The Relationship between Maladaptive Perfectionism and Anxiety in First-Year Undergraduate Students: A Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Maladaptive Perfectionism and Anxiety

2.2. The Mediating Role of Self-Compassion

2.3. The Moderating Role of Family Support

2.4. The Present Study

3. Method

3.1. Participants

3.2. Research Tools

3.2.1. Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale—Brief

3.2.2. Anxiety Scale

3.2.3. Self-Compassion Scale

3.2.4. Family Support Questionnaire

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Deviation

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Related Analysis for Each Variable

4.3. Testing for the Mediation Effect

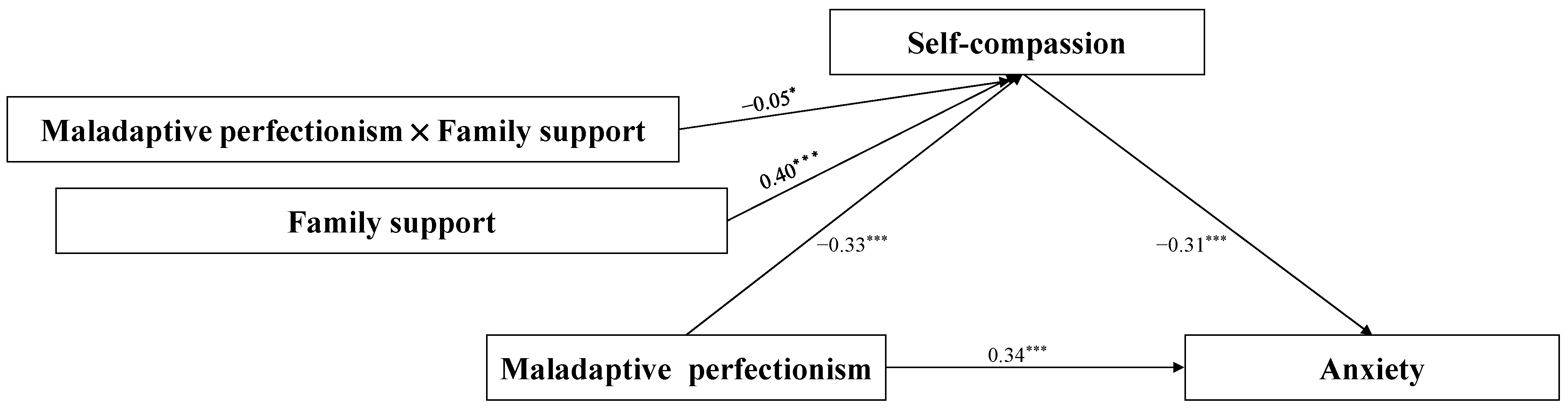

4.4. Test of the Moderated Mediation Model

5. Discussion

5.1. The Relationship between Maladaptive Perfectionism and Anxiety

5.2. The Mediating Role of Self-Compassion

5.3. The Moderating Role of Family Support

5.4. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fromme, K.; Corbin, W.R.; Kruse, M.I. Behavioral risks during the transition from high school to college. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 44, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, A.S.; Geary, P.S.; Waterman, C.K. Longitudinal study of changes in ego identity status from the freshman to the senior year at college. Dev. Psychol. 1974, 10, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoi, I.G.; Sauta, M.D.; Granieri, A. State and trait anxiety among university students: A moderated mediation model of negative affectivity, alexithymia, and housing conditions. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Bian, Q.; Song, Y.-Y.; Ren, J.-Y.; Xu, X.-Y.; Zhao, M. Prevalence and related risk factors of anxiety and depression among Chinese college freshmen. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. [Med. Sci.] 2015, 35, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Margraf, J. Less sense of control, more anxiety, and addictive social media use: Cohort trends in German university freshmen between 2019 and 2021. Curr. Res. Behav. Sci. 2023, 4, 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Ping, S.; Liu, X. Gender differences in depression, anxiety, and stress among college students: A longitudinal study from China. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 263, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, R.O.; Marten, P.; Lahart, C.; Rosenblate, R. The dimensions of perfectionism. Cogn. Ther. Res. 1990, 14, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enns, M.W.; Cox, B.J.; Clara, I. Adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism: Developmental origins and association with depression proneness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2002, 33, 921–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamachek, D.E. Psychodynamics of normal and neurotic perfectionism. Psychol. A J. Hum. Behav. 1978, 15, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, A.; Abbott, M.J. Review of the theoretical, empirical, and clinical status of adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism. Behav. Change 2013, 30, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zung, W.W. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosom. J. Consult. Liaison Psychiatry 1971, 12, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, R.O.; Heimberg, R.G.; Holt, C.S.; Mattia, J.I.; Neubauer, A.L. A comparison of two measures of perfectionism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1993, 14, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, A.M.; Frost, R.O.; DiBartolo, P.M. Development and validation of the frost multidimensional perfectionism scale–brief. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2016, 34, 620–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J.; Otto, K. Positive conceptions of perfectionism: Approaches, evidence, challenges. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, H.; Hu, C.; Wang, L. Maladaptive perfectionism and adolescent NSSI: A moderated mediation model of psychological distress and mindfulness. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 78, 1137–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Morita, N.; Zuo, Z.; Kawaida, K.; Ogai, Y.; Saito, T.; Hu, W. Maladaptive perfectionism and internet addiction among Chinese college students: A moderated mediation model of depression and gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.; Li, L.; Shi, J.; Liang, H.; Yang, X. Self-compassion mediates the perfectionism and depression link on Chinese undergraduates. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 1950960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; He, L.; Wei, M.; Du, Y.; Cheng, D. Depression and anxiety from acculturative stress: Maladaptive perfectionism as a mediator and mindfulness as a moderator. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2022, 13, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Chen, Y.-N.K. Collectivism, relations, and Chinese communication. Chin. J. Commun. 2010, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-F.; Wei, M. Perfectionism and negative mood: The mediating roles of validation from others versus self. J. Couns. Psychol. 2008, 55, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivula, N.; Hassmén, P.; Fallby, J. Self-esteem and perfectionism in elite athletes: Effects on competitive anxiety and self-confidence. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2002, 32, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.M.; Leffingwell, T.R. Cognitive strategies in sport and exercise psychology. In Exploring Sport and Exercise Psychology, 2nd ed.; Van Raalte, J.L., Brewer, B.W., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda Espejel, H.A.; Morquecho Sánchez, R.; Fernández, R.; González Hernández, J. Perfeccionismo interpersonal, miedo a fallar, y afectos en el deporte. Cuad. De Psicol. Del Deporte 2019, 19, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swee, M.B.; Olino, T.M.; Heimberg, R.G. Worry and anxiety account for unique variance in the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and depression. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2019, 48, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, A.; Carlbring, P.; Vaez, E.; Ghahfarokhi, S.A. Perfectionism and test anxiety among high-school students: The moderating role of academic hardiness. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 37, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newby, J.; Pitura, V.A.; Penney, A.M.; Klein, R.G.; Flett, G.L.; Hewitt, P.L. Neuroticism and perfectionism as predictors of social anxiety. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 106, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bong, M.; Hwang, A.; Noh, A.; Kim, S.-i. Perfectionism and motivation of adolescents in academic contexts. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 106, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nounopoulos, A.; Ashby, J.S.; Gilman, R. Coping resources, perfectionism, and academic performance among adolescents. Psychol. Sch. 2006, 43, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, S.; Strodl, E.; Sun, H. Academic stress, parental pressure, anxiety and mental health among Indian high school students. Int. J. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2015, 5, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, D.E.; Kaye, M.P.; Fifer, A.M. Cognitive links between fear of failure and perfectionism. J. Ration.-Emotive Cogn.-Behav. Ther. 2007, 25, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity 2003, 2, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inwood, E.; Ferrari, M. Mechanisms of change in the relationship between self-compassion, emotion regulation, and mental health: A systematic review. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2018, 10, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitt, A.; Oprescu, F.; Tapia, G.; Gray, M. An exploratory study of students’ weekly stress levels and sources of stress during the semester. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, N.A.; Ghosh, A.; Chang, W.-h.; Figueiredo, C.; Bachhuber, T. Career exploration among college students. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2016, 57, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzrow, M.A. The mental health needs of today’s college students: Challenges and recommendations. Naspa J. 2009, 46, 646–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, B.; Cai, T. Perceived social support as moderator of perfectionism, depression, and anxiety in college students. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2013, 41, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biskas, M.; Sirois, F.M.; Webb, T.L. Using social cognition models to understand why people, such as perfectionists, struggle to respond with self-compassion. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 61, 1160–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, A.B.; Leary, M.R. Self-Compassion, stress, and coping. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2010, 4, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.J.; Heimberg, R.G.; Frost, R.O.; Makris, G.S.; Juster, H.R.; Leung, A.W. Relationship of perfectionism to affect, expectations, attributions and performance in the classroom. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1999, 18, 98–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstadter, A. Emotion regulation and anxiety disorders. J. Anxiety Disord. 2008, 22, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay-Jones, A.L. The relevance of self-compassion as an intervention target in mood and anxiety disorders: A narrative review based on an emotion regulation framework. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 21, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.; Yap, K.; Scott, N.; Einstein, D.A.; Ciarrochi, J. Self-compassion moderates the perfectionism and depression link in both adolescence and adulthood. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langford, C.P.H.; Bowsher, J.; Maloney, J.P.; Lillis, P.P. Social support: A conceptual analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 1997, 25, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard, R.J. Support Systems and Community Mental Health: Lectures on Concept Development. Contemp. Sociol. 1976, 5, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaleri, M.A.; Olin, S.S.; Kim, A.; Hoagwood, K.E.; Burns, B.J. Family support in prevention programs for children at risk for emotional/behavioral problems. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 14, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osorio, A.E.; Settles, A.; Shen, T. Does family support matter? The influence of support factors on entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions of college students. Acad. Entrep. J. 2017, 23, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, C.O.; Thomson Ross, L.; Wills, N. Family factors and depressive symptoms among college students: Understanding the role of self-compassion. J. Am. Coll. Health 2020, 68, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiPrima, A.J.; Ashby, J.S.; Gnilka, P.B.; Noble, C.L. Family relationships and perfectionism in middle-school students. Psychol. Sch. 2011, 48, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, P.D.P. Factor structure and longitudinal measurement invariance of the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale-Brief on a Filipino sample. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 10, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Fang, Z.; Hou, G.; Han, M.; Xu, X.; Dong, J.; Zheng, J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, F.; Pommier, E.; Neff, K.D.; Van Gucht, D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2011, 18, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Personal. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, G.R.; Mueller, R.O.; Stapleton, L.M. The Reviewer’s Guide to Quantitative Methods in the Social Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Damodar, N. Basic Econometrics: Student Solutions Manual for Use with Basic Econometrics, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2014; Available online: https://files.pearsoned.de/inf/ext/9781292035116 (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Etkin, A. Functional neuroanatomy of anxiety: A neural circuit perspective. Behav. Neurobiol. Anxiety Its Treat. 2010, 2, 251–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, A.; DiBartolo, P.M. Anxiety and perfectionism: Relationships, mechanisms, and conditions. Perfect. Health Well-Being 2016, 177–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, G.L.; Hewitt, P.L.; Blankstein, K.R.; Mosher, S.W. Perfectionism, self-actualization, and personal adjustment. J. Soc. Behav. Pers. 1991, 6, 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Limburg, K.; Watson, H.J.; Hagger, M.S.; Egan, S.J. The relationship between perfectionism and psychopathology: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 73, 1301–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D.J. A meta-analysis of perfectionism and academic achievement. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 31, 967–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, K.H.; Jazaieri, H.; Goldin, P.R.; Ziv, M.; Heimberg, R.G.; Gross, J.J. Self-compassion and social anxiety disorder. Anxiety Stress. Coping 2012, 25, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dundas, I.; Binder, P.E.; Hansen, T.G.; Stige, S.H. Does a short self-compassion intervention for students increase healthy self-regulation? A randomized control trial. Scand. J. Psychol. 2017, 58, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.H. The stigma of mental illness in Asian cultures. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 1997, 31, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loya, F.; Reddy, R.; Hinshaw, S.P. Mental illness stigma as a mediator of differences in Caucasian and South Asian college students’ attitudes toward psychological counseling. J. Couns. Psychol. 2010, 57, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D. Self-compassion, self-esteem, and well-being. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2011, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehr, K.E.; Adams, A.C. Self-compassion as a mediator of maladaptive perfectionism and depressive symptoms in college students. J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 2016, 30, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.W.; Row, K.A.; Wuensch, K.L.; Godley, K.R. The role of self-compassion in physical and psychological well-being. J. Psychol. 2013, 147, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollister-Wagner, G.H.; Foshee, V.A.; Jackson, C. Adolescent aggression: Models of resiliency. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 31, 445–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.B.; Solberg, V.S. Role of self-efficacy, stress, social integration, and family support in Latino college student persistence and health. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 59, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, F.A.; Leonard, L.J. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and student academic success. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2011, 6, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germer, C.K.; Neff, K.D. Self-compassion in clinical practice. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 69, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.82 | 0.39 | 1 | |||||

| 2. Hukou | 1.45 | 0.50 | 0.08 * | 1 | ||||

| 3. Maladaptive perfectionism | 20.85 | 5.40 | −0.04 | −0.02 | 1 | |||

| 4. Anxiety | 11.75 | 4.46 | −0.02 | −0.08 * | 0.46 ** | 1 | ||

| 5. Self-compassion | 41.00 | 6.76 | 0.02 | 0.07 * | −0.38 ** | −0.44 ** | 1 | |

| 6. Family support | 20.76 | 4.89 | 0.09 | 0.07 * | −0.12 ** | −0.17 ** | 0.45 ** | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiong, Z.; Liu, C.; Song, M.; Ma, X. The Relationship between Maladaptive Perfectionism and Anxiety in First-Year Undergraduate Students: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 628. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080628

Xiong Z, Liu C, Song M, Ma X. The Relationship between Maladaptive Perfectionism and Anxiety in First-Year Undergraduate Students: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(8):628. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080628

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiong, Zhiheng, Chunying Liu, Meila Song, and Xiangzhen Ma. 2024. "The Relationship between Maladaptive Perfectionism and Anxiety in First-Year Undergraduate Students: A Moderated Mediation Model" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 8: 628. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080628