The Effect of the COVID Pandemic on Clinical Psychology Research: A Bibliometric Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- I.

- Number (and percentage) of research articles related to men and to women for each year. This value will allow us to observe any gender disparities in the amount of research conducted on men and women, and how such disparities might have changed across the years we examined. Conventional statistics can be used to assess changes in values over time (e.g., ANOVA, regression, etc.) or to assess changes in distributions (e.g., Chi-square).

- II.

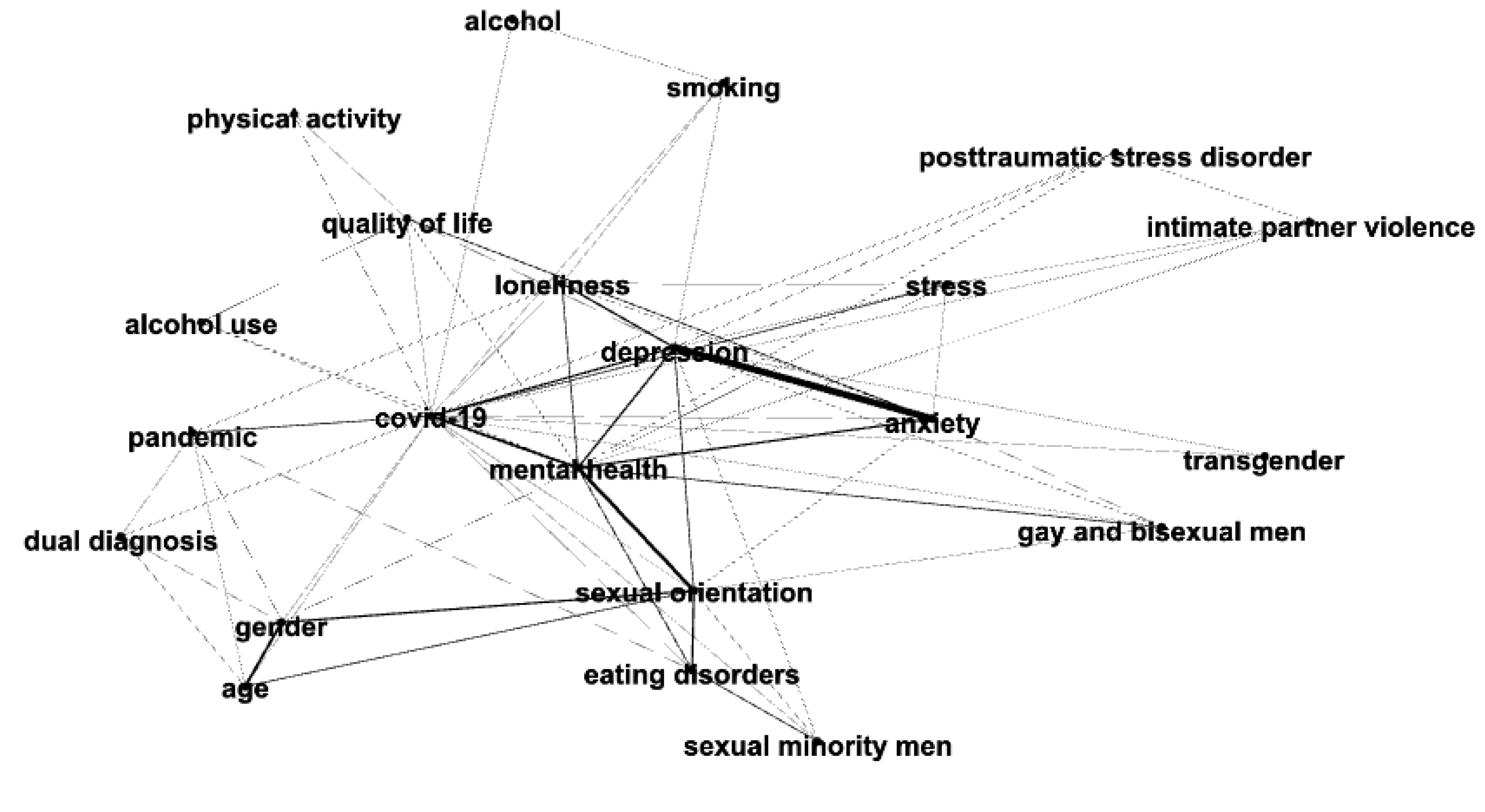

- Networks of co-occurring author-provided keywords. The author-provided keywords (henceforth “keywords”) were extracted from the Web of Science (WoS) records. Networks were created for the keywords that co-occurred each year for men and women. Nodes in the networks represented the keywords, and connections were placed between terms that co-occurred. To reduce the number of idiosyncratic terms and increase the interpretability of the visualizations, only terms that (co-)occurred more than x times per year were included in each network. The value of x was set to 3 for the men and mental health keyword networks and to 6 for the women and mental health keyword networks to account for the nearly 2 times the number of publications on women and mental health compared to men and mental health. This resulted in the top ~1% most frequently occurring keywords being examined for both men and women. The visualization and network analysis of keywords enables us to determine at the macro-level if there are patterns or trends in research topics related to mental health issues in men and women that may be present/absent. By comparing the networks across years, one can assess if these patterns or trends vary in prevalence for men and women over time.

- III.

- COVID-19 ego networks. Given our interest in how COVID-19 influenced research on mental health in men and women, we also created for 2020 and 2022 what is known as an ego network for the keyword “COVID-19”. An ego network (short for egocentric network) is a type of network that includes a single node (an “ego”) and the nodes that are directly connected to it (called “alters”), allowing us to “zoom in” on a specified node. In the present case, the ego network would show which keywords were connected to “COVID-19” for the research on men and women published in 2020 and 2022. Visualizing the ego networks for the COVID-19 keyword enables us to focus on the micro-level to consider how this global health emergency directly influenced specific research topics related to mental health issues in men and women.

- IV.

- Measures of Centrality. Measures of centrality are commonly used in network science to identify “important” nodes in a network, or nodes that facilitate or inhibit the flow of information/gossip/goods/disease in a network [27]. There are several measures of centrality [28], but two that are most useful for the keyword co-occurrence networks in the present study are degree centrality and closeness centrality. Degree centrality is the simplest measure of centrality, and refers to the number of connections incident to a node (for a more formal definition, see [27]). In the present case, degree centrality measures how many keywords co-occur with a given keyword. Nodes with many connections are considered more “important” than nodes with few (or no) connections. Closeness centrality refers to the number of connections it takes (on average) to go via the shortest path from a given node to all other nodes in the network (for a more formal definition, see [29]). If few connections (on average) must be traversed to get from node x to all the other nodes in a network, then that node is said to be close to all the other nodes in the network and would be considered more “important” than a node that is (on average) far from all the other nodes in the network (i.e., requiring the traversal of many connections on average). Measures of centrality tend to be correlated (though not perfectly).

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov) (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- World Health Organization. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-pandemic (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- The Coronavirus Tracker. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Voltmer, K.; von Salisch, M. Longitudinal prediction of primary school children’s COVID-related future anxiety in the second year of the pandemic in Germany. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0302065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, M.; Glatz, T.; Mall, M.A.; Seybold, J.; Kurth, T.; Mockenhaupt, F.P.; Theuring, S. Health-related quality of life and impact of socioeconomic status among primary and secondary school students after the third COVID-19 wave in Berlin, Germany. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0302995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bautista-Arredondo, L.F.; Muñoz-Rocha, T.V.; Figueroa, J.L.; Téllez-Rojo, M.M.; Torres-Olascoaga, L.A.; Cantoral, A.; Arboleda-Merino, L.; Leung, C.; Peterson, K.E.; Lamadrid-Figueroa, H. A surge in food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic in a cohort in Mexico City. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vameghi, M.; Saatchi, M.; Bahrami, G.; Soleimani, F.; Takaffoli, M. How did we protect children against COVID-19 in Iran? Prevalence of COVID-19 and vaccination in the socio-economic context of COVID-19 epidemic. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omale, U.I.; Ikegwuonu, C.O.; Nkwo, G.E.; Nwali, U.I.A.; Nnachi, O.O.; Ukpabi, O.O.; Okeke, I.M.; Ewah, R.L.; Iyare, O.; Amuzie, C.I.; et al. COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccination experiences and perceptions among health workers during the pandemic in Ebonyi state, Nigeria: An analytical cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, S.; Singh, L.; Alam, U.; Sharma, S.; Saroj, S.K.; Zaman, K.; Usman, M.; Kant, R.; Chaturvedi, H.K. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among adults in India: A primary study based on health behavior theories and 5C psychological antecedents model. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0294480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malkowski, O.S.; Townsend, N.P.; Kelson, M.J.; Foster, C.E.M.; Western, M.J. Socio-economic inequalities in the breadth of internet use before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among older adults in England. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, T.P.; Gebreamlak, T.W.; Gebremeskel, T.T.; Adde, B.L.; Abie, A.S.; Elias, B.P.; Argaw, A.M.; Tenaw, A.A.; Belay, B.M. Determinants of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome among hospitalized severe COVID-19 patients: A 2-year follow-up study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, E.J.D.; Conaghan, P.G.; Henderson, M.; Hulme, C.; Kingsbury, S.R.; Munyombwe, T.; West, R.; Martin, A. Long-term health conditions and UK labour market outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0302746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Maqbali, M.; Alsayed, A.; Hughes, C.; Hacker, E.; Dickens, G.L. Stress, anxiety, depression and sleep disturbance among healthcare professional during the COVID-19 pandemic: An umbrella review of 72 meta-analyses. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0302597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, M.Z.; Islam, M.S.; Kundu, L.R.; Islam, U.S.; Banik, R.; Pardhan, S. Patterns of eating behaviors, physical activity, and lifestyle modifications among Bangladeshi adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0302571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Yin, Y.; Myers, K.R.; Lakhani, K.R.; Wang, D. Potentially long-lasting effects of the pandemic on scientists. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, S.; Chan, A.Y.; Diaz Peralta, P.; Jin, L.; Nunes, C.R.P.; Bell, M.L. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on scientists’ productivity in science, technology, engineering, mathematics (STEM), and medicine fields. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortunato, S.; Bergstrom, C.T.; Börner, K.; Evans, J.A.; Helbing, D.; Milojević, S.; Petersen, A.M.; Radicchi, F.; Sinatra, R.; Uzzi, B.; et al. Science of science. Science 2018, 359, eaao0185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, Y.; Vitevitch, M.S. Using network analyses to examine the extent to which and in what ways psychology is multidisciplinary. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyack, K.W.; Klavans, R.; Börner, K. Mapping the backbone of science. Scientometrics 2005, 64, 351–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitevitch, M.S. Speech, Language, and Hearing in the 21st Century: A Bibliometric Review of JSLHR from 2001 to 2021. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2023, 66, 3428–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, D.D.; Silva, A.N.d. The Mental Health Impacts of a Pandemic: A Multiaxial Conceptual Model for COVID-19. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, A.; Rabl, L.; Höge-Raisig, T.; Höfer, S. Well-Being, Mental Health, and Study Characteristics of Medical Students before and during the Pandemic. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Diaz-Granados, N.; McDermott, S.; Wang, F.; Posada-Villa, J.; Saavedra, J.; Rondon, M.B.; Desmeules, M.; Dorado, L.; Torres, Y.; Stewart, D.E. Monitoring gender equity in mental health in a low-, middle-, and high-income country in the Americas. Psychiatr. Serv. 2011, 62, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JASP Team. JASP, Version 0.16.3; Computer software, JASP Team: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgatti, S.P. Centrality and network flow. Soc. Netw. 2005, 27, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, Z.P. Is ‘distinctiveness centrality’ actually distinctive? A comment on Fronzetti Colladon and Naldi (2020). PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavelas, A. Communication Patterns in Task-Oriented Groups. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1950, 22, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, M.; Heymann, S.; Jacomy, M. Gephi: An open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. In Proceedings of the Third International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, San Jose, CA, USA, 17–20 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sakaluk, J.K.; Williams, A.J.; Kilshaw, R.E.; Rhyner, K.T. Evaluating the evidential value of empirically supported psychological treatments (ESTs): A meta-scientific review. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2019, 128, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.J.; Botanov, Y.; Kilshaw, R.E.; Wong, R.E.; Sakaluk, J.K. Potentially harmful therapies: A meta-scientific review of evidential value. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2021, 28, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.N.; Condes Moreno, E.; Villanueva, A.R.; Orquera Miranda, P.; Chiarella, P.; Bermudez, G.; Aguilera, J.F.T.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Psychological Impacts of Teaching Models on Ibero-American Educators during COVID-19. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björk, B.-C.; Solomon, D. The publishing delay in scholarly peer-reviewed journals. J. Informetr. 2013, 7, 914–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, J.; L’Heureux, T.; Lobchuk, M.; Penner, J.; Charles, L.; St Amant, O.; Ward-Griffin, C.; Anderson, S. Double-duty caregivers enduring COVID-19 pandemic to endemic: “It’s just wearing me down”. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, E. Keywords Plus: ISI’s breakthrough retrieval method. Part 1. Expanding your searching power on Current Contents on Diskette. Curr. Contents 1990, 1, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, Q.; Zheng, F.; Long, C.; Lu, Z.; Duan, Z. Comparing Keywords Plus of WOS and Author Keywords. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerasa, A.; Craig, F.; Foti, F.; Palermo, L.; Costabile, A. The impact of COVID-19 on psychologists’ practice: An Italian experience. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2022, 7, 100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saladino, V.; Algeri, D.; Auriemma, V. The Psychological and Social Impact of COVID-19: New Perspectives of Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 577684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, N.; Siew, C.S.Q. Contributions of modern network science to the cognitive sciences: Revisiting research spirals of representation and process. Proc. R. Soc. A 2020, 476, 20190825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitevitch, M.S. Network Science in Cognitive Psychology, (Edited Volume); Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom, D.; Cramer, A.O. Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbush, K.T.; Siew, C.S.Q.; Vitevitch, M.S. Application of Network Analysis to Identify Interactive Systems of Eating Disorder Psychopathology. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 2667–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stella, M. Cognitive Network Science for Understanding Online Social Cognitions: A Brief Review. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2021, 14, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, M.; Vitevitch, M.S.; Botta, F. Cognitive Networks Extract Insights on COVID-19 Vaccines from English and Italian Popular Tweets: Anticipation, Logistics, Conspiracy and Loss of Trust. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2022, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Years | Men | Women | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 196 (35.4%) | 357 (64.6%) | 553 |

| 2018 | 225 (34.8%) | 422 (65.2%) | 647 |

| 2020 | 294 (32.6%) | 607 (67.4%) | 901 |

| 2022 | 295 (31.5%) | 642 (68.5%) | 937 |

| Total | 1010 | 2028 | 3038 |

| Common Keywords | Men Keywords | Women Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| anorexia nervosa; anxiety; depression; eating disorders; epidemiology; gender; hiv; intimate partner violence; mental health; military sexual trauma; posttraumatic stress disorder; ptsd; stress; trauma | adolescents; aggression; aging; alcohol; antipsychotics; bisexual; coping; disclosure; emergency department; gay; gay and bisexual men; gender differences; hiv prevention; hiv/aids; lesbian; masculinity; men; men who have sex with men; msm; military; mindfulness; minority stress; mood disorders; psychosis; risk factors; schizophrenia; screening; sex differences; sexual behavior; sexual orientation; sexual risk behavior; stigma; substance use; treatment | binge eating; binge eating disorder; borderline personality disorder; bulimia nervosa; parenting; postpartum depression; pregnancy; resilience; women |

| Common Keywords | Men Keywords | Women Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| anxiety; body image; depression; disordered eating; gender; gender differences; hiv; mental health; psychological distress; sexual orientation; substance use; trauma; treatment; veterans; wellbeing; women | adolescence; adolescent; african americans; assessment; bisexual; coping; depressive symptoms; disclosure; discrimination; ecological momentary assessment; gay; gay and bisexual men; gay men; gender dysphoria; gender nonconformity; help seeking; hiv prevention; hiv risk; internalized homophobia; intervention; lesbian; longitudinal; marijuana; masculinity; measurement invariance; men; men who have sex with men; msm; methamphetamine; minority stress; psychosis; sex; sexual identity; sexual minority; stigma; transgender; youth | anorexia nervosa; borderline personality disorder; domestic violence; eating disorders; emotion regulation; intimate partner violence; mindfulness; obesity; posttraumatic stress disorder; ptsd; postpartum; postpartum depression; pregnancy; primary care; quality of life; risk factors; stress; systematic review; transgender |

| Common Keywords | Men Keywords | Women Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| adolescents; anxiety; bisexual; body image; couples; COVID-19; depression; discrimination; dsm; eating disorders; fear; gender; gender differences; health; help seeking; hiv; intimate partner violence; mental health; meta-analysis; mindfulness; minority stress; posttraumatic stress disorder; ptsd; resilience; self-compassion; sexual minority; sexual orientation; social support; stigma; stress; substance use; suicidal ideation; suicide; transgender; trauma; treatment; veterans; well-being | african american; alcohol; alcohol use; cbt; co-occurring disorders; college; college students; comorbidity; coping; cross-cultural; evidence-based treatment; gay; gay and bisexual men; gay men; gender identity; health psychology; health-related quality of life; help seeking; hiv prevention; identity; internalized homophobia; intersectionality; lesbian; loneliness; longitudinal study; masculinity; measurement invariance; men; men who have sex with men/msm; methamphetamine; non-binary; peer support; prevalence; psychosis; psychotherapy; risk; risk assessment; rumination; sexual and gender minorities; sexual arousal; sexual function; sexual functioning; sexuality; sexually transmitted infections; social anxiety; south africa; substance use disorders; syndemic | anorexia nervosa; assessment; borderline personality disorder; bulimia nervosa; domestic violence; eating disorder; emotion regulation; epidemiology; military sexual trauma; parenting; perinatal; postpartum depression; posttraumatic stress; pregnancy; quality of life; race; sexual abuse; sexual assault; sleep; systematic review; trauma; treatment; veterans; well-being; women; women’s health |

| Common Keywords | Men Keywords | Women Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| age; alcohol; anxiety; assessment; bisexual; body image; college students; comorbidity; COVID-19; depression; depressive symptoms; discrimination; eating disorders; gender; gender differences; hiv; intersectionality; intimate partner violence; loneliness; measurement invariance; mental health; meta-analysis; military; military sexual trauma; mindfulness; pandemic; physical activity; posttraumatic stress disorder; ptsd; psychometrics; psychopathology; psychotherapy; race; resilience; sexual orientation; stigma; stress; substance use; suicide; transgender; trauma; treatment; veteran/veterans; well-being; women | adolescents; aging; alcohol use; barriers; dual diagnosis; emerging adults; factor analysis; gay; gay and bisexual men; gay men; help-seeking; homelessness; internalized homonegativity; lgbtq; masculinity; men; men who have sex with men; minority stress; prevalence; psychometric properties; psychosis; quality of life; recovery; religion; schizophrenia; self-harm; sex; sexual health; sexual minority men; smoking; systematic review | adverse childhood experiences; anorexia nervosa; binge eating; black women; body dissatisfaction; borderline personality disorder; bulimia nervosa; disordered eating; domestic violence; emotion dysregulation; emotion regulation; epidemiology; fmri; health; intervention; latent class analysis; longitudinal; obesity; opioid use disorder; perinatal; postpartum; pregnancy; qualitative; quality of life; screening; self-compassion; self-esteem; sexual assault; social support; substance use disorder; thematic analysis |

| Degree Centrality | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | ||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women |

| sexual orientation; mental health; epidemiology; depression; hiv | depression; intimate partner violence; pregnancy; mental health; anorexia nervosa | mental health; sexual orientation; depression; gender; discrimination | depression; mental health; women; anxiety; gender | sexual orientation; mental health; depression; gender; stigma; COVID-19 (62) | depression; mental health; trauma; intimate partner violence; women; COVID-19 (22) | mental health; sexual orientation; depression; COVID-19; eating disorders | mental health; depression; COVID-19; eating disorders; intimate partner violence |

| Closeness Centrality | |||||||

| 2015 | 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | ||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women |

| antipsychotics; schizophrenia; sexual orientation; epidemiology; mental health | intimate partner violence; depression; pregnancy; mental health; anorexia nervosa | sexual orientation; mental health; depression; gender; discrimination | depression; mental health; women; gender; substance use | help seeking; risk assessment; sexual orientation; mental health; depression; COVID-19 (72) | depression; mental health; trauma; intimate partner violence; anxiety; COVID-19 (24) | mental health; sexual orientation; depression; COVID-19; eating disorders | mental health; depression; COVID-19; intimate partner violence; eating disorders |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anders, J.; Vitevitch, M.S. The Effect of the COVID Pandemic on Clinical Psychology Research: A Bibliometric Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060463

Anders J, Vitevitch MS. The Effect of the COVID Pandemic on Clinical Psychology Research: A Bibliometric Analysis. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(6):463. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060463

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnders, Jordan, and Michael S. Vitevitch. 2024. "The Effect of the COVID Pandemic on Clinical Psychology Research: A Bibliometric Analysis" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 6: 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060463

APA StyleAnders, J., & Vitevitch, M. S. (2024). The Effect of the COVID Pandemic on Clinical Psychology Research: A Bibliometric Analysis. Behavioral Sciences, 14(6), 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060463