Negative Acts in the Courtroom: Characteristics, Distribution, and Frequency among a National Cohort of Danish Prosecutors

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Occupational Mental Health among Prosecutors

1.2. Negative Acts among Legal Professionals

1.3. Existing Knowledge of Negative Acts among Legal Professionals

2. Framework for Characterizing the Negative Acts Reported by Danish Prosecutors

2.1. Stress-as-Offense-to-Self

2.2. Illegitimate Behavior and Incivility

3. Aim of the Current Study

4. Method

4.1. Procedure

4.2. Participants

4.3. Data Analysis

- The first and last author independently read the case material in its full length and continuously coded the data informed by the SOS theory.

- The first and last author discussed the initial coding to characterize the negative acts reported by the prosecutors. This included a discussion of any uncoded data that was either grouped with an existing code or given its own additional category. At this stage, codes from Cortina and colleagues [29] were added to the coding tree, and a total of ten subcodes of illegitimate behavior were added to refine this category.

- The first author recoded the data, focusing on the codes from Cortina and colleagues [29], distributing the data within the illegitimate behavior to these subcodes.

- The last author perused a random sample of the coded case material in accordance with the coding scheme. Upon disagreement, challenges related to the clarity or applicability of the categories or to the match between categories and data were discussed until agreement. This process was repeated three times.

- The first and last author met and finalized the recoding of the data to determine the coding of the individual descriptions. Disagreements were discussed until resolved.

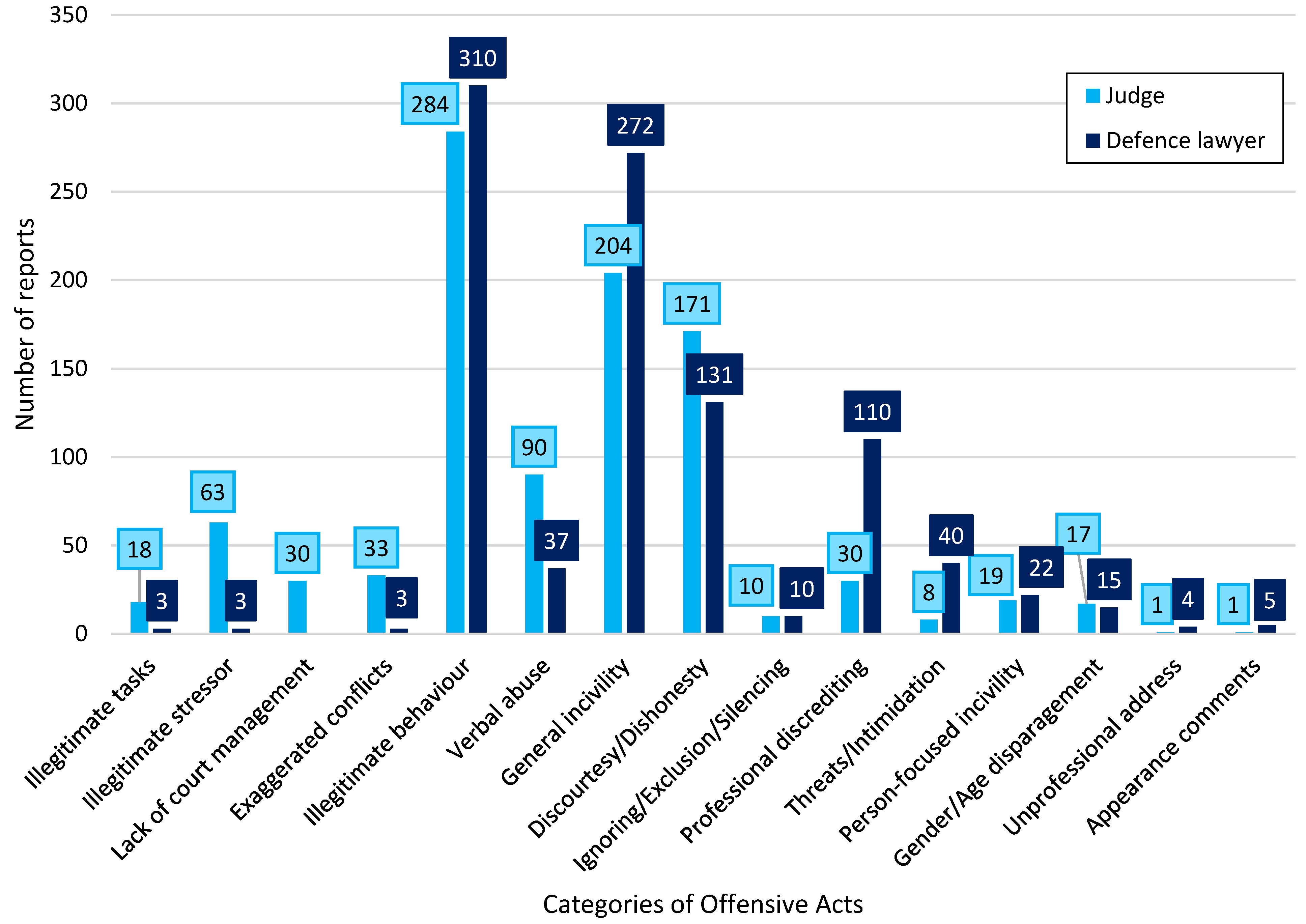

5. Results

5.1. Reported Sources of Negative Acts

5.2. Gender

5.3. Seniority

6. Discussion

6.1. Differences in Demographic Characteristics and Perceived Source

6.2. Possible Antecedents of Negative Acts in the Danish Courtrooms

6.3. Implications for Prevention

6.4. Methodological Considerations and Directions for Future Research

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prosecution Service. Available online: https://anklagemyndigheden.dk/da/om-anklagemyndigheden (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- The Ministry of Justice. The Administration of Justice Act; Vol. Consolidated Act 2022-12-25 No. 1655; The Ministry of Justice: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Justice and Consumers. The 2022 EU Justice Scoreboard—Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Central Bank, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Luxemb. Publ. Off. Eur. Union 2022. [CrossRef]

- Courts of Denmark. Key Figures on Case Flow and Processing Times; The Danish Courts: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Molen, H.F.; Nieuwenhuijsen, K.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W.; De Groene, G. Work-Related Psychosocial Risk Factors for Stress-Related Mental Disorders: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leclerc, M.-È.; Wemmers, J.-A.; Brunet, A. The Unseen Cost of Justice: Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Canadian Lawyers. Psychol. Crime Law 2019, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léonard, M.-J.; Vasiliadis, H.-M.; Leclerc, M.-È.; Brunet, A. Traumatic Stress in Canadian Lawyers: A Longitudinal Study. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2021, 15, S259–S267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, A.P.; Albert, L.; Besser, A.; Smith, D.; Zelenski, A.; Rosenkranz, S.; Neria, Y. Secondary Traumatic Stress in Attorneys and Their Administrative Support Staff Working With Trauma-Exposed Clients. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2011, 199, 946–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rønning, L.; Blumberg, J.; Dammeyer, J. Vicarious Traumatisation in Lawyers Working with Traumatised Asylum Seekers: A Pilot Study. Psychiatry Psychol. Law 2020, 27, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilal, A.; Batool, P.D.S.S. Construction and Validation of Occupational Stress Scale for Public Prosecutors. Progress. Res. J. Arts Humanit. PRJAH 2021, 3, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job Burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarcon, G.M. A Meta-Analysis of Burnout with Job Demands, Resources, and Attitudes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopmeijer, J.M.; Schutgens, C.A.E.; Kappe, F.R.; Gubbels, N.; Visscher, T.L.S.; Jongen, E.M.M.; Bovens, R.H.L.M.; de Jonge, J.M.; Bos, A.E.R.; Wiers, R.W. The Role of Performance Pressure, Loneliness and Sense of Belonging in Predicting Burnout Symptoms in Students in Higher Education. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vang, M.L.; Hansen, N.B.; Elklit, A.; Thorsen, P.M.; Høgsted, R.; Pihl-Thingvad, J. Prevalence and Risk-Factors for Burnout, Posttraumatic Stress, and Secondary Traumatization among Danish Prosecutors: Findings from a Pilot-Study. Psychol. Crime Law 2023, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, P.M.; Burr, H.; Rose, U.; Clausen, T.; Balducci, C. Antecedents of Workplace Bullying among Employees in Germany: Five-Year Lagged Effects of Job Demands and Job Resources. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Gupta, U.; Wadhwa, S. Known and Unknown Aspects of Workplace Bullying: A Systematic Review of Recent Literature and Future Research Agenda. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2020, 19, 263–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Einarsen, S. What We Know, What We Do Not Know, and What We Should and Could Have Known about Workplace Bullying: An Overview of the Literature and Agenda for Future Research. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2018, 42, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillien, E.; De Cuyper, N.; De Witte, H. Job Autonomy and Workload as Antecedents of Workplace Bullying: A Two-Wave Test of Karasek’s Job Demand Control Model for Targets and Perpetrators. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Einarsen, S. Outcomes of Exposure to Workplace Bullying: A Meta-Analytic Review. Work Stress 2012, 26, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodboy, A.K.; Martin, M.M.; Knight, J.M.; Long, Z. Creating the Boiler Room Environment: The Job Demand-Control-Support Model as an Explanation for Workplace Bullying. Commun. Res. 2017, 44, 244–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devonish, D. Job Demands, Health, and Absenteeism: Does Bullying Make Things Worse? Empl. Relat. 2013, 36, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omari, M.; Paull, M. ‘Shut up and Bill’: Workplace Bullying Challenges for the Legal Profession. Int. J. Leg. Prof. 2013, 20, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmer, N.; Jacobshagen, N.; Meier, L.L.; Elfering, A. Occupational Stress Research: The Stress-As-Offense-To-Self Perspective. In Occupational Health Psychology: European Perspectives on Research, Education and Practice; Houdmont, J., McIntyre, S., Eds.; Nottingham University Press: Nottingham, UK, 2007; pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Semmer, N.; Tschan, F.; Jacobshagen, N.; Beehr, T.A.; Elfering, A.; Kälin, W.; Meier, L.L. Stress as Offense to Self: A Promising Approach Comes of Age. Occup. Health Sci. 2019, 3, 205–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmer, N.; Jacobshagen, N.; Keller, A.C.; Meier, L.L. Adding Insult to Injury: Illegitimate Stressors and Their Association with Situational Well-Being, Social Self-Esteem, and Desire for Revenge. Work Stress 2021, 35, 262–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Danish Association of Judges. User Survey for The Danish Association of Judges—Report; The Danish Association of Judges: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of Justice. Law on Changing the Administration of Justice Act; The Danish Association of Judges: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010; Volume 186.

- Andersson, L.M.; Pearson, C.M. Tit for Tat? The Spiraling Effect of Incivility in the Workplace. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, L.M.; Lonsway, K.A.; Magley, V.J.; Freeman, L.V.; Collinsworth, L.L.; Hunter, M.; Fitzgerald, L.F. What’s Gender Got to Do with It? Incivility in the Federal Courts. Law Soc. Inq. 2002, 27, 235–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallant, J. Non-Parametric Statistic. In SPSS Survival Manual; Open University Press McGraw-Hill Education: London, UK, 2020; pp. 221–250. ISBN 978-1-00-311745-2. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Warnes, G.R.; Bolker, B.; Lumley, T.; Johnson, R.C. Gmodels: Various R Programming Tools for Model Fitting. 2022. Available online: https://rdrr.io/cran/gmodels/ (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Hershcovis, M.S. “Incivility, Social Undermining, Bullying…oh My!”: A Call to Reconcile Constructs within Workplace Aggression Research. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 499–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.F.; Levine, K.L. Career Motivations of State Prosecutors. GEORGE Wash. LAW Rev. 2018, 86, 1667–1710. [Google Scholar]

- Özer, G.; Escartín, J. The Making and Breaking of Workplace Bullying Perpetration: A Systematic Review on the Antecedents, Moderators, Mediators, Outcomes of Perpetration and Suggestions for Organizations. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2023, 69, 101823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Danish Association of Judges. The Working Conditions of Judges. In Report from the Work Group on the Working Conditions of Judges; The Danish Association of Judges: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Main- and Subcodes | % | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Illegitimate task | 3.2% | ‘When you have to play-pretend as a janitor and move the chairs and see to the IT in court’. ‘A judge asked me to go outside and ask the municipality to stop cutting the grass, because it was noisy’. ‘Judges remarking on their appendix lacking numbering, is not clipped together, etc.’ |

| Illegitimate stressor | ||

| Lack of court management | 4.4% | ‘At one point, a defense lawyer almost started to interrogate me without the judge intervening, even though I called it to the attention of the court’. ‘A lack of court management resulting in the defense lawyer being allowed to verbally abuse the prosecutor …’. |

| Conflicts arising or exaggerated by illegitimate stressors | 5.5% | ‘A judge who yells or scolds—even though it isn’t the prosecutor’s fault that the problem has arisen’. ‘Verbal abuse from a judge due to a missing mental examination that another prosecutor had decided wouldn’t be necessary’. |

| Illegitimate behavior | ||

| Verbal abuse | 18.0% | ‘A judge who … thrashed the pile of appendices to the floor, yelled “we won’t begin until this has been cleaned up” and left the room’. ‘I have experienced being verbally harassed by a defense lawyer, who pounded in the table with his hand and screamed that he bloody didn’t want to be interrupted’. ‘A judge yelled at me and called me offensive things in front of the defense lawyers’. |

| General incivility | ||

| Disrespect or dishonesty | 44.8% | ‘Judges and defense lawyers who roll their eyes at me’. ‘A defense lawyer outright lied in their procedure about what I had just said, it was extremely unpleasant’. |

| Ignoring, exclusion, or silencing | 3.1% | ‘An experienced defense lawyer interrupts and interferes in the opening hearing of the accused. The interference is irrelevant and unnecessary, the tone of voice is unpleasant and blaming, and it happens with the sole purpose of rattling me and destroying my plan for questioning’. ‘A judge refused to answer my question, as it didn’t suit him. He ignored me seven times, after which he at last said: “I don’t feel like answering your question”’. |

| Professional discrediting | 20.7% | ‘Defense lawyers insinuating that you have destroyed evidence or are not objective’. ‘I’ve had a judge ask me if we didn’t learn anything in law school anymore’. |

| Threats or intimidation | 6.8% | ‘A defense lawyer threatened to report me and an investigator to the Independent Police Complaints Authority’. ‘Defense lawyers who degrade the prosecutor and intimidate’. |

| Person-focused incivility | ||

| Gender or age disparagement | 5.4% | ‘Both judges and defense lawyers have several times given personally and degrading comments, among these, especially comments concerning the fact that I’m a woman’. ’I have been called ’the young prosecutor’ several times’. |

| Unprofessional address | 1.0% | ’When the phrase ”you have” rather than “the Prosecution Service has” is used’ ’Judge asking if it is Huey, Dewey, or Louie that represents the Prosecution Service today (it is degrading)’. |

| Appearance comments | 1.2% | ‘As a young prosecutor, the defense lawyer said during a procedure, that my procedure was far off and that nothing else were to be expected when the prosecutor was a blonde’. ‘A defense lawyer: as you stand there in your dress, you look like someone from a classical painting’. |

| Negative Acts, Present | Men | Adj. Std. R | Women | Adj. Std. R | χ2, p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| Illegitimate tasks | <5 | NA | −2.4 | 21 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 5.737, p = 0.017 |

| Illegitimate stressor | |||||||

| Lack of court management | 9 | 4.9 | 0.5 | 20 | 4.0 | −0.5 | 0.278, p = 0.598 |

| Exaggerated conflicts | 11 | 6.0 | 0.4 | 26 | 5.2 | −0.4 | 0.172, p = 0.678 |

| Illegitimate behavior | |||||||

| Verbal abuse | 17 | 9.3 | −3.6 | 107 | 21.4 | 3.6 | 13.223, p < 0.001 |

| General incivility | |||||||

| Discourtesy/dishonesty | 90 | 49.2 | 1.4 | 215 | 43.0 | −1.4 | 2.070, p = 0.150 |

| Ignoring/exclusion/silencing | <5 | NA | −0.8 | 17 | 3.4 | 0.8 | 0.663, p = 0.416 |

| Professional discrediting | 37 | 20.2 | −0.2 | 105 | 21.0 | 0.2 | 0.050, p = 0.824 |

| Threats/intimidation | 10 | 5.5 | −0.9 | 37 | 7.4 | 0.9 | 0.783, p = 0.376 |

| Person-focused incivility | |||||||

| Gender/age disparagement | 12 | 6.6 | 0.8 | 25 | 5.0 | −0.8 | 0.634, p = 0.426 |

| Unprofessional address * | 0 | 0.0 | −1.6 | 7 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 2.589, p = 0.199 |

| Appearance comments * | <5 | NA | −0.9 | 7 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.843, p = 0.689 |

| Negative Acts, Present | Assistant Prosecutor | Adj. Std. R | Prosecutor or Higher | Adj. Std. R | χ2, p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| Illegitimate tasks | 8 | 4.3 | 1.0 | 14 | 2.8 | −1.0 | 0.926, p = 0.336 |

| Illegitimate stressor | |||||||

| Lack of court management | <5 | NA | −2.2 | 27 | 5.4 | 2.2 | 4.759, p = 0.029 |

| Exaggerated conflicts | 13 | 6.9 | 1.0 | 25 | 5.0 | −1.0 | 0.948, p = 0.330 |

| Illegitimate behavior | |||||||

| Verbal abuse | 44 | 23.4 | 2.2 | 80 | 16.0 | −2.2 | 5.017, p = 0.025 |

| General incivility | |||||||

| Discourtesy/dishonesty | 92 | 48.9 | 1.3 | 216 | 43.3 | −1.3 | 1.762, p = 0.184 |

| Ignoring/exclusion/silencing | 6 | 3.2 | 0.1 | 15 | 3.0 | −0.1 | 0.016, p = 0.900 |

| Professional discrediting | 35 | 18.6 | −0.8 | 107 | 21.4 | 0.8 | 0.665, p = 0.415 |

| Threats/intimidation | 10 | 5.3 | −1.0 | 37 | 7.4 | 1.0 | 0.941, p = 0.332 |

| Person-focused incivility | |||||||

| Gender/age disparagement | 8 | 4.3 | −0.8 | 29 | 5.8 | 0.8 | 0.649, p = 0.420 |

| Unprofessional address * | <5 | NA | 0.9 | <5 | NA | −0.9 | 0.854, p = 0.399 |

| Appearance comments * | <5 | NA | −0.9 | 7 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.900, p = 0.690 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hovman, A.R.; Pihl-Thingvad, J.; Elklit, A.; Roessler, K.K.; Vang, M.L. Negative Acts in the Courtroom: Characteristics, Distribution, and Frequency among a National Cohort of Danish Prosecutors. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14040332

Hovman AR, Pihl-Thingvad J, Elklit A, Roessler KK, Vang ML. Negative Acts in the Courtroom: Characteristics, Distribution, and Frequency among a National Cohort of Danish Prosecutors. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(4):332. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14040332

Chicago/Turabian StyleHovman, Amanda Ryssel, Jesper Pihl-Thingvad, Ask Elklit, Kirsten Kaya Roessler, and Maria Louison Vang. 2024. "Negative Acts in the Courtroom: Characteristics, Distribution, and Frequency among a National Cohort of Danish Prosecutors" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 4: 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14040332

APA StyleHovman, A. R., Pihl-Thingvad, J., Elklit, A., Roessler, K. K., & Vang, M. L. (2024). Negative Acts in the Courtroom: Characteristics, Distribution, and Frequency among a National Cohort of Danish Prosecutors. Behavioral Sciences, 14(4), 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14040332