towards inclusive teaching. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 24, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, W. The Effects of Principal Support on Teachers’ Professional Skills: The Mediating Role of School-Wide Inclusive Practices and Teacher Agency. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2021, 68, 773–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoonen, E.E.J.; Sleegers, P.J.C.; Oort, F.J.; Peetsma, T.T.D.; Geijsel, F.P. How to Improve Teaching Practices: The Role of Teacher Motivation, Organizational Factors, and Leadership Practices. Educ. Adm. Q. 2011, 47, 496–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.N.; Murphy, W.H.; Anderson, R.E. Transformational leadership effects on salespeople’s attitudes, striving, and performance. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 110, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K.; Jantzi, D. Transformational school leadership for large-scale reform: Effects on students, teachers, and their classroom practices. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2006, 17, 201–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-J.; Demerouti, E.; Le Blanc, P. Transformational leadership, adaptability, and job crafting: The moderating role of organizational identification. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 100, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Óskarsdóttir, E.; Donnelly, V.; Turner-Cmuchal, M.; Florian, L. Inclusive school leaders—Their role in raising the achievement of all learners. J. Educ. Adm. 2020, 58, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billingsley, B.; DeMatthews, D.; Connally, K.; McLeskey, J. Leadership for Effective Inclusive Schools: Considerations for Preparation and Reform. Australas. J. Spec. Incl. Educ. 2018, 42, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, P.J.; Reitzes, D.C. The Link between Identity and Role Performance. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1981, 44, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, P.J.; Stets, J.E. Identity Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X. Constructing the associations between creative role identity, creative self-efficacy, and teaching for creativity for primary and secondary teachers. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.Y.; Yin, H.B.; Wang, J.J. A case study of faculty perceptions of teaching support and teaching efficacy in China: Characteristics and relationships. High. Educ. 2018, 76, 519–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strachan, S.M.; Brawley, L.R.; Spink, K.S.; Sweet, S.N.; Perras, M.G.M. Self-regulatory efficacy’s role in the relationship between exercise identity and perceptions of and actual exercise behaviour. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 18, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navickaitė, J. The Expression of a Principal’s Transformational Leadership during the Organizational Change Process: A Case Study of Lithuanian General Education Schools. Probl. Educ. 21st Century 2013, 51, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, B.P. Transformational Leadership. In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance; Farazmand, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G.A. Leadership in Organizations, 9th ed.; Pearson: Landon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron, N.L.; McLeskey, J.; Redd, L. Setting the Direction: The Role of the Principal in Developing an Effective, Inclusive School. J. Spec. Educ. Leadersh. 2011, 24, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. How Does Principals’ Transformational Leadership Impact Students’ Modernity? A Multiple Mediating Model. Educ. Urban Soc. 2021, 53, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoraiki, M.; Ahmad, A.R.; Ateeq, A.A.; Naji, G.M.A.; Almaamari, Q.; Beshr, B.A.H. Impact of Teachers’ Commitment to the Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Sustainable Teaching Performance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Sun, J.P. The Nature and Effects of Transformational School Leadership: A Meta-Analytic Review of Unpublished Research. Educ. Adm. Q. 2012, 48, 387–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, L.J.; de Bruin, K.; Lassig, C.; Spandagou, I. A scoping review of 20 years of research on differentiation: Investigating conceptualisation, characteristics, and methods used. Rev. Educ. 2021, 9, 161–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, S.; Gumpel, T.P.; Koller, J.; Wiesenthal, V.; Weintraub, N. Can self-efficacy mediate between knowledge of policy, school support and teacher attitudes towards inclusive education? PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, S.; Resch, K.; Alnahdi, G. Inclusion does not solely apply to students with disabilities: Pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive schooling of all students. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, D.; Walton, E.; Osman, R. Constraints to the implementation of inclusive teaching: A cultural historical activity theory approach. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 25, 1508–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, G.J.; Simmons, J.L. Identities and Interactions: An Examination of Human Associations in Everyday Life, Rev. ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Petkus, E. The creative identity: Creative behavior from the symbolic interactionist perspective. J. Creat. Behav. 1996, 30, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, H.; Gimeno, J. Becoming a founder: How founder role identity affects entrepreneurial transitions and persistence in founding. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guntert, S.T.; Wehner, T. The impact of self-determined motivation on volunteer role identities: A cross-lagged panel study. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 78, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryker, S.; Burke, P.J. The past, present, and future of an identity theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 63, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J.E.; Burke, P.J. A sociological approach to self and identity. In Handbook of Self and Identity; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 128–152. [Google Scholar]

- Cast, A.D.; Burke, P.J. A theory of self-esteem. Soc. Forces 2002, 80, 1041–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, S.M.; Tierney, P.; Kung-McIntyre, K. Employee creativity in Taiwan: An application of role identity theory. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lee, J.C.-K.; Yang, X. What really counts? Investigating the effects of creative role identity and self-efficacy on teachers’ attitudes towards the implementation of teaching for creativity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 84, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.W.; Watt, H.M.G. Teacher Professional Identity and Career Motivation: A Lifespan Perspective. In Research on Teacher Identity: Mapping Challenges and Innovations; Schutz, P.A., Hong, J., Francis, D.C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeskey, J.; Waldron, N.L. Effective leadership makes schools truly inclusive. Phi Delta Kappan 2015, 96, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.J.; Xie, Z.L.; Wang, L.L.; Deng, M. A Qualitative Study of the Transformation of General Education Teachers to Inclusive Education Actors. J. Sch. Stud. 2022, 19, 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Tschannen-Moran, M.; Hoy, A.W. Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2001, 17, 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Inclusive Teaching: Preparing All Teachers to Teach All Students. 2020. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/2020teachers (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Suprayogi, M.N.; Valcke, M.; Godwin, R. Teachers and their implementation of differentiated instruction in the classroom. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 67, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Neve, D.; Devos, G.; Tuytens, M. The importance of job resources and self-efficacy for beginning teachers’ professional learning in differentiated instruction. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 47, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.; Tuytens, M.; Devos, G.; Kelchtermans, G.; Vanderlinde, R. Transformational school leadership as a key factor for teachers’ job attitudes during their first year in the profession. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2020, 48, 106–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geijsel, F.P.; Sleegers, P.J.C.; Stoel, R.D.; Kruger, M.L. The Effect of Teacher Psychological and School Organizational and Leadership Factors on Teachers’ Professional Learning in Dutch Schools. Elem. Sch. J. 2009, 109, 406–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhong, J.; Luo, M.; Lu, M. Academic Self-Efficacy, Social Support, and Professional Identity Among Preservice Special Education Teachers in China. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marschall, G. The role of teacher identity in teacher self-efficacy development: The case of Katie. J. Math. Teach. Educ. 2021, 25, 725–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.J.; Tsai, H.T.; Tsai, M.T. Linking transformational leadership and employee creativity in the hospitality industry: The influences of creative role identity, creative self-efficacy, and job complexity. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.Q.; Cooper, P.; Sin, K. The ‘Learning in Regular Classrooms’ initiative for inclusive education in China. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2018, 22, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. China’s Education Modernization 2035; The State Council of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2019-02/23/content_5367987.htm (accessed on 23 February 2019).

- Zhao, M.J.; Cheng, L.; Fu, W.Q.; Ma, X.C.; Chen, X.Y. Measuring parents’ perceptions of inclusive school quality in China: The development of the PISQ scale. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2022, 68, 824–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, T.; Haiyan, Q. Leadership and Culture in Chinese Education. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2000, 20, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, S. Examining principal leadership effects on teacher professional learning in China: A multilevel analysis. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2023, 51, 1278–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model.—A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callero, P.L. Role-Identity Salience. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1985, 48, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U.; Loreman, T.; Forlin, C. Measuring teacher efficacy to implement inclusive practices. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2012, 12, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Guay, F.; Valois, P. Teaching to address diverse learning needs: Development and validation of a Differentiated Instruction Scale. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2013, 17, 1186–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical Mediation Analysis in the New Millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Hallinger, P. Unpacking the effects of culture on school leadership and teacher learning in China. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2020, 49, 214–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildisch, A.K.; Froese, F.J.; Pak, Y.S. Employee responses to a cross-border acquisition in South Korea: The role of social support from different hierarchical levels. Asian Bus. Manag. 2015, 14, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.A.; Meyer, J.P.; Wang, X.H. Leadership, Commitment, and Culture: A Meta-Analysis. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2013, 20, 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, J.; Zhou, X. Customer Cooperation and Employee Innovation Behavior: The Roles of Creative Role Identity and Innovation Climates. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 639531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Deng, M. A Narrative Inquiry of a Novice Resource Teacher’s Identity Building in Inclusive Education Settings—Based on the Perspective of Teacher Emotion. Chin. J. Spec. Educ. 2021, 250, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Grube, J.A.; Piliavin, J.A. Role identity, organizational experiences, and volunteer performance. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 26, 1108–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, L.; Wang, Y. The Effect of Transformational Leadership on the Attitude to Inclusive Education of Teachers Teaching in the Regular Classroom: A Moderated Mediation Model. Chin. J. Spec. Educ. 2022, 267, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Poon-McBrayer, K.F. School leaders’ dilemmas and measures to instigate changes for inclusive education in Hong Kong. J. Educ. Change 2017, 18, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMatthews, D.E.; Kotok, S.; Serafini, A. Leadership Preparation for Special Education and Inclusive Schools: Beliefs and Recommendations From Successful Principals. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2020, 15, 303–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M.; Sandill, A. Developing inclusive education systems: The role of organisational cultures and leadership. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2010, 14, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninkovic, S.; Knezevic-Floric, O.; Dordic, D. Transformational leadership and teachers’ use of differentiated instruction in Serbian schools: Investigating the mediating effects of teacher collaboration and self-efficacy. Educ. Stud. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Hartnell, C.A. Understanding transformational leadership-employee performance links: The role of relational identification and self-efficacy: Transformational leadership and performance. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demography | Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 207 | 29.1% |

| Female | 505 | 70.9% | |

| Teaching experience (years) | 0–5 | 123 | 17.7% |

| 5–10 | 131 | 18.4% | |

| 10–20 | 172 | 24.2% | |

| Over 20 | 283 | 39.7% | |

| Number of SEN students taught in a classroom | 1–2 | 620 | 87.1% |

| 3 and over | 92 | 12.9% | |

| School type | Primary | 452 | 63.5% |

| Secondary | 260 | 36.5% |

| Variables | Mean | SD | AVE | CR | PTL | TIRI | TEIP | TITB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTL | 3.653 | 1.259 | 0.848 | 0.981 | 1 | |||

| TIRI | 3.802 | 1.246 | 0.755 | 0.925 | 0.594 *** | 1 | ||

| TEIP | 3.828 | 0.996 | 0.756 | 0.981 | 0.501 *** | 0.687 *** | 1 | |

| TITB | 3.940 | 1.081 | 0.796 | 0.981 | 0.559 *** | 0.567 *** | 0.583 *** | 1 |

| β | SE | β/SE | 95% Bootstrap CIs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| PTL → TITB (direct effects) | 0.284 *** | 0.048 | 5.877 | 0.160 | 0.410 |

| PTL → TIRI → TITB | 0.097 * | 0.045 | 2.167 | 0.010 | 0.189 |

| PTL → TEIP → TITB | 0.059 ** | 0.021 | 2.826 | 0.016 | 0.125 |

| PTL → TIRI → TEIP → TITB | 0.144 *** | 0.035 | 4.103 | 0.066 | 0.254 |

| Total indirect effects | 0.301 *** | 0.032 | 9.290 | 0.222 | 0.387 |

| Total effects | 0.585 *** | 0.035 | 16.622 | 0.485 | 0.672 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, D.; Huang, L.; Huang, X.; Deng, M.; Zhang, W. Enhancing Inclusive Teaching in China: Examining the Effects of Principal Transformational Leadership, Teachers’ Inclusive Role Identity, and Efficacy. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030175

Wang D, Huang L, Huang X, Deng M, Zhang W. Enhancing Inclusive Teaching in China: Examining the Effects of Principal Transformational Leadership, Teachers’ Inclusive Role Identity, and Efficacy. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(3):175. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030175

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Dongsheng, Liang Huang, Xianhan Huang, Meng Deng, and Wanying Zhang. 2024. "Enhancing Inclusive Teaching in China: Examining the Effects of Principal Transformational Leadership, Teachers’ Inclusive Role Identity, and Efficacy" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 3: 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030175

APA StyleWang, D., Huang, L., Huang, X., Deng, M., & Zhang, W. (2024). Enhancing Inclusive Teaching in China: Examining the Effects of Principal Transformational Leadership, Teachers’ Inclusive Role Identity, and Efficacy. Behavioral Sciences, 14(3), 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030175