Abstract

Psychotherapy for individuals with psychosis is an effective treatment that promotes recovery in various ways. While there is strong quantitative evidence across modalities, less is known from the patient’s perspective. There are many varied forms of psychotherapy, and gaining the patient’s perspective can improve understanding of salient elements of psychotherapy and increase engagement, ultimately improving recovery rates. The purpose of this review is to identify and integrate data from published studies of patient perspectives of psychotherapy for psychosis to understand essential elements across approaches, differences between approaches, and how psychotherapy impacts recovery. We aimed to understand further: what are the perceptions about individual psychotherapy from the perspective of individuals with psychosis? The current study was a systematic review using PRISMA guidelines of studies that included qualitative interviews with persons with experiences of psychosis who participated in psychotherapy. All three authors participated in the literature search using Pubmed, APA PsycInfo, and Psychiatry Online. We identified N = 33 studies. Studies included cognitive therapies, acceptance and mindfulness approaches, trauma therapies, metacognitive therapy, and music therapy. All studies reported participants’ perceived benefit with the therapeutic relationship as especially salient. Participants described diverse aspects of objective (e.g., symptoms, functioning) and subjective (e.g., self-experience or quality of life) recovery improvements, with perceived mechanisms of change, and with music therapy having some unique benefits. Participants also reported challenges and suggestions for improvement. Study findings highlight the salient aspects of psychotherapy identified by patients that may help therapists to individualize and improve approaches to psychotherapy when working with individuals experiencing psychosis. Overall, findings support the potential for integrative psychotherapy approaches for maximal treatment personalization.

1. Introduction

1.1. Psychosis and Treatment

Experiencing the onset of a serious mental illness (SMI) such as psychosis is a life-changing event that affects all areas of one’s life, including relationships, everyday functioning, sense of self, and one’s experience of the world [1]. Psychosis is a mental illness that affects people in various ways, and may include experiences of auditory or visual hallucinations, delusional beliefs, negative symptoms, cognitive challenges, and various functional difficulties [1,2]. We use the term ‘psychosis’ to include psychotic disorders with traditional diagnostic labels such as schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. This term will be used throughout our study as an intentionally broad term to encompass the experience of many individuals. Mental healthcare is important to help persons with psychosis return to their lives and find ways to engage in the world in a meaningful way. Individuals with SMI often utilize a range of mental health treatments that may address psychological distress, unremitting symptoms, loss of sense of self, or functional difficulty. For instance, psychosocial treatments, such as individual psychotherapy, may offer coping skills to manage symptoms, psychoeducation to understand diagnosis and treatment, and/or a dialogical space to navigate changes, gain perspective, and learn how to live with mental illness. National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend initiation of mental health intervention after the first episode of psychosis, including medication management, psychotherapy, and other psychosocial treatments [1,2]. While antipsychotic medication is considered a first-line treatment, some individuals may not want to take medications due to personal preference, lack of desired benefit, or potential side effects. Psychotherapy is a good alternative to medication, as it offers cognitive and behavioral mechanisms to allow individuals to manage their mental health through lifestyle changes, gaining understanding of oneself or others, and cognitive strategies. The vast majority of psychotherapy research for persons with psychosis included patients who were taking antipsychotic medication alongside psychotherapy; however, research has more recently explored the effectiveness of individual psychotherapy on its own [3,4]. Moreover, one recent study identified that immediate antipsychotic treatment after psychosis onset was associated with poorer five-year outcomes [5]. This suggests that there is a subgroup of patients who do not need immediate antipsychotic treatment and perhaps some that may benefit from psychosocial treatments such as psychotherapy as their primary treatment. It is important to continue to study individual psychotherapy as a fundamental and potentially stand-alone treatment for persons with psychosis, and to further understand the essential elements of psychotherapy that maximize its effectiveness.

1.2. Recovery after Psychosis

Recovery is a complex concept that has evolved alongside continued development of psychotherapy. Importantly, there is a distinction between objective recovery (i.e., outcome measured and defined by the clinician) versus subjective recovery (i.e., process measured and defined by the patient) [6]. Traditional models often focused on reduction or remission in symptoms and functional improvements within the scope of objective recovery. Grassroots movements in the 1980s and 1990s represented a paradigm shift that incorporated consumer definitions of recovery [7]. From this movement came the concept of subjective or personal recovery, which is a deeply personal process that involves changing one’s perspective, values, or roles. It is defined and assessed by the person experiencing psychosis themselves. It includes the development of life pursuits and meaning of one’s life [8]. Alongside the enhancement of recovery as a personal process rather than simply remission of symptoms, the aims of psychotherapy for individuals with psychosis have evolved to include more optimistic promotion of functional recovery and meaning-making [9].

As a more nuanced understanding of recovery developed, multiple psychotherapy modalities were developed with differing treatment foci and approaches. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Psychosis (CBTp) is one of the most well-established psychotherapies with numerous randomized-controlled trials that focuses on improving unhelpful thought patterns and promoting coping skills [10,11]. Acceptance and compassion-based treatments such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Compassion-Focused Therapy (CFT) are other forms of psychotherapy with a growing evidence base that focus on accepting psychological difficulties and improving compassion towards oneself [12,13]. Metacognitive therapies have emerged in recent years as other effective forms of psychotherapy. For example, Metacognitive Reflection and Insight Therapy (MERIT) is an integrative approach that helps individuals improve metacognition or understand themselves, others, and their place in the world so they can manage their mental illness, improve relationships, and improve quality of life [14,15]. Art and music therapy are forms of psychotherapy that utilize creative techniques to help people express themselves while understanding psychological and emotional aspects of art or music and how it might relate to themselves and their emotional experiences. These therapies are often offered in a group setting, but are sometimes offered as an individual psychotherapy [16]. Finally, as it is common for individuals with SMI to have experienced some form of trauma, there has been a resurgence in further understanding acceptability of trauma therapies for individuals with psychosis [17].

1.3. The Importance of Qualitative Research in Understanding Recovery

Traditionally, quantitative methods have been favored when researching the effectiveness and impact of psychotherapy for individuals with psychosis, most often using objective recovery definitions and measurement (e.g., symptoms). Quantitative research is helpful with gaining precise measurements to understand the degree of change in desired psychotherapy outcomes. Qualitative research is another potentially valuable avenue to gain important information about psychotherapy with data from interviews, for example, by understanding themes or patterns across interviews to understand the patient’s point of view. However, it is used less often, perhaps because has been regarded as “unscientific” or less rigorous than quantitative research [18]. This has led to a lack of research focused on the perspective of the patient and their experiences of psychotherapy. Without the patient perspective, clinicians may risk having a one-sided view of the important elements of psychotherapy, as studies have traditionally been designed and interpreted by researchers without asking the patient themselves what they think. Consistent with the paradigm shift from objective to more personal and pertinent aspects of an individual’s life, as well as to better understand the consumer’s definition of recovery, qualitative measurement can better capture the process of subjective recovery from the perspective of the patient themselves. In fact, researchers have noted that often times there is great discrepancy between what patients and therapists value in the working alliance, and therapists are only accurately able to identify what the patient believes are the most impactful moments in sessions about one-third of the time [19]. In addition, compared to therapists, patients appear to place greater emphasis on helpfulness, joint participation in the work of therapy, and negative signs of the alliance [20].

Recently, the importance of qualitative research has started to gain traction [21]. We propose that one way to further understand important factors relevant for a range of psychotherapy approaches is by examining the patient perspective across approaches. It is important to know how patients perceive psychotherapy and how it impacts diverse aspects of recovery. There is some evidence to support that patient perception of treatment could affect both engagement [22] and outcomes [23]. Qualitative studies about psychotherapy can complement quantitative studies by adding rich, contextual, and in-depth accounts of a person’s experience that can further enhance the breadth of information afforded by quantitative studies [18]. Interviewing patients allows them to speak in their own voice to best contribute to the development and improvement of treatments, and helps investigators compare their own perception of reality and definitions of recovery using the patients’ ideas. Furthermore, subjective and objective measures of functioning can offer different aspects of recovery from the clinician and patient that can be integrated to provide a more comprehensive picture [24]. Identifying the most salient aspects of treatment for patients may help better distinguish the different mechanisms of change contributing to recovery and further improve treatments.

1.4. Aims and Scope

The purpose of this review is to identify and carry out an integrated analysis of qualitative studies that include interviews of patients experiencing psychosis who participated in some form of individual psychotherapy. We aimed to understand further: what are the perceptions about individual psychotherapy from the perspective of individuals with psychosis? We hoped to include a wide range of studies with diverse modalities and approaches to understand broadly how individuals with psychosis experience individual psychotherapy. To our knowledge, this is the first published review with this focus. Holding et al. (2016) [25] published a review that synthesized individuals’ experience of psychological therapy for psychosis, although they included individual psychotherapy, the review was not focused on individual psychotherapy specifically and the majority of studies were group or family therapy. Additionally, Wood et al. (2015) [26] published a review of qualitative studies exploring patients’ experiences of CBT for psychosis. Distinct from these and other previous reviews, this is the first systematic review the authors are aware of that specifically aims to explore individual psychotherapy, across modalities, from the perspective of persons with psychosis. It is important to review diverse psychotherapy approaches to identify and further understand any similarities and differences across modalities. Specifically, we aim to integrate the findings of these articles to further understand, from the perspective of people with psychosis: (1) reported benefits of psychotherapy and how psychotherapy impacts recovery; (2) the experience of the psychotherapy process and what contributes to outcomes; and (3) critiques or areas of need. We intended to include a broad inclusion of studies as this is the first study of its kind and we aimed to gain a comprehensive understanding of patient experience from our findings. We hope these findings will improve our understanding of the essential elements of psychotherapy that promote recovery for persons with psychosis.

2. Method

2.1. Approach and Design

The current study was a systematic review using guidelines from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [27,28]. Our research question was to understand the perceptions of individuals with psychosis who participated in individual psychotherapy. We intended to conduct a broad search to understand a range of psychotherapy approaches and how they impact persons with psychosis.

2.2. Study Eligibility and Exclusion Criteria

Qualitative studies consisting of interviews with adults aged 18 or older with psychosis (i.e., with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or other schizophrenia/psychosis spectrum disorder) who participated in individual psychotherapy were included. We used the American Psychological Association’s (APA) definition of psychotherapy as a guide: “any psychological service provided by a trained professional that primarily uses forms of communication and interaction to assess, diagnose, and treat dysfunctional emotional reactions, ways of thinking, and behavior patterns” (American Psychological Association, 2024) [29]. We included studies related to all forms of individual psychotherapy (e.g., psychodynamic, cognitive, behavioral, humanistic, art/music, and integrative) with any duration of treatment. Eligible studies included at least one primary aim related to exploring patient perspectives of psychotherapy. This criterion was intentionally broad to capture a range of diverse study aims. We included studies with adolescent aged participants (e.g., early psychosis) if the study also included adults. Studies that included a range of diagnoses (e.g., a serious mental illness population) were included if they included individuals with psychosis or schizophrenia spectrum disorders within the sample. Studies with a comparison group or alongside clinician interviews were included as long as they included patient data. We were inclusive of additional participant demographic factors (e.g., we did not exclude based on lower or upper age limits, primary diagnosis, medication status, etc.). We included studies from all years of publication, with no restrictions on year of dissemination.

Studies that analyzed data from therapy which was not individual psychotherapy were not included, for example group therapy, family therapy, or case management. Studies investigating smart phone apps or other self-directed interventions (i.e., without a primary therapist as a major feature of the intervention) were not included. Studies that did not include individuals with a diagnosis of a primary psychotic disorder were not included, for example non-SMI diagnoses, clinical high risk for psychosis, or postpartum psychosis. Studies that aim to understand a very specific aspect of therapy (e.g., case formulation) or more broad aspects of recovery that were not specifically focused on psychotherapy (e.g., how psychiatric treatment affects recovery) were not included. Case studies were not included. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses were excluded. Unpublished manuscripts and conference abstracts were not included. Articles that were not in the English language were not included.

2.3. Search Strategy and Article Selection

Three groups of search terms were included: (1) “psychosis”, OR “schizophrenia”, OR “schizoaffective disorder”, OR “serious mental illness”, OR “severe mental illness”; (2) “qualitative”; (3) “psychotherapy” OR “therapy”. In terms of PICOS guidelines for searches [30]: Population: individuals with psychosis (i.e., with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or other schizophrenia/psychosis spectrum disorder); Intervention: individual psychotherapy as defined by APA guidelines above; Comparison: qualitative data; Outcome: patient perceptions; and Study Type: qualitative method. Taken together, the research question is: Using qualitative data/method, what are the perceptions of individual psychotherapy from the perspective of individuals with psychosis? The quality of studies was assessed by examining how well each study met the inclusion criteria with an examination of the study’s aims, methodology, and patient sample by screening each title, abstract, and full text (if the title and abstract met inclusion criteria). Manual extraction was completed by all three authors for the first search using Pubmed. Search filters were applied for second (APA PsycInfo) and third (Psychiatry Online) searches by all three authors. Filters included: academic journals, qualitative study, interview, and English language.

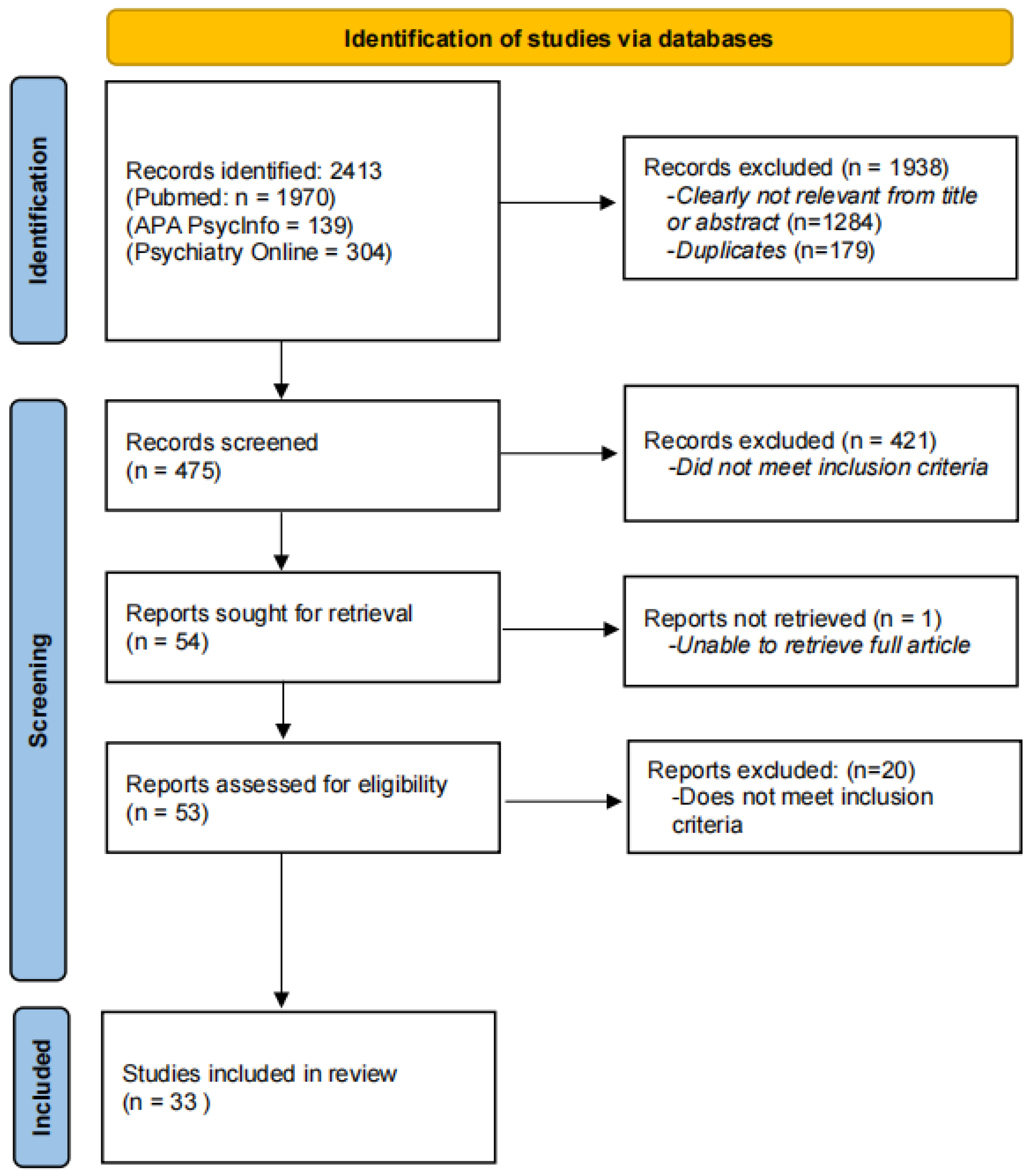

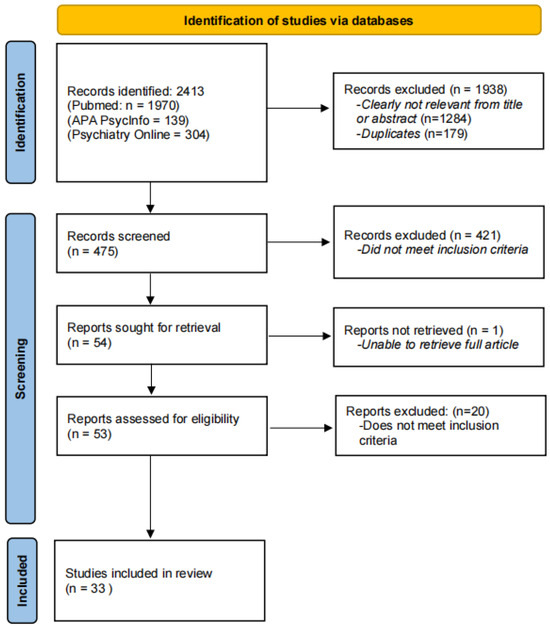

The search was conducted between October 2023 and March 2024 by all three authors. The date of the last search was 11 March 2024. Studies identified from searches were examined to ensure they met inclusion criteria, and consensus was reached for the final list. There were N = 2413 records identified across all three databases. Records were excluded due to not being relevant or duplicates (n = 1938). There were n = 475 screened, of which n = 54 were sought for retrieval as potential articles to include in the review (n = 421 did not meet inclusion criteria). There was n = 1 that the authors were unable to retrieve and n = 20 that did not meet inclusion criteria. All discrepancies were discussed among all three authors throughout the process. Studies included in the review included n = 33 articles. See Figure 1 for a detailed depiction of the study extraction process.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study extraction process.

2.4. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

All three authors conducted independent extraction of study characteristics, methodologies, and results, as well as assessment of the limitations of each study. Any discrepancies were reviewed by at least two authors as they arose. No automation tools or software were used. The sequence for data extraction proceeded as follows: first author (year of publication), country, type of therapy (# of sessions), participants and setting, aims, analysis, results/themes (subthemes). Setting of the study varied between included studies and was reported as the most specific value that was available. Reporting of the number of sessions varied between included studies, as such data are reported as a range when included, and otherwise as a mean value (when range was not available). LF manually collected data to be integrated, and the second and third authors checked the consolidated data for accuracy and consistency.

After studies were identified, a summary of findings including characteristics of studies and findings across studies was completed by LF, reviewed by the second and third author, and is presented to summarize results. We will describe psychotherapy approaches, patient demographics, and methodologies used. Findings will be described to summarize similarities and differences across studies.

The authors did not use any automation tools to assess risk of bias. To reduce risk, all three authors conducted independent searches using three search tools. After the first author consolidated the data, the second and third authors checked the data for accuracy and consistency to reduce bias. This was a qualitative review, so effect size and other statistical bias are not relevant. The majority of our studies only included one group, so there was not randomization considered. We were interested to understand patient’s perspective of psychotherapy, which can be achieved with a single group design. However, comparison groups could add more information and potentially reduce bias. The authors considered limitations of the different studies as a measure of quality.

2.5. Data Synthesis

All data were integrated using the qualitative and thematic data from included studies. Results from each study were evaluated by reading qualitative data line-by-line and reporting patterns or common themes across data. A summary overview of results, including characteristics of the data as well as themes, is included in the Results Section. Common themes across studies were found by evaluating themes within each study, and reading content of each theme to gain cohesive understanding of themes and identify patterns of themes across studies.

3. Results

After a thorough search using the above-stated search criteria, 2412 articles were initially identified via the databases. Following the removal of duplicates and articles that did not meet inclusion criteria, a total of 33 articles were selected for this review. The PRISMA flow diagram (for more details, see Section 2.3. Search Strategy and Article Selection) illustrates the exclusion of studies at each selection stage (Figure 1). The 33 full-text articles were included in the review to follow; their suitability was verified according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria and then subjected to data extraction (Table 1 and Table 2) and quality assessment.

Table 1.

Studies included in review.

Table 2.

Themes and subthemes across studies.

3.1. Study Characteristics

There were N = 33 studies that met inclusion criteria presented in Table 1 [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63]. Publication years ranged from 2003–2023. The majority of studies were recent, n = 20 (60.61%) that were from the past 6 years, from 2019–2024. All studies included qualitative data with reported themes, including interpretive phenomenological analysis, thematic analysis, discourse analysis, or grounded theory. Inductive phenomenological analysis explores how individuals make sense of their experiences. Thematic analysis focuses on themes/patterns within the data. The one study reporting discourse analysis described their interest in how the client positioned themselves in relation to the therapist. Grounded theory is concerned with using qualitative data to generate theories. The current review focused on each study’s reported themes. Regarding modality/approach of psychotherapies included, the most common specific modality reported was CBTp (n = 3) [48,51,56] or other types of cognitive therapies (n = 5) [33,36,46,49,60]. Beyond cognitive therapies, other evidence-based approaches were included. There were three studies that analyzed Metacognitive Reflection and Insight Therapy (MERIT) [40,52,54]. There were three studies that analyzed Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) [32,37,39] and one with compassionate imagery [43]. Several additional studies involved a form of trauma therapy, including one study each of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing EMDR [41], trauma-focused imaginal exposure [42], prolonged exposure [47], narrative exposure therapy [55], and two studies including trauma-integrated psychotherapy for psychosis (TRIPP) [61,62]. In addition, two studies analyzed a technology-enhanced/assisted psychotherapy: Slowmo [45] and virtual reality therapy for negative symptoms [38]. There were three studies analyzing music therapy [31,57,59]. Two studies focused on hearing voices, including Talking with Voices [53], Making Sense of Voices [58], and Relating Therapy [50]. Other studies tested newer approaches including interventions the Feeling Safe Program [35], Social Recovery Therapy [44], and Low-Intensity Psychological Therapy [63]. One study included participants who engaged in differing psychotherapy modalities [34].

The majority of studies included a cohesive sample of persons with psychosis, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder [32,33,34,35,36,38,40,43,44,45,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,56,60,61,62,63]. There were twelve studies which included a broader population of serious mental illness that included additional diagnoses (e.g., depression with psychotic features or post-traumatic stress disorder) along with psychosis [31,39,41,42,46,47,55,57,58,59,61,62]. One study included individuals with clinical high risk in addition to the individuals with early psychosis that fit inclusion criteria, thus it was included in the analysis [37]. The majority of studies were conducted in the United Kingdom [31,33,35,38,39,43,44,45,46,48,49,50,51,53,56,60,63], followed by Australia [32,42,61,62], the United States [36,47,52,54], The Netherlands [37,40,55], Norway [34,59], Germany [58], New Zealand [41], and South Africa [57]. The number of study participants ranged from four to twenty-five.

3.2. Aim 1: Perception of Benefit, Impact on Recovery, and Mechanisms of Change

Overall, participants across studies had positive views of psychotherapy and found it beneficial to their recovery in various ways. All studies included themes related to improvements or benefits following engagement in or completion of psychotherapy. One of the most salient benefits mentioned in all of the studies included in the review related to objective recovery outcomes, including improved symptoms, functioning, or achievement of goals (e.g., related to the specific psychotherapy presented, such as gaining control over voices) [32,33,34,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,45,47,49,50,51,52,54,55,56,58,59,61,63]. Studies also included themes related to improvements in subjective areas of recovery, for example, improved quality of life, sense of oneself or one’s identity, or self-confidence or self-compassion [31,34,35,40,41,42,44,45,52,53,54,55,57,59]. Others noticed a different relationship with the world overall [34,42,45] Participants also discussed specific parts of therapy that seemed to drive changes (i.e., mechanisms of change). This included improved agency or feeling in control [33,44,46,54], as well as new ways of thinking or meaning-making [35,39,46,48,54]. Others mentioned enhanced understanding of oneself [44,54,55], their illness, or their symptoms [39,53,56,60], or learning new skills (e.g., coping skills, tools, or intervention specific activities) [39,60,63]. Some mentioned emotional expression as cathartic [48], fulfilling [57], and a source of connecting with self and others [59].

3.3. Aim 2: The Experience of Psychotherapy

Regarding overall experience of psychotherapy, the most salient theme was reflection on the therapeutic relationship. Overall, participants had positive views of the relationship and found it to be instrumental in psychotherapy and recovery. Several mentioned that the therapeutic relationship felt similar to a friendship [31,34,35,55,56] and that it was an equal/collaborative relationship [31,56]. Important qualities participants mentioned included that their therapist was supportive and nonjudgmental [33,48,53,55,60]. Other descriptions included feeling acceptance and to have someone they were comfortable with and they could trust [35,45,48]. They felt it important to be respected and understood by their therapist [34,40,48,49,56]. They valued having someone who was flexible, personalized therapy, and listened to them [35,45,48]. Participants valued a therapist who cared about them and their life story [56]. Participants valued a therapist who challenged them [44,46], although some were off put when they felt the therapist was skeptical or questioning the validity of their thoughts [33]. One study with forty sessions mentioned that the timeframe helped them have adequate time to get to know and trust their therapist [40]. Another study reported that having a shared reality or language was helpful in therapy [34]. In a few studies, participants mentioned distrust in the therapist or lack of support as a barrier to psychotherapy [33,36,55]. For example, not feeling listened to sometimes led to lack of trust [49]. These were more often mentioned in studies with briefer interventions.

In general, participants experienced psychotherapy as challenging yet rewarding. Several studies reported participants as skeptical of psychotherapy at first, but felt it beneficial once they engaged [33,41,42,47,49]. Some studies reported that participants mentioned that psychotherapy was intense or emotionally burdensome [33,41,48]. At times, participants reported that psychotherapy brought distress to the surface as something to be worked on [44,48], yet at other times this distress was difficult for participants to tolerate [47]. Some reported that psychotherapy did not help or made symptoms worse [33,47,48].

Studies analyzing music therapy reported some participant experiences that were distinct from other modalities included in this study [31,57,59]. Participants valued creativity and found the intervention to be emotionally fulfilling. Participants felt a sense of freedom/liberation that was positive for them. At times, this meant freedom from symptoms, but often it was broader than that; music was a freeing experience that gave participants a sense of liberation within themselves during the process of music therapy. They were able to explore parts of themselves outside their illness that gave them a sense of identity and purpose. They were able to unleash creativity, playfulness, and express themselves. The self-expression was unique in that it was not limited by words as traditional talk therapy is, and it was a new way of self-expression for many. Participants described music therapy as therapeutic but different than traditional mental health treatment, and that it was distinct from other types of individual therapy. Participants also described music therapy as giving them greater connection to others and the world. For some, this was related to their connection with the therapist and engaging in an activity together as equals. Others mentioned that music therapy helped open an avenue for greater connection to others in the world (e.g., friends and family), attending concerts, or joining a local choir or band.

3.4. Aim 3: Critiques of Therapy

Several studies included participant critiques or suggestions for the psychotherapy. Participants often mentioned a need for personalization and flexibility when there was a perceived lack thereof [33,36,37]. Several studies reported participants desiring more time or feeling as though the therapy ended abruptly [36,38,39,48]. Some studies reported participants as having difficulty understanding concepts [37,39], technical issues [38,45], treatment as too structured, or not feeling as though the treatment was a good fit [37,39].

For a summary of common themes, see Table 2.

4. Discussion

The current study was a systematic review that included qualitative interviews with patients with psychosis who participated in individual psychotherapy. We aimed to ingrate data from qualitative studies to further understand the perceptions of individuals with psychosis who participated in individual psychotherapy. We included studies from a range of different approaches, including cognitive therapies, acceptance and mindfulness-based therapies, metacognitive therapy, trauma treatments, and music therapy. More specifically, we sought to understand: (1) reported benefits of psychotherapy and how psychotherapy impacts recovery; (2) the experience of the psychotherapy process and what contributes to outcomes; and (3) critiques or areas of need.

4.1. Psychotherapy Benefit on Objective and Subjective Recovery, and Mechanisms of Change

Participants in the included studies reported that psychotherapy helped with a range of distinct recovery outcomes, including both objective and subjective aspects of recovery. As expected, participants reported improvements in objective aspects of recovery, including symptoms, goals, and functioning. Approaches that emphasized objective recovery were those that were more structured and targeted symptoms or psychosocial functioning, such as CBT, ACT, and trauma therapies. Participants also reported improvements in subjective aspects of recovery such as sense of self, quality of life, self-compassion, and relationship with the world. Across all three Metacognitive Reflection and Insight Therapy (MERIT) studies, themes related to self-understanding were reported, including self-compassion, self-expression, and self-esteem [40,52,54]. Unique from many approaches included here, MERIT incorporates the development of understanding the narratives of one’s life to improve their sense of self and narrative identity [64]. Interestingly, one study reporting results from narrative exposure therapy, a type of trauma treatment for people with psychosis, also reported patient experience of increased self-knowledge through improved understanding of one’s life [55], supporting the idea that eliciting life narratives is an essential element in promoting self-understanding.

Participants noted aspects of psychotherapy that they thought contributed to change (i.e., mechanisms of change). The concept of agency appeared across different modalities as an important mechanism of change. Patients described the value in being able to take control of their lives and gain valuable skills/knowledge to gain mastery over difficulties. Agency is essential for individuals to manage mental health and decide how to engage in their lives beyond their illness. However, some individuals may have difficulty directing their own activities for example due to lack of motivation or negative symptoms. In this case, patients may need extra support to bolster agency. For instance, one study outlined how metacognitive intervention was essential for a patient to later engage with behavioral activation [65]. Other themes related to mechanism of change included gaining insight, a new way of thinking, and emotional expression. It is not surprising that these were the reported mechanisms of change, as cognitive and emotional work is an important focus of transtheoretical approaches, such as CBT, ACT, trauma, and metacognitive approaches. Lastly, learning skills was mentioned as an important part of therapy, for example, coping as a part of managing distress.

These findings provide further support for the idea that both objective and subjective aspects of recovery are important and should be assessed in psychotherapy [6]. It is possible that that different approaches may emphasize differing aspects of recovery, although it seems important to include a range of processes and outcomes to fully assess the effect of psychotherapy for the patient.

4.2. Therapeutic Relationship

Not surprisingly, the therapeutic relationship was reported as an essential part of psychotherapy across modalities. Participants described the alliance as helpful in working through difficult topics in therapy, and that once they trusted their therapist, the work was more meaningful/effective. This finding aligns with research suggesting that the therapeutic relationship or working alliance is an important predictor of treatment outcome [66]. Moreover, it has been suggested that often the patient’s experience of the working alliance is more predictive of successful outcomes of psychotherapy as compared to the clinician’s perspective [19]. One recent meta-analysis used to examine both patient and therapist perspective on the therapeutic alliance among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum, personality, and substance use disorders found that patients across all three diagnostic groups tended to estimate the therapeutic alliance as somewhat higher than did their therapists on quantitative measures [67]. Conversely, a few studies reported negative alliance, which illustrates that when alliance is poor, it has a detrimental effect on the experience of treatment. This aligns with previous studies that aim to understand how poor alliance affects psychotherapy. For instance, one study with male clients found that negative alliance was associated with rigid adherence to a therapeutic approach that was not a good fit for the patient [68]. In other words, the approach was inconsistent with the patient’s view of what was most helpful, important, or relevant.

In addition to the establishment of a positive therapeutic relationship and basic trust, understanding the patient’s subjective experience of therapy might be an essential factor to help facilitate recovery. For example, clinicians may benefit from promoting reflection about the patient’s perspective on the therapeutic alliance and the processes that are occurring within the therapy itself in order to integrate the patient’s feedback into ongoing therapy. One study found in particular found that using interventions to promote reflection on the progress in therapy within a given session was found to be correlated with higher scores on a measure of therapeutic alliance [69]. Research further suggests that when the therapist is willing and open to seek the patient’s perspectives and are non-defensive in accepting negative feedback, it is likely to contribute to a stronger alliance [70]. Thinking together and encouraging the patient to openly reflect on their ideas about the therapeutic alliance, their experience of what it is like to be in the presence of the therapist, and also what might they believe contributes to their own growth process, may help the therapist to gain a greater appreciation for the difficulties the patient is facing and working to overcome. This would allow for the therapist to gain perspective of the patient’s subjective experiences, fill any potential gaps between the patient and therapist’s perspectives, and ultimately, encourage the patient to better understand themselves.

4.3. Challenges/Barriers and Critiques of Psychotherapy

There were several challenges and criticisms of psychotherapy for people with psychosis that are important to consider. Several studies mentioned that participants found psychotherapy to be additionally distressing and they did not have the opportunity to resolve this distress during the course of treatment. It was also reported that some found psychotherapy to be too difficult in either content or structure. In addition, several studies reported that participants mentioned treatment being too brief. It is standard for evidence-based psychotherapy to be offered in the form of 12 sessions or less, and several studies included in this review followed this structure. However, there is evidence that psychotherapy for persons with psychosis should offer at least 16 sessions for significant improvement, and there is often greater benefit with increased number of sessions [71,72]. It is likely that patients vary in the number of sessions that is required as the “correct dose”, as such treatment providers should allow flexibility, when able, in an individual’s treatment plan. It is possible that an incorrect dose (i.e., not enough sessions) of therapy may contribute to unresolved distress that is increased as therapy begins and there is inadequate time to allow for distress to resolve. Important to consider are integrative treatments that could be useful to offer a range of content and structure to best individualize treatment [73]. For example, if a person needs a greater number of sessions or additional processing time to manage distress. Further, an integrative approach can bring together theories and approaches to support recovery, which is especially important, as personal recovery can have different meanings for different people [74]. As such, there are several models of integrative treatment that propose utilizing elements from existing theoretical models such as cognitive, interpersonal/intersubjective, developmental, psychodynamic, and metacognitive approaches [75,76,77,78,79].

4.4. Unexpected Findings: Unique Impact of Music Therapy and Similarities to Other Approaches

We included studies exploring patients’ views of music therapy, and findings suggest that this modality has a distinct impact on patients compared to other psychotherapy approaches. While traditional psychotherapy approaches focus on assisting individuals with coping strategies or understanding an identified psychological problem through talk therapy (e.g., positive symptoms, trauma memories, sense of self), music therapy is a distinct therapeutic method that uses music as an intervention to accomplish goals (e.g., emotion regulation, social skills, self-esteem) [80]. Participants who engaged in music therapy expressed value in the ability to be creative and feel free from psychiatric symptoms while engaging with music. Thus, music therapy may allow patients to explore aspects of themselves outside of psychiatric symptoms so they can improve their sense of self, gain confidence, and remember who they are despite their diagnosis. It might be that music therapy allows patients to better identify and express aspects of themselves that are difficult to communicate otherwise (e.g., in the form of words and verbal language) and thus non-traditional therapy approaches may provide unique benefits for patients and should be considered as part of a treatment plan. Importantly, music therapy may be able to inform talk therapy approaches to widen their treatment targets and improve the intersubjective space by integrating creativity within the therapy approach. For example, the use of play has been discussed as a means to allow the patient to engage in “creative mutual exploration” [81] and a means to communicate with the self and others [82]. Clinicians can inform their practice with forms of art, for example, considering jazz as a psychotherapy framework which utilizes improvisation with timing, risk-taking, and having a flexible role/ego [83]. Music therapy thus may be unique in its opportunity to explore aspects of subjective recovery that are often less of a focus in other forms of talk therapy. It may address an important gap in more traditional approaches of psychotherapy, which can sometimes risk reducing recovery to symptom reduction or alleviating dysfunction without allowing for a strengths-based model [84].

4.5. Limitations

The current study has limitations worth noting. We included a range of different studies with varied therapeutic approaches and varied qualitative methods. While this adds diversity to our review, we recognize that it also contributes to a lesser degree of cohesion. The majority of studies included had modest sample sizes, allowing for depth in findings, but may contribute to limited generalizability. Additionally, most of the studies were from cognitive or trauma-focused therapies. More research is needed to contribute to understanding of patient’s experience of other modalities such as psychodynamic, humanistic, or integrative approaches.

4.6. Summary and Conclusions

In summary, participants reported psychotherapy, in its many forms, as beneficial to diverse aspects of recovery, including both objective and subjective outcomes. They valued positive changes within themselves (e.g., changed thinking, skills obtained, improved insight, improved self-confidence), the therapeutic relationship, personalization, and flexibility in the treatment itself. Some of the important elements included were therapeutic alliance, learning, working through fears/challenges, sometimes referred to as common factors, which are consistently considered to be important aspects of therapy [85,86]. Importantly, experiences of psychotherapy for persons with psychosis varied greatly, supporting the idea that recovery is a complex process that can involve both objective outcomes and subjective, personal processes such as understanding oneself and one’s place in the world. It thus seems important when measuring progress and understanding recovery for persons with psychosis to have an integrative approach, by considering both objective, observable outcomes (e.g., reduction in symptoms, psychosocial functioning) and subjective processes (e.g., understanding of oneself and one’s life) [24,87].

This review has important clinical implications. We offer integrated findings from a range of psychotherapeutic approaches, further illustrating the diverse offerings for persons with psychosis. As each approach may be suited for certain individuals and psychological problems, and each person may have a different experience of treatment, it is important to continuously assess progress, subjective experience, and individualize treatment to best fit each person’s needs. As such, it is especially relevant to engage in shared decision-making practices with patients and determine a best fit for psychotherapy. For instance, determine with the patient what they are seeking in psychotherapy, whether or not they value structured learning, what they hope to achieve in psychotherapy, etc. Even when a single approach is used, there are factors that affect treatment outcomes such as third variables (e.g., insight) and common factors (e.g., the therapeutic relationship) [88] which may be gleaned from frequent feedback from the patient. For instance, it may be appropriate to designate session time for formal or informal feedback from the patient for qualitative or quantitative data including therapeutic alliance measures, recovery interviews, or how the patient understands changes resulting from psychotherapy. It seems important to highlight that integrative therapies may be a particularly helpful way to address the varied goals, needs, and accommodations for individuals seeking treatment. One example of this is Metacognitive Reflection and Insight Therapy (MERIT) [14], an integrative approach included in this review, which utilizes flexible elements rather than pre-determined sessions or agendas. One future direction includes further understanding and developing integrative therapy frameworks [9]. There are several effective offerings of psychotherapy for psychosis; it is likely that the most impactful approach for each person is one that is flexible and continuously adapts to integrate the unique needs of the person engaging in treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.A.F., J.D.H.-M. and C.N.W.; methodology, L.A.F.; validation, L.A.F., J.D.H.-M. and C.N.W.; investigation, L.A.F., J.D.H.-M. and C.N.W.; data curation, L.A.F., J.D.H.-M. and C.N.W.; writing—original draft preparation, L.A.F., J.D.H.-M. and C.N.W.; writing—review and editing, L.A.F., J.D.H.-M. and C.N.W.; visualization, L.A.F.; project administration, L.A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

This paper is dedicated to Paul H. Lysaker, who died in July 2023. He was our mentor and an innovator in developing integrative psychotherapy for psychosis. We hope to continue his legacy in the quest to understand and improve psychotherapy for persons with psychosis. We thank the many participants who have volunteered their time to share valuable perspectives from studies included in this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kuipers, E.; Yesufu-Udechuku, A.; Taylor, C.; Kendall, T. Management of psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: Summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ 2014, 348, g1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE. Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia in Primary and Secondary Care; NICE: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, A.P. Should people with psychosis be supported in choosing cognitive therapy as an alternative to antipsychotic medication: A commentary on current evidence. Schizophr. Res. 2019, 203, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.P.; Law, H.; Carter, L.; Sellers, R.; Emsley, R.; Pyle, M.; French, P.; Shiers, D.; Yung, A.; Murphy, E.K.; et al. Antipsychotic drugs versus cognitive behavioural therapy versus a combination of both in people with psychosis: A randomised controlled pilot and feasibility study. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, T.; Gauffin, T. The association of antipsychotic postponement with 5-year outcomes of adolescent first-episode psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. Open 2023, 4, sgad032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonhardt, B.L.; Huling, K.; Hamm, J.A.; Roe, D.; Hasson-Ohayon, I.; McLeod, H.J.; Lysaker, P.H. Recovery and serious mental illness: A review of current clinical and research paradigms and future directions. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2017, 17, 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, L.; White, W. The concept of recovery as an organizing principle for integrating mental health and addiction services. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2007, 34, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, W.A. Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc. Rehabil. J. 1993, 16, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, J.A.; Hasson-Ohayon, I.; Kukla, M.; Lysaker, P.H. Individual psychotherapy for schizophrenia: Trends and developments in the wake of the recovery movement. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2013, 6, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazell, C.M.; Hayward, M.; Cavanagh, K.; Strauss, C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of low intensity CBT for psychosis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 45, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, F.; Khoury, B.; Munshi, T.; Ayub, M.; Lecomte, T.; Kingdon, D.; Farooq, S. Brief cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis (CBTp) for schizophrenia: Literature review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 2016, 9, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heriot-Maitland, C.; Gumley, A.; Wykes, T.; Longden, E.; Irons, C.; Gilbert, P.; Peters, E. A case series study of compassion-focused therapy for distressing experiences in psychosis. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 62, 762–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yıldız, E. The effects of acceptance and commitment therapy in psychosis treatment: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2020, 56, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysaker, P.H.; Klion, R.E. Recovery, Meaning-Making, and Severe Mental Illness: A Comprehensive Guide to Metacognitive Reflection and Insight Therapy; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker, P.H.; Gagen, E.; Klion, R.; Zalzala, A.; Vohs, J.; Faith, L.A.; Leonhardt, B.; Hamm, J.; Hasson-Ohayon, I. Metacognitive reflection and insight therapy: A recovery-oriented treatment approach for psychosis. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 13, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.; Woods-Giscombe, C. Influence of dosage and type of music therapy in symptom management and rehabilitation for individuals with schizophrenia. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 37, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, A.; Keen, N.; van den Berg, D.; Varese, F.; Longden, E.; Ward, T.; Brand, R.M. Trauma therapies for psychosis: A state-of-the-art review. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2023, 97, 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L.A. Qualitative and mixed methods in mental health services and implementation research. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2014, 43, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, R.; Hayes, S. Clients’ perspectives on, experiences of, and contributions to the working alliance. In Working Alliance Skills for Mental Health Professionals; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- Bachelor, A. Clients’ and therapists’ views of the therapeutic alliance: Similarities, differences and relationship to therapy outcome. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2013, 20, 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renjith, V.; Yesodharan, R.; Noronha, J.A.; Ladd, E.; George, A. Qualitative Methods in Health Care Research. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munson, M.R.; Jaccard, J.; Scott, L.D., Jr.; Moore, K.L.; Narendorf, S.C.; Cole, A.R.; Shimizu, R.; Rodwin, A.H.; Jenefsky, N.; Davis, M.; et al. Outcomes of a metaintervention to improve treatment engagement among young adults with serious mental illnesses: Application of a pilot randomized explanatory design. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 69, 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delsignore, A.; Schnyder, U. Control expectancies as predictors of psychotherapy outcome: A systematic review. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 46, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.; Blanco, E.; Howie, H.; Rempfer, M. The discrepancy between subjective and objective evaluations of cognitive and functional ability among people with schizophrenia: A systematic review. Behav. Sci. 2023, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holding, J.C.; Gregg, L.; Haddock, G. Individuals’ experiences and opinions of psychological therapies for psychosis: A narrative synthesis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 43, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, L.; Burke, E.; Morrison, A. Individual cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis (CBTp): A systematic review of qualitative literature. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2015, 43, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychological Association. APA Dictionary of Psychology 2024; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansdell, G.; Meehan, J. Some light at the end of the tunnel: ’Exploring users’ evidence for the effectiveness of music therapy in adult mental health settings. Music Med. 2010, 2, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, T.; Farhall, J.; Fossey, E. The active therapeutic processes of acceptance and commitment therapy for persistent symptoms of psychosis: Clients’ perspectives. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2014, 42, 402–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birchwood, M.; Mohan, L.; Meaden, A.; Tarrier, N.; Lewis, S.; Wykes, T.; Davies, L.M.; Dunn, G.; Peters, E.; Michail, M. The COMMAND trial of cognitive therapy for harmful compliance with command hallucinations (CTCH): A qualitative study of acceptability and tolerability in the UK. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornestad, J.; Veseth, M.; Davidson, L.; Joa, I.; Johannessen, J.O.; Larsen, T.K.; Melle, I.; Hegelstad, W.T.V. Psychotherapy in psychosis: Experiences of fully recovered service users. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, J.; Kenny, A.; Mesaric, A.; Wilson, N.; Pinfold, V.; Kabir, T.; Freeman, D.; Waite, F.; Larkin, M.; Robotham, D.J. A life more ordinary: A peer research method qualitative study of the Feeling Safe Programme for persecutory delusions. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2022, 95, 1108–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornheimer, L.A.; Verdugo, J.L.; Krasnick, J.; Jeffers, N.; Storey, F.; King, C.A.; Taylor, S.F.; Florence, T.; Himle, J.A. A cognitive-behavioral suicide prevention treatment for adults with schizophrenia spectrum disorders in community mental health: Preliminary findings of an open pilot study. Soc. Work. Ment. Health 2023, 21, 538–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouws, J.; Henrard, A.; de Koning, M.; Schirmbeck, F.; van Ghesel Grothe, S.; van Aubel, E.; Reininghaus, U.; Myin-Germeys, I. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for individuals at risk for psychosis or with a first psychotic episode: A qualitative study on patients’ perspectives. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2023, 18, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, M.; Tomlin, P.; Robotham, D.; Green, P.; Griffiths, H.; Stahl, D.; Valmaggia, L. Virtual reality therapy for the negative symptoms of schizophrenia (V-NeST): A pilot randomised feasibility trial. Schizophr. Res. 2022, 248, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, B.E.; Morgan, S.; John-Evans, H.; Deere, E. ‘Monsters don’t bother me anymore’ forensic mental health service users’ experiences of acceptance and commitment therapy for psychosis. J. Forens. Psychiatry Psychol. 2019, 30, 594–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, S.; Hasson-Ohayon, I.; van Donkersgoed, R.; Aleman, A.; Pijnenborg, G.H.M. A qualitative evaluation of the effects of Metacognitive Reflection and Insight Therapy: ‘Living more consciously’. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2020, 93, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Every-Palmer, S.; Ross, B.; Flewett, T.; Rutledge, E.; Hansby, O.; Bell, E. Eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy in prison and forensic services: A qualitative study of lived experience. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2023, 14, 2282029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feary, N.; Brand, R.; Williams, A.; Thomas, N. ‘Like jumping off a ledge into the water’: A qualitative study of trauma-focussed imaginal exposure for hearing voices. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2022, 95, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forkert, A.; Brown, P.; Freeman, D.; Waite, F. A compassionate imagery intervention for patients with persecutory delusions. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2022, 50, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, B.; Berry, C.; Hodgekins, J.; Greenwood, K.; Fitzsimmons, M.; Lavis, A.; Notley, C.; Pugh, K.; Birchwood, M.; Fowler, D. A qualitative process evaluation of social recovery therapy for enhancement of social recovery in first-episode psychosis (SUPEREDEN3). Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2023, 51, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, K.E.; Gurnani, M.; Ward, T.; Vogel, E.; Vella, C.; McGourty, A.; Robertson, S.; Sacadura, C.; Hardy, A.; Rus-Calafell, M.; et al. The service user experience of SlowMo therapy: A co-produced thematic analysis of service users’ subjective experience. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2022, 95, 680–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, R.; Mansell, W.; Edge, D.; Carey, T.A.; Peel, H.; Tai, S.J. ‘It was me answering my own questions’: Experiences of method of levels therapy amongst people with first-episode psychosis. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grubaugh, A.L.; Veronee, K.; Ellis, C.; Brown, W.; Knapp, R.G. Feasibility and efficacy of prolonged exposure for PTSD among individuals with a psychotic spectrum disorder. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, A.; Good, S.; Dix, J.; Longden, E. “It hurt but it helped”: A mixed methods audit of the implementation of trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for psychosis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 946615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, K.; Gooding, P.A.; Awenat, Y.; Haddock, G.; Cook, L.; Huggett, C.; Jones, S.; Lobban, F.; Peeney, E.; Pratt, D.; et al. Acceptability of a novel suicide prevention psychological therapy for people who experience non-affective psychosis. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2023, 96, 560–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayward, M.; Bogen-Johnston, L.; Deamer, F. Relating Therapy for distressing voices: Who, or what, is changing? Psychosis 2018, 10, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbride, M.; Byrne, R.; Price, J.; Wood, L.; Barratt, S.; Welford, M.; Morrison, A.P. Exploring service users’ perceptions of cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis: A user led study. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2013, 41, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukla, M.; Arellano-Bravo, C.; Lysaker, P.H. “I’d be a completely different person if I hadn’t gone to therapy”: A qualitative study of metacognitive therapy and recovery outcomes in adults with schizophrenia. Psychiatry 2022, 85, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longden, E.; Branitsky, A.; Jones, W.; Peters, S. When therapists talk to voices: Perspectives from service-users who experience auditory hallucinations. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2023, 96, 967–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysaker, P.H.; Kukla, M.; Belanger, E.; White, D.A.; Buck, K.D.; Luther, L.; Firmin, R.L.; Leonhardt, B. Individual psychotherapy and changes in self-experience in schizophrenia: A qualitative comparison of patients in metacognitively focused and supportive psychotherapy. Psychiatry 2015, 78, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauritz, M.; Goossens, P.; Jongedijk, R.; Vermeulen, H.; van Gaal, B. Investigating the efficacy and experiences with narrative exposure therapy in severe mentally ill patients with comorbid post-traumatic stress disorder receiving flexible assertive community treatment: A mixed methods study. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 804491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messari, S.; Hallam, R. CBT for psychosis: A qualitative analysis of clients’ experiences. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 42, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, N.; Lotter, C.; van Staden, W. Patient reflections on individual music therapy for a major depressive disorder or acute phase schizophrenia spectrum disorder. J. Music Ther. 2020, 57, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnackenberg, J.; Fleming, M.; Martin, C.R. Experience focused counselling with voice hearers as a recovery-focused approach: A qualitative thematic inquiry. Am. J. Psychiatr. Rehabil. 2019, 22, 125–146. [Google Scholar]

- Solli, H.P.; Rolvsjord, R. “The opposite of treatment”: A qualitative study of how patients diagnosed with psychosis experience music therapy. Nord. J. Music Ther. 2015, 24, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, P.J.; Perry, A.; Hutton, P.; Tan, R.; Fisher, N.; Focone, C.; Griffiths, D.; Seddon, C. Cognitive analytic therapy for psychosis: A case series. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2019, 92, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, J.; Simpson, K.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Bendall, S. Distress, psychotic symptom exacerbation, and relief in reaction to talking about trauma in the context of beneficial trauma therapy: Perspectives from young people with post-traumatic stress disorder and first episode psychosis. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2017, 45, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, J.; Simpson, K.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Bendall, S. Talking about trauma in therapy: Perspectives from young people with post-traumatic stress symptoms and first episode psychosis. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2019, 13, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, H.; Garety, P.; Jolley, S.; Fornells-Ambrojo, M.; Kuipers, E.; Onwumere, J.; Woodall, A.; Craig, T. Training frontline mental health staff to deliver “low intensity” psychological therapy for psychosis: A qualitative analysis of therapist and service user views on the therapy and its future implementation. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2015, 43, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lysaker, P.H.; Holm, T.; Kukla, M.; Wiesepape, C.; Faith, L.; Musselman, A.; Lysaker, J.T. Psychosis and the challenges to narrative identity and the good life: Advances from research on the integrated model of metacognition. J. Res. Pers. 2022, 100, 104267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson-Ohayon, I.; Arnon-Ribenfeld, N.; Hamm, J.A.; Lysaker, P.H. Agency before action: The application of behavioral activation in psychotherapy with persons with psychosis. Psychotherapy 2017, 54, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruchlewska, A.; Kamperman, A.M.; van der Gaag, M.; Wierdsma, A.I.; Mulder, N.C. Working alliance in patients with severe mental illness who need a crisis intervention plan. Commun. Ment. Health J. 2016, 52, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igra, L.; Lavidor, M.; Atzil-Slonim, D.; Arnon-Ribenfeld, N.; de Jong, S.; Hasson-Ohayon, I. A meta-analysis of client-therapist perspectives on the therapeutic alliance: Examining the moderating role of type of measurement and diagnosis. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, M.; Bedi, R.P. Gaining perspective: How men describe incidents damaging the therapeutic alliance. Psychol. Men. Masc. 2015, 16, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavi-Rotenberg, A.; Bar-Kalifa, E.; de Jong, S.; Igra, L.; Lysaker, P.H.; Hasson-Ohayon, I. Elements that enhance therapeutic alliance and short-term outcomes in metacognitive reflection and insight therapy: A session-by-session assessment. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2020, 43, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timulak, L.; Keogh, D. The client’s perspective on (experiences of) psychotherapy: A practice friendly review. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 73, 1556–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, C.; Solli, H.P.; Krüger, V.; Lie, S.A. Dose–response relationship in music therapy for people with serious mental disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, T.M.; Jung, E.; Wiesjahn, M.; Schlier, B. What is the minimal dose of cognitive behavior therapy for psychosis? An approximation using repeated assessments over 45 sessions. Eur. Psychiatry 2016, 38, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecomte, T.; Lecomte, C. Are we there yet? Commentary on special issue on psychotherapy integration for individuals with psychosis. J. Psychother. Integr. 2012, 22, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysaker, P.H.; Roe, D. The processes of recovery from schizophrenia: The emergent role of integrative psychotherapy, recent developments, and new directions. J. Psychother. Integr. 2012, 22, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumley, A.; Clark, S. Risk of arrested recovery following first episode psychosis: An integrative approach to psychotherapy. J. Psychother. Integr. 2012, 22, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, S.; Folke, S. Affect regulation and metacognition in psychotherapy of psychosis: An integrative approach. J. Psychother. Integr. 2012, 22, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson-Ohayon, I. Integrating cognitive behavioral-based therapy with an intersubjective approach: Addressing metacognitive deficits among people with schizophrenia. J. Psychother. Integr. 2012, 22, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, G.; Russo, B.; Russo, M.; Popolo, R.; Dimaggio, G. Metacognition-oriented therapy for psychosis: The case of a woman with delusional disorder and paranoid personality disorder. J. Psychother. Integr. 2012, 22, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysaker, P.H.; Buck, K.D.; Carcione, A.; Procacci, M.; Salvatore, G.; Nicolò, G.; Dimaggio, G. Addressing metacognitive capacity for self reflection in the psychotherapy for schizophrenia: A conceptual model of the key tasks and processes. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2011, 84, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillecke, T.; Nickel, A.; Bolay, H.V. Scientific perspectives on music therapy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1060, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamm, J.A.; Ridenour, J.M.; Hillis, J.D.; Neal, D.W.; Lysaker, P.H. Fostering intersubjectivity in the psychotherapy of psychosis: Accepting and challenging fragmentation. J. Psychother. Integr. 2022, 32, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnicott, D.W. Playing and Reality, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, D.; Lysaker, P.H. Meaning, recovery, and psychotherapy in light of the art of jazz. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2023, 46, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, L.; Shahar, G.; Lawless, M.S.; Sells, D.; Tondora, J. Play, pleasure, and other positive life events: “Non-Specific” factors in recovery from mental illness. Psychiatry 2006, 69, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, M.J.; Ogles, B.M. Common factors: Post hoc explanation or empirically based therapy approach? Psychotherapy 2014, 51, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wampold, B.E. How important are the common factors in psychotherapy? An update. World Psychiatry 2015, 14, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lysaker, P.; Yanos, P.T.; Roe, D. The role of insight in the process of recovery from schizophrenia: A review of three views. Psychosis 2009, 1, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman-Taylor, K.; Bentall, R. Cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis: The end of the line or time for a new approach? Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2023, 97, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).