The Influence of Cognitive and Emotional Factors on Social Media Users’ Information-Sharing Behaviours during Crises: The Moderating Role of the Construal Level and the Mediating Role of the Emotional Response

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Foundation

2.1. User Information-Sharing Behaviours in a Crisis

2.2. Heuristic–Systematic Model

2.3. Construal Level Theory

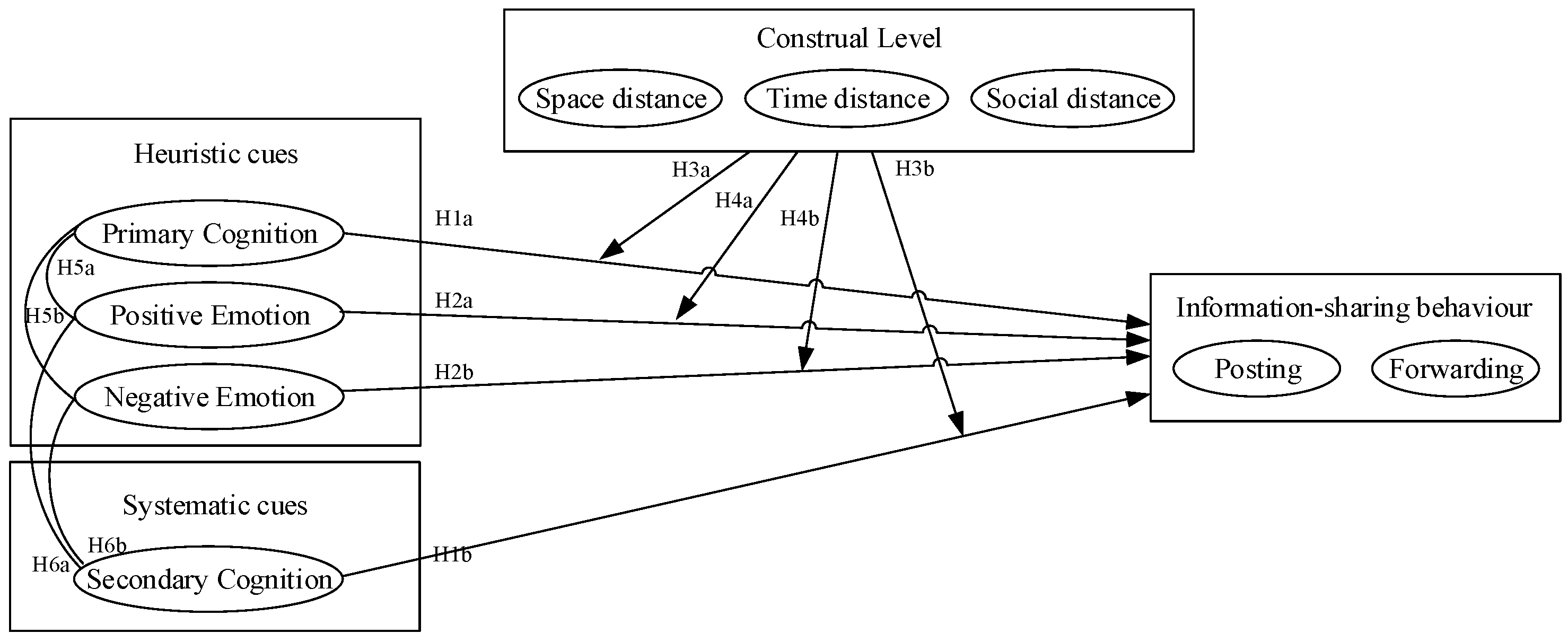

3. Research Model and Hypotheses Development

3.1. Theoretical Model

3.2. Hypotheses’ Development

3.2.1. The Influence of Cognitive Appraisal on Information-Sharing Behaviours

3.2.2. The Influence of Emotional Responses on Information-Sharing Behaviours

3.2.3. The Moderating Effect of the Construal Level

3.2.4. The Mediating Effect of Emotional Responses

4. Research Design

4.1. Sample Selection and Data Source

4.2. Variable Design

5. Data Analysis

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

5.2. Hypothesis Test

5.2.1. Hypothesis Test Result

5.2.2. The Main Effects of Cognitive Appraisal and Emotional Responses on Information-Sharing Behaviours

5.2.3. The Moderating Effect Test of the Construal Level

5.2.4. The Mediating Effect Test of the Emotional Response

6. Discussion

6.1. Discussion

6.2. Theoretical Contribution

6.3. Practical Implications

6.4. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, Y.; Qiu, J.; Jin, C.; Gu, W.; Dou, S. The influence of psychological language words contained in microblogs on dissemination behaviour in emergency situations-mediating effects of emotional responses. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2022, 41, 1337–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yossatorn, Y.; Binali, T.; Weng, C.; Chu, R.J. Investigating the Relationships Among LINE Users’ Concerns, Motivations for Information Sharing Intention and Information Sharing Behavior. SAGE Open 2023, 13, 21582440231192951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-N.; Hou, Y.-Z.; Wang, J.; Fu, P.; Xia, C.-Z. How does leaders’ information-sharing behavior affect subordinates’ taking charge behavior in public sector? A moderated mediation effect. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 938762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumaedi, S.; Sumardjo; Saleh, A.; Syukri, A.F. Factors influencing millennials’ online healthy food information-sharing behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 2772–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Kuang, W. Exploring Influence Factors of WeChat Users’ Health Information Sharing Behavior: Based on an Integrated Model of TPB, UGT and SCT. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 2021, 37, 1243–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Wan, M.; Li, Z. Understanding the Health Information Sharing Behavior of Social Media Users. J. Organ. End User Comput. 2021, 33, 180–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, L.T.; Thanh, P.T. Exposure to risk communication, compliance with preventive measures and information-sharing behavior among students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Kybernetes 2023, 52, 2597–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballandies, M.C. To Incentivize or Not: Impact of Blockchain-Based Cryptoeconomic Tokens on Human Information Sharing Behavior. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 74111–74130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, F.; Wang, X.; Yu, G. Determinants of debunking information sharing behaviour in social media users: Perspective of persuasive cues. Internet Res. 2023; manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cheng, Z. Users’ unverified information-sharing behavior on social media: The role of reasoned and social reactive pathways. Acta Psychol. 2024, 245, 104215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Qiu, J.; Gu, W.; Ge, Y. The Dynamic Effects of Perceptions of Dread Risk and Unknown Risk on SNS Sharing Behavior During EID Events: Do Crisis Stages Matter? J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2020, 21, 545–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, B. Research on the influencing factors of native advertising forwarding volume: Based on the perspective of infor-mation source characteristics and sharing reward. Collect. Essays Financ. Econ. 2022, 9, 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Lappas, T.; Sabnis, G. The Importance of Interactions Between Content Characteristics and Creator Characteristics for Studying Virality in Social Media. Inform. Syst. Res. 2020, 31, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.; Zhu, D. A model and simulation of the emotional contagion of netizens in the process of rumor refutation. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, S.; Wu, D. Research on the Construction of Multilingual User Information Sharing Behavior Process Model from the Per-spective of Cross-cultural Communication. Inf. Stud. Theory Appl. 2023, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chaiken, S.; Maheswaran, D. Heuristic processing can bias systematic processing: Effects of source credibility, argument ambiguity, and task importance on attitude judgment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon-Wilson, S. Consumption practices during the COVID-19 crisis. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Lai, K.K.; Hu, P.; Chen, G. Factors dominating individual information disseminating behavior on social networking sites. Inform. Technol. Manag. 2018, 19, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.; Taflanidis, A.A.; Kyprioti, A.P.; Zhang, J. Adaptive multi-fidelity Monte Carlo for real-time probabilistic storm surge predictions. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 247, 109994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, H.; Oh, H.J.; Hove, T. Differential effects of digital media platforms on climate change risk information-sharing intention: A moderated mediation model. Risk Anal. 2024; manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Schaik, P.; Jansen, J.; Onibokun, J.; Camp, J.; Kusev, P. Security and privacy in online social networking: Risk perceptions and precautionary behaviour. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 78, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tan, H.; Yin, C.; Shi, D. Does an image facilitate the sharing of negative news on social media? An experimental investigation. Libr. Inform. Sci. Res. 2021, 43, 101120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apuke, O.D.; Omar, B. Fake news and COVID-19: Modelling the predictors of fake news sharing among social media users. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 56, 101475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennebaker, J.W.; Mehl, M.R.; Niederhoffer, K.G. Psychological Aspects of Natural Language Use: Our Words, Our Selves. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 547–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flemotomos, N.; Martinez, V.R.; Chen, Z.; Singla, K.; Ardulov, V.; Peri, R.; Caperton, D.D.; Gibson, J.; Tanana, M.J.; Georgiou, P.; et al. Automated evaluation of psychotherapy skills using speech and language technologies. Behav. Res. Methods 2022, 54, 690–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plamadeala, C.; Tileaga, C. The Moral Career of a Suspected Legionary: Psychological Language in the Securitate Archives. East Eur. Politics Soc. Cult. 2022, 36, 1133–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Sun, Z.; Wei, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, G.; Chen, L. PS-GCN: Psycholinguistic graph and sentiment semantic fused graph convolutional networks for personality detection. Connect. Sci. 2024, 36, 2295820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworakowski, O.; Meier, T.; Mehl, M.R.; Pennebaker, J.W.; Boyd, R.L.; Horn, A.B. Comparing the language style of heads of state in the US, UK, Germany and Switzerland during COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Qi, J.; Fu, X.; Cai, M. Research on connective action persuasion strategies in the context of social crisis: Text analysis of user-generated contents in social media. J. Ind. Eng. Eng. Manag. 2021, 35, 90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, C.M.; Thadani, D.R. The impact of electronic word-of-mouth communication: A literature analysis and integrative model. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 54, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Wang, A.; Wang, C.; Ma, Q. How do consumers perceive and process online overall vs. individual text-based reviews? Behavioral and eye-tracking evidence. Inform. Manag. 2023, 60, 103795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Xi, W.; Xu, F.Z.; Wu, R. Deconstructing consumers’ low-carbon tourism promotion preference and its consequences: A heuristic-systematic model. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 57, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, J.; Liu, J. The role of audience favorability in processing (un)familiar messages: A heuristic-systematic model perspective. Hum. Commun. Res. 2023, 49, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, H.-Y.; Hu, Y.; Lee, N.; Tsai, H.-T. Exploring online consumer review-management response dynamics: A heuristic-systematic perspective. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 177, 114087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, V.; Kordrostami, E. Price sensitivity and online shopping behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Consum. Mark. 2023, 40, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Chen, A.; Zeng, J. Impact of information processing on purchase intention in new energy vehicle product harm crises. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2024, 32, e12519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Guo, L.; Lu, H. Pro-environmental behavior: A perspective of dual system theory of decision making. Psychol. Res. 2019, 12, 154–161. [Google Scholar]

- Sharples, L.; Fletcher-Brown, J.; Sit, K.; Nieto-Garcia, M. Exploring crisis communications during a pandemic from a cruise marketing managers perspective: An application of construal level theory. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 3175–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Yang, Q.; Gong, X. Impulsive Social Shopping in Social Commerce Platforms: The Role of Perceived Proximity. Inform. Syst. Front. 2023, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.; Chang, Y.; Kim, B.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, S.-C. Influence of Personal Innovativeness and Different Sequences of Data Presentation on Evaluations of Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Int. J. Human–Comput. Interact. 2023, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Moon, M.J.; Park, S. Impact of public information campaign on citizen behaviors: Vignette experimental study on recycling program in South Korea. Rev. Policy Res. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, M.K.; Colby, H.; Saxton, T.; Pasumarti, V. Why or How? the impact of Construal-Level Theory on vaccine message receptivity. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 172, 114436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, B.; Gong, J.; Hai, M. The influence of construal levels on the judgment of unfair event: The moderating effect of fairness sensitivity. J. Psychol. Sci. 2023, 46, 881–888. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, W.; Zhao, X. Measurement and empirical research on psychological distance perception intensity of network public opinion users’ communication behavior. Inform. Stud. Theory Appl. 2024, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanova, M.; Cosme, D.; Doré, B.; Kang, Y.; Stanoi, O.; Cooper, N.; Helion, C.; Lomax, S.; McGowan, A.L.; Boyd, Z.M.; et al. Psychological distance intervention reminders reduce alcohol consumption frequency in daily life. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brügger, A. Understanding the psychological distance of climate change: The limitations of construal level theory and suggestions for alternative theoretical perspectives. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2020, 60, 102023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, L.; Bui, H.T. Psychologically gaining through losing: A metaphor analysis. J. Manag. Psychol. 2024, 39, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, J. Cognitive Frames of Poverty and Tension Handling in Base-of-the-Pyramid Business Models. Bus. Soc. 2022, 61, 2070–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.; Martínez, R.; Briñol, P.; Petty, R.E. Improving attitudes towards minority groups by thinking about the thoughts and meta-cognitions of their members. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 53, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Zhang, N.; Mou, J.; Zhang, Q. Fueling user engagement in virtual CSR co-creation with mental simulation: A cognitive appraisal perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 172, 114438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Zhang, L. Adoption of green innovations in project-based firms: An integrating view of cognitive and emotional framing. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 279, 111612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.S. Thoughts on the Relations Between Emotion and Cognition. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeter, C.; Walters, G.; Mair, J. Identifying appropriate service recovery strategies in the event of a natural disaster. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Z.; Dong, X. Monkeypox outbreak: Psychological distance, risk perception, and support for risk mitigation. J. Health Psychol. 2023, 29, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; Zhu, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L. Research on supervisor idea rejection, discrete emotion and Approach-Avoidance behavior of knowledge worker—Based on perspective of cognitive appraisal theory of emotions. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2023, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H.; Tu, L.; Guo, Y.; Chen, J. The influence of cross-platform and spread sources on emotional information spreading in the 2E-SIR two-layer network. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 165, 112801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Trott, S.; Sahadev, S.; Singh, R. Emotions and consumer behaviour: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 2396–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jin, Y.; Reber, B.H. Assessing an organizational crisis at the construal level: How psychological distance impacts publics’ crisis responses. J. Commun. Manag. 2020, 24, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, J.; Filieri, R.; Xiao, J.; Han, Q.; Zhu, B.; Wang, T. Product information and green consumption: An integrated perspective of regulatory focus, self-construal, and temporal distance. Inform. Manag. 2023, 60, 103746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Fu, J.; Lai, J.; Sun, L.; Zhou, C.; Li, W.; Jian, B.; Deng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Z.; et al. Construction of an Emotional Lexicon of Patients With Breast Cancer: Development and Sentiment Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e44897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, F.; Jin, X.; Gu, S. Legitimization of business model innovation from the perspective of evaluator categorization: A case study of the emergence of online car-hailing. J. Manag. World 2023, 8, 114–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ashokkumar, A.; Pennebaker, J.W. Tracking group identity through natural language within groups. PNAS Nexus 2022, 1, pgac022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, K.A.; Shroff, A.; Nook, E.C.; Schleider, J.L. Linguistic distancing predicts response to a digital single-session intervention for adolescent depression. Behav. Res. Ther. 2022, 159, 104220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Z.; Fang, J.; Xie, J.; Ouyang, J. Methodological Research on Mediation Effects in China’s Mainland. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 30, 1692–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Gong, Y.; Lu, Y.; Chau, P.Y. How mindfulness decreases cyberloafing at work: A dual-system theory perspective. Eur. J. Inform. Syst. 2022, 32, 841–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Milkman, K.L. What Makes Online Content Viral? J. Mark. Res. 2011, 49, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R.M. Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. J. Commun. 1993, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weismueller, J.; Harrigan, P.; Coussement, K.; Tessitore, T. What makes people share political content on social media? The role of emotion, authority and ideology. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 129, 107150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, J. Psychological distance asymmetry: The spatial dimension vs. other dimensions. J. Consum. Psychol. 2009, 19, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Measurement | LIWC Words | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary cognitive appraisal (PCA) | Words that reflect dimensions such as those which are sensory, perceptual, etc. | Percept | [50] |

| Secondary cognitive appraisal (SCA) | Words that reflect dimensions such as insight, cause, etc. | CogMech | |

| Positive emotional response (PER) | Words that reflect positive emotions such as happiness, blessing, etc. | PosEmo | [52] |

| Negative emotional response (NER) | Word that reflects negative emotions such as sadness, anger, etc. | NegEmo | |

| Space distance (SP_PD) | Words that reflect the location of the event. | Space | [46] |

| Time distance (TM_PD) | Words that reflect the time of the event. | Time | |

| Social distance (SC_PD) | Words that reflect personal concerns. | I | |

| Posting behaviour (PST) | The number of Weibo posts. | / | [1] |

| Forwarding behaviour (FWD) | The number of Weibo retweets. | / | |

| Ratio of male to female users (RMF) | Control variable: ratio of male to female users. | ||

| Ratio of institutional to individual users (RII) | Control variable: proportion of institutional individual users. | ||

| Variables | PCA | SCA | PER | NER | SP_PD | TM_PD | SC_PD | RMF | RII | PST | FWD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | 1 | ||||||||||

| SCA | 0.973 | 1 | |||||||||

| PER | 0.945 | 0.957 | 1 | ||||||||

| NER | 0.938 | 0.949 | 0.942 | 1 | |||||||

| SP_PD | −0.870 | −0.904 | −0.857 | −0.833 | 1 | ||||||

| TM_PD | −0.796 | −0.840 | −0.770 | −0.778 | 0.922 | 1 | |||||

| SC_PD | −0.336 | −0.374 | −0.305 | −0.313 | 0.480 | 0.458 | 1 | ||||

| RMF | −0.014 | −0.016 | −0.024 | 0.008 | −0.025 | 0.023 | 0.221 | 1 | |||

| RII | 0.467 | 0.482 | 0.438 | 0.462 | −0.485 | −0.449 | −0.212 | 0.229 | 1 | ||

| PST | 0.969 | 0.9856 | 0.972 | 0.955 | −0.889 | −0.807 | −0.334 | 0.009 | 0.504 | 1 | |

| FWD | 0.832 | 0.846 | 0.827 | 0.823 | −0.756 | −0.679 | −0.309 | 0.042 | 0.500 | 0.859 | 1 |

| Min | 0 | 0.693 | 0 | 0 | 0.110 | 0.446 | 0.169 | 0 | 0 | 0.693 | 0 |

| Max | 6.909 | 9.240 | 8.212 | 6.759 | 0.621 | 1.899 | 100,000,000 | 100 | 75 | 7.742 | 9.835 |

| Mean | 3.747 | 5.674 | 4.314 | 3.107 | 0.211 | 0.606 | 4,815,864 | 55.125 | 17.981 | 3.972 | 4.089 |

| SD | 1.456 | 1.504 | 1.526 | 1.653 | 0.075 | 0.136 | 21,400,000 | 13.122 | 14.395 | 1.512 | 2.680 |

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable: Information-Sharing Behaviour | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PST | FWD | PST | FWD | PST | FWD | PST | FWD | |||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | Model 11 | Model 12 | Model 13 | Model 14 | |

| PCA | 0.074 | 0.182 | 0.085 | ns | 0.178 | 0.033 | 0.073 | 0.048 | 0.084 | 0.091 | 0.081 | 0.07 | 0.181 | 0.057 |

| SCA | 0.527 | 0.734 | 0.516 | 0.625 | 0.736 | 0.856 | 0.541 | 0.668 | 1.035 | 0.997 | 0.533 | 0.555 | 0.723 | 0.941 |

| PER | 0.293 | 0.312 | 0.314 | 0.389 | 0.306 | 0.382 | 0.315 | 0.29 | 0.298 | 0.303 | 0.307 | 0.299 | 0.309 | 0.29 |

| NER | 0.061 | 0.189 | 0.065 | 0.025 | 0.189 | 0.284 | 0.058 | 0.043 | 0.143 | 0.145 | 0.063 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.138 |

| SP_PD | −0.026 | 1.026 | ns | 1.467 | ||||||||||

| PCA*SP_PD | −0.01 | ns | ||||||||||||

| SCA*SP_PD | −0.89 | −0.854 | ||||||||||||

| PER*SP_PD | −0.878 | −1.152 | ||||||||||||

| NER*SP_PD | ns | −0.672 | ||||||||||||

| TM_PD | 0.108 | 0.283 | 1.89 | 1.596 | ||||||||||

| PCA*TM_PD | ns | ns | ||||||||||||

| SCA*TM_PD | −0.205 | ns | ||||||||||||

| PER*TM_PD | ns | ns | ||||||||||||

| NER*TM_PD | ns | ns | ||||||||||||

| SC_PD | ns | ns | ns | ns | ||||||||||

| PCA*SC_PD | ns | ns | ||||||||||||

| SCA*SC_PD | ns | ns | ||||||||||||

| PER*SC_PD | ns | ns | ||||||||||||

| NER*SC_PD | ns | ns | ||||||||||||

| RMF | ns | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.003 |

| RII | 0.002 | 0.022 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.021 | 0.019 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.023 | 0.022 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.021 | 0.022 |

| _cons | −0.791 | −3.364 | −0.992 | 0.066 | −3.27 | −2.032 | −1.136 | −1.017 | −5.68 | −5.312 | −1.026 | −1.044 | −3.211 | −3.67 |

| Lambda | 36.881 | 2.604 | 0.893 | 0.893 | 12.662 | 6.602 | 3.579 | 3.928 | 0.335 | 4.537 | 1.712 | 2.726 | 16.739 | 1.635 |

| MSPE | 0.042 | 1.99 | 0.039 | 0.028 | 1.99 | 1.975 | 0.04 | 0.039 | 1.959 | 1.975 | 0.038 | 0.038 | 1.992 | 1.991 |

| St. dev. | 0.005 | 0.194 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.193 | 0.189 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.292 | 0.296 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.193 | 0.196 |

| Independent Variable | PER | Dependent Variable: Information-Sharing Behaviour | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PST | FWD | PST | FWD | |||||||

| Model 15 | Model 20 | Model 16 | Model 17 | Model 18 | Model 19 | Model 21 | Model 22 | Model 23 | Model 24 | |

| PCA | 0.9608 | 0.9662 | 0.4391 | 1.2468 | 0.7447 | |||||

| SCA | 0.9448 | 0.9348 | 0.6223 | 1.2457 | 0.9895 | |||||

| PER | / | / | / | 0.5065 | / | 0.6768 | / | 0.3288 | / | 0.26 |

| RMF | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | 0.0052 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| RII | ns | ns | 0.0062 | 0.0039 | 0.0099 | 0.0252 | ns | 0.0023 | 0.0057 | 0.0066 |

| _cons | 0.7133 | −1.0473 | 0.2406 | 0.0716 | −0.7614 | −2.3605 | −1.3318 | −1.019 | −3.0815 | −2.7643 |

| Lambda | 29.621 | 27.343 | 10.813 | 48.096 | 244.529 | 0.437 | 58.725 | 40.477 | 248.567 | 248.567 |

| MSPE | 0.2547 | 0.1987 | 0.136 | 0.0715 | 2.3015 | 2.032 | 0.0733 | 0.0444 | 2.1631 | 2.1459 |

| St. dev. | 0.0198 | 0.024 | 0.0117 | 0.0072 | 0.1557 | 0.1818 | 0.0073 | 0.0048 | 0.163 | 0.159 |

| Independent Variable | NER | Dependent Variable: Information-Sharing Behaviour | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PST | FWD | PST | FWD | |||||||

| Model 25 | Model 30 | Model 26 | Model 27 | Model 28 | Model 29 | Model 31 | Model 32 | Model 33 | Model 34 | |

| PCA | 1.0333 | 0.9662 | 0.6113 | 1.2468 | 0.7672 | |||||

| SCA | 1.0383 | 0.9348 | 0.7906 | 1.2457 | 1.0211 | |||||

| NER | / | / | / | 0.3423 | / | 0.4426 | / | 0.1723 | / | 0.2159 |

| RMF | ns | 0.0024 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | 0.0009 | ns | ns |

| RII | 0.0021 | ns | 0.0062 | 0.0053 | 0.0099 | 0.0068 | ns | 0.0032 | 0.0057 | 0.0056 |

| _cons | −0.8021 | −2.9147 | 0.2406 | 0.5219 | −0.7614 | −0.2824 | −1.3318 | −1.1546 | −3.0815 | −2.4756 |

| Lambda | 21.954 | 5.506 | 10.813 | 5.137 | 244.529 | 268.371 | 58.725 | 5.737 | 248.567 | 248.567 |

| MSPE | 0.3356 | 0.2751 | 0.136 | 0.0979 | 2.3015 | 2.2624 | 0.0733 | 0.0566 | 2.1631 | 2.1602 |

| St. dev. | 0.0325 | 0.0321 | 0.0117 | 0.0096 | 0.1557 | 0.167 | 0.0073 | 0.0077 | 0.163 | 0.1682 |

| Hypothesis | Results | |

|---|---|---|

| H1a | The primary cognitive appraisal contained in the information content can positively affect users’ information-sharing behaviours. | Support |

| H1b | The secondary cognitive appraisal contained in the information content can positively affect users’ information-sharing behaviours. | Support |

| H2a | The positive emotional response contained in the information content can positively affect users’ information-sharing behaviours. | Support |

| H2b | The negative emotional response contained in the information content can negatively affect users’ information-sharing behaviours. | No support |

| H3a | The construal level weakens the influence of primary cognitive appraisal on information-sharing behaviours. | Partial support |

| H3b | The construal level weakens the influence of secondary cognitive appraisal on information-sharing behaviours. | Support |

| H4a | The construal level weakens the influence of a positive emotional response on information-sharing behaviours. | Support |

| H4b | The construal level weakens the influence of a negative emotional response on information-sharing behaviours. | Partial support |

| H5a | A positive emotional response plays a mediating role between primary cognitive appraisal and information-sharing behaviours. | Partial support |

| H5b | A negative emotional response plays a mediating role between primary cognitive appraisal and information-sharing behaviours. | Partial support |

| H6a | A positive emotional response plays a mediating role between secondary cognitive appraisal and information-sharing behaviours. | Partial support |

| H6b | A negative emotional response plays a mediating role between secondary cognitive appraisal and information-sharing behaviours. | Partial support |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, Y. The Influence of Cognitive and Emotional Factors on Social Media Users’ Information-Sharing Behaviours during Crises: The Moderating Role of the Construal Level and the Mediating Role of the Emotional Response. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060495

Lu Y. The Influence of Cognitive and Emotional Factors on Social Media Users’ Information-Sharing Behaviours during Crises: The Moderating Role of the Construal Level and the Mediating Role of the Emotional Response. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(6):495. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060495

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Yanxia. 2024. "The Influence of Cognitive and Emotional Factors on Social Media Users’ Information-Sharing Behaviours during Crises: The Moderating Role of the Construal Level and the Mediating Role of the Emotional Response" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 6: 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060495